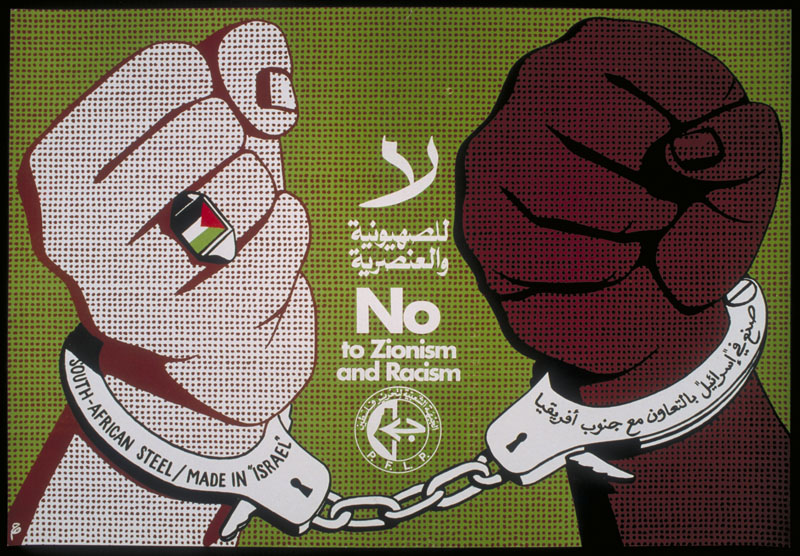

Lydia, Isaac and Rudy join Emmanuel Farjoun from Matzpen for a discussion on his 1983 piece Class divisions in Israeli society and how the divisions have changed in the present day. We discuss the changing strength of the Palestinians inside Israel and how that is reflected in their changing political aims, the differences between whiteness in the US and the construction of race in Israel, and the BDS movement internationally.

A Marxist Education with Wayne Au

Donald and Rudy sit down with Wayne Au, author of A Marxist Education. They discuss his experiences on providing a critical education, how education in the US currently stands and how Covid has just brought to the forefront issues faced by students. They discuss Au’s work on Paulo Freire and Lev Vygotsky, and end up envisioning how a socialist school could look like.

Republicanism and Freedom in Marx with William Clare Roberts

Ian and Donald join William Clare Roberts (@MarxInHell), author of Marx’s Inferno for a discussion on the wider themes of his book: republicanism, non-domination, theories of freedom, the early communist movement, and how to read capital both politically and scientifically.

Discovering the Cybernetic Brain

Amelia Davenport interviews philosopher of science and historian of cybernetics Andrew Pickering.

We live in a society without a future. Fewer people than ever believe in the lies pushed by corporate and government leaders of eternal growth and prosperity for all; it can’t be achieved on the basis of our current social structures. Even as we go to work and engage with our civil institutions, people increasingly simply do not believe in them. Apocalypse movies and books are incredibly popular. For instance, the television show The Walking Dead has reached 10 seasons and has two recent spin-off shows. We have impending climate disaster, stagnant wages, and the rise of what Marianne Williamson rightly calls “dark psychic forces,” in the form of movements like QAnon. For many, modernity has failed. We can keep on our current path, doubling down on its failures the way Margret Thatcher did with her neoliberal policies, out of blind faith that we just need to do more. We can put our faith in liberal democracy, technological innovation, bread and butter labor struggles, or struggles for representation within the system. Or, we can look to a different future; one where our current technology and philosophy merges with the best of the past, to produce a worthwhile synthesis.

To talk about this other future, and its implications for those of us who want a different world than the one we have, I (virtually) sat down with sociologist, historian, and philosopher Andrew Pickering. Andrew worked to excavate this other future in his book The Cybernetic Brain, while also contributing to the philosophy of science in The Mangle of Practice and Constructing Quarks. His historical and philosophical work covers the development and application of what he calls a “nonmodern” ontology. This framework is concerned with looking at how things in the world act in the world rather than the more prevalent focus on “enframing” things through fixed categories. This nonmodern ontology is the basis of cybernetics and a different kind of science (as proposed by Stephen Wolfram) than the one which dominates our academic, corporate, and military institutions.

Cybernetics, historically and contemporarily, has a place in all three of the above areas, but the original project was largely dismembered by the early 2000s. Although cybernetics’ origins in the military struggle against Nazi Germany and its role in the development of the Internet are relatively well known, less is known about its relationship to other important areas like ecology, eastern philosophy, and socialist construction. Pickering’s work is an invaluable contribution to a much broader discussion on organizational science and other ways of knowing beyond the paradigms we live under which have reached their limits.

Can you introduce yourself for our readers please?

I work in the history of science and technology, usually with a philosophical edge. My first book was Constructing Quarks, a history of particle physics; my latest is about cybernetics, The Cybernetic Brain. I feel like I’ve gone from one extreme to the other. Most of my career was in sociology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, but I came home to England in 2007 and now I’m an emeritus professor at Exeter University.

In The Cybernetic Brain, you describe cybernetics as having a sort of amateur character, but rather than a flaw, it seems to be a source of strength. Can you speak to that?

Disciplines shape the direction of travel. One reason for the grimness of American cybernetics was the urge to be ‘scientific’ (maths, logic, etc). I described the British cyberneticians as amateurs in the sense that there was no institutional apparatus holding them to account—so they could shoot off in all sorts of different directions, and sometimes it worked. More scope for imagination.

So you argue the imperatives the academy places on research limits the potential creativity in science? How might a young engineer or scientist interested in grappling with real social problems carve out a space to work on them?

There’s no magical answer, you just have to care. I could add that the amateurism of cybernetics was also a sociological problem. There were no jobs or obvious sources of funding for the second-generation cyberneticians. That’s one very mundane reason for the increasing marginalisation of cybernetics over the years.

What does it mean for cybernetics to be “counter-cultural”?

Modernity is basically dualist, implicitly or explicitly assuming that people and things are different in kind and need to be understood differently. Cybernetics is non-dualist, concerned with couplings between heterogeneous entities likeiike people and things. This is not just about ideas, but plays out in different practices. As documented in Cybernetic Brain, the affinities between cybernetics and the 60s counterculture were obvious: antipsychiatry, the Anti-University, explorations of consciousness, experimentation in personal and social relations, dynamic artworks.

Do you see any affinities between cybernetics and Non-European non-dualist philosophies? Certain strains of Hinduism, Buddhism and Nahua thought perhaps? Any direct influences?

Likewise what parallels and differences do you see between cybernetics and 19th/20th century holistic philosophies like Marxism or Kropotkin’s evolutionary anarchism? Do you buy claims that Marxist theorist Alexander Bogdanov influenced General Systems Theory with his Tektology?

The East: yes, sure, very many connections, though I only discovered many of them as I was finishing Cybernetic Brain. Eastern philosophy and spirituality is non-dualist leading to an obvious resonance with cybernetics (see above). Biographically, Stafford Beer was interested in India as a schoolboy and taught Tantric yoga in his later life. Grey Walter ’was a member of the Society for Psychical Research, very interested in altered states and strange performances. Ross Ashby declared himself a spiritualist and a time-worshipper. I think Gordon Pask was attracted to the doctrine of Universal Mind. Gregory Bateson worked with Alan Watts, one of the great popularisers of Buddhism in the west.The cybernetic worldview actually strikes me as Taoist.

I’ve always loved the Marx quote: ‘production creates a subject for the object as well as an object for the subject’—a beautiful expression of the non-dualist, non-modern coupling of people and things that cybernetics circled around. Beer had a lot of sympathy for Marx, but beyond that it’s hard to find much Marxist influence in cybernetics, or, indeed, any trace of Kropotkin or Bogdanov.

Why do you think cybernetics fractured into so many disciplines (control theory, bionics, Operational Research, etc)? Do you think it can create a second life outside official institutions?

