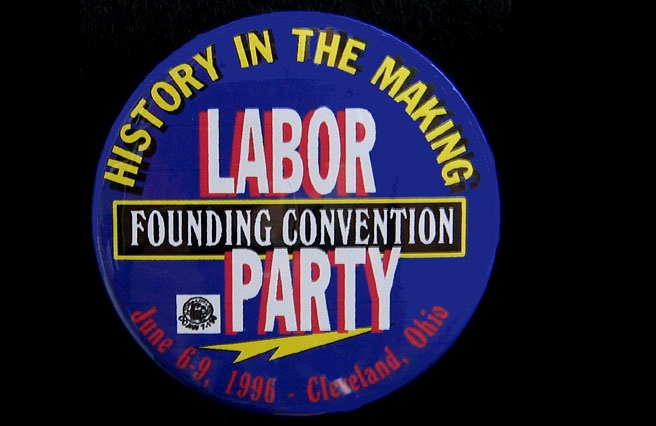

In this special edition of Cosmopod’s ongoing labor interview and history series, Remi is joined by two legends of the US socialist labor scene: Adolph Reed and Ed Bruno. Tune in for a long and enlightening discussion of the attempt at an American Labor Party in the 1990s-2000s, where we stand both as a working-class and an organized left in light of waning neoliberalism, the trendlines emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, the necessary order of priority between identity- and class-based organizing, how socialists should relate to electoral struggle, and much more.

The Practical Policy of Revolutionary Defeatism

Matthew Strupp lays out the politics of revolutionary defeatism in contrast to the approaches of third-campism and third-worldism.

In April 1964, at a luxury hotel overlooking Lake Geneva, a young Jean Ziegler, at that time a communist militant, asked Che Guevara, for whom he was serving as chauffeur, if he could come to the Congo with him as a fighter in the commandante’s upcoming guerilla campaign. Che replied, pointing at the city of Geneva, “Here is the brain of the monster. Your fight is here.”1 Che Guevara, though certainly not a first-world chauvinist, recognized the crucial role communists in the imperialist countries would have to play if the global revolutionary movement were to be successful. How then, as communists in close proximity to the brain of the monster, or in its belly, as Che is reported to have put it on another occasion, can we effectively stand against the interests of “our” imperialist governments? The answer to that question is the policy of revolutionary defeatism. This article will go over the origins and meaning of defeatism, take a look at its complexities with the help of some examples, and take up the challenge posed to it by the politics of both third-worldism and third-campism.

Origins of Defeatism

The logic of revolutionary defeatism flows from the basic Marxist premise that the proletariat is an international class, and that in order to triumph on a global scale it needs to coordinate its political struggle internationally. This means that when workers in one country are faced with actions by “their” state that pose a threat to the working class of another country, they must be loyal to their comrades abroad rather than their masters at home. Rather than be content with simple condemnations, they must also pursue an active policy against their state’s ability to victimize the members of their class in the other country. This means strike actions in strategic industries, dissemination of defeatist propaganda in the armed forces, and organizing enlisted soldiers against their officers. In the case of a particularly unpopular or difficult war, all politics tends to be reoriented around the war question, and, if the state has been destabilized by the demands of the war and the ongoing defeatist activity of the workers’ movement, this can lead to an immediate struggle for power and the possibility of proletarian victory. If no such conditions are present, the defeatist policy can serve to train the proletariat and its political movement to oppose the predatory behavior of its state and, in practical terms, blunt the business-end of imperialism and mitigate its devastating consequences for the working class abroad.

This policy of defeatism developed alongside the growth of mass-working class politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the proletarian movement grew to the point where its international policy became a live and important question. There were many positions bandied about in this period, some more or less defeatist, others placing the workers’ movement squarely behind national defense. Many individual socialists, including Marx and Engels, varied in their advocacy of one or another. An early expression of a policy of revolutionary defeatism can be seen in Engels’ 1875 letter to August Bebel, in which he criticizes the newly drafted Gotha Unification Program of the German Social-Democratic Party (SPD) for downplaying the need for international unity of the workers’ movement. Engels writes:

“…the principle that the workers’ movement is an international one is, to all intents and purposes, utterly denied in respect of the present, and this by men who, for the space of five years and under the most difficult conditions, upheld that principle in the most laudable manner. The German workers’ position in the van of the European movement rests essentially on their genuinely international attitude during the war; no other proletariat would have behaved so well. And now this principle is to be denied by them at a moment when, everywhere abroad, workers are stressing it all the more by reason of the efforts made by governments to suppress every attempt at its practical application in an organisation! And what is left of the internationalism of the workers’ movement? The dim prospect — not even of subsequent co-operation among European workers with a view to their liberation — nay, but of a future ‘international brotherhood of peoples’ — of your Peace League bourgeois ‘United States of Europe’!”2

Engels is congratulating the German workers’ movement for their internationalist behavior in war but chiding them for retreating from this internationalism in their political program. The war he is referring to is the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Marx had actually initially been German defensist in this war but changed his position after German troops went on the offensive.3 The German workers’ movement as a whole, though, mostly opposed the war in an admirable fashion, and Engels claims this was the reason for their esteem in the international movement. Not only did its political leaders condemn the war, but its organizations also carried out strikes in vital war industries in the Rhineland. This active stance of opposition to the war and active coordination of international political activity by the working class is what Engels thought was missing from this part of the Gotha Program, and he thought it was a step down from the truly international perspective of the International Workingmens’ Association. Its drafters included the vague internationalist language of the “Peace League bourgeois”, but made no mention of the practical tasks of the movement in this respect. Engels argued that the workers’ movement needed to coordinate its activities on an international scale, and that included acting in an internationalist fashion during war-time.

Nor did Engels limit his expression of a precursor to revolutionary defeatism to wars within Europe, where there was a developed working-class movement that could be destroyed in another country by an invasion from one’s own. He thought it was also applicable in matters of “colonial policy”, and that workers in imperialist countries had the political task of organized opposition to imperialist exploitation. He believed that if they failed in this task they would become political accomplices of their bourgeoisie. In an 1858 letter to Marx he wrote:

“the English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois, so that the ultimate aim of this most bourgeois of all nations would appear to be the possession, alongside the bourgeoisie, of a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois proletariat. In the case of a nation which exploits the entire world this is, of course, justified to some extent.”4

These writings of Engels’ express two important features of Lenin’s revolutionary defeatist policy in World War I and that of the Communist International after the war. Namely, the importance of active, organized efforts to hamper the ability of one’s own state to carry out the business of war and imperialism, and the applicability of the policy to both inter-imperialist wars and to colonial and semi-colonial/predatory imperialist wars.

The Second Socialist International received the first major test of its ability to pursue a defeatist policy with the onset of World War One– and it failed spectacularly. Up until that point, the German SPD, the model party of the International, had followed an admirable policy of voting down all state budgets of the German Empire in the Reichstag under the slogan “For this system, not one man and not one penny!”, as Wilhelm Liebknecht declared at the foundation of the Bismarckian Reich.5 This policy allowed the German party to think of its parliamentary activity with a lens of radical opposition, through which they saw themselves as infiltrators in the enemy camp, intent on causing as much trouble for the state and its ability to rule as possible and securing whatever measures they could to benefit the movement outside the parliament. They made use of all the procedural stops they had at their disposal along the way, and used their parliamentary immunity to decry abuses like violence against the workers’ movement and German colonial wars in ways that would otherwise be illegal, though this didn’t keep August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknect, for many years the SPD’s two representatives in the Reichstag, from being convicted of treason and imprisoned for two years for their opposition to the Franco-Prussian War, particularly for linking opposition to German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to support for the Paris Commune.6 This was not a revolutionary defeatist policy in itself and the behavior of socialists in relation to the armed forces in wartime remained untheorized, but it was an important attitude for a party of revolutionaries to adopt towards their own state and its warfighting capacity. Politicians the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) has elected in the United States, unfortunately, do not seem to see their activity in the legislature in this way and seem to think they are there more to “get things done” than to “hold things up” for the benefit of the movement. The DSA has also failed to adopt a “not one penny” position on the military budget. A resolution to do so was introduced at the 2019 convention, but was not championed by either of the main factions there.

