Translation and introduction by Matthew Strupp.

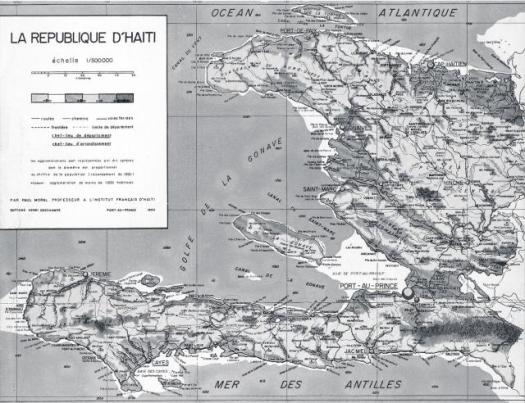

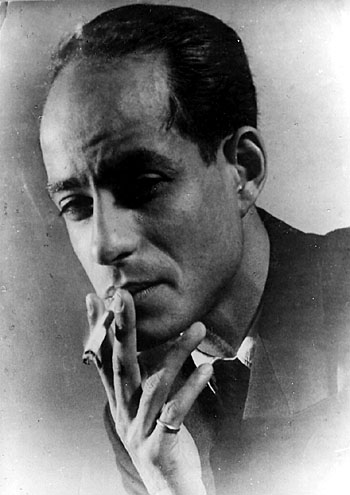

The following text is a translation of sections from Schematic Analysis 1932-1934, the founding document of the original Haitian Communist Party (1934-1936). The document was written by Jacques Roumain, a renowned Haitian writer whose 1944 novel, Masters of the Dew, was translated into English by Black U.S. communist poet Langston Hughes. The Schematic Analysis attempts to answer the burning questions of Haitian politics in the years immediately following the brutal US occupation of Haiti (1915-1934) from the standpoint of revolutionary Marxism. The main issues dealt with in the translated sections are the character of Haitian nationalism and the relationship between color prejudice and class struggle. The introduction reproduced here was not published with the pamphlet and was instead found among Roumain’s manuscripts. Regardless, it makes a bold and concise defense of the scientific character of Marxist theory and is therefore worthwhile reading. Excluded from the translation is the analysis of the Manifesto of the Democratic Reaction, a petty-bourgeois political trend of the time. This section dealt with issues of such specificity that it is unlikely to be of interest to a non-specialist present-day reader.

Roumain characterizes Haitian nationalism as “a shameless exploitation of the Anti-imperialism of the masses, to particular ends, by the bourgeois politician.” He says that its popular support was born out of a genuine mass movement that drove out the American occupiers and anti-imperialist sentiment with deep psychological roots, but that the bourgeois nationalists, because of their class position, were incapable of being truly loyal to this mass anti-imperialism and the economic demands of the proletariat and peasantry. The conclusion of this section is that the masses will more and more realize the necessity of a resolute struggle against both imperialism and its accomplice: the national bourgeoisie.

The thrust of the section on color prejudice and class struggle is similar. Roumain recognizes that color prejudice in Haiti has deep roots in slavery and the colonial period and that it was being accentuated in his time by the poverty of the Black proletariat, the proletarianization of the majority-Black petty-bourgeoisie, and the scorn of the majority-mulatto bourgeoisie for these subordinate classes. However, he warns that the question of color prejudice will be exploited by Black members of the bourgeoisie for political gain, while they remain loyal to the interests of their class as a whole. He demands instead a “proletarian front without distinction of color”, fighting under the Communist Party’s watchword “color is nothing, class is everything”, as the only thing that can “annihilate, at the same time as color prejudice, [the] social, economic, and political debasement” of the masses. Given the cynical use of popular resentment for the mulatto elite by the resolutely anti-communist Duvalier dictatorships later in Haiti’s history, this section is prophetic.

The original Haitian Communist Party ultimately failed to become a mass organization and did not survive its banning by the government in 1936. Despite the early demise of the party, this document is incredibly interesting as an object of communist study. It offers an approach to questions of theory, imperialism, nationalism, and prejudice within an imperially oppressed country in the aftermath of a crushing and exploitative occupation that is extremely lucid and resolute in its insistence on the importance of class struggle. Hopefully the historical example set by Roumain in this relatively understudied chapter of the history of our movement can serve to inspire future communist theoretical practice.

Introduction: The Necessity of Theory

Can the workers’ movement be progressive if it neglects theory? Even today we often meet practical workers who consider theoretical questions as side issues that are no doubt interesting, but devoid of real importance; sometimes, going farther still, they disdain theory as a waste of time.

