Amelia Davenport argues for leftist organizers to reclaim the ideas of Taylor’s Scientific Management, making a broader argument for the relevance of cybernetics, cultural revolution in the workers’ movement, and a Promethean vision of socialism. Listen to an interview with the author here.

In my article “Where Does Power Come From?”, I discussed how the communist movement should relate to capitalist society. Though I touched on forms of organization suited to the class struggle such as red unions, cooperatives, tenants’ organizations and so on, I neglected discussing how to conduct the class struggle itself. Symptomatic of leftist theory is a tendency to look at the concrete situation, identify the problem, apply a Marxist (or other) analysis, and present a conclusion to the world. This tendency, however, represents a petty-bourgeois outlook where intellectuals present ideas that they expect workers to struggle toward on their own merits. It is a rationalistic method rather than a scientific approach to organizing. But, while abstract discussion has a role, organizing is a practical science. What is missing is how to get from here to there. While programmatic vision is important for giving direction to organizing, it is impossible to realize your goals without systemic analysis. If you aren’t concretely building towards your goals, everything you say is hot air.

To rectify my failure to bridge the gap between conditions and goals in “Where Does Power Come From,” I surveyed organizational theory. This included both works by major communist thinkers and bourgeois social scientists. Turning to classics like Mao’s On Practice, Bordiga’s The Democratic Principle, and Lenin’s What is to Be Done? was both illuminating and frustrating. These texts either present ready-made tactics or focus on abstract political questions. While they offered useful principles, they didn’t present a useful methodology for reaching new conclusions. On the other hand, when I turned to bourgeois social science, I found a decided lack of social analysis, but a wealth of systemic thought. Bourgeois theorists like Niklas Luhmann use logic and empirical research more advanced than the classics of the communist movement and show how to do the same, but fail to grapple with class contradictions. Even the socialist cybernetician Stafford Beer naively believed in the possibility of a peaceful democratic transition even after the military coup against the Allende government smashed his economic reforms in Chile to bits. Modern theorists of social organization are rarely, if ever, discussed by communists. The movement seems to favor focusing exclusively on a select canon that discovered the truth for all times and places. Leftists ignore almost anyone outside the canon except one theorist who they discuss with the most extreme bile and invective. He is Fredrick Winslow Taylor, father of task management, and one of the most reviled social scientists in the workers’ movement. Whether it is his identification with the Bolshevik government’s turn toward labor discipline or the belief that he is personally responsible for the fact you have to file TPS reports, there is no doubt that Taylor was Satan on furlough from Hell. As all leftists are contrarians, I studied the nature of Taylorism to see if it was of any use to our movement or if it was capitalist hogwash like many believe.

Taylorism and Scientific Management

In Principles of Scientific Management, delivered to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Fredrick Winslow Taylor outlines the nature and methods of his revolutionary framework for the improvement of the world production system. But before he explores concrete steps and methods, Taylor articulates his intention and vision. Taylor wasn’t a socialist, but neither was he a fascist or unsympathetic to the conditions of workers. He wasn’t merely a stooge of capitalist class interests either; he was an ambivalent figure. His goals were threefold:

1) “Maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with maximum prosperity for each employee.”

2) Transforming work so that workers would no longer be either over-strained through exertion or wasting their own time

3) Improving general labor productivity so that the standard of living of the average person might grow through price reduction.

It was Taylor’s belief that by increasing the efficiency of firms, both employers and the workers would benefit. Firms could sell goods faster with a smaller expenditure of labor and equitably distribute the gains.

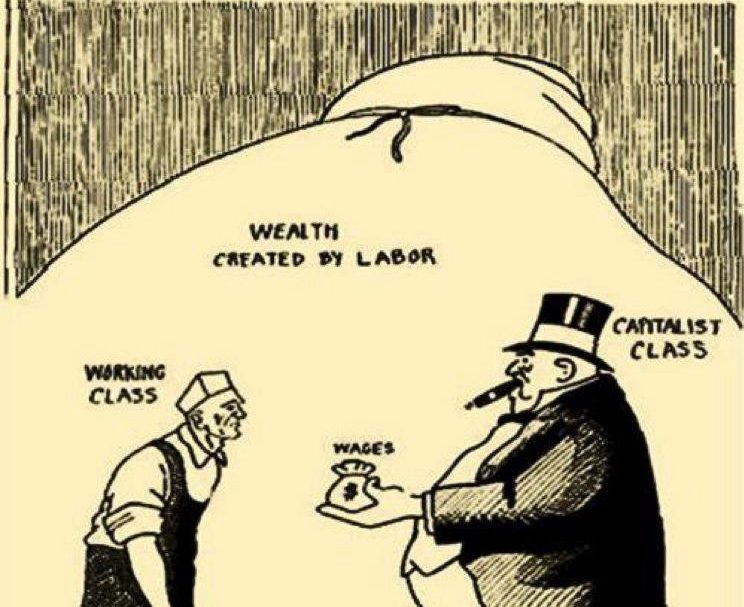

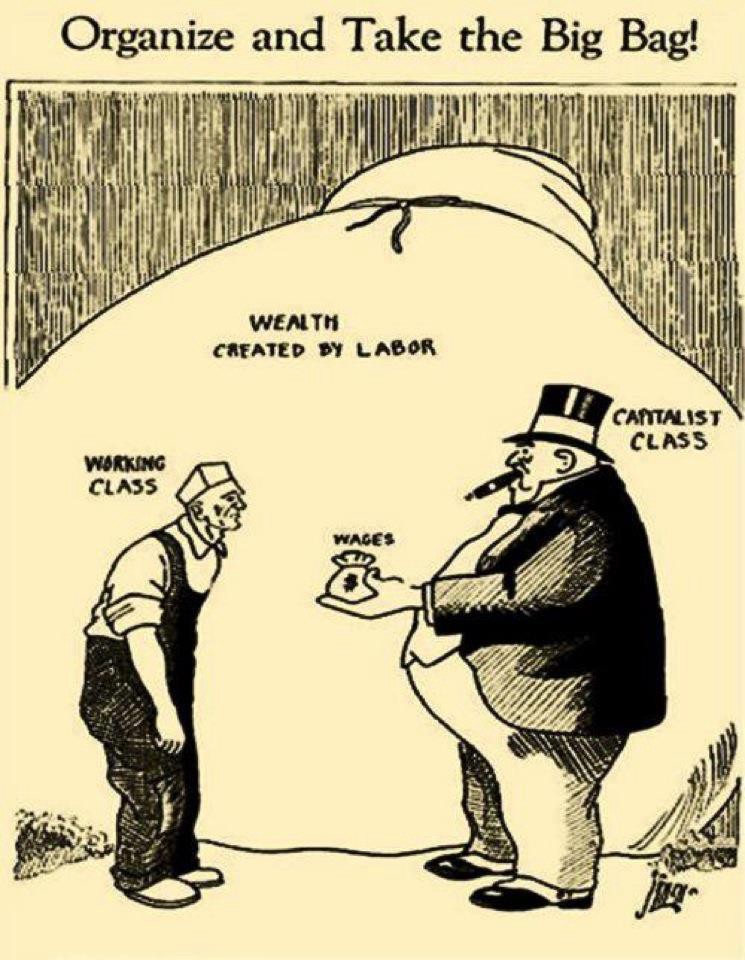

While Taylor largely saw trade unions as a fetter on industrial progress and representing narrow, selfish interests, he recognized that managers and capitalists abused their workers and exploited them. He believed that the introduction of scientific management would heal the contradiction in interests between labor and capital, rationalizing the labor process for the benefit of both. Like his enemies in the American Federation of Labor, Taylor believed that class conflict was reconcilable through the provision of a “fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work.” However, he saw the act of “soldiering”, defined as worker resistance to giving full labor capacity to the capitalists, as the principal obstacle rather than under-incentivization through low wages. The three evils which Taylor cites as the cause of “soldiering” are:

1) The fallacy that increasing the material output of labor will result in higher unemployment

2) The defective systems of management which make it necessary for workers to work as little as possible to protect their own interests

3) “Rule of thumb” methods which cause people to waste their efforts for little purpose.

