Doug Enaa Greene on the Hungarian Soviet Republic and its tragic defeat.

It is 1919 and Russia is in the midst of a ruthless civil war with fronts stretching for thousands of kilometers across a ruined country. On one side are aristocrats and capitalists who had been overthrown less than two years before and are now desperately fighting to return to power. On the other side are the workers and peasants of the former Russian Empire, who had seized power from their former masters and were now determined to defend it. It is a savage struggle between two irreconcilable worlds with only two ways it can end: total victory or death.

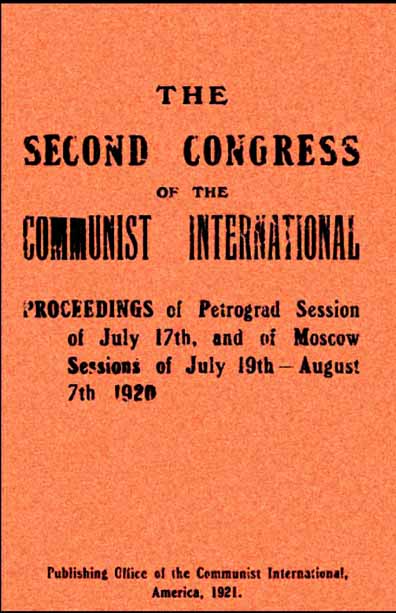

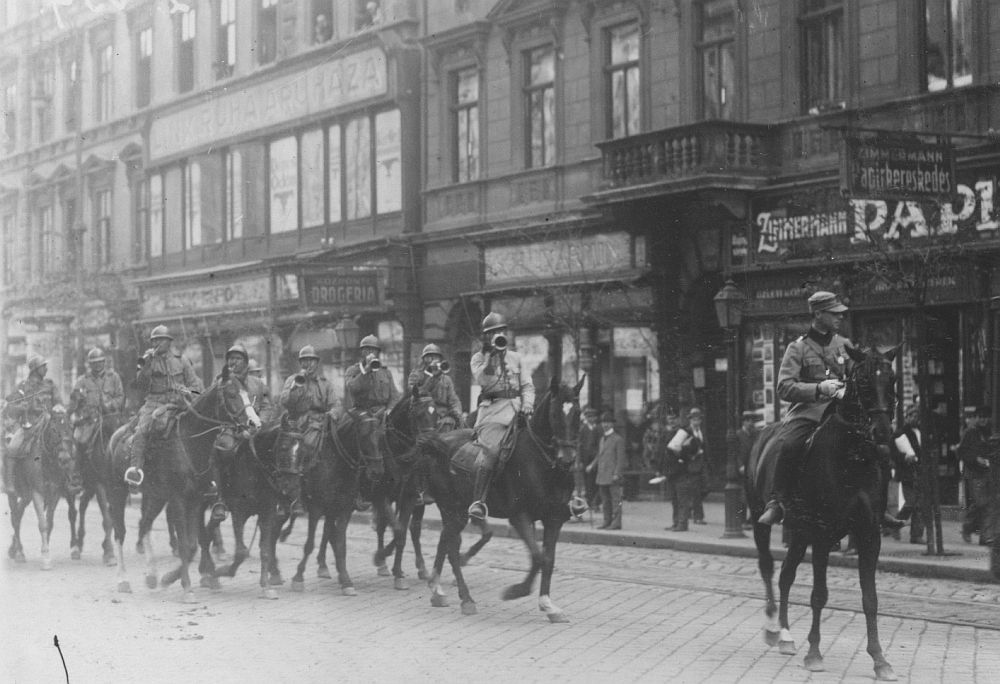

The Bolsheviks did not see their struggle as merely the concern of Russians but as the spark of a world revolution against exploitation and oppression. During the early months of 1919, the Bolshevik spark appeared to set fire to the old order of Europe. Revolution and revolt gripped Germany, Austria, Spain, Scotland, Ireland, and Italy. Other countries seemed poised for upheaval. Understanding the importance of these events, Commissar of War Leon Trotsky explained to soldiers of the Red Army:

