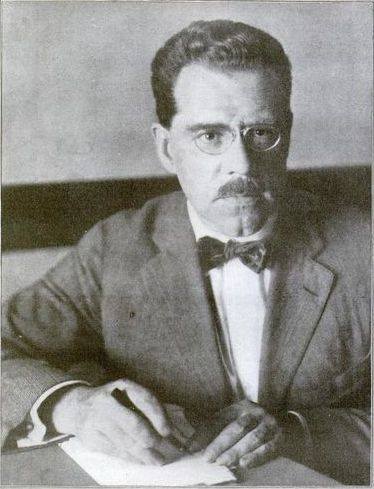

Walter Polakov had a combined passion for two seemingly contradictory ideas: scientific management and socialism. How did these two combine? Amelia Davenport interviews Diana Kelly, author of The Red Taylorist: The Life and Times of Walter Nicholas Polakov to bring light to this little known part of US history.

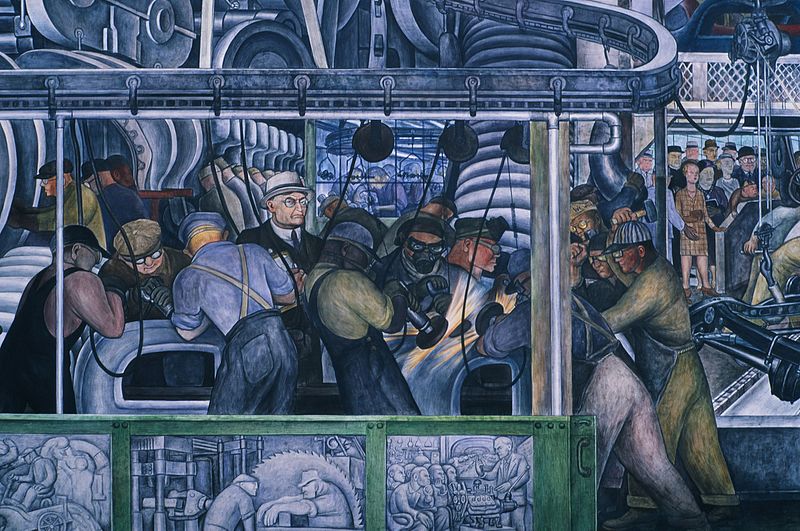

Walter Polakov (1879-1948) was a Russian-American Marxist, engineer, philosopher and scientific manager. Normally, the idea of a Marxist scientific manager would be appalling to both Marxists and the management studies community. Although scientific management was put into heavy use by the early Bolshevik government, it is usually written off as either a tragic necessity for industrialization or a prime example of the innate corruption of Leninism. For the part of management studies, the long-standing narrative that scientific management represented an inhumane anti-worker ideology which was supplanted by Elton Mayo’s benevolent “Human Relations” movement is near sacrosanct. But neither of these narratives can accommodate the much more complicated history of scientific management as a real current in history. While it is true that until shortly before his death Frederick Taylor himself opposed unions and always maintained a top-down approach to management practice, his views were by no means definitive of scientific management or even the Taylor Society founded in his honor. Many prominent members of the Taylor Society maintained socialist or otherwise anti-capitalist politics. After Taylor’s death the society even forged deep ties with organized labor. In fact, the Taylor Society openly endorsed strikes against employers who engaged in abusive practices. The Taylor Society played an important role within the International Labor Organization, UN agency tasked with promoting fair labor standards and the participation of organized labor in policymaking, and some of its alumni would even serve as staffers within militant labor unions in their struggles against the bosses. One such figure was Walter Polakov. Polakov spent much of his career as an advisor to the United Mine Workers in their most dynamic phase.

Within the pages of the Taylor Society’s bulletin, one can find spirited defenses of the Soviet Union, references to Rosa Luxemburg and August Bebel, and sharp denunciations of the capitalist system. By no means were all or even most Taylor Society members political or left-wing, but the culture of the movement was based around open debate and objective inquiry, not a sacred gospel. It’s this environment that allowed Polakov and his mentor Henry Gantt to advance notions that ran up against the prescriptions Taylor provided in Principles of Scientific Management. For instance, in Gantt’s Organizing for Work, worker participation in the development of new methods is highly encouraged and the notion of training workers to understand their work instead of simply acting as tools on behalf of management is strongly asserted. Although Gantt maintains a strict hierarchy of command within the rhythms of the active industrial production process, Polakov went much further in breaking with Taylorist orthodoxy. Polakov drew on his experience as an engineer and scientific manager of electric power production to rebuke Taylor’s inattention to the psychological and social needs of workers, his method of over-specialized administration, and his lack of inclusion of workers in the creative aspects of production. Polakov lays out his theories of organization in texts like Mastering Power Production, Man and His Affairs, and To Make Work Fascinating.