Taylor claims that there are two immediate reasons people “soldier.” First, there’s “systemic soldiering”, where workers collectively discipline one another to work slower so that there’s work for all. Second is the fact that employers set a fixed wage for a given quantity of labor time (or amount of goods that the capitalist thinks workers can produce in that amount of time in a piece-work system) largely based on past rates. This means the workers have an incentive to produce as little as possible in a given period so has to avoid working harder for no extra reward in the future. Taylor claims that the only recourse employers have in this scenario is the threat of unemployment which pits management and workers against each other. Conversely, while the “whip” of unemployment drives the workers, management remains “hands-off” and leaves the full responsibility of completing the work to the workers themselves. Management fails to educate workers in the best methods to conduct work with their expanded knowledge of the labor process. Managers also fail to understand the condition of the labor and thereby fail to direct it properly, furthering conflict. Instead, Taylor recommends management share in work equitably. Despite recognizing that antagonism between workers and employers exists, Taylor believes this antagonism is solvable.

To socialists, the notion that the contradiction between labor and capital is reconcilable by improving the lot of labor within capitalism is prima facie incorrect. But must we toss out the entirety of Taylorism as a bourgeois scam? What about conditions where the contradiction between capital and labor is nonexistent, such as a socialist society where the cooperative commonwealth of toil reigns, or within the organizations of militants struggling to overthrow capitalism?

Dispelling Myths

Scientific Management

Setting these questions aside for now, we will look at what scientific management is and what it is not. For Taylor, scientific management is emphatically not a set of techniques that an organization can adopt to improve efficiency and profit. Instead, scientific management is a philosophy of organization which when applied to different contexts and with different objectives necessarily requires different techniques. This isn’t unlike Marxism, which, as a scientific philosophy, requires a creative application and offers different strategies depending on the objective conditions. While in one context standardizing the motions used for say shoveling coal might both improve the output and decrease the strain on the body of the worker, in another context standardizing motions, like in detail painting, might produce the opposite effect. In particular, Taylor concerns himself with the misapplication of techniques creating dissatisfaction among workers. Issues could emerge from a lack of proper education on the benefits of a given techniques or through the introduction of harmful methods. Certain techniques may cause harm to workers without the use of other innovations that address these problems. Taylor claims that his philosophy can revolutionize production if applied properly.

Understanding scientific management’s role requires knowing what it replaced. Before Taylor, employers organized labor based on what Taylor calls “management by initiative and incentive.” Initiative is the “hard work, good-will, and ingenuity” of the workers. In trades where there is no systemic organization of labor, it is each worker who has in their possession the accumulated knowledge, built up over generations, for how to conduct the work. It is on the workers’ own individual initiative that they labor. Management’s role is motivating workers to use their knowledge and physical skill to complete the work. Even if a firm draws management from the ranks of the most skilled workers, they cannot hope to match the combined knowledge of their employees. Managers have three tools in this system:

1) Positive incentives like the promise of promotions, raises, and better personal working conditions relative to other workers

2) Negative incentives like the threat of firing or loss of pay

3) The personal charisma of the manager and rapport they build with the workers.

If a firm doesn’t wish to pay beyond the average, it must surveil its workers so they tear into the work. A firm using this model relies on spies who hope for personal advancement.

Now, what does scientific management philosophy itself consist of? Listening to some leftists, you’d think it was totalitarian-rational control over the bodies of workers to extract ever-increasing labor or a synonym for the increased domination of capital over the lives of workers. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In reality, one of Taylor’s goals was the education of workers so they can control and discipline their own actions. More than anything, scientific management is the systemic organization and rationalization of the tasks of labor so that they can be divided equitably according to ability. Rationalizing production also ensures laborers meet the needs of the productive process. There is a diverse array of elements that scientific managers must utilize in concert or else the system will fail to produce the desired results. In Taylor’s vision, the principal aspects of scientific management are:

1) The development of a true science (of the particular labor process);

2) The scientific selection of workers and the scientific education and development of the workers;

3) Intimate, friendly cooperation between management and the workers.

Initiative and Incentive in Leftist Organizing

The “initiative and incentive” model of management is the standard method of leftist groups. “Organizers,” through their personal charisma and promise of winning immediate gains, incentivize people to use their initiative towards their campaigns. Group members receive general tasks and an expectation to complete them, either by themselves or with a few other people. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the top-down orders of the leadership or democratic vote by the group; activists are tacitly encouraged to take on an unsustainable load, leading to burnout. Organizers don’t teach activists to draw healthy boundaries between their own needs and what is reasonable to contribute. If they don’t burn out, activists drop out as they lose interest in work that comes to seem increasingly futile. Motivating activists in leftist organizations is a mixture of generating enthusiasm through charismatic interventions by leaders (whether they consider themselves leaders or not) or through peer pressure and guilt which organizers leverage to build commitment. The routine “cancellation” of leftists by activists and policing of cultural consumption are examples of mechanisms for disciplining activists to the will of organizers. While leaders may participate in the work directly, in vanguardist sects their role is to focus on developing theory and broad strategy. In the case of horizontal sects, organizers perform the same work as other rank-and-file members to the same results. How the socialist left can escape this trap will be further explored later in the text.

Can Labor Be Scientific?

To understand scientific management, these elements must be explained in turn.

The development of a true science of labor is the cornerstone of the philosophy of scientific management. After “soldiering” by workers and management based on incentivization, the greatest object of scorn in Taylor’s mind is the “rule of thumb” method of organizing work. Most work before Taylorism was conducted based on “common sense” and received wisdom. But the distribution of this “wisdom” is uneven and varies based on the prejudices and experience of those retaining it. For instance, one restaurant might at the start of the day employ the chef to chop a particular vegetable, while another might employ a sous-chef to chop the vegetable as needed as a part of their varied tasks throughout the day. Neither restaurant knows the better method, nor if there might be a third option which could prove superior. To develop a science, a restaurant would test the different methods of preparation to see which wasted the least material and used the fewest net hours of labor to create a saleable product.

In leftist organizing, rules of thumb constitute the predominant method used by semi-successful sects. More often though, leftists don’t even rise to the level of handmade or received philosophies on the subject and are either re-inventing the wheel or engaging in senseless activities. To illustrate, some communists believe that the creation and distribution of ironic memes constitute revolutionary activity or that taking on unpaid moderator positions for social media companies meaningfully contributes to the class struggle.

What are some examples of rules of thumb that leftists employ? Today these examples manifest as the various tactics taken as articles of faith by organized leftist groups. Of particular note is the theory of the “vanguard party,” along with its necessary complement, “democratic centralism” (and sometimes the “mass line”). Many sects define themselves by tactics like newspaper sales, electoral campaigns, entryism into business unions, and so on. They take these tactics as articles of received wisdom from whichever communist saint they believe the “red thread” of revolutionary legitimacy passes through. Anarchists are by no means exempt from this. Their fetishes of decentralization, “grassroots” organization (something shared with many Trotskyist and Maoist sects), propaganda of the deed, syndicalism, direct service projects, and permaculture serve the same role. This doesn’t mean that any of these listed articles of faith are wrong. It is possible that in different contexts each may be a necessary tactic or method. Through the application of social scientific analysis, we may discover that in one set of conditions the development of localized food systems is part and parcel of the socialist transformation of society. On the other hand, it may be the case that centralized agriculture is the best way to sustainably feed the masses while using as little land as possible. More important than any given conclusion is how we reach those conclusions, because it means that as conditions change, so too can the strategies the revolutionary movement uses to meet those conditions.

After we tentatively settle these broad strategic questions, we must uproot rules of thumb within the application of strategy. Take the mass line. Instead of the Maoist slogan “from the masses, to the masses,” which a skilled organizer must interpret based on repeated trial and error, the mass line should incorporate real social psychology, systemic investigation, and quantitative analysis. Simply gathering demands of workers and reformulating them in the language of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism is not scientific. Better would be breaking down the aspects of the mass line into its constituent parts and systematizing them. If made scientific, any worker could use the mass line, not just skilled organizers. An outline of a scientific mass line is: 1) the social inquiry; 2) finding winnable demands; and 3) organizing for the identified demands. Each of these three components themselves involve considerable work and analysis. To begin a social inquiry, an organizer must 1) identify and assess their constituency; 2) determine what questions they want to ask; and 3) determine how to reach the masses. Breaking down the other two sections will likewise be necessary. This will extend down to concrete tasks like canvassing a specific neighborhood or conducting a workers’ inquiry. It is by breaking things into their constituent parts that we can begin to understand a strategy and test methods and develop a true science of that particular type of organization.