In August 1914 the SPD’s anti-militarist discipline broke down, as many of its representatives in the Reichstag voted for German war credits and much of the movement fell in line behind the war effort. The same happened in all the other parties of the International in the belligerent countries, with the exception of Russia and Serbia. The divide between those who supported the war and those who opposed it did not follow the existing pre-war political divisions. War socialists were drawn from the right, left, and center of the International. Some made the decision on the basis of “national defense” or out of an unwillingness to become unacceptable to bourgeois politics when they were winning so many reforms for the working class, others to defend French liberty from the Kaiser, or German liberty from the Tsar, still others to defeat British finance capital’s grip on the world, or to spark a revolution, or to train the proletariat in the martial spirit for the waging of the class struggle.7 No matter how they justified it though, these socialists were all feeding the proletariat into the meat grinder of imperialist war. There were no progressive belligerents in the First World War. Categories of “aggressor” and “victim” did not apply. It was, as Lenin put it, an “imperialist war for the division and redivision” of the spoils of global exploitation.8

The immediate reaction of those in the socialist movement opposed to the war after the capitulation of so many of the national parties was to organize a series of conferences at Zimmerwald (1915), Kienthal (1916), and Stockholm (1917), to work out a socialist peace policy. At Zimmerwald there soon emerged a left, who favored a policy of class struggle against the war, essentially a revolutionary defeatist position, since carrying it out would detract from the coherence and fighting ability of the armed forces. Lenin sided with this left but said they hadn’t gone far enough, not only did a policy of class struggle against the war, or as he put it: revolutionary defeatism, need to be put forward, but socialists loyal to the international proletariat had to organize themselves separately in order to be able to carry it out.9 This struggle would be a political one, directed at the armed forces of the capitalist state and aiming for their breakup under the pressure of defeatist propaganda and fraternization between the troops of the belligerent countries. On the concrete form of this struggle Lenin wrote, in November of 1914, in The Position and Tasks of the Socialist International:

“War is no chance happening, no “sin” as is thought by Christian priests (who are no whit behind the opportunists in preaching patriotism, humanity and peace), but an inevitable stage of capitalism, just as legitimate a form of the capitalist way of life as peace is. Present-day war is a people’s war. What follows from this truth is not that we must swim with the “popular” current of chauvinism, but that the class contradictions dividing the nations continue to exist in wartime and manifest themselves in conditions of war. Refusal to serve with the forces, anti-war strikes, etc., are sheer nonsense, the miserable and cowardly dream of an unarmed struggle against the armed bourgeoisie, vain yearning for the destruction of capitalism without a desperate civil war or a series of wars. It is the duty of every socialist to conduct propaganda of the class struggle, in the army as well; work directed towards turning a war of the nations into civil war is the only socialist activity in the era of an imperialist armed conflict of the bourgeoisie of all nations.”10

Lenin did not think that the adoption of a revolutionary defeatist position by communists in the imperialist countries was only applicable to the specific conditions of World War I, where the conflict was reactionary on all sides and the proletariat had well developed political organizations in all the belligerent countries who could turn the struggle against the war into an immediate struggle for power. In response to the objection of the Italian socialist leader Serrati to a resolution proposed by the Zimmerwald left that advocated a class struggle against the war, that such a resolution would be moot because the war was likely to end quickly, Lenin said: “I do not agree with Serrati that the resolution will appear either too early or too late. After this war, other, mainly colonial, wars will be waged. Unless the proletariat turns off the social-imperialist way, proletarian solidarity will be completely destroyed; that is why we must determine common tactics.”11 Here, the revolutionary defeatist policy is not simply a path to the immediate struggle for power, as it indeed was in the case of WWI, rather it’s related to the adoption of a particular attitude to the activities of one’s own state in general. For communists in the imperialist countries, this means fighting against the wars your country wages to maintain its grip over its colonies and semi-colonies, using the same tactics you would use in the case of a “dual defeatism” scenario, where communists in all the belligerent countries are defeatist in relation to their country’s war effort, in an inter-imperialist war that is reactionary on all sides.

However, these two scenarios should not be confused. Although Lenin claimed the policy pursued in response to one should be put forward in the case of the other, this should not be extended to the communists in the oppressed country. There is no question of being “defeatist” in relation to a progressive war for national liberation. The Communist International made this clear in condition 8 of its 21 conditions for affiliation:

“Parties in countries whose bourgeoisie possess colonies and oppress other nations must pursue a most well-defined and clear-cut policy in respect of colonies and oppressed nations. Any party wishing to join the Third International must ruthlessly expose the colonial machinations of the imperialists of its “own” country, must support—in deed, not merely in word—every colonial liberation movement, demand the expulsion of its compatriot imperialists from the colonies, inculcate in the hearts of the workers of its own country an attitude of true brotherhood with the working population of the colonies and the oppressed nations, and conduct systematic agitation among the armed forces against all oppression of the colonial peoples.”12

The important point here is that revolutionary defeatism in a predatory imperialist war is only a prescription for communists and proletarian movements in the imperialist countries. Today this means those that benefit from a flow of value coming from global wage arbitrage and the super-exploitation of newly proletarianized former peasants in the former colonial and semi-colonial world. In such a war, the question of defeatism or defensism in the oppressed countries, in the realm of practical policy, is precisely a question for communists in the oppressed countries themselves. This question should be decided on the basis of how best to serve the ends of national liberation and social revolution, taking the particular national political conditions and those of the war into account, but the victory of the oppressed country should be favored over that of the imperialist country.

The Communist International itself may actually have gone too far in the direction of defensism, not in the sense of favoring the victory of the oppressed country, which should always be the case, but in the sense of the relationship of communists in the oppressed countries to their state and to other political forces. Its policy of the anti-imperialist united front was ambiguously formulated and its implementation often involved subordinating the communist parties to the bourgeois nationalist movements. The most notorious example being the case of China, where Comintern directives on the Communist Party’s relationship to the Kuomintang had to be explicitly rejected by Mao and his co-thinkers for the Chinese Revolution to triumph.13 This logic has been taken to the extreme in recent years by the Spartacist League, a far-left sect that has devoted space in their paper to putting forward a position of military support for ISIS: “We take a military side with ISIS when it targets the imperialists and forces acting as their proxies, including the Baghdad government and the Shi’ite militias as well as the Kurdish pesh merga forces in Northern Iraq and the Syrian Kurdish nationalists.”14 The cases of China and modern Iraq and Syria show that sometimes in cases of internal disorder or when the forces “resisting the imperialists” are particularly reactionary, whether the Kuomintang or ISIS, the best option for communists and the anti-imperialist struggle is for communists in the oppressed country to wage a military struggle against both the imperialists and the reactionary forces “resisting” them.