It is important to understand that Polakov’s socialist and pro-worker theories of organization were not in-spite of his scientific management, but rather an expression of it. Scientific management was a product of applying the principles of engineering to the production process as a whole. While engineering principles can be directed toward the maximization of output regardless of any other factors, it can also be directed toward the realization of other ends. For Polakov, this meant a borderline obsessive crusade against waste. Waste of time and waste of resources meant increased human toil and increased ecological destruction, which he saw as twin thefts from the workers. Taylor, on the other hand, saw idleness and inefficient labor methods as thefts from the general public of consumers and while employers saw them as a theft from their bottom line. Other Taylor Society members like African-American minister C. Bertrand Thompson argued for a more holistic accounting in texts like The Relation of Scientific Management to Labor. Where Human Relations smooths out contradictions between employers and workers, the Taylorists were consistently blunt and sober about them in their analyses, striving to give as-objective an account of the results of potential methods as possible. Knowledge of safe steel-milling methods and the rates of industrial accidents entailed by the use of particular coal mining techniques is as useful to organized labor as it is to employers.

The life of Walter Polakov, a man who dedicated his life to not only the cause of socialism but also practical improvements in the lives of workers, is criminally forgotten. In him, there was no contradiction between the broader goal of human emancipation and the day to day work of using science to make life better. Polakov spent much of his life tracked and harried by the FBI for his radical views and immigrant status, yet for his brilliance won himself a place at the table among the elite of American engineering. He would travel to the Soviet Union and apply his knowledge toward developing a more humane system of production than he found and return to the United States to fight for proletarians here.

Fortunately, the story of his life is no longer spread out among moldering archives thanks to the work of Diana Kelly. In The Red Taylorist, Kelly draws on a wealth of primary documents including FBI records to paint a compelling portrait of a man who persevered through hardship, persecution, and tragedy, while never wavering from his noble purpose. From his arrival in the United States as a bright-eyed engineer to his death as a penniless thrice-married divorce, the personal drama of Polakov’s life and the deep philosophical, political, and scientific problems are given excellent treatment. Below is an interview with Diana Kelly about her book, The Red Taylorist: The Life and Times of Walter Nicholas Polakov. I hope it will help shed light on Polakov’s significance to a new audience.

Can you give some background about yourself and your academic work?

First I was a schoolteacher – even in downtown New Zealand’s egalitarian welfare state, girls from poorish families couldn’t afford to go to University, but they could go into teaching (or nursing) and get paid for it. I went to Teacher’s College and began teaching middle school (primary). I came to Australia in 1968. For the next fifteen years, I was a wife and parent, teacher, and part-time University student studying history. Then I began tutoring at University and completed a Research Master’s degree in industrial relations in 1989. In 2000 I completed my Ph.D. dissertation – A History of Academic Industrial Relations in Australia. During the 1980s and 1990s, I researched, and coordinated, and lectured industrial relations (mainly undergraduate. Then I had a few years in leadership/ management roles, Head of School, Acting Dean, Director of International Studies, before shifting back into the History Department. I was also elected as Chair. Academic Senate a senior role I held for six years (the maximum term). Then in 2015, I returned to a full-time academic role, researching in a range of fields and teaching undergraduate history. In that time I have seen numerous changes sweeping through our university (and many others), changes which are destroying many of the important aspects of academia, such as academic freedom and academic governance, by and for, academics. My research has been rather eclectic – I have also written on the Australian steel industry, industrial relations, history of women, workplace bullying, and academic governance. I am currently writing on employers and workplace health and safety, especially with regard to industrial manslaughter. I would love to write more biographies because I believe biography can offer important insights not readily available in general histories.

What was your biggest challenge in researching the life of Walter Polakov? What attracted you?

I became interested in Polakov in the 1990s. An august colleague, Chris Nyland, had been researching scientific management for some years, and had obtained full access to Bulletin of the Taylor Society (now easily attainable given the internet, but not so much in the early 1990s). I was taken with the debates – the openness and collegiality (albeit, with undercurrents of personal tension!). What was a defining moment for me was to find Polakov propounding his ideas couched in primitive Marxist terms. I had seen signs of Progressivism in the debates but Polakov’s proclamations were something else, and, as a good ‘lefty’, I was hooked! All those years I had administrative / leadership roles, I could not do much research writing, but I could collect material, and my interest never waned.