In 1948, Norbert Wiener defined cybernetics as a kind of amalgam that included brain science, feedback engineering, information theory and digital computing. These were more or less held together in a series of interdisciplinary meetings (the Macy conferences, the Ratio Club, the Namur conferences), but later fell apart, reverting back to cybernetic vectors in individual disciplines. Cybernetics does still have a life outside the usual institutions. I run across traces of it in all sorts of places and, conversely, all sorts of people contact me about it.

I should emphasize that when I say ‘cybernetics’ I’m thinking about the branch of it that interests me especially, namely cybernetics as it developed in Britain in the work of Ross Ashby, Grey Walter, Stafford Beer, Gregory Bateson, and Gordon Pask.

Are there any particularly interesting projects or areas of research in cybernetics you know about?

Well, two areas interest me especially, both discussed further below. I’m just finishing a book on cybernetic approaches—though they don’t call themselves that—to the environment, approaches that seek to act with rather than on nature, to get along in the world rather than dominating it. The second area is cybernetic art, which I regard as a kind of ontological pedagogy, helping people to experienceexperfence the world as cybernetics understands it. (I got the idea of ontological pedagogy from Brian Eno, also mentioned below, though he’d never use that phrase.)

What kind of prospects do the organizational cybernetics of Stafford Beer have in future socialist experiments? Would you consider his project successful (insofar as it was cut short by the Pinochet Coup)?

A great thing about Stafford Beer was that his interest in democracy was not just a lofty aspiration but centered on forms of social organization. His Viable System Model and Syntegration are practical diagrams of how to organize collective decision-making in a minimally or non-hierarchical fashion. There are endless books and articles on why democracy is so great and why we need more of it, but very little, apart from Beer, on how to bring it down to earth. Project Cybersyn in Chile was a funny sort of success, inasmuch as (1) it encouraged Beer and others to think through further the politics of the Viable System Model; (2) it created a nucleus of organizational cyberneticians still active and influential today; and (3) of course, people are still interested in it, 50 years later. In practice, it hardly got started.

Can you explain the gist of the Viable System Model and Syntegration for our readers?

Beer thought that organizations needed to be ‘viable,’ meaning able to adapt to unforeseen changes. He therefore modelled his understanding of organization on the most adaptive system he could think of: the human brain and central nervous system. In the trademark version of the VSM, he divided the organization into five levels running from the board of directors to production units, and he insisted that couplings between levels should have a two-way give-and-take quality, not the top-down hierarchy of conventional organizations. He regarded the overall form of the VSM as the most democratic an organization could be while still remaining a single entity. Syntegration is a protocol for structuring non-hierarchic decision-making. Participants are assigned to the edges of a notional geometric figure (usually an icosahedron), with discussions alternating between the vertices at the ends of each edge. In this way arguments can echo around the figure in a decentred fashion. Beer thought of this as a sort of perfect democracy.

Against models of the mind that create a dichotomy between knowledge and lived reality, you say “knowledge is in the domain of practice”, what kind of implications does that have for you?

We’re brought up to think that knowledge comes first and somehow runs the show. I think knowledge is at most just a part of getting along in the world and is continually mangled in that process. One implication is that we can never know what will work til we’ve tried it.

What do you think of the value of AI like AlphaGo that is developed in a black box way? There is no real representation that we can extract. Its trained by trial and error with sample adversaries.

I think all knowledge is developed in a ‘black box way’ (see previous question). On the other hand, the basic function of neural nets is pattern recognition and I don’t think pattern recognition is a good model for human knowledge. We don’t walk around just pointing to things and saying ‘cat,’ ‘dog.’

Do you think developments in AI will have implications for socialists in terms of both what they’re up against and potential tools they can use?

Mainstream AI reinforces a very thin model of people as disembodied knowers, and modernity depends on this. Cybernetics began as brain science, but assumes a much denser and more interesting version of what people are like, which offers a basis for an important critique of and deviations from capital (see above on counter-culture).

So while AI attenuates people, when applied beyond narrow technical scopes, as it attempts to control behavior, cybernetics may prove to be a framework for escaping that kind of domination?

Oh yes! The subtitle of Cybernetic Brain is Sketches of Another Future. As I just said, the rational and logical brain is central to neoliberalism and the government of modernity, while the performative brain of cybernetics hangs together with all sorts of weird and wonderful nonmodern projects, as discussed in the book.

Do you see any potential for cybernetics in architecture and urban design in the future? Gordon Pask seems to have made a mark on the field.

Yes, of course. Pask was one of the leaders in thinking about adaptive architecture from the 1960s onwards, and is now a patron saint for some of the most interesting work in art and architecture.

What might a “Paskian” home or office building look like?

The key thing about cybernetic architecture would be that it is somehow reconfigurable in response to the actions of the people inhabiting and using it. I used to imagine waking up in the morning and trying to find out where the kitchen had gone. Pask’s prototypical contribution to architecture was the design of the Fun Palace, a big public building in London, conceived but not built in the early 1960s. The Fun Palace was a big shed with lots of moveable parts. Sometimes it would arrange itself to suit whatever people wanted to do (sports, education, politics, etc). Sometimes it would act to differently, to encourage people to find new things to do, new ways to be. The Pompidou Centre in Paris was modelled on the Fun Palace, but the dynamic elements were stripped away.

In what ways can cybernetics, ecology, and agriculture inform one another? Permaculture seems to have some shared principles with cybernetics despite generally being seen as “low tech”. Do you think there’s a possibility of a fusion between the approaches?

Gregory Bateson was one of the first to think cybernetically about ecology and the environment. His argument was that we need to think differently—non-dualistically—about the world we live in. I am more interested in practice—I think we need to act differently. From that angle, permaculture is quite cybernetic but not very exciting. I’ve been writing recently about a form of ‘natural farming’ developed in Japan by Masanobu Fukuoka, which, in effect, choreographs the agency of farmers, soil, plants, organisms in growing crops.

What are the key highlights of Fukuoka’s approach?

Wu wei—the Taoist concept of not-doing. What first struck me was the absence of plowing (and flooding in growing rice), but also not using chemicals as insecticides or fertilizers, not weeding, etc. Instead, the farmer times his or her actions to fit in with the shi of the situation, the propensity of things.

Can you explain what Hylozoism is? What kind of consequences do you think the concept has for changing our society’s relationship to the world?

Hylozoism (as I use the word, at least) is taking seriously the endless liveliness of the world. We live in a place we will never fully understand and that will always surprise us. We are not the center of creation; we are not in control; we are caught up in the flow of becoming. If we really grasped that we would be very different people and act very differently—modernity would be over.

Heinz von Foerster claimed that the basis of cybernetics is synthesis in contrast to modern Science’s basis in analysis. Would you agree with that characterization?

Kind of. A hallmark of conventional sciences like physics is ‘analysis’—breaking the world down into its smallest parts and understanding phenomena as built from the bottom-up. Cybernetics is not like that. Some cybernetic understandings instead emphasize ‘synthesis’—the idea that phenomena arise from systems or networks of interconnected parts. That’s how Gregory Bateson thought about the environment. On the other hand, the system aspect is much less salient in other cybernetic projects—Gordon Pask’s Fun Palace, for example.

I think it’s worth mentioning the time dimension of the contrast. Conventional sciences imagine the world to be built from fixed, unchanging entities (quarks, black holes, etc). Cybernetics—the branch of cybernetics that interests me—instead understands the world as a place of continual change in time, emergence, becoming.

Cybernetics is often seen as techno-fetishist but Norbert Wiener, Stafford Beer, and others were very critical of blind faith in technology. Why do you think there is this misperception and why do you think the founders of cybernetics were so skeptical of the power of technological development to solve social problems?