It is certainly not impossible that someone who shares these views might pick up this little book and carelessly leaf through the first pages. If that is the case, it will be necessary to note that highly “theoretical” questions are dealt with here, and wishing to dissuade such a person from closing the book with impatience, we should attempt at the beginning a sort of justification of our aims. To be honest, we need to respond to the questions of this “practical” man: “What good is theory?” and “How can it help a practical worker carry out their work better?”

The best response will be to follow our friend “the practical worker” in their day to day struggle. In that which is their own field of activity, they soon discover, at each bend they run into that very theory that they so look down upon. They will find themself subject to the question “What is to be done now?” And the response always contains that other question: “What goal are you trying to attain?” In order to justify workplace action (a strike, for example) they are forced to appeal to general reasons (in this case: the general aim envisaged and the general experience of the strike tactic). But such general facts as these are linked precisely with that which we call theory, and if moreover, they show the characteristic of having been verified by experience, we call them scientific theory.

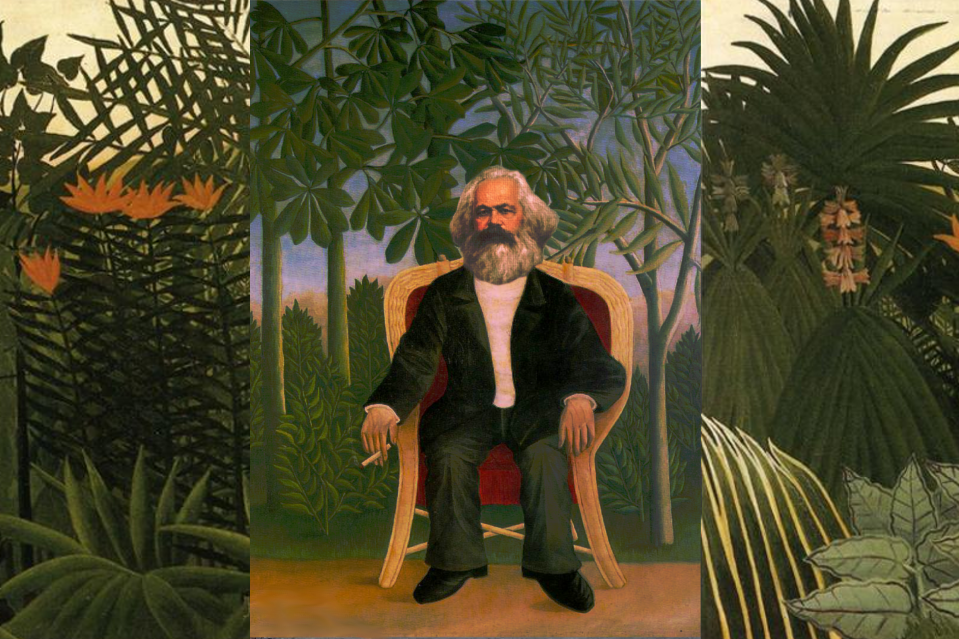

The theory which is at the base of all conscious socialist activity is scientific socialism (Marxism). This theory understands before anything else the strategy and the tactics of the class struggle in the strict sense. (The strike tactics mentioned above are one such detail). It requires equally an understanding of the historic economic roots of the class division of capitalist society, and of those laws of development of capitalist society whose weight was assessed for the first time by Marx in his great work: Capital.

The Proletarian Conception of the World

That which we seek, is a comprehensive worldview which will have its roots in scientific fact, and not only in those which are called the “natural sciences” (physics, chemistry, biology, etc.), but equally in the sciences of society and human thought.

Without such a comprehensive view, Scientific Socialism would not know how to complete itself, and would not be able to stand on its own legs. The elaboration of such a “conception of the world” or philosophy is of vital importance, because Scientific Socialism does not enjoy in contemporary society (bourgeois) universal approval. Well to the contrary, these essential theses are in conflict with the general concepts which dominate bourgeois society.

The bourgeois conception of the world is first of all conservative, and for this reason hostile to the scientific study of human society with all its revolutionary consequences. Second of all, it is commonly religious from the formal point of view, at the very least – looking at the existing order as if it had received some sort of divine sanction. Even when it is not overtly religious, it possesses these traits.

The Collapse of the Nationalist Myth

The most considerable fact, the one most rich in lessons is, between 1932 and 1934, the collapse of the Nationalist myth in Haiti. First of all: what is Haitian Nationalism?

Haitian Nationalism was certainly born of the American Occupation. But we misled ourselves in not seeing in it a sentimental attitude. Haitian Nationalism was born of the corvée reestablished in our countryside by the invading troops; of the massacre of over 3.000 protesting Haitian peasants; of the expropriation of peasants by the big American companies.

