Richard Hunsinger & Nathan Eisenberg give an in-depth analysis of the current crisis where economic breakdown, pandemic, and mass revolt collide into a historic conjuncture that will forever shape the trajectory of world events.

Disruption

We are running out of places to keep the bodies. In Detroit, a hospital resorted to stacking up the dead on top of each other in a room usually used for sleep studies. In New York, the epicenter of the pandemic where, for a week in April, someone died of COVID-19 every 3 minutes, a fleet of refrigeration trucks is enabling interment in parking lots for overcrowded hospitals. The chair of New York’s City Council health committee, publicly stated that they were preparing contingency plans, per a 2016 “fatality surge” study, to dig mass graves in a public park. The resulting moral backlash prompted Mayor de Blasio to deny any such plans would be carried out, but he would go on to emphasize the necessity for mass graves on Hart Island, an old potter’s field in the Bronx long home to the unclaimed corpses of the indigent, which has quintupled its monthly intake of bodies. As is protocol, the excess demand for the work of burying bodies on the island is being met with the use of prison labor from Rikers Island, which itself has the highest infection rate in the world. The situation in private funeral homes is similarly dire. Dozens of corpses were recently found rotting in U-Hauls outside a funeral home in New York. In Ecuador, there are cases of bodies being wrapped in plastic and left on the sidewalk for days before strained hospitals can send an ambulance, prompting engineers in Colombia to come to their aid by developing hospital beds that transform into coffins. Mass graves are cropping up across the world, in Ukraine, in Iran, in Brazil. A man in Manaus, Brazil, interviewed by a Guardian reporter while watching his mother’s coffin be lowered into a trench alongside 20 others, despaired, “They were just dumped there like dogs. What are our lives worth now? Nothing.”

Such macabre undertakings point to a sense that this pandemic is unmasking the real immanent content of capitalist society in all its uncaring austerity and banal cruelty. The simple fact, now visible to anyone forced to work without PPE or handing over rent payments from dwindling savings with no horizon of replenishment, is that capitalist social relations cannot sustain human life, that their own perpetuation requires our mass endangerment. The exceptional nature of these present circumstances show the degree to which basic subsistence has been whittled down through protracted class struggles to the point where it is more or less precisely calibrated to merely maintain bare social coherence, leaving the system in a place where it cannot endure significant disruption. This fragility, which routinely exposes proletarians to the most brutal deprivations, is now generalizing across previously secure populations, emanating directly from capitalism’s constitutive contradictions, contradictions between the human fabric that serves as labor-power inputs and the circuitous process of capital accumulation that it animates. All creative activity is organized for this end, no matter the consequences. In the current moment, an accumulation of consequences, previously arrested and deferred, are now spilling forth all at once, like a burst clot. Blood is pooling in the tissues of the social body; the airways are blocked.

If we seek to give an honest diagnosis of the injury and trace the symptoms back to determining conditions, we find an advanced necrosis. This necrosis has many appearances. Capital overaccumulation, taking the form of frantic and increasingly fictitious credit-money markets, on the one hand, and a build-up of industrial capacity far in excess of what is profitable to operate, resulting in chronic overproduction, on the other. Intertwined with this surplus capital are the masses of surplus populations, an explosion in the landless proletariat in absolute numbers colliding with depressed capital that can profitably exploit only a relatively waning subset, rendering the remaining masses superfluous and subject to the diverse tortures of increasing lumpenization. The declining social wage fund that results from this is managed and calibrated with protracted disinvestment in public welfare infrastructure, now most spectacularly in the arena of public health, constituting an outright abandonment of social reproduction. The result has been a managed decline, never so precipitous as to descend fully into social chaos or break the holding pattern, except in punctuated moments that have proven containable in time. While these morbid symptoms of the capitalist mode of production sputtering under its own weight metastasized, the rot was allowed to fester through a palliative nurturance designed to mask it.

We are now witnessing a precipitous collapse of some kind, novel in many of its features, even if it is not yet recognizable as the eschaton many communists (at least implicitly) imagine. Several prominent left-liberal commentators have formed a chorus, which always seems to be at-hand during such a spectacle, theorizing the transformative potential of the pandemic, tending to speculate with unwarranted utopian optimism. Slavoj Žižek activated his Verso showerthought pipeline to crank out a book of impressionistic digressions on the virus, musing that coronavirus is a “perfect storm” that “gives a new chance to communism.” Of course, this would not be the “old-style communism”, but rather the communism of the World Health Organization, where we “mobilize, coordinate, and so on…”; in other words, the banal mechanisms of liberal governance (though as we will see, even this is too much to ask anyway). He makes a vaguely humanist point about how our shared biological vulnerability generates some basic solidarity, citing how even the state of Israel “immediately” moved to help Palestinians, following the logic that “if one group is affected, the other will also inevitably suffer.” This claim is, of course, absurd, as a cursory glance at recent news reveals: Israeli police shut down a testing clinic set up by the Palestinian Authority in East Jerusalem, settler violence against Palestinians in the West Bank increased 78% in late March, house seizures and IDF abuses only worsened and plans to annex the West Bank continue uninterrupted. In a significantly more sober and careful appraisal of the situation, looking at India, Arundhati Roy still characterizes the pandemic, in a turn of phrase reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s Janus-faced figure of a historical juncture, as a portal through which we might step into a better world. The environmental economist Simon Mair finds hope in the revelatory nature of the crisis, as the failures of “market neoliberalism” are bared for all to see, and maps out four futures after the pandemic, the boldest horizon of which is a program of nationalization plus “new democratic structures.” This “democratic antidote” appears frequently in a context notably distanced from the violence of the present. In a call to “socialize central bank planning,” Benjamin Braun writes on behalf of the “Progressive International” of a democratic vision for finance. Amidst the muddled juggling of abstractions, democracy, capitalism, and technocracy are posited in an assumed possibility of harmonious balance; a goldilocks-esque treatment for reinvigorating capital accumulation. Echoing the wonkish dialect of Elizabeth Warren, Braun writes: “indeed, the left’s capacity to develop sophisticated, actionable economic policy blueprints is growing fast. TINA (“there is no alternative”) was yesterday — today, progressives ‘have a plan for that.’” For the supposed strength of this ideology of “the plan,” a plan of any sort is nowhere to be found outside of these aimless gestures at a remote possibility. Most importantly, the class struggle required for even these tepid evolutions is conspicuously unmentioned.

For all the aspirations to a “radical reform” embedded in the slew of prescriptions, these supposedly “realistic” invocations of new horizons of possibility continue to ring hollow. The immediacy of crisis is inevitably lost in the wish-lists of those that appear merely disappointed in power. The rose-colored glasses of the “democratic” path see opportunity conveniently devoid of context. Begging sobriety, it is critical to acknowledge that no matter where we go from here, it is in the wake of unfathomable loss. Such is the ritual of capital, a totalizing directional movement based on a logic of infinite expansion, only realized through the domination of the living by the dead in a process existing purely for its own sake. While it is true that with crisis comes contingency, and thus new possibilities, these only emerge under certain determinate conditions. In the last instance, it is in the terrain of economy, by which we enter into relations independent of our will and become bound to the social productive forces of material existence, that we ascertain the most pronounced objective shape to history. This edifice, however, merely appears objective, as an undead automaton distorting time and space at a steady interval. Our lives, the time we breathe into them, are rendered unconscious non-events by the mechanical operations of capitalist reproduction. Despite the novelty of this present crisis and the rapid pace of developments, there are trends and outcomes we can begin to apprehend with relative confidence. Critically engaging this material substratum of the economic, the fundamental base of society’s reproduction, presents us with a range of interpretation. Our intention is not to speculate or to anticipate what new reality will emerge out of this situation, but rather to demonstrate that the events and ensuing struggles of the present, despite their unprecedented scale and intensity, have clear origins. For us, this is the best way to interpret the present crisis: in context.