I’m not sure it is entirely a misperception. As I said at the start, many different threads are entangled in the history of cybernetics, including the sort of control engineering that is central to the automation of production, as well as the military devices Norbert Wiener worked on in World War II. That military connection is a sort of original sin for many people. Wiener himself refused to work for the military after WWII and warned of the dangers of automation, but I find it hard to think of any other examples. Beer had a rather uncritical vision of the ‘automatic factory’ in the early 1960s—a factory with no human workers at all. In Britain in those days the big danger of automation was seen to be the so-called ‘leisure problem.’ It’s hard to believe now, but the idea was that people would have nothing to do once their jobs had been automated so that the older generation would sit around all day watching the television while the young ones lived a life of delinquency (the plot of Clockwork Orange). The Fun Palace was conceived as an antidote to the leisure problem, a place where the population could recover the creativity that had been stifled by work, on the one hand, and the society of the spectacle on the other.

How do you think cybernetics impacted the Soviet Union and other East Bloc states? How was that different from its role in the Chilean model of socialism? Do you have any speculations as to why it failed to shape overall state policy despite having more institutional support than in the west?

There are many different threads and branches to the history of cybernetics. As I understand it, in the Soviet context ‘cybernetics’ meant the use of digital computers and computer simulations in economic planning. I’m not sure to what extent that succeeded; I think it was terribly overambitious, apart from anythiing else. One should consult the writings of scholars such as Slava Gerovitch, Francis Spufford and Benjamin Peters on this.

Perhaps the key difference between the Soviet and Chilean versions of cybernetics is that the former lacked the experimental aspect of the latter. Both featured computers and computer models, but while the Soviets aimed to optimise the performance of the economy, the aim of Cybersyn was to explore the economic environment and continually update plans and models in the light of what came back. Cybersyn-style experimentalism is the strand of cybernetics I have focussed on in my work.

If someone were to ask you what are the best resources for a non-specialist to learn about cybernetics and apply it to their own life, professional work, or political organizing, what would you tell them?

Yes, well . . . When I first became interested in cybernetics I tried to find popular or scholarly accounts that would help me get into it, and I failed. There wasn’t much that I could recommend then or now. My own solution was to go back to read the original writings of the cyberneticians, and that would still be a good tactic: try Grey Walter, The Living Brain (1953), Ross Ashby, Design for a Brain (1952) (what a title!), Gordon Pask, An Approach to Cybernetics (1961). Modesty forbids me recommending The Cybernetic Brain, but it’s a great story and not a bad read . . . Sketches of Another Future . . .

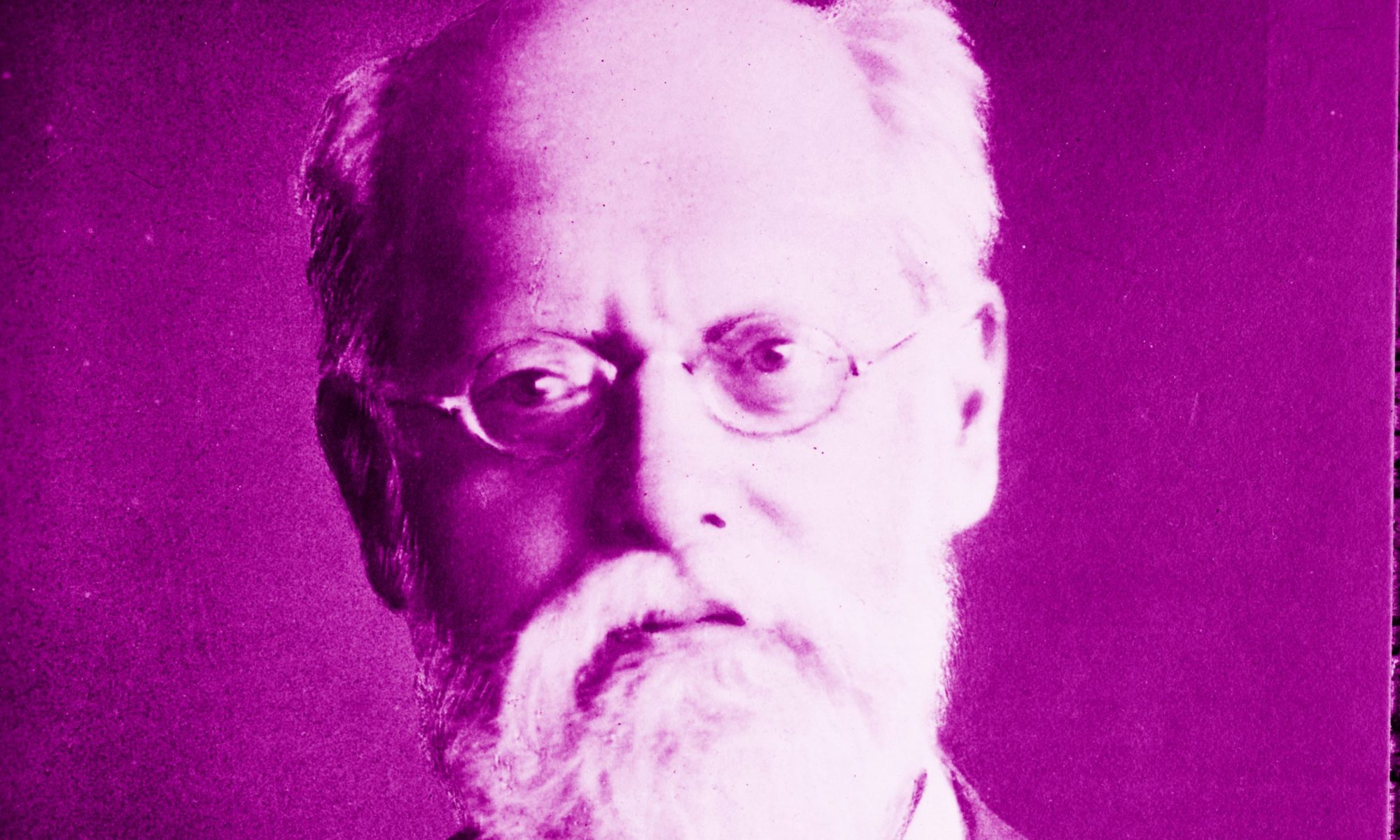

The Revolutionary Karl Kautsky with Ben Lewis

Parker and Alex have a conversation with the editor and translator of Karl Kautsky on Democracy and Republicanism (Haymarket, 2020) on the legacy of Karl Kautsky before he turned renegade. They discuss the convergence of various conflicting political views, from ‘Leninists’ to Social Democrats and Cold War Warriors, into what Ben Lewis calls in his book a “peculiar consensus” that fundamentally misrepresents the historical figure of Kautsky.

Please support Ben Lewis’s work Marxism Translated on Patreon as he strives to bring classical texts of German Marxism to an English audience for a first time.

The Chinese Rural Commune with Zhun Xu

Matt and Christian join Zhun Xu, author of From Commune to Capitalism: How China’s Peasants Lost Collective Farming and Gained Urban Poverty for a discussion on China’s communes from their construction to their dismantling. They contextualize land reform globally, elaborate on how the Chinese land reform process looked different from the Soviet one, discuss how the communes looked and functioned, and what services they provided as well as their achievements and their points of failure. They then take a general look at the cultural revolution, and how it was slowly reversed after Mao’s death, why and how the rural communes were targeted first for reform, and they finish by looking at the fate of the urbanized peasantry and why they have not yet joined the urban struggles in China.

Attic Communists of the Netherlands

Parker and Alex join Emil Jacobs of the Socialist Party of the Netherlands to discuss the factional struggle and expulsion of the Communist Platform group. They discuss the party’s bureaucratic centralism and opposition to open democratic struggle by the party’s parliamentary fraction. Should communists bother to try to push for principled politics within the broader workers movement? Why or why not? Emil also asks for context on the struggle for socialism in the US and the Democratic Socialists of America as well as Marxist Center groups.