That is how Haitian Nationalism got its roots in the suffering of the masses, in their economic misery augmented by American imperialism and their struggles against forced labor and dispossession. Whatever the sentimental superstructure of these struggles, likely a historical relic, they remain no less profoundly and consciously an anti-imperialism based on economic demands: they are a mass movement.

The Haitian bourgeoisie, while the peasants of the North, the Artibonite and the Cental Plateau were massacred, received joyously the leaders of the killers in the salons of its society circles and in its families. Conscious accomplice of the Occupation, it put itself at its service, groveling at the feet of the masters for spoils: the presidency of the Republic, civil service positions! Some were content with this, others were not. In this way, a bourgeois opposition was born.

The parallel is striking between the class relations in Saint-Domingue and in today’s Republic of Haiti. French Colonists and American Imperialists. Freedmen and the contemporary bourgeoisie. Slaves and the Haitian proletariat.

A later work will explain the question in its smaller details. Today, we will keep ourselves to this: in 1789, the freedmen couldn’t think of the freedom of the slaves because they lived off their exploitation. They did not demand the extension of their rights. In 1915, the Haitian bourgeoisie, living off the exploitation of the masses, couldn’t make common cause with them: it contented itself, the historical and natural accomplice of imperialism, to call for the continuation of its privileges and for new benefits under the protection of the Occupier. The satisfied fraction collaborated “frankly and loyally”, the other revolted.

Once again, we reason here in terms of classes and not in terms of persons. There was, from one part and the other, traitors and sincere combatants. But considered generally, or better, in terms of classes: the bourgeoisie betrayed; the proletariat resisted.

On what was this underwhelming bourgeois opposition based? The masses, they had serious economic demands. To the bourgeoisie, economic demands are pillage. Naturally, they could not base themselves on them. Their nationalism was consequently only verbal. Their newspapers raised vehement complaints and drew on thousands of examples of well known patriotic clichés such as: “Our Ancestors, the noble va-nu-pieds of 1804 etc., etc.”

Some fines and imprisonments put all in good order. So it turned to the anti-imperialist masses, made it look as if it were defending their rights, as if it would take up their protestations against taxes and dispossessions, spoke with solemnity about the destiny of our race (that race that it looked down on and for which it had shame). The masses listened and followed. Haitian Nationalism was born, a fact unheard of: the bourgeoisie the vanguard of the proletariat!

So we define this nationalism: a shameless exploitation of the Anti-imperialism of the masses, to particular ends, by the bourgeois politician.

Between 1915 and 1930 the battle against the occupation and its Haitian underlings was engaged incessantly, in spite of massacres, bludgeonings, and incarcerations. It attained in 1930 its culminating point. President Borno “frank and loyal collaborator” stepped down from power. The masses, a mighty lever, hoisted the Nationalists into power.

With the arrival of the Nationalists into power, the process of decomposition of nationalism commenced. The explanation of this phenomenon is simple: at the base, the anti-imperialist, so anti-capitalist, movement. At the top, the opportunist movement of the petit-bourgeois and bourgeois management. Nationalism contained internal contradictions which broke it up. The nationalist movement was incapable of fulfilling its promises, because the promises of bourgeois nationalism collided, as soon as power was taken, with their class interests, and revealed themselves to be electoral trickery.