Vietnam

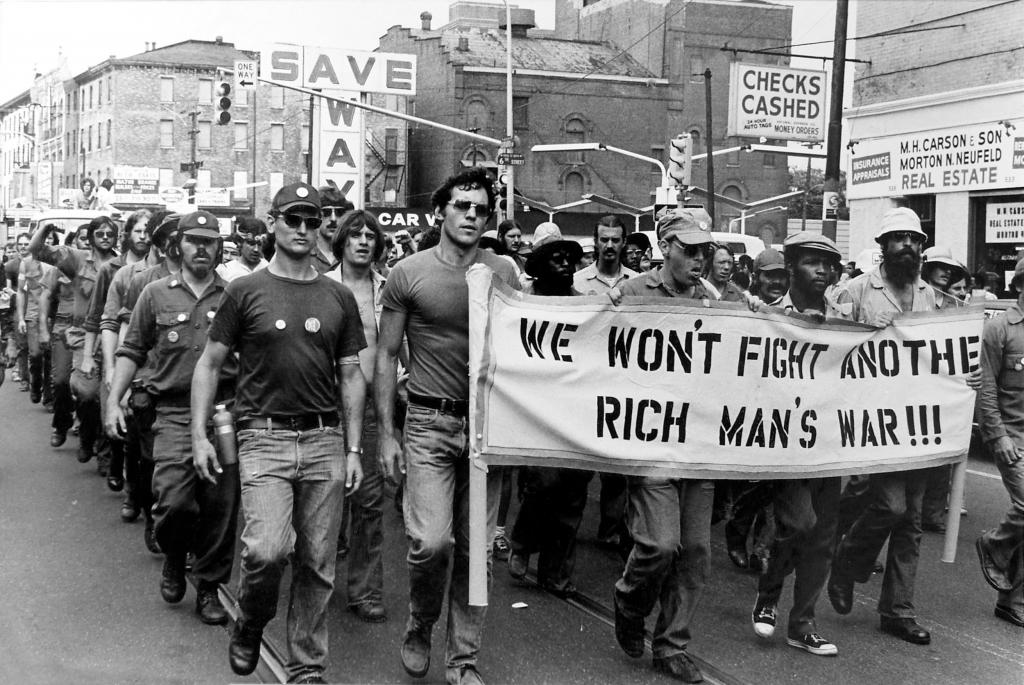

The most successful application of revolutionary defeatist tactics in the US was in the case of the Vietnam war. The best-known images of the anti-war movement in the US are of large public marches and of police repression on college campuses. The truth is that these things were actually pretty ineffective at producing a US defeat and withdrawal. Large demonstrations can do something to turn public opinion against the war and college students were able to take some actions that made a meaningful difference by taking advantage of their positions in a crucial part of the war machine: the university; but these things were not enough to halt the functioning of the most destructive imperialist military in history. We can verify this by comparing the movement against the war in Vietnam with that against the war in Iraq. As with Vietnam, the Iraq war was opposed by millions of demonstrators, including by between 6 and 11 million people on a single day, February 15, 2003, the largest single-day protest in world history; yet the war kept going.15

What was the difference in Vietnam? The answer lies both in the brilliant military strategy of the Vietnamese liberation movement under the leadership of the Communist Party, and in the practical application of a revolutionary defeatist policy by sections of the US far-left and workers’ movement. This meant disrupting the recruitment of the US armed forces, and especially, organizing opposition within the military itself. This resulted in a situation where “search-and-evade” tactics became the ordinary state of affairs for many units, as common soldiers deliberately avoided combat or simulated the appearance and sounds of combat to deceive their officers, over 600 soldiers carried out “fraggings”, murders or attempted murders of their officers, often with frag grenades, and groups of soldiers occasionally carried out organized mutinies. By June 1971 this state of widespread organized resistance to the war led military historian Colonel Robert D. Heinl to write an article titled The Collapse of the Armed Forces, in which he claimed that “The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States.”16 This was undeniably a key factor in the breakdown of US warfighting ability in Vietnam and the eventual US withdrawal.

Some insist that the example of war resisters in the US military during the occupation of Vietnam, and by extension, the entire premise of a policy of active revolutionary defeatism, is entirely useless to today’s revolutionary movement because the nature of the US military has been entirely transformed by the transition to an all-volunteer force in the late-70’s and 80’s. What this position misses is the extent to which the claim that the US military is an all-volunteer force is itself an ideological artifice crafted by the US military establishment and the degree to which poverty itself still acts as a draft. The US military does not make public information on the income-levels or class positions of the families from which it recruits, only their geographic distribution. The fact that the localities that enlistees are drawn from are more affluent than average does not rule out that the enlistees themselves may be poor. The higher cost of living in these areas may in fact be an additional stimulus to enlistment, and the fact that military recruiters regularly use material incentives, like the promise of a free education, to prey on working-class kids, is no secret. This means that the class divide in the armed forces has not entirely been eliminated, that officers’ interests still conflict with those of enlistees, and that the possibility of mass war resistance from within the ranks of the armed forces, especially as part of a coordinated working-class struggle against imperialist war, still lies within reach.

Iran and Third-Campism

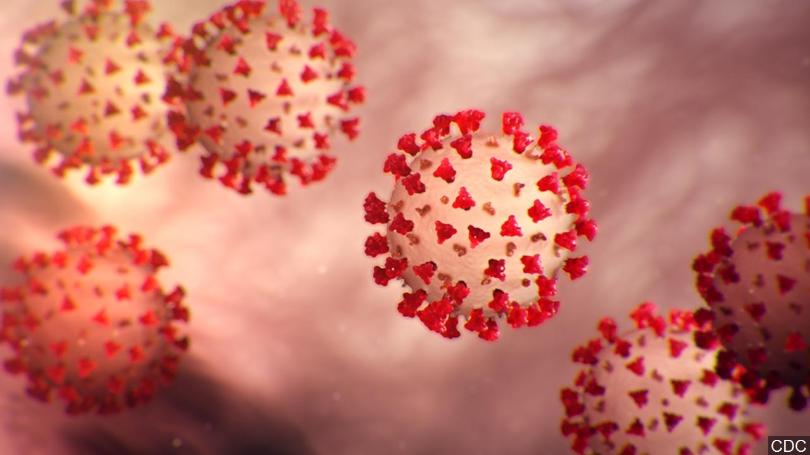

With the assassination at the beginning of this year of high ranking Iranian general Qassim Soleimani at the hands of the United States, the prospect of war with Iran became a very real possibility. In fact, a section of the US foreign policy establishment has been hellbent on bombing or invading Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that established the current Iranian regime, and the US has imposed harsh sanctions on Iran that themselves amount to a form of warfare. These sanctions have no doubt contributed to the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran, which has killed 988 and infected over 16,000, roughly 9 in 10 cases in the Middle East.17 Although the immediate worry about an invasion has died down since January, it’s still important for communists to work out what their response to such an invasion would be, because the threat remains on the table.

The main question is whether a revolutionary defeatist policy in relation to a war with Iran should be pursued or whether a Third-Campist position of “Neither Washington nor Tehran” ought to be put forward. The idea of Third-Campism, in this case, is that the political regimes of the United States and of Iran are both so reactionary that the proletariat has no stake in either side’s victory or defeat in the war and should, therefore, neither support nor actively oppose its prosecution by the imperialists. This approach is flawed. If we were considering a war between two imperialist countries on equal standing, both with reactionary governments, what this leaves out is the benefit that the proletariat in both the belligerent countries could gain by an active pursuit of a revolutionary defeatist policy. Either, it could open up the road to the seizure of power by the proletariat in one or both belligerent countries or it could only serve to train the proletarian movement in each country in the art of carrying out a struggle against “its own” state.

However, in the case of a US attack on Iran, this “soft Third-Campist” position of dual defeatism, like that implied by the left-communist International Communist Current, when it describes the Middle East after the Soleimani assassination as “dominated by [an] imperialist free for all” would also be wrong because it regards both the United States and Iran as imperialist.18 Such a war would not be reactionary and imperialist on both sides, a reactionary war by the US for the reconquest of one of its semi-colonies. It is no coincidence that the US only became hostile to the Iranian government after the ouster of its puppet the Shah, meaning that the Iranian war effort would contain elements of a progressive national liberation struggle. In the case of a US invasion, the main enemy for Iranians is not at home, their main enemy is imperialism. Communists in Iran are, of course, opposed to the political regime of the Islamic Republic for its brutal suppression of the workers’ movement and its political organizations, its regressive stance on women’s rights, and its treatment of national minorities, but they do not think it fights too vigorously against US imperialism.19 Communists in the United States should take the position: “better the defeat of US troops than their victory”, and their task would be to carry out an active policy of revolutionary defeatism against an invasion of Iran. The task of communists in Iran would be to fight off the imperialist invaders by any means necessary, including by opposing any effort by the Iranian government to disarm the Iranian proletariat as it prepares itself to resist an invasion.

