In part one of a three-part article, Hank Beecher aims to complicate the narratives set out by the electoral left that deny the possibility of revolution.

This piece is the first in a series that seeks to orient us on the most effective path to socialism. The question of how socialists should relate to elections, the state, and policy reforms has been a contested question for as long as the left has existed in the United States. A common framing of the debate presents two alternatives: to strive for policy reforms that usher in socialism piecemeal, or to build power outside of the state in preparation for a revolutionary break with capitalism. The former approach is often called electoralism. The latter, consisting of building up independent working-class power outside the state, is often framed as dual power. Electoralists and dual power advocates agree that we should learn from the past, but also that our strategy should be based upon current, 21st-century conditions. However, to the extent that the polemicists make claims concerning our contemporary situation, most rely on assumptions that feel intuitive but lack empirical justification.

If we are serious about developing an effective blueprint for social transformation, we must take stock of this moment in history. How do electoralist assumptions about our material conditions hold up to reality? For the most part, they don’t. The electoralist picture of our current moment lacks depth, nuance, and at times is simply wrong. Before exploring the faults in this picture, however, we must clarify the strategies at stake and the terms of the debate.

The Strategies

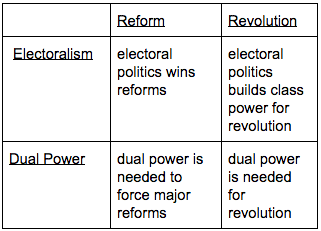

Generally speaking, electoralism on the left embraces the existing state as a plausible vehicle for socialist transformation. However, even some reform-oriented leftists do advocate for revolution; they just find that engaging in electoral politics is the best way to build the class power and political legitimacy socialists need to get there. Furthermore, others maintain that even winning major reforms requires building power outside the state to force the government to act on behalf of the working class. Thus the matrix of the reform/revolution and dual power/electoralism looks something like this:

Many, perhaps most, leftists maintain that we must engage in elections and build power outside of the state, but debate which of these should command the greatest share of the left’s resources. However, public engagement and resource-allocation on the left is still overwhelmingly electoral, and this trend shows no sign of changing. Thus the purpose of such electoral arguments is unclear if not to dissuade other socialists from occupying their time building dual power.

Examples of leftist electoral politics abound. Perhaps most prominent is DSA’s national campaigns for Bernie Sanders as President and Medicare for All as policy. Other examples include Justice Democrats politicians such Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, who have shifted the national dialogue to the left on the important issues of Palestinian liberation and US foreign policy. Additionally, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has been integral in mainstreaming the idea of the Green New Deal, a massive policy reform targeting climate change. These examples show how electoral engagement can help legitimize leftist ideas.

What actually counts as dual power isn’t always clear. Ambiguities infect common usage. Lenin articulated three qualities that define dual power: (1) the source of the power is the direct initiative of the people from below, rather than some initiative by the state; (2) the disarming of military and police and direct arming of the people; and (3) the replacement of state officialdom with organs of direct popular power or radically accountable, recallable officials without any elite privileges. Few, if any, contemporary dual power endeavors encompass all three of these. Sophia Burns differentiates between two types of dual power. The first type is alternative institutions that seek to replace state governance or the capitalist mode of production in a given space (think community gardens replacing commodity food production on a small scale). The second are counter institutions that actively engage in class-confrontation with capitalists or the state (think a militant labor union fighting the boss).

A further ambiguity is whether dual power must challenge both capitalism and the state; one institution might challenge state hegemony over a space, but not the mode of production in that space or vice versa. In his book Workers and Capital, Mario Tronti insists that the only concept of dual power that has any meaning is the power of workers within the labor process of commodity production itself, within the structured social relations of the factory. This understanding of class power is unapologetically reductionist. On the other hand, the Libertarian Socialist Caucus (LSC) in DSA explicitly rejects such workerist conceptions of class power, considering dual power to be a “strategy that builds liberated spaces and creates institutions grounded in direct democracy” to grow the new world “in the shell of the old.” This strategy is emergent, meaning dual power institutions embody the social relations with which we seek to replace capitalism, prefiguring a new society locally before and scaling up for an inevitable confrontation with the capitalist state.

