Throughout the United States, revolt against police violence and the state has broken out in response to the callous murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police. To help contribute to this outbreak of militancy, we have published these words of advice on successful protest from Ahmed Nada, a veteran of the Egyptian protest movements in 2011, 2012, and 2013.

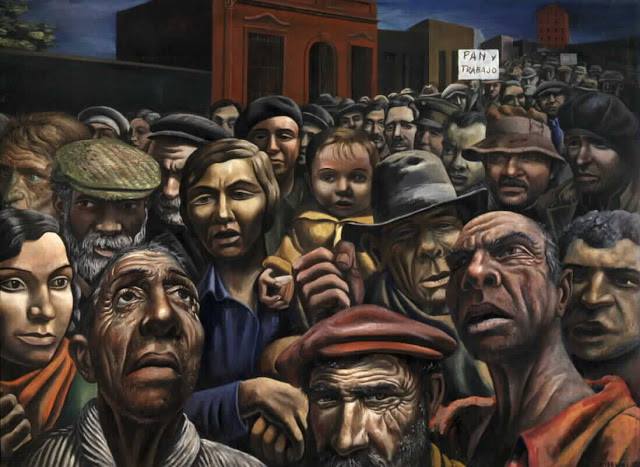

Protests are chaotic: they often begin suddenly and with minimal prior organization with the embers of a spark few if any could’ve seen coming, an enraptured anger manifesting in people taking to the streets to vent their frustration. Occasionally, this can occur in the backdrop of a movement with a couple thousand followers on a social media platform with an event a few hundred promised to attend, of whom maybe tens did. None of that matters when the first fires are set, when the first rubber bullets are fired, or when the first police car plows through a protester: a protest becomes a war where the participants are naturally unequal, with organized police on one side, and the other only vaguely organized in the best of cases. I was involved in several protests, which ranged from completely unorganized, to planned months in advance – though in the heat of the moment, much of the organization becomes moot, forgotten, or miscommunicated. Such is the nature of attempting to create order where no hierarchy exists, between people who, by their existence within the protest, are not in the best position of their lives. The financially capable would not risk to protest unless their financial capabilities have been thoroughly eroded – protesters have very little left to lose, in most cases. These people, the forgotten, the downtrodden, the distraught, are confused, in some stage of shock, and enveloped in a cloud of tear gas. This exact moment, the moment where a protest’s reality crystallizes, where the romantic image of chanting in a manicured square flanked by boulevards lined with like-minded revolutionaries evaporates into a cloud of white gas best described as a liquid attempting to drown you where you stand, and gives way to the harsh reality of meaningful protest. This is the moment that will make or break a protest, because it is the moment when those who can’t bear it will leave, and those who can will rally behind the first person lucid enough to lead anyone to do anything, and they will often be the least prepared and most vocal.

I have lived this moment more times than I can remember, or care to remember. There is no romance in protest except for the people who never experience it, who have the fortune of reading about it later on, or who feel the misfortune of reading about its failure. My first real protest, the first where I saw someone die, I was twelve years old. I wouldn’t turn thirteen for another seven months, and I had no choice in the matter. I had no convictions, no revolutionary fervour, no ideals; I wasn’t swept up in the moment, a mud-faced child in a painting drawn by a Frenchman a hundred years later. I was in the streets because I was one of a handful of people in my building who weren’t retirees. I was given a broomhandle that was later upgraded to a machete and told to defend my area or risk being killed by the people who were firing bullets on the other side of town; whether they were ‘thugs’ or cops didn’t matter. I was twelve years old and it was fight or fight, because even if fighting meant death, flight meant death too. In a way, I was fortunate to have been that young; my later-diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder was treated earlier than most of the others, and I was able to internalize lessons more quickly, because I had no solid conception of how the world worked. This is what allowed me to begin to organize two years later, as one of the stewards of those more organized, less chaotic protests, aged two months away from fifteen. I have had the misfortune of witnessing protests from the perspective of a child swept up in them unwillingly, and the perspective of a teenage, bravado-filled organizer who believes everything is figured out until it isn’t. I write this not as an analysis, nor as a parable, but as an open letter to protesters, especially in America given the current circumstances. I stand in solidarity with the protesters in Minneapolis, Columbus, and any other cities who have had enough with constrained silence, and if anyone involved in those protests or future protests is reading this, I hope it can help you. My aim with this piece is that you come out of it with a better understanding of how protests work in the moment, lest you end up in one of them, or seek to organize one. If you remember nothing else, however, I hope you remember to send any children involved in the protest home. If you can’t attend a protest without bringing your child with you, then let staying home with your child be your praxis; children have no place in protests, for their sake.

