Matthew Strupp lays out the politics of revolutionary defeatism in contrast to the approaches of third-campism and third-worldism.

In April 1964, at a luxury hotel overlooking Lake Geneva, a young Jean Ziegler, at that time a communist militant, asked Che Guevara, for whom he was serving as chauffeur, if he could come to the Congo with him as a fighter in the commandante’s upcoming guerilla campaign. Che replied, pointing at the city of Geneva, “Here is the brain of the monster. Your fight is here.”1 Che Guevara, though certainly not a first-world chauvinist, recognized the crucial role communists in the imperialist countries would have to play if the global revolutionary movement were to be successful. How then, as communists in close proximity to the brain of the monster, or in its belly, as Che is reported to have put it on another occasion, can we effectively stand against the interests of “our” imperialist governments? The answer to that question is the policy of revolutionary defeatism. This article will go over the origins and meaning of defeatism, take a look at its complexities with the help of some examples, and take up the challenge posed to it by the politics of both third-worldism and third-campism.

Origins of Defeatism

The logic of revolutionary defeatism flows from the basic Marxist premise that the proletariat is an international class, and that in order to triumph on a global scale it needs to coordinate its political struggle internationally. This means that when workers in one country are faced with actions by “their” state that pose a threat to the working class of another country, they must be loyal to their comrades abroad rather than their masters at home. Rather than be content with simple condemnations, they must also pursue an active policy against their state’s ability to victimize the members of their class in the other country. This means strike actions in strategic industries, dissemination of defeatist propaganda in the armed forces, and organizing enlisted soldiers against their officers. In the case of a particularly unpopular or difficult war, all politics tends to be reoriented around the war question, and, if the state has been destabilized by the demands of the war and the ongoing defeatist activity of the workers’ movement, this can lead to an immediate struggle for power and the possibility of proletarian victory. If no such conditions are present, the defeatist policy can serve to train the proletariat and its political movement to oppose the predatory behavior of its state and, in practical terms, blunt the business-end of imperialism and mitigate its devastating consequences for the working class abroad.

This policy of defeatism developed alongside the growth of mass-working class politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the proletarian movement grew to the point where its international policy became a live and important question. There were many positions bandied about in this period, some more or less defeatist, others placing the workers’ movement squarely behind national defense. Many individual socialists, including Marx and Engels, varied in their advocacy of one or another. An early expression of a policy of revolutionary defeatism can be seen in Engels’ 1875 letter to August Bebel, in which he criticizes the newly drafted Gotha Unification Program of the German Social-Democratic Party (SPD) for downplaying the need for international unity of the workers’ movement. Engels writes:

“…the principle that the workers’ movement is an international one is, to all intents and purposes, utterly denied in respect of the present, and this by men who, for the space of five years and under the most difficult conditions, upheld that principle in the most laudable manner. The German workers’ position in the van of the European movement rests essentially on their genuinely international attitude during the war; no other proletariat would have behaved so well. And now this principle is to be denied by them at a moment when, everywhere abroad, workers are stressing it all the more by reason of the efforts made by governments to suppress every attempt at its practical application in an organisation! And what is left of the internationalism of the workers’ movement? The dim prospect — not even of subsequent co-operation among European workers with a view to their liberation — nay, but of a future ‘international brotherhood of peoples’ — of your Peace League bourgeois ‘United States of Europe’!”2

Engels is congratulating the German workers’ movement for their internationalist behavior in war but chiding them for retreating from this internationalism in their political program. The war he is referring to is the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Marx had actually initially been German defensist in this war but changed his position after German troops went on the offensive.3 The German workers’ movement as a whole, though, mostly opposed the war in an admirable fashion, and Engels claims this was the reason for their esteem in the international movement. Not only did its political leaders condemn the war, but its organizations also carried out strikes in vital war industries in the Rhineland. This active stance of opposition to the war and active coordination of international political activity by the working class is what Engels thought was missing from this part of the Gotha Program, and he thought it was a step down from the truly international perspective of the International Workingmens’ Association. Its drafters included the vague internationalist language of the “Peace League bourgeois”, but made no mention of the practical tasks of the movement in this respect. Engels argued that the workers’ movement needed to coordinate its activities on an international scale, and that included acting in an internationalist fashion during war-time.