For our purposes we will conceive of dual power as institutions outside the state in which the working class itself is empowered to act collectively, on its own behalf, to effect social transformation. Political independence from the capitalist class and its agents in government is non-negotiable. Rather than state representatives, legal advocates, or administrative bureaucracies, dual power congeals the workers into agents of their own liberation. “Workers” here is not to be understood in the narrow sense of those engaged in wage labor at the point of production, but as referring to all of those dispossessed by capital and left with nothing but their own labor power (and often not even that). This description suffices even if it doesn’t dispel all uncertainties associated with the term.

Examples of building dual power include efforts to organize tenant unions. Such unions fight displacement and improve living standards through mutual aid and collective action against abusive land owners. Organizations such as Los Angeles Tenants Union, Portland Tenants United, and the Philly Socialists organize tenants to build collective power against landlords and developers. These organizers have revitalized the rent strike, unleashing waves of mass struggle for control of the neighborhood. They have won major concessions from the ruling class and immediately improved the material wellbeing of many propertyless residents throughout the country.

Other leftists oriented by the dual power approach have gotten jobs at key companies with the intent of agitating and organizing workers for power in the workplace. Called “salting”, this strategy harkens back to the radical days when communist organizers built the CIO, when the labor movement was at its height. These efforts are beginning to bear fruit, with committees of workers at Target stores and major e-commerce warehouses leading wildcat walkouts and marches on the boss to win immediate material gains and inspire similar efforts across the country.

Few, if any, polemicists advocate for abandoning class struggle outside the realm of electoral politics. Indeed, most assert the need for grassroots pressure from below, using mass mobilizations to hold elected officials accountable. It’s unclear whether this qualifies as dual power and, if so, where the electoral beef is with leftists who feel compelled to spend their efforts organizing tenant unions or salting unorganized workplaces. Perhaps we could make use of Jane McAlevey here, who distinguishes between mobilizing and organizing.

Mobilizing refers to the model adopted by progressive social movements that depend on turning activists out in large numbers to protests. The goal is to pressure those in power to act on behalf of the working class. The more bodies at the rally, the better. Organizing, on the other hand, refers to the process of consolidating and solidifying relationships in the workplace and community, and strengthening bonds of solidarity. The goal is to empower the working class to challenge the power of capital through institutions of its own making. Mobilizing leaves current power structures intact but pressures the officialdom to represent working-class interests. Only organizing changes the underlying power dynamics animating society. Dual power, then, requires organizing institutions that challenge capitalist hegemony, not simply mobilizing an activist base.

By the characterization above, it’s hard to see what electoralists would oppose in the quest for dual power. One might be tempted to suppose that electoralists promote a mobilizing model of holding elected officials accountable through mass protests, activist culture, and the like. If this is not the case, it remains unclear what the actual disagreements are if not just a question of priority. What should the left spend its precious person-power and resources on? Electoral campaigns or building dual power? Unfortunately, the electoralist strategy rests on a faulty set of assumptions concerning the historic moment in which we operate.

The Electoralist Picture

While the dual power camp often invokes the Bolshevik Revolution as an example of the successful build-up and exercise of dual power, the electoral camp contends that our moment in history differs from that of the 1917 Russian Empire in important ways. First, in our current liberal democracy, elections are the way most people engage in politics and thus have the greatest legitimacy in the eyes of the masses. Insurrectionary politics only serve to isolate the left from the broader working class. We can call this the legitimacy argument since it proceeds from an assumption of electoral legitimacy. Secondly, unlike Imperial Russia, which was wracked by prolonged and disastrous engagement in World War 1, famine, and mass conscription, the United States is not embroiled in crisis on a scale that would shake the pillars of society and throw the whole system into doubt. We can call this the crisis argument because it proceeds from the presumed stability of our political-economic system, from the assumption that no significant crisis is on the horizon. Finally, electoralists argue that in modern democratic states, military might is too developed to be viably confronted. We can call this the firepower argument. But how does each of these claims hold up against the current state of affairs?