It must be acknowledged that my experience is not fully applicable to Americans: for one, Egypt’s urban planning is radically different. Furthermore, during the early 2010’s in a country held back technologically, protests, where the internet and all communications have been cut off, are a very different proposition to the interconnected – and easy to track – world of the present. With this, my first and foremost tip for you, the would-be protester, is to turn location services off on your phone prior to leaving your home, and turn your phone itself off before you set off toward the protest. You most likely don’t need to worry about being tracked; if your identity is known, the authorities have other ways of finding you. Turning off your phone is a benefit for your fellow protesters, because location services and WiFi connections, particularly municipal WiFi, are an excellent way of gauging how many protesters exist and where they exist. We got by without phones, we had to adapt, because the government shut down every communications network entirely, and one of the key methods of adaptation was using relays. A relay, in this case, is essentially a person tasked with maintaining a set – ballparked – distance from another relay. They can be organizers, ideally they are, but they can be anyone with a keen sense of where they are relative to others; tall people, rejoice, this is your praxis. A relay network allows organizers or torch-bearing leaders forged from the clouds of the scene I described to send and receive information, especially orders, without the need for any means of communication apart from a soon-to-be worn-out throat. For anyone wondering about social media or the like, forget that it exists during a protest. Social media is not the driver of nor the key to a revolution, it is at best useful for organizing beforehand and agreeing on a meeting point or coordinating with other organizers, but is of no use to you during a protest apart from as a distraction; that isn’t to discount the use of organizing with other protests, though that’s a bit down the line.

Organizers are your key source of communication, both with the other protesters – who throughout this process will be, at best, confused and anxious, and at worst rampaging with zeal – and with other organizers. If you see yourself as an organizer, or find yourself in a position of sudden power during a protest, your job is to watch for your protest’s problems from within and without: the police are not your only enemy. Your enemies are the police, anxiety, injuries, unstable troublemakers within your ranks, perverts who would rather grope other protesters, and hunger – I hope to address each of these. The easiest and most futile-feeling, time-consuming, and infuriating to deal with are the troublemakers. They will exist in every protest, even the most well-organized one, because opportunists are fostered by capitalism and indoctrinated from birth to seek their own benefit. They are unfortunate, but you need not humor them for the sake of numbers: kick them to the curb, leave them behind, and be alert for any more in your midst. Do so as early as possible, because time and stamina are not a luxury you can afford to squander. Harassers from within aren’t the only thorn in your side, however, because with the chaos of a protest will come injuries, whether inflicted by the cops, gravity, or the inertia of the horde. Ensure that anyone – anyone – with any – any – medical knowledge is designated as a medic and sent to anyone who needs medical attention. There are guides all over the internet for providing field aid, and their writers are more qualified than I will ever be, though I would caution against one tip they may give: avoid the temptation to clearly label medics. I have seen too many clearly-labeled medics get shot by snipers who have never existed, using rifles that were never obtained. Know your medics, make sure every organizer is aware of where medics are and where medics are needed, and if you have the fortune of a stable, secure central location to ferry the wounded to, ensure it is defended and secure. Non-medics who are strong enough to carry the wounded safely without inflicting further injuries should be made to do so; any help that isn’t counter-productive should be welcome. The main thing to remember if you are an organizer, relay, or medic is to avoid hesitation. I cannot stress this enough: things develop quickly during protests, and they will not be fun, nor will they be calm. Time is not a luxury you can waste.

