Cliff Connolly critiques CounterPower’s vision of the “party of autonomy” and offers an alternative vision of the mass party.

The US left is at a critical juncture where the structure and focus of our organizations will soon be decided. On the one hand, we positively have ongoing processes of cohesion in play with DSA chapters collaborating on writing a national platform and far-flung sects coming together under the banner of Marxist Center. On the other hand, we have many comrades across ideological lines who still echo opposition to the idea of a tightly structured national organization. Central to this contradiction is the question of the party: should socialists strive to build an independent political party, and if so, what should that look like? CounterPower has put forth one possible answer in their article Create Two, Three, Many Parties of Autonomy! They are dedicated organizers and we should all be glad to have them in our midst. However, their strategy of eschewing the mass party model and encouraging the spontaneous formation of multiple “parties of autonomy”, and counting on these disparate groups to unite into an “area of the party”, is unworkable in the long term.

Their argument for the many parties strategy rests on a number of errors—historical misrepresentation (no, CPUSA was not a party of autonomy), uncritical acceptance of failed models (Autonomia Operaia gives us more negative lessons than positive ones), an over-reliance on spontaneity (movements have to be built intentionally), an aversion to leadership (no, it doesn’t automatically create unaccountable bureaucracy), and a confusion of terms (putting anarchist and Marxist vocab words together does not solve the contradictions between them). We will explore each of these points in greater detail. There is also an implicit assumption of false dichotomies built into the many parties line—either we build parties of autonomy or slip into sectarianism, either parties of autonomy or dogmatism, either parties of autonomy or top-down bureaucracy. There is a kernel of truth present here; we certainly don’t want a dictatorship of paid staffers. However, parties of autonomy are not a solution to this problem — in some ways, they would exacerbate the problem.

This was initially written in response to CounterPower’s original essay in 2019, but has since been amended to include dialogue with the updated version published in 2020. The differences between the two are significant and raise new concerns about the many parties model. The most interesting addition in the update concerns the role of cadre — highly trained organizers dedicated full-time to party activity. While we agree wholeheartedly on the necessity of these professional revolutionaries, there is a difference of emphasis that merits debate. This issue will be explored in greater detail below.

That CounterPower started this conversation on the party question is a gift to the whole of the US left—it must be addressed for our organizations to move forward. While many of us vehemently disagree with their conclusions, we should be grateful for their company. After examining each piece of their argument for the many parties model and taking note of its shortcomings, we will investigate a viable alternative—a mass party of organizers built on the principles of struggle, pluralism, and democratic discipline.

Historical Clarification

There are a number of historical errors throughout CounterPower’s article. By this we are not referring to a difference of opinion about a certain historical figure’s thought process or the motivations behind a particular decision, but rather factual inaccuracies. This in itself does not mean the thesis of the article is automatically false, but it does betray a dependency on unfounded assumptions. First, there is the assertion that the Russian soviets arose organically without being built by socialists, at which point the Bolsheviks joined them and worked harmoniously with other autonomous parties in this “area of the party” to link the soviets to other sites of struggle. Second, there is the quotation from Mao Zedong’s 1957 Hundred Flowers speech, which CounterPower uses to bolster their argument for parties of autonomy. Finally, we are led to believe that both the FAI and the Alabama chapter of the Communist Party USA are exemplars of the many parties model.

We will begin with the relationship between the Bolsheviks and the soviets. Here is CounterPower’s characterization:

“The organized interventions of a revolutionary party thus take place ‘in the middle,’ as mediations between the micropolitical and macropolitical. This has been a distinguishing feature of successful revolutionary parties, as in the example of the Russian Revolution of 1917, when clusters of Bolshevik party activists concentrated in workplaces, recognizing that the participatory councils (soviets) emerging from grassroots proletarian struggles embodied the nucleus of an alternative social system. Thus the party’s organization at the point of production enabled revolutionaries first to link workplace struggles against exploitation with the struggle against imperialism, and then to link the emergent councils with the insurrectionary struggle to establish a system of territorial counterpower”.