Taylor applied the scientific organization of labor at Bethlehem Steel. He started by developing an improved method of shoveling pig iron. This was an opportunity afforded by a rapid spike in demand for the product after years of a glut:

We found that this gang were loading on the average about 12 ½ long tons per man per day. We were surprised to find, after studying the matter, that a first-class pig-iron handler ought to handle between 47 and 48 long tons per day, instead of 12 ½ tons. This task seemed to us so very large that we were obliged to go over our work several times before we were absolutely sure that we were right. Once we were sure, however, that 47 tons was a proper day’s work for a first-class pig-iron handler, the task which faced us as managers under the modern scientific plan was clearly before us. It was our duty to see that the 80,000 tons of pig iron was loaded on to the cars at the rate of 47 tons per man per day, in place of 12 ½ tons, at which rate the work was then being done. And it was further our duty to see that this work was done without bringing on a strike among the men, without any quarrel with the men, and to see that the men were happier and better contented when loading at the new rate of 47 tons than they were when loading at the old rate of 12 ½ tons.

Before Taylor began working at Bethlehem Steel, he had discovered the scientific law governing high-strain labor. High-strain labor is the kind that involves lifting heavy objects or pushing for a continuous period. Taylor began this study to reconcile the interests of management, on whose side he stood, with the interests of the laborers. Management wanted a higher output and laborers wanted to not be overworked. Workers saw no real benefit to intensifying their labor, which Taylor recognized. He attempted to calculate a specific amount of horsepower a worker could exert in a day without damaging their body. But this was to no avail: despite finding much useful data in his experiments, Taylor and his team could find no rule that governed how hard someone could work in strenuous activity by themselves. So they brought in a mathematician named Carl G. Barth. Because of Barth’s mathematical knowledge, the team represented the data graphically and through curve charts. This allowed the engineers to identify the factors which determine the principle law of high-strain labor. Taylor says:

The law is confined to that class of work in which the limit of a man’s capacity is reached because he is tired out. It is the law of heavy laboring, corresponding to the work of the cart horse, rather than that of the trotter. Practically all such work consists of a heavy pull or a push on the man’s arms, that is, the man’s strength is exerted by either lifting or pushing something which he grasps in his hands. And the law is that for each given pull or push on the man’s arms it is possible for the workman to be under load for only a definite percentage of the day. For example, when pig iron is being handled (each pig weighing 92 pounds), a firstclass workman can only be under load 43 per cent. of the day. He must be entirely free from load during 57 per cent. of the day. And as the load becomes lighter, the percentage of the day under which the man can remain under load increases. So that, if the workman is handling a half-pig, weighing 46 pounds, he can then be under load 58 per cent. of the day, and only has to rest during 42 per cent. As the weight grows lighter the man can remain under load during a larger and larger percentage of the day, until finally a load is reached which he can carry in his hands all day long without being tired out. When that point has been arrived at this law ceases to be useful as a guide to a laborer’s endurance, and some other law must be found which indicates the man’s capacity for work.

When a laborer is carrying a piece of pig iron weighing 92 pounds in his hands, it tires him about as much to stand still under the load as it does to walk with it, since his arm muscles are under the same severe tension whether he is moving or not. A man, however, who stands still under a load is exerting no horse-power whatever, and this accounts for the fact that no constant relation could be traced in various kinds of heavy laboring work between the foot-pounds of energy exerted and the tiring effect of the work on the man. It will also be clear that in all work of this kind it is necessary for the arms of the workman to be completely free from load (that is, for the workman to rest) at frequent intervals. Throughout the time that the man is under a heavy load the tissues of his arm muscles are in process of degeneration, and frequent periods of rest are required in order that the blood may have a chance to restore these tissues to their normal condition.

It is in this way that Taylor and his associates scientifically organized the work of pig-iron handlers. This is not the only example he provides in Principles of Scientific Management; Taylor also discusses the application of the method to skilled work. At a manufacturer of machines, he set out to double the output using the same number of workers and machines as before. Despite the fact the foreman doubted the possibility, Taylor proved his claims through a demonstration on a machine selected by the foreman:

The machine selected by him fairly represented the work of the shop. It had been run for ten- or twelve-years past by a first-class mechanic who was more than equal in his ability to the average workmen in the establishment. In a shop of this sort, in which similar machines are made over and over again, the work is necessarily greatly subdivided, so that no one man works upon more than a comparatively small number of parts during the year. A careful record was therefore made, in the presence of both parties, of the time actually taken in finishing each of the parts which this man worked upon. The total time required by him to finish each piece, as well as the exact speeds and feeds which he took, were noted, and a record was kept of the time which he took in setting the work in the machine and removing it. After obtaining in this way a statement of what represented a fair average of the work done in the shop, we applied to this one machine the principles of scientific management.

By means of four quite elaborate slide-rules, which have been especially made for the purpose of determining the all-round capacity of metal-cutting machines, a careful analysis was made of every element of this machine in its relation to the work in hand. Its pulling power at its various speeds, its feeding capacity, and its proper speeds were determined by means of the slide-rules, and changes were then made in the countershaft and driving pulleys so as to run it at its proper speed. Tools, made of high-speed steel, and of the proper shapes, were properly dressed, treated, and ground. (It should be understood, however, that in this case the high-speed steel which had heretofore been in general use in the shop was also used in our demonstration.) A large special slide-rule was then made, by means of which the exact speeds and feeds were indicated at which each kind of work could be done in the shortest possible time in this particular lathe. After preparing in this way so that the workman should work according to the new method, one after another, pieces of work were finished in the lathe, corresponding to the work which had been done in our preliminary trials, and the gain in time made through running the machine according to scientific principles ranged from two and one-half times the speed in the slowest instance to nine times the speed in the highest.

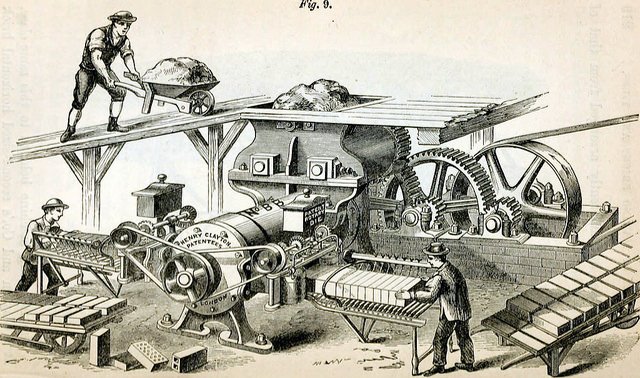

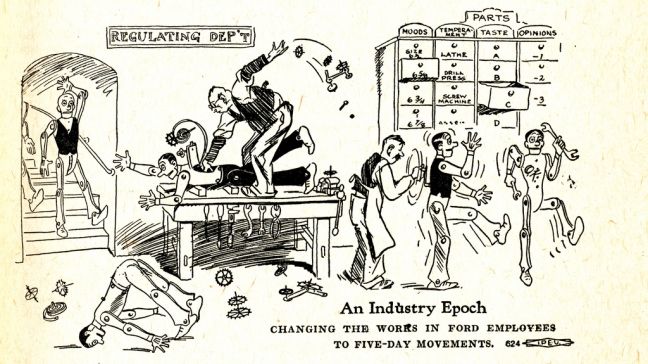

But Taylor’s reforms involved more than changes to the machines. The principle aspect was the mental change scientific management produced in the workers. On the one hand, it required workers to endorse using scientifically selected hand motions, and on the other it needed a mental investment in the new system. Each worker received on average 35 percent greater wages but produced over double the amount of goods in the same time. This motivation to contribute a greater force of labor is as important as any technical improvements to the forces of production to scientific management. But also key is how Taylor brought in unskilled laborers to work on the improved machines rather than the skilled workers previously employed. Elevating people from lower to higher work increased buy-in and expanded the labor pool available for this work and proletarianized the formerly skilled artisans. In this way, Taylorism has a dual character. Under capitalism, it increases the exploitation of labor by intensifying work while costing skilled tradesmen their jobs. But, Taylorism also makes work accessible to a broader array of workers while also growing real wages as a share of the increased productivity. It is not unlike how Marx observed that the concentration of the forces of production by capitalism itself both impoverished the working class but also creates the means by which the working class can achieve abundance.