Nor did Engels limit his expression of a precursor to revolutionary defeatism to wars within Europe, where there was a developed working-class movement that could be destroyed in another country by an invasion from one’s own. He thought it was also applicable in matters of “colonial policy”, and that workers in imperialist countries had the political task of organized opposition to imperialist exploitation. He believed that if they failed in this task they would become political accomplices of their bourgeoisie. In an 1858 letter to Marx he wrote:

“the English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois, so that the ultimate aim of this most bourgeois of all nations would appear to be the possession, alongside the bourgeoisie, of a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois proletariat. In the case of a nation which exploits the entire world this is, of course, justified to some extent.”4

These writings of Engels’ express two important features of Lenin’s revolutionary defeatist policy in World War I and that of the Communist International after the war. Namely, the importance of active, organized efforts to hamper the ability of one’s own state to carry out the business of war and imperialism, and the applicability of the policy to both inter-imperialist wars and to colonial and semi-colonial/predatory imperialist wars.

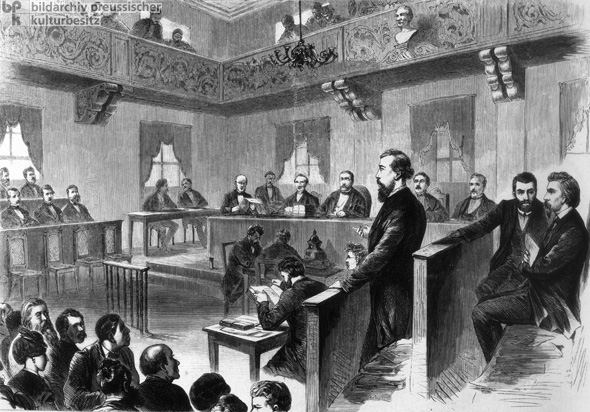

The Second Socialist International received the first major test of its ability to pursue a defeatist policy with the onset of World War One– and it failed spectacularly. Up until that point, the German SPD, the model party of the International, had followed an admirable policy of voting down all state budgets of the German Empire in the Reichstag under the slogan “For this system, not one man and not one penny!”, as Wilhelm Liebknecht declared at the foundation of the Bismarckian Reich.5 This policy allowed the German party to think of its parliamentary activity with a lens of radical opposition, through which they saw themselves as infiltrators in the enemy camp, intent on causing as much trouble for the state and its ability to rule as possible and securing whatever measures they could to benefit the movement outside the parliament. They made use of all the procedural stops they had at their disposal along the way, and used their parliamentary immunity to decry abuses like violence against the workers’ movement and German colonial wars in ways that would otherwise be illegal, though this didn’t keep August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknect, for many years the SPD’s two representatives in the Reichstag, from being convicted of treason and imprisoned for two years for their opposition to the Franco-Prussian War, particularly for linking opposition to German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to support for the Paris Commune.6 This was not a revolutionary defeatist policy in itself and the behavior of socialists in relation to the armed forces in wartime remained untheorized, but it was an important attitude for a party of revolutionaries to adopt towards their own state and its warfighting capacity. Politicians the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) has elected in the United States, unfortunately, do not seem to see their activity in the legislature in this way and seem to think they are there more to “get things done” than to “hold things up” for the benefit of the movement. The DSA has also failed to adopt a “not one penny” position on the military budget. A resolution to do so was introduced at the 2019 convention, but was not championed by either of the main factions there.

In August 1914 the SPD’s anti-militarist discipline broke down, as many of its representatives in the Reichstag voted for German war credits and much of the movement fell in line behind the war effort. The same happened in all the other parties of the International in the belligerent countries, with the exception of Russia and Serbia. The divide between those who supported the war and those who opposed it did not follow the existing pre-war political divisions. War socialists were drawn from the right, left, and center of the International. Some made the decision on the basis of “national defense” or out of an unwillingness to become unacceptable to bourgeois politics when they were winning so many reforms for the working class, others to defend French liberty from the Kaiser, or German liberty from the Tsar, still others to defeat British finance capital’s grip on the world, or to spark a revolution, or to train the proletariat in the martial spirit for the waging of the class struggle.7 No matter how they justified it though, these socialists were all feeding the proletariat into the meat grinder of imperialist war. There were no progressive belligerents in the First World War. Categories of “aggressor” and “victim” did not apply. It was, as Lenin put it, an “imperialist war for the division and redivision” of the spoils of global exploitation.8