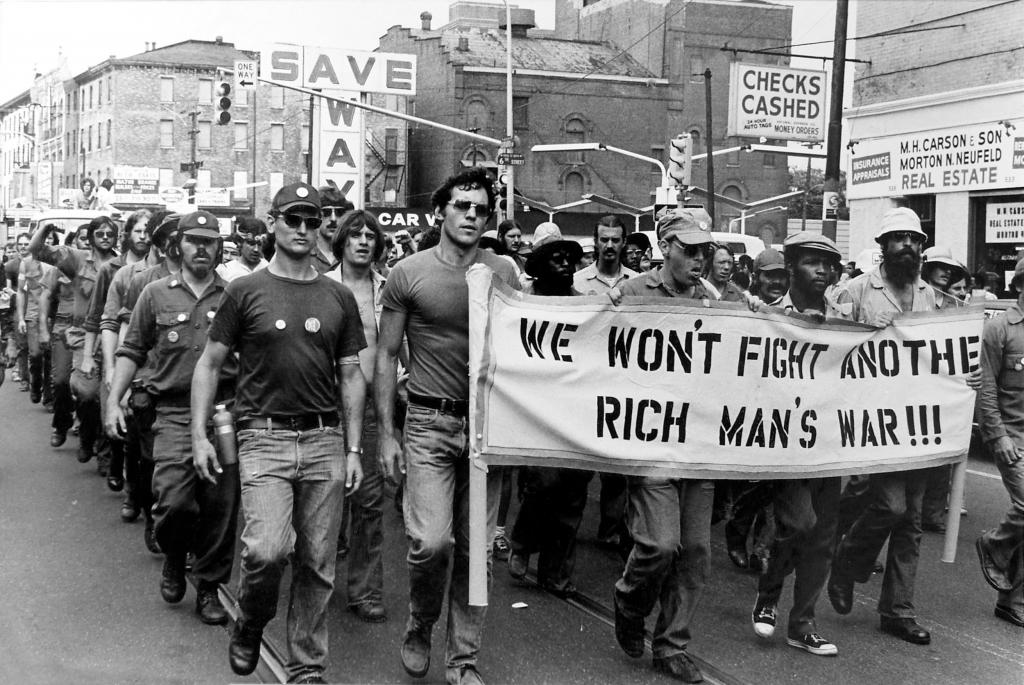

So the trade law was promptly buried for the reason that the interests of the minority exploiting class, consequently the Haitian state, are linked to those of international Capitalism. The project of the Jolibois-Cauvin legislation suffered the same fate. The small producers of alcohol continued to shut down their guildives; the agricultural workers were to work 10 to 12 hours a day for wages of 1 piastre, 50; merchants to be squeezed by market taxes; the workers to be exploited without recourse. As for returning the peasants dispossessed by the big American companies to the enjoyment of their land, it was totally out of the question. In this way, Haitian Nationalism collapsed. The great majority of the working class now understands the falsehood of bourgeois nationalism. More and more, it ties tightly the notion of the anti-imperialist struggle to that of the class struggle; more and more it takes into account that to combat Imperialism is to combat Capitalism, foreign or native, is to combat vigorously the Haitian bourgeoisie and the bourgeois politicians, servants of imperialism, cruel exploiters of the workers and peasants.

Color Prejudice and Class Struggle

Color prejudice is a reality that it is in vain to want to evade. And it is jesuitism that seems to consider it a moral problem. Color prejudice is the sentimental expression of the opposition of classes, of the class struggle: the psychological reaction to a historical and economic fact, the unimpeded exploitation of the Haitian masses by the bourgeoisie. It is symptomatic to note, at the moment when the poverty of the workers and peasants is at its height, when the proletarianization of the petty bourgeoisie proceeds at an accelerated pace, the awakening of this more than age-old question. The Haitian Communist Party considers the problem of color prejudice to be of exceptional importance, because it is the mask under which black politicians and mulatto politicians would like to evade the class struggle. These days, different manifestos where the problem is solved circulate clandestinely. One may gather from these manifestos that they expose 1.) sentimentally truths which are in reality economic and consequently social and political; 2.) the pauperization of the middle class, the reasons for which are explained in the critique of the Manifesto of the “Democratic Reaction.” But here it is a matter of specifying that the social, economic, and political debasement of blacks is by no means due to a simple opposition of color. The concrete fact is this one: a black proletariat, a majority-black petty bourgeoisie, is oppressed mercilessly by a tiny minority, the bourgeoisie (mulatto in its majority) and proletarianized by big international industry.

It is a matter, as we see it, of an economic oppression which translates itself socially and politically. So the objective foundation of the problem is therefore the class struggle. The P.C.H. poses the problem scientifically without by any means denying the validity of the psychological reactions of blacks wounded in their dignity by the imbecile disdain of the mulattoes, an attitude which is nothing but the social expression of bourgeois economic oppression.

But the duty of the P.C.H., a party which is incidentally 98% black because it is a workers’ party, and where the question is systematically cleared of its surface-level content and placed on the terrain of the class struggle, is to warn the proletariat, the poor petty bourgeoisie and the black intellectual workers against the black bourgeois politicians who wish to exploit to their profit their justified anger. They should be imbued with the reality of the class struggle, which color prejudice tends to evade. A black bourgeois is not worth more than a mulatto or white bourgeois. A black bourgeois politician is as ignoble as a mulatto or white bourgeois politician. The slogan of the Haitian Communist Party is:

AGAINST BLACK, MULATTO, AND WHITE BOURGEOIS-CAPITALIST SOLIDARITY: A PROLETARIAN FRONT WITHOUT DISTINCTION OF COLOR!

The petty bourgeoisie should come over to the side of the proletariat, because bourgeois and imperialist exploitation more and more rapidly proletarianizes it.

The Haitian Communist Party, applying its watchword: “Color is nothing, Class is everything”, calls the masses to the class struggle under its banner. Only against the national capitalist bourgeoisie (majority yellow, minority black) and the international capitalist bourgeoisie, is an implacable combat, combat cleared of its surface level content and situated on the terrain of the class struggle, susceptible, in destroying privileges owed to oppression and exploitation, to annihilate, at the same time as color prejudice, their social, economic, and political debasement.