Weekly Worker articles added for context and updates to the struggle within the Dutch SP:

https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1323/bureaucratic-control-freakery/

https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1325/youth-section-will-win/

The Tragedy of American Science with Cliff Conner

Alex and Rudy welcome historian Cliff Conner for a discussion of his recent book The Tragedy of American Science: From Truman to Trump. They discuss how this tragedy is a tragedy of capitalist science which is seen across the capitalist world, the role of science as an unchallengeable source of authority, and how that is squared with the anti-intellectualism needed to sustain a power structure, the influence of money in regulation and research, the precautionary principle and the risk-assessment principles for commercializing new products and the use of reductionism in research and how that is inseparable from the bourgeois mentality. The conversation then moves to the American university and the effect of the Bayh-Dole Act, and the relationship between military spending and research, including the US’s economic addiction to “weaponized Keynesianism” and how American policy makers do not care about the failures of military technology as long as the money keeps flowing. They discuss the ideals of objectivity and neutrality, ‘value-free’ science as an ideological tool, and how the social sciences can strive for objectivity. They end off talking about what changes and what things will stay the same with Biden, and how non-capitalist economies have shown that other models of science are possible where innovation did not rely on profit as a motive.

Buy Cliff’s book here. For early access to podcast episodes and other rewards, sign up for our Patreon.

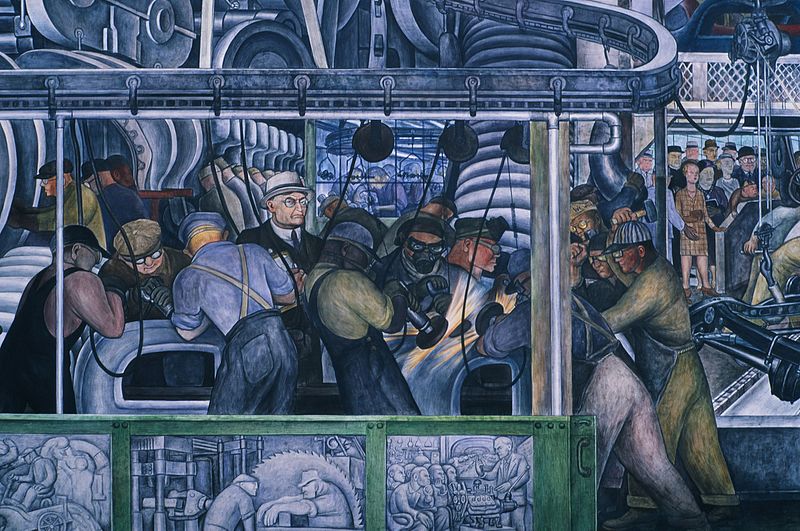

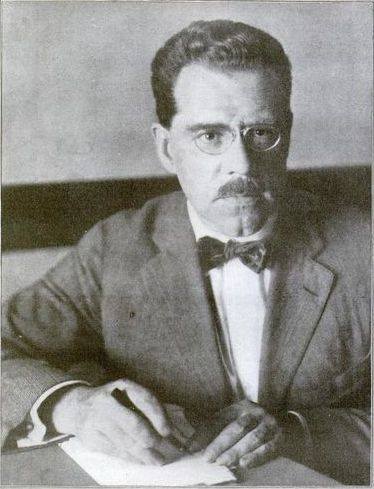

Walter Polakov and the Hidden History of Socialist Scientific Management

Walter Polakov had a combined passion for two seemingly contradictory ideas: scientific management and socialism. How did these two combine? Amelia Davenport interviews Diana Kelly, author of The Red Taylorist: The Life and Times of Walter Nicholas Polakov to bring light to this little known part of US history.

Walter Polakov (1879-1948) was a Russian-American Marxist, engineer, philosopher and scientific manager. Normally, the idea of a Marxist scientific manager would be appalling to both Marxists and the management studies community. Although scientific management was put into heavy use by the early Bolshevik government, it is usually written off as either a tragic necessity for industrialization or a prime example of the innate corruption of Leninism. For the part of management studies, the long-standing narrative that scientific management represented an inhumane anti-worker ideology which was supplanted by Elton Mayo’s benevolent “Human Relations” movement is near sacrosanct. But neither of these narratives can accommodate the much more complicated history of scientific management as a real current in history. While it is true that until shortly before his death Frederick Taylor himself opposed unions and always maintained a top-down approach to management practice, his views were by no means definitive of scientific management or even the Taylor Society founded in his honor. Many prominent members of the Taylor Society maintained socialist or otherwise anti-capitalist politics. After Taylor’s death the society even forged deep ties with organized labor. In fact, the Taylor Society openly endorsed strikes against employers who engaged in abusive practices. The Taylor Society played an important role within the International Labor Organization, UN agency tasked with promoting fair labor standards and the participation of organized labor in policymaking, and some of its alumni would even serve as staffers within militant labor unions in their struggles against the bosses. One such figure was Walter Polakov. Polakov spent much of his career as an advisor to the United Mine Workers in their most dynamic phase.

Within the pages of the Taylor Society’s bulletin, one can find spirited defenses of the Soviet Union, references to Rosa Luxemburg and August Bebel, and sharp denunciations of the capitalist system. By no means were all or even most Taylor Society members political or left-wing, but the culture of the movement was based around open debate and objective inquiry, not a sacred gospel. It’s this environment that allowed Polakov and his mentor Henry Gantt to advance notions that ran up against the prescriptions Taylor provided in Principles of Scientific Management. For instance, in Gantt’s Organizing for Work, worker participation in the development of new methods is highly encouraged and the notion of training workers to understand their work instead of simply acting as tools on behalf of management is strongly asserted. Although Gantt maintains a strict hierarchy of command within the rhythms of the active industrial production process, Polakov went much further in breaking with Taylorist orthodoxy. Polakov drew on his experience as an engineer and scientific manager of electric power production to rebuke Taylor’s inattention to the psychological and social needs of workers, his method of over-specialized administration, and his lack of inclusion of workers in the creative aspects of production. Polakov lays out his theories of organization in texts like Mastering Power Production, Man and His Affairs, and To Make Work Fascinating.

It is important to understand that Polakov’s socialist and pro-worker theories of organization were not in-spite of his scientific management, but rather an expression of it. Scientific management was a product of applying the principles of engineering to the production process as a whole. While engineering principles can be directed toward the maximization of output regardless of any other factors, it can also be directed toward the realization of other ends. For Polakov, this meant a borderline obsessive crusade against waste. Waste of time and waste of resources meant increased human toil and increased ecological destruction, which he saw as twin thefts from the workers. Taylor, on the other hand, saw idleness and inefficient labor methods as thefts from the general public of consumers and while employers saw them as a theft from their bottom line. Other Taylor Society members like African-American minister C. Bertrand Thompson argued for a more holistic accounting in texts like The Relation of Scientific Management to Labor. Where Human Relations smooths out contradictions between employers and workers, the Taylorists were consistently blunt and sober about them in their analyses, striving to give as-objective an account of the results of potential methods as possible. Knowledge of safe steel-milling methods and the rates of industrial accidents entailed by the use of particular coal mining techniques is as useful to organized labor as it is to employers.

The life of Walter Polakov, a man who dedicated his life to not only the cause of socialism but also practical improvements in the lives of workers, is criminally forgotten. In him, there was no contradiction between the broader goal of human emancipation and the day to day work of using science to make life better. Polakov spent much of his life tracked and harried by the FBI for his radical views and immigrant status, yet for his brilliance won himself a place at the table among the elite of American engineering. He would travel to the Soviet Union and apply his knowledge toward developing a more humane system of production than he found and return to the United States to fight for proletarians here.

Fortunately, the story of his life is no longer spread out among moldering archives thanks to the work of Diana Kelly. In The Red Taylorist, Kelly draws on a wealth of primary documents including FBI records to paint a compelling portrait of a man who persevered through hardship, persecution, and tragedy, while never wavering from his noble purpose. From his arrival in the United States as a bright-eyed engineer to his death as a penniless thrice-married divorce, the personal drama of Polakov’s life and the deep philosophical, political, and scientific problems are given excellent treatment. Below is an interview with Diana Kelly about her book, The Red Taylorist: The Life and Times of Walter Nicholas Polakov. I hope it will help shed light on Polakov’s significance to a new audience.