The immediate reaction of those in the socialist movement opposed to the war after the capitulation of so many of the national parties was to organize a series of conferences at Zimmerwald (1915), Kienthal (1916), and Stockholm (1917), to work out a socialist peace policy. At Zimmerwald there soon emerged a left, who favored a policy of class struggle against the war, essentially a revolutionary defeatist position, since carrying it out would detract from the coherence and fighting ability of the armed forces. Lenin sided with this left but said they hadn’t gone far enough, not only did a policy of class struggle against the war, or as he put it: revolutionary defeatism, need to be put forward, but socialists loyal to the international proletariat had to organize themselves separately in order to be able to carry it out.9 This struggle would be a political one, directed at the armed forces of the capitalist state and aiming for their breakup under the pressure of defeatist propaganda and fraternization between the troops of the belligerent countries. On the concrete form of this struggle Lenin wrote, in November of 1914, in The Position and Tasks of the Socialist International:

“War is no chance happening, no “sin” as is thought by Christian priests (who are no whit behind the opportunists in preaching patriotism, humanity and peace), but an inevitable stage of capitalism, just as legitimate a form of the capitalist way of life as peace is. Present-day war is a people’s war. What follows from this truth is not that we must swim with the “popular” current of chauvinism, but that the class contradictions dividing the nations continue to exist in wartime and manifest themselves in conditions of war. Refusal to serve with the forces, anti-war strikes, etc., are sheer nonsense, the miserable and cowardly dream of an unarmed struggle against the armed bourgeoisie, vain yearning for the destruction of capitalism without a desperate civil war or a series of wars. It is the duty of every socialist to conduct propaganda of the class struggle, in the army as well; work directed towards turning a war of the nations into civil war is the only socialist activity in the era of an imperialist armed conflict of the bourgeoisie of all nations.”10

Lenin did not think that the adoption of a revolutionary defeatist position by communists in the imperialist countries was only applicable to the specific conditions of World War I, where the conflict was reactionary on all sides and the proletariat had well developed political organizations in all the belligerent countries who could turn the struggle against the war into an immediate struggle for power. In response to the objection of the Italian socialist leader Serrati to a resolution proposed by the Zimmerwald left that advocated a class struggle against the war, that such a resolution would be moot because the war was likely to end quickly, Lenin said: “I do not agree with Serrati that the resolution will appear either too early or too late. After this war, other, mainly colonial, wars will be waged. Unless the proletariat turns off the social-imperialist way, proletarian solidarity will be completely destroyed; that is why we must determine common tactics.”11 Here, the revolutionary defeatist policy is not simply a path to the immediate struggle for power, as it indeed was in the case of WWI, rather it’s related to the adoption of a particular attitude to the activities of one’s own state in general. For communists in the imperialist countries, this means fighting against the wars your country wages to maintain its grip over its colonies and semi-colonies, using the same tactics you would use in the case of a “dual defeatism” scenario, where communists in all the belligerent countries are defeatist in relation to their country’s war effort, in an inter-imperialist war that is reactionary on all sides.

However, these two scenarios should not be confused. Although Lenin claimed the policy pursued in response to one should be put forward in the case of the other, this should not be extended to the communists in the oppressed country. There is no question of being “defeatist” in relation to a progressive war for national liberation. The Communist International made this clear in condition 8 of its 21 conditions for affiliation:

“Parties in countries whose bourgeoisie possess colonies and oppress other nations must pursue a most well-defined and clear-cut policy in respect of colonies and oppressed nations. Any party wishing to join the Third International must ruthlessly expose the colonial machinations of the imperialists of its “own” country, must support—in deed, not merely in word—every colonial liberation movement, demand the expulsion of its compatriot imperialists from the colonies, inculcate in the hearts of the workers of its own country an attitude of true brotherhood with the working population of the colonies and the oppressed nations, and conduct systematic agitation among the armed forces against all oppression of the colonial peoples.”12

The important point here is that revolutionary defeatism in a predatory imperialist war is only a prescription for communists and proletarian movements in the imperialist countries. Today this means those that benefit from a flow of value coming from global wage arbitrage and the super-exploitation of newly proletarianized former peasants in the former colonial and semi-colonial world. In such a war, the question of defeatism or defensism in the oppressed countries, in the realm of practical policy, is precisely a question for communists in the oppressed countries themselves. This question should be decided on the basis of how best to serve the ends of national liberation and social revolution, taking the particular national political conditions and those of the war into account, but the victory of the oppressed country should be favored over that of the imperialist country.