Legitimacy

As the default mode of civic engagement in much of the world, electoral politics seems obviously legitimate. However, on closer scrutiny this assumption falters. Not only does many of the working class people distrust electoral politics; they also view other, more militant forms of political agency as highly legitimate.

On a basic level, much of the working class is barred from participating in electoral politics, especially those with the most to gain from the overthrow of capitalism. For instance, those who would most benefit from criminal justice reform are barred from voting by felony conviction. Those terrorized by US foreign policy and border enforcement are excluded by citizenship requirements. The youth whose future is imperiled by the climate crisis are excluded on account of their age. But even amongst those who are eligible to participate in elections, most do not.

Of course, there are many reasons to abstain from voting that have nothing to do with whether one views it as legitimate. Apathy comes to mind. Many people may simply be content with the status quo. However, polls show that many American voters simply don’t trust our elections. For instance, 57% of non-white voters and half of women believe elections are unfair. These sentiments fluctuate and appear to reflect frustrations with the current party in power and displeasure with the latest election results. There’s a tendency for people to think elections are unfair when their party loses. This situation shows that for many people, loyalty to party outweighs loyalty to democracy. If perceptions of fairness can be taken as a measurement of legitimacy, then such findings undermine the assumption that the working class views electoral politics as legitimate. Indeed, most do not.

Elections aside, other forms of politics are viewed as highly legitimate by most Americans. Consider Red for Ed. Educators across the country have revived the labor movement by waging enormously successful, militant (and often illegal) wildcat strikes. It is hard to find a better example of mass, dual power politics in the United States. In repeated surveys, polls find that public support for the teacher strikes remains consistently high. Indeed, two-thirds of Americans support the strikes. Accordingly, more Americans support mass teacher strikes than consider our elections to be fair.

The legitimacy of militant collective action goes beyond support for strikes. Consider gun ownership. Roughly 40% of American adults own guns, about the same number as vote each presidential election cycle. Of those that own guns, 74% say the right to do so is essential to their freedom. Even among those who do not own guns, 35% agree on the importance of firearms to freedom. Thus the share of US adults with this view of gun ownership is higher than the share of US adults who participate in any given election. The right to bear arms is widely (though mistakenly) considered to have been meant as a hedge against tyrannical governments. Indeed, protection from tyranny is brought up time and again as a primary argument in favor of gun ownership, and not just on the right end of the political spectrum.

There is no doubt that the delineation of the right to bear arms in the United States is deeply infected with white supremacist motivations. However, the permanence of this feature of American identity, especially among rural communities, shows how for huge swaths of the working-class living in the United States, armed defense (and even insurrection) against tyranny is a profoundly legitimate right. Indeed, guns are just as widely viewed as a safeguard against tyranny as are elections.

To some degree, the argument from legitimacy is a red herring. Legitimacy is a shifting landscape. Take the Civil Rights movement. Today, the Civil Rights Movement is overwhelmingly viewed as legitimate. Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, the bus boycotts, sit-ins, Selma, and the March on Washington all occupy a special place in the pantheon of 20th Century US politics. In its day, however, most Americans opposed it. If public perceptions of legitimacy were its guiding principle, the movement likely would have never gotten off the ground.

Jane McAlevey traces the efficacy of the Civil Rights movement to deep organizing by unions and churches. Both institutions were essential in uniting the black working class of the South into a movement capable of changing the status quo. Importantly, as Joseph Luders shows, the success of the Civil Rights movement hinged on its power to disrupt the ability of Southern capitalists to turn a profit. When the costs of disruption outweighed the costs of conceding to the movement, the movement won. In other words, it was not the legitimacy of the civil rights movement that swept away de jure segregation. It was the ability of a deeply-organized Black working class to disrupt the ability of the South to function as an engine of capital accumulation. Only decades later is the movement widely viewed as legitimate.

Legitimacy is an important consideration for leftists. However, it is part of the task of leftists to shift the terrain of public perception of what constitutes legitimate forms of political agency and what formations are legitimate mantles of political power. The task is two-fold: to delegitimize the bourgeois state and to legitimize new formations of working-class power. To prioritize electoral politics over building a base of working-class power outside the state achieves the opposite. Instead, we must expand notions of political agency by showing that the workplace, the neighborhood, and the home are all political spaces and our power lies in our solidarity.