Can you give some background about yourself and your academic work?

First I was a schoolteacher – even in downtown New Zealand’s egalitarian welfare state, girls from poorish families couldn’t afford to go to University, but they could go into teaching (or nursing) and get paid for it. I went to Teacher’s College and began teaching middle school (primary). I came to Australia in 1968. For the next fifteen years, I was a wife and parent, teacher, and part-time University student studying history. Then I began tutoring at University and completed a Research Master’s degree in industrial relations in 1989. In 2000 I completed my Ph.D. dissertation – A History of Academic Industrial Relations in Australia. During the 1980s and 1990s, I researched, and coordinated, and lectured industrial relations (mainly undergraduate. Then I had a few years in leadership/ management roles, Head of School, Acting Dean, Director of International Studies, before shifting back into the History Department. I was also elected as Chair. Academic Senate a senior role I held for six years (the maximum term). Then in 2015, I returned to a full-time academic role, researching in a range of fields and teaching undergraduate history. In that time I have seen numerous changes sweeping through our university (and many others), changes which are destroying many of the important aspects of academia, such as academic freedom and academic governance, by and for, academics. My research has been rather eclectic – I have also written on the Australian steel industry, industrial relations, history of women, workplace bullying, and academic governance. I am currently writing on employers and workplace health and safety, especially with regard to industrial manslaughter. I would love to write more biographies because I believe biography can offer important insights not readily available in general histories.

What was your biggest challenge in researching the life of Walter Polakov? What attracted you?

I became interested in Polakov in the 1990s. An august colleague, Chris Nyland, had been researching scientific management for some years, and had obtained full access to Bulletin of the Taylor Society (now easily attainable given the internet, but not so much in the early 1990s). I was taken with the debates – the openness and collegiality (albeit, with undercurrents of personal tension!). What was a defining moment for me was to find Polakov propounding his ideas couched in primitive Marxist terms. I had seen signs of Progressivism in the debates but Polakov’s proclamations were something else, and, as a good ‘lefty’, I was hooked! All those years I had administrative / leadership roles, I could not do much research writing, but I could collect material, and my interest never waned.

The biggest challenges were first, that searching for, collection of material and secondly getting anyone interested in the paradox of the socialist scientific management. The great management historian, Daniel Wren, had written briefly of Polakov in 1980, and Nyland had mentioned him in some of his many works on scientific management, but there was very little available material. So those 15-20 years of searching and collecting in likely and unlikely places was a major challenge – especially from the far-distant Antipodes! Even when I had a basic story, many management history scholars were not interested because (a) it was about socialism and (b) it contradicted mainstream ideas that scientific management / Taylorism was unrelentingly bad for workers. Questioning the hegemon is never easy!

How would you define scientific management and to what extent do you consider it inherently anti-worker? Do you see any myths in management studies about this?

Scientific management is an ideology or set of principles about the use of people, equipment, and resources, at the workplace, industry, or nation. Central to that ideology are the importance of the application of research and the sciences to understand, first, WHAT is happening. That is very important – you cannot hope to manage scientifically if you do not understand what is being done. Second, HOW can the workplace, industry, or nation be improved? This requires measurement and investigation so that the scientific manager knows how to maximize equipment and resources and the working lives of workers. Thirdly, continuing measuring and monitoring to ensure that the best outcomes continue to be achieved. These principles stand in contrast to those who manage by whimsy, or “rule of thumb”, or simply on the basis of unquestioned managerial prerogative.

For many scholars in management, sociology, and labor history, scientific management is about deskilling, control, and exploitation of workers. I reject that strongly. There is no doubt that the notions of investigation, research, measurement and monitoring can be used for ill, but that was definitely contrary to the views of the Taylor Society and even Taylor himself. It is easy to pull out a few choice quotes from Taylor – but they are a-contextual and certainly not what Polakov and his fellow Taylor Society members thought.

Nevertheless less these remain the most immovable of myths outside of management history.

Which Taylor Society members do you think are most understudied?

Mary Van Kleeck (who made several trips to the Soviet Union and who was a union leader and a practical scholar, but was emphatic in her support of the Taylor Society.)

Henry Laurence Gantt (there is a thorough biography by Alford but it somewhat hagiographical, and skims over important aspects of Gantt’s life.)

Harlow Person (long-time director of the Taylor Society until it was taken over by the managerialists in the late 1930s)

Carl Barth (dour socialist mathematician whose advancements on slide rule technology were important for giving rigor to scientific management investigation)

King Hathaway and Robert Wolf were interesting and I have always been fascinated by Robert Valentine and the respect he was accorded in the Taylor Society, given his role in the Hoxie Report, but he died shortly after he presented his paper on Efficiency and Consent to the Taylor Society.

Why did some Taylor Society members turn against the market and the institution of private property? How did their views on worker autonomy and participation in management evolve?

The scientific managers gave what they saw as science, their greatest priority (research what is happening, what should happen, and how can we be sure it continues the best that can be done). That did not begin with an overt rejection of the market. Rather, it was simply that markets (and ‘financiers’) gave little value to science in management, to the best use of resources, equipment, and people. I am not sure that all scientific managers agreed with Polakov (except perhaps Van Kleeck and Barth?) on the generalised disgust with the market and private property, and Polakov himself always owned property.

Was there an orthodoxy in the Taylor Society, a plurality of views, or both?

Taylor Society debates (e.g. the one in the book over Drury’s paper, or another one mentioned over Valentine’s ‘Efficiency and Consent’ paper) suggest there was a plurality of ideas (political ideologies, social aspirations, values), but an unflinching commitment to science in management which of itself was an ideology.

To what extent can Polakov’s concern with energy and resource efficiency be of interest to ecological or environmental politics today?

I would have liked to have spent more time on Polakov’s commitment to energy and resource efficiency. Some of my readers have argued his greatest achievements were in raising issues of wastage of resource, and in these times with priority given to energy efficiency, Polakov’s insights and arguments offer valuable possibilities.

What effect did The Red Scares have on Polakov’s ability to work as an engineer or scientific manager? Is there anything you think Polakov’s treatment by the FBI can teach socialist technical specialists today?

My own belief is that one reason Polakov focussed on his engineering/management consultancy work was precisely that he could see what happened to activists, especially activist Russians, 1000s of whom were arrested. As well the so-called Red Ark that extradited many Russians, including Emma Goldman would also have influenced how he saw himself.

It would be hard to guess what the FBI is looking for today. The FBI under J Edgar Hoover was very focussed on socialists and communists because Hoover himself hated them. This is evident in the treatment of socialists compared with some pretty horrendous fascists, white supremacists, and the like.

Polakov returned from Russia after a relatively short tenure, how did his experiences there shape his views on socialism and political organization more broadly? How did he feel about Leninism and Bolshevik ideology?

We have no way of knowing how he felt – unless we had his papers which I am guessing were destroyed long ago. In the book, I tried to project my own interpretation that he felt conflicted about the Soviet Union under Stalin. He wanted communism to work – but he could see the flaws and had serious misgivings. In some respects, his perspective was useful because he was there at the request of Vesankha. It is likely he did not get the special tours of some contractors or visitor from USA.

I am not sure re Bolshevism and Leninism. Most of his ideals seemed to come straight from Marx – and from anti-revisionists with Luxemburg such as Bebel.

What can Polakov’s experience helping to organize Soviet industry tell us about life in the USSR and this attempt to create socialism in the workplace? What was the relationship between Polakov and Soviet Taylorists like Alexei Gastev?

Even under socialism, production needs management – and Polakov was the first to say so. On the other hand, I cite times when he found the Russian managers problematic and resistant to change. He circumvented the managers’ unhelpfulness by taking his questions/requirements to workers’ committees. Polakov, who had been a practicing scientific manager for over twenty years when he came to the Soviet Union, was clearly more flexible and perhaps also more democratic than Gastev. (This question deserves much further exploration!)