Organizers’ most difficult job is the same as the riot police’s most difficult job: controlling the crowd. As a rule of thumb, if you can’t communicate it to a five year old through a game of telephone played in a warzone inside of an echoy aluminum barrel, you can’t communicate it to a crowd of protesters. Keep orders simple, sensible, and repetitive. When riot police haven’t arrived yet, have protesters fan out and space out your organizers. This allows you to claim more space and intimidate the police’s first responders. It can be tempting to maintain this shape, because it looks the most impressive on camera, but that is a reporter’s concern, not yours. When riot police arrive, tighten up. Every organizer should repeat this: tighten up, get closer, tighten up, get closer. Any stragglers will be enveloped by riot police as soon as they stray from the group. You must be keenly aware of how the police work, particularly riot police. There are several resources online as to how your local riot police operate, though they generally follow the same few tactics. You can listen to their scanners to get a read on what they’ll do, but note that they’re often aware that you can hear them. There are methods of listening to ‘secure’ channels on walkie-talkies that are as simple as hooking up a phone with a headphone jack to a pair of headphones and tuning AM and FM frequencies – usually the higher bands for AM, lower for FM – until you hear chatter. That said, some cops are aware of this too, and will call each other on phones instead. In that case, your only remaining methods would open you up to FBI interrogation, so I would suggest avoiding them entirely for the sake of your own safety.

Regardless of their statements of intent, most riot police begin by attempting to intimidate protesters. They will have their most heavily-armored officers at the front, and they will first stand in front of the protest in a line, portraying the same statement of intent that Roman Legionnaires would give to protesters two millennia ago: we are more organized than you, we have better equipment, and this isn’t our first rodeo. Some protesters will give in to the intimidation, whether by leaving the protest altogether – which will lead to their envelopment by the armored line to get arrested on the other side – or by charging at it head-first only to be enveloped by it and beaten. This is the second crucial moment of a protest: the arrival of the enemy. If you have the organization necessary to form into a line of protesters, do so. You have the numbers advantage, they don’t. By forming a line against theirs, by enveloping your wounded chargers into your own line to be treated, you send the police a statement of your own: we are organized, and where we lack in equipment, we make up for it in bodies. You don’t have to believe in this statement, yourself, nor do any of the other protesters; the cops will, and it will shake them. The officers at the front are often trained not to show when they’re shaken, but listen to the scanners and you’ll hear their will begin to break – they can’t leave by choice, and it’ll show if you press them hard enough. The staple weapons of riot police, the batons – electrified or otherwise – and the shields, are not the concern of most protesters; only the ones unfortunate enough to be at the edge will ever even see them. The weapon most protesters will feel, however, is tear gas. When the first canisters are fired, they will be aimed roughly into the middle of the crowd if the cops can see it, or downrange above the first line of protesters. When you see those silver canisters, throw them back at them if you can, or throw them as far away from the protest as you possibly can; instruct others to do the same if they can hear you. The easiest method I’m aware of to combat the effects of tear gas are to hold a rag up near – but not on – your face with a capful of Pepsi (not sponsored, I swear) poured onto it as evenly as possible. It should help you weather it; in the age of COVID, a surgical mask with a capful on it will also work, but make sure it doesn’t touch your face because it’s sticky and may restrict breathing.

