What is power and how do we build it? Amelia Davenport argues that power must be built through the organization of mass communist institutions independent of the state.

The Question of Power

Where does power come from? Mao Zedong1 claimed it “grows out of the barrel of a gun”, while Bill Haywood claimed it comes from the folded arms of workers refusing to produce.2 For Saul Alinsky, power exists in the minds of others as much as in your real capacity. He said, “power is not only what you have but what the enemy thinks you have.”3 Is power the material ability to promote a viewpoint by force? Is it the ability to remove the power of your enemy to meet their aims? Or is the perception of the threat you pose to your enemy’s power decisive?

While the first two propositions put power directly in your hands, the third does not. Increasing the perception of your power merely magnifies the efficacy of existing power you built. This doesn’t mean that the projection of power is not important tactically; it can allow a stronger negotiating position in fights where you cannot achieve total victory, like in day-to-day union struggles. But it can be tactically ill-advised to seem strong. Sometimes it is better for your strength to be underestimated, like in mobilizations against police. What defines your strength in the projection of power is your ability to shape perception. It’s not simply a function of how powerful you seem. Power is the independent capacity to make changes in the world without relying on the strength of other forces.

In the socialist movement the question of power is paramount. We are ostensibly for building workers’ power, but what that means in concrete terms is highly contentious. For many self-described socialists and Marxists, making the lives of workers in capitalism easier by leveraging infrastructure to win reforms is building power. Many in this camp call themselves “base-builders.” This is a term originally developed by anti-electoral Marxists. But electoral Marxists adopted it because they saw creating mutual aid networks and workplace organizations, or “bases,” as a means to increase electoral capacity in the long run. But what kind of “power” are you building if your aim is to use the capitalist state as a vehicle?

When you lobby a legislature to put legal restrictions on capitalism, what you’re really doing is begging for the cops to do the work of our class. You’re asking the cops to go in and arrest people who refuse to comply; you’re asking the capitalists to pay fees which are, in effect, donations to the imperialist military. You’re making a lot of noise and creating a lot of pressure, but once the campaign is done, everything goes back to equilibrium with no new lasting power on the side of the workers. In many cases, financial penalties levied on companies are simply factored into the cost of doing business. Real power remains firmly in the hands of the state and the capitalist class, with only a slight shift on the balance sheet between the two. Trying to use the power of the capitalist state is an admission that you have no real power.

One could object that this applies to unions as well: that union struggle leaves the power with the boss at the end of the day, and that tactics like strikes are merely a form of lobbying. But while there is a superficial similarity, union struggle and parliamentary struggle are entirely different: unions can create permanent structures that actively include workers in the fight for better conditions; a union committee constantly builds up the skills and capacity of the workers in a shop, and shows workers that they have the ability to force changes directly rather than relying on third parties. This permanent structure created by unions, when in the hands of revolutionaries, serves as the nucleus of the future organization of labor under socialism. By seeking to unite workers across industries into one democratically controlled structure, they set the stage for the future administration of the labor process in the future socialist commonwealth.

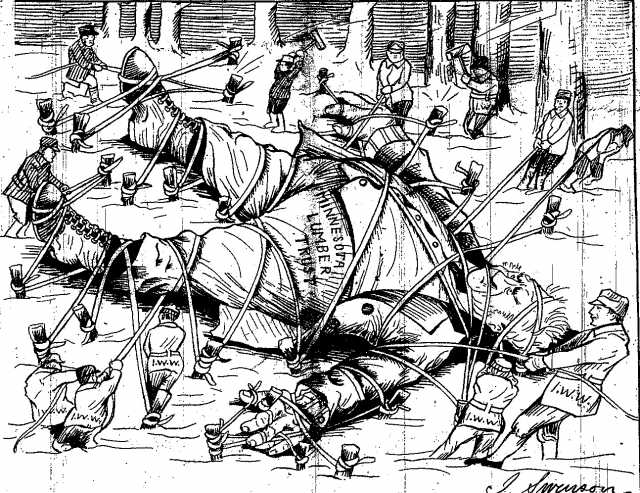

To be sure there are “unions” that actively work against this principle and are more like dues-collecting private insurance agencies than organs of class struggle. This is the difference between “red” unions and “yellow” unions: red unions are based on class struggle and, while they include workers with many different views, require their members to oppose the wage-system; yellow unions are based on the idea of a “fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work” and the unity of interests between capital and labor. Yellow unions seek to benefit members of a particular trade or industry at the expense of all others, while red unions fight for all members of the working class even if they’re not in the union. Where yellow unions rely on government arbitration and the courts, red unions enforce their demands themselves with action on the shop floor. If a boss goes back on his promise of higher wages, workers in a red union take matters into their own hands to put stress on his pocketbook through direct action; in a yellow union, they rely on the state as a third party to enforce contracts.

Red unions have existed in many times and places in the class struggle: the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—particularly in its 1905–1945 heyday, but also now; United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE); the early Irish Transport and General Workers Union; the SI Cobas in Italy; the National Confederation of Labor (CNT) in Spain; and both the Spanish and French General Confederation of Labor. Yellow unions include all existing American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) unions—no matter how many Marxists and Anarchists are in their leadership—and the vast majority of unions worldwide.

The difference between red unions and yellow unions is not always clear, and one can be transformed into the other. There are often red caucuses within yellow unions and reactionary currents in red unions. Class struggle takes place within the union just as much as between the union and the boss. As unionists occupy businesses that have failed due to capitalist crisis they can create worker-run firms—as UE did when they founded New Era Windows—and they can push for greater autonomy for workers in running production under capitalism. While red unions don’t totally eschew contracts and benefits, their focus is on creating long-term institutional power for workers. To be sure, the building of red unions is a long and arduous task, one which requires the building of capacity that revolutionary socialists are only now starting to regain. But they remain one important part of the overall struggle against capitalism.