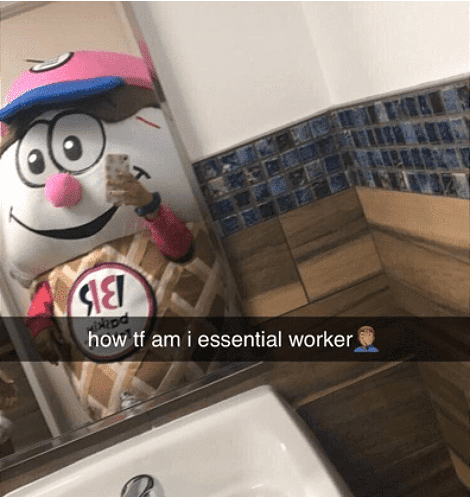

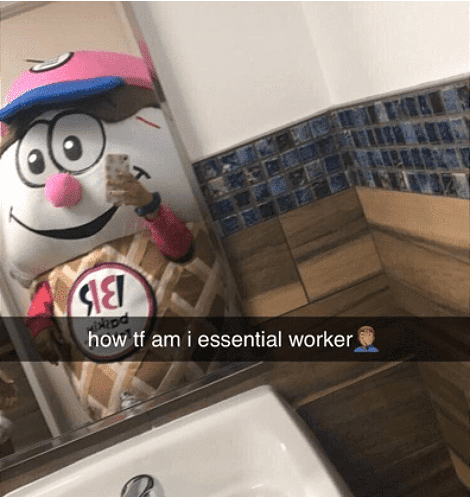

For the crisis at hand, to merely meditate on the apparent ruptures will not suffice. Despite this particularly catastrophic iteration of the onset of crisis, it fundamentally cannot be divorced from the prior dynamics of capitalist development. The pandemic acts as both disruptor and accelerant, imposing strains on an already struggling and weak global economy. Both the imminent threats of recession and pandemic having long before been present and dire. The failures of the present order bring the world as it was before into a new clarity. Necessity invigorates demands that may prove to undermine capitalism’s conditions of possibility. Social relations previously taken as fixed begin to reveal that their rigidity was in fact fast-frozen movement. The roles played in mediating these contradictions, the bourgeois classes, revealed as nothing but mere figures carved of wood: mocked-up subjects performing an empty ritual, a mockery of life largely reliant on birth lottery and sycophantic power games. It is ironic, then, that the very moment that we may not enter the world without a mask, these character-masks of our era would begin to show signs of slipping. In light of this, simply anticipating a return to “normal” seems premature. It is only through the impacts of emergent struggles that we will know what becomes possible at this juncture.

It is here that we must speak of another potential unmasking. Marx theorizes class in the abstract as defined by one’s relation to production, a crucial element of which is the functional role thus performed within the circuit of capital accumulation. Marx referred to such reified social roles as “character-masks” (Charaktermaske), which is frequently translated into English as “bearer”: subjects who are compelled to carry the process of capital accumulation forward. With the original wording, the emphasis rests more on an external construct that comes to displace the interiority of the subject: as one assumes the mask, so they assume the character. Capital, as the dominating logic of society, is otherwise indifferent to the lives of its subjects beyond adherence to this character-mask, a hazard true for any specific members of the bourgeoisie. And so he writes “As a capitalist, he is only capital personified. His soul is the soul of capital.” This near-total identification is no natural relation, of course, but a contingent one existing in a continuum of ceaseless struggle.

Of course, the two character-masks in this process, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, are not static structures, two opposites with parity, but mutually contradictory social forms locked into an antagonistic dialectic between the owning class and the class which owns nothing that has yet to be resolved. In this way, we can understand class as a matter of material compulsions embedded within the general problem of social reproduction. The proletariat is maintained as such in order for it, as a class, to fulfill its role selling labor-power, the exploitation of which is the foundation of capitalist society. Capital is more forgiving of the proletariat: if they fail to sell any labor-power, and are thus relieved of this function, they remain a proletarian. The immiseration of their position is a given in their role. The strictures of performance, however, are much more severe for the bourgeoisie. The extent to which one personifies this role in relation to production, how successfully one allows their social behavior to be subsumed into the dictates of capital, determines one’s ability to stay a member of the capitalist class. If one is caught off guard, either by allowing their workers to slack off or neglecting the growth of their profits, then one is promptly expelled from the class by their competitors, expropriated and ruined like any proletarian.

Such purges are cyclical within capitalism, as recurring economic crises brush aside the low-performing capitals and pave the way for concentration, thus allowing capital as a totality to maneuver out of its convulsions and establish accumulation anew. This secular process of consolidation brings with it qualitative shifts, such as the late-19th century emergence of monopoly capital that Lenin and Hilferding identified as the driver of imperialism, resulting today in substantially internationalized capital blocs. The exact social geography of these particular capital blocs was laid down through the bloody history of our long epoch. In Capital, Marx methodologically distinguished between “capital in general” and the operation of “many capitals”, analyzed in Volume I and III respectively (though one implicitly containing the other from the beginning), the former a logical structure and the latter taking a concrete appearance more sensitive to history. But this is no relation of accident, with the essence towering above, the weight of ontology behind it, and the appearance flitting across the surface, a mere virtuality. Capital as an abstract logic works itself out through the activities of its constituents, the “universal drawing itself out of a wealth of particularity,” as Jairus Banaji put it. Capital in general develops, clashing against itself, as the froth of many capitals.

The centripetal force here is competition. Capitalism is a society without guarantees. As with the interchangeable exchanges of a commodity-producing society, all positions are, strictly speaking, precarious relative to the individual. These different layers of mediation imply within them a whole grid of conflicts, as particular capitalists compete to better exploit fractions of the working class and workers externalized from reproduction compete with each other in the market in order to be exploited, resulting in a violent fragmentation that obfuscates the relations of production, substituting instead diverse outward manifestations as members of the bourgeoisie compete to install themselves behind the character-masks of different capitals. This struggle to realize a contradictory totality, capital in general, leads to a succession of ill-fitting masks. “The fact that the movement of society is full of contradictions impresses itself most strikingly on the practical bourgeois in the changes of the periodic cycle through which modern industry passes, the summit of which is the general crisis”. The destabilizing onslaught of crisis forces this contradictory totality to the extremes of its formal coherence. The antagonistic relations of social reproduction are revealed here in an abstract social totality often assumed universal amongst the classes, while the concrete particularity of need violently asserts itself, inflamed by the way the crisis intensifies the disparities in their relative degrees of externalization from reproduction. Conflict first appears over this asymmetrical distribution amongst class fractions, but often reveals its roots to be found deeper, in the fundamental relations of production, whose forces ultimately determine this reproduction.