The Communist International itself may actually have gone too far in the direction of defensism, not in the sense of favoring the victory of the oppressed country, which should always be the case, but in the sense of the relationship of communists in the oppressed countries to their state and to other political forces. Its policy of the anti-imperialist united front was ambiguously formulated and its implementation often involved subordinating the communist parties to the bourgeois nationalist movements. The most notorious example being the case of China, where Comintern directives on the Communist Party’s relationship to the Kuomintang had to be explicitly rejected by Mao and his co-thinkers for the Chinese Revolution to triumph.13 This logic has been taken to the extreme in recent years by the Spartacist League, a far-left sect that has devoted space in their paper to putting forward a position of military support for ISIS: “We take a military side with ISIS when it targets the imperialists and forces acting as their proxies, including the Baghdad government and the Shi’ite militias as well as the Kurdish pesh merga forces in Northern Iraq and the Syrian Kurdish nationalists.”14 The cases of China and modern Iraq and Syria show that sometimes in cases of internal disorder or when the forces “resisting the imperialists” are particularly reactionary, whether the Kuomintang or ISIS, the best option for communists and the anti-imperialist struggle is for communists in the oppressed country to wage a military struggle against both the imperialists and the reactionary forces “resisting” them.

Vietnam

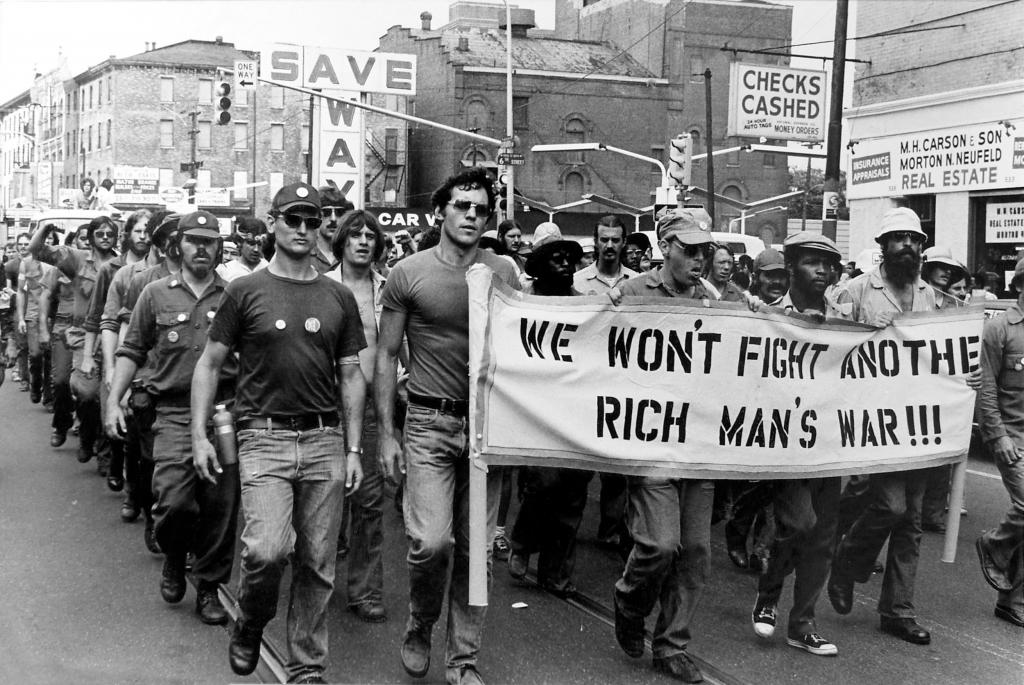

The most successful application of revolutionary defeatist tactics in the US was in the case of the Vietnam war. The best-known images of the anti-war movement in the US are of large public marches and of police repression on college campuses. The truth is that these things were actually pretty ineffective at producing a US defeat and withdrawal. Large demonstrations can do something to turn public opinion against the war and college students were able to take some actions that made a meaningful difference by taking advantage of their positions in a crucial part of the war machine: the university; but these things were not enough to halt the functioning of the most destructive imperialist military in history. We can verify this by comparing the movement against the war in Vietnam with that against the war in Iraq. As with Vietnam, the Iraq war was opposed by millions of demonstrators, including by between 6 and 11 million people on a single day, February 15, 2003, the largest single-day protest in world history; yet the war kept going.15