In the case of unions, as in the case of armed struggle, power requires collective action. Mao’s dictum about power coming from the gun is only true if there are many guns. Direct action on behalf of the masses can take many forms: industrial sabotage, individual terrorism, blockades and other tactics. The act of individual terrorism is a tactic that has long outlived its ability to effect social change, and the actions of a lone worker to sabotage industry in a demand for rights have no beneficial effect. As Leon Trotsky argued in “Why Marxists Oppose Individualist Terrorism”:

In our eyes, individual terror is inadmissible precisely because it belittles the role of the masses in their own consciousness, reconciles them to their powerlessness, and turns their eyes and hopes towards a great avenger and liberator who some day will come and accomplish his mission. The anarchist prophets of the ‘propaganda of the deed’ can argue all they want about the elevating and stimulating influence of terrorist acts on the masses. Theoretical considerations and political experience prove otherwise. The more ‘effective’ the terrorist acts, the greater their impact, the more they reduce the interest of the masses in self-organisation and self-education. But the smoke from the confusion clears away, the panic disappears, the successor of the murdered minister makes his appearance, life again settles into the old rut, the wheel of capitalist exploitation turns as before; only the police repression grows more savage and brazen. And as a result, in place of the kindled hopes and artificially aroused excitement comes disillusionment and apathy.4

This same principle applies to anarchist “direct action” which—unlike true direct action, which is necessarily collective and organized—is really ‘the propaganda of the deed’ renamed. Propaganda of the deed was the strategy of small cells of anarchists engaging in terrorist actions like bombings, assassinations, sabotage, and so on to galvanize the passive masses into revolutionary consciousness by showing them the ruling powers were weak. Anarchist “direct action” is carried out by “affinity groups.” Affinity groups are small autonomous cells of anarchist militants that self-organize, they are inherently vanguardist, in a much more profound sense than most self-described vanguard parties. When affinity groups try to engage in labor struggle they only alienate the majority of workers. They are elitist because of their rejection of the democratic principle. Political action requires mass organizations, not militant minorities. This model is not exclusive to anarchists, some Council Communists and other Marxist currents also reject the creation of permanent democratic workers bodies on the shop floor. For example, the journal Intransigence hosts authors sharing in the insurrectionary anarchist view. A union grows the collective organizational capacity of the working class. It requires a majority of its members to be fully on board with its vision to work.

This principle is also why the Leninist “militant minority” model is flawed: rather than make the whole union socialist, the union is kept formally apolitical while a politicized cadre of radicals pushes the rank and file into more advanced positions and militant tactics. Unless the radical committee seeks to directly include all union members in the class struggle consciously, they will at best be the equivalent of government socialists within the union. Radical unionists might capture leadership in a yellow union, but without changing the nature of the union, in practice they become business unionists. This is proven by the century of Communist and Anarchist leaders in the AFL having utterly failed to make more than ephemeral gains in radicalism. The same is true of all areas of the working-class struggle: workers’ institutions seek to include as many people as possible in their administration and activity, rather than promoting the idea of the “savior” which NGOs unconsciously promote.

Unlike red unions whose primary—but not exclusive—function is to negotiate with the boss, red parties do not have to negotiate with the state as a primary task. The task of red parties is to prepare for a contest of power between the working class and the capitalist class. Building power requires clear strategy and comprehensive analysis; without understanding a situation one’s ability to shape outcomes within it are limited. The task of a workers’ party is to forge the working class into a political category for itself, set forth the class’ aims, develop the requisite theory to understand how to realize those aims, and help build forms of class power capable of defense from—and inroads on—capitalist domination.

Power is the capacity to strategically leverage collective action in order to effect desired changes; it can manifest either as coercive force positively applied or as a negative withdrawal of collective labor. Often, power is expressed in both ways at once: scabs who threaten the livelihood of strikers are met with collective force and revolutionary civil wars require mutinies in the state’s forces. Building resilient forms of working-class power requires us to be clear about our methods if the owning class is to be overthrown.

The Road to Power

Historically, the socialist movement has generally used two methods of articulating its aims: the minimum-maximum program and the transitional program.

The minimum-maximum program was created by the early Marxists to synthesize between two existing—but wrongheaded—approaches to creating demands: the “Possibilists” created programs which laid out demands they saw as winnable and refused to agitate for more radical changes, lest they be unelectable; On the other hand there were the “Impossibilists,” whose programs consisted of the immediate abolition of capitalism and other necessary tasks of socialism which could never be passed by a bourgeois legislature. The Impossibilists saw the role of elections as purely agitational. By combining the two approaches into one unified whole, the Minimum-Maximum program had one section which laid out the ultimate goals of the revolution, and another section which advanced winnable objectives that the capitalist state could concede on.

The first example of a minimum-maximum program was the Program of the French Workers’ Party of 1880. Based on demands adopted from the workers’ movement, Karl Marx and Jules Guesde lay out a concise description of the aims of communism in the preamble, then list a set of demands that are winnable within capitalism. The vast majority of these demands are negative in relation to the state: freedom of the press, the abolition of the army, abolition of indirect taxes such as tariffs and taxes on commodities. Others are negative in relation to capitalism: prohibiting interference by bosses in union activity, banning wages below a minimum amount, mandating the reduction of the working day.5 The program also demands state funding of child rearing, equal pay for equal work between the sexes and races, education standards requiring scientific instruction, the transformation of state-owned enterprises into worker-managed firms, and workplace accident insurance funded by bosses and controlled by the workers, among other provisions.

While the authors advocate the use of the state to regulate employers and education, it is clear that their primary concerns were with limiting state power. Insofar as they called for the expansion of the state, it was to constrain capitalist abuse of the working class, and insofar as they demanded payment from the state for childcare, it was without bureaucratic restrictions. Five years earlier, in the Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx wrote:

“Elementary education by the state” is altogether objectionable. Defining by a general law the expenditures on the elementary schools, the qualifications of the teaching staff, the branches of instruction, etc., and, as is done in the United States, supervising the fulfillment of these legal specifications by state inspectors, is a very different thing from appointing the state as the educator of the people! Government and church should rather be equally excluded from any influence on the school. Particularly, indeed, in the Prusso-German Empire (and one should not take refuge in the rotten subterfuge that one is speaking of a “state of the future”; we have seen how matters stand in this respect) the state has need, on the contrary, of a very stern education by the people.6

As a self-conceived “Marxist”, Jules Guesde did not believe in the demands he helped author and simply saw them as a form of bait to lure workers from the bourgeois Radicals. He believed in immediate revolution without any compromise. Guesde’s refusal to take seriously the demands for expansion of the democratic rights of workers led Marx to declare “I am not a Marxist”7 if the “revolutionary phrasemongering” Guesde was doing was Marxism.