Third-Worldism

There is another political strand that downplays the importance of active revolutionary defeatist politics in the imperialist countries: Third-Worldism. In this case, it is not the desirability of the proletariat in the imperialist countries carrying out a revolutionary defeatist policy that is questioned, but its political inclination to do so. All this leaves us with is joystick or sideline politics, the cheering on of great revolutionaries and great revolutionary movements, but always happening somewhere else. This makes Third-Worldism a self-fulfilling prophecy, the denial of the ability of the proletariat in the imperialist countries to challenge the imperialist bourgeoisie which exploits both them (usually rationalized by saying that proletarians in the imperialist countries are equally exploiters) and their comrade workers around the world, becomes a reason not to organize to do so. Of course a fraction of the super-profits of imperialism is sometimes distributed to workers in the imperialist countries with the aim of purchasing their loyalty to the bourgeois state. Our point is to build a movement capable of credibly offering something better than that: communism.

The idea that politics flows directly from the movement of money is an economist error, if it were true, all communist politics would be pointless, because that factor will never be in our favor. Rather, international working-class consciousness will necessarily be a subjective product of common struggle, including the anti-imperialist struggle. It is likely, as Trotsky argues in his History of the Russian Revolution, that for reasons of combined and uneven development, the world revolution will be sparked in the oppressed countries first, but that process will not ultimately be successful if revolution does not come to the imperialist countries as well.20 Most great Third-World revolutionaries have been clear about this, Che certainly was. Indeed, as the late Egyptian communist, Samir Amin wrote in Imperialism and Unequal Development:

“…Third-Worldism is strictly a European phenomenon [we may say a phenomenon of the imperialist countries]. Its proponents seize upon literary expressions, such as ‘the East wind will prevail over the West wind’ or ‘the storm centers,’ to justify the impossibility of struggle for socialism in the West, rather than grasping the fact that the necessary struggle for socialism passes, in the West, also by way of anti-imperialist struggle in Western society itself… But in no case was Third-Worldism a movement of the Third-World or in the Third-World.”21

Third-Worldism began as an optimistic reaction to successful national liberation struggles in the oppressed countries in the mid-20th century, but to the extent that it exists today, it is simply a symptom of our defeat. Third-Worldism may produce amusing artefacts like That Hate Amerikkka Beat, but it offers nothing to the practical struggle for global proletarian revolution because it refuses to even consider what might need to be done to make revolution in the imperialist countries. None of this is to discount the work of communists in the Third-World, who are doing their part in fighting imperialism and their bourgeoisie. The problem with Third-Worldism is that it’s a poor form of solidarity that looks not to the ways in which one can most practically ensure the final triumph of those one is in solidarity with.

The Upcoming Battle

The goal of communists in the imperialist countries should be to create, to quote once again Che Guevara, “two, three… many Vietnams”22, not in the sense Che used it, focoistic guerilla campaigns, but in the sense of successful applications of the revolutionary defeatist policy of class struggle against imperialist war, which killed the US military’s ability to maintain the occupation of that country. This means, in the case of unprogressive war, strikes in war industries, spreading defeatist propaganda in the armed forces, and organizing common soldiers against their officers and the war effort. We must also fight for a truly democratic-republican military policy in peacetime, rejecting foreign intervention by the United States and fighting for the universal arming and military training of the people and the right to freely organize in militias for the proletariat, as well as freedom of speech and association for the ranks of the present-day armed forces. “War is the continuation of politics by other means”23 and now is a time of relative peace, a time for politics, a time to build up our forces, to train them to become a honed weapon of class struggle, and “not to fritter away this daily increasing shock force in vanguard skirmishes.”24 But a time of war is coming, and we must have those “other means” at our disposal, we must be prepared to crush our enemies and to use the destructive and atrocious wars conjured up by the bourgeoisie as opportunities to turn the imperialist war into a civil war, to make war on the ruling class as a road to the seizure of power by the proletariat and the triumph of communism.

The End of the End of History: COVID-19 and 21st Century Fascism

Debs Bruno and Medway Baker lay out the conditions of the current crisis, the political potentials it opens up, and the need for a socialist program to pave a path forward.

As COVID-19 rages through the shell of a global civilization systematically ravaged by five decades of catabolic capitalism, the facades of processual stability are crumbling and revealing, in their place, a crossroads for human society. The illusion of stability and robustness projected upon the delicate systems of production, distribution, exchange, and social reproduction has long been predicted to evaporate. Yet the prophets of this revelation have long been marginal– considered doomsday prophesiers and malingering malcontents besotted by their own unpopular utopian aspirations. Now, in the wake of a challenge to those processes’ perpetuation – a challenge unprecedented in the annals of fully-developed, advanced global capitalism – such grim prognostications are being rewoven, this time into the weft of history.

The tasks of socialists, spectating from within the structure as it has been stripped down to the girding beams and beyond, are to clear-headedly analyze the conjuncture at which we find ourselves, identify the opportunities and dangers that conjuncture creates, and to organize at the weak points which yield the greatest leverage for reusing the rubble that results. The first part of this charge promises us a head-spinning voyage. Almost nobody alive has experienced a societal crisis of this scale, and absolutely nobody alive has experienced a menace of this nature. Furthermore, the suite of contingencies within which this havoc has arisen and within which it is doing its work have never before existed.

The imperial core has, in the course of realizing its ineluctable tendencies, hollowed itself of the substance of its self-perpetuation. The production networks have exogenized themselves, expanding for their continued competitiveness beyond the outer membrane of the core itself and relocating in territories still fertile for exploitation. On the foundation of world destruction following the Second World War, capital has created a global network of energy and resource flows, sending the production of value and the extraction of resources to postcolonial and economically colonized nations in the Global South and the periphery broadly. In the core Western nations, coronated by the whorls of history as the center of this global web, the increasingly costly machinery of capital production has been either left to rot or cannibalized in favor of an ethereal finance economy. The tools of leverage and speculation are used to direct the operation of the global system as a whole while little of substance is produced in the formerly unrivaled center of commodity production. This, however, creates a contradiction. Absent the productive and social apparatus which put the core in this privileged position, the nerve center of global capital has stripped its muscle and hollowed the bone. The aberrant wealth and power resulting from the annihilation of the two imperialist wars of the 20th century have evaporated, and a crisis of reproduction– ecological, political, cultural, and economic– has matured.

The foundering of profitability, meanwhile, has required the abortion of such regulatory mechanisms as had previously placed a limit on self-destruction, leaving the interior composition of the capitalist core bound, sedated, and ripe for predation. The exportation of ecocide, genocide, and the iron-heeled boot have become impossible; there are no boundaries in interpenetrated systems, and the segmentation once feasible has given way to self-reinforcing, malign cycles of crisis in infrastructure, geopolitics, social degradation, and ecological death.

The political systems of the core’s constituent nation-states have responded accordingly, as the coalition of interested groups inherited from the Fordist Bretton-Woods system has steadily seen its legitimacy and ability to navigate exigencies eroded. In place of the ironclad sovereignty this coalition once enjoyed, chasms have yawned– and nature abhors a vacuum. Into this void have rushed various strains of reaction, most retrograde, whether from the right or the left. In a way, the current presidential contest in the United States represents a popularity contest between various past eras to which to return: Trump wants a return to the post-historical jouissance (or doldrum-plagued interregnum, depending on whom you ask) of a mythical 1990s; Sanders to the New Deal-inflected, postwar imperial sugar-high that reigned during the 1950s and 60s class compromise; Biden to the last-ditch resuscitation of the Third Way characteristic of the late 2000s; and Marianne Williamson to the Zoroastrian golden age of 1500BCE. None of these alternatives are viable, as the preconditions for their existence no longer exist. But some of them represent the extremely powerful but heretofore latent rejection of the absurdly non-functional status quo, while the rest do not.