What was the difference in Vietnam? The answer lies both in the brilliant military strategy of the Vietnamese liberation movement under the leadership of the Communist Party, and in the practical application of a revolutionary defeatist policy by sections of the US far-left and workers’ movement. This meant disrupting the recruitment of the US armed forces, and especially, organizing opposition within the military itself. This resulted in a situation where “search-and-evade” tactics became the ordinary state of affairs for many units, as common soldiers deliberately avoided combat or simulated the appearance and sounds of combat to deceive their officers, over 600 soldiers carried out “fraggings”, murders or attempted murders of their officers, often with frag grenades, and groups of soldiers occasionally carried out organized mutinies. By June 1971 this state of widespread organized resistance to the war led military historian Colonel Robert D. Heinl to write an article titled The Collapse of the Armed Forces, in which he claimed that “The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States.”16 This was undeniably a key factor in the breakdown of US warfighting ability in Vietnam and the eventual US withdrawal.

Some insist that the example of war resisters in the US military during the occupation of Vietnam, and by extension, the entire premise of a policy of active revolutionary defeatism, is entirely useless to today’s revolutionary movement because the nature of the US military has been entirely transformed by the transition to an all-volunteer force in the late-70’s and 80’s. What this position misses is the extent to which the claim that the US military is an all-volunteer force is itself an ideological artifice crafted by the US military establishment and the degree to which poverty itself still acts as a draft. The US military does not make public information on the income-levels or class positions of the families from which it recruits, only their geographic distribution. The fact that the localities that enlistees are drawn from are more affluent than average does not rule out that the enlistees themselves may be poor. The higher cost of living in these areas may in fact be an additional stimulus to enlistment, and the fact that military recruiters regularly use material incentives, like the promise of a free education, to prey on working-class kids, is no secret. This means that the class divide in the armed forces has not entirely been eliminated, that officers’ interests still conflict with those of enlistees, and that the possibility of mass war resistance from within the ranks of the armed forces, especially as part of a coordinated working-class struggle against imperialist war, still lies within reach.

Iran and Third-Campism

With the assassination at the beginning of this year of high ranking Iranian general Qassim Soleimani at the hands of the United States, the prospect of war with Iran became a very real possibility. In fact, a section of the US foreign policy establishment has been hellbent on bombing or invading Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that established the current Iranian regime, and the US has imposed harsh sanctions on Iran that themselves amount to a form of warfare. These sanctions have no doubt contributed to the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran, which has killed 988 and infected over 16,000, roughly 9 in 10 cases in the Middle East.17 Although the immediate worry about an invasion has died down since January, it’s still important for communists to work out what their response to such an invasion would be, because the threat remains on the table.

The main question is whether a revolutionary defeatist policy in relation to a war with Iran should be pursued or whether a Third-Campist position of “Neither Washington nor Tehran” ought to be put forward. The idea of Third-Campism, in this case, is that the political regimes of the United States and of Iran are both so reactionary that the proletariat has no stake in either side’s victory or defeat in the war and should, therefore, neither support nor actively oppose its prosecution by the imperialists. This approach is flawed. If we were considering a war between two imperialist countries on equal standing, both with reactionary governments, what this leaves out is the benefit that the proletariat in both the belligerent countries could gain by an active pursuit of a revolutionary defeatist policy. Either, it could open up the road to the seizure of power by the proletariat in one or both belligerent countries or it could only serve to train the proletarian movement in each country in the art of carrying out a struggle against “its own” state.