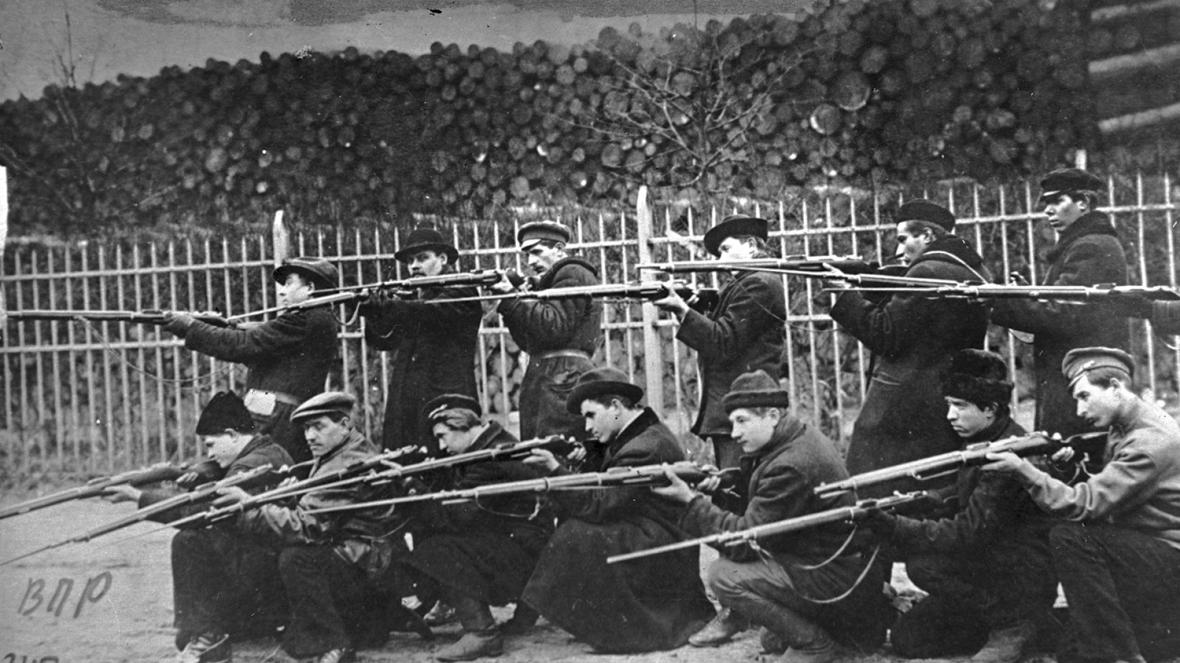

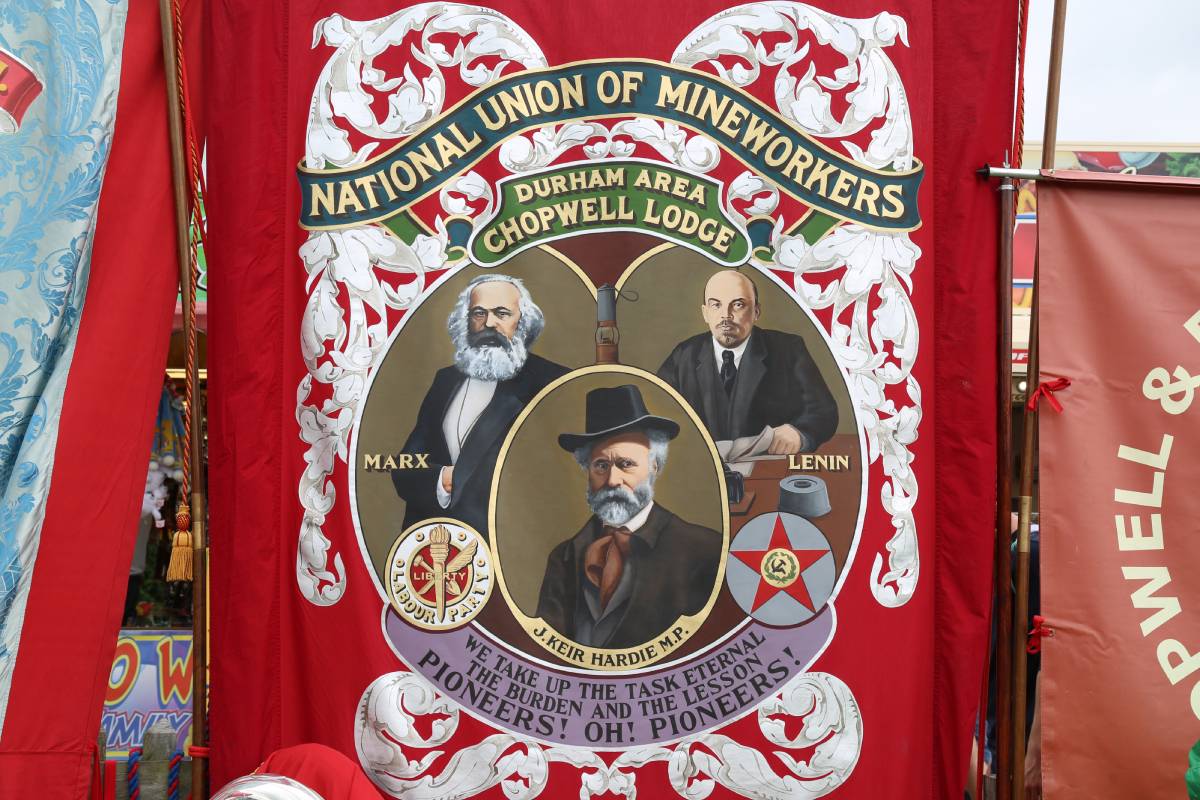

On the contrary, it is of utmost importance to recognize that the soviets, factory committees, and militias that formed the backbone of the Russian revolution were built intentionally by socialists. While different factions in the Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party eventually split into separate organizations as the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, both groups were instrumental in the creation of these mass organizations. They did not emerge organically from economic struggles with bosses and feudal landlords like some of the trade unions and peasant associations, but instead were the product of a socialist intervention in economic struggles which emphasized the need for political organization. This strategy, commonly referred to as the “merger formula”, was theorized by Marx and Engels, popularized by the German socialist party leader Karl Kautsky, and accepted by Russian socialists of all stripes (most notably Lenin).1

The Bolsheviks did not merely help workers build their fighting organizations. They also competed with political rivals for leadership in them. Beyond their efforts that we would call “base-building” today, the Bolsheviks also invested significant resources into propaganda efforts and electoral contests. The struggle for elected majorities in the soviets in 1917 was pursued in tandem with a strategy of running campaigns for municipal offices and the Constituent Assembly (the bourgeois parliament of the Provisional Government), and it worked. The Bolshevik candidates for the assembly were able to publicly oppose the policies of the Provisional Government, while the elected deputies in the soviets were able to win over the working class to the task of seizing political power. These electoral efforts were instrumental in establishing a democratic mandate for the October Revolution.2 Consider these words from leading Bolshevik (and later leading opposition member purged by Stalin) Alexander Shliapnikov, in 1920:

The Russian Communist Party (RKP), as the history of the preceding years indicates, is the only revolutionary party of the Working Class, leading class war and civil war in the name of Communism. The R.K.P. unifying the more conscious and decisive part of the Proletariat around the Revolutionary Communist Program of action and drawing to the Communist banner the more leading elements of the rural poor, must concentrate all higher leadership of communist construction and the general direction of policy of the country.

Clearly, the Bolsheviks did not consider themselves a “party of autonomy” working side by side with the Menshevik reformists in a broad “area of the party”. Nor did they simply fuse with organic economic struggles in the trade unions. The reality couldn’t be further from CounterPower’s insinuations: the Bolsheviks were a party of political organizers who started as a minority and slowly won over sections of the working class through diligent mass work and bitter struggle with the other parties of the day. By engaging in this process, they eventually took on a mass character and became capable of leading social revolution. The lesson to learn from the Bolsheviks is this: we must win political hegemony in whatever independent organs of proletarian power that we help build, using every available means, including running opposition candidates in bourgeois elections to expose broader sections of the class to our ideas.