Many of us had hoped to have at least the ten remaining years promised us to avert certain climate catastrophe as a political deadline, and some had projected relative stability further into the future. Socialists within or adjacent to the Sanders campaign and its attendant parapolitical formations had hoped that a demonstration of its inability to implement its program would further the radicalization and cohesion of a left mass politics. This was a form of impossibilism, it has been argued, but one which could conceivably have worked along the lines it promised. The handlers of the neoliberal consensus had hoped that an exposition of the (clutch pearls now) utter incivility of the perfunctory right-populism of the Trump orbit would enable them to slowly reorient the official political sphere back into carefully-managed, popularly unaccountable, and technocratic halcyon typified by the Obama years. Neither of these alternatives are any longer possible, and the mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic points to the deeper systemic reason why, illuminating with it our overdetermined spiral into the event horizon of total catastrophe.

The structural impossibility of an effective response to the economic crash of 2007-8 made it inevitable that a more deeply impactful repetition of that crisis would manifest within the normal course of the capitalist business cycle. The overextension and simultaneous neutralization of fiscal and monetary measures introduced to reinflate doomed financial mechanisms and speculation has additionally made certain that the next capital-elimination event would be largely intractable to the top-down treatments required to sustain neoliberal suspension of profit-rate decline. In sum, we knew that another, more system-shattering crisis was coming and that it was coming soon. We could not know what event would precipitate it nor even foggily apprehend what the result would be. It is very possible that we now know the first. What we must do now is to address the second.

Intimations as to the sorts of social and political reactions to this crisis are beginning to coalesce. In recent days, the social-democratic proposal for the maintenance of the slowly disintegrating capitalist system having been roundly rejected, two main strains of response have surfaced. The first of these is a cataclysmic abdication of the concept of governance and even of society as an organ. This is best embodied in the United Kingdom’s policy of pursuing what is misnamed “herd immunity”. Actual herd immunity is not the purpose or result of this strategy. Instead, what it proposes is inaction. While the United States has de facto gone the same route due to incompetence and the total absence of social infrastructure, Boris Johnson has affirmatively asserted that the UK’s response will be to not respond. This will, as everybody knows, result in the expiration of approximately 3% of British people and the utter disintegration of the British economy, but, in Johnson’s theory, will then produce returned stability after everyone who could die from this virus has done so. Perhaps he views the lives lost along the way as more extirpation than expiration.

The Johnson approach is consonant with that of the United States and, oddly, Sweden. The key difference is that, while the central political figures in the US are surely indifferent to the eventuality spelled out above, they are at least feigning interest in taking tepid steps toward mitigating the catastrophic effects of that approach. Proposals from such figures include the following: from Trump, lying about having already accomplished the initial stages of a pandemic response; from Joe Biden, providing limited financial assistance to healthcare providers and public health organizations for the duration of the first wave of infections, thereby allowing otherwise helpless populations to access treatment; from Bernie Sanders, the same universal healthcare proposal he has advocated for decades; and from Nancy Pelosi, et al., provision of two weeks’ paid sick leave for about 20% of American workers. This constitutes a less-than-total abdication of governmental responsibility– with just enough prevarication to ensure that levels of hatred for the US stay steady but do not increase.

More interestingly, however, is the second strain of political response to the many-sided crisis precipitating around COVID-19. This strain is one that has been developing potentiality for many years, but which has, until very recently, remained embryonic and subterranean. Slavoj Zizek recently assessed the political situation in the United States as increasingly four-faceted. His categories fell roughly along the lines of neoliberal-establishment, neo-conservative establishment, right-populist, and left-populist. There are valid objections to this framing, but in the interest of this analysis, we can retain the idea that, despite appearances, the political polarity is between neoliberal-neoconservatism, straining mightily to maintain its stranglehold on the formal-political, and rupture-seeking populisms on the left and the right. Zizek’s analysis suffers from diffraction: there are not four faces, but two. There exists a backward-looking political contingent, comprising the cores of both major parties. And there is a rapidly-condensing sentiment which is formulating from the far right a politics which, in the United States, at least, is entirely new. If we accept the notion that politics is only politics in the millions, there is no forward-looking left.

The left-ruptural cohort has yet to promulgate a political vision which supersedes what it has already tried: a politics it has never stopped fighting to implement in the course of US labor history. The right-ruptural faction, on the other hand, appears to have formulated something novel and unspeakably dangerous. The mere appearance of an articulation seeking an alternative rather than a facially-improved continuation of the present arrangements is revolutionary in the post-neoliberal moment. And, as in all revolutionary epochs, the possibility for seizing the vlast – for challenging the sovereignty of the present regime and seizing it for one’s own political project – flows to the right as well as to the left. It is evident that the political center has almost fully fallen away and that a new center of gravity which will frame a new political polarity is inevitably on its way. The neoliberal hell-halcyon is as good as dead. The question that remains to us is what new social conjuncture will follow it.

The gravest threat, therefore, is neither (as most readers will agree) Donald Trump or “Trumpism”, as the liberals bray, nor the Democratic Party inertia-machines. Nor is it mass catatonia, although that threat and its ecological implications rank higher than either of the two former monstrosities. Instead, the true nightmare scenario against which we must be vigilant and organized is presented by what we have called the “Carlson Effect”. Sensing, as anyone with cortical function probably has, that the winds are shifting, elements of the American right (parallel to various European right parties and populations) have at least rhetorically embraced a vigorous right-populism tending, even, to social-fascism. At the time of writing, there have been at least three calls from prominent figures in or adjacent to the Republican Party for social provision to those deemed to be “real Americans”. Mitt Romney, the billionaire Mormon, ex-presidential candidate, and longtime denizen of the lounges of Republican Party officialdom, last week called for a $1,000 payment to offset the financial ruin in store for half of US workers in wake of the indefinite suspension of their employment. Crypto-fascist Senator Tom Cotton today decried the ersatz and indirect system of tax credits used for social provision, calling instead for a similar UBI-esque policy.

While, at first glance, these programs appear to be much-needed and overdue relief for millions of Americans barely clinging to the economic margins, they are very likely the opening shots in a coming salvo of right-populist political sentiment. A salvo which will certainly vouchsafe the irrelevancy of any left movement – and maybe even violently suppress such a movement – for generations. Of course, we would never take a position counter to the material alleviation of the suffering of the working class over insignificant political quibbles regarding who is providing that relief. The objection, however, that we should raise to this politics is not insignificant quibbling.

Any program of social provision implemented by the virulently nativist, white supremacist US ruling class or their political lickspittles will contain within it exclusionary mechanisms that will demarcate the populations they wish to recruit to their politics. Communities most affected by the grindstone of capitalist destruction will inevitably fall shy of program requirements. They may lack sufficient citizenship status or be in debt to the Internal Revenue Service. They may have criminal records or (god forbid!) low credit scores. As the Democratic Party – never a champion of the working class despite over a century of too-clever-by-half attempts to subvert it from within – has withdrawn its constituency to the extent that it now solely serves the whims and aesthetics of a shrinking, cosseted coastal elite, the space for any collectivism has gone unfilled. This will not persist as the existing pressures intensify and new ones arise. Reform movements led or won by social-democrats do not carry us further from revolution and the emancipatory project. Reform movements helmed by fascists certainly do.

The goals of any politics which falls under the scattershot term “fascist” are bounded by the class nature of their constituent population segments. Fascism, in its minimum identifying features, is a socio-political movement that hijacks an existing mass-political framework or creates an ersatz mass-political appeal in service of the perpetuation of the current class relations. Fascism arises in times of capitalist crisis; they are socio-political responses to the possibility of revolutionary upheaval. They seek to curtail this possibility by forging unitary social institutions, crushing any deviant or dissenting factors, and accommodating the reintensified cannibalization of the social fabric and its extrinsic environment, both ecological and geopolitical.