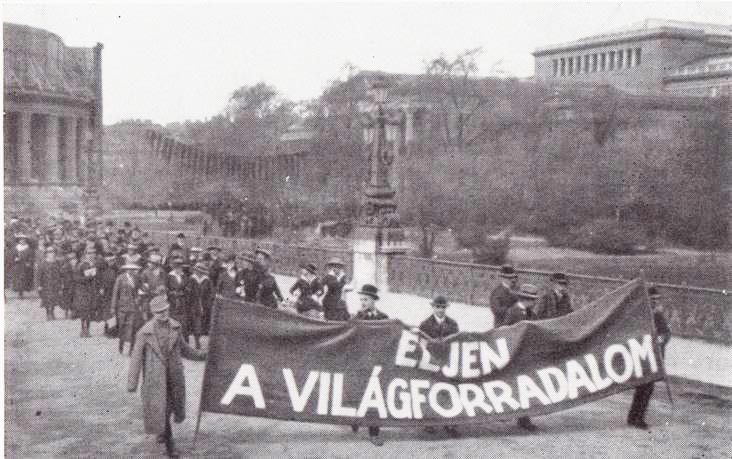

Decisive weeks in the history of mankind have arrived. The wave of enthusiasm over the establishment of a Soviet Republic in Hungary had hardly passed when the proletariat of Bavaria got possession of power and extended the hand of brotherly unison to the Russian and Hungarian Republics….To fulfil our international duty, we must first of all smash the bands of Kolchak. To support the victorious workers of Hungary and Bavaria, to help the revolt of the workers in Poland, in Germany and throughout Europe, we must establish Soviet power definitively and irrefutably over the whole extent of Russia.1

When Trotsky spoke those words, Russia no longer stood alone. On March 21, workers’ revolution had come to Budapest and Soviet power was proclaimed. The Soviet Republic of Hungary joined with Soviet Russia in attacking the bastions of bourgeois power and showed the possibilities of a new socialist order. Unfortunately, Soviet Hungary did not last long and was toppled after only 133 days by the armed power of the internal counterrevolution and imperialism. Those were not the only causes of Soviet Hungary’s defeat. Poor Communist leadership and rash policies made Soviet Hungary’s loss swifter and more certain by alienating many potential supporters. Even though the Hungarian Soviet Republic provides many negative examples of how to make a revolution, they deserve to be remembered for their boldness in attempting to accomplish the impossible in the worst conditions.

Towards the Abyss

In the years before World War One, the reign of the ancient Hapsburg dynasty over the Austro-Hungarian Empire appeared secure. The Hapsburgs had successfully co-opted potential unrest from the Magyar nobility in 1867 by creating a Dual Monarchy. The Compromise of 1867 granted the Magyar aristocracy unparalleled autonomy with control over their own government and budget. Only in foreign policy, a common army, and a customs union did the Magyars remain united with Austria.

However, this apparent success of the Hapsburgs in Hungary masked deeper centrifugal forces that threatened the Empire’s stability. By the turn of the twentieth century, a fifth of Hungarian land was owned by just three hundred families. The question of land was acute in Hungary since nearly two-thirds of the population worked in agriculture. Land concentration affected not only the peasantry but also the lesser nobility. Many of these new “landless gentry” looked for employment in the new state bureaucracy. Before 1867, the bureaucracy possessed only a skeletal structure in Hungary. Afterward, it expanded rapidly with the construction of post offices, schools, railways, and tax collectors.2 According to the historian Perry Anderson

“The Hungarian nobility henceforward represented the militant and masterful wing of aristocratic reaction in the Empire, which increasingly came to dominate the personnel and policy of the Absolutist apparatus in Vienna itself.”3

The social problems of Hungary were further compounded by the fact that only a minority of the population were Magyar (or ethnically Hungarian). In 1910, out of Hungary’s population of 21 million, only 10 million were Magyar. The majority were Croats, Slovenes, Romanians, Germans, Slovaks, Serbs, Ukrainians, and Jews. Jews formed less than 5 percent of the population, but they were heavily concentrated in urban centers such as Budapest (forming one-fifth of the populace). Many Jews played key roles in industrial and cultural life, fostering the growth of “popular” antisemitism. Antisemitism would be further exacerbated among the aristocracy and the peasantry by the fact that future leaders of the Hungarian Soviet Republic such as Georg Lukács, Béla Kun, József Pogány, Tibor Szamuely were Jews. Thus, the unresolved national question had revolutionary potential in Hungary.