Now we will consider Mao’s echoing of the old Chinese proverb “Let a hundred flowers blossom, let a hundred schools of thought contend.” This line of poetry is used by CounterPower to demonstrate the need for dozens of independent communist grouplets to form and collaborate on the task of social revolution. They attribute the quote to Mao, but is this how he used it? The short answer is no. It comes from a speech he gave in March 1957 at the Chinese Communist Party’s National Conference on Propaganda Work. It is true that he called for a hundred schools of thought to contend, but this was in the context of winning unaligned intellectuals over to the party’s socialist ideals. He gave a thoughtful and nuanced analysis of how the party could accept criticism from the broader population without sacrificing their legitimacy as the ruling organization of the country:

Ours is a great Party, a glorious Party, a correct Party. This must be affirmed as a fact. But we still have shortcomings, and this, too, must be affirmed as a fact…Will it undermine our Party’s prestige if we criticize our own subjectivism, bureaucracy and sectarianism? I think not. On the contrary, it will serve to enhance the Party’s prestige. This was borne out by the rectification movement during the anti-Japanese war. It enhanced the prestige of our Party, of our Party comrades and our veteran cadres, and it also enabled the new cadres to make great progress. Which of the two was afraid of criticism, the Communist Party or the Kuomintang? The Kuomintang. It prohibited criticism, but that did not save it from final defeat. The Communist Party does not fear criticism because we are Marxists, the truth is on our side, and the basic masses, the workers and peasants, are on our side.

Clearly, in March 1957 Mao was concerned with building a mass party, not opening space for a loose collaboration between multiple parties aimed at building socialism. Unfortunately, the Chinese Communist Party was underprepared for the criticism they would soon face and reversed the Hundred Flowers Campaign. By July of that same year, the Anti-Rightist Campaign brought a series of purges underway, which got so out of control that Mao had to restrain his subordinates from excess killing. Perhaps Chinese conditions in 1957 were different enough from American conditions in 2020 that this was acceptable, or perhaps Mao the statesman should not be looked to for inspiration as much as Mao the general or Mao the revolutionary. It is beyond the purview of this article to answer that question. What is certain CounterPower draws the wrong lesson out of Mao’s 1957 speech.

After quoting Mao, CounterPower moves on to claim that the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) is in practice a party of autonomy working within the “area of the party” of Spain’s National Confederation of Labour (CNT). Although the idea of “parties of autonomy” was not formulated until forty years after FAI’s founding, there may be a kernel of truth to this claim. For example, if FAI formed a loose coalition with CNT organizers and worked with them on shared projects, this argument could make sense. The reality, however, is that FAI is essentially a hard-line anarchist faction within CNT that has consistently fought for political hegemony within the broader organization and even purged ideological rivals like Ángel Pestaña. Perhaps they were right to do so; it is outside the scope of this article to pass judgment on the internal political conflicts of the CNT.

Despite CounterPower’s framing of the FAI as an independent anarcho-communist organization with an “organic link” to the CNT, they are an explicitly anarchist faction struggling to dominate the politics of the Spanish labor movement. They act as a pressure group within the confederation to make CNT adhere to what they perceive as purely anarchist theory and praxis without deviation. This is not a “symbiotic relationship”, it is realpolitik under a black flag. Roberto Bordiga’s window dressing cannot give us a clear understanding of Spanish labor politics; historians like José Peirats and Paul Preston would be better suited to aid this investigation.

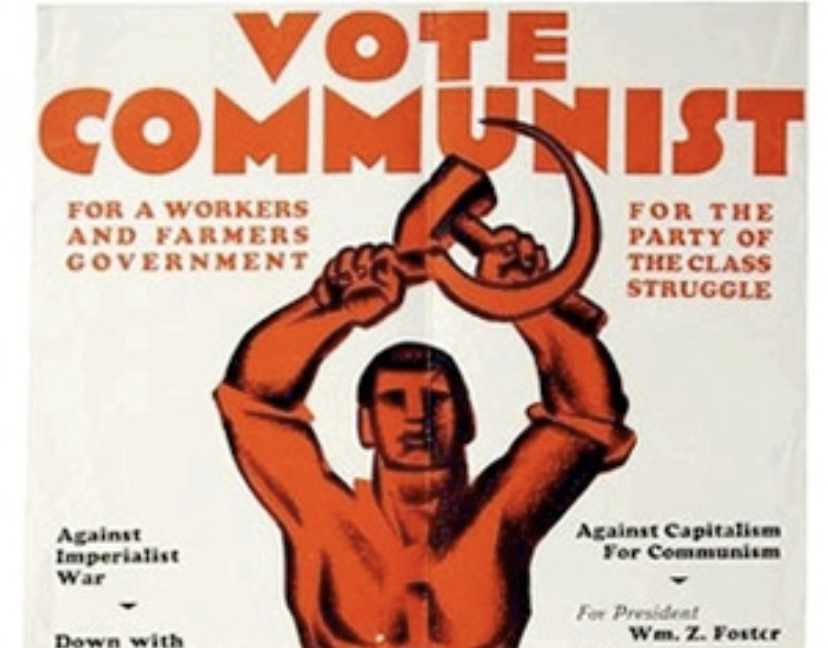

In the updated version of their essay, CounterPower cites the Alabama chapter of CPUSA as a historical example that serves to “elucidate the role and function of a party of autonomy”. This could not be further from the truth. Similar to the FAI, the party of autonomy model would not even be theorized until fifty years after the Alabama chapter’s founding. CPUSA was a mass party with local chapters all over the country for at least the first half of the twentieth century. The Alabama chapter in particular was the result of discussions on “the Negro question” at the Sixth World Congress of the Communist International, after which the Central Committee of CPUSA chose Birmingham as a headquarters for its foothold in the South.3 Its success in organizing rural and urban communities in the deep south of the 1920s is proof that the mass party model can be adapted to regional conditions and accountable to local rank and file members. Describing this centralized party model as a “party of autonomy” is categorically false.

Spontaneity vs. Base-Building

Now that the historical context of CounterPower’s narrative has been clarified, we should examine the contradiction between their ideological commitment to spontaneity theory on the one hand, and their practical commitment to base-building on the other. Does the working class organically form explicitly political fighting organizations, or is a socialist intervention required for this to occur? This is a never-ending debate between Marxists and anarchists, despite the pile of evidence pointing to the latter. Some would argue that this debate is pointless at the present moment, and these differences are best put aside until the workers’ movement has grown. We would reply: “First, comradely debate in no way hampers unity of action. We can continue base-building efforts while disagreeing on political questions, and it is only through debate that we might one day get on the same page. Second, simply by engaging in the act of base-building with us, you are agreeing with our point in practice while denying it in theory.” How is this possible?