The Social Division of Labor

It is important to ground ourselves in the real experiences of the working class with the technologies that govern our lives. Within an Amazon fulfillment center, the labor discipline imposed through intensified and semi-automated task-management creates conditions that are degrading and inhumane. Workers have every moment of their time monitored and directed towards only those activities which are necessary to fill orders. In real terms this means people driven to exhaustion and nervous collapse so that the firm can extract more money faster. It may appear that these technologies are the source of workplace oppression, enforcing incessant imperatives towards productivity. Yet behind this imperative towards productivity is the same logic of capital that existed before the introduction of these technologies. Many on the Left have the mistaken belief that a return to less technically developed forms of labor would restore dignity. It’s a sad mistake. While they have more autonomy than fulfillment workers, capitalism drives in-home hospice nurses to the same level of desperation as Amazon workers. Hospice nurses, working out of a hospital in my own area, are reduced to pissing themselves to fulfill their unrealistic quotas. They simply don’t have time to take breaks in between patients. Even as these nurses are driven to such degrading lows on the clock, ever more necessary paperwork is shifted off the clock so that the hospital can extract more unpaid work. There are no electronic monitoring systems guiding workers there, and they don’t even work under a supervisor. Yet the same basic logic of capital accumulation creates almost identical subjective effects. Even though the nurses have employer-matched retirement savings, high wages, healthcare, and more autonomy, they are still brutally exploited within the labor process. Conversely, when the confluence of history combined task management with powerful labor unions during the postwar compromise, the technical division of labor became a source of workers’ empowerment. Unions could prevent managers from shifting unpaid work onto employees by contractually limiting them to only the specific work in their job description, the very descriptions that the Taylorist system created. Anti-union pundits cite this as an example of economic irrationality, but it meant more free time within the labor process and a general lower intensity of labor. This is why Marx, though sympathetic to their plight, spoke of the futility of the Luddites. They were militant artisans, followers of a mythic “King Ludd” who smashed the machines used to simplify and intensify their labor. Rather than a return to artisanal labor, Marx called for the overthrow of capitalism. Instead of smashing machines, the answer was a transfer of control over the instruments of labor to those who used them.

While it contains an emancipatory current within it, Taylor’s thought also contains elements that serve to buttress bourgeois society against this current. These come to the fore in his views on the division of labor. Taylor claims that neither the de-skilled laborers who took over the work, nor the narrowly skilled laborers using the old methods, understand the science necessary to systematically improve their work due to their narrow specialization. He says:

It seems important to fully explain the reason why, with the aid of a slide-rule, and after having studied the art of cutting metals, it was possible for the scientifically equipped man, who had never before seen these particular jobs, and who had never worked on this machine, to do work from two and one-half to nine times as fast as it had been done before by a good mechanic who had spent his whole time for some ten to twelve years in doing this very work upon this particular machine. In a word, this was possible because the art of cutting metals involves a true science of no small magnitude, a science, in fact, so intricate that it is impossible for any machinist who is suited to running a lathe year in and year out either to understand it or to work according to its laws without the help of men who have made this their specialty. Men who are unfamiliar with machine-shop work are prone to look upon the manufacture of each piece as a special problem, independent of any other kind of machine-work. They are apt to think, for instance, that the problems connected with making the parts of an engine require the especial study, one may say almost the life study, of a set of engine-making mechanics, and that these problems are entirely different from those which would be met with in machining lathe or planer parts. In fact, however, a study of those elements which are peculiar either to engine parts or to lathe parts is trifling, compared with the great study of the art, or science, of cutting metals, upon a knowledge of which rests the ability to do really fast machine-work of all kinds.

The real problem is how to remove chips fast from a casting or a forging, and how to make the piece smooth and true in the shortest time, and it matters but little whether the piece being worked upon is part, say, of a marine engine, a printing-press, or an automobile. For this reason, the man with the slide-rule, familiar with the science of cutting metals, who had never before seen this particular work, was able completely to distance the skilled mechanic who had made the parts of this machine his specialty for years.

It is true that whenever intelligent and educated men find that the responsibility for making progress in any of the mechanic arts rests with them, instead of upon the workmen who are actually laboring at the trade, that they almost invariably start on the road which leads to the development of a science where, in the past, has existed mere traditional or rule-of-thumb knowledge. When men, whose education has given them the habit of generalizing and everywhere looking for laws, find themselves confronted with a multitude of problems, such as exist in every trade and which have a general similarity one to another, it is inevitable that they should try to gather these problems into certain logical groups, and then search for some general laws or rules to guide them in their solution. As has been pointed out, however, the underlying principles of the management of “initiative and incentive,” that is, the underlying philosophy of this management, necessarily leaves the solution of all of these problems in the hands of each individual workman, while the philosophy of scientific management places their solution in the hands of the management. The workman’s whole time is each day taken in actually doing the work with his hands, so that, even if he had the necessary education and habits of generalizing in his thought, he lacks the time and the opportunity for developing these laws, because the study of even a simple law involving say time study requires the cooperation of two men, the one doing the work while the other times him with a stop-watch. And even if the workman were to develop laws where before existed only rule-of-thumb knowledge, his personal interest would lead him almost inevitably to keep his discoveries secret, so that he could, by means of this special knowledge, personally do more work than other men and so obtain higher wages.

Under scientific management, on the other hand, it becomes the duty and also the pleasure of those who are engaged in the management not only to develop laws to replace rule of thumb, but also to teach impartially all of the workmen- who are under them the quickest ways of working. The useful results obtained from these laws are always so great that any company can well afford to pay for the time and the experiments needed to develop them. Thus under scientific management exact scientific knowledge and methods are everywhere, sooner or later, sure to replace rule of thumb, whereas under the old type of management working in accordance with scientific laws is an impossibility.

Taylor’s logic here is that it takes education in the general principles that govern something to understand it and create a particular science, that the average worker would not have this knowledge, and that even if they did, they could not deploy it while working full-time in their trade. For him, this means that it is necessary to employ scientists as managers for the supervision of labor. Though blinded by his petty-bourgeois class position, believing that only a certain class of men could do science, Taylor is grasping towards a truth essential to the foundation of the communist worldview. We must create universal and general science, and only with a holistic vision can we solve the problems of social organization. The narrow views of individual positions aren’t enough. Taylor’s objection to the educated machine-worker being able to apply science to his work dissolves when applying the labor-saving potential of increased productivity to the reduction of the workday. With a reduced workday, any given worker would have the free time to “take a stop-watch” to conduct time studies for figuring out better methods. Likewise, in the co-operative commonwealth, as workers collectively own production, so too do they directly benefit from the generalization of labor-saving techniques. The question isn’t whether or not time and motions are measured, it’s “who controls the time and motions?”

Taylor’s first step in introducing scientific management was to scientifically select the workers who would be most likely be able to handle the higher rate of pig-iron and had an industrious character. Taylor and his associates took each man for training, one at a time, because the object of scientific management is developing each person according to their ability rather than treating people as uniform cogs in a machine. They began by promising their first subject, Schmidt, an increase in pay in exchange for following their explicit instructions. As someone particularly motivated by money, Schmidt assented. Rather than try to convince and motivate him to increase his output to a level much higher than was normal, Taylor sought to show his subject in practice that he was capable of doing so and how to do it.

Schmidt started to work, and all day long, at regular intervals, was told by the man who stood over him with a watch, “Now pick up a pig and walk. Now sit down and rest. Now walk — now rest,” etc. He worked when he was told to work, and rested when he was told to rest, and at half-past five in the afternoon had his 47 ½ tons loaded on the car. And he practically never failed to work at this pace and do the task that was set him during the three years that the writer was at Bethlehem. And throughout this time he averaged a little more than $1.85 per day, whereas before he had never received over $1.15 per day, which was the ruling rate of wages at that time in Bethlehem. That is, he received 60 per cent. higher wages than were paid to other men who were not working on task work. One man after another was picked out and trained to handle pig iron at the rate of 47 ½ tons per day until all of the pig iron was handled at this rate, and the men were receiving 60 per cent more wages than other workmen around them.