The cops in armor may be the most intimidating, but they aren’t the most dangerous: the mounties are. Mounted cops have been a staple of riot control since the first revolution in recorded human history, and for good reason: they break through lines with the force of a several-tonne creature carrying an oft-padded, well-armed cop who can strike anyone who poses any semblance of a threat. They are the final boss of protests – until the army gets involved, that is – and they have the potential to derail any level of organization you’ve reached. The key to stopping them is not to attempt to stop them: make way for the cavalry, then surround them. The horse is confused, anxious, and erratic, and its rider can’t attack in every direction. Let the horse into the crowd, envelop it into the crowd, pull the mountie off the horse, and throw them back into the riot police’s face. Show the mounties mercy, because this will demoralize the police further, and will avoid radicalizing the cops into attacking more vigorously. The ‘mounties’ we faced in 2011 wielded swords and assault rifles, the ones you will face will have batons. You can and will survive them if you know how to mitigate their effects. When mounties appear, prepare the medics for the influx of injured. Replenish your lines, and as soon as you envelop the horse, strengthen your line against the riot police. As protesters, you must channel the Persian Immortals and use your numbers to portray invincibility, as cheesy as that sounds. The single most effective charge a mountie can perform is across a road median, because it is often elevated and grassy, where the horse has the inertia and landscape advantage against protesters. Roads with medians were originally conceived to prevent another Paris uprising, for just this reason. They are also more difficult to hold because they are wider. Wide boulevards are not the mark of a city built for opulence, they are the mark of a city prepared to face protesters with violence. You need to know your city and know your protest location(s).

The most common tactic in a protest is to have one central protest in the heart of the city – a main square, a wide boulevard, a main avenue or thoroughfare – because that allows numbers to be portrayed in their most visible, most evident form. This is great for photo-ops, not so much for actual defensibility. The vast majority of American cities, especially ones built after Washington, DC, the first city where the United States Government consciously chose to build with protests in mind – wide boulevards, interconnected squares with huge empty greenspace, et cetera – are built to make a lasting protest as difficult as possible. Main roads, intersections, and squares have several wide roads leading toward them, few – if any – barriers already existing, and openings for police to pour in from on several sides. Police precincts will often be situated on main roads, both to ensure they are difficult to cut off, and to ensure they can reinforce police and rearm them easily. American cities, in fact most western cities, are built to be hostile to protests; the urban planning is inherently violent. Your worst nightmare in a protest is to end up where we ended up in 2011 at the beginning: surrounded on all sides. You have numbers, you will always have the numbers advantage, but numbers are meaningless when you’re surrounded, especially if you’re choked for supplies. The best and most difficult solution to this is to stage several protests, or fan your protests out to cover several squares/intersections, in order to project power over the streets in between. Cops are not dumb, they won’t risk getting surrounded themselves. If you control every square or intersection around a police precinct, that precinct has been, for all intents and purposes, neutralized. Maintaining several locations allows you to reinforce them and create a two-front battle if police attack from the side you already have protesters on elsewhere, and they are keenly aware of this, and will be denied that avenue of attack.

In order to maintain coordination between different protests, at least one organizer must risk being the point of communication. This is dangerous, though you need not deal with the same ferrying back and forth we had to do, because your communications are open – for now, at least. The organizers who communicate must stay in the know and up to date, but must stay far from the front line. Their identity must be protected at all costs, along with as many identities as you can protect. Don’t share photos that haven’t blurred identifying features – faces, clothing, et al – and don’t share names nor specific locations of organizers. As much as possible, limit communication with the outside world, especially for frivolous reasons. You can boast later, do not waste time. Time is not a resource you can afford to waste. It isn’t the only resource, however, and the next step once an area has been secured is to secure resources: food, water, medicine, contraceptives – yes, you’ll need those just in case – you will need all of the resources you can get. Don’t worry about being branded as ‘looters’, you will be branded as looting thugs either way. The main thing to remember is to avoid harming anyone in the process: the workers are on your side, and you are on theirs. We had the fortune of our comrades in a KFC right on Tahrir Square providing us with food, water, and Pepsi (not sponsored, it’s just more effective than Coke in my experience, sorry) for tear gas protection. We also had the fortune of pharmacists joining us. Should you not have these boons, stores aren’t that hard to raid for supplies. I would suggest avoiding causing too much damage, because corporate doesn’t have to fix it, some poor employee does; remember the human who has to deal with the fallout of your actions, and try to remind fellow protesters as much as you can. Once resources have been gathered, you need to construct barricades. SUVs, large, new-model pick-up trucks, these can be flipped onto their side with minimal effort from a half dozen people, and are very hard to move afterward. Vans can be used for heated sleeping spots, as can buses. Set up tents if you can, especially if you’re in an area with a nice enough climate. You will then deal with the next challenge: the first night.