Can you please explain what a Gantt chart is and why it was so revolutionary? How did its introduction to Russia by Polakov impact the organization of production?

A Gantt chart is simply a visual plan of a project from conception to conclusion, and what is expected of equipment, resources, workers, and managers. In other words, the Gantt chart seeks to record ideal outcomes of all the variables of production, and then the actual outcomes as well. By monitoring all the variables, it becomes clear where problems may be equipment or power, for example, and helps workers and their managers monitor effectiveness. It was “revolutionary” because most production had previously been rule-of-thumb or ‘flying-by-the seat-of-your-pants’. As well it offered transparency – again something that the hierarchical Them v Us American businesses had avoided.

To be honest it would be hard to see almost any impact of Polakov’s work on production in the Soviet Union. I understand some Russian colleagues have explored this. I hope they can find archival material that would confirm or deny impact, but my guess is, sadly his sojourn in the USSR changed little. On the other hand there is evidence of the Gantt Chart being discussed in the early 1920s – and in this respect, I believe it would have been based on a Polakov translation. But no evidence yet, sadly.

Can you explain what Technocracy Inc was and its relation to The New Machine? Would you consider the Technocracy movement elitist?

In the book I hedge around the possible links between the New Machine (19i6-1919) and the Technical Alliance (1919-1921) and then Technocracy Inc (1933 – 1930s). Certainly Polakov seems to have been on the freinges of both TA and TI – he was cited several times as a lead author in their surveys. On the other hand he never fully commited to the TA or TI. I suspect Howard Scott had something to do with – he was one of those charismatic enthusiasts whose own knowledge may not have been as great as his enthusiasms – for Technocracy or the IWW, of which he was a member. I understand from some writings that Scott tended to alienate or overwhelm people. Polakov certainly held Technocratic ideas but I think he was tempered by his socialism and his deep commitment to the scientific management practices of research into what’s happening and what’s needed and what can be done … (as well as the democratic rule of engineers!)

What role did Polakov play in the United Mineworkers Union and how did he reconcile it with scientific management philosophy?

Polakov’s scientific management philosophy was as applicable to his work in the union as it was to his work as an engineering – management consultant. That is I hope a major point of the book – that scientific management ideology is not about control and exploitation of workers, but rather using science to make work and production, the best outcome possible. The reason that Polakov was raising safety and consultation and reasonable pay/ conditions from his earliest writings (and work as a manager), was that he saw these issues as centrally important as a means to achieve the best workplace environment for workers. People are way too conditioned to think of management as a hierarchical “my-way-or-the-highway” process so that they cannot see that scientific management ideology could be equally at home in a union as in a factory.

How did Polakov’s research into workplace safety help the union? What role did Polakov have in spearheading the development of Union Healthcare plans?

I believe Polakov’s role was significant in setting up the possibilities and furnishing the data for several really major health initiatives of UMW – I need to do more research still to make unequivocal claims.

How did Polakov use the language of management and accounting to force management to take workers’ concerns seriously?

All the scientific managers knew just how to influence managers and executive managers – just explain ideas in ways that are important to them. There is no point in telling a manager about how great a worker’s life will be with the scientific management initiatives because those managers are driven by priorities of output, return on investment, and next quarter’s profit. So the scientific manager needs to talk to the plant/organisation/industry manager in terms that he (and they were almost always he) would understand and which would motivate him. In the discussion of the Taylor Society debates in the book (p.41) even the not-very-leftist Colonel Coburn argued that with scientific management “… we are finding some facts and we are putting those facts into such shape that the financial man and even the director can understand them”. In fact, the financiers who owned the plants could no longer “grind the neck of the working man with an iron heel” as a substitute for proper management. (Coburn in Drury, 1917 p. 8) It was not that Coburn was a radical, but rather he could see how the ideology of scientific management could be framed to convince the financier or executive manager that fair working conditions were more effective.

Similarly, Polakov’s engineering monographs at UMW, and his paper to the employer-oriented National Safety Council sought to show employers how much the cost of accidents was a problem for employers. All his books emphasized the same things – he was writing to convince managers and the public who might influence managers that his scientific management initiatives of improved consultation, work, and safety conditions were about benefiting business – even as hr slipped in semi-plagiarised bits from Capital Vol 1!!

The FARC: Between Past and Future

Today we have an interview with Yanis Iqbal, a student and freelance writer from Aligarh, India, who has written many articles on the topic of the subaltern under neoliberalism and the topic of imperialism in Latin America and Colombia.

Q: Hello Yanis, first of all to get us started we have this question. Why are you interested in studying the FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] and Latin America?

A: I’m a student and freelance writer based in Aligarh, in India

I’m interested in studying FARC because of two reasons: Firstly, the contemporary situation in Colombia necessitates that we reanalyze the status of the FARC Guerillas in the country. Currently, violence against social leaders, environmental leaders and even Afro-Colombians has intensified. Colombian armed forces have killed indigenous peoples, journalists, part of the environmentalist Group for the Liberation of Mother Earth, and two other environmentalists have been killed. One of them was the president of the community action board of a village. And these killings belong to a systematic framework where social leaders, environmentalists, are being assassinated. 185 social leaders and human rights defenders have been assassinated in 2020 and more than 30 ex-FARC guerillas have been murdered in the same year. And under Ivan Duque, the killing of social leaders has intensified. Since Duque’s election to power in 2018, more than 500 social leaders and more than 80 ex-FARC guerillas have been killed. Within this general picture of violence we can analyze how FARC guerillas consist of more than narcoterrorism which is what the corporate MSM portrays them as in many countries. And their history is actually composed of forging hegemony. The analysis of FARC in the present-day concrete conditions is that FARC was more than a group of bandits.

The second reason is that the FARC organization has operated in the age of neoliberalism where the peripheries of global imperialism where the peripheries have suffered intensified exploitation. In neoliberalism, there has been a drastic decline of the left in the current stage and a complete dominance of capitalism. Existing in this new liberal era where analysis such as Francis Fukuyama has already declared the end of history. FARC has resolutely opposed the mechanisms of exploitation and pillage and has provided the left with a glimpse of what a materialistic optimism can look like. Whereas many leftists have chosen to satisfy themselves with measly electoral gains and have revered in meek reformism, FARC has continued with the supposedly Leninist thesis of smashing the state apparatus, thus proving to the world that a thorough revolution and a complete negation of capitalist conditions are still possible.

Q: How do you think the FARC compares to other groups like the Maoists in India & the Philippines? They seem to have similarities in the way they hold territory and operate?

A: Yes, their strategy is similar to other organizations. For this comparison, we can analyze the political philosophy of FARC. FARC does not have a foco theory, and they have followed the theory of PPW. While outlining this foco theory, Che had said that while conditions for revolution cannot be created by guerilla activity, the praxis of the guerilla group is both the cause of material conditions and the creation of material conditions. While he did believe that some structural conditions were necessary for guerilla activity, he wrongly deemphasized the work of preparatory social work giving a thrust to armed struggle. Che thought that a bond was created between the guerrilla and the people through the armed struggle itself, contradicting this claim FARC has maintained a model where power is accumulated by the establishment of broad support over long periods of time. It has undertaken careful and particular revolutionary work in the form of social welfare for instance, and this is a prerequisite for a socially embedded force. FARC’s organizational work has therefore involved the building of an alternative state within the state and establishing broad support. The local armed action has disrupted the state and has provided them with opportunities to emerge. And the state has not been able to deal with this disruption except with increased violence. FARC works by demoralizing the military with constant blows and delegitimizing the state by showing its inability to provide even a minimum welfare.

Q: One of the things that pop up is the big role of women in the FARC.

A: Women in the FARC have played an important role and the relationship of women in the FARC guerillas has been a bit ambiguous. 50% of members are female with 30-35% of the commanders also being female. The percentage of women in the Colombian government is 10%, with municipal levels being 5%. Only 2% of [Army] soldiers are female. In this sense, the FARC has involved a lot of women in its organizational activity and has involved them in their combat activity. This is a good sign, the high percentage can be explained by the fact that women see in FARC an organization that fights for their interest and can contribute to solving their problems.