Though the class structure may be submerged under this fragmentary appearance, these social relations appearing as fetishized fragments themselves constitute the actuality of capitalist society. Class position is never separate from the spontaneous and cultivated ideologies that crisscross social existence. Though embedded in the general cognition of its subjects, which always exists in excess of social formations, ideology follows closely behind the material recomposition of individuals out of self-consciousness of their class, dependent on all manner of “exterior” relationships ranging from the spurious to the deeply felt, into an infinite variety of social interest groups. Such mediations can be very intensive, dissolving wayward subjects within powerful structures of feeling, and able to appear as authentic products of one’s individual will. This is entailed by the specific fetish-structure of the capitalist social form, in which everyone is classified individually as commodity-sellers, merely distinguishable quantitatively. All are equal under bourgeois right, in a liberal harmony free from the materiality of systematic exploitation. In this sense, ideology emerges “spontaneously” from the social relations of capital. But fragmented identifications can also be cultivated, drawn out through deliberate attempts at “non-class composition”, in which ideological formations push people towards the liberal-democratic imperative to gain representation within the body politic (or attempt to commandeer it, as the case may be). Politics dominates class in capitalist society, displacing it in the appearance of an endlessly speciated but classless citizenry, as they variously campaign, petition, assemble, protest, advertise, analyze, persuade and sell to each other ad nauseum like carnival barkers.

The proliferation of ideological incoherence that we see in this moment, and its intensification over the turbulence of the preceding decades, reveals the extent of the crisis of bourgeois society today. The social logic of capital must be imposed and perpetuated within concrete circumstances, and so, while the circuit of capital accumulation can be grasped in abstraction from human particularity, its practical existence depends crucially on such situated, “extra-economic” ideological arrangements to tamp down class struggle, extract submission to hegemony, discipline capitalists who disrupt the balance, or keep people going to work when material compulsion is not enough. It must also gravitate towards the production of particular commodities, using particular technologies for particular markets. Capital would be content to produce qualityless widgets at ever-increasing scale indefinitely, but it is consigned to always stand in some bare relation to the social reproduction of those who bear its character-masks. We can refer to this kind of historicized picture of the social environment conducive to capital accumulation as a conjuncture, a joining together of incidental human concerns in a subordinate and form-determined manner, based upon the prevailing balance of class forces.

Though the exhaustion of economic growth is systemic and global, it is not necessarily the case that the potential depression we face will constitute an existential crisis for the capitalist system. Indeed, economic crashes tend to facilitate capitalism’s longevity through the concentration and rationalization of the surviving capitals. The global proletariat is too dispersed and disorganized to mount a significant enough challenge when the decisive moments will call for it. But in order to successfully reorganize and perpetuate capitalist social relations for another business cycle, the entire ensemble of political, ideological, and proprietary relations might have to undergo seismic adjustments before resettling into a stable regime of accumulation. Masks will fall away. Class contradictions will become unbearable, straining, and tensing to breaking points. Even if not quite an existential crisis, we may be in the midst of a conjunctural crisis, a disruption that brings these relations within the contradictory totality into sharper relief through the struggle between classes, an explosive struggle of content within form.

In the following sections, we will elaborate some of the causes and consequences of the conjunctural crisis that is developing. In the section below, we will attempt to provide a basic etiology of several of the morbid symptoms that are starting to present themselves. We will set the current stimulus bills and monetary measures in the context of the chronic overleveraging of the credit system that has accompanied the global slump in production. It becomes clear that such maneuvers are first and foremost attempts to preserve the existing complex of asset titles and price levels in order to maintain the volume of financial claims on surplus value produced around the world that are at the core of contemporary imperialism, and only as a secondary matter provide scant relief for masses of workers at the hard edges of unemployment or infection risk. In section three, we examine the recent collapse of employment, widely posited as a temporary predicament but likely to leave long-term scars on the labor market, against the wider global patterns of underemployment and the consequences this has had for the social reproduction of the proletariat. In the final section, we will look at some of the political conflicts and class struggles that have exploded as a result of the pandemic crisis. Certain terrains of struggle are expanding, while others are closing, possibly pointing to the shape of class compositions to come. The fascistic ideological passions, particularly conspiracism, which have been enervating the right since 2008 are coalescing into organization and action in the service of big capital, while the tensions of the present begin to erupt as well in a new cycle of riots over police executions, exposing the sharp contradiction between our economic dependence on business as usual and the bodily vulnerabilities of we who bear it. These are just preliminary outbreaks, but they are worth tracing, as the abyss looming over future capital accumulation will continue to intensify such conflicts.

The prefiguration of even modest utopias then offers us nothing but a disengagement from examining the particular tendencies that overdetermine the present. Any move to preserve the stability of the present totality forestalls the possibility of its abolition. Likewise, the means of achieving this cannot be prefigured but must be derived from a concrete analysis of a concrete situation. The crisis maneuvers undertaken to date appear both unimaginable without such devastation, and yet also the bare minimum tolerable to assure that demands will not exceed the capacity of bourgeois will. We have yet to see the full scope of the developing economic crisis of capital, its exact depths and contours are still in indeterminate flux. Taking shape amidst this crisis-in-formation are political subjectivities emerging in the struggles born out of necessity. The renewed importance of political expressions reveals that history is not content to allow itself to appear as the indefinite neutral passage of time. It is this subjective, conscious action upon the objective, material factors of the present that determine if we will, in fact, be living through history. More than anything else, bourgeois society fears history.

Necrosis

“Capitalist production constantly strives to overcome these immanent barriers, but it overcomes them only by means that set up the barriers afresh and on a more powerful scale.” – Marx 1981, Capital Vol. III, p. 358

This eternal fear of history leads to a tendency to distort time. The long crisis we are in presents itself as an indefinite series of small disasters that occasionally escalate into catastrophe. But their pattern and distribution reveals subterranean faultlines. Every successive business cycle follows the narrow conditions of profitability, and state policy follows the path of least resistance to ensure the bare minimum of capital accumulation, a process itself increasingly disjunct and subject to violent, incomplete cycles. Cyclical invigorations of economic activity in the advent of crisis has led to an indefinite state of debt-led growth regimes, forever deferring the arrival of the present by constantly hedging the future, only ever capable of momentarily extending the cheap credit lending and borrowing conditions necessary to reestablish a sense of general equilibrium, serving to make the barriers to reproduction increasingly insurmountable with every business cycle.

The latest iteration of this crisis management, the $2+ trillion CARES Act stimulus effort and the measures of the US Federal Reserve and Treasury Department, are fated to the same eternal return. While the bill is touted for its scope, every declaration that “this will save Main Street” reads as an insincere cliche. In practice, the stimulus package is already revealing itself to be a glorified bailout, a scaling up of now routine monetary practices that have kept capital afloat since the post-2008 “recovery” and determined by the crises preceding it. The dysfunctions in the implementation of the still-growing stimulus efforts reveal that much of the targeted elements serve only to give the appearance of a state apparatus that can adequately respond to the economic strains on the broader population. In truth, it’s all about keeping open lines of cheaply available credit to forestall the evaporation of fictitious investments heretofore unable to be realized through productive investment. It is life support for the existing arrangement of capitals. The collapse of smaller business capitals and the centralization of capital in more intensely concentrated industries remains an underlying dynamic crucial to capital’s survival at present, and therefore an inevitability.

The cracks in the foundation are becoming more and more visible as the expressed goals and concrete execution of the stimulus spending diverge. The initial $350 billion allocated in funding Payroll Protection Program (PPP) for small business lending was rapidly grabbed up, prompting an additional $320 billion in congressional funding allocation (and possibly more to come), as well as new guidelines from the Small Business Administration (SBA) on who qualifies, as large chain restaurants, hedge funds, and private equity firms had all applied for and acquired loans, meeting with public outrage. The new rule, however, does not prevent private equity-owned firms from applying for relief as long as applicants certify that “current economic uncertainty makes this loan request necessary.” As of April 20, 45% of the initial $350 billion went to larger companies who were borrowing more than $1 million, while merely 17% went to those applying for loans of less than $150,000. On a volume basis, those small businesses accounted for 74 per cent of the funds’ recipients. Following the racial composition of prior proletarianization in the US, black-owned businesses have suffered a disproportionately faster rate of closures and less aid. After public outrage, of the 234 public firms that received PPP loan funding, only 14 had promised to return the money.