Eleven years later, the German Social Democratic Party issued the Erfurt Program. It represents a key milestone in the development of the minimum-maximum program. It is considered the first fully Marxist program of German Social-Democracy. Before it was published though, Friedrich Engels wrote an in-depth critique8 of what he saw as the ghosts of Lasalleanism9 and “state socialism” within the program. The earlier draft called for the state to take control over areas like medicine, failed to call for the expansion of democratic institutions, and made a number minor theoretical errors. In the final draft, after Engels’ criticism, the demands for nationalization of medicine, dentistry, the bar, midwifery, and so on were transformed into demands that they become free. This is important because it opens the door for non-state solutions like worker or community-controlled healthcare. But the fact that the demand was initially for state ownership, that room for nationalization remained in the program, and that the demands were aimed at the state represented a creep forward of government socialism— “state socialism,” as Engels and other early Marxists called it. With the deaths of Marx and Engels, their influence could no longer stymie the transition of social democracy from revolutionary socialism to government socialism.

The minimum section of the Social Democratic program—comprised of demands for concessions from the state—degenerated from winnable reductions in state or capitalist power to winnable concessions for the “improvement of workers’ lives.” Instead of seeing the state as hostile terrain in the class war, it became a contestable field which the workers’ party could occupy and from which it could annex resources for the working class. Instead of looking at power sociologically, the social democrats imagined a linear formula where the power of the workers was measured by how much social surplus they got vs how much the capitalists got. While many “Orthodox Marxists” still held out hope for revolution, their practice was indistinguishable from that of the Revisionists. The road the social democrats trod was not to power, but rather into the belly of the powerful.

Like the Orthodox Marxists and the Marxist-Leninist parties that split from them, the Trotskyists of the 4th International saw the state as the locus of legitimate social power and a field which was to be contested rather than hostile terrain. Unlike the Orthodox Marxists and Marxist-Leninists, their successors do not choose minimum demands that are winnable under capitalism. Instead, they adopted a policy reminiscent of Jules Guesde’s “revolutionary phrasemongering”: the transitional program. Like the minimum program, the transitional program begins with demands which have organically emerged in the course of the workers’ struggle. It takes these demands and goes further, pushing workers to adopt slogans which call for concessions that are increasingly radical but sound reasonable from the perspective of workers.

But these slogans are never intended to be acted on. In fact, these transitional demands are chosen specifically because they’re impossible to realize within capitalism. Demands are chosen for their “educational” value rather than their chances of success. Trotsky puts it, “By means of this struggle, no matter what immediate practical successes may be, the workers will best come to understand the necessity of liquidating capitalist slavery.”10 For example: if workers and their unions are calling for a phased-in raise of the minimum wage, the Trotskyists will not only demand a higher wage but also that the raise be immediate, because they believe this demand can’t be enacted. After the increasingly-militant workers lose their fight for the transitional demand, the Trotskyists believe this will show them that the capitalist state and reforms can’t bring about the kinds of change needed for workers to realize their interests, which will push them towards socialism.

Another example in the original outline of the transitional method is the call for nationalization. Despite the fact that Trotsky is explicit that the nationalization of industries by the bourgeois state have nothing to do with socialism, he claims that adding empty slogans about workers’ control will make the demand revolutionary:

In precisely the same way, we demand the expropriation of the corporations holding monopolies on war industries, railroads, the most important sources of raw materials, etc.

The difference between these demands and the muddleheaded reformist slogan of “nationalization” lies in the following: (1) we reject indemnification; (2) we warn the masses against demagogues of the People’s Front who, giving lip service to nationalization, remain in reality agents of capital; (3) we call upon the masses to rely only upon their own revolutionary strength; (4) we link up the question of expropriation with that of seizure of power by the workers and farmers.

The necessity of advancing the slogan of expropriation in the course of daily agitation in partial form, and not only in our propaganda in its more comprehensive aspects, is dictated by the fact that different branches of industry are on different levels of development, occupy a different place in the life of society, and pass through different stages of the class struggle. Only a general revolutionary upsurge of the proletariat can place the complete expropriation of the bourgeoisie on the order of the day. The task of transitional demands is to prepare the proletariat to solve this problem.11

Trotsky goes on to argue that a key demand of the workers’ movement is the statization of banks, correctly ascertaining that the control of financial capital is essential for the economic planning of capitalism and that it would be good for the banks to become state assets if the working class were in command. The sleight of hand is that the transitional program demands the nationalization of banks now, even without a workers’ party in command, otherwise it would be a maximum demand, not a transitional demand.

The transitional program, as originally articulated by Trotsky, is not without its merits. One of its key planks is the call to create revolutionary workers’ militias out of the labor union struggle, while others include the opposition to imperialist wars. While the “transitional method” has been a resounding failure, it should be remembered that Trotsky and his contemporary allies were crucial members of the revolutionary working-class movement who must be learned from critically. The impulse to advance towards revolution in the face of the 3rd International’s backslide into reformism and alliances with liberals is the animating force behind why the transitional method was developed and that should be commended. But just as implicit in it are the very same deformations that led to the failures of the Marxist-Leninist movement; the transitional method adopts a schoolmaster’s view of the working class.

Not having the virtues of being lifelong communists in a period of revolutionary upheaval, contemporary Trotskyists only inherit the sins of their prophet. Take for instance Socialist Alternative in Seattle who used the slogan of 15 Now to grow their organization. But despite claiming they would fight for a ballot initiative regardless of what minimum wage law the city adopted, they abandoned the campaign after the city passed a lesser, gradual minimum wage increase. In an about-face worthy of any Stalinist, Socialist Alternative launched the disastrous campaign for Jess Spear12 to take a seat in the Washington State House of Representatives instead of keeping their promise. If the demands of the transitional program are enacted, the Trotskyists believe this will create a “crisis of leadership” in which the capitalist class will rebel against the state and allow their party to swoop in, backed by the militant working class and shepherd the workers towards socialism.

The transitional method was developed during a crest in revolutionary socialist organizing as a means to go beyond the reformist limitations of the minimum program. When Trotsky proposed it, there was every reason to believe a crisis of leadership could emerge and that in a short time period the working class might seize control. But time has shown that the method has failed to do anything other than co-opt revolutionary struggles and disillusion militants. It’s a cynical method that considers the working-class too stupid to realize that revolution is necessary without being led like sheep into the den of the wolves. When the Trotskyist parties do not degenerate into irrelevant sects, they liquidate into the bourgeois establishment, playing power-broker between the unions and grassroots campaigns they successfully co-opt and the liberals. In order to maintain their position, they act to police radical protests and contain them so they can be leveraged to increase their party’s power. The transitional method obscures all of these opportunistic turns by allowing militant rhetoric to substitute for revolutionary action. When questioned, Trotskyists will respond that we are not ‘in a revolutionary situation’ and conflate the improvement in their party’s position with the improvement of the position of the working class as a whole.