The Compromise of 1867 benefited the Magyar nobility immensely. They gained a great deal of power and privileges that they had no intention of surrendering. The nobility ensured that both non-Magyar and the lower classes were denied any democratic rights. In 1914, only six percent of the population had the vote. William Craig explained the dilemma of the Hungarian nobility as follows: “Pretending to be Magyar, it gave no political rights to the Magyar peasants, the bulk of that nationality. Pretending to be liberal, it gave no political voice to the non-Magyar nationalities, very nearly a majority of the population.”4

The Dual Monarchy created a situation that Trotsky would characterize as combined and uneven development.5 On the one hand, it reinforced the weight of absolutism, feudalism, and the oppression of national minorities. On the other hand, it enabled the rapid expansion of capitalism and the creation of a bourgeoisie in Hungary. However, this bourgeoisie was not prepared to play a revolutionary role. For one, the development of capitalism was facilitated by Austrian and foreign capital, meaning the Magyar bourgeoisie was dwarfed by them. Secondly, the bourgeoisie was more interested in entering the ranks of the nobility than in overthrowing them. Magyar capitalists purchased large estates and married into the aristocracy. Lastly, the bourgeoisie was unable to play a truly Jacobin role because they could not rely on the working class. To do so would threaten their power and property as much as that of the aristocracy. As Michael Löwy concluded: “the real class interests of the bourgeoisie… wisely preferred the status quo to any revolutionary-democratic adventure, with all the attendant dangers for its own survival as a class.”6

Industrialization had created a modern working class. Out of an active labor force of 9 million, there were 1.2 million workers. Approximately a third of whom worked in small factories numbering between 1 and 20 workers. On top of this, 37 percent of laborers worked in factories numbering more than 20.7 At least 300,000 laborers worked in businesses with more than 100 workers and a third of them were located in Budapest.8 Thus, Hungary possessed a highly concentrated and volatile industrial working class, who possessed the potential social weight to lead both a bourgeois-democratic and a socialist revolution.

In fact, the Hungarian proletariat had a long history of militancy. In 1894, there were clashes between agricultural workers and the army in Hódmezővásárhely that left a number dead. Three years later, there were strikes in 14 counties by agricultural workers. In 1905, 1912, and 1913 the working class launched mass strikes and demonstrations for universal male suffrage. However, the Hungarian Social Democratic Party/Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt (MSZDP) was not prepared to lead a working revolution. Formed in 1890, the MSZDP based its program on the German Erfurt Program, which had the ultimate aim of socialism, but it focused on immediate goals such as achieving democratic and social reforms such as universal suffrage. In general, the MSZDP tended to embrace a reformist and legalistic strategy, which was ironic considering they were excluded from parliament by the nobility and the bourgeoisie. All this meant that the MSZDP was a marginal political force in Hungary.

The MSZDP possessed a narrowly “workerist” ideology, reflecting their base among the elite and skilled sections of the unionized working class. Thus, the party paid only lip-service to demands for Hungarian independence or rights for national minorities. The MSZDP was hostile to the peasantry, writing them off as one reactionary mass: “The peasantry is reactionary in the true sense of the word…. This… makes it impossible to enter into even temporary alliances with the peasantry.”9 Due to their reformism, mistrust of the peasantry, and national minorities, the MSZDP was not up to the task of playing a revolutionary vanguard role.