However, in the case of a US attack on Iran, this “soft Third-Campist” position of dual defeatism, like that implied by the left-communist International Communist Current, when it describes the Middle East after the Soleimani assassination as “dominated by [an] imperialist free for all” would also be wrong because it regards both the United States and Iran as imperialist.18 Such a war would not be reactionary and imperialist on both sides, a reactionary war by the US for the reconquest of one of its semi-colonies. It is no coincidence that the US only became hostile to the Iranian government after the ouster of its puppet the Shah, meaning that the Iranian war effort would contain elements of a progressive national liberation struggle. In the case of a US invasion, the main enemy for Iranians is not at home, their main enemy is imperialism. Communists in Iran are, of course, opposed to the political regime of the Islamic Republic for its brutal suppression of the workers’ movement and its political organizations, its regressive stance on women’s rights, and its treatment of national minorities, but they do not think it fights too vigorously against US imperialism.19 Communists in the United States should take the position: “better the defeat of US troops than their victory”, and their task would be to carry out an active policy of revolutionary defeatism against an invasion of Iran. The task of communists in Iran would be to fight off the imperialist invaders by any means necessary, including by opposing any effort by the Iranian government to disarm the Iranian proletariat as it prepares itself to resist an invasion.

Third-Worldism

There is another political strand that downplays the importance of active revolutionary defeatist politics in the imperialist countries: Third-Worldism. In this case, it is not the desirability of the proletariat in the imperialist countries carrying out a revolutionary defeatist policy that is questioned, but its political inclination to do so. All this leaves us with is joystick or sideline politics, the cheering on of great revolutionaries and great revolutionary movements, but always happening somewhere else. This makes Third-Worldism a self-fulfilling prophecy, the denial of the ability of the proletariat in the imperialist countries to challenge the imperialist bourgeoisie which exploits both them (usually rationalized by saying that proletarians in the imperialist countries are equally exploiters) and their comrade workers around the world, becomes a reason not to organize to do so. Of course a fraction of the super-profits of imperialism is sometimes distributed to workers in the imperialist countries with the aim of purchasing their loyalty to the bourgeois state. Our point is to build a movement capable of credibly offering something better than that: communism.

The idea that politics flows directly from the movement of money is an economist error, if it were true, all communist politics would be pointless, because that factor will never be in our favor. Rather, international working-class consciousness will necessarily be a subjective product of common struggle, including the anti-imperialist struggle. It is likely, as Trotsky argues in his History of the Russian Revolution, that for reasons of combined and uneven development, the world revolution will be sparked in the oppressed countries first, but that process will not ultimately be successful if revolution does not come to the imperialist countries as well.20 Most great Third-World revolutionaries have been clear about this, Che certainly was. Indeed, as the late Egyptian communist, Samir Amin wrote in Imperialism and Unequal Development:

“…Third-Worldism is strictly a European phenomenon [we may say a phenomenon of the imperialist countries]. Its proponents seize upon literary expressions, such as ‘the East wind will prevail over the West wind’ or ‘the storm centers,’ to justify the impossibility of struggle for socialism in the West, rather than grasping the fact that the necessary struggle for socialism passes, in the West, also by way of anti-imperialist struggle in Western society itself… But in no case was Third-Worldism a movement of the Third-World or in the Third-World.”21

Third-Worldism began as an optimistic reaction to successful national liberation struggles in the oppressed countries in the mid-20th century, but to the extent that it exists today, it is simply a symptom of our defeat. Third-Worldism may produce amusing artefacts like That Hate Amerikkka Beat, but it offers nothing to the practical struggle for global proletarian revolution because it refuses to even consider what might need to be done to make revolution in the imperialist countries. None of this is to discount the work of communists in the Third-World, who are doing their part in fighting imperialism and their bourgeoisie. The problem with Third-Worldism is that it’s a poor form of solidarity that looks not to the ways in which one can most practically ensure the final triumph of those one is in solidarity with.

The Upcoming Battle

The goal of communists in the imperialist countries should be to create, to quote once again Che Guevara, “two, three… many Vietnams”22, not in the sense Che used it, focoistic guerilla campaigns, but in the sense of successful applications of the revolutionary defeatist policy of class struggle against imperialist war, which killed the US military’s ability to maintain the occupation of that country. This means, in the case of unprogressive war, strikes in war industries, spreading defeatist propaganda in the armed forces, and organizing common soldiers against their officers and the war effort. We must also fight for a truly democratic-republican military policy in peacetime, rejecting foreign intervention by the United States and fighting for the universal arming and military training of the people and the right to freely organize in militias for the proletariat, as well as freedom of speech and association for the ranks of the present-day armed forces. “War is the continuation of politics by other means”23 and now is a time of relative peace, a time for politics, a time to build up our forces, to train them to become a honed weapon of class struggle, and “not to fritter away this daily increasing shock force in vanguard skirmishes.”24 But a time of war is coming, and we must have those “other means” at our disposal, we must be prepared to crush our enemies and to use the destructive and atrocious wars conjured up by the bourgeoisie as opportunities to turn the imperialist war into a civil war, to make war on the ruling class as a road to the seizure of power by the proletariat and the triumph of communism.