Socialist Alternative, in particular, has a long history of this behavior, including during the protests against President Trump’s travel ban, when they prematurely called the protest off while endangering militants. They co-opt tenant movements and push them to adopt the call for demands like rent control—which they know is not a possible reform on the municipal level in Washington State. They demand their militants refrain from joining red unions like the IWW and even from reading the newspapers of other parties. This is not by any means limited to Socialist Alternative or its affiliates in the so-called Committee for a Workers’ International. Trotskyist parties have been using the same sort of tactics since the 1930s. While these organizations have often made heroic contributions to the class struggle, winning concessions for workers and fighting racism in the auto industry, their methods undermine their success, showing little for their work in the long run.13 By setting themselves up as the leaders and schoolmasters of the working class, the purpose of the party transitions from advancing the struggle to advancing the careers of party functionaries.

Neoliberalism is State Capitalism

The old British television show Yes Minister illustrates the nature of the capitalist state. Every time Jim Hacker—a bumbling parliamentary minister with dreams of grandeur—sets out to create his legacy with some sweeping reform of the system, his aide Sir Humphrey Appleby is there to dissuade him, leveraging considerable bureaucratic inertia to neuter Hacker’s most determined attempts. In the show, Hacker and his staff share a particular set of jargon exemplified in their use of the word “courageous”: where a policy being “controversial” means Hacker could lose votes, a policy that is “courageous” would cost him the election. It is only by doing absolutely nothing of substance while both making the appearance of progress and keeping vested interests happy that Hacker is able to ascend to the high office of prime minister.

The capitalist state is sociologically and structurally aligned with the capitalist class, regardless of the beliefs or intentions of individuals working inside it. Not only do politicians, high-level bureaucrats, and other officials become educated and socialize in the same environments, go to the same golf courses, read the same newspapers, and share meals with the capitalist and managerial classes; their structural interests are in the maintenance of the overall system and preservation of the status-quo.

While it is true that leaders like Franklin Roosevelt, Margaret Thatcher, and others have successfully made dramatic changes to the functioning of the state and its role in society, they did so during periods of capitalist crisis. Roosevelt expanded the reach of the bourgeois state into private property, while Thatcher expanded the reach of private capitalists into public institutions. But, they share an essential unity. Both were seeking to adopt the state to a new underlying reality for the interests of preserving capitalism, rather than to make progress for its own sake, which is why the state and private-sector bureaucrats were able to go along with it. Of course, all bureaucrats have certain imperial ambitions about the domain of their own agency or office, but they are kept in check by their rivals in similar positions, much like feudal lords squabbling over land. Their careers, 401k’s, and lifestyles are inextricably linked to capitalism, and if they consciously work against the system they will cease to hold those jobs.

This kind of loyalty and institutional interest doesn’t vanish because the majority of people in the legislature claim to support socialism; instead, those legislators are forced to confront the reality of what’s “possible” to do in their offices. When politicians do try to create radical legislation which isn’t aligned with the interests of capitalism, either they are removed by force—like in the case of Chilean President Salvador Allende, who was ousted from power by a democidal military coup—or undermined by other arms of the government and society controlled by the capitalist class—as during the “socialist” government of Clement Attlee.

It’s not simply a matter of having better or more radical bureaucrats take control: the very foundations of the state in civil and common law are created of, by, and for the ruling class. It’s not just that radical bureaucrats would be sacked for trying to make socialist changes, (as they certainly would). In order for socialism or the rule of the working class to exist, their very jobs would need to be abolished. Every single agency needs to be radically restructured far beyond what is possible without the kind of power it takes an armed revolution to deploy. These bureaucracies are the product of the social division of labor and the estrangement of the collective power of humanity. They represent the administration of people, while socialism is the administration of things by the people.

To be sure, the rule of the working class requires a state and some level of institutionalized application of power. But this is not a state in the truest sense, as both Engels and Lenin pointed out. A workers’ state, as Lenin formulated it, is a “semi-state” whose goal is its own abolition.14 While a true state maintains a professionalized body of armed men to enforce class rule, a workers’ state is maintained by the armed working class, even if it may use some professionalized forces in the course of revolutionary struggle. Likewise, a workers’ state generalizes administration and the skills necessary to administer society as much as possible rather than condensing social power within a stratum of professional bureaucrats.

After WWII in Britain, the Labour Party came to power and dramatically expanded state control of industry. As many as 20% of British workers were employed by the state, particularly in key industries which represented the “commanding heights” of the economy: coal, banking, energy, rail, and eventually steel. Even against the Tory war hero Winston Churchill, the public voted in a landslide for Clement Attlee’s vision of British socialism:

a mixed economy developing toward socialism…. The doctrines of abundance, of full employment, and of social security require the transfer to public ownership of certain major economic forces and the planned control in the public interest of many other economic activities.15

While many of the Labourites had sincerely believed that those nationalizations were a step toward a planned economy, by 1947 even the furthest-left Labour ministers like Ernest Bevin dismissed planning in favor of “working things out practically” as their industries were turned into “public corporations” that operated identically to private firms— (except that they were responsible to the state rather than to investors).16 The only exception was healthcare, which was organized according to the “post office” model as a government department. The industries that were chosen for nationalization were not just key parts of the economy: they were sectors that were performing poorly and needed to be revitalized for the sake of the rest of the capitalist class. Once the Labour Party took power and began administering capitalist society, they became aligned with the perpetuation of that society. They came to power with a vision of using the state to promote the interests of the nation as a whole, and as a nation whose society was capitalist, that necessarily meant the interests of capital. Because they had to rely on state bureaucrats and capitalist methods of running the economy, economic “realities” like shortages due to the war and decolonization forced the government to operate “pragmatically” rather than risk social upheaval and a coup.

For comparison, consider the “dirigiste” policies of Charles de Gaulle in France. The “socialist” Attlee government was less able than the conservative de Gaulle government to nationalize and plan the economy because the latter deployed these measures against the development of socialism. Nationalization was done in the name of the nation and to the benefit of the capitalist class, which found that displacing parasitic monopolists in the banking, energy, and heavy industrial sectors greatly benefitted their bottom lines. Ultimately, Attlee’s nationalizations put him in the company of those of Bismarck, de Gaulle, Roosevelt, Mussolini, Park, and Disraeli—right-wing strongmen all.