The insufficiency and brutality of the US sociopolitical system was enough to spark in its populace anger, despair, non-participation, and social disease. Its collapse will generate a deconstruction of the former system’s constituent parts and their reassemblage into something new, which, as in all ruptural processes, will come into existence as a chimera of those parts and will gradually metamorphose into something entirely new. In a society based fundamentally on settler genocide, racialized caste relations up to and including race-based slavery, aggressively-pursued imperialism, and thoroughly insinuated anti-collectivism, that recombination is very likely to yield an atrociously destructive lusus nature.1

A peculiar manifestation of this kind of settler right-wing populism took shape in Western Canada during the Great Depression. This movement called itself “Social Credit”, after the economic theories of British engineer CH Douglas, although it rapidly took on a life of its own, separate from Douglas’s original formulations. Informally led by the deeply religious educator and radio show host William Aberhart, the movement rapidly acquired a grassroots base among the impoverished farmers of Alberta during the early 1930s, and swept Aberhart to electoral victory in 1935, heralding a virtual one-party rule in the province for the following 36 years.

Although Douglas’s economic theories are not particularly relevant for our purposes, it is useful to elucidate his philosophy, particularly his conception of “cultural heritage”, which, he said, entitled citizens to dividends based on their participation in society—essentially, an early form of universal basic income. In his own words:

“In place of the relation of the individual to the nation being that of a taxpayer it is easily seen to be that of a shareholder. Instead of paying for the doubtful privilege of being entitled to a particular brand of passport, its possession entitles him to draw a dividend, certain, and probably increasing, from the past and present efforts of the community [i.e., nation] of which he is a member…. Not being dependent upon a wage or salary for subsistence, he is under no necessity to suppress his individuality”.2

Douglas himself never intended to inspire a populist movement; he rather wished simply to influence economic policy through dialogue with the powers that be.3 It was Aberhart who brought social credit to the masses. Aberhart was quite literally a rabble-rousing preacher, spreading the word of God and social credit, denouncing the establishment politicians and finance capitalists, and promising his constituents a miraculous cure to the Depression. His radio audience ballooned as the economic crisis deepened, and his conviction inspired thousands to believe in him and his cause.

The specific financial measures he proposed were not so important as the message he propounded: There is no reason for our poverty! The bankers are robbing us! We, the people who work this land, must take what is rightfully ours! Douglas himself noted that

“it would not be possible to claim that at any time the technical basis of Social Credit propaganda was understood by [Aberhart], and, in fact, his own writings upon the subject are defective both in theory and in practicability…. [However,] it was at no time Mr. Aberhart’s economics which brought him to power, but rather his vivid presentation of the general lunacy responsible for the grinding poverty so common in a Province of abounding riches, superimposed upon his peculiar theological reputation.”4

Aberhart, in line with Douglas’s own theories, proposed that the state apparatus was in the hands of bankers who cared only about their own profits, not the common people. Although he attempted to convince the political establishment in Alberta of social credit policies, he was rebuffed, so he went to the people. Through his radio show, he tapped into the alienation of the impoverished workers and farmers of Alberta, their anger at the banks which drove them into eternal debt, their despair at the neverending Depression. He denounced, too, the mainstream media, the newspapers, for their failure to publish “the truth about the financial racketeers.”5 He framed himself as a man of the people, bringing the truth to the masses which the elites concealed from them. This scenario will be familiar to many of us today, in the age of television talk show hosts who seem to be displacing serious journalism in the popular consciousness.

Aberhart insisted that social credit would never involve confiscations of property, and that “production for use does not necessitate the public ownership of the instruments of production.”6 The explicit aim of social credit was an agreement between social classes, in which all citizens (i.e. members of the national community) would be taken care of. Aberhart explicitly counterposed class struggle to the “brotherhood of man”.7 “If we do not change the basis of the present system,” he exclaimed, “we may see revolution and bloodshed.”8 It was through “the common people stick[ing] together” that class warfare and violent revolution would be averted. 9

Indeed, while the labor movement was on the rise in other parts of the country, and the social-democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, now the NDP) was making gains in the neighboring province of Saskatchewan, the left was utterly crushed in Alberta, which remains a right-wing stronghold to this day despite the death of the Social Credit Party. The victory of right-wing populism in Alberta destroyed the capacity of labor activists and socialists to have any success for generations. In uniting the workers and petty bourgeoisie against the banks and the political establishment, social credit simultaneously staved off the threat of a genuine workers’ movement which could pursue its own, independent interests.

A comprehensive history of Social Credit rule in Alberta is well beyond our scope, but it is useful to highlight one incident which occurred under Aberhart’s Premiership, which involved government officials calling for the “extermination” of political opponents, termed “Bankers’ Toadies”. The leaflet they distributed read:

“My child, you should NEVER say hard or unkind things about Bankers’ Toadies. God made Bankers’ Toadies, just as He made snakes, slugs, snails and other creepy-crawly, treacherous and poisonous things. NEVER therefore, abuse them—just exterminate them!”10

This incident epitomises the type of threat presented by right-wing populism. While liberalism openly detests the masses and pretends at enlightened nonviolence while enacting the violence of the state, right-wing populists are unafraid to whip up popular sentiment against political opposition. This is the language of pogromists.

Although Aberhart was committed to realizing his program through constitutional means, the social credit movement did not remain committed to democratic principles. The right-wing thinks nothing of using force to crush dissent. If they are willing to take coercive and even violent measures against the capitalists to enact their program, the measures they are willing to use against workers are a thousand times worse. We must give the populist right the same treatment they would visit on us: we must exterminate them.

Regardless of what exigencies arise in the coming years’ political landscape, most of which are entirely obscured to us now, we can be certain of the crux of every political question: ecological collapse. Beyond the most obvious horror of this central question, the high-visibility catastrophes which will increase in magnitude and frequency, the tendrils of crisis will reach outward into every level of our social systems. Drought will spark agricultural collapse, which will cause multiple deluges of human migration, often all at once. Severe storms, flooding, weather-pattern changes, and sea-level rise will render major metropolitan areas functionally uninhabitable. The desertification of regions now devoted to large-scale monoculture or husbandry will disrupt critical commodity chains. This will doubtless cause armed conflict within and between nations.

We have likely all read these and many other dire projections and do not need to systematically enumerate them in order to demonstrate that whatever new mode of social organization coheres from the ashes of the old, it will be structured first and foremost by ecological catastrophe. This means, however, that during the collapse or slow disintegration of this social formation, a revolutionary program of clarity, urgency, and mass appeal never before attainable is possible to pursue.

Climate change is the skeleton key that unlocks the barred gate between us and the better world we struggle for. Every demand we now pursue in the interest of social justice, proletarian self-activation, and relief of sheer human misery will become a critical factor of our social system which has to be radically transformed in order to mitigate climate collapse. This means that any progressive, affirmative program of socio-ecological collapse constitutes, by the very nature of the adaptations required, a minimum program– a suite of demands which, when implemented, create the dictatorship of the proletariat and bring into the world real democracy for the first time. All other potential courses of action responsive to the general crisis coming down the pike are not only reactive and politically reactionary but will be insufficient to the scale of the calamity they respond to. The disastrous, sublime, terrifying situation we are now faced with lays down the gauntlet: we must either overcome our inhumanity and for the first time realize our collective potential, or consign the project of humanity to ignominy and extinction.

The retooling of society has already begun But we are in the premonitory tremors, so we cannot see around the curve. The present mode of economic relations, production methods, distribution mechanisms, political engagement, and energy production; our understanding of humanity’s position relative to “external nature”; the system of politically adversarial nation-states; those same nation-states’ positions in a rigid world-economic system; the presence of military conflict; social atomization – all of these elements of social existence and countless more will be altered by the metamorphic pressures of the coming total crisis. This inevitability creates two types of potential outcomes: the construction of an emancipatory, livable, fully-realized society; or the fall into a society increasingly composed along the barbaric trend-lines evident today. This epochal moment either breaks left, or it breaks right.