The biggest challenges were first, that searching for, collection of material and secondly getting anyone interested in the paradox of the socialist scientific management. The great management historian, Daniel Wren, had written briefly of Polakov in 1980, and Nyland had mentioned him in some of his many works on scientific management, but there was very little available material. So those 15-20 years of searching and collecting in likely and unlikely places was a major challenge – especially from the far-distant Antipodes! Even when I had a basic story, many management history scholars were not interested because (a) it was about socialism and (b) it contradicted mainstream ideas that scientific management / Taylorism was unrelentingly bad for workers. Questioning the hegemon is never easy!

How would you define scientific management and to what extent do you consider it inherently anti-worker? Do you see any myths in management studies about this?

Scientific management is an ideology or set of principles about the use of people, equipment, and resources, at the workplace, industry, or nation. Central to that ideology are the importance of the application of research and the sciences to understand, first, WHAT is happening. That is very important – you cannot hope to manage scientifically if you do not understand what is being done. Second, HOW can the workplace, industry, or nation be improved? This requires measurement and investigation so that the scientific manager knows how to maximize equipment and resources and the working lives of workers. Thirdly, continuing measuring and monitoring to ensure that the best outcomes continue to be achieved. These principles stand in contrast to those who manage by whimsy, or “rule of thumb”, or simply on the basis of unquestioned managerial prerogative.

For many scholars in management, sociology, and labor history, scientific management is about deskilling, control, and exploitation of workers. I reject that strongly. There is no doubt that the notions of investigation, research, measurement and monitoring can be used for ill, but that was definitely contrary to the views of the Taylor Society and even Taylor himself. It is easy to pull out a few choice quotes from Taylor – but they are a-contextual and certainly not what Polakov and his fellow Taylor Society members thought.

Nevertheless less these remain the most immovable of myths outside of management history.

Which Taylor Society members do you think are most understudied?

Mary Van Kleeck (who made several trips to the Soviet Union and who was a union leader and a practical scholar, but was emphatic in her support of the Taylor Society.)

Henry Laurence Gantt (there is a thorough biography by Alford but it somewhat hagiographical, and skims over important aspects of Gantt’s life.)

Harlow Person (long-time director of the Taylor Society until it was taken over by the managerialists in the late 1930s)

Carl Barth (dour socialist mathematician whose advancements on slide rule technology were important for giving rigor to scientific management investigation)

King Hathaway and Robert Wolf were interesting and I have always been fascinated by Robert Valentine and the respect he was accorded in the Taylor Society, given his role in the Hoxie Report, but he died shortly after he presented his paper on Efficiency and Consent to the Taylor Society.

Why did some Taylor Society members turn against the market and the institution of private property? How did their views on worker autonomy and participation in management evolve?

The scientific managers gave what they saw as science, their greatest priority (research what is happening, what should happen, and how can we be sure it continues the best that can be done). That did not begin with an overt rejection of the market. Rather, it was simply that markets (and ‘financiers’) gave little value to science in management, to the best use of resources, equipment, and people. I am not sure that all scientific managers agreed with Polakov (except perhaps Van Kleeck and Barth?) on the generalised disgust with the market and private property, and Polakov himself always owned property.

Was there an orthodoxy in the Taylor Society, a plurality of views, or both?

Taylor Society debates (e.g. the one in the book over Drury’s paper, or another one mentioned over Valentine’s ‘Efficiency and Consent’ paper) suggest there was a plurality of ideas (political ideologies, social aspirations, values), but an unflinching commitment to science in management which of itself was an ideology.

To what extent can Polakov’s concern with energy and resource efficiency be of interest to ecological or environmental politics today?

I would have liked to have spent more time on Polakov’s commitment to energy and resource efficiency. Some of my readers have argued his greatest achievements were in raising issues of wastage of resource, and in these times with priority given to energy efficiency, Polakov’s insights and arguments offer valuable possibilities.

What effect did The Red Scares have on Polakov’s ability to work as an engineer or scientific manager? Is there anything you think Polakov’s treatment by the FBI can teach socialist technical specialists today?

My own belief is that one reason Polakov focussed on his engineering/management consultancy work was precisely that he could see what happened to activists, especially activist Russians, 1000s of whom were arrested. As well the so-called Red Ark that extradited many Russians, including Emma Goldman would also have influenced how he saw himself.

It would be hard to guess what the FBI is looking for today. The FBI under J Edgar Hoover was very focussed on socialists and communists because Hoover himself hated them. This is evident in the treatment of socialists compared with some pretty horrendous fascists, white supremacists, and the like.

Polakov returned from Russia after a relatively short tenure, how did his experiences there shape his views on socialism and political organization more broadly? How did he feel about Leninism and Bolshevik ideology?