- Bollag, Burton. “For One Swiss Professor, Vexing His Fellow Citizens Is a Duty and a Delight.” Chronicle of Higher Education, www.chronicle.com/article/For-One-Swiss-Professor/32353.

- Engels, Friedrich. “Letter to August Bebel In Zwickau” London, March 18-28, 1875, Marxists Internet Archive https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/letters/75_03_18.htm

- Mulholland, Marc. “‘MARXISTS OF STRICT OBSERVANCE’? THE SECOND INTERNATIONAL, NATIONAL DEFENCE, AND THE QUESTION OF WAR.” The Historical Journal, vol. 58, no. 2, 2015, pp. 615–640. p. 625

- Engels, Friedrich. “Engels to Marx In London” Manchester, Marxists Internet Archive, 7 October, 1858 https://marxists.catbull.com/archive/marx/works/1858/letters/58_10_07.htm

- Steenson, Gary P. “‘Not one man! Not one penny!’: German Social-Democracy, 1863-1914” University of Pittsburgh Press, 1981 https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735057897393/viewer#page/12/mode/2up

- http://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=3987

- Mulholland.

- Lenin, V. I. “The State and Revolution” Marxists Internet Archive, August 1917 Preface https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/preface.htm

- Macnair, Mike. “Revolutionary Strategy” 2008, November Publications, Chapter 4

- Lenin, V. I. “The Position and Tasks of the Socialist International” Marxists Internet Archive, November 1, 1914 https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/oct/x01.htm

- Lenin, V. I. “The First International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald” Marxists Internet Archive, September 3-8, 1915 https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1915/aug/26.htm

- Lenin, V. I. “Terms of Admission Into Communist International” Marxists Internet Archive, July 1920https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/jul/x01.htm

- Mao, Zedong. “On the Ten Major Relationships” Marxists Internet Archive, April 25, 1956 https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-5/mswv5_51.htm

- “U.S. Out of Near East Now” Workers Vanguard No. 1065, 3 April, 2015 https://www.icl-fi.org/english/wv/1065/neareast.html

- Blumenthal, Paul. “The Largest Protest Ever Was 15 Years Ago. The Iraq War Isn’t Over. What Happened?” Huffington Post, 17 Mar. 2018 www.huffpost.com/entry/what-happened-to-the-antiwar-movement_n_5a860940e4b00bc49f424ecb

- Seidman, Derek. “Vietnam and the Soldiers’ Revolt.” Monthly Review, 27 June 2016, https://monthlyreview.org/2016/06/01/vietnam-and-the-soldiers-revolt/#fn20

- Hasan, Mehdi. “Coronavirus Is Killing Iranians. So Are Trump’s Brutal Sanctions.” The Intercept, 17 Mar. 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/03/17/coronavirus-iran-sanctions/

- “Soleimani assasination: Middle East dominated by imperialist free-for-all” World Revolution 385, Spring 2020 https://en.internationalism.org/content/16809/soleimani-assassination-middle-east-dominated-imperialist-free-all#_ftn3

- Mather, Yassamine. “Explaining the Longetivity of the Theocratic Regime” Weekly Worker October 5, 2011 https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/884/explaining-the-longevity-of-the-theocratic-regime/

- Trotsky, Leon. “The History of the Russian Revolution” 1930

- Amin, Samir “Imperialism and Unequal Development” Monthly Review Press, 1977, p. 11

- Guevara, Ernesto “Che”. “Message to the Tricontinental”Marxists Internet Archive, April 16, 1967 https://www.marxists.org/archive/guevara/1967/04/16.htm

- Clausewitz, Carl von (1984) [1832]. Howard, Michael; Paret, Peter (eds.). On War [Vom Krieg] (Indexed ed.). New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 87

- Engels, Friedrich. “Introduction to Karl Marx’s The Class Struggles in France 1848 to 1850” Marxists Internet Archive March 6, 1895 https://marxists.catbull.com/archive/marx/works/1895/03/06.htm

8 Replies to “The Practical Policy of Revolutionary Defeatism”

Comments are closed.