COVID-19 is not the harbinger of doom many subconsciously await with the sense of one waiting for the hammer blow to fall. It is, however, a signal and a model of the type of crisis we must anticipate and prepare for. The failure of the present could not be better illuminated than it is in the present disintegration. The present is intolerable and the future unthinkable. But to explore and demand the impossible is the task of revolutionaries, and our failure to take on this mantle will ensure our inability to seize the moment when future calamities emerge. To that end, we must formulate a program responsive to the needs of the masses of people, integrate ourselves into those groups most profoundly impacted by the implosion we are living through, and patch them together into a coalition capable of carrying our struggle forward into this brave new reality.

Responsive to this mandate, the formation of a new minimum program is the first and most urgent task of socialists today– particularly those in the West. We must begin to build a structured movement capable of responding, and even of assuming power the next time a civilizational collapse-level event emerges. And the first step in the way toward doing that is to build a program that addresses the critical needs of the masses of working people. The role of money, debt, stratospheric financial wizardry, foreign policy and international trade, and the structure of employment as a means of social control has never been more material than it is now. The purpose of those systems as a means of the restriction of access to resources has never been illustrated as clearly and starkly as it is right now. It is crystal clear which forms of labor are productive of value and which merely distribute, realize, and circulate value. It is also becoming clear how little of the value produced goes to the producers or to the general social good.

Critically, at a moment in which the US left is more nationalist than ever, this crisis is the first in an escalating series of crises that can only be remedied by internationalist socialism. The opportunity to promulgate a thoroughly internationalist politics and weave it into the existing left is the crux of this historical moment. Whether we do that will structure the outcome of the general collapse on its heels. Which fork in the path we choose may determine the survival of the species. The crossroads at which we stand must be understood as a unique opportunity to a) expand the class composition of the western socialist left; b) direct its politics in the necessary directions; c) incorporate swathes of working people toward a socialist politics of mutual self-interest; and, d) collectively take over the process of rebuilding (or not) the capital that will be destroyed by this many-sided crisis.

Moreover, this is a social rather than merely economic crisis, meaning it can only be effectively combatted through social solidarity, mutual aid, and democratically-run governmental initiatives. Economic crises often breed individualism, while more general, social crises breed mass politics and social cohesion. This is the first opportunity of this scale in many of our lives thus far, and we cannot let it pass.

In order to accomplish this essential task, the precondition for a socialist politics in the advanced capitalist core is being increasingly illuminated. This cornerstone is the precipitation of a mass, organized social movement with material social power which forms itself independent of and prior to participation in “official” politics. It cannot be wished into existence by way of electoral campaigns– especially not within the existing bourgeois unipolar political structure– or by trading in liberal-NGO cultural appeals. It must be built through the arduous, lumbering work of on-the-ground organizing. Fortunately for socialists, crises often catalyze the formation of such networks. We must attend to the material needs of our communities, build a package of demands responsive to those needs, and, in a coordinated campaign, target the crumbling mechanisms of maldistribution and social repression, and withhold our participation in them. There is no greater opportunity in recent memory to do so: people will be unable to comply with coercive maldistribution mechanisms such as rents and debt obligations, they will lack income but require the necessities of life, they will require medical care but be systematically denied access to it, and they will be exposed to hazards in the course of their work (should they have any) by indifferent or malicious capitalist corporations.

The contradictions are sharpening and they are incandescently clear for all who care to see. The socialist left often bandies this jargon about, often to the end of promulgating bad strategy and inadequate theory but in this case the process is actively accelerating and presents a crucial window of opportunity for real organizing toward social rupture.

Between Friend and Foe: The Democratic Party Primary and the Future of the Empire

Rosa Janis analyzes the Democratic Party Primary election as the symptoms of a dying empire that couldn’t die quite soon enough.

With the Democratic Party primary close on the horizon, we are set to witness one of the most important conflicts in American politics since 1968 being fought out on the battlefield of democracy. This battle will not only decide the fate of the Democratic Party but quite possibly the nation as a whole. While there have been other brutal conflicts waged within the confines of the Democratic Party, such as the all-out slugfest that was the 2008 primary election, this primary season might have world-historical value.

In his 1935 treatise, The Concept of the Political, the infamous political theorist and jurist Carl Schmitt put forward the thesis that the height of politics, the Political, as he put it, was defined by conflict. How political agents draw the distinction between friends and enemies (the “friend/enemy distinction”) determines not only the content of their politics but also their ability to win over the masses and wield the power of the sovereign. This thesis came out of the crisis of the Weimar Republic, now the Federal Republic of Germany. Carl Schmitt saw that the establishment comprised of liberals and normal conservatives was not able to engage with the political, and consequently unable to unite the German people against an enemy and thus protect their own state against the politically-minded Nazis and Communists. Carl Schmitt, being on the political right, decided to align himself with the Nazis despite his own personal reservations about Hitler, since the Nazis were, in his mind, the only ones who could possibly offer a political alternative to the Communists.

It seems that we are living in Weimar America, suffering through the military embarrassment that is the War on Terror, the lingering aftermath of the 2008 recession, and the looming crisis of climate change. The stability of the American Empire is questionable, to say the least. While we do not have Nazis and Communists fighting in the streets, there is a real conflict between political actors that is going on over the corpse of a rotting nation. As alluded to earlier, this conflict is the 2020 Democratic primary.

The battle within the Democratic Party seems, on the surface, to be simply a conflict between two relatively similar factions of the same political party: anti-Sanders establishment liberals and pro-Sanders social-democrats. But it is much deeper than that. The meaningful difference between establishment liberals and social-democrats is in how they both engage with the political; the contest for how they seek to draw different friend/enemy distinctions for the nation. The establishment liberals of the Democratic Party are drawing the friend/enemy distinction on the geopolitical level with their neo-Cold War rhetoric against Russia much in the same way that Nazis and neo-conservatives drew the friend/enemy distinction on the geopolitical level through pro-war rhetoric. On the other hand, the social democrats are drawing the friend/enemy distinction closer to that of the International class lines of old. The two different lines of struggle that these factions are pursuing will become more prevalent as both the American Empire and the world slide deeper into crisis.

The Crisis of Liberalism

The political establishment of the United States has been in a deep crisis since the end of the Cold War. With the death of the Soviet Union, every politician in Washington lost their most valuable enemy. The Soviet Union gave the United States a superpower to compete with on every level and provided a rationale for the commission of horrific acts of open imperialism upon the world in order to combat and contain the supposed evils of the Soviet Union. On the domestic level it created a coherent ideology of American liberalism to contrast the Soviet Union’s “totalitarianism” and allowed for social progress to be achieved through various reforms.

This crisis was not initially seen as a crisis but rather a victory. It was the end of History – liberal democracy was hegemonic across the world and the political establishment of Washington thought that they were going to be able to rule the world through technocratic non-political means. However, this sentiment was abandoned as conservative elements within the state, particularly that of the military-industrial complex, needed a compelling ideological narrative (i.e., a political one) to rationalize expanding its size and power. Thus the happy liberal consensus of the 1990s was traded out for the conservative war on terror of the 2000s.

Initially, the war on terror served its purpose well. The military-industrial complex was able to expand at a rapid pace, invading every aspect of American life through draconian measures such as the Patriot Act, and a new patriotic consensus was created in American politics around combating the threat of “radical Islam”. But as time went on, it became clear that “Islamism” could not fill the vacuum left by the USSR in American political consciousness. The threat of Islamic terror that was manufactured by the United States was vacuous compared to the Soviet Union, as there was no single nation-state that could truly compete with American hegemony. At first, it could be said that this was somewhat advantageous, as the United States was able to exaggerate the extent to which Islamic terrorism posed a threat to the Empire. It could make a geopolitical mountain out of the molehill of an extremely loose network of amateurish terror cells – which comprised Al Qaeda – by painting them as a vast secret network of deadly Islamic supersoldiers, armed with weapons of mass destruction and lurking among the innocent American populace. The incoherence and immateriality of “Islamic Terror” also gave the military-industrial complex free rein to attack whomever they wanted through manufacturing tangential evidence of terrorism.

