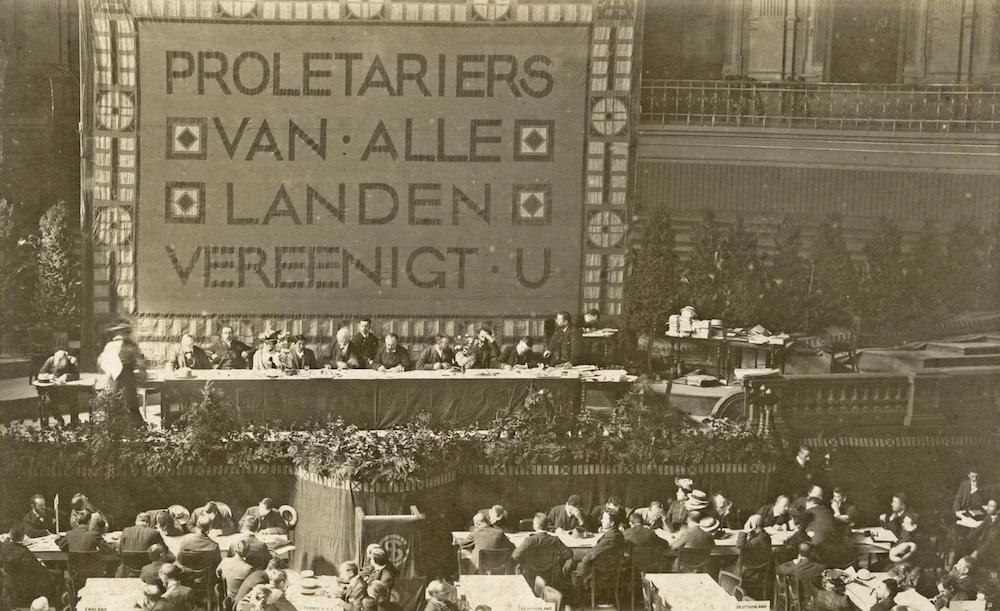

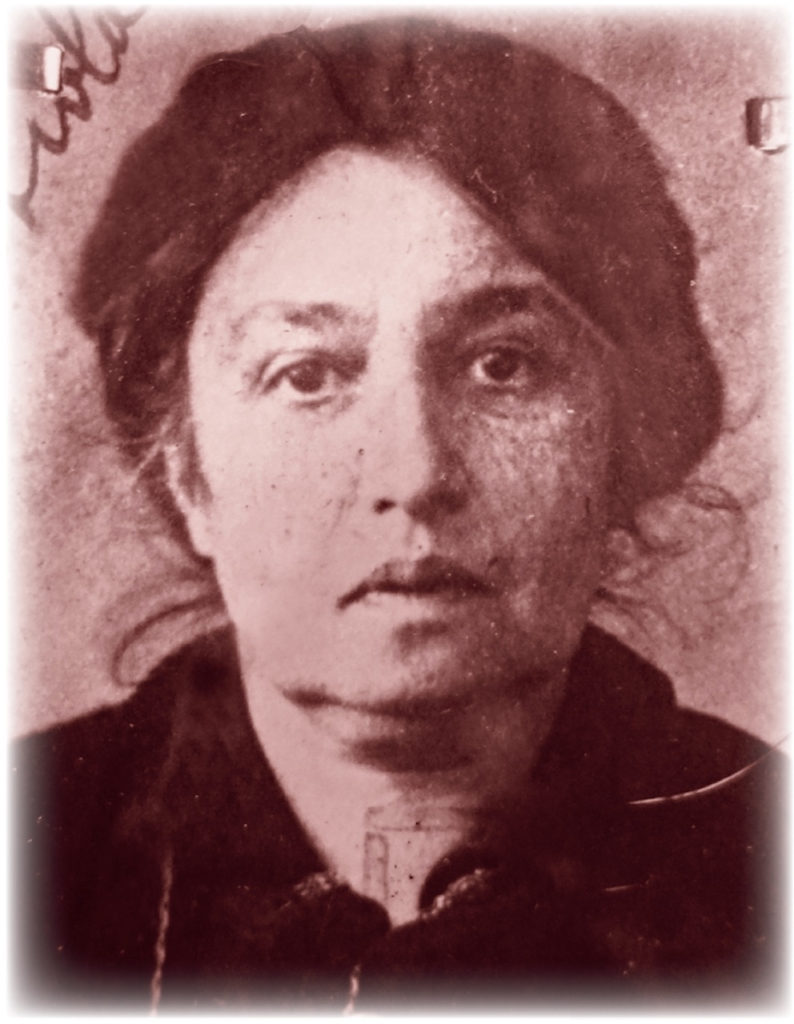

In honor of International Women’s Day, we publish this translation by Ben Klein of a historic document of the socialist women’s movement. What follows is a report on the Second International Socialist Congress of Women that was held in Copenhagen in 1910. The report was originally published in Clara Zetkin’s Die Gleicheit, the fortnightly magazine of the SPD’s women’s movement. To support Ben’s work translating similar documents become a patron of Marxism Translated.

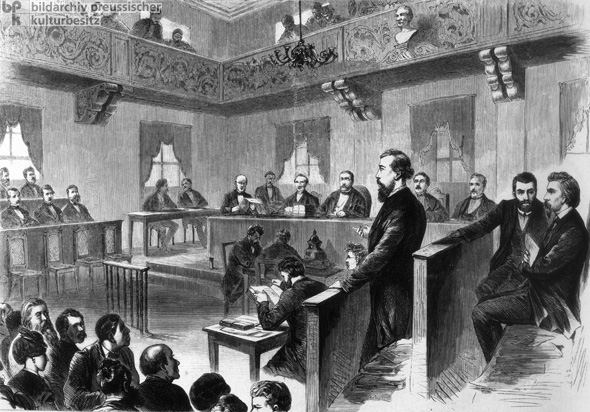

The Second International Socialist Congress of Women in Copenhagen (1910)

First published in Die Gleichheit, 25 (1910), pp. 387-390

The significance of the Second International Conference of Women Socialists should not be judged by its depiction in the press. There it was overshadowed by the larger, more significant event that proceeded it – the International Socialist Congress – to such an extent that the essential features and significance of the women’s conference could not be clearly outlined. Its importance and its achievements, however, will undoubtedly find expression in the activity of the women comrades of all countries who sent their representatives to the meeting. And this is what matters. If we examine the outcome of the proceedings in Copenhagen from this perspective, then the female comrades ought to be satisfied with it. The conference broadened and strengthened the relations between the socialist women of the various countries and here and there increased the common understanding of the central features of the movement. For some it shed clear light on the fundamental socialist attitude on many an important question, while for others it led to new fruitful suggestions for practice. So it was that nobody went home from the meetings empty-handed, and those who had things to offer in one respect benefited in the other. The appreciative and uplifting awareness of this interaction can only help to strengthen the bonds which unite the female comrades of all countries in their will to work as uniformly as possible in the service of the shared great goal of socialism.

If the necessity of international coordination between socialist women had not yet been established, then the Copenhagen Conference did so not only by its sizeable attendance, which speaks of a vividly felt need for such discussions but also, and above all, by the course of the negotiations themselves. Delegates were present from seventeen different nations and it is both understandable and extremely gratifying that the Danish and Swedish women comrades sent a particularly strong delegation. We may hope that from now on the women comrades in the Scandinavian countries, whose work exhibits both so much freshness and a deep yet controlled enthusiasm, will have established close contact with the Socialist Women’s International. The same is true of the American women comrades, but it will take time for an organized socialist women’s movement to develop in the Romance-speaking countries that will seek connections with the sister movements abroad.