Taylor believed that those best suited to arduous manual labor were also least suited to intellectually understanding the science of labor that they were enacting. He compares their minds to those of oxen. There is no doubt that Taylor, a man of the early 20th century, not unlike many Marxists at the time, subscribed to eugenicist and elitist views of human biology. Taylor, contra Marx, but in conformity with bourgeois and aristocratic theories of social organization, believed that individuals are meant to specialize within narrow trades that they are optimally suited for. He wasn’t merely a proponent of the technical division of labor; he was a proponent of the social division of labor. Though we can and should dispense with the eugenicist bias in Taylor’s own approach, it does not mean that scientific selection itself isn’t a necessary part of organizing any large-scale endeavor. People have different inclinations, different traits, and different areas in which they have developed themselves. One person might be stronger physically than another, or more gifted with languages. However, these differences are not the sole domain of genetics or other immutable factors, and they do not create an intractable hierarchy of capacity. While within one’s own organism one might have a lower ability to lift heavy objects than another, our society has developed countless methods of adaptation to render this difference superfluous. An ever-growing number of people use prosthetics and other forms of technology to enhance their natural capacities. Likewise, one might have a poor memory, but by maintaining a journal or notepad there’s no functional difference in outcomes compared to someone with an average memory when trying to recall a piece of information. Humans have always been cyborgs. It isn’t anything innate to a particular human organism that enables this, but rather collective intelligence and cooperation which gives rise to the overcoming of limitations. Likewise, jargon simplifies and eases the work for people with a sufficient background but excludes those without it. Many of the barriers to learning are artificial and socially established. According to Taylor, Schmidt could never understand why he should take regular breaks when he worked. He would naturally over-strain himself by laboring as hard as possible straight through. But this strains credulity. It seems more like a failure on the part of Taylor to adequately explain his science. Or maybe Taylor’s narrative is a post hoc justification for capital’s unwillingness to allow him to train men like Schmidt to run production by themselves.

Class Leadership

For revolutionaries, the uneven distribution of skill is a challenge to overcome. The ability to conduct a meeting, do accounting, create propaganda, give a speech, take minutes, edit a publication, maintain a community garden, and so on are skills which it is necessary for as many members of the movement to possess as possible. Some people may have an inclination towards one area, but it is critical for organizers to move beyond their comfort zones and take on new expertise. Revolutionary organizations must not end up dependent on a few people. But just as much as up-skilling members, it means de-skilling the work. Simplifying meeting procedure, using QuickBooks, fundraising through Chuffed, employing automated graphic design templates on Canva, using an email marketing platform like MailChimp, and so on are examples of how we can streamline the necessary work of organization.

But, while communists must discard Taylor’s commitment to an essentialist view of ability, individuals do have different attributes which make them suited for different kinds of work. Proven loyalty and soundness are as important as skill and inclination. Soundness is a function of how good someone’s judgment, reliability, and trustworthiness are. Taylor does not address this area because in capitalist firms the threat of termination and promise of financial promotion is enough to discipline most workers. Many tasks involve levels of responsibility that require a significant amount of trust. In revolutionary situations, peoples’ lives are in the hands of leaders and seasoned people are needed for those jobs. Likewise, not just anyone can serve as the public face of a campaign; considerations like public image and personal reliability become far more important in such situations. If it came out that the spokesperson for a tenant’s rights group had, unbeknownst to their comrades, threatened or assaulted their landlord, it could serve to discredit the entire organization in the eyes of the public. Just as important when it comes to soundness are roles involving financial responsibility. All too often in the movement have charismatic people wormed their way into positions of trust from which they can embezzle from or defraud their comrades for selfish aims. Louis C. Fraina is a famous example from the early movement in the US. Fraina helped found the Communist Party out of the left-wing of the Socialist Party. As an agent of the Communist International in Mexico, he embezzled considerable funds. Fraina was a gifted writer and speaker which fooled the far-off Comintern officials into trusting him despite the suspicions of the comrades he worked with. After being cleared of charges of being a spy for the US government, he stole between four and fourteen thousand dollars.1 Fraina quit the movement, claiming that factionalism and dogmatism drove him away. Even though Fraina was seen as too suspect and divisive to return to the American party, and clearly had factors pushing him away from unity with his comrades, the Comintern foolishly trusted him with an enormous sum of money.

Soundness is a framework for scientific selection that allows us to attenuate (though not eliminate) the negative effects of personality and personal relationships in leadership. It’s through objective metrics without relying on the essentialization of traits that we can measure soundness. This is not to deny that there is a rational kernel to personality politics; collegiality is a factor in determining reliability. If someone is unable to work with others in a friendly or respectful manner, they can’t accomplish the goal of collective liberation. Likewise, there is a real basis for looking at ability when determining qualification for a job. Education and what innate gifts one brings to the table have a serious impact on one’s ability to accomplish a task. If you understand how to do double-entry bookkeeping, you can consistently do good accounting. If you have gifts in mathematics, you will be better able to adapt to situations where aids like computer software aren’t available. Regardless, it is important to keep three things in mind when discussing individual ability:

1) Any individual can be elevated to a higher level of competence through education.

2) Many of the obstacles to functional ability are artificial. Society creates barriers through social dynamics like unnecessary formalization or insufficient clarity.

3) Access can be expanded in any type of work; it’s just a matter of committing resources to do so.

Action proves reliability. If someone shows they can handle smaller tasks with lower stakes, the movement can trust them with larger, complex tasks. But, failing to complete tasks isn’t an individual moral failing. Their comrades should apply themselves to solving the issue of reliability. We solve problems by identifying the concrete source of the issue and mitigating or solving it. When someone repeatedly fails to show up to actions because of parental responsibilities, providing childcare may be an appropriate solution. If a union committee member fails to do a one-on-one they signed up for out of nervousness, it is an opportunity to boost their morale and confidence. Increasing reliability has positive benefits for individuals just as much as for the group; it serves as a direct and immediate means to transformatively benefit those who participate in class struggle.

It is all well and good to talk about soundness in the abstract, but if we are to take anything positive from Taylorism it is the impetus toward quantifiable metrics and concrete rubrics. What does that look like in practice? The best example we have today is the ranking system promoted in the Industrial Workers of the World’s “Organizer Training 101.” In union campaigns, the fulcrum of the organizing effort is a select group of the most class conscious and reliable members of the shop. This group, referred to as the “committee,” conducts repeated and sustained analysis of the conditions of the shop to guide strategy. Most important for our purposes is the “assessment.” When a committee assesses someone in the shop, they assign them a rank between one and six. This rank is based on how committed to the union a worker is. The most committed people in the shop are 1s while the most hostile are 5s. 6s are those whose position the committee is ignorant of. Committee members don’t assess someone’s position on expressed sentiments alone, though they do take statements of sympathy or opposition into consideration. To be a 1, you have to both express sympathy and do concrete tasks for the union. Taking on tasks not only shows support beyond words, it builds commitment and creates a stake in the success of the union. Everyone in the committee must be a 1 and the committee should include as many of the 1s as is feasible once it begins to become more public. To be a 2 you need to have expressed support for the union and not have recently done any tasks to support it; it is possible to go down from a 1 to a 2 if you repeatedly fail to do your tasks or refuse to take any on. A 3 is someone who is at an intermediate level of alignment to the campaign and either has stated that they have no opinion or has given mixed opinions but has taken no action either way. A 4 is someone who has expressed negative views about the union, unions in general, or the actions of the committee but who has taken no concrete actions against the union. Organizers should never write off 4s, and through the course of a campaign, they can often become 1s. A 5 has taken concrete steps against the union or their coworkers. They might have snitched on someone, tried to talk a coworker out of supporting the union, or engaged in bigoted behavior. Sometimes 5s can be won over and the committee should make every effort to do so, but as long as they are 5s the committee needs to marginalize them within the shop. Quarantining the destructive behavior of 5s is critical. Every member of the committee should rank each member of the shop, including themselves. This helps mitigate biases and allows cross-comparison. Often one organizer will have different information than another or interpret the same information differently. This ranking system allows the organization to strategize with real data and figure out what actions to take to uplift their coworkers to a greater level of reliability. The IWW ranking system is just one example of how to quantify soundness in a simple, straightforward, and easy to implement manner.

If we use reliability as our metric for selection and seek to break down the social division of labor, it is necessary to build up reliability among all cadre and members of working-class organizations. And if reliability is a priority, how is it cultivated in practice? Here Taylor comes back into the picture. Within scientific management, the individual scientific education and training of workers is fundamental. This has three principal goals:

1) To teach workers the means to conduct their work according to the methods developed through scientific analysis;

2) To demonstrate to workers why these new methods are superior to the old methods while avoiding industrial disruption due to insufficient support built up for the new system;

3) To continually ensure that workers can meet the challenges of production.