The first night is the hardest. People will leave. People will have to stay up on nothing but caffeine (don’t drink all the Pepsi; not sponsored) to defend those who sleep. People will get horny, get fearful, or cry. It’s normal. Some people may play music, sing, or write. It will be incoherent, but the incoherence can be beautiful. The people who make it through the first night are easier to organize the next day. The night is also when you are most likely to get raided by the riot police. Organizers should sleep only in shifts, two or three hours at a time, and maintain relays as much as possible. If you have multiple protests going, coordinate to make sure no protest is fully asleep at any point. An integral part of the first night is to talk to the people who break down, because that may be their breaking point. If you are not yet fully surrounded and they can leave safely, they should be allowed to; a protest is not compulsory, and being allowed to leave is what personally radicalized me, among others. Do not forget your ideals for the sake of winning a battle; remind other organizers of that too. The first night will be ideologically challenging, because it is when you will first get to speak coherently to others, especially other organizers, and I guarantee you that you run the gamut of ideologies but share a common desperation and exasperation. I have fought alongside fellow communists, anarchists, liberals, conservatives – yes, they’re odd – and even Islamists. The alliance is tenuous, it has an expiration date, and it is uncomfortable for everyone involved, but you are better with them in the moment. Your protest is not a movement, even if it started as part of one. If your protest is successful, you will most likely be betrayed by one or all of the groups you have allied yourself to, willingly or otherwise. You will find yourself in the same ranks as people you despise, because you share a common desperation, or otherwise you wouldn’t be there. Break bread together and sleep under each other’s watch, because you are on the same side for now. You don’t need to make enemies, because you all have enemies outside the tent, van, or bus, and they won’t hesitate to break you.

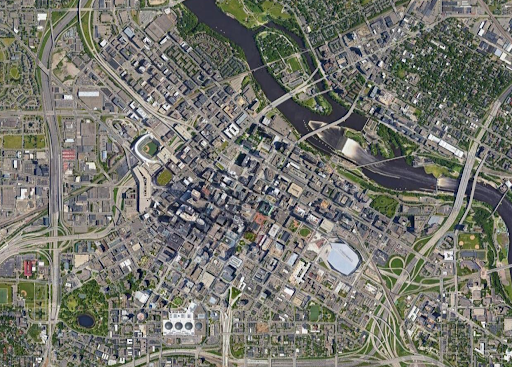

A major aspect to breaking you, especially long-term, or before you can ever hunker down, is the aforementioned urban planning. Highways were designed to encircle the city and enable the military to enter the city center as quickly as possible; destroying black communities was a bonus, and the tarmac, gas, and car companies were all too happy to fund it all. A highway is a death sentence. You can hold it for a time – focus on the ramps, they’re more manageable – but it will be your doom if left open, and if the army enters the fray. We were fortunate in 2011 and 2013, the army was on our side, but in 2012 it wasn’t, and that led to a rift within the army itself, but only after they plowed APCs through our lines and fired live rounds into us. You need the army, but if it’s not on your side, you have just met the final boss of a protest. Flee onto sidestreets, barricade them with tipped-over cars, use buildings to stage, sleep, and store supplies; barricade the doors and roof access, but keep an eye on rooftops – don’t stay on rooftops, they’re too open. You want to create scenarios where, as said before, you can encircle the police if they attempt to attack you from any side. Cities with grid plans were built to counteract this by providing no clear sidestreets, having several avenues of attack leading to the same areas, and having wide streets that are difficult to barricade. Cities like Minneapolis are especially problematic due to their pedestrian bridges, which provide easy alternate routes for police. The deck is stacked against you by the hostile planning of your city, more so than it was against us. Cairo is divided by a river, and bridges are choke points the police would rather not get stuck on, nor should you. The main streets leading into downtown Cairo have squares – roundabouts – where the narrow roads meet, which, if held, can protect Tahrir Square’s central location and force the police to attack from outside of the city center, in only a few manageable directions, particularly if the only highway leading into the heart of the city is controlled. If your city is not a grid, and you have characteristics similar to that, or better, then you only have everything else I’ve mentioned to worry about.