While the work as a member of the FARC is dangerous, women’s membership in this group offers protection from daily violence. FARC even has created a zero-tolerance policy in regard [to sexual violence] with the punishment being up to death. This is an extreme policy but it has offered them protection and protects them against sexual violence both from their comrades and other groups.

Their membership also permits them actual freedom. While relationships must be approved by a commander both begin and end, permission is rarely withheld. To avoid a situation that could risk a woman’s allegiance to the cause, contraception is mandatory and pregnancy means the child must be either aborted or sent away. This can often lead to traumatic experiences and abortion was often one of the main causes of female desertion. Repeated abortion has repeatedly disillusioned female fighters and caused them to abandon the fact.

Q: What do you think of the change in FARC through the peace talks? How do you think this reflects on the philosophy of FARC?

A: The political effects of FARC’s demobilization have been huge on the subaltern classes in Colombia. The intense relationship between the internalization of the relations of oppression which inhibited the ability to antagonize the dominant classes and the potential to rebellion that indicates characteristics of autonomous initiative. With the demobilization of the FARC, I believe that the tense relationship has shifted to the internalization of the relationships of domination. When the FARC was engaged in armed struggle, it was totally opposed to the Colombian state and operated as an external actor opposed to this instrument of oppression. The relationship of antagonism was one of the few cases where an external actor attempted to undermine the external mechanisms of the Colombian state. This means that the political subject was completely and critically defined in relationship to the state, and the experience of subordination subjectively heightened by the FARC guerillas in relation to the state.

With demobilization, the guerillas have entered in a relationship with the state and have ceased being external actors. They are now struggling in and against the state as they are integrated into the state apparatus and participate legally in the political process. Consequently, this has meant a re-subalternization of the people who have experienced the de-intensification of the antagonism from rebellion to resistance. Resistance is the constitutive political action of subaltern subjects. The act of subjective emergence is the movement from passivity to action, from subjection to politicization. Nonetheless, it expresses a relationship of subordination as it cannot attempt to breach the regulation limits of the relationships of domination that establishes their concrete boundaries. The subaltern instantiates resistance and ultimately resistance is not merely a reaction but merely aims on a proactive level to modify its totality, negotiating the terms where the relationship of authority and obedience is exercised. Resistance does not reject the relationships of domination, since domination is permitted to continue. Resistance establishes a balance that allows for a permanent renegotiation where the subaltern classes forge a specific political subjectivity.

In contrast, [armed] rebellion questions the structures of domination by establishing life at the edges of this structure with the intention of ultimately subverting these structures. Rebellion tries to provoke a crisis of domination. With demobilization, FARC has entered a phase of resistance as the guerillas have been incorporated into the structures of dominance and are renegotiating their position within the system to actualize their situation.

Q: How did this group of 50 peasants grow up to be the FARC, such a large organization?

A: There are many factors that can explain the ballooning or strengthening of the FARC guerillas. They grew from a small force to a large organization through a strategy of socially embedded guerilla warfare wherein they listened to the practical necessities of the poor people and worked with them, helping the revolutionary culmination of class contradictions. Firstly, the guerillas were grounded in a highly unequal rural political economy in which the majority of the rural people are agricultural laborers or precarious owners of extremely small crop farms facing constant displacement by rich actants. Displacement in Colombia is a large-scale phenomena and it is estimated that displaced farmers were forced to abandon more than 10 million hectares of land.

In addition to small-scale subsistence farmers, coca farmers present another section of oppressed people who are strengthening the FARC organization. Sometimes small scale farmers are forced to cultivate coca by a nexus of drug traffickers and paramilitaries. When paramilitaries arrive at a certain region they make it clear that those who wish to remain living must cultivate. FARC, by combatting paramilitary violence and instituting social welfare projects was able to gain a foothold in rural regions of Colombia.

Take an example, in Putumayo for example FARC’s daily activities have made them social actors which could intervene in the civic strikes, help the peasants and magnify the impact of the marches by organizing the campesinos to stay mobilized months at a time. By lending support to the movement, FARC helped strengthen the movements’ negotiating capacity to manipulate the state. On top of providing logistical support, FARC guerillas have also been combatting political violence and essentially stabilizing the life of the movement. Instead of drug use, the FARC have regulated the coca trade for the benefit of growth. They control the majority of the coca growing territory and that’s for a reason. If they didn’t have that control, the paramilitaries would come into the coca growing territories laying waste to the peasants. They are a bigger threat. Paramilitaries do not care if they have to kill to steal the product. FARC therefore utilizes a passive mobile warfare strategy and Marxist-Leninist ideological unity, to resist the onslaught of paramilitaries and narcos, and guarantee a minimum level of income to coca growers.

This combative capacity to resist para institutional violence was developed at the 7th conference of the guerilla movement, where FARC declared itself as a people’s army. And this also helped it consolidate itself and grow into a large organization since this now meant that the party would no longer wait and ambush the enemy but surround it. This was the transition of the guerillas from a defensive organization to a revolutionary offensive movement geared towards more offensive military operations and protecting the oppressed people.

Talking about social welfare projects. 50% of the taxes from coca-based production has been invested in infrastructure projects. This is done regularly. Besides regulating the coca trade, they incentivize the growers to plant food crops to attain a certain level of food security. Through these small strategies, FARC has attained hegemony and has consolidated itself.

Q: How important do you think is the FARC’s ideological unity as compared to the role of its standing army and the broad coalition of movements it represents?

A: FARC’s ideological unity and military strength can’t be analytically separated out into two separate components. Both these elements have cohesively combined to produce a “politico-military” unity. While military capacity ensured that the FARC was able to materially provide existential support to various oppressed social sectors, ideological unity sowed the seeds of revolution in that existential support and helped in the political symbolization of FARC’s military offensive. Here, we can observe a dialectical unity between FARC’s ideology and its combative strength. If the guerrillas had only given security to the masses without any revolutionary education, a stasis would have been produced where the people passively relied on some armed actors for protection from paramilitaries and multinational companies. But instead of doing that, FARC lubricated existential security with ideology and thus, politically mobilized the people. Now, we can say that FARC’s organizational-operational activities consisted of the material construction of counter-hegemonic de facto governments and the carrying out of activities such as obstruction of roads, attacks against infrastructure, extortion and kidnapping, sabotage, ambushes, control of mobility corridors, and generation of resources. Through these activities, the guerrillas subjectively translated the discontent with the objectively oppressive conditions into a dialectically grounded revolutionary optimism. This revolutionary optimism stemmed from the institution of ideologically-informed small material-economic changes that brought superstructural changes in the consciousness of the masses, convincing them of the materially grounded possibility of radically re-configuring the existing social relations of production. Looking at your question from this conceptual prism, one can say that FARC’s ideological unity and military capacity exist in a dialectical balance to mobilize the various social sectors.

Q: Which factors do you think have contributed to FARC’s failure to break down the military in Colombia and disarm the Colombian state’s armed forces?

A: FARC has not been able to weaken the military because of the military campaigns waged by the state and the imperialists. Through Plan Colombia, implemented in 2000, the privatization of violence and the installation of asymmetrical warfare took place. Through this, security companies operated on Colombian soil using specialized violence to defeat the guerillas. The military magnitude of these private companies is indicated by the fact that in 2005, for example, there were 2000 private military contractors on Colombian soil.

Second, the system of asymmetric warfare with new military modalities has also hurt FARC. This was designed by the USA, who integrated the operations and provided advice to implement the process. These changes have allowed for the military to be at a tactical advantage. Through this army modernization, the Colombian state was able to kill three important leaders of FARC and this did a lot of damage. Martin Dempsey, a US army general, had said in 2012 that the US would send to Colombia brigade commanders with experience in Afghanistan and Iraq to train and work with the Colombian Police and Army combat units, to be deployed in areas controlled by the rebels. These brigade commanders were already existing commando units for counter-intel missions. These aggressive military campaigns reduced the FARC guerillas by 50%. And paramilitaries have quickened the military defeat of the FARC by establishing the everyday-ness of violence. Through a network of microaggressions they have created an omnipotent atmosphere of perpetual violence. Despite the demobilization of paramilitaries in 2006, various organizations continued to exist, destabilizing and weakening the military structure of FARC.