Basic to the framework of scientific management is treating each worker as an individual whose needs in the labor process are unique, not as an interchangeable cog. Training in scientific management takes three forms:

1) The elevation of a worker from the old rule-of-thumb methods to scientific methods;

2) Functional supervision which breaks up the tasks of management into several roles;

3) Giving each worker detailed and specific instructions for the work they are to carry out each day on a card.

By breaking down the work into clear and understandable instructions, people can immediately begin their assigned tasks and complete them with as little room for error as possible. People don’t generally want to have to figure out each necessary task for themselves every time they work. It is much more desirable to just know how you can contribute. These components are important for any organization that wants to ensure its members use their limited time as effectively as possible.

Building Our Communities

If the “management by initiative and incentive” so dominant on the left is ineffective, how do we motivate people to take on tasks? There are two methods to use in conjunction. The first is to identify and constitute a community of shared interests. Let’s use the example of a labor union. Labor unions root themselves in the shared interests of the workers against the bosses. Likewise, a tenants union grows from a shared interest against the landlords, a serve-the-people grocery project comes from the shared interest in ending the risk of hunger in one’s own community, and a cultural group is a function of a shared interest in edification and recreational enjoyment. There’s a real stake in the success of the project for the constituency. Such communities of interest do not emerge organically: organizers consciously build them. By default, most people are content to suffer whatever abuses their bosses and landlords heap on them because that’s what society taught them they should accept. It takes agitation and education to overcome this and bring people together into identifying with one another and their common cause.

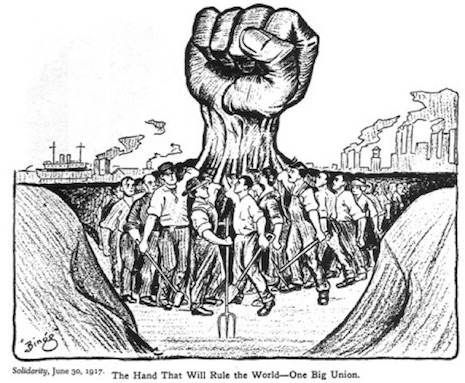

It is out of direct communities like unions, mutual aid societies, and cultural organizations that more abstract and general communities of interest grow. Insofar as it naturally exists in capitalism, the proletariat exists in a negative relationship to the means of production. It is defined by what it lacks, not what it has. There’s no organic identification with the broader working class to be found within it. What historically did organically emerge without intervention were narrow communities of interest like the craft unions. But these organizations exclusively served the interests of a small section of skilled laborers and pitted workers against each other. This is why Vladimir Lenin, Karl Kautsky and others held to the “merger formula.” This thesis says that socialist and class consciousness develops outside the workers’ movement.2 For merger theorists, it is the duty of Marxists to merge socialism with the workers’ movement. Lenin saw this socialist consciousness developing as an intellectual pole of attraction organized around a media outlet. This outlet would win workers over to the true analysis of the situation. He saw the role of the party as a group of professional militants who would carry out the socialist line. The party would win the masses to its line by winning the leadership of workers’ organizations. But is this really how you develop socialist consciousness?

The history of failure evidenced by the Trotskyist and Marxist-Leninist movements seems to belie this notion. Socialist consciousness emerges through the development of concrete bonds in the class struggle. It develops through a shift in collective identity among broad sections of the population. If someone is to oppose the American empire in favor of the Co-operative Commonwealth, they have to come to identify as a socialist, as a worker, and as a member of humanity, not as an American, a Democrat, or a conservative. Socialism does not demand that one gives up all their other identities; you can still be a Christian, black, queer, an environmentalist, etc. But it does demand that the identities you hold, and the communities of interest they signify, are emancipating and do not oppress others. It is the task of communist militants to embed themselves in communities of interest. We must begin the process of congealing conscious organizations for the struggle to change conditions. It’s only by organizing within the class, not above and outside it, that building a socialist movement is possible. However, it is important to recognize that identification with socialism alone is not an end but only a means to an end. In “Red Vienna,” Amsterdam, Berlin, Milan, and Paris there have been widespread socialist cultures that failed to bring about the victory of the working class. In the absence of a science of revolution, the socialist movement cannot make revolution, but in the absence of a socialist movement, the science of revolution is a dead letter.

Up-skilling and De-skilling

This, therefore, poses the question: how do we develop a science of revolution within the socialist movement? By creating a culture of comradely co-operation. By default in our society there is a culture of authoritarianism and passivity where we expect other people to give direction to our lives and do our thinking for us. Even if an ideology is ostensibly democratic, anarchist, or revolutionary in content, the practices around it are often incredibly authoritarian. This is a reality that all socialist organizations confront. But by training up of new members, giving them structured tasks that help increase their confidence, and also treating them with the utmost respect, we can enculturate our organizations into a way of acting which prefigures the Co-operative Commonwealth to come.

Respect, though, does not mean accepting any excuse for why someone hasn’t done a task; it means holding them accountable in a gentle but firm way. It means “pushing” people beyond their comfort zones. It means helping them address the things that stand in the way of realizing the goals that they believe in. Pushing, a tactic developed by unions to build solidarity, is the bedrock of creating a culture of comradely cooperation and it applies to leaders as much as rank-and-file members.

Likewise, up-skilling and education are processes that should happen constantly. By encouraging the full, well-rounded development of cadre, each member, rather than an isolated intellectual pole, can use their own faculties to reason and engage in communist politics. Up-skilling needs to recognize the interdependent nature of social labor in advanced economies. Rather than creating a movement of independent artisans who jealously guard their autonomy, communists can create a higher freedom for people to realize their goals through their willing subordination to functional discipline and the recognition of necessity.

On the Left, education almost universally takes the form of either reading classic texts in groups or having an intellectual lecture to a captive audience about the correct positions on abstract political theories. There are exceptions to this. Sometimes it takes the form of what amounts to liberal racial sensitivity training, re-framed with radical jargon. Other times a particularly enthusiastic undergraduate might ramble on about the ideas of postmodern philosophers. In fewer cases, parties or affinity groups put on practical skills-based training sessions. These might be about how to screen-print, legal rights, how to conduct a picket, security culture, and so on. In particular, the General Defense Committee of the Industrial Workers of the World provides workshops on these topics. Unfortunately, their reach is limited to the disparate, unorganized, activist community from which GDC membership is generally drawn. It is true that skills-based training in and of itself doesn’t have political content; someone can screen-print a shirt for any reason, whether it’s making money or helping a cause. However, there’s no reason that organizers must segregate political enculturation and education from skills-based training. If you are teaching people how to set up a blockade, the politics of why you use blockades is a necessary part of the training. Even with seemingly apolitical subjects like gardening, there are innumerable places where you can tie in political education. With gardening, this can take the form of talking about why capitalism creates food deserts, the unsustainable agricultural practices of major farmers (and the insufficiency of community gardens as an ultimate solution), the cultural chauvinism in the produce section of supermarkets, or the concrete politics of seed suppliers. There is no area of practical education that does not have aspects which can be politicized. That said, there is still a need for comprehensive analysis of the world and a need for engagement with abstract ideas like the economic contradictions of capitalism, the nature of the state, and so on. Yet, this education should highlight real-world examples and struggles as much as possible. It is after you have a foundation in the real meaning of class struggle that it makes sense to begin to explore higher theory, because you can relate it to the world rather than just other ideas you’ve read about.

In scientific management, the principal method of educating people in new methods is not just lecturing at them or using abstract arguments. Instead, managers use object-lessons that allow the worker to see firsthand why the new methods are superior and draw their own conclusions. Feedback and explanations are used to supplement the practical education. Taylor says:

…The really great problem involved in a change from the management of “initiative and incentive” to scientific management consists in a complete revolution in the mental attitude and the habits of all of those engaged in the management, as well of the workmen. And this change can be brought about only gradually and through the presentation of many object-lessons to the workman, which, together with the teaching which he receives, thoroughly convince him of the superiority of the new over the old way of doing the work. This change in the mental attitude of the workman imperatively demands time. It is impossible to hurry it beyond a certain speed. The writer has over and over again warned those who contemplated making this change that it was a matter, even in a simple establishment, of from two to three years, and that in some cases it requires from four to five years.

The first few changes which affect the workmen should be made exceedingly slowly, and only one workman at a time should be dealt with at the start. Until this single man has been thoroughly convinced that a great gain has come to him from the new method, no further change should be made. Then one man after another should be tactfully changed over. After passing the point at which from one-fourth to one-third of the men in the employ of the company have been changed from the old to the new, very rapid progress can be made, because at about this time there is, generally, a complete revolution in the public opinion of the whole establishment and practically all of the workmen who are working under the old system become desirous to share in the benefits which they see have been received by those working under the new plan.