There are many signs that our hopes for this are certainly justified. The trade association of seamstresses and shopfitters in Lisbon wanted to express its solidarity with the comrades at the congress and its desire for constant contact with them, so it gave comrade [Clara] Zetkin a mandate. In the Italian Socialist Party, there is a growing recognition that the women of the working people must be trained in socialism and united in an organization. A discussion of the woman question at the forthcoming party congress is to set in motion the related systematic work and draw up guidelines for it. The Executive Committee of our fraternal party in Italy, therefore, sent comrade [Angelika] Balabanoff to the conference as a delegate and conveyed its heartfelt congratulations for the work of the congress, which unfortunately arrived too late to be read out. The same happened to two other letters: one from comrade Tillmann, who wrote on behalf of the National Association of Socialist Women in Belgium, and another from a recently founded socialist women’s group in Lille (North France). We are convinced that the beginnings of the unified activity of the female comrades in the Romance countries will be fostered by these international links. The next International Socialist Women’s Conference will therefore no longer exhibit the gaps and shortcomings that we are so painfully aware of at the moment.

During the discussions on the means of making international relations between the women comrades of all countries more regular and firmer, there were many proposals and suggestions for things that already exist, such as the international exchange of socialist women’s publications, the submission of correspondence to a central office for further dissemination and so on. Of course, such proposals came from women comrades who had only recently, or almost never, come into contact with the International Secretariat. Much more ambitious was the proposal of our female comrades from the Netherlands to establish an international women’s journal that would not only provide information about the state of the socialist women’s movement in the individual countries but would also deal with emerging problems of the woman question from a socialist point of view, taking into account everything that relates to that question. The comrades justified this demand in particular with reference to the urgent need to train women comrades in the fundamentals and to the inadequate treatment of the various aspects of the woman question in the socialist press. The Dutch comrades withdrew the motion after comrade [Luise] Zietz had convincingly shown both the practical impossibility of its realization and that this need should be addressed in another way. Through their correspondence, she said, the comrades of the different countries should bring their desire for a theoretical discussion of individual questions to the attention of the international secretary, who would then see to it that they were dealt with in Die Gleichheit. Comrade Zietz rightly pointed out that the articles in question would be useful not only to female comrades abroad but also to newly recruited women. Her suggestion met with general approval, since – as was stressed by all sides – Die Gleichheit has certainly proved its worth as a central agency and publication for international correspondence.

Without doubt, the highlight of the conference was the discussion on female suffrage. Once again, it became apparent how, as soon as major questions of principle are fought over, the debates acquire inner substance, strength, and momentum. And that was the case here too. Those comrades present who were familiar with the situation and knew that a not inconsiderable number of leading English female comrades – despite all of the resolutions passed by the trade union and party congresses in their own country and the International Socialist Congress in 1907 – unfortunately were fighting alongside bourgeois women’s rights activists for a restricted women’s suffrage; for those comrades familiar with this situation, it was clear from the outset that the discussions would revolve not around the question of the means but the goal itself. And so it came to pass. The well-represented English comrades, who belong to the Independent Labour Party and the Fabian Society, warmly advocated that the passage that characterized the restricted right of women to vote in a sharp and principled manner should be deleted from the resolution proclaiming the struggle for universal suffrage for all adults. This characterization, they argued, was an indirect condemnation of the attitude of those comrades who had initially supported the demand for a restricted right to vote for women in England.

The comrades Murphy, Butcher, Philipps and others tried in vain to justify this position. Their reasoning is well-known: the nature and the effects of a restricted suffrage are not as bad as they appear in principle, they said; it could of course not the be the overall goal of the struggle for the political emancipation of the female sex, but represented an important in that direction; in England they had to take what could be achieved at this moment in time and so on. The fact that this reasoning was repeated on several occasions did not exactly bolster its cogency. Nor did it become more convincing by the fact that it was combined with a glorification of the good hearts and minds of the bourgeois ladies, as well as of the advantages that could be gained from working hand-in-hand with women’s rightism/feminism [Frauenrechtlerei]: in short, this reasoning lacked a correct understanding of the significance of class contradictions.