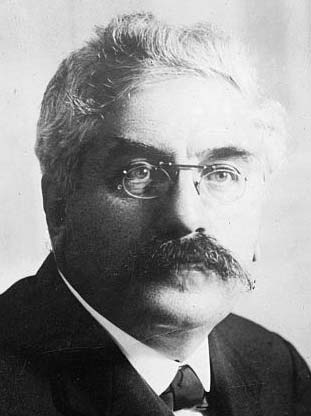

A scattered left opposition did oppose the MSZDP leadership. The most significant came from a librarian, translator of Marx, and anarcho-syndicalist theorist named Ervin Szabó (1877-1918). Szabó criticized the MSZDP’s opportunism and parliamentarism, demanding internal democratization of the party. Uniquely, Szabó advocated autonomy for cultural minorities within Hungary. He managed to exert influence upon a number of young students and founders of the Communist Party such as Jenő László and Béla Vágó.10 Vágó organized a small radical faction in the MSZDP that included other future communists, including Gyula Alpári, Béla Szántó, and László Rudas. By 1907, Szabó and his supporters were effectively isolated inside the MSZDP and driven out.

Szabó’s influence extended far outside the ranks of the Social Democratic Party. Among those who were shaped by him was a young and brilliant philosopher and future communist named Georg Lukács (1885-1971).11 While outside of organized politics before World War One, Lukács was involved in a number of philosophical and intellectual circles that were influenced by radical ideas, many of whom would later join the Communist Party.

Despite all the challenges, the Hungarian Ancien Régime resisted all calls for reform. Prime Minister István Tisza thwarted all attempts for land reform and even the most modest expansion of voting rights. While these efforts prevailed, the strength of Hungarian conservatism came not from any brilliance among the aristocracy, but from the weaknesses of its opponents. As World War One would prove, the Hungarian social order was built on feet of clay and unprepared for a great trial of strength. When the guns went silent, it collapsed like a house of cards.

World War One

When war was declared in 1914 there was mass jubilation in Hungary. All social classes shared in it, as for many the war appeared to be a chance for glory and conquest. When mass mobilization began, crowds in Budapest shouted for the defeat of Serbia. Priests blessed the soldiers marching off to far-off battlefields. Even the socialists were not immune from national sentiment. Like their counterparts elsewhere in Europe, the MSZDP abandoned its internationalist commitments and pledged their support to the government’s war effort. While the Social Democrats had no seats in parliament, there is little doubt that they would have voted for war credits if given the opportunity.

Very quickly, Hungary was on a war footing. In 1915, the army took over the management of most major industries and mines in a sort of “military socialism.” The war also brought on full employment and increased wages since skilled workers in armaments industries were at a premium and exempted from military service. Since munitions workers were determined to protect their bargaining power, the membership of organized labor increased to 200,000 by war’s end.12 However, the war economy took its toll on the home front as inflation grew and real wages plummeted. Labor shortages caused the production of fuel and foodstuffs to fall by half, leading to the introduction of rationing and the rise of a black market that benefited a small elite. Many blamed the Jews for war-profiteering and speculation. Conditions were overall appalling. Urban centers lacked new housing construction and were overcrowded due to an influx of 200,000 refugees.13 Despite the sacrifices, production failed to meet the needs of the army.