An object-lesson is showing the truth of something in practice instead of theory. Originally, object-lessons were a form of education which used a visual prop to teach a concept, but they have come to mean any sort of practical illustration. For instance, when Taylor sought to introduce scientific management to the machine factory, his improvement of the output of the initial subject served as an object-lesson to the management. It proved to the foreman that his methods worked. Likewise, when Taylor introduced scientific management to pig-iron shoveling, it was having Schmidt work under the close direction of a supervisor that enabled him to see first-hand that he could do the higher rate of work just by using particular motions. For Taylor, these lessons are much stronger than theoretical discussion can be. They prove the truth of the efficacy of a method directly. Taylor believed each worker should be individually trained in this manner so that they personally develop buy-in to the methods.

The work of philosopher and educator John Dewey validated Taylor’s theory. Dewey had seen generations of students pumped out by the academy who knew science, philosophy, economics and so on abstractly, but had no idea how to apply it to the real world. To solve this problem, he began with the premise that if someone cannot make use of information in finding solutions to problems, they don’t have a meaningful understanding. From this, he concluded that the best way to give someone real knowledge was to have them solve problems themselves, with any necessary information available.3 Testing his pedagogical theories at the University of Chicago Laboratory School, Dewey showed that learning by doing is more effective than simple theoretical instruction. Some educators inspired by his work took this to mean that completely unstructured education where students problem-solve themselves was ideal, but Dewey himself pushed back on this. In his framework, students need carefully crafted object-lessons that demonstrate the principle at stake and work under careful supervision from instructors who are ready to provide abstract knowledge as students need it. Unfortunately, capital appropriated Dewey’s research and reduced it from a theory of how to instill deeper knowledge into a method of imparting narrow skills. Capitalists promote models of “learning by doing” and technical education that leave out the abstract knowledge and comprehensive vision that is essential for making narrow technical knowledge useful beyond a specific application. This logic is the same one that Taylor himself used as a means to enforce the social division of labor.

The final piece of scientific management is the system of “functional foremen.” Rather than relying on a single manager whose job it is to coordinate and motivate the workers, each area of competence is divided between several individuals whose job it is to direct the workers in their own area. By dividing up the tasks of management, Taylor was able to create a system where each part of the job of organizing labor is given someone’s full attention rather than it being left up to the motivation of the one-man manager or workers to get it done.

Under functional management, the old-fashioned single foreman is superseded by eight different men, each one of whom has his own special duties. These men, acting as the agents for the planning department, are the expert teachers, who are at all times in the shop, helping and directing the workmen. Being each one chosen for his knowledge and personal skill in his specialty, they are able to not only tell the workman what he should do, but in case of necessity they do the work themselves in the presence of the workman, so as to show him not only the best but also the quickest methods.

One of these teachers (called the inspector) sees to it that he understands the drawings and instructions for doing the work. He teaches him how to do work of the right quality; how to make it fine and exact where it should be fine, and rough and quick where accuracy is not required, — the one being just as important for success as the other. The second teacher (the gang boss) shows him how to set up the job in his machine, and teaches him to make all of his personal motions in the quickest and best way. The third (the speed boss) sees that the machine is run at the best speed and that the proper tool is used in the particular way which will enable the machine to finish its product in the shortest possible time. In addition to the assistance given by these teachers, the workman receives orders and help from four other men; from the “repair boss” as to the adjustment, cleanliness, and general care of his machine, belting, etc.; from the “time clerk,” as to everything relating to his pay and to proper written reports and returns; from the “route clerk,” as to the order in which he does his work and as to the movement of the work from one part of the shop to another; and, in case a workman gets into any trouble with any of his various bosses, the “disciplinarian” interviews him.

Co-equal members of a collective can take these roles without recourse to the social division of labor. In place of a “disciplinarian” might be an arbiter, but otherwise if you are organizing work that is complex and at a large enough scale, it makes sense to break down roles and responsibility functionally. Leadership is a burden that we should spread around as much as possible to avoid burn-out and dependency on super-organizers. While Taylor would have one individual specialize in each type of functional management, by breaking management apart it actually makes rotating responsibility much easier.

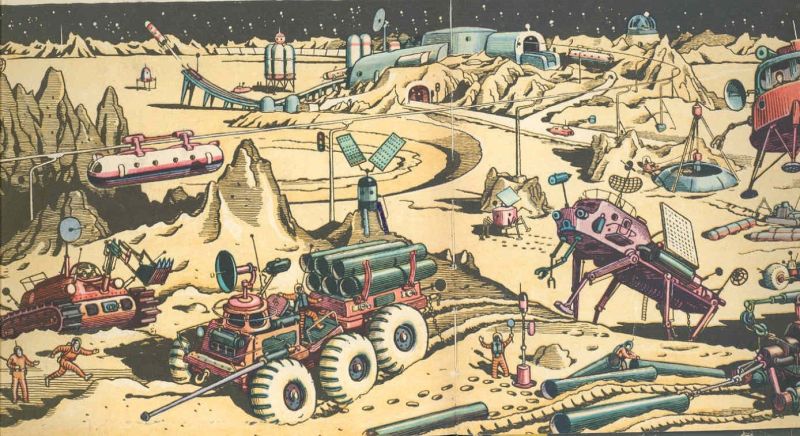

Capitalism is the New Feudalism

Our society developed the technical system that governs capitalist production by and for the logic of capital accumulation. The way we design machines is not to empower workers, but to increase productivity. The tendency of development in both production and distribution have created conditions of dependency. These asymmetries are incompatible with an emancipated society. For instance, the move toward content-streaming and away from physical media has turned consumers of content into rent-payers dependent on a service provider. This initially presented itself as a centralization in the form of Netflix replacing local video distributors. However, a plethora of rival streaming services have emerged who divvy up the pool of consumption-rents into ever-smaller fiefdoms. Likewise, within production itself, the de-skilling of workers creates more dependency on capital than if they were merely denied the means of life without working. It was plausible that a skilled tradesman could escape bondage to a master under the pre-industrial manufacturing system. After saving enough to purchase physical means of production, a tradesman could open their own shop and even hire their own apprentices. But if an unskilled worker tried this, assuming the acquisition of sufficient money to buy physical means of production, they would lack the knowledge necessary to do anything but the same menial tasks they had been employed in before. To illustrate this point, we can look to Uber and Lyft, which have begun the process of proletarianizing taxi workers. While drivers for both firms are nominally “independent contractors” (a legal position hotly contested in the courts) and own their own physical means of production in the form of their car, they are dependent on the navigational and commercial technology of the app. Even if an Uber driver knows the city they work in well, it’s unlikely that their knowledge approaches the dense working-knowledge taxi drivers possess of the streets. Likewise, while taxi drivers are usually also dependent on a dispatch company, they can develop their own network of clients, while Uber drivers are in a more precarious position. Taxi services are a classic example of a protected craft. In some cities like New York, the government directly limits how many taxis can be on the street. They use a system of “medallions” which entitle the owner to provide taxi services. In other cities, heavy regulation and education requirements prevent easy access to outsiders. Ultimately, Uber and Lyft seek to replace their drivers with fleets of autonomous vehicles, but for now they are happy to shift the costs of business onto their proletarianized workforce’s physical means of production in the form of wear and tear.

Marx misidentified the source of the power imbalance between workers and capitalists as the legal ownership of the physical means of production. In his day, productive technology seemed to exclusively take the form of tools. If Marx were right, there should be no alienation within employee-owned enterprises beyond a certain level of externally imposed labor discipline forced by the market. This is the thesis of some reformist Marxists like Richard D. Wolff. Wolff claims that worker-owned enterprises would in themselves create a genuinely democratic society.4 But employee-owned companies, like the grocery chain Winco and the Chinese phone manufacturer Huawei, are only different from traditional capitalist firms in offering stock compensation and the same kind of indirect control shareholders exert over joint-stock companies. Even if, as Wolff proposes, you have formal democracy in management, under capitalism you are still dependent on technical experts to actually run the firm. In Yugoslavia, where the Communists created a system of “self-management,” it was still technical experts who directed production.