The $50 billion Payroll Support Program for airlines has also proven itself a simple matter to circumvent, as United Airlines received $5 billion from the US Treasury to retain staff, but is still cutting the hours of 15,000 workers. Despite the 120-day ban on evictions of tenants that reside in properties that receive federal subsidies or have federally-backed mortgages, these landlords are still executing evictions, and tenants in the rental market at large are left to a patchwork of state and municipal level measures of varying efficacy, themselves subject to even less capacity for enforcement. The only saving grace in many municipalities is that the courts have been closed, stalling what will become a wave of eviction filings. The temporary expansion of unemployment insurance benefits will likely never get to the mass of unemployed, as governors are cutting off new unemployment benefits before many applicants have even received their first checks, following the stresses to reopen their economies from the federal government, protests, and budgetary strains from the loss of sales tax revenue. Stimulus checks being sent to dead people offer an almost too poetic reflection of reality in this naked redistribution of social wealth to capital. Whatever might have remained of America’s mythic Main Street before this, it is surely now nothing more than an empty shell, upon which political parties will still hang their banners in the months to come.

Even as we watch stimulus efforts turn into a life support system for capital, turning our attention to the scale of response on the part of the US Treasury Department and Federal Reserve should relieve us of the illusion that they could be anything but. While central bank intervention and the stop-gap measures of governments have taken center-stage in the whirlwind timeline of the pandemic’s economic fallout, it must be remembered that these direct measures of intervention returned months before the pandemic. In September 2019, the unexpected spike in overnight money market rates led to a liquidity crisis in the repurchase agreement (repo) market, prompting swift intervention by the US Federal Reserve. The immediate trigger for this was the quarterly corporate tax payment deadline on September 16 leading to a high volume of withdrawals from bank and money market mutual fund accounts into the US Treasury’s account at the Federal Reserve, leaving bank reserves $120 billion light and unable to match the volume of repo market agreements in Treasury securities that required financing the next day. The resulting inflexibility in banks to increase lending from their thinning margin of excess reserves, in part due to reserve requirements imposed after the 2008 financial crisis, led to more loan requests from US financial institutions to the federal funds market, as banks resorted to Federal Home Loan Banks over interbank lending, leading to a decreased supply in federal funds lending and an excess demand among banks and financial institutions. Initial Fed intervention in September offered up to $53 billion in additional reserves and led to a decline in interest rates for lending, and the effective federal funds rate was lowered to stay within a stable target range. By mid-October, it appeared that this would not be enough to address the extent of the liquidity problem, as trade disputes signaled the possibility that the securitized loans at the base of this liquidity market might become non-performing, and the Federal Reserve announced it would be engaging in overnight repo operations of up to $60 billion a month. Over the course of 2019, the Fed cut the interest rate 3 times, almost down to zero, to stabilize reserves for lending in money markets, with plans to reassess in January 2020.

But the hopes for a resurgence of economic vitality were dashed by the beginning of the year, though these emergency actions themselves, implemented to counteract a turbulent environment for liquidity operations, should already have been a massive clue that this would be the case. In the bailout effort from the 2008 crisis, the quantitative easing operations undertaken by the Treasury and Federal Reserve, to keep markets solvent and credit available for lending through asset purchases, saw the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet expand by $4.5 trillion from 2010 to 2015. Furthermore, it cannot be forgotten that much of the global economy after the 2008 crisis was further bolstered by China’s debt stimulus fueled infrastructure projects, running a debt-fueled growth regime of roughly $586 billion USD. It was only by 2018 that the Federal Reserve began attempts to deleverage, though the gradual offloading of $800 billion in assets was met by stock market volatility and by September 2019 immediately met with this liquidity crisis set off in the repo markets.

By early 2020, the emerging disturbances in Wuhan, the manufacturing metropole in the Hubei province of China, started roiling supply chains and put many key industries in danger of financial insolvency, thwarting the Federal Reserve’s expectations of rolling back its efforts and prompting escalated intervention in money markets and repo operations. The months of February, March, and April 2020 saw an unprecedented scale of operations, an expansion of the Fed’s repo market operations and a reintroduction of quantitative easing up to hundreds of billions of dollars in a whirlwind series of overnight decisions as global stock markets plunged. From February 24th to April 27th, the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet by $2.6 trillion to a total of roughly $7.1 trillion. These trends, having already been in motion, should sufficiently deflate any notions that the so-called fundamentals of the distant bourgeois god known as “the economy” were at all strong even months before the pandemic. The circulation of money capital itself appears incapable of operating without a ventilator.

Now, as part of stimulus efforts undertaken to avoid a depression at all costs, the Federal Reserve enters into new territory, the consequences of which remain to be seen. The precedent set by the government bond purchases that characterized the Federal Reserve’s post-2008 quantitative easing policy has left little terrain of movement than what is currently underway: the introduction of a wide variety of programs and lending facilities to directly purchase assets, now notably including corporate debt, via direct lending, buying bonds, and buying loans. What has rightly prompted even more concern about the possible outcomes of this hail mary is the Fed’s purchases of high-risk, high-yield corporate debt, known as junk-rated bonds, which could put what is effectively the world’s central bank towards a point of no return. This is all occurring with the facilitation of $2.3 trillion in credit lines opened through the newly fashioned lending facilities, and interest rates set almost at zero with speculations of going negative. In addition to the $3 trillion added to Fed capacity for liquidity support in the current quarter, largely from the stimulus efforts, the US Treasury expects to borrow a further $677 billion in the three months before September. Having already borrowed $477 billion in the first quarter of the year, it would bring the total amount to more than $4 trillion for the full fiscal year. As if the thin veil covering the obvious bailout underway was not enough, all pretense is stripped as a division of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, has been hired by the Federal Reserve to act as the investment manager for three of the newly created lending facilities: two Fed-backed vehicles that will buy corporate bonds, and a program that will buy mortgage-backed securities issued by US government agencies. Furthermore, BlackRock can direct the Federal Reserve to purchase their own assets, including their own junk-rated exchange-trade fund (ETF) bonds, and BlackRock employees involved in this effort can use the knowledge they gained as advisors for trading purposes that benefit their own firm after a mere 2-week “cooling-off” period.

Lest we make the mistake of thinking the Fed has merely gone rogue, let’s briefly consider the doctrine of negative interest rates recently implemented in the turbulent economies of other capitalist powers. Setting central bank deposit rates negative effectively charges a fee for storing money-capital, forcing banking institutions to dump their holdings into whatever asset markets seem remotely viable, thus “growing” the economy. Even before the US repo market liquidity crisis of September 2019, the European Central Bank (ECB) had dropped the deposit rate to -0.5%, the lowest on record, and initiated a new quantitative easing program of €20 billion per month in asset purchases, for the third time in a decade. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) followed suit, cutting rates in multiple rounds. The ECB and BOJ had both experimented with negative interest rates previously: the ECB in 2014 to shake off the slump from the 2011 sovereign debt crisis and at a time when the unemployment rate in the eurozone was ~12%; Japan in 2016 in a desperate bid to combat deflation. Though neither case worked as intended in the first iteration, each central bank sought this time to go even more negative to inject some activity into undeniably sagging growth. That the largest currency zones in the world all engaged in periodic and escalating programs of severe interest rate cuts and massive asset buyouts throughout the 2010s, and with little success, suggests not so much an extremist interpretation of mandate on the part of central banks, as some post-Keynesians accuse, but rather an expression of structural decrepitude.