Dramatic expansions of the public sector are far more correlated with the far right and nationalist center than they are with the left in a historical analysis. Significantly in the French case, when de Gaulle created his “dirigist” planned economy, there was no threat waiting in the wings of radical factions attempting to adopt the “co-operative” principle outlined by James Connolly:

state ownership and control is not necessarily Socialism – if it were, then the Army, the Navy, the Police, the Judges, the Gaolers, the Informers, and the Hangmen, all would all be Socialist functionaries, as they are State officials – but the ownership by the State of all the land and materials for labour, combined with the co-operative control by the workers of such land and materials, would be Socialism.17

Schemes of state and municipal ownership, if unaccompanied by this co-operative principle, are but schemes for the perfection of the mechanism of capitalist government-schemes to make the capitalist regime respectable and efficient for the purposes of the capitalist; in the second place they represent the class-conscious instinct of the businessman who feels that capitalist should not prey upon capitalist, while all may unite to prey upon the workers. The chief immediate sufferers from private ownership of railways, canals, and telephones are the middle-class shop-keeping element, and their resentment at the tariffs imposed is but the capitalist political expression of the old adage that “dog should not eat dog.”

By entering the capitalist state and relying on its institutions, such as the cops, the Labour government had already abandoned that principle, unbeknownst either to them or to their enemies.

One might be especially shocked to see post-coup Chile after the installation of Augusto Pinochet mirroring Labour’s expansion of the state sector. The coup to overthrow Allende had less to do with his policies of nationalization, although threatening American corporate assets gave the CIA impetus to back it, than it did with the threat posed by the socialist militias on the one hand, and the cybernetic economic planning apparatus the central government was organizing on the other. Pinochet never reversed the nationalization of copper, despite taking advice from the infamous “Chicago Boys” who introduced neoliberal policies to Latin America, and his regime maintained a highly interventionist state. Pinochet did allow his cronies and allies to rake in economic rents by “privatizing” the provision of many public services, but he also dramatically increased the level of central state control over them. Even when Pinochet privatized industries like steel, these industries were handed to loyalists and acted as an extension of the state, following central direction more closely than when they were “publicly-owned.” Pinochet may have been brought to power in part by those capitalists resentful of Allende’s seizure of their property, but his purpose was to prevent a transition to a socialist society, not to correct the balance sheet of public vs private ownership.

Just as the expansion of the public sector can benefit the capitalist class as a whole, the privatization of sections of the state can benefit the state as an institution. Removing control of transportation from local assemblies in Chile allowed the central government to more intensely regulate and shape transportation policy, just as the contemporary push for charter schools allows state bureaucrats to set curricula according to their real priorities; impose mechanisms like standardized testing in conjunction with capitalists; avoid the limited and flawed democratic input of local school boards; and get rid of unions altogether. In the case of the United States allowing religious charter schools, the state in regions controlled by Christian Dominionists are able to realize the true policy goals in spite of the secular democratic rights. Charter schools are just as much an extension of the state as public schools, despite the change in legal property form.

Whether something is part of the state is not determined by whether property is public or private. In a feudal monarchy, for instance, the state is the privately held property of the sovereign, while in a republic or a constitutional monarchy it’s allegedly owned by the whole people. Because they’re controlled by private interests, the curricula will mirror the ideologies those interests seek to promote. Likewise, privatizing prisons—in addition to creating a layer of parasitic rentiers siphoning off public money—makes those prisons no less a part of the state than if they were publicly-owned. Public prisons—just like private prisons—employ slave labor, strictly regulate the lives of inmates, and create institutional pressure to expand incarceration rates. While private prisons create contracts which allow them financial indemnities if the state fails to bring them up to sufficient capacity, public prisons lobby to increase incarceration through prison guard “unions” and informal pressures to justify padded budgets.

Does it matter if the secret police surveil you through publicly-owned means or through a privately-owned social media company? Does it make a difference to the working class if the occupation of Afghanistan is run more by the publicly-owned military or by mercenaries like Blackwater? Either way, war crimes are committed, contractors are made rich, and the American empire expands. By keeping the military a public institution, defense contractors can more easily siphon off government pork; but if that were to change, then the legal property form the military takes would change. The only difference between state and private institutions is which sections of the ruling class get to benefit from the institutional reproduction of capitalism.

What Kind of Demands?

Instead of building capacity to lobby the existing power of the state, socialists need to build their own power. No matter how many people we mobilize for protests, how well-crafted our transitional demands are, or how progressive our political candidates are, we are pleading with the mercenaries of the capitalist class to enforce our will.

This does not mean that there are no reforms that are worth demanding. It may sometimes be tactically viable to reduce the power of the capitalists using the regulatory force of the state: fining capitalists for dumping toxic waste, for emitting greenhouse gasses, banning discriminatory lending or renting practices. Reducing the freedom of capital to dominate our world is just as important as the overall reduction of the ability of the state to do so. Especially important are demands for the reduction of the powers of the state: the demilitarization of police, the abolition of regressive taxes, ending de facto segregation, respect for indigenous sovereignty, etc.

However, while demands on the state to constrain the rapaciousness of capitalism and check its own power are necessary and important, it is far more necessary and important to build our own power to force capitalists to capitulate without relying on the state. Getting the United States to end its massive financial subsidies to Israel for its apartheid-style occupation of Palestine would be good, but much better would be unions effectively blocking the shipment of goods to and from Israel—like the Longshoremen did on the West Coast against the South African apartheid regime. Instead of using the city government to zone in affordable housing, organizing mass rent strikes and using direct action to drive out developers would more effectively grow our power. When socialists try to use municipalities to accomplish these tasks, they only end up allowing their leadership to be co-opted: in the case of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, election of their leader Chokwe Lumumba to mayor of Jackson, MI led not to the “most radical [city] on the planet,” but his ‘revolutionary politics’ devolving into a “tough on crime” stance and publicly supporting the police through their civilian murders under his watch. Even if he were to improve the lives of Jacksonians—something many liberal and conservative politicians can claim they’ve done—Lumumba is complicit in the occupation of working-class communities by the mercenaries of the capitalist class.