It also completely undermined the impact of the speech by Mrs. Charlotte Despard, one of the most passionate and energetic leaders of the Suffragettes, in which she defended a restricted franchise for women. To be sure, all delegates were unanimous in holding this distinguished old woman, and the civic virtues she has practiced, in the highest esteem. However, the overwhelming majority of them were just as united in regretting that such great, beautiful qualities were being wasted on such a petty and unfortunate matter as restricted female suffrage. The delegates responded with a virtually unanimous, unflinching ‘no” to the proposal to advocate universal suffrage without a corresponding denunciation of restricted female suffrage. The resolution was adopted with 10 votes against, which were cast by a section of the English delegation. Led by comrade Montefiore, the commendable champion of suffrage for all adults, a minority of that delegation sharply criticized the tactic of compromise. The debate that preceded the vote was a vivid demonstration of how fruitful the Stuttgart conference had been, and how much clarity and consolidation the international socialist women’s movement owes to its work. It was a pleasure to listen to the speeches by comrades Twining and May Wood-Simons from the United States, comrades Dahlström and Gustafson from Sweden, comrade Gjöstein from Norway, comrade Kollontai from Russia, comrades Zietz and Popp from Germany and Austria respectively, comrades Montefiore, Grundy and Burrows from England. In each speech there was the same basic tone but no tiring repetition, because in each address the clear grasp of principles was supported by valuable factual material which outlined the character and the effects of restricted female suffrage and the role of class antagonisms in the world of women [Frauenwelt]. The statements made by our American comrades deserve special mention in this context. They outlined a splendid refutation of the fondly told fairy tale of the sisterhood of the female sex, of the fairy tale of the bourgeois women’s movement showing sympathy for proletarian interests wherever that movement is in bloom and its political demands have been fulfilled. It should be noted that the German comrades’ resolution on the question of women’s suffrage was improved by two amendments from the Austrian comrades. They prevent any misunderstanding of our demand by expressly calling for women’s suffrage in the individual federal states or Crown lands, and call for the right of women to stand for all legislative and administrative bodies. The proposals on how to develop the most uniform practical work possible for the introduction of women’s suffrage found unanimous approval. Now it is up to the female comrades of all countries to put the resolutions into practice. This particularly applies to the decision to deploy a new means of agitation in the form of ‘Women’s Day’: we use this means without any illusions. We know that it does not mean the world for the conquest of political rights for women, but we also have a firm will to give it the practical scope that a well-prepared Women’s Day can have and must eventually gain.

The Women’s Conference was not spared the loss of concentration and freshness which, as experience shows, tends to follow major debates of matters of principle at all conferences. We regret that the treatment of the questions of social childcare and schools suffered as a result. The discussion of these issues also suffered from other factors, such as the lack of time and the discussion of a matter that had not been foreseen, namely the prohibition of night work for women. As a result, maternity and child care could not be dealt with in the breadth or depth that the range of the conditions and demands for reform deserved. Comrade Duncker, who spoke to the resolution of the German women comrades, gave a concise but incisive presentation on this subject, which, together with the speech of comrades Nielsen (Denmark) and Pärsinnei (Finland), highlighted just how many factual insights we would have gained from further discussion. The debate concluded with the adoption of a resolution from the German comrades and a motion from England, which outlined the general principle that society is obliged to care for mother and child. In our opinion, this does not settle this important question once and for all for the female comrades from the various countries. Some of its aspects will need to be dealt with on another occasion; we are thinking in particular of the important social measures to benefit school-age children that are not being provided for. The conference also referred two motions from our Finnish comrades on the position of mothers who have given birth out of wedlock and the punishment for infanticide to the next conference.