A cursory overview of Federal Reserve policy over the past few decades reveals that these new drastic measures actually reflect the limited range of motion available to mitigate crisis while still maintaining the reproduction of capitalist relations. The Volcker shock of 1979, in the unprecedented raising of interest rates with the intention of curbing inflation, set off a wave of unemployment in the US and cemented the finance-dominated global restructuring of industry that was progressively taking shape throughout the 1970s, ultimately meeting its own fate once again in the 1987 crash of the high-risk, high-yield junk bond market that fuelled the financial means of this global expansion. The ensuing neoliberal regime of accumulation from 1982-1997 unleashed growth in the expansion of industrial capital further into the Global South and peripheries, bolstering rates of profit, but nowhere near the highs prior to the downturn of the 1970s. Following the 1987 junk bond crash, the Federal Reserve of the 1990s, under the tenure of Alan Greenspan, saw the official onset of such practices dubbed by Robert Brenner as “asset price Keynesianiam,” cementing as official policy market capitalizations of publicly traded companies through direct liquidity support via lowering the Federal Funds Rate. This effectively freed up credit to stimulate asset price inflation, and with it an illusory “wealth effect” in which personal fortunes and GDP alike depended on low-interest rates. The rise in pension funds and the doctrine of shareholder value, now with official backing in Federal Reserve policy, left the US economy perpetually subject to and ultimately dependent on the inflation of asset bubbles. This culminated first in the chain of events set off by the East Asian crisis of 1997, itself the cumulative effect of the Japanese banking crisis of the 1980s that would domino into a real estate bubble in Thailand by the early 1990s, resulting in a series of chain reactions throughout the region that spilled over into the Western economies through the collapse of the Long-Term Capital Management Hedge Fund in 1998 and the dotcom bubble crash of 2000. Asset price valuations have long been the driving force of the projection of vitality for capital, not the expansion of production, which has long been redundant and overproducing due to a high organic composition of capital. The terrain of expansion is increasingly insufficient relative to the mass of capital valuations it requires. Expansion must take the shape of an upward ticker in stock market activity. Anything else would be effective suicide. The 2008 housing bubble that ripped through the credit-reliant construction and real estate industries prompted the Federal Reserve to respond with both lowering rates and direct asset purchases in quantitative easing.

While private capital requires a relatively autonomous state to assist in guaranteeing reproduction, these roles have increasingly become intermeshed, forming neither a state takeover of the free market, as bemoaned by devotees of the invisible hand, nor the gutting of the state, as often decried by left critics of “neoliberalism”. What we see is rather a reflection of the growing centralization of capital and its concentration within specific spheres of industry, in this case, the banking and finance sector involved in controlling circulatory flows of money-capital, drawing the international state system into a more coordinated global regime of accumulation that cannot cohere due to global overaccumulation of capital. The instance of BlackRock’s direct involvement in directing Federal Reserve corporate debt purchases reveals that the world’s most powerful central banking institution’s status as “lender of last resort” has been resorted to so frequently in recent history that it has effectively displaced the executive as the central “committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” Financial accumulation to this degree has meant that global manufacturing overcapacity and declining output can only be continually managed by an ever more swelling and carefully attenuated market regime, a regime where accumulation primarily occurs through the cornering of market shares through appropriations of the flows of realizable surplus value via property-based mechanisms of capital acquisitions that consolidate firms. We see here the rise of multinational conglomerates with massive asset portfolios that allow them to dominate the labor of large swaths of the global working class in both direct and indirect ways. Due to the decline in complete accumulation by means of reproductive expansion, credit becomes increasingly important to maintaining the continuity of economic functions, and thus the appearance of capital writ large as profit-making via price speculations and fictitious profit generation.

Now that the future is arriving, decades of political imperatives to buttress risk at all costs in order to maintain dominance has left too many landmines. The federal government’s insurance of risky corporate debt poses a new problem, of which the outcome is still unknown. The IMF raised the alarm over a $19 trillion corporate debt “time bomb” in its Global Financial Stability Report in October of 2019. Tobias Adrian and Fabio Natalucci, two senior IMF officials, said of their findings, “We look at the potential impact of a material economic slowdown [that would trigger said “time bomb”] – [requiring only] one that is half as severe as the global financial crisis of 2007-08. Our conclusion is sobering: debt owed by firms unable to cover interest expenses with earnings, which we call corporate debt at risk, could rise to $19 trillion. That is almost 40% of total corporate debt in the economies we studied.” To place this alarming conclusion in the present context, the impact of the present crisis in the lockdown periods results in a global average rate of GDP growth of -3.0%, as estimated by the IMF. For further context, the impact of the Global Financial Crisis of 2009 was -0.1%. Two trillion dollars of corporate debt is set to be rolled over this year, and according to findings from the OECD, more than half of all outstanding investment-grade corporate bonds have a BBB credit rating, just one grade above junk status. If we want to understand why such intensive measures are being taken by central banks at the present moment to keep credit lines open and available, there it is. To date, US companies have continued to take on debt, borrowing a year’s worth of cash in the past 5 months alone. Here we find something of the double edged sword of liquidity. Everything may be done to maintain the circulation of money-capital in hopes of realizing a prospective value, but circulation itself yields nothing. Merely adding to the money supply might throw things into a sense of motion, but it may still do so with no traction. Now, as the threat of hyperinflation looms, Goldman Sachs has begun establishing short positions on the US dollar, anticipating the currency’s devaluation and preparing to make a profit on it. For all that is made of the Federal Reserve and its role, it is clearly only buckling under the pressure of what is required to maintain capital at present, and that is cheap credit and viable conditions for lending by any means necessary.

Amputation

“The greater the social wealth, the functioning capital, the extent and energy of its growth, and, therefore, also the absolute mass of the proletariat and the productivity of its labour, the greater is the industrial reserve army. The same causes which develop the expansive power of capital, also develop the labour power at its disposal. The relative mass of the industrial reserve army thus increases with the potential energy of wealth. But the greater this reserve army in proportion to the active labour army, the greater is the mass of a consolidated surplus population, whose misery is in inverse ratio to the amount of torture it has to undergo in the form of labour. The more extensive, finally, the pauperized sections of the working class and the industrial reserve army, the greater is official pauperism. This is the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.” – Marx 1976, Capital Vol. I, p. 798

Meanwhile, unemployment has skyrocketed with no end in sight, stimulated by the shelter in place orders instituted around the country. The official count of unemployment insurance filings are, as of the time of publication, roughly 40.8 million since mid-March, adding to the existing 7.1 million already on UI, with the US real unemployment rate in April reaching a post-WWII high of 14.7%. The measurement that month for the U6 rate, which includes workers precariously employed and involuntarily part-time for economic reasons and is by definition higher than “real unemployment,” was at 22.8%. Given that data collection for the most recent surveys are affected by the pandemic, these figures are underestimations of the actual number of people suffering significant cuts to their income. At the beginning of June, the financial press and the state’s economic advisors touted a success in an apparent employment resurgence, as 2.5 million jobs were “created” and the unemployment rate fell to 13.3%. U6 only dropped down to 21.2%. While temporary lay-offs declined from 18.1 million to 15.3 million in May, the number of permanent job losses increased from 2 million to 2.3 million. Furthermore, the US Labor Department already conceded making errors in the employment classifications of the May report, including counting 4.9 million temporarily laid-off people as employed, revealing that any “impressive” numbers are in fact quite deceptive.