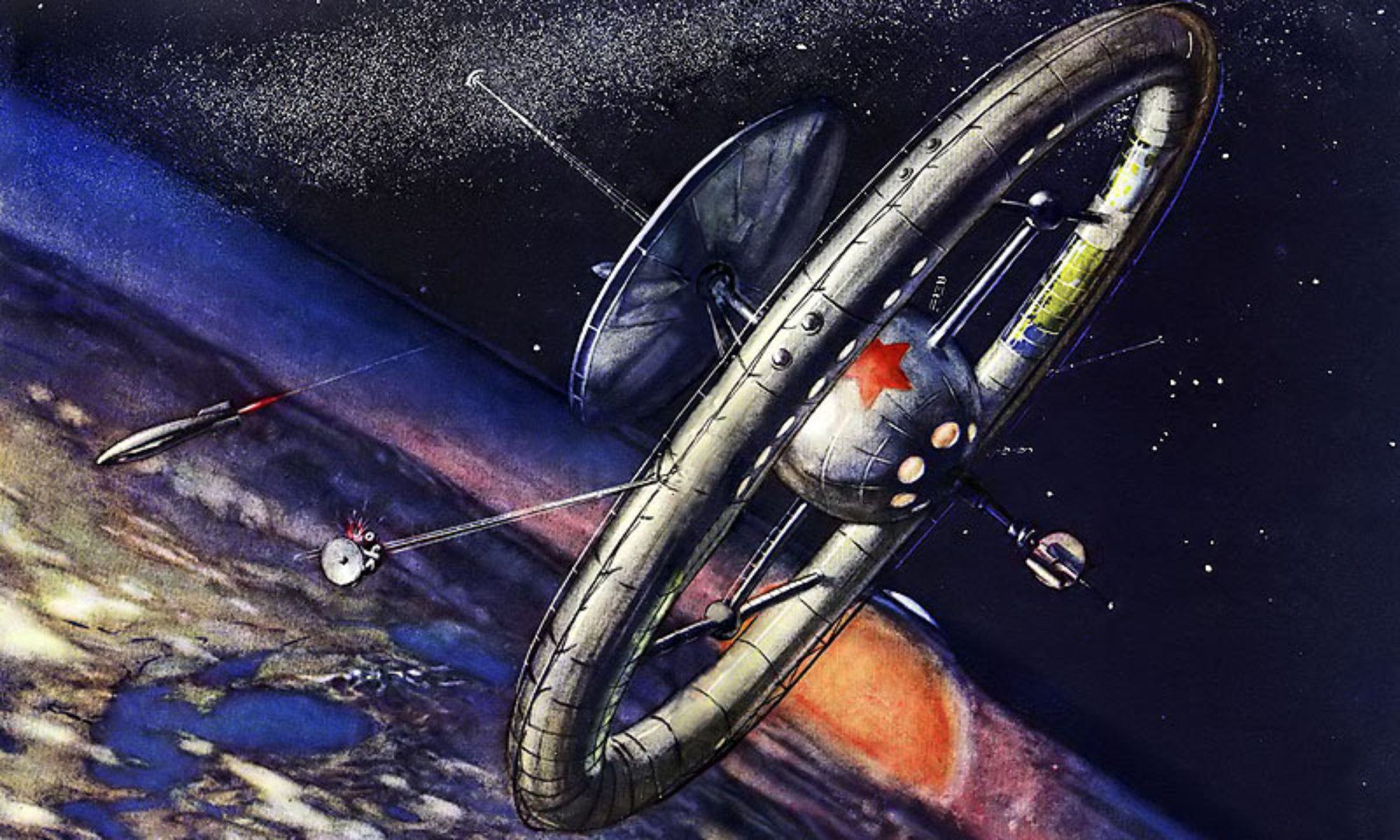

We have no way of knowing how he felt – unless we had his papers which I am guessing were destroyed long ago. In the book, I tried to project my own interpretation that he felt conflicted about the Soviet Union under Stalin. He wanted communism to work – but he could see the flaws and had serious misgivings. In some respects, his perspective was useful because he was there at the request of Vesankha. It is likely he did not get the special tours of some contractors or visitor from USA.

I am not sure re Bolshevism and Leninism. Most of his ideals seemed to come straight from Marx – and from anti-revisionists with Luxemburg such as Bebel.

What can Polakov’s experience helping to organize Soviet industry tell us about life in the USSR and this attempt to create socialism in the workplace? What was the relationship between Polakov and Soviet Taylorists like Alexei Gastev?