Our comrades in CounterPower are the perfect example. They admit the masses will not come to accept communist ideas on their own:

From strike committees to workers’ councils, tenant unions to neighborhood assemblies, the disparate forms of organized autonomy that arise in the midst of a protracted revolutionary struggle will not automatically fuse with communist politics to create a cohesive system of counterpower.

Yet they don’t address where these councils and unions come from. The reader gets the sense that these organizations simply pop up during times of crisis, as workers get frustrated with bourgeois politics and independently come to the conclusion that they need to organize against their boss or landlord. This may be true in a minority of cases, but most proletarian fighting organizations come from the same source as the Russian soviets: dedicated socialist base-builders. Who built Amazonians United? Who built Autonomous Tenant Union Network? Who built UE, ILWU, and the original CIO? In every case, the answer is: workers and intellectuals who read Marx, became socialists, and decided to organize.

Our responsibilities go beyond just founding these mass organizations; we have to compete for hegemony within them as well. If we neglect this crucial aspect of organizing due to a fetishization of the autonomy of the masses, reformists and even reactionaries will gladly fill the gap. In the case of something like workers’ councils, we cannot have any illusions that they provide anything beyond a means of representation for political tendencies within the movement. This is precisely why the Bolsheviks competed so vigorously with the reformist Mensheviks and populist Social Revolutionaries for elected majorities in the soviets. In fact, the Bolsheviks only adopted their famous slogan “All Power to the Soviets” after they had secured elected majorities in them.4 We only need to look at the difference between the Soviet Republics established in Russia and the brutally crushed Soviet Republic of Bavaria to understand the limitations of the model. Without influence from committed revolutionaries, mass organizations can be rallied to the banner of class-collaboration (as the Russian soviets were before Bolshevik intervention) or adventurism (as in the case of Bavaria).5

CounterPower’s overestimation of proletarian spontaneity has practical consequences for its members. In his recent article In Defense of Revolution and the Insurrectionary Commune, Atlee McFellin analyzed the November 2020 election and drew parallels between it and the situation which produced the Paris Commune. Fearing that elections may never take place again, McFellin argued against any participation in electoral efforts (including, but not limited to the creation of a political party independent from the Democrats). What was proposed instead? “Self-defense forces, solidarity kitchens, and everything else that is required to repel fascist assaults”. In other words, anything but a class-independent party capable of coordinating the struggle for socialism across different political, economic, and social fronts. Rather than face the reality of the radical left’s current irrelevance in national politics and the labor movement, and chart a course to resolve this, comrade McFellin called for the construction of insurrectionary communes as a response to the consolidation of ruling class interests under Joe Biden. Whether the working class has the spontaneous energy necessary for this task remains to be seen; if it does, we would be ill-advised to hold our breath in anticipation but should wince at the inevitable brutal consequences if such adventurism bears fruit.

While in theory, CounterPower glosses over the role of communists in building workers’ organizations, in practice they are engaged in precisely this work. Rather than relying on the spontaneous initiative of the masses, they actively build tenant and labor unions, political education circles, and other necessary vehicles of class struggle. In fact, they do it remarkably well. This is what makes the claim that communists must “fuse with grassroots organizations” after they appear rather than actively building them in the first place so bizarre. Ultimately, our task as communists is to build mass organizations of class struggle, and then rally the most active participants within them to a mass communist party. By uniting in one party, we can direct the efforts of thousands of organizers according to a commonly agreed upon plan, which is an absolute necessity for the workers’ movement to grow.

The Role of Cadre

The discussion of cadre organizers is given new attention in CounterPower’s update to their original essay. It mostly focuses on the role these committed party members play in shaping revolutionary strategy and connecting it to active proletarian struggles. As seen in my Cosmonaut article Revolutionary Discipline and Sobriety, those of us who favor the mass party model are in complete agreement with CounterPower on the importance of cadre:

Any collective project, whether a revolutionary labor union or a church’s food pantry, will expect a higher degree of involvement from its core organizers than from its regular members. Not everyone has the time or the technical skills needed to bottom-line such endeavors, and those who do have a responsibility to step up to the plate. These small groups, or cadre, are the powerhouse of the class. Taking direction from the masses they live and labor with, cadre members should focus their lives on facilitating the self-emancipation of the proletariat.

CounterPower rightly points out that these dedicated full-timers are a prerequisite for the development of robust internal political education, external agitation, and consistent recruitment to mass work projects. Key to the every-day functioning of these cadre groups is the organizational center to which they are accountable (and preferably subject to democratic discipline by the whole membership of the organization). While the mass party shares the party of autonomy’s commitment to a common political platform and program, the main difference between the two models is one of scope. Whereas the “area of the party” is composed of diffuse autonomous organizations with separate and often contradictory programs, the local chapters of the mass party work together on a common, democratically agreed-upon plan. As the experience of the Alabama chapter of CPUSA shows, this does not mean the plan cannot be adapted to meet local concerns.

In fact, the mass party model historically proves more capable of achieving its aims than any other method of party organization, whether it is compared to the bourgeois fund-raising parties that dominate US politics or the Italian autonomist model revived by CounterPower. This will be elaborated below in our examination of the Autonomia Operaia movement. For now, suffice it to say that while we agree with our autonomist comrades on the importance of cadre, the mass party model is best suited to coordinate their efforts.

Precision of Terms

Further complicating the problems of CounterPower’s revolutionary strategy is an incoherent collection of opaque and often contradictory terms. Few throughout history have tried to synthesize the theories of the Bolsheviks, Rosa Luxemburg, Bordiga, and Malatesta, mostly because it makes no sense to do so. This blend of anarchist shibboleths (affinity groups, autonomy fetishism, Bookchin references) and communist vocabulary (party cadre, collective discipline, professional revolutionaries) is neither an oversight nor the product of genuine cross-ideological left unity. CounterPower is a Marxist organization with a niche ideology informed mainly by the experience of the Italian Autonomia Operaia movement. The fact that they mask this behind an appeal to every possible leftist tendency is frankly dishonest, and makes their writing difficult to follow. Since all these ideas have been presented to us as complementary and harmonious, we must investigate the contradictions between them in order to get a clearer picture.