It appears quite clear that this, rather than a resilient economy arising like a phoenix from the ashes of its immolation, is more likely a reflection of just how weak efforts to reopen have been thus far. While leisure and hospitality services appear to be hailed as a sector surging back to work, the unemployment rate for this sector is still at 35.9%. Government unemployment is also continuing to surge, as 1.6 million were unemployed in this sector the last two months alone, following the contours of austerity we can expect in any attempts at “recovery.” We still have yet to see the full effects on long-term unemployment that the threats of a second wave of COVID-19 infections may have, and further what will happen to economic activity once additional funding for unemployment relief halts in July, should a stimulus effort here not be repeated. It is now still estimated that at least 42% of recent layoffs will result in permanent job loss. In the US, it is also clear that this wave of unemployment is cutting along prior racializations of labor precarity, with hispanic and black workers facing disproportionately higher rates of unemployment than white workers. Globally, the International Labor Organization estimates that 1.25 billion workers, 40% of the total global workforce, are employed in sectors vulnerable to cuts in hours due to expected declines in output. Counted in lost hours, we can expect the equivalent of 305 million full-time jobs to disappear, constituting 10.5% of the worldwide total work hours in the last pre-crisis quarter, suggesting underemployment will far outstrip the unemployment numbers alone. In the vast informal sector in which 60% of workers eke out a living, there was a 60% decline in earnings in the first month of lockdowns, and as high as 81% in Africa and Latin America. Since a missed day’s work means missed income full stop, informal workers will, in the words of the ILO, “face this dilemma: die from hunger or die from the virus.”

At the end of their recent report linked above, the ILO advocates strong “labor market institutions” and “well-resourced social protection systems” to ensure a “job-rich recovery.” This comes off as idealistic and naive when set against the context of the global slump of the last few decades, in which the fundamental reproductive institution for proletarians, wage labor, has increasingly given way to the uncertainties and tribulations of wageless life. The growth of informality itself is a consequence of the rising organic composition of capital, a tendency where the double bind at the core of the capitalist value-form – between socially necessary labor-time, the first determinant of the value that can be realized on the market given prevailing technical and social conditions of production, and surplus labor, which marks the proportion of this value which can be appropriated by the capitalist above the costs of production – ratchets production in the direction of secular, systemic and often “premature” deindustrialization, permanently expelling millions of workers from manufacturing in several rounds of restructuring since the end of the post-war boom. There is a persistent decline in labor demand and in labor share of income, as the capitalist class reorganizes the labor process, suppresses wage growth, and opens barriers to capital, yoking workers of the world into a single giant labor market exploited as nodes in logistics chains increasingly stationed in exurban peripheries, still dependent upon the social wage fund, but perpetually underemployed. The “working class” strives daily to survive but less and less of this work itself is integrated into the circuit of valorization of capital.

The incapacity of the global economy to adequately generate jobs is evidenced in the travails of youth unemployment. As new entrants into the labor market, young workers are subject to whatever potential economic growth may or may not contain for the reproduction of the working class intergenerationally and as such give us a glimpse of future trends. In the months before the pandemic, youth unemployment (ages 15-24) was at 13% globally, and up to ~40% in the Middle East and North Africa, a steady rise from 2008. In addition to the more temporary unemployment rates, youth labor force participation is at an all-time low, with 21% of young people fully disengaged from the economy or education. Of those working, 80% of young workers around the world are in informal work, as opposed to 60% of older adults. And young workers have to travel farther to find the work they do have: 70% of labor migrants are under the age of 30. There are several reasons for this dismal state of affairs. First, there is an increase in early school dropouts, due to precarity at home and the need for children to labor, usually either to take over housework for an older caretaker who is out earning money or to join the informal workforce themselves, often permanently barring them from ever obtaining stable, formal employment. Simultaneously, there are diminishing returns on higher education, with longer transition times between school and work, and for consistently less compensation relative to costs and time spent in education, with these transition times increasingly uncorrelated with education level, instead reflecting job availability. This latter fact can perhaps be accounted for by the overall trajectory of work composition, with semi-skilled jobs evaporating in favor so-called low-skilled (that is, low-paid) work. Entry-level jobs are becoming less compensatory on average, and often lead only to a quagmire of dead-end work – nearly 40% of youth fail to transition to stable jobs even when they are older, a phenomenon referred to as “scarring” by the ILO to describe how failed labor market integration in youth follows workers around for many years into their adulthood.

The rhetoric of scarring suggests a kind of stigma that marks each worker as they travel through life, euphemizing and obscuring what is actually a structural inability of developing economies to adequately absorb new workers. This is especially egregious when considering that job prospects are so stagnant compared to population growth that the global economy will need to generate 5 million new jobs each month just to keep unemployment rates constant, a veritable pipe dream now. Finally, young workers are especially vulnerable to long term scarring from the pandemic crisis. They are generally more sensitive to recessions, experiencing steeper inclines in the unemployment rate as they are laid off before older coworkers. In addition to the aforementioned overrepresentation in informal work, young workers are more likely to have precarious job arrangements, such as gig work, and make up the primary workforce for the retail, hospitality, and food service industries that are most affected by the lockdowns. Jobs among youth are composed of automatable tasks at a higher rate, leaving them uniquely susceptible to automation-based job loss, both historically and in the future as companies seize the vacuum left by the pandemic to rationalize their production costs. The very ability of capitalism to sustain the bare reproduction of the proletariat within the exigencies of accumulation is receding over the horizon.

This dialectical process of subsuming creative labor-power, replacing it wherever possible with machinic repetition of motion and cutting the human being loose (so fundamental that Marx referred to it as the general law of capitalist accumulation) is exacerbated by a parallel bloodbath in which masses are newly proletarianized in droves. Between 1980 and 2000, the global workforce doubled in size, before adding a further 1.3 billion workers by 2019. These increases came from the absorption of workers following the full integration into global capital of the USSR and China (who were not previously counted), but significant segments came from a wave of land grabs, from agribusiness and extractive industries, and debt traps, where subsistence peasants forced into the market take out loans and microfinance to counteract losses from intensified global competition, effectively abolishing the smallholding peasantry as a significant class, pushing them to the margins of the market in labor-power as new proletarians. That capital is little prepared or interested in incorporating the swollen ranks of the reserve army of labor is evidenced in the massive growth of exurban slums and crowded megacities, with hinterlands many hours from the new factories. Any given person may cycle through a job relevant to the production of value for a time, but each individual, especially in the age of longer, more treacherous and more frequent migrations, is strictly expendable. The condition of dependence on the labor market for bare subsistence is generalized, but the labor market is everywhere shedding labor to cut costs.