Crisis

The crisis argument is perhaps the most curious aspect of the electoral camp’s case against dual power. Polemicists on both sides of the debate seem unclear about what actually constitutes a revolutionary crisis. It is not merely a crisis in the perceived legitimacy of the ruling class. György Lukács, succinctly invoking Lenin, explains a revolutionary crisis thus:

[T]he actuality of the revolution also means that the fermentation of society – the collapse of the old framework – far from being limited to the proletariat, involves all classes. Did not Lenin, after all, say that the true indication of a revolutionary situation is ‘when “the lower classes” do not want the old way, and when “the upper classes” cannot carry on in the old way’? ‘The revolution is impossible without a complete national crisis (affecting both exploited and exploiters).’ The deeper the crisis, the better the prospects for the revolution.

Thus, while crisis certainly involves a subjective component, we are not concerned with a mere crisis of legitimacy. Crisis arises from the inability of the system to reproduce its status quo, not just for the working class, but also for the ruling elites. Such a crisis is already underway. If we strive to be empirical and adapt our strategy to the actual, material conditions of our particular moment in history, then we simply cannot dismiss the magnitude of climate change and global ecological crisis we face. It may be impossible to predict how society will respond to the looming crisis, but one fact is certain: a crisis unprecedented in magnitude and scope is absolutely on the horizon and advanced capitalist states have thus far, almost without exception, proven wholly unable to do anything to prevent or mitigate it. It poses a dire and unavoidable threat to the very way the economy functions and to countless processes of capital accumulation. To deny this claim one must be as hostile toward a scientific worldview as an obtuse politician throwing snowballs on the floors of Congress.

The consensus among relevant experts is approaching 100%. The conditions that have supported human civilization since its dawn have frayed and a future of business-as-usual is emphatically impossible. The cause is fundamental to the way our economic system functions. None of these are fringe leftist views. Among scientists and experts of all stripes, those that reject this prognosis now form a vanishingly small superminority.

No leftist outright denies the climate crisis. Most acknowledge it as proof of capitalism’s inherent unsustainability and identify it as one of the major problems for socialists to solve once taking power. Indeed, this is why DSA resolved to throw its weight behind the Green New Deal. This broad recognition of climate crisis as an issue, however, strangely does not lead to a recognition of crisis as a material condition that should dictate strategy. Crisis is the defining feature of our future. To deny this abandons our commitment to materialism. Failing to place this fact at the very center of our politics not only brings an incomplete picture of our conditions into political strategy; it fully redacts the present moment from our analysis.

Climate change acts as a catalyst for latent social contradictions. It exacerbated class conflict and oppression in countless ways. Consider the illegal southern US border, which was drawn by conquest and has long fractured indigenous communities in the region. The authoritarian nature of white nationalism exists regardless of climate change, but the magnitude of its violence has wildly escalated as climate change uproots the rural working class in Central America, only to have them ripped from their loved ones and locked indefinitely in concentration camps at the border. Consider Puerto Rico, where climate-intensified hurricanes have wreaked havoc on the island, killing nearly 3,000 residents in 2017 and accelerating colonial oppression and plunder. Consider the tribal nations in the Pacific Northwest, who are being dispossessed of their remaining national territories as rising seas swallow their land. Climate crisis is class conflict on steroids and for much of the working class, eco-apartheid already exists.

Climate change blasts open new fronts for class struggle. The new normal for hurricane season stands out. The inundation of major built environments such as New Orleans, the Rockaways, and Houston were unprecedented for much of US history and sparked desperate battles for the right to the city. On the one hand, the storms unleashed new waves of capital accumulation in the form of shock-induced gentrification. Capitalists sought to leverage the destruction to privatize entire cities. On the other hand, communities organized for mutual aid and to fight off developers who circled the carnage like vultures. There are opposing paths of exit from every crisis.