The fact that a socialist women’s conference could be called upon to oppose banning night work for women was a painful surprise to some comrades. This demand was passionately supported by the large majority of Danish and Swedish delegates and is characteristic of the fact that the movement in these countries has not shed either the influence of feminist views nor the narrow ties of an egotistical guild-professional evaluation of things. It was the feminist platitude of the “woman’s right to work”, of the mechanical “equality of the sexes”, it was considerations that only took into account the circumstances of the small group of women typesetters that led to the demand: “No ban on night work for women”. Unfortunately, the majority of Swedish female comrades has already made it difficult for the Social Democratic Party there to advocate this urgently needed reform by organizing a protest action. In Denmark, the Social Democratic Party is similarly in the embarrassing position that a considerable number of women comrades are still fighting against the ban on female night work. In light of this situation, a confrontation on this contentious question, which is no longer an issue at all for the women comrades in any other country, became inevitable. At the eleventh hour, female comrades from Denmark put forward a motion opposing the ban on night work for women, which, according to the conference decision, had to be dealt with together with social welfare for mother and child. The protest against the ban came in particular from the Danish comrade Frone, a Social Democratic city councillor in Copenhagen, who spoke with emphatically and spiritedly and had the strong support of the great majority of Danish and Swedish delegates. Comrade Vang (Copenhagen) responded to this protest with a declaration in which she, as a member of the Social Democratic Party’s Executive Committee, briefly explained the opposite point of view held by the Danish Social Democrats and the minority of Danish delegates to the Women’s Conference. Comrade Hanna, the representative of the Women Workers’ Commission of the German trade unions, spoke convincingly against the motion. In the vote, all the nations represented came out against the motion, with the exception of the Danish and Swedish delegations, in which, however, there was also a minority against it. We hope that these discussions will help to support the educational work being conducted by this minority and lead the entirety of the Danish and Swedish women comrades to demand a ban on night work for women.

The Danish comrades had tabled a second motion to summon the social democratic parties of all countries to support vigorously the legal prohibition of domestic work [Heimarbeit]. However, they withdrew it after the German delegation had responded with a counter-motion calling for its legal regulation and restructuring. Two proposals from the League for the Interests of Working Women in England were approved in principle by the conference. One spoke in favor of state insurance for widows, the other in favor of measures to benefit unemployed women. The very different degrees of internal and external development of the women’s movement in the individual countries was expressed through numerous motions that demanded what has long existed and has become a matter of course, wherever female comrades are well organized with a clear awareness of their aims in their ranks. In order to promote the movement’s progress in those countries where this is not yet the case, the conference approved several such proposals in principle. They relate to agitation among the female proletariat, the training of female comrades, affiliations to the party and the trade unions, moral and material support for social democratic women’s publications and so on. Of greater importance was a resolution from the female comrades in Austria – moved effectively by comrade Freundlich – which sought to make the artificial rise in the price of the proletarian life the point of departure for systematic agitation that can enlighten women about the essence of the capitalist social order and lead them into joining the political organizations, the trade unions and the consumer associations in which the spirit of the modern workers’ movement is vibrant.