Q: But Plan Colombia has only been there for the last 20 years. As a principle the armies in Latin America have tended to be reactionary. There have not been many leftists groups which have won the support of the army. It’s not just about Colombia or Plan Colombia, right?

A: Right, armies cannot take the side of the people because they are part of the instruments of violence of the state.

Q: But in other places, armies have been disrupted by revolutionary movements.

A: I think it is hard to explain this, but I can give an example. In Bolivia the army supported a coup even if they earlier supported the government of Evo [Morales]. Now they lend their support to US puppets, and this seems to be a historical tradition in Latin America, but I don’t really know the factors which can explain it.

Q: It seems to me that ever since the demobilization of FARC, the Colombian left has found much more support in urban areas again; as in the election of 2018, that saw Gustavo Petro come second in the presidential election, a leftist ex-guerilla from Humane Colombia. How do you think the future of the left in Colombia looks?

A: To explain the future of the left in Colombia we have to first look at the concrete conditions which have been implemented by the peace agreement, which are going to consolidate leftist politics in Colombia. The peace agreement can be seen as a passive revolution, functioning as a ruling class counter-movement that has marked important but limited changes, and has acted as an antidote to FARC’s revolution from below and the significant pressure from the subaltern classes. So after the peace agreement, neoliberalism has intensified in the form of the productivity increase in the extractive sector such as coal, emeralds, and other resources. And foreign direct investment has also increased by 25%, another important factor. This indicates that neoliberalism is consolidating in this post peace period. And these conditions are going to be conducive factors for the left. As the objective conditions exacerbate, the political potentialities for the left are going to consolidate. And as the ongoing realization of which peace has been achieved dawns on the Colombian masses, class struggle is set to intensify and the political prospects of the left will likely improve.

During the peace process, the leftist political fraction had supported the need for replacing neoliberalism and installing an integrated rural program. As the crisis exacerbates, more people will identify with the revolutionary demands of leftist politicians. These politicians can exploit the deep disaffection of the coca growers with state-sponsored military offensives and intimidation in the coca producing regions. Whereas leftists try to cater for a regulated program with lesser crop distribution and comprehensive rural development, the current government’s overtly militaristic tactics are not a solution. Comprehending this contrast between those two approaches, coca growers are bound to lend support for the leftists as the state’s repressive tactics to achieve coca eradication are tied to large military operations.

Despite the good political possibilities for the left, there still are two major problems. Colombia’s history of violence where the carefully constructed hegemony of electoral leftists has been sapped by the violence enacted by the ruling class. For instance, in the 1980s the FARC had agreed a ceasefire with the Betanzos regime. And many of its militaries had opted for electoral politics by forming a mass electoral party called the Patriotic Union. The Patriotic Union had substantial electoral support with 21 elected representatives in parliament. But before, during, and after scoring these substantial wins in local and state and national elections, the military squads murdered three of these elected candidates. Over 500 legal electoral activists were killed and the FARC was forced to return to arms because of the Colombian regimes’ mass terrorism. Between 1985 and 2000 many peasant leaders, human rights activists, and other figures have been assassinated. This historical precedent suggests that in the current conjuncture, where oppressive objective conditions are amplifying, the peace process has been torn apart. Leftist political candidates are being murdered by state-sanctioned violence, and the recurrence of targeted violence in 2019-20 are possible political breaks to electoral politics.

Q: Just this week there was another massacre where many people were killed. This is a recurring theme. Staying on the topic of the 2016 peace agreement… The demobilized FARC soldiers are complaining in interviews that farmers in Colombia still have no land, even if the 2016 peace agreement promised it. There is still no land reform and farmers still suffer under the minority, 1% of landowners who own most land. What do you think of FARC’s agreement in general? Is the faith in the electoral process or a civic solution naive or justified as a solution to paramilitary terror?

A: Colombia is entangled in the web of capitalism. Because of its very specific conditions and the entire arrangement of imperialism, paramilitarism has been economically admitted into this integrated system of capital accumulation and functions as a structural condition and not a temporary condition. Paramilitary activities are below the political realm of rising ideology or the military realm constituted by the national armed forces and the appropriation of land. Paramilitaries function in the structure by securing a suitable investment climate by not only combatting the guerillas but by displacing rural residents and providing security for companies that take over these lands, and attacking labor unions that fight against neoliberal policies and fight privatization. In a nutshell, paramilitaries serve to clear the ground of anything subversive that would fight the advance of capital or oppose neoliberal policies. Those who believe in a civic solution to the paramilitary terror have to ask themselves the following question: is the judiciary or any state apparatus going to intervene to stop paramilitarism and curtail the process of capital accumulation that is highly important to Colombia’s ruling classes with Colombia’s vast resources?

Moreover, there is already a history of people like Uribe having strong differences between what is said and what is done regarding paramilitarism in the ground reality. For example, paramilitarism was outlawed in 1989, but in the 1990s there was a boom in paramilitary activities. Taking cognizance from these facts, and stating that there have been paramilitary pressure from below on social movements, a civic solution to violence would find it hard to survive on the basis of that pressure.

Q: Do you think the recent proliferation of Unions has to do with FARC using its money to prop them up?

A: The proliferation of trade unions is unrelated to the FARC because FARC does not have the requisite financial resources to fund different groups. Under the peace accord, the FARC’s funds had to be declared and surrendered to the government to be used to compensate the millions of victims of the 60-year conflict. In the peace agreement, there were subsections called the “Strategy for the effective implementation of the administrative expropriation of illicitly acquired assets” and the section 3.1.1.3 “Provision of information” of the “Agreement on the Bilateral and Definitive Ceasefire and Cessation of Hostilities and Laying down of Arms” which required the FARC to give up its financial resources. All this happened while the FARC-EP remained in the Transitional Local Zones for Normalisation (TLZNs) in the process of laying down arms. So, now the FARC does not have sufficient monetary clout to financially influence trade unions.

Q: To sum up… how does this link to your other interest of the neoliberal ethos? I guess if you don’t take up arms again the only thing really left for you is to become a neoliberal subject.

A: In the current period, we have neoliberalism as a social structure of accumulation, and have started a process of subjectification in which new subjectivities have been created. I would highlight four changes, or elements to this structure: they are radical abstraction, entrepreneurship of self, growth imperatives and effect management. Firstly, radical abstraction is the extraction of individuals from their economic conditions, this results in the elimination of local languages and struggles, and the imposition of dominant cultures which facilitate the growth of consumptive environments. So along with the loss of regional struggles and anti-accumulation struggles, radical abstraction also causes precarious existence abstracted from material conditions. You are told that you can do anything, and you can build anything, and this increases the impact of structural conditions on you.

Second is the entrepreneurship of self, which is the individualization of the subject. In this, the individual sees themselves as a portfolio of investment. Third is the growth imperative, which encapsulates the urge to seek new investments and diversify risks. And the growth imperative is an integral element in neoliberalism because it itself is the perpetuation of capital accumulation and the constant search to devise new ways to maximize profits. The last is effect management, which is a method that neoliberalism uses to manage culture. In this effect management, positive effects are over-highlighted to obscure what Gramsci calls “the pessimism of the intellect”, and prevent people from understanding structural conditions exercising a downwards impact on them. And qualitative effects also decorate the self by energizing them to go about taking risks of aspirational desires.

Q: If you encourage people to take more risks wouldn’t that backfire and cause them to join a guerilla?

A: That’s a possible cause of action, but there’s also the structure. They take the risks from a predetermined repertoire, and guerilla activities are out of this repertoire.