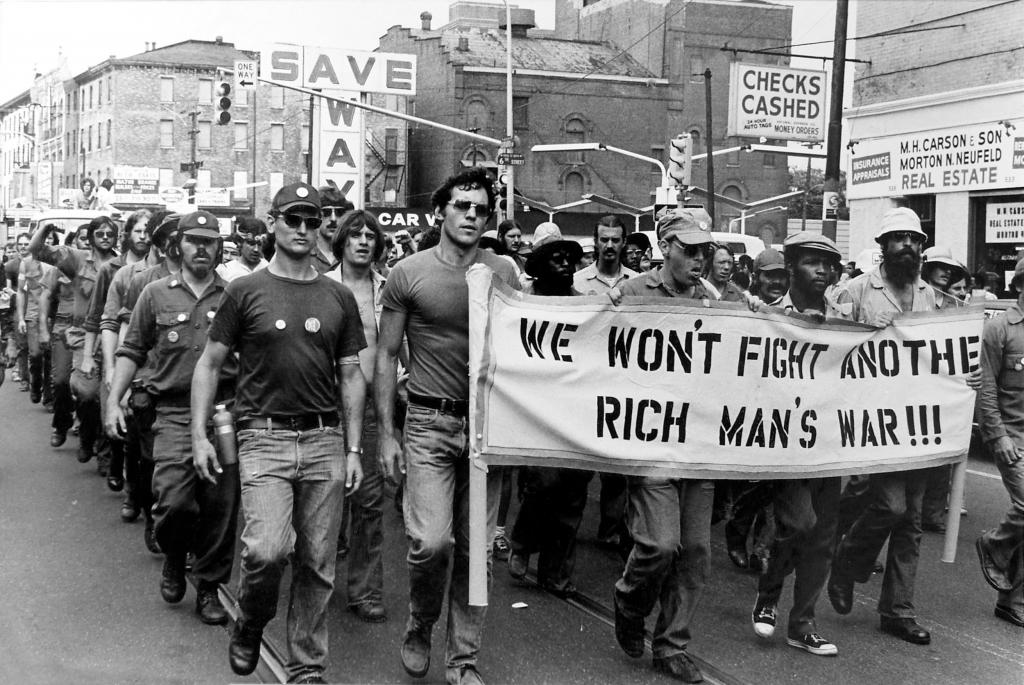

Hungary contributed disproportionately to the Hapsburg war effort. Of the 9 million soldiers Austria-Hungary drafted during the war, 4 million came from Hungary. The Hungarians suffered heavy casualties as well with at least 660,000 killed in battle, 740,000 wounded and nearly 730,000 taken prisoner.14 The heavy losses served to embitter the Hungarians, who believed they were being used as cannon-fodder. As suffering increased during the course of the war, public opinion shifted from chauvinistic militarism to disillusionment and hatred for the government.

István Tisza headed the Hungarian government during the war and was committed to victory. He also believed that victory could come without granting any major reforms. An opposition to Tisza’s conservative intransigence coalesced around Mihály Károlyi and the Party of Independence. From an aristocratic background and holding the title of Count, Károlyi broke with his class in advocating liberal and nationalist reforms. The Party of Independence vaguely supported suffrage to veterans, demands for Hungarian economic independence, and an end to the war. Károlyi himself was too radical for the party and resigned in 1916. He formed the United Party of Independence and 1848 that forthrightly supported Hungarian independence, universal suffrage, land reforms, a welfare state, and an end to the war. The new party had a base among democratic intellectuals and ultra-nationalist members of the gentry. It also formed the main parliamentary opposition. In 1917, Károlyi managed to gain support from the MSZDP for his peace and democratic reform program.15 All of this meant that Károlyi and the United Party of Independence and 1848 were now the nucleus of a future government.

Until the Soviet peace proposals of 1917, the MSZDP was doggedly committed to the war effort. Thus, any anti-war voices that appeared did so without official sanction from the party. The first anti-war socialists began organizing in 1915 when activists created a network to coordinate anti-war propaganda in the army and illegal strikes. The police clamped down and stopped their organizing. Two years later, a more serious anti-war opposition formed as socialists and labor activists among engineers, metalworkers, and technicians created their own unions to coordinate strikes and force concessions from the government. They did this without support from the MSZDP. Undaunted, these “engineer socialists” built support in a number of union locals in Budapest.16 This new center of militant syndicalism provided an invaluable organizing center for future working-class struggles against the old regime.

Another leftist pole known as the Revolutionary Socialists was created in 1917 by Szabó-style syndicalists and intellectuals from the Galileo Circle. Among their members were future communists Ottó Korvin, János Lékai, József Révai, and Imre Sallai.17 The Revolutionary Socialists were inspired by the anti-war propaganda coming out of Russia. Their propaganda highlighted real grievances and called for strikes, sabotage, and an end to the war. Arguably, the Revolutionary Socialists were the first Bolshevik center inside Hungary, not only rejecting both the status quo and Social-Democracy but also supporting a working-class revolution based upon workers’ councils.18 The Hungarian revolutionary left viewed workers councils or soviets as a real way to mobilize workers for revolution. In contrast to the reformist MSZDP and trade unions, councils organized workers at the point of production and engage in militant direct action. The Russian Revolution also showed that workers’ councils could provide the foundation for a working-class state against the bourgeois state.