Often cited as key “socialist victories” are public schools and public healthcare, but neither of these were created by socialists to embolden the working class. They were invented by right-wing nationalists such as Otto von Bismarck for the expressed purpose of undermining the autonomous power of the working class, ameliorating social dissent, and creating loyalty to the state from the general public. Even in countries where “progressives” pushed forward public education, it was based on the Prussian model and appealed to nationalist sentiment. To be sure, these institutions are not wholly reactionary: they provide valuable and essential services for social reproduction. In all societies which have organized social production, there is a need for institutionalized education and healthcare. Likewise, incarceration and social punishment are essential for the reproduction of class societies.

Crude analogies to prisons are not effective at teasing out what reactionary roles are played by welfare state institutions like public education and public healthcare. Unlike prisons, whose primary purpose is the disciplining of members of society into obedience to the class system, education’s primary purpose is the technical reproduction of society and therefore its class character is secondary. Aristotle was taught to the children of Greek aristocrats, feudal lords, and the capitalists all the same, but literacy and arithmetic have become necessary for a much wider mass of people than in previous modes of production. As Nikolai Bukharin said in The ABC’s of Communism:

the higher and middle schools teach the children of the capitalists all the data that are requisite for the maintenance of bourgeois society and the whole system of capitalist exploitation. If any of the children of the workers, happening to be exceptionally gifted, should find their way into the higher schools, in the great majority of instances the bourgeois scholastic apparatus will serve as a means of detaching them from their own class kin, and will inoculate them with bourgeois ideology, so that in the long run the genius of these scions of the working class will be turned to account for the oppression of the workers.18

Yet public education also serves the needs of the ruling class beyond the development of the technical capacity of society by playing an integral role in socializing workers for capitalist society. The schools, particularly in the social sciences, perform their secondary task by perpetuating the foundational myths of the American civic cult and are designed to make workers prepared for the “real” (capitalist) world. As Bukharin further argued:

In the elementary schools of the capitalist régime, instruction is given in accordance with a definite programme perfectly adapted for the breaking-in of the pupils to the capitalist system. All the textbooks are written in an appropriate spirit. The whole of bourgeois literature subserves the same end, for it is written by persons who look upon the bourgeois social order as natural, perdurable, and the best of all possible régimes. In this way the scholars are imperceptibly stuffed with bourgeois ideology; they are infected with enthusiasm for all bourgeois virtues; they are inspired with esteem for wealth, renown, titles and order; they aspire to get on in the world, they long for personal comfort, and so on. The work of bourgeois educationists is completed by the servants of the church with their religious instruction.19

This does not mean that compulsory free education is a bad thing—far from it—but it is important to consider the implications of who has power in any proposed education system. By many accounts, Catholic education is of a far superior caliber than the public education of many nations—for example, in the US where over 19% of working-age adults cannot even read a newspaper. Does this mean we should demand the schools of our children be transferred over to the Catholics? If we take the line that our demands should be for the most possible benefit for workers, it would seem so. A liberal secularist or a government socialist could object that public ownership of education makes for a more neutral curriculum than church ownership. However, as anyone who has been through a US History course in a public school knows, this is not true.

Just because state management of education is no better than church education does not mean socialists should support privatization or “charter schools”: privatizing the state does not change the character of state institutions. Instead, our demands should be for transforming schools into institutions run by teachers and staff, with state involvement limited to enforcing basic standards of quality. While the state cannot be trusted to develop curricula—look at the disaster that is Common Core—it can be used to prevent reactionary groups like creationists from poisoning impressionable minds with outright falsehoods. Workers’ parties can make an important difference in how these standards are determined; unless we struggle over certification requirements, the forces of reaction can shape them to their liking. Funding for many schools without a local tax base may require state subsidies, but alternatives like bussing or combining districts so local taxes are more evenly distributed are preferable.

More important than any demand on the state is for socialists to create their own independent schools. That does not mean abandoning existing public schools or sitting idly by while cuts are made to teachers’ salaries, just that we should push for them to be reorganized on the models we create independent of the state. Creating socialist homeschool networks, Montessori schools, and similar institutions is vital if we want to give the next generation of the working class a fighting chance to understand and remake this world. Coordinating these efforts is crucial: parent-educators, state-certified socialist teachers, and socialist theoreticians all have much to teach one another and require a unified effort to effectively do so. A serious and coordinated push for working class education that develops cadres of skilled proletarian educators prepares the type of infrastructure and knowledge needed for education in socialism. There may be differences between how the proletariat—now as a revolutionary class, later as the citizens of a socialist commonwealth—need to be educated, but the basic skills of radical pedagogy remain the same.

Like state education, state-run healthcare is a demand uncritically promoted by government socialists. But as Sophia Burns argues in her essay “The Socialist Case Against Medicare For All”, the state often plays a reactionary role in healthcare. The current medical industry promotes an ideology of health that is based around finding the most cost-effective and easiest treatments for any given ailment. Instead of looking at community-driven solutions, a mixture of personal responsibility and deference to professionals is cultivated. Instead of preventative solutions that focus on developing wellness both psychological and physical, health is the absence of diseases that might impede one’s ability to work. And—where a profit can be made— “health experts” promote an idea of fitness which is intended to police those who do not fit into conventional beauty standards: for example, research shows that a higher than recommended Body Mass Index is correlated with health, despite obesity being correlated with negative health outcomes. The medical industry has little interest in parsing health from patriarchy, capitalism, and racism. This does not mean that medications are bad or “big pharma” is the problem—many medications, particularly psychiatric medications, are lifesaving. But insurance companies tend to favor short-term solutions like cognitive-behavioral therapy or medicating away symptoms when relatively costly options like long-term therapies and environmental adjustments would likely prove more effective. This medical ideology is present in both public healthcare systems like the UK’s National Health Service, and private healthcare systems like those in the US.

Universal healthcare under existing laws would mean involuntary medical treatment for elders and the mentally ill gets dramatically expanded. It was not that long ago that hundreds of thousands of people were confined to psychiatric hospitals, and many of them were victims of serious medical abuse. It is not scaremongering or making a slippery slope argument that this could come back: involuntary treatment already exists for the autistic children of parents who can afford “Applied Behavioral Analysis” and for millions of elders whose insurance pays for their confinement. Many patients with dementia are locked in rooms and force-fed without any access to personal effects which might allow them to live a life with more dignity. Deinstitutionalization is frequently decried in publications like the Public Broadcasting Service’s Frontline where the argument goes that it is untreated mental illness that is the source of extreme poverty and victimization by police; but in reality it’s poverty and capitalism that force mentally ill people into the street, not a lack of public control of their bodies.