First, we should consider their framing of the ideas of Luxemburg:

In contrast to a bourgeois party, Rosa Luxemburg identified that a revolutionary party of autonomy ‘is not a party that wants to rise to power over the mass of workers or through them.’ Rather, it ‘is only the most conscious, purposeful part of the proletariat, which points the entire broad mass of the working class toward its historical tasks at every step”

The primary issue with this framing is that Rosa Luxemburg did not write or speak about “a revolutionary party of autonomy” at any point in her political career. She was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) for most of her life before its left-wing split into the USPD and then Spartacist League (later renamed the Communist Party of Germany, or KPD). Both organizations were mass parties who explicitly intended to lead the working class to overthrow the existing political order and form a new proletarian government in Germany, headed by elected party officials. Her point about the party being an instrument that puts the working class in power was perfectly in line with the existing Marxist orthodoxy. Consider this quote from the SPD’s leading theorist Karl Kautsky for comparison:

The socialists no longer have the task of freely inventing a new society but rather uncovering its elements in existing society. No more do they have to bring salvation from its misery to the proletariat from above, but rather they have to support its class struggle through increasing its insight and promoting its economic and political organizations and in so doing bring about as quickly as possible the day when the proletariat will be able to save itself. The task of Social Democracy is to make the class struggle of the proletariat aware of its aim and capable of choosing the best means to attain this aim.6

Luxemburg and Kautsky both demonstrate the function of the mass party: cohering the most militant and forward-thinking section of the working class into one organization and giving it the tools to win political power. If the party is not “outside or above the revolutionary process”, as CounterPower puts it, then it is coming to power through class leadership. “Providing the boldest elements in decision-making organs” is just a milder way of phrasing “winning political hegemony in the movement.” While it is right to be skeptical of potential opportunists and wary of inadvertently creating an unaccountable bureaucracy, CounterPower overcorrects by trying to avoid the question of leadership altogether. No amount of out-of-context quotes from historical revolutionaries can paper over that deficiency.

After painting an anarchist portrait of Rosa Luxemburg, CounterPower then calls upon the theoretical authority of actual anarchist Errico Malatesta:

We anarchists can all say that we are of the same party, if by the word ‘party’ we mean all who are on the same side, that is, who share the same general aspirations and who, in one way or another, struggle for the same ends against common adversaries and enemies. But this does not mean it is possible—or even desirable—for all of us to be gathered into one specific association. There are too many differences of environment and conditions of struggle; too many possible ways of action to choose among, and also too many differences of temperament and personal incompatibilities for a General Union, if taken seriously, not to become, instead of a means for coordinating and reviewing the efforts of all, an obstacle to individual activity and perhaps also a cause of more bitter internal strife.7

This is a markedly different approach to organization from the mass party model of Kautsky, Luxemburg, Lenin, et al. It is certainly more in line with the autonomists’ “area of the party” theory, but are the assumptions it is based on sound? The experience of the Bolshevik party securing state power and defending the proletariat from white terror, the Communist Party of Vietnam’s triumph over colonialism, the continued resistance to neoliberal imperialism in Cuba, and other achievements of the mass party model seem to indicate otherwise. Petty personal disputes and geographic distance are no excuse to abandon unified efforts to build socialism. If we take a scientific approach and compare the results of party-building trials throughout history to the results of those like Malatesta who deny the party’s role, the pattern is self-evident.

Lessons of History

CounterPower’s essay does an excellent job of considering the experiences of a vast number of different historical communist groups. Unfortunately, they do so without an ounce of reflection or criticism. They ask us to look at rival groups with opposing political strategies and conclude that both were right, regardless of whether either group actually achieved its aims. They mention the experience of many parties and movements—the KAPD in Germany, Autonomia Operaia in Italy, the MIR in Chile, the FMLN-FDR in El Salvador, the URNG in Guatemala, the HBDH in Turkey and Kurdistan, and more. We’re given the impression that each of these groups consciously agreed with the autonomists’ many parties model, and that each of these groups were successful enough to teach us mainly positive lessons to emulate. Upon closer inspection, it turns out this is not at all the case. For the sake of brevity, we will look at three examples.

Let us begin with the Communist Workers’ Party of Germany (KAPD). This party could be accurately described as a sect based on its low membership, extreme sectarianism, and history of splits. Its complicated lineage is as follows—its members began in the SPD, then split into the ISD, which then joined the USPD, which then split into the KPD, and then finally split from there into the left-communist KAPD. It functionally existed for about two years before splitting again into separate factions. It was quite literally a split of a split of a split that ended up splitting. It had around 43,000 members at its height in 1921, which was minuscule compared to the hundreds of thousands of workers in the mass parties (and that number immediately declined after the factional split in 1922).

The roots of the KAPD’s separation from the KPD lie in the events of the Ruhr Uprising. In 1920, a right-wing coalition of military officers and monarchists attempted to overthrow the bourgeois-democratic government of Germany. In response, the government called for a general strike, which the workers’ parties heeded. In the Ruhr valley, these parties took the strike a step further by forming Red Army units and engaging right-wing forces in open combat. However, these socialist militias were divided between three different parties and could not coordinate their efforts as well as their enemies who had the benefit of a clear leadership structure. The uprising was ultimately crushed when the bourgeois government made a deal with the right-wing putsch leaders and sent their forces to slaughter the workers of the Ruhr.

What lessons did the left-communists learn from this? From their perspective, KPD leaders had given up on the struggle by agreeing to disband Red Army units after the fighting looked to be in the enemy’s favor. Because of this, a split was necessary so the workers could be led by the true communist militants that would see things through to the end. In other words, the already divided proletariat needed a fourth party to further complicate the coordination of future actions. Two years later, this fourth party would then split into two factions. Lenin had this to say about the KAPD:

Let the ‘Lefts’ put themselves to a practical test on a national and international scale. Let them try to prepare for (and then implement) the dictatorship of the proletariat, without a rigorously centralised party with iron discipline, without the ability to become masters of every sphere, every branch, and every variety of political and cultural work. Practical experience will soon teach them.8

Unfortunately, Lenin was overly optimistic. Rather than having time to learn from their mistakes, the divided forces of the working class were brutally crushed by the united forces of the right. The Nazis rose to power, and fascism reigned until the Soviets took Berlin in 1945. This does not mean there is nothing we can learn from the KAPD—quite the opposite is true. There may be some diamonds in the rough, but most of the lessons we can learn from the left-communists of Germany are examples of what not to do. Fortunately, in the updated version of their essay, CounterPower scrubbed any mention of the KAPD. Whether this was due to a genuine reassessment of their example or simple editorial limitations, the new version is much stronger without the ill-fated German sectarians.