Apart from the logistics and chaos of protests, the hardest part is the purpose and impact of it all. While organizing beforehand is often a boon underestimated by the media and casual observers, you cannot organize the aftermath any more than you can organize the aftermath of a hurricane. Alliances will break whether you achieve your goal or the protest gets crushed, and each splinter of the alliance – and possibly within those once-allied factions – will face a different set of consequences and will have a different view of the events and their aftermath. There has never been and will never be a protest of more than a few thousand people with a consensus over the aftermath of it all because fundamentally, the only unifying factor you all had was being fed up and lacking much to lose. This is not to say that you can’t shape the aftermath, however, and this is where the real power of organization enters the fray: continual pressure. You will have failures, and you will have to learn from them. You will have successes snatched away from you by some of the groups you fought alongside; we had 2011 snatched away from us by the army, then by Islamists, both of whom sought to imprison us for our trouble. The key is not in dwelling on your failures, but using them to propel you forward. The single greatest weapon you have is frustration because a protest is the end result of a swelling mass of frustration. The worse it gets, the closer you get to a nationwide breaking point, but by the same token, the harder it gets to organize effectively. Our worst loss was not in 2011 when we had our revolution snatched from us, it was in 2012 when we organized a protest entirely from scratch, entirely made up of like-minded groups, only to have the army crush us in an instant. It was the worst loss because it had no lessons for us apart from one, which I will relay: you need armament on your side, and the greatest armament you can get is by splitting the army. This is easier said than done, but it is very worth it. Often, the army itself will begin to split when they’re forced to shoot their neighbors because they aren’t as drilled into murder as the police are; they aren’t built for suppression… usually.

The key to gaining support is not retweets, nor is it op-eds, nor is it sucking up to the media with peaceful protests that achieve nothing apart from spend the entire national surplus of frustration on futility: the key is continual pressure. We succeeded in 2011 and had it stolen from us, so we protested again in 2012 and got crushed, so we rode the momentum of the frustration to a protest involving one-third of the country’s population in 2013, and that cannot be ignored as easily as a couple million people crushed under an APC. You will have endless failure until you don’t, and that moment will be equal parts surreal and terrifying, because you have no control how any protest ends nor where it goes from there until you begin the next one, and that is true of your successes, more-so than your failures. Success breeds factions that seek to profit off of it, whether monetarily or through power dynamics, and you will have to contend with that. Build your ally base out of factions you know you can trust. Avoid allies of convenience outside of protests themselves, and maintain strong relationships with factions that can’t protest as easily as you can; the unions, the people working three jobs, the people on overtime graveyard shifts who can’t risk their credit rating falling any more than it has. These are your base, these are your allies when you succeed, and they are how you channel popular pressure into legitimate change, because you are a protester, you are illegitimate by your very nature, but you are the hammer of the legitimate. Protest until you succeed, counter-protest when – not if – your once-allies ride your successes for their own benefit, and above all, do not surrender for the sake of civility, legitimacy, nor platitudes of peace; your fallen comrades were given none of the leeway these concepts imply, and you should not grant your enemies this leeway either. Protesting is not an easy path, nor is it a bloodless one; the myth of the peaceful social media protest was created to give you false hope in pointless action. Remain steadfast in your opposition, maintain organizers who can harden with your failures and maintain stability with your successes, and don’t let up, for the sake of your human losses. Whether the protest fizzles out, is crushed, or achieves its goal, you are in a pantheon of a minority of humanity who risked everything for the sake of change, and that is the only romance you will ever need in a protest. Good luck, comrade.