This control and abuse aren’t limited to the mentally ill and elderly. In Sweden—that bastion of “socialist” welfare—transgender people faced compulsory sterilization until 2013 . Likewise, in the UK, the NHS is alleged to treat transgender patients as “second class citizens”. This isn’t some aberration: public healthcare is based on the same capitalist, racist, homophobic, and transphobic structures as private healthcare. It was the United States Public Health Service, not private healthcare firms, which conducted the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Why should we trust the US government, whose agencies have been documented experimenting on its own citizens multiple times and violating its own Constitution, to administer our health? Is the American state of Donald Trump so much more enlightened and beneficent than that of the past? Any national health service in the USA will serve the interests of capitalism and empire, not those of the working class and oppressed people. Medicare for All may not expand the reach of the US government directly into hospitals, but is there any reason to believe that private corporations are any more ethical? Is having the government pay for your care at a monopolistic Catholic hospital chain which refuses to perform abortions and actively discriminates against transgender and gay people really something socialists should strive for? And would creating a true NHS style system in America really be advisable when groups like Evangelical Dominionists, Church of Latter Day Saints, and the Roman Catholic Church have enormous social influence and will have a say in public policy through conservative politicians?

Instead of focusing on expanding an institution designed to produce fit workers and meet the needs of capitalism, socialists must create alternative healthcare institutions. Creating worker-owned mutual insurance that has its policies consciously shaped by principles like reproductive justice, antiracism, and patient autonomy is a necessary task of our movement. However, the height of our immediate ambition should not be limited to mutual insurance: we should strive to set up free clinics, therapy groups, wellness clubs, and other infrastructure that is organized to both meet the needs of workers and empower them. Socialism isn’t just winning more quantitative gain or social surplus—it’s the working class self-consciously improving society in a qualitative way.

Moreover, whether or not universal healthcare passes is not something socialists will have any meaningful impact on. Government socialists have no federal representatives, author no legislation, and are merely one “interest group” that left-wing Democrats allow. Even if Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez wins the general election, her lone vote will have little effect on government policy. The Democrats will do what is necessary for their party to effectively serve the section of the capitalist class that they represent.

It’s possible that in the course of the class struggle struggle, the Democrats will pass Medicare for All or even a nationalized health system—and either one could mean that the accomplishments of socialists in creating mutual insurance or providing healthcare would evaporate. But that does not mean that building them is for nothing: creating worker-run insurance and clinics would build up any necessary administrative and technical skills among socialist militants. It would also have made a serious difference in the lives of many workers and served as a proof-in-concept of a different model of healthcare for revolutionaries to look to besides the one that predominates under capitalism. Not only that, but it would serve as a stark example for workers that the state’s interests are inherently opposed to the freedom and needs of the working class. Were the Socialist movement to have built alternative institutions, creating an American NHS would mean the state would be taking away care, not expanding it.

Some socialists might object to opposing Medicare for All or even Obamacare on the basis that these programs have saved and would save lives. As things stand, socialists have no influence on what the government does: Obamacare was created with zero input from socialists and it was in the interests of capitalism to establish it. A balloon in insurance prices was creating economic instability and the capitalist class had to address it. That it saved many lives—the author’s included—is a happy side effect, not the real aim of the policy. Were a socialist movement opposed to Obamacare or Medicare for All to have the power to stop it, that same movement would have the power to create a much more humane and comprehensive alternative. The choice isn’t to support public healthcare or support private healthcare—and even if it were, calling on socialists to build alternatives in no way undermines the ability of the capitalist class to solve the contradictions of its economy with public healthcare.

Magnetic Program

So, if revolutionary socialists shouldn’t make demands for the expansion of the state like Medicare for All and expanded public schools, then what should our demands look like? What kind of program should we use? In the early socialist movement the minimum-maximum program—which began as a method of articulating the aims of revolutionary workers—left too much room for government socialists to promote their anti-class-independence lines within the workers’ parties and thereby facilitated their degeneration into reformism. The program allowed those who had already capitulated in deed to remain revolutionaries in word for a time, thus allowing them to mislead the militant sections of the working class into continuing to support them in the name of unity. Instead, a new type of program must be developed that doesn’t allow for government socialism to be hidden inside.

The most important part of a revolutionary program is that it does not include any demands which constitute a positive relationship with government power. Instead, demands of the state should be purely negative in relationship to either it or towards capitalism’s control of the working class. This is the negative—or destructive—program. Demands of the negative program would include regulations like environmental or workplace safety protections, freedom of the press, lower taxes on the working class, and equal pay between the sexes and races. State regulations are not acceptable as demands—only as concessions. Having the state hold a corporation accountable for environmental degradation does not build our power—only building working-class institutions does that— but it does shift the resources of the state towards ends that are not harmful towards our movement. By limiting the negative program to a curtailing of state and capitalist power, there is no room for government socialist solutions like nationalization or state provision to hide.

The tasks of the working class that lie beyond the state also need clear articulation. To supplement the negative program, there is the positive program. The positive program is defined by the constructive aspects of the socialist movement; it lays out what the workers’ movement seeks to build and what it needs independent of the state. This program makes no demands of the state because the institutions it seeks to build are only valuable when as they’re independent from the state—run by and for the working class. Planks of the positive program would include the organization of red unions, mutual insurance, free clinics, firearm education for workers, free childcare, tenants unions, worker-managed cooperatives, community self-defense organizations, new forms of education, and other programs and institutions that emerge organically from the struggle of the working class. The positive program should include both minimum aims and the maximum aims of socialism: our minimum aims are things we can build right now while our maximum aims are the things we need socialism to organize. By linking the two together, it emphasizes the continuity between revolutionary action in the near term and the ultimate aim of the establishment of working class rule in society. The kinds of institutions envisioned by the positive program are collective and participatory-democratic in nature, and are therefore necessary for revolutionary socialist “base-building”.