This advantage, however, would quickly turn into a disadvantage beginning with the Second Gulf War. The American public was led to believe that Saddam Hussein had connections to Al Qaeda and was in possession of weapons of mass destruction, in order to justify an invasion of Iraq. But as the conflict transformed from a quick invasion to an apparently endless occupation, the public grew weary of the war. The evidence that had pushed the American public into the patriotic fervor for war in Iraq was slowly revealed to be non-existent and the fear factor of terrorism was lost on the American people. George W. Bush only won the 2004 presidential election by trading fearmongering about terrorism for fearmongering about homosexuals, thus dividing the anti-war John Kerry camp along culture war lines.

The second term of the Bush administration was dismal. The war in Iraq dragged on, unpopular as the president who was responsible for it. To top it all off, in the final year of the Bush administration one of the worst recessions in recent history hit the world economy, withering any hope for a Republican victory in 2008.

The Obama administration established itself on distinctly non-political terms, hoping to unite the nation after the 2008 recession. Obama ran a campaign that was full of vague slogans and cozy rhetoric of bipartisanship but devoid of policy initiatives. What would be catastrophic failures to any other administration, such as Obamacare being shot down almost immediately after the election (despite having a record-setting number of Democrats in both the house and the Senate), and managing a jobless recovery, did not seem to affect the public’s view of Barack Obama. This was probably due to the fact that the first black president was such a powerful symbolic accomplishment that not even a mediocre job performance could harshen the positive vibe that Obama enjoyed.

The Democrats did not understand that Obama was unique in this regard. In the moment just before the 2016 election, it seemed that the future was going to be apolitical Obama-era technocracy forever. The shifting demographics of America – old, white Republicans dying off to be replaced by a demographic rainbow coalition of Democratic minority voters – and the popularity of Obama were seen as evidence of this future. And despite the bitter memories of her vicious run in 2008 and the surprisingly hard time she had putting down a putatively socialist Sanders in the primary, no one doubted that Hillary Clinton would be the winner of the 2016 election. It was “Her Turn,” and this was only cemented in the minds of everyone in the media and liberal establishment by the out-of-nowhere victory of Donald Trump in the Republican primaries. Trump, being a buffoonish reality-TV show host with the 5th-grade vocabulary and no political experience, was seen as a pushover for Clinton. All the polls leading up to 2016 showed Hillary winning quite easily. With all this momentum behind her, Hillary did what no one at the time thought she could do: she lost.

The temporary fixes of War on Terror and Obama-era liberal technocracy could not meaningfully deal with the crisis of liberalism that came out of the demise of the Soviet Union. The Hillary campaign, with no real friend/enemy distinction to draw from in her ideology of politics-free liberalism, was left completely incapable of rallying their base to stop Trump. Trump, on the other hand, was easily able to harness the power of the political to his own ends. The rhetoric of “Building the Wall” was distinctly Sorelian and Schmittian in its character. It did not matter that a wall already partially existed in the form of border fencing which abutted bits of the Mexican-American border, that much of what Trump wanted to build was physically impossible given the uneven terrain of that border, and that even if Trump was able to get bits of his wall built it would not stop illegal immigrants from coming over since most of them come over via green cards. The wall was not a policy proposal but a myth. When the French theorist Georges Sorel pushed for socialists to advocate for the mass strike as a means of achieving the workers’ revolution he did not think of it as an effective strategy by itself. Rather, it was the confidence that would emerge from the idea of the mass strike – the myth of its power – that would compel workers to revolt against the ruling class and thus bring about socialism. Trump’s wall, much like Sorel’s general strike, was a myth. But that was its power. “Build the wall” became a rallying cry for responding to a combination of deindustrialization undermining the economic security of the poorest settler whites in key swing states like Pennsylvania and social progress getting under the skin of relatively well-off petit-bourgeois settlers. Through the myth of the wall, Trump was able to draw the friend/enemy distinction along distinctly racial lines in the 2016 election.

After the 2016 election, the Democratic Party was left in shambles. With their faith in the political ideology of Obama-era (neo-)liberalism crushed, the Democrats needed something else, and two options were laid out before them. Either they could follow the path set up by Bernie Sanders’ run in 2016, class struggle and old-fashioned social democracy, by moving toward the left of the political spectrum, or they could continue moving rightwards as they had done since the 1990s. The Sanders option was unviable for them, as modern American political parties are essentially fundraising mechanisms with political ideologies loosely attached to them. If the Democrats alienated their wealthy backers with the rhetoric of class struggle, the party would essentially fall apart. As a result, moving to the left was impossible for the Party, despite its half-hearted co-optation of the rhetoric of the Sanders campaign. The slogan of “Medicare for All”, for instance, became widely used among Democrats – despite their clear lack of intent to enact any such policy. The Democrats had to move rightward, but how to do this was not clear in the initial chaos of 2016. Then came the Steele dossier.

Russiagate Liberalism, Pete Buttigieg, and the Climate Leviathan

In the book Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future by Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann, the authors lay out a speculative future based on the liberal technocratic response to climate change. The label that they give to the possible future state is that of the climate Leviathan, the climate Leviathan being a kind of authoritarian world-state that grows out of the need to save capitalism from climate change. This is only one of the possible futures they lay out in their book. The others are: climate Behemoth (reactionary national regimes that respond to climate change through denial and closing borders); climate Mao (a resurgence of 20th-century Stalinism in response to climate change specifically coming from East Asian Maoists); and Climate X (a global revolution coming from the instability created by climate change).

Defined by a global state of exception, a combination of Malthusian and green-Keynesian economics imposed upon an unwilling international population, the climate Leviathan described by Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann appears to be wild speculative fiction, and to a certain extent that is a fair assessment. The authors overestimate the extent to which planetary sovereignty is or would be a desirable goal for technocratic liberal elites. While planetary sovereignty would certainly be a rational response, as climate change is a planetary problem and the United States in particular often acts as the “world police” with its foreign policy, there is no clear way for any of the Western powers to establish such a regime. The United Nations is a farcical institution with little power, so it’s highly unlikely that we’re going to get the Alex Jones-ian wet nightmare of the UN world-state. The authors point to the Paris Accord that was signed by Obama to suggest that liberals want some kind of planetary sovereignty, but this ignores the fact that the agreement was non-binding and therefore a mere symbolic gesture at most. The strongest evidence given by the authors to the idea that planetary sovereignty is something desired by liberals is bits of textual exegesis from Kant’s utopian essay “On Perpetual Peace” and a few powerless scientists calling for action. Even if it is hypothetically possible to create planetary sovereignty under global capitalism as it currently exists, the idea that the American military-industrial complex (which American liberals are a part of) would want to sacrifice even an ounce of its power to completing such a project seems absurd on its face.

What is more likely to be the technocratic liberal response to climate change is something that is in between the Leviathan and the Behemoth, a careful balancing act between a mild version of green Keynesianism and top-down economic fixes of the climate Leviathan to reduce carbon emissions side by side with the hardline authoritarian nationalism of the Behemoth to maintain the sovereignty of the American government in the chaos of our global crisis: a perfect compromise between wishy-washy “Center”-leaning Democrats and the more conservative-leaning military-industrial complex. The hows of achieving this bipartisan hell remained unknown until late in 2016 when the Steele dossier dropped into the hands of the liberal establishment. This bit of hit-piece journalism originally commissioned by the Hillary campaign in 2016 created a “new” narrative of Russian interference in American politics.