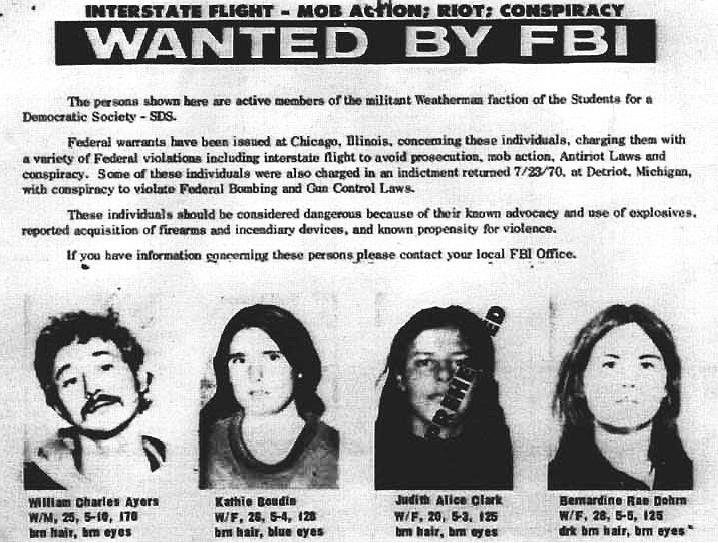

Despite their positive appraisal of the KAPD, CounterPower is not a left-communist sect. They are autonomists, and in order to understand their answer to the party question we must take stock of their movement forebears. Autonomia Operaia was a workers’ movement in Italy during the period known as the “Years of Lead”. This period lasted from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, and was marked by violent clashes between right and left-wing paramilitary forces. It is worth noting that much of this violence was either planned, supplied, or encouraged by the CIA and its “Operation Gladio”, although that is not relevant to our discussion here. Autonomia Operaia was mainly active from ‘76 to ‘78, and was made up of many smaller socialist groups including Potere Operaio, Gruppo Gramsci, and Lotta Continua. Each group was strongly opposed to unifying into one party, preferring instead to maintain their autonomy and pursue different tactics to work towards their shared goal of social revolution.

In the end, this worked out in much the same way as it did for the sectarians in Germany decades earlier. Thousands of militants were arrested, hundreds fled the country, many were killed, and most of those who remained dissolved into terrorist groups like the Red Brigades and parliamentary parties like Democrazia Proletaria. Neither the autonomist terrorists nor the autonomist politicians were able to move beyond the failures of the earlier autonomist movement. In retrospect, the autonomists ended up replicating the sect form (albeit with some anarchist-influenced language) and suffered the familiar consequences of this organizing technique. It is worth noting that after misappropriating numerous mass parties (the Alabama chapter of CPUSA, the Bolsheviks, Rosa Luxemburg’s KPD) as successful examples of the “parties of autonomy” model, CounterPower leaves out any mention of Autonomia Operaia in the updated version of its essay. This is somewhat understandable as the movement collapsed within two years and failed to achieve its aims, but it is still dishonest. If failures are glossed over rather than rigorously examined, we are doomed to walk blindly into past mistakes. In this regard, CounterPower’s update to their essay does more to obfuscate the party question than answer it.

That said, Autonomia Operaia activists had valid criticisms of the Communist Party of Italy and could have created an alternative to lead the proletariat to victory. This is the positive lesson we can learn from them: when the “official” communist party of the nation abandons its principles, it can sometimes be worthwhile to build an alternative organization. However, they chose instead to create a loose collective of semi-aligned communist clusters which failed to coordinate their actions and create meaningful change. Had they taken on the arduous task of debating long-term strategy and forging programmatic unity, things may have turned out differently. This is the primary lesson we should learn from the Italian autonomists: a proletarian victory requires structure, democratic discipline, and unity of action.