Even under socialism, production needs management – and Polakov was the first to say so. On the other hand, I cite times when he found the Russian managers problematic and resistant to change. He circumvented the managers’ unhelpfulness by taking his questions/requirements to workers’ committees. Polakov, who had been a practicing scientific manager for over twenty years when he came to the Soviet Union, was clearly more flexible and perhaps also more democratic than Gastev. (This question deserves much further exploration!)

Can you please explain what a Gantt chart is and why it was so revolutionary? How did its introduction to Russia by Polakov impact the organization of production?

A Gantt chart is simply a visual plan of a project from conception to conclusion, and what is expected of equipment, resources, workers, and managers. In other words, the Gantt chart seeks to record ideal outcomes of all the variables of production, and then the actual outcomes as well. By monitoring all the variables, it becomes clear where problems may be equipment or power, for example, and helps workers and their managers monitor effectiveness. It was “revolutionary” because most production had previously been rule-of-thumb or ‘flying-by-the seat-of-your-pants’. As well it offered transparency – again something that the hierarchical Them v Us American businesses had avoided.

To be honest it would be hard to see almost any impact of Polakov’s work on production in the Soviet Union. I understand some Russian colleagues have explored this. I hope they can find archival material that would confirm or deny impact, but my guess is, sadly his sojourn in the USSR changed little. On the other hand there is evidence of the Gantt Chart being discussed in the early 1920s – and in this respect, I believe it would have been based on a Polakov translation. But no evidence yet, sadly.

Can you explain what Technocracy Inc was and its relation to The New Machine? Would you consider the Technocracy movement elitist?

In the book I hedge around the possible links between the New Machine (19i6-1919) and the Technical Alliance (1919-1921) and then Technocracy Inc (1933 – 1930s). Certainly Polakov seems to have been on the freinges of both TA and TI – he was cited several times as a lead author in their surveys. On the other hand he never fully commited to the TA or TI. I suspect Howard Scott had something to do with – he was one of those charismatic enthusiasts whose own knowledge may not have been as great as his enthusiasms – for Technocracy or the IWW, of which he was a member. I understand from some writings that Scott tended to alienate or overwhelm people. Polakov certainly held Technocratic ideas but I think he was tempered by his socialism and his deep commitment to the scientific management practices of research into what’s happening and what’s needed and what can be done … (as well as the democratic rule of engineers!)

What role did Polakov play in the United Mineworkers Union and how did he reconcile it with scientific management philosophy?

Polakov’s scientific management philosophy was as applicable to his work in the union as it was to his work as an engineering – management consultant. That is I hope a major point of the book – that scientific management ideology is not about control and exploitation of workers, but rather using science to make work and production, the best outcome possible. The reason that Polakov was raising safety and consultation and reasonable pay/ conditions from his earliest writings (and work as a manager), was that he saw these issues as centrally important as a means to achieve the best workplace environment for workers. People are way too conditioned to think of management as a hierarchical “my-way-or-the-highway” process so that they cannot see that scientific management ideology could be equally at home in a union as in a factory.

How did Polakov’s research into workplace safety help the union? What role did Polakov have in spearheading the development of Union Healthcare plans?

I believe Polakov’s role was significant in setting up the possibilities and furnishing the data for several really major health initiatives of UMW – I need to do more research still to make unequivocal claims.

How did Polakov use the language of management and accounting to force management to take workers’ concerns seriously?

All the scientific managers knew just how to influence managers and executive managers – just explain ideas in ways that are important to them. There is no point in telling a manager about how great a worker’s life will be with the scientific management initiatives because those managers are driven by priorities of output, return on investment, and next quarter’s profit. So the scientific manager needs to talk to the plant/organisation/industry manager in terms that he (and they were almost always he) would understand and which would motivate him. In the discussion of the Taylor Society debates in the book (p.41) even the not-very-leftist Colonel Coburn argued that with scientific management “… we are finding some facts and we are putting those facts into such shape that the financial man and even the director can understand them”. In fact, the financiers who owned the plants could no longer “grind the neck of the working man with an iron heel” as a substitute for proper management. (Coburn in Drury, 1917 p. 8) It was not that Coburn was a radical, but rather he could see how the ideology of scientific management could be framed to convince the financier or executive manager that fair working conditions were more effective.

Similarly, Polakov’s engineering monographs at UMW, and his paper to the employer-oriented National Safety Council sought to show employers how much the cost of accidents was a problem for employers. All his books emphasized the same things – he was writing to convince managers and the public who might influence managers that his scientific management initiatives of improved consultation, work, and safety conditions were about benefiting business – even as hr slipped in semi-plagiarised bits from Capital Vol 1!!

47 Replies to “Walter Polakov and the Hidden History of Socialist Scientific Management”

Comments are closed.