The source of Capital’s power is the monopolization of the technical knowledge to direct production and transmute the inputs of production, including the expended lifeforce of workers, into wealth. Is it any wonder that the biggest blows in the trade war between the US and China are in the form of the US denying Chinese technology companies access to intellectual property? Capital designs the physical means of production, be they apps, looms, grocery check-out kiosks, or anything else, with dependency in mind. The legal ownership of the physical means of production is a necessary moment in the alchemical process of capital accumulation. But ownership follows from the occulting of organizational and technical knowledge. This doesn’t mean that the denial of the necessities of life to workers, ownership of physical resources, and minority control of the physical means of production are unimportant. These are features of property-societies in general, like ancient slave empires. They are not unique to capitalism. It is after the development of class divisions that society established property. What traditional Marxist analysis calls “the law of value,” the emergent logic of capital accumulation through market competition, helps create conditions of alienation and exploitation within capitalist firms, but it cannot explain the full scope of economic oppression in bourgeois society. Significant portions of the economy have insulation from market forces. Both civil and military bureaucracies exhibit many of the same features as market enterprises even as they also face other pressures. Within capitalist firms, the logic of central planning predominates. There’s little data on how much of the economy is non-market corporate activity, but over 1/3 of US international trade is intra-firm.5 In The People’s Republic of Walmart, Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski argue that much of global capitalism is already a planned economy.

While the notion that this type of planning relates to genuine socialist relations, beyond generating useful mathematical tools, is suspect, it is important for considering how much of the hell of the firm is created by logics of domination beyond that of capitalism proper. Wage-labor is only a particular form of a tributary regime in both capitalist enterprises and public bureaucracies. With the transfer of power into the hands of the working class, we will abolish the tributary system of labor. However, while socialist society will inherit the existing physical apparatus of production, it must be altered according to the principles that will govern socialist society. When capitalism formally subsumed manufacture and feudal society under the logic of value, it still used the old craft methods. Capitalism came to really subsume production when it introduced the system of economic dependency characterized by asymmetrical knowledge hierarchies and the domination of individuals by machines. Socialist society too will formally subsume the capitalist methods of production, but only by introducing the principle of comradely cooperation will it begin the process of its own real subsumption by creating the general mastery of knowledge by the working class and designing machines whose telos is to serve the laborers running them.

Whose Science?

In most cases, mastery of different areas of knowledge requires the mastery of their particular jargon. Sociobiology, communications, psychology, economics, political science, anthropology, sociology, management theory, and so on each have their own ways of talking about identical phenomena. Each approach acts as a lens for talking about social reality and organizing it intellectually. This allows us to discuss different aspects of problems. But academics segregate themselves into closed discourses, creating an impediment to intelligibility between fields and accessibility for the uninitiated. Even in academic contexts where departments encourage multidisciplinary approaches, the volume of work that an individual theorist can synthesize is a hard limit on analysis. Unless they can break down jargon, or become world-renowned, the impact of their work will be confined to one or two fields. Each department represents centuries of the application of human brainpower toward understanding and organizing our world for the benefit of the species. Workers must master the knowledge they create and make it serve the whole people if we have any hope of achieving a meaningfully free society. Departmental specialization, with its accompanying requirement of many years of indoctrination, serves to perpetuate intellectuals as a class. It robs the masses of the knowledge that is their birthright. Most people today cobble together a worldview from anecdotes, random facts, and whatever “education” the bourgeois state feels is sufficient to ready them for entry into the workforce. The process of creating a unified world science is as much the systematization of knowledge for the broad masses as it is the unification of the disparate fields of the academy. To quote Alexander Bogdanov:

Until now, although scientific philosophy appears as the property of only a few people, it nonetheless reflects in reality a level of cultural development common to all humanity. The unreflective philosophy of laypeople rules over the masses, but it corresponds merely to scraps and fragments produced by the general labour of culture, merely to the lowest steps on the ladder of social development that have already been climbed. ‘The role of scientific philosophy in the practical struggle of life’, our author says, ‘is similar to the role of a military commander who has climbed to the top of a high mountain from which the disposition of the troops of both armies and possible routes are most visible and so finds the most suitable route’. I agree. The high mountain is formed from the entire gigantic sum of attainments achieved by humanity in its collective labour-experience. For an individual person, it is a long and difficult journey to the very peak, but everyone ought to know what can be seen from there. If one only takes bits and pieces of scientific philosophy and learns them without systematically connecting them with other parts of socially accumulated experience and without monitoring them by means of a variety of socially produced techniques, then what is obtained, for all that, is a poor and unreliable ‘homemade’ philosophy.

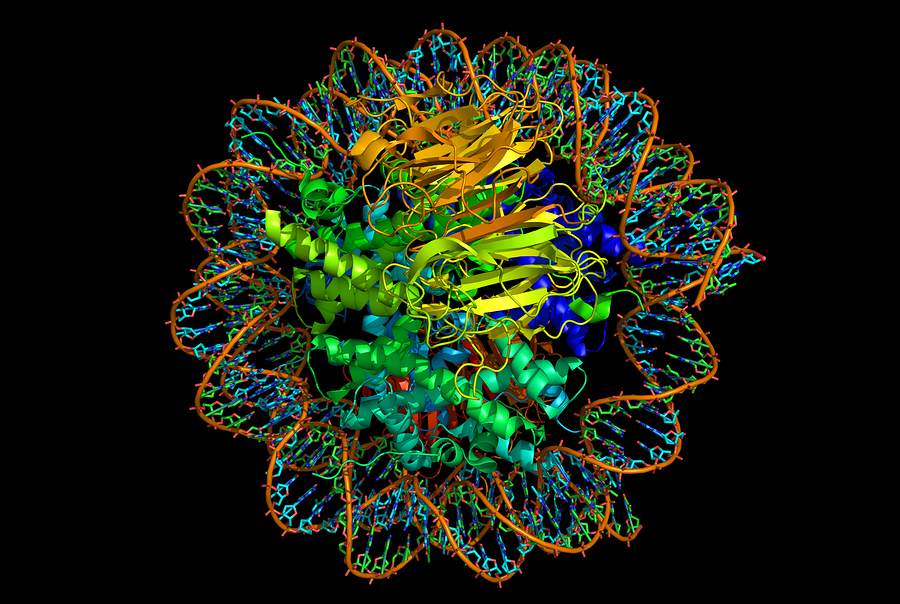

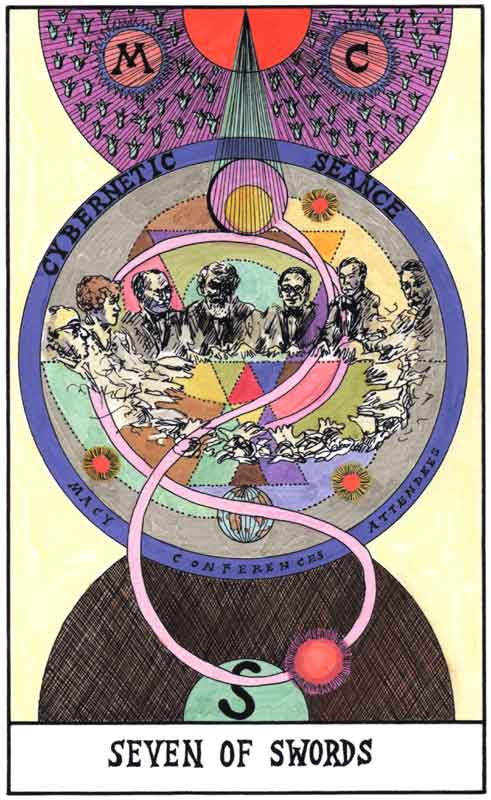

To systematize science, Bogdanov drew on Karl Marx and Richard Avenarius. Avenarius was a leading philosopher of science who, along with Ernst Mach, revolutionized epistemology. Bogdanov’s goal was to transcend the limitations of both dialectical materialism and positivism. What he created was a unified organizational science which he termed Tektology. This science was first denounced by dogmatic Hegelian philosophers like Abram Deborin and then struggled against by leading Bolshevik theorists.6 At first, the party leadership tolerated Tektology because many of the men instrumental in building the planned economy, like Vladimir Bazarov and Nikolai Valentinov, drew on it. Eventually, the Soviet authorities under Stalin ruthlessly suppressed it where under Lenin it had merely faced official censure. The regime systematically imprisoned or killed researchers and Bolsheviks who promoted Tektology in the first purges before the Trotskyists and others faced similar methods. Tektology faded from memory but the underlying principles were not lost.