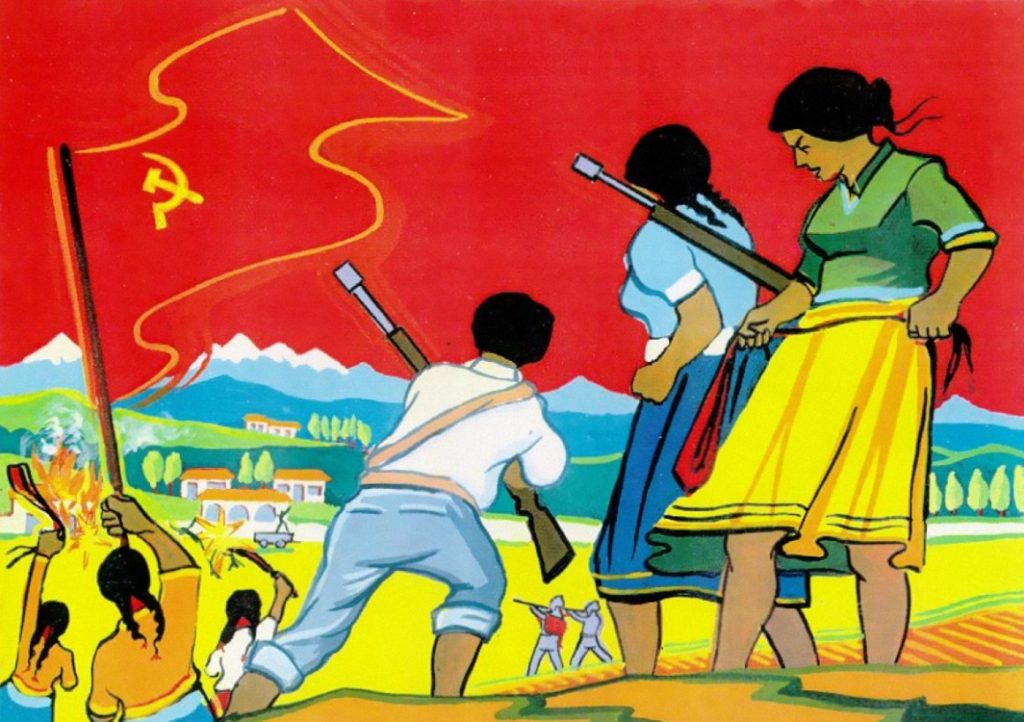

Although not directly influenced by Autonomia’s answer to the party question, the FMLN-FDR of El Salvador could be theorized as an example of an “area of the party”. As CounterPower pointed out in their essay, this network was composed of five revolutionary parties and a number of mass organizations and civil society institutions who worked together in loose cooperation towards revolution. It ultimately failed, and CounterPower makes two interesting claims about its dissolution: that the failure was due primarily to the popular front reformism of the PCS (one of the five member parties) and that its downfall does not tarnish its status as a positive example of the area of the party in action. These claims do not fare well under the spotlight of historical scrutiny, particularly when shined on the brutal internecine violence that destroyed any semblance of unity within the movement by 1983.

CounterPower’s assessment of the FMLN identifies the PCS (Communist Party of El Salvador) as the weakest link in the chain, and the FPL (Farabundo Martí Liberation People’s Forces) as the strongest. In many ways, this is true, as the popular front strategy of the official communist parties has consistently ended in disaster the world over and the FPL was the most powerful and trusted party in El Salvador for a time. However, this is not the whole picture. Genuine political disagreements were often buried or papered over to maintain an artificial unity, and the ensuing tension was bound to boil over. While our autonomist comrades say the FMLN established a harmonious “mechanism of communication, coordination, and cooperation among the various politico-military organizations”, the reality is far grimmer. In its disagreement with other parties advocating negotiations with the Salvadoran government, the FPL resorted to gruesome assassinations to enforce its will on the rest of the FMLN. In April of 1983, FPL cadre Rogelio Bazzaglia murdered pro-negotiation leader Ana Maria with an ice pick, stabbing her 83 times. Although there was an attempt to blame the CIA or another party within FMLN, when presented concrete evidence of Bazzaglia’s guilt, FPL leader Salvador Cayetano Carpio promptly wrote a suicide note and shot himself in the head. With its most trusted leaders either disgraced, dead, or both, the FMLN lost steam after many members left the network in disgust. Along with this exodus of valuable cadre went all the legitimacy of the anti-negotiation faction, and so by 1989 even successful military offensives could do nothing more than bring the Salvadoran government to the negotiation table.9 The revolutionary potential of the FMLN died with Ana Maria, and her murder demonstrates how the “area of the party” approach only ends up recreating the problems of the sect form.

The Marxist Center

The US communist movement is essentially home to three different camps regarding the party question. Those who wish to see the movement divided into bureaucratic sects (with the belief that their particular sect is the One True Party) are on the right. Those who wish to see the movement divided into loosely aligned autonomist sects (with the beliefs outlined in CounterPower’s writing) are on the left. Those of us in the center are advocating a qualitative break with the sect form: the foundation of a mass party of organizers. This idea is often associated with a number of inaccurate claims—for instance, we are frequently lumped in with those who wish to replicate the worst aspects of the DSA model, where anyone can join the organization at any time for any reason without even committing to Marxist politics. We are also often accused of wanting to create a dogmatic bureaucracy of staunch Marxist-Leninists who will run the party as they see fit without input from membership. Neither of these claims are true.

In fact, what we desire is a party made and run by the masses themselves. Years of labor-intensive organizing will be necessary to make this happen, as the masses cannot be reached and welcomed into the socialist movement any other way. Tenant and workplace unions, unemployed councils, harm reduction efforts, solidarity networks, and other forms of “mass organizations” (in addition to independent electoral efforts) must be formed and rallied around a common political pole. In order for this pole to exist in the first place, the organizers engaged in mass work must debate and discuss until they articulate and agree on a comprehensive political program. In order for these debates and discussions to produce a clear program, the organizers have to see themselves as part of a common organization aimed at a shared goal. When each of these elements fall into place, something completely unique to the US left will be born: a mass party committed to praxis, programmatic unity, and democratic discipline.

By praxis, we understand a long-term commitment to building, growing, and maintaining the kinds of mass organizations detailed above. By programmatic unity, we mean collective acceptance of a comprehensive set of answers to long-term strategic questions, forged in an extended process of comradely debate and compromise. Ideally, this would take the form of a minimum-maximum program like those laid out and critiqued by Marx, Engels, and others in the first two Internationals.10 The minimum demands are structural reforms that communicate to the working class exactly how our efforts will improve their lives and empower them at the political level. Demands like guaranteed healthcare and housing, eliminating the Electoral College, Senate, and Supreme Court, disbanding the police and forming workers’ militias, ensuring union representation, and more would bring supporters into the fold and give us access to valuable comrades and organizers. They are chosen in such a way that when every demand is met, the proletariat has seized political power from the bourgeoisie and becomes the governing class of society.

With this done, the new workers’ government can focus on fulfilling the maximum demands, epitomized as communism, which would eradicate the last vestiges of capitalism and transition to a socialist mode of production. Establishing unity on long-term questions of strategy is far superior to enforcing a “party-line” on day-to-day issues and theoretical minutiae. It allows us to collaborate and exert the greatest possible combined strength of the working class in its diverse struggles without splitting over short-term tactical disagreements like “should we partner with this NGO on this tenant organizing project?” or subcultural arguments like “who was in the wrong at Kronstadt?” It also does not require agreement on “tendency” labels (such as Marxist-Leninist, anarchist, left-communist, etc). As our organizations grow, the need for a commonly accepted program will only increase. Finally, by democratic discipline, we refer to the old axiom “diversity of opinion, unity of action”.