Climate crisis is already a crucial driver of class struggle. To deny this excludes vast portions of the working class from our analysis. In such a chauvinist view, the working class only encompasses citizens enjoying enough national or racial privilege to be sheltered from the immense suffering already unleashed by an unraveling climate. Not only is crisis emphatically immanent, but vast portions of the most oppressed sections of the working class are already embroiled in it.

Firepower

The firepower argument is the most compelling line of reasoning from electoralists. In this view, modern capitalist states differ from those that have been toppled by dual power insurgency in at least three important ways. First, technologically-advanced modern militaries, particularly that of the US, are far more powerful than any other military in history. The logic of building dual power points ultimately to a confrontation with such forces, which no rabble of leftists could ever hope to win.

Second, in successful past rebellions, revolutionaries have relied immensely on factions of the military turning against the state and joining the revolution. Indeed, these mutinous factions were a central aspect of dual power in the Russian Revolution. Defection was widespread because most enlisted soldiers were not in the military voluntarily; they were conscripted to fight for empire in World War I. Vast portions of the military were loyal to the Russian masses and working class from which they were conscripted. Indeed, many soldiers were Bolsheviks before they were drafted into the imperial war. These soldiers were crucial for organizing mutinies to turn the military against the state. Electoralists argue that the current situation could not be more different. The US eliminated conscription decades ago. Defection within the ranks is therefore highly unlikely; it seems safe to assume that most of today’s forces are loyal to the government they voluntarily serve.

Third, there is a robust right-wing militia movement in the US that effectively serves as an extension of the most reactionary aspects of state power. Not only do leftists have to contend with the formal military; they must contend with these paramilitary forces.

Though a compelling advisory against insurrection in the immediate future, this argument is not an airtight case against prioritizing dual power. The reasons are three-fold.

Diversity of Dual Power

First, there are important ways of building dual power that don’t entail armed insurrection. Power takes multiple forms, and firepower is only one of them. Control over production and social reproduction is another. For instance, building the social infrastructure to wage a mass strike is every bit as much a project of dual power as assembling an insurrectionary force. Additionally, while modern technology has exponentially enhanced the might of the military, it has magnified the power of certain sectors of the working class as well. Military power is produced and reproduced by labor. Skilled workers employed by companies such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) yield more structural power than perhaps any other collection of people ever.

Consider the following: a mere two thousand AWS workers develop and maintain the tech infrastructure responsible for hosting over half of the internet. That content encompasses the Pentagon’s cyberinfrastructure. It also includes the online presence for countless businesses, some of the biggest oil and gas companies, entire nations, court systems, and stock markets. The share of the web-hosted by AWS is so great that there isn’t enough space on backup servers to absorb it all. Furthermore, Amazon tech workers develop and maintain an exploding share of global logistics networks, a sector crucial to transnational chains of capital valorization. There has never been a more concentrated bottleneck in global capital accumulation, nor one in which the skilled workers are more difficult to replace. Just as tech has empowered imperial militaries to unprecedented heights, so too has it endowed labor with might unknown to the revolutionaries of the past.

It’s true that the capitalist state may marshal its military to crush the prospect of a successful seizure of power through a mass strike. Indeed, there is precedent for the White House declaring certain industries essential to national security and sending in the troops to prevent work stoppages. However, such a reaction is also in the cards for an electoral rupture with capitalism. If military confrontation is the logical endpoint of dual power, then it’s also the logical endpoint of an electoral road to socialism. The electoralist may argue that at least in the electoral process, socialists establish legitimacy and thus the masses will rush to the defense of socialism as a defense of democracy. However, we have already established that, for instance, strikes are viewed as at least as legitimate as elections. Why, then, would the masses rush to the defense of a party that takes power through electoral means but not one that seizes power by successfully executing a mass strike? Thus the prospect of military reaction provides no reason to prioritize elections over dual power. Indeed, it provides reason to prioritize the latter.

Military Cohesiveness and Troop Loyalties

The electoral account over-assumes the degree to which military members are a monolithic, volunteer force dedicated to the cause of empire. Studies suggest that the primary motivation for most members to enlist is economic. Having the government pay for college tops the list. This phenomenon is often called an economic draft or economic conscription since many members join because they lack better prospects for financial security or social advancement. If most members also like being in the military or are committed to their work, the electoral argument would be stronger. However, this is not the case.