These are the material circumstances that overdetermine possible economic recoveries from recessions, which have been increasingly jobless, with the restoration of employment levels to pre-recession rates taking longer in each of the last five recessions, lagging behind other indicators. Returning to the US, the Great Recession took a full ten years to recover in this sense, and even this has been uneven, with unemployment rates officially higher than before 2007 in more than 90% of metro areas. But more significant than the literal number of jobs is the stagnant wage level, which was flat between 2002 and 2014, only recently producing modest gains. Labor force participation has declined absolutely from ~66% in 2008 to ~63% in 2019, causing long term unemployment to creep up as a proportion of total unemployment. At least 1.5 million adults had effectively dropped out of the workforce, and therefore unemployment rate statistics, by 2017. There were also significant shufflings, as jobs permanently shifted from some sectors to others. New jobs tended to be paid less, receive less benefits, have less long-term prospects and schedule less hours. Ninety-five percent of jobs created since 2005 have been independent contracting, temporary, part-time or on-call. Indeed, some of the most visible and celebrated innovations of the new “recovery economy” were gig platform-middlemen like Uber, lauded for “disrupting” and redefining work itself. The average tenure at these shit jobs has dropped to 4.4 years, and the rates of switching jobs, endlessly churning over in the vain search for better pay, hopped to record highs amongst the growing proportion of low-wage workers as of 2019. In short, the capacity of the economy to support wage growth in proportion to productivity growth, to proffer the expected quality of life from the postwar boom that both left and right nationalists nostalgically yearn for, is severely truncated as the dynamics of accumulation place hard limits on profitable exploitation. Meanwhile the remaining “decent” jobs are left to get cyclically hollowed out as the political consensus has converged on a program of constantly escalating the gutting process.

Against these dwindling fortunes, the severe contraction in income seen in the last two months will rip holes in the tattered safety net of private household finance. Earlier this year, the Fed found that 39% of Americans could not cover an unexpected $400 expense without going into debt, if at all. Ten percent already could not cover existing bills. This is a small wonder when 58% have less than $1000 in savings at any one time. Many have become dependent on side hustles to make ends meet. Meanwhile, the costs of living have gone up. Transportation costs have grown 54% as average commute times have lengthened, which can be correlated with housing prices, now accounting for 9.2% of total household expenditures. Food expenses as share of income have remained steady at 10%, except for the lowest quintile of households, where it has grown to 35%.

After $19.2 trillion in household wealth completely evaporated with the 2008 mortgage and subsequent retirement savings crisis, homeownership, long a mainstay in the US middle-class reaction formation, has increasingly given way to renting, with the renter population growing 10% between 2001 and 2015, primarily among older people. Median rent has gone up 32% over the same time period, as median income has fallen 0.1%. Thirty-eight percent of renters are rent-burdened, forking over at least 30% of their monthly income to their landlords, and 17% severely so, paying over 50% of their income. Of this severely rent-burdened population, the Pew Research Center found that over half had less than $10 in liquid assets in 2015. This bleeding out of savings quickly began to hemorrhage with the onset of the pandemic. On April 1, just two weeks after the initial spike in unemployment, 31% of renters did not pay their landlords. This dropped down to 20% in May, mostly due to the arrival of the one-time stimulus checks. Some percentage of this constitutes a newly politicized bloc of rent strikers and tenant unions, a trend that we will return to below, but the vast majority must be understood as the disorganized fallout of the abrupt plunge into wagelessness – especially when considering that 19% already missed rent every month before the pandemic.

For homeowners, the situation is also grim. In the largest single-month gain on record, US home loan delinquencies surged by 1.6 million in April. The proportion of loans over 30 days delinquent rose to 6.45%, with 3.4 million loans delinquent and another 211,000 properties now scheduled for foreclosure. While federal relief efforts aim to address this and avoid the foreclosure wave following 2008 that is seared into the collective memory, the sum total of these efforts are a forbearance program to delay payments for a six-month period without penalty, which assumes a sharper rebound in an economic recovery than any forecast can yet foretell. As of May 12, 4.7 million borrowers are in forbearance on their loans. As for businesses, commercial mortgage backed securities (CMBS) are in a severely precarious position, as it was announced that $45 billion of loans bundled into US CMBS were overdue and entering “grace periods” in April. Of these, the Mall of America’s $1.4 billion mortgage is now delinquent, sending the threat of a ripple of contagion throughout the rest of the market. To complicate the perils of the US CMBS market and fallout effects on retail further, a whistleblower in 2019 revealed systemic efforts to inflate profits and wipe losses from the records of these loans, adjustments that served to continue CMBS lending and inflate the valuation of these sectors so that borrowers appear more creditworthy and credit can be extended. A familiar scenario. Facing risks of default exacerbated by the contraction in activity in hotels and retail, the potential fall in the wake of this bubble is all the more precipitous. This will necessarily also foreclose employment for millions more, and those home loans in forbearance may require more than six months to avoid delinquency.

This disparity is made up for with debt. Peaking in 2008, the US household debt to GDP ratio has settled around 76%, while the debt to income ratio was at 96%, as of 2017. Auto lending in particular has taken off, 20% of which are subprime loans made secure to the lender with the implementation of remotely-controlled devices that the lender can use to interrupt the car’s starter when the loan is delinquent. Severe delinquencies (90+ days without payment) have doubled for both auto and student loan debt since 2004, the latter being the fastest growing type of household debt. Credit card debt was actually decreasing over the last few years, until March of this year, when it spiked 23%, presumably as people scrambled to hold their lives together in the absence of real income. We can expect this trend to worsen.

Observing this ongoing breakdown of the wage relation’s legitimacy in guaranteeing reproduction, we can apprehend the trajectory of its deterioration through the concept of a “social wage fund.” We can define the social wage fund as the aggregate of personal wage compensation, benefits spending, and state expenditures on public infrastructure, social welfare and common resources; in short, the general costs of production in variable capital and business operations taxation that capitalists must forfeit for purposes of general social reproduction and which impinges on the rate of profit. As the rate of profit and the rate of accumulation slug downwards, there is a struggle over the value of labor-power as capitalists tighten the vice grip it holds over this fund, both at the point of origin in the diminishing payouts received by proletarians for their labor and through intensified recuperation with the privatization and commodification of everything possible. This leaves the totality of social reproduction in an increasingly fragile and vulnerable state, with more and more people being expelled from the material community of capital to attempt to survive in abjection. We have already covered the decline in real wages and wage-labor conditions at some length, but to really understand what is at stake in the downturn and subsequent intensification of class warfare we will cursorily detail the pattern of deterioration of social infrastructure, which has many manifestations too numerous to fully expand on.

We will briefly summarize the nature of the class conflicts over healthcare insurance in order to demonstrate the particular limits that healthcare imposes. There is an intrinsic relation between the declining investments of variable capital that compose the social wage fund, and the process of externalizing costs of labor’s reproduction in the capitalist subsumption of healthcare services. In the production process, the value of labor-power constitutes a diversion of the quantity of value expropriated by the capitalist, primarily in the form of reluctantly doling out wages. The value of labor-power is defined by Marx as the sum of values of the necessary goods which go into the reproduction of the worker. The ratio of this to the total value formation, as set by the socially necessary labor time of the commodity, brackets the entirety of surplus value, the increase of which is the sole aim of capital, and the necessary condition for its material reproduction. As the socially necessary labor time of commodities generally drops, the value magnitudes obtainable from the market drop as well, reflected in the volatile movement of prices outside of various special conditions. This constitutes a perennial and even existential problem for capital that underlies the tendency for the fall in the rate of profit, driving it along a winding, nonlinear path towards the breakdown of reproduction. If the value of labor-power were fixed in place, this would constitute a severe problem for capital accumulation, and indeed it did as the growth engine of postwar expansion dwindled to a low hum in the mid-1970s, crashing into the floor set by a historic height of wage levels in the imperial core that reflected the balance of class forces rising from the corporatist union-mediated labor accord. The struggle over the value of labor-power has been central to a countertendency to this crisis, through labor market arbitrage, wage suppression, and the “organic” decline of the value of labor-power, as necessary goods cheapen due to the improvements in necessary labor times mentioned above. Having once been necessitated by the Great Depression, the persistent escalation of conflict pushed by the proletariat and the resulting conjunctural crisis of the interwar period, the succeeding interregnum saw the progressive deterioration of proletarian class composition, midwifed by ruthless anti-communist containment worldwide and bureaucratic anti-militancy in the labor movement. This set the conditions for the boss’s offensive and neoliberal restructuring that enabled a minor but insufficient rally in the rate of profit between 1982 and 1997 before exhausting itself into the slump we are in today.