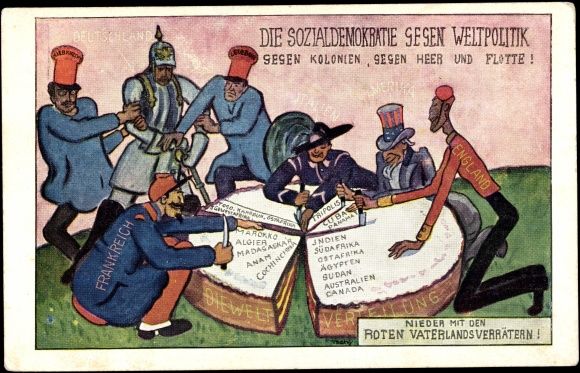

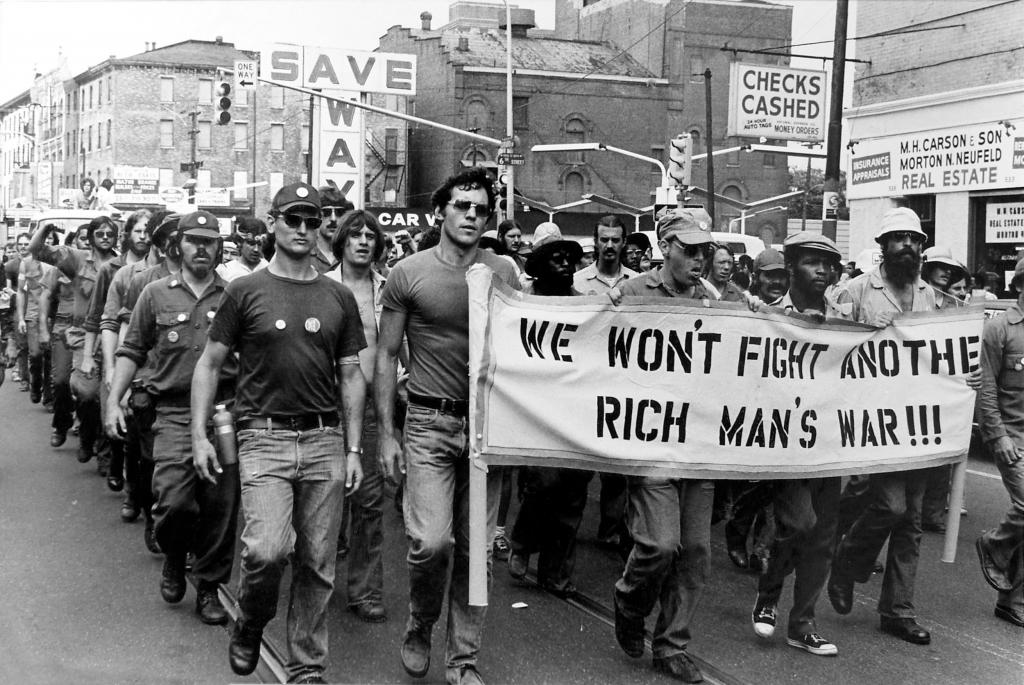

Two other conference decisions deserve special mention. Before starting its business, the conference agreed by acclamation a resolution tabled and moved by comrade Zetkin, which denounced Russian tsarism’s attack on Finland’s political freedom and expressed the deepest sympathy for the struggle of the Finnish people for their rights. Likewise, by acclamation, the conference agreed to the resolution from the German and Austrian delegations and the Socialist Women’s Bureau in England, which reminded the socialist women of all countries of their special task in the struggle against militarism and war: to educate the youth in socialist ideas and, through incessant agitation amongst the female proletariat, to strengthen the awareness of the power which women enjoy due to their role in economic life and which they can – and must – assert. With this resolution, the conference dealt with motions from Sweden and England that were in line with comrade Ihrer’s splendid remarks on the need to place the maintenance of peace on the conference agenda.

In conclusion, it should be noted that the conference was delighted to receive a letter from August Bebel, which we will publish elsewhere in this publication. The stormy applause with which the delegates met the letter and the proposal to send him the conference’s best of thanks and warmest wishes, was testament to the deep admiration which the female comrades of all countries have for this great champion of the rights of the female sex and of the liberation of the working class.

The International Women’s Secretariat will continue to exist in its current form. Comrade Zetkin was unanimously re-elected as its International Secretary. The Third International Women’s Conference will take place after the next International Socialist Congress, which will take place in 1913 in Vienna. In the future, a working committee of comrades from different countries will participate in the preparation and organization of the conferences, so that a preliminary meeting can be held in good time to make the arrangements for fruitful discussions. This decision, which the experience of the first two conferences has shown to be a practical necessity, is very much to be welcomed. Implementing it means avoiding the disturbances and grievances that made themselves uncomfortably felt at the second international conference. It will also relieve the secretary of additional organizational work, which is absolutely necessary. It would be easy to say a great deal about this deficiency, with which the conference was confronted and which all international meetings are likely to face and which, on top of everything else, occurs during the particularly difficult conditions of organizing the women’s conference. But it strikes us as more important to demonstrate the valuable work that has been done in Copenhagen. It will stimulate the further work of the female comrades in all countries, make it more uniform, clearer, and make it an increasingly valuable part of the proletarian struggle for emancipation. Our deepest thanks must go to the Danish comrades, as well as the political and trade union organizations behind them, who made the conference in Copenhagen both possible and successful, and who ensured that the hours of effort and work were enriched by infinitely amiable and warm hospitality, is due to our Danish comrades and the political and trade union organizations behind them. The young socialist women’s international has only one slogan: ‘Forwards!’