All movements that seek to gain institutional power base-build, including the Democratic Party: it uses grassroots fights and low level mutual aid to build political machines through progressive churches, yellow labor unions, and reformist socialist groups like the Democratic Socialists of America. The aim of the extended Democratic Party cadre which run these organizations is to cultivate an electorate which can be mobilized to advance the interests both of sections of the Democratic Party and of the Party as a whole. While some forms of base-building experimented with by the government socialists—which includes all existing electoral Socialist parties—and the Democratic Party do promote a feeling of empowerment, those that tend to stick all require passive participation by the majority of those involved rather than active participation: canvassing operations, yellow unions, and electoral organizations.

Conversely, revolutionary socialist base-building requires the active and collective participation of as many involved as possible. Revolutionary socialist base-building strives towards the end of the division of labor while recognizing that it exists and works to develop leadership among all of the oppressed and exploited in society. These institutions aren’t so outlandish or inconceivable as some government socialists would have you believe: the working class built them in the 19th and 20th centuries under much worse conditions than we face today. The false concern by some “socialists” about the ability of workers to fund these kinds of institutions is undermined by their lauding the Sanders campaign for raising so many small donations and promoting hugely expensive electoral projects as viable. If political campaigns in conditions of a weakened socialist movement are able to be funded by small donations, why can’t independent institutions? And for that matter, if unions can be self-funded with dues, why couldn’t mutual insurance or a housing cooperative? The failure of government socialists to imagine creating these kinds of institutions is a result of their lack of faith in the very working class they believe could somehow run society. How do they expect the working class to rule society without training to do so? The truth is, of course, they don’t: they think that they should run society on behalf of the workers.

Like a magnet, a revolutionary program has two poles: positive and negative. The positive pole will bind together the critical mass of self-conscious workers needed to overthrow the existing order. Inversely and jointly, the negative pole repels reformism and opportunistic alliances. By putting this magnetic program it into practice, a workers party will be able to generate the power necessary to put the engine of production into the hands of our class.

The magnetic program is not necessarily abstentionist or incompatible with running candidates. If a candidate stood on a platform of obstructionism and a reduction of state power, while also acting as a “tribune of the people” in the halls of government, they would be a candidate who revolutionary socialists might support. The slogan of revolutionary socialists in parliaments and Congress is “Not One Penny, Not One Life” for capitalist wars and the preservation of the bourgeois order. The work of revolutionary socialist parliamentarians is to grind the functioning of the state to a halt and make room for workers’ institutions to fill in the emerging gaps. Whether or not it makes sense to invest time and energy into running candidates in favor of other forms of organizing is a tactical problem and not a strategic one. It may be that a group using the magnetic strategy never sees a need to contest an election as it fights in the class war, or it might be the case that it contests every election it can with the aim of liquidating municipal and regional governments into worker-controlled institutions. But either way, the relationship between the organization and the state remains the same.

This framework of organizing is not “anti-welfare.” It is against policies like “means testing” and the existence of expansive state bureaucracies for the doling out of the working class’s own surplus product. Even if proposed welfare doesn’t include means testing, though, creating government services that are free at the point of use requires an expansion of the state sector funded by the surplus product of the working class. While this may be controversial, rather than defend the welfare state as a whole, revolutionary socialists should fully embrace the calls for a universal and unconditional income. In isolation, a Universal Basic Income is not revolutionary—it does nothing to elevate workers out of the conditions that they’re in. But coupled with the creation of working-class institutions—which a UBI would free many workers up to staff—a UBI could serve as a real “social wage” returned to the class in exchange for the invisible labor and unwaged labor done by all people to reproduce capitalism. Programs which are free at the point of use are important, but they should be created of, by, and for the working class—not the state. Now, a UBI which is solely based on citizenship would certainly create welfare chauvinism not unlike what exists in Europe today around public services, so any proposed UBI from revolutionary socialists would have to include undocumented workers. Our goal is not to create a caste system and a Roman-style proletariat of exploiters, but to expand the capacity of the working class to fight the class war.

Government socialism is a dead end that will only end up co-opting those parts of the socialist movement that embrace it. The state isn’t neutral and its interests are inherently opposed to ours if we want to create a new society. If Marxists are to organize in a revolutionary socialist way, we need to embrace a negative relationship with the state while organizing a revolutionary base. Many who call themselves Leninists, Marxists, democratic socialists, or even anarchists might balk at the proposals laid out here, but opportunism knows no distinction between tendency. The magnetic program is no panacea; it is merely one possible rubric for revolutionary socialists to apply to their organizing for the overthrow of the capitalist system and the establishment of the rule of the working class. But if we allow our resolve to be weakened and make false unity with the government socialists as did classical social democracy, history will repeat itself as farce. Instead, through principled struggle we can build the Co-operative Commonwealth together.

- Mao Zedong, “Problems of War and Strategy”, Selected Works, Vol. II (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1938) p. 224.

- Frederick S. Boyd, “The General Strike in the Silk Industry,” in The Pageant of the Paterson Strike (New York: The Success Press, 1913), p. 5.

- Saul Alinsky, “Tactics,” in Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals (New York: Vintage eBooks, 2010), p. 127.

- Leon Trotsky, “Why Marxists Oppose Individual Terrorism” (1911).

- Engels, ‘A Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Programme of 1891″, in MECW Vol. 24, (Moscow: Progress Publishers 1975) p. 340.

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Critique of the Gotha Programme (London: Progress Publishers, 1970)

- Frederick Engels,”Letter to Bernstein in Zurich (1882)”, Marx-Engels Collected Works Vol. 46, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975) p. 353

- Frederick Engels, “A Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Program of 1891”, MECW Vol. 27, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975) p. 217

- Lassaleanism was a rival socialist movement to Marxism that promoted ideas like state-funded cooperatives, state-run health insurance, and an alliance between the working class and the aristocracy against the bourgeoisie

- Leon Trotsky, The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International: The Mobilization of the Masses Around Transitional Demands to Prepare the Conquest of Power : the Transitional Program (New York: Labor Publications, 1981)

- Ibid.

- A prominent Socialist Alternative party member

- See: The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939–1949 by Victor G. Devinatz

- Lenin, Vladimir Ilʹich. State and Revolution: Marxist Teaching about the Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution. (New York: International Publishers, 1935.) p. 7.

- Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy (New York: Free Press, 2008), p. 27.

- Ibid.

- James Connolly, “State Monopoly vs Socialism,” The New Evangel, June 10, 1899

- Nikolai Bukharin and Evgenii Preobrazhensky, “Chapter 10: Communism and Education,” in The ABC of Communism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969).

- Ibid.

41 Replies to “Where Does Power Come From?”

Comments are closed.