Once a recruit enlists, there is no turning back. A typical term of service for enlisted members is six years. Once enlisted, a servicemember cannot quit before that time is up. Members have the opportunity to renew at the end of their initial term, but few do. In 2011 the average length of service by enlisted members of the military was 6.7 years, only a few months longer than the typical minimum troops are typically required to serve. Given the attractive benefits and ability to retire young, why wouldn’t more troops choose to make a career in the military? As it turns out, most want out. In 2015, half of US troops reported feeling unhappy and pessimistic about their job. Nearly half also reported not feeling committed to or satisfied with their work. In light of these sentiments, our “volunteer force” turns out to be largely made up of folks who are in for the future economic benefits and would likely quit if they could. Furthermore, these high turnover rates mean hundreds of thousands of troops re-enter civil society every year, oftentimes struggling to adjust and feeling abandoned by the government they served. These dynamics suggest that we should view the high turnover as a routine, de facto mass defection of troops.

Turning to the dynamics of loyalty within the US military, consider the following trends: 1) the membership of the US military is becoming increasingly politically polarized, to such a degree that many commentators are beginning to wonder if this polarization is a problem. 2) The military itself is becoming increasingly politicized with President Trump and the Republicans trying to paint themselves as the party of the armed forces. Consider what the latter point means for the hundreds of thousands of service members who do not align with the party of Trump. If the trend of polarization and politicization continues, then we can expect to see cracks widen in the cohesiveness of the membership’s alignments. The political identifications of specific groups within the military tend to reflect the politics of the broader communities from which they hail. Like in conscript armies, members of the US armed forces have affinities with their social groupings outside the military. Accordingly, in place of the electoralist image of the military as a monolithic volunteer force with unfaltering allegiance to empire, the reality is a mass of politically diverse and increasingly polarized service members, half of whom don’t actually want to be in the military and expressly lack commitment to the job.

Civilian Firepower

In terms of firepower, the US differs from many other societies, past and present, in another important way. While it has a military of unprecedented strength, its masses are also uniquely well-armed. Consider the following trends. Even among minorities and oppressed groups, gun ownership is common. One in three Black American households have guns, as do one in five Hispanic households. A quarter of non-white men are armed. Twenty-two percent of women personally own a firearm. While it’s true that Republicans are the most likely to own guns, Independents are nearly as likely and make up a much larger share of the population. Millions of Democrats and self-identified liberals also bear arms.

No doubt, there are disparities in the contours of gun ownership that we can’t ignore. The balance of firepower between white men and the rest of society certainly skews in favor of the former, and guns are relatively concentrated in the hands of political conservatives. Equally troubling, those making over $100,000 a year are almost twice as likely to own a gun as those making under $25,000 a year. However, rates of gun ownership are roughly similar at all income levels over $25,000. This fact indicates that, while the poorest Americans are the least likely to own guns, above a relatively low-income threshold, class is not a strong determinant in gun ownership. Thus, while many gun owners have a vested interest in the preservation of both capitalism and white supremacy, many do not.

Much of the dynamics of gun ownership may reflect that rural America is both a conservative stronghold and where most gun owners reside. Changing the first of these factors, the political orientation of the rural working class, is a crucial task of the left regardless of considerations about firepower. The American countryside used to be a hotbed of left-wing militancy. Any ambitious socialist movement has the responsibility to make it so again. The alternative is to abandon the masses outside of coastal metropolises. Leftists must win over the working class wherever they reside, and the working class in much of the US is already well-armed. Thus the process of winning the masses to socialism outside of urban activist strongholds would itself help neutralize the imbalance in firepower.

One of the more troubling aspects of civilian gun ownership is the far-right militia movement. In recent years, civilian militias have emerged victorious from standoffs against the government. While much of the movement does oppose state power, it is composed of some of the most reactionary elements acting in defense of capital, unrestricted private property rights, and racial privilege. However, far from showing some immutable quality of working class gun owners, the militia movement shows how armed civilians are capable of organizing to oppose the state.