An apt metonym for the effect that this process has had on the extreme and preventable fatality rate of COVID-19 in the US might be the recent flash floods in Midland, MI, as two dams burst, forcing 10,000 people to evacuate and flushing a Federal superfund site near the Dow Chemical plant into the watershed. The dams are privately owned, by Boyce HydroPower, who bought the dams but refused to finance their retrofitting and maintenance, leading to their inability to withstand high water flow. Over half of the dams in the US are privately owned by energy companies, large landowners, and private equity firms in an increasingly crowded “public infrastructure market”. Reconfiguring basic infrastructure as a new revenue-generating asset class has only intensified a long pattern of systematic disinvestment, leading to pronounced physical degradation. The private companies investing in them often have their profits secured through predatory contracts with municipalities which guarantee that any losses are covered through taxes, leaving little interest in that wasteful and unproductive enterprise of routine maintenance. The incremental excision of all state expenditure on public goods, in waves of austerity forced through over a decimated workers’ movement, has affected nearly every facet of life. Similar patterns of privateering and disinvestment, with the added dynamic of ruthless rent-seeking at every access point, has left the medical system with enough cracks in it to buckle against the floodwaters of infection.

There are a number of components that make up the blanket healthcare system in the US, each subsumed by capital in their own way, contributing to an infrastructure defined by extremely patchy coverage, absurd costs and declining, uneven quality. The dilemma for capital, starkly revealed now by the willful sacrifice of thousands of lives a day, is between, one the one side, allowing for the expansion of the social wage fund that robust public health measures would require, and thus cut into the already suffering rate of profit, and, on the other, letting the general health of the populace decline to the point where it cuts into productivity. Historically, the US capitalist class has opted to thread this needle very close to the bare minimum, foisting more miseries and indignities onto the working class as increasing portions come to contribute to the economy not primarily as labor-power, but as “medical consumers.” The private healthcare industry has a unique position within the wider historical process of declining profitability and the suppression of the social wage fund.

We relate this to the long-term deterioration of the public health and healthcare system in the US, constituting a kind of class-based triage, which underlies the current difficulties it faces with COVID-19 and going some way to explaining the unique severity of the pandemic here in the US. Generally, we can characterize the trend in healthcare profiteering as one of partial subsumption which, though this situation would normally hurt the growth of an industry, has been circumnavigated with the ability to exploit the inelastic demand of a captive market, due to healthcare’s place as a central pillar of necessary social reproduction. Marx used the example of the architect to explain how our cognitive capacities enable us to change our environment, and therefore our own natures, but a more fitting example might be the physician, fundamentally transforming the ways we inhabit our bodies.

Capital progressively subsumes social life into relation with it. Social reproduction as a real category, that is, as a series of concrete activities oriented towards the maintenance of populations, is itself a consequence of this process of subsumption, as capital institutes a rigorous separation between work and life activities. The inclusion of public health and healthcare within social reproduction means that it is organized out of the social wage fund, and represents a cost within the value of labor-power. It is unsurprising then that the first battles over the funding source and method of distribution emerged as dependence on the wage became generalized at the turn of the century with the rise of US industrial prominence. Struggles over the definition and administration of public health measures emerged directly out of the work of reformist leagues attempting to sanitize urban slums and agitation on the part of workers to improve their working conditions in the first decades of the 20th century. The hazards of life for industrial workers lead to the development of a hodge-podge of illness, accident and death insurance plans, originally created to overcome the chronic unemployment that would leave them wageless to fend for themselves. Such plans were often perpetually low on funds, with premiums still too high for many workers, in part from strict price controls for drugs, hospital care and medical services maintained by reactionary professional lobbies that functioned as cartels at the time, such as the American Medical Association and American Hospital Association.

More important than these plans were the union-sponsored clinics, attempts by workers to directly organize medical services in conjunction with medical professionals, some of which still exist. The first insurance benefits offered by employers were specifically to attack these meager but autonomous worker organizations while undermining unions generally, a reaction to the balance of class forces shifting in the direction of labor that had been building with the union movement. The 1930s saw the widespread adoption of the hospital model of distributing care, as they became attractive “cost centers,” stimulating the parallel growth of the private voluntary insurance industry. As the network of independent worker clinics was displaced by the hospital system, the battle lines moved and workers began to fight for insurance plans and other forms of payment support rather than for direct control over the care itself. In other words, they increasingly had to accept the terms of commodification. But the inadequacy of union insurance plans and the conditional nature of employer plans, based on the principle of “cost-sharing,” lead to agitation for publicly funded coverage. The American Federation of Labor of Samuel Gompers, its latent conservatism coming to the fore as the wave of interwar class struggles began to crest in the early 1930s, opposed universal coverage on the grounds that it would counteract the unions’ appeal, as it would cover union members and nonmembers alike.

Within this struggle, workers attempted to connect public health with working conditions, pointing to occupational hazards, chronic conditions and illnesses plaguing the industrial labor force by exerting influence primarily through control over the shop floor. As the Depression plunged millions into poverty, there was a rash of lawsuits over workplace injury and disease seeking remuneration from employers. The climate of ascendant labor struggles pushed the courts in a direction more sympathetic to labor and the framework for worker’s compensation policies began to emerge from this era of case law. But as shop-floor control was wrested away with the move from militancy towards normalized business relations, worker’s compensation became the official solution to dangerous and harmful work environments, not autonomy in the workplace enabling improved conditions. The labor movement, having initiated the first organizations of mass healthcare and public health, was outmaneuvered and had forfeited its conflictual and definitive place within the management of social reproduction for a position firmly outside of it, consigned to negotiating for access from across the counter. In the midst of these battles, both unions, with massively expanded memberships beyond the administrative capacities of the old clinics, and the bosses, eager for cheap concessions that would not give in to unions and lessen their domination, increasingly began to turn towards private, third-party insurance schemes.

With the Federal government guaranteeing industrial profits with the “cost plus” financing plans during WWII, more companies bought plans for their employees. This generalized in the post-war period, with coverage for unionized workers expanding from 625,000 beneficiaries to 30 million between 1945 and 1954. This new paradigm gave ample room for expansion. Hospitals, traditionally treated as community utilities, were becoming high-tech complexes with large staffs and overheads. Nurses and other hospital workers began to unionize themselves, driving their wages up. Hospital services went up in cost, which insurance companies made no attempts to negotiate back down, preferring to raise premiums. Meanwhile, though union involvement in medicine had its origins in coverage for the unemployed, healthcare access had become a matter conditional on employment and union representation. The social forces were growing for another push at universal healthcare, as reformist organizations joined with unions to mobilize the uninsured. They struggled to manage benefits for retiring members, particularly the elderly, culminating in the creation of Medicare and Medicaid. These proved to be the high watermark, incomplete as they are, in the aborted project of constructing a national health insurance. These programs became frequent targets for irate conservatives or slick neoliberals looking for governmental bloat to trim in times of austerity, as the program funds were increasingly eyed as a revenue source for insurance companies.