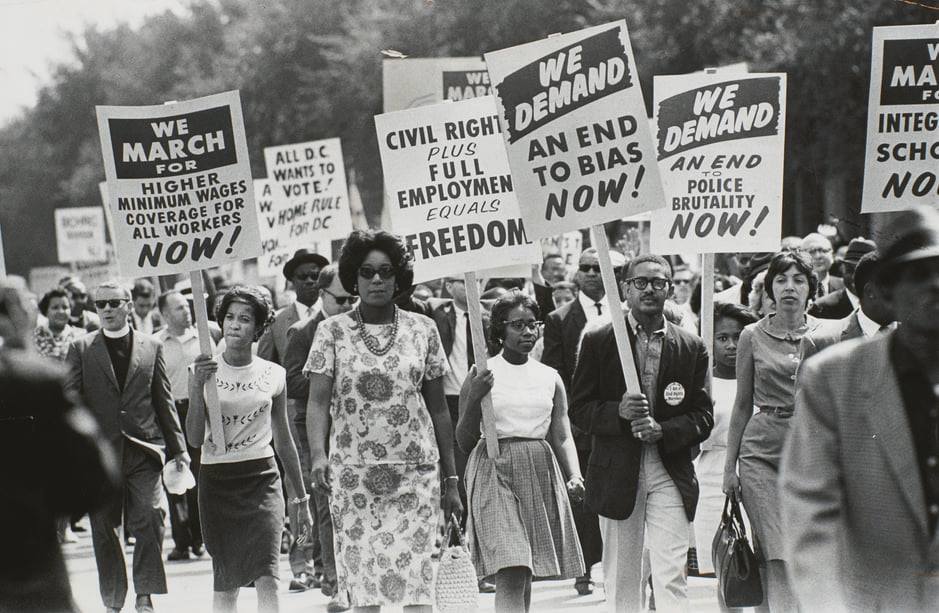

These three principles are absolutely essential for the functioning of an effective and battle-ready proletarian party. As we have seen, the organizational forms of sectarians and autonomists (like the KAPD and Autonomia Operaia respectively) crumble under pressure whereas mass parties regularly weather brutal repression. No better example of this can be found in US history than that of the Alabama chapter of the CPUSA:

The fact is, the CP and its auxiliaries in Alabama did have a considerable following, some of whom devoured Marxist literature and dreamed of a socialist world. But to be a Communist, an ILD member, or an SCU militant was to face the possibility of imprisonment, beatings, kidnapping, and even death. And yet the Party survived, and at times thrived, in this thoroughly racist, racially divided, and repressive social world.11

While other cases of this phenomenon (the Russian Communist Party, the Chinese Communist Party, and others) have been historically prone to corruption, preventative measures can be taken to ensure the party retains its mass character even after smashing the state and beginning socialist reconstruction. The most immediate step in this process is the collaborative drafting of and universal agreement on a party-wide Code of Conduct. This will facilitate the development of a comradely culture that balances rigorous critique and debate with an environment of pluralism and interpersonal care. In addition to understanding how to have a one-on-one organizing conversation, we should also strive to be well-versed in skills like listening, openly sharing feelings, assuming good faith in arguments, making sincere apologies, and offering support to comrades struggling with personal issues. None of these can be learned by accident in the alienated social spaces created by capitalism, so we must make a deliberate effort to establish these norms in our organization.

Another would be taking seriously the moral dimensions of Fidelismo’s contribution to Marxism. In stark contrast with both Stalin’s iron fist and Allende’s naive pacifism, Fidel Castro’s leadership of the Cuban revolution combined violent insurrection against the state with peaceful political maneuvering in the revolutionary movement. Over the course of protracted struggle on both fronts, the July 26th Movement was able to defeat the state militarily and construct a democratic mandate for political hegemony. Because Fidel and his comrades took the ethical implications of revolutionary struggle seriously, they were able to achieve victory without recourse to war crimes against the enemy or lethal violence against political competitors within the movement.12 This commitment to moral conduct during violent struggle did not stop them from winning the war. In fact, it allowed them to win the peace. This strategy allowed Cuba to begin building socialism after national liberation without the deadly internecine conflicts that plagued other revolutionary movements (notably including the FMLN). It is crucial that we embrace this legacy by constructing an ethic of revolution for our time. More steps beyond these will of course be necessary, and their exact nature will become clear as we work towards the realization of a comradely culture together.

Perhaps the strongest indicator of the need for a mass party is the fact that the most advanced sections of the US labor movement are already calling for the establishment of a workers’ party. In its recent pamphlet Them and Us Unionism, United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) wrote:

Throughout our history, UE has held that workers need our own political party. In the 1990s, UE worked with a number of other unions to found the Labor Party, under the slogan ‘The Bosses Have Two Parties, We Need One of Our Own.’ Although the Labor Party experiment was ultimately unsuccessful, UE members and locals have been active in numerous other efforts to promote independent, pro-worker alternatives to the two major parties.13

Other labor unions like ILWU and the Teamsters have produced leading organizers who share UE’s commitment to independent worker politics. People like Clarence Thomas, who helped organize the Juneteenth port shutdown on the West Coast earlier this year in solidarity with the George Floyd uprising, Chris Silvera, who chairs the National Black Caucus in the Teamsters, and many more can be found among them. These influential voices of the labor movement have united in Labor and Community for an Independent Party, stating:

We must build democratically run coalitions that bring together the stakeholders in labor and the communities of the oppressed, so that they have a decisive say in formulating their demands and mapping out a strategy. Most important, we need to put an end to the monopoly of political power by the Democrats and Republicans. The labor movement and the leaders of the Latino and Black struggles need to break with their reliance on the Democratic Party and build their own mass-based independent working-class political party.

While it is certainly possible that these efforts could lead to the establishment of a reformist labor party, it is precisely this possibility that behooves us to get involved. Any union that recognizes the need for independent proletarian political action outside the shop floor can be considered “advanced” compared to business unions aligned with the Democratic Party, and relationships with them should be built as part of a communist intervention in the labor movement. As Marxists, we have a duty not only to organize our class but to bring theoretical clarity to its most active champions. If we continue building strong proletarian fighting organizations and elaborate our vision in a comprehensive program, we will be positioned to guide labor and community leaders of all stripes to the creation of a truly communist political party.

Ultimately, the disparate sects within Marxist Center and the local chapters of the DSA must form tighter bonds and consider internal reforms that would allow us to build the party our class requires. In doing so, we should seek to unite as many far-flung collectives and mass work projects as we can in order to become a true threat to bourgeois hegemony. While staying divided in a loose federation may seem like a viable model to some, history shows that it is not. The autonomists and anarchists in our ranks are dedicated organizers doing valuable work, and we should be grateful for that. However, we would be doing ourselves and them a disservice if we did not offer a comradely critique of their organizational models.

Communists will always find strength in unity.