A striking example took place in 2014, when civilian militias amassed to face down federal, state, and county agents in southern Nevada. Rancher Cliven Bundy owed (and still owes) millions of dollars to the federal government. For decades, he has been grazing his cattle on federal lands while withholding grazing fees. After legal prosecution failed to compel him to pay, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) sent officials to round up and remove his cattle from federal range. In response, Bundy called on the militias. At least five paramilitaries assembled to back his personal claim to federal land in a face-off with government agents. In multiple press releases, Bundy expressed his refusal to accept the legitimacy of the federal government. In the end, the government forces backed down and cancelled its round-up, leaving Bundy to forcefully enclose public lands for his own commercial use. Five years later, he continues to use federal range as his own commercial asset and has not paid a dime. The militia movement successfully challenged the federal government and established sovereignty over a small chunk of the Southwest desert.

The dynamics at play in the standoff share many similarities to a situation of dual power. Two opposing forces claimed legitimacy and sovereignty over a piece of territory. The militia movement can thus be seen as effectively building a “state within a state,” albeit a capitalist, proto-fascist state. No doubt, the federal government would not treat a socialist threat so kindly.

The foregoing account shows that a vast build-up of civilian firepower already exists. Its most organized and disciplined formations have challenged the state and come out victorious on more than one occasion. Unfortunately, much of this movement should be considered a paramilitary extension of bourgeois power that supplements, not counters, the formal military. Most right-wing militias are characterized by jingoism and commitment to empire to a degree that many enlisted service members are not. However, even this account deserves nuance.

The militia movement itself has experienced defections and splits over the inclusion of racist ideologies in the movement. Much of it explicitly opposes racism and antisemitism. The overtly racist factions of the movement typically have to emphasize their anti-government sentiments and hide their racist elements in order to attract followers. Indeed, in today’s movement, the underlying ideological unity is anti-government more so than white nationalist. Much of the movement views itself as opposing state oppression. In fact, in the standoff in Nevada, it was a video of federal agents body slamming a woman in the Bundy family that brought so many members to the fight.

More importantly, the right-wing militia movement is only a very small fraction of the armed and trained citizenry. It has been able to grow in part by positioning itself as a conduit for disaffected veterans. There’s no reason the left can’t begin to do the same and grow an alternative pole of attraction for the hundred of thousands of service members leaving the military each year. This strategy, however, is incomplete. In addition to disarming reactionary and bourgeois elements in society, any strategy regarding firearms within the US must also prioritize the self-defense of the oppressed and internally colonized. In small ways, this is already occurring. We will return to this point in a later piece.

These considerations do not open up the possibility of armed insurrection against the government any time in the immediate future, but they do complicate the electoralist picture. First, some of the most promising and important types of dual power will come from organizing workers at the points of production and reproduction, not from simply picking up guns. Just as the military has been empowered by modern innovation, so have the workers who produce and maintain that technology. Secondly, the military is likely not a homogenous political force that would slaughter fellow Americans engaged in something like a mass strike. Indeed, we see increasing political polarization within the ranks and mass de facto defection every year. Third, much of the US working class is already armed and socialists are already charged with the task of winning them over.

Conclusion

The electoralist picture obscures a great deal of nuance in the social, political, and historic landscape of the United States. It does so in ways that fundamentally undermine its case against dual power. First, it overstates the legitimacy in the bourgeois state and the parliamentary process in relation to other forms of political agency. It also mistakes the role legitimacy has historically played as an engine of social transformation.

Secondly, and most curiously, it fails to acknowledge the climate crisis as a crucial feature of the current moment. While leftists in general conceive of climate change as an issue, deep crisis defines the very real material conditions that should determine strategy. A left exit from this crisis thus must be a crucial framework for how we move forward.

Finally, the dynamics of firepower indeed place great constraints on how we can effectively build dual power. They do not, however, foreclose the possibility. In the next part of this series, I will explore several examples of contemporary attempts to address crisis electorally, why these attempts have failed or succeeded, and how they should inform our approach to socialist transformation moving forward.