On December 26, 1917, two syndicalist activists, Antal Mosolygó and Sándor Ösztreicher set up the first workers council.19 The “engineer socialists” created this council to organize and coordinate the workers for a national strike which momentum had been building up for since November as the economic situation deteriorated. To counter leftist agitation the government banned the Galileo Circle and had its members arrested for sedition.

News of the punitive terms demanded by Germany to Russia at the Brest-Litovsk negotiations ended up sparking mass strikes in Wiener Neustadt in Austria in January. Before long these strikes had spread to Hungary. On January 18, the Revolutionary Socialists and syndicalists still at liberty called for a strike. The strike was supported by railway workers and engineers, but more than 150,000 took to the streets, shouting slogans “Long Live the Workers’ Councils!” and “Greetings to Soviet Russia!” At the last minute, the Social-Democrats threw their support behind the strike, but only in order to end it. Several unions refused, notably the metalworkers’ and the rail-workers unions. Ultimately the resignation of the MSZDP from the strike’s executive committee forced a return to work.

Mere weeks later, the MZSDP held an extraordinary party congress. On the surface, it was a victory for the moderates. The party managed to contain rebellion from militant unions and the incumbent leadership was supported by an overwhelming majority. However, the party executive was no longer unchallenged and revolutionary politics were on the political map. Political polarization was only just beginning.

The January strike was only the start of social unrest. Soldiers in the barracks revolted and it was difficult for the army to send new recruits to the front. During the summer, more than a hundred thousand deserted. Over the course of the next few months, workers engaged in wildcat strikes. From June 22-27, Landler and the railroad workers launched another major strike, demanding wage increases. Soon a million workers were in the streets of Budapest. In response, the government had Landler arrested. Once again, the Social-Democrats joined the strike but ended it once minor concessions were granted. Tellingly, the MSZDP did not demand the release of Landler as a condition for returning to work. The June defeat only incensed the radicals and union leaders, deepening the divide between them and the MSZDP leadership.

In early October, the socialists took advantage of the relaxed censorship and demanded universal suffrage and a secret ballot, peace based on American President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, nationalization of major industries, land reform, and equal rights for all nationalities. The MSZDP’s program for a “People’s Government” was denounced by the revolutionary left as too little, too late.

While the divide between moderates and revolutionaries in the MSZDP was deep, it had not yet been consummated in a formal split. The revolutionary left lacked a coherent program to rally around. The split would finally come in late November when a prisoner-of-war named Béla Kun returned from Soviet Russia to provide guidance to the revolutionary left.

Béla Kun

During the war, Austria-Hungary experienced its heaviest fighting in Romania and Russia where millions died. At least 10 percent of the Austria-Hungarian army was taken prisoner there, including 600,000 Hungarians.20 Among them was a conscript and former socialist journalist named Béla Kun (1886-1938), who was captured in 1916 and sent to a POW camp in Tomsk. He would prove to be in the right place at the right time.

As the Russian Empire collapsed in revolution, thousands of Hungarian prisoners including Kun were attracted to Bolshevism. In April 1917, Kun befriended members of the local soviet and expressed his desire to work with them on behalf of the socialist cause. In an article written around this time, Kun explained his attraction to the Russian Revolution:

Although I worked for the common cause far from the Russian comrades, I too absorbed the air of the West, where the great ideas of social democracy were born. Now, in the light of the Great Russian Revolution, I understand: ex oriente lux.21

Kun was quite a catch for the Tomsk Soviet and proved to be energetic, talented, and dedicated. He was a “jack of all trades” who wrote for the leftist Novaia Zhizn on foreign affairs and organized Hungarian POWs in support of the revolution. After the October Revolution, Kun was transferred from Tomsk to Petrograd, where he began working for the International Propaganda Department of Foreign Affairs under Karl Radek. There, he worked with the Bolsheviks to conduct antiwar propaganda amongst German troops at the Brest-Litovsk peace negotiations. He also continued his agitation among prisoners of war scattered throughout Russia.

Once the negotiations at the Brest-Litovsk broke down in February 1918, the Germans launched a major offensive against Russia. Kun attempted to rally Hungarian prisoners to fight on behalf of the Bolsheviks. Even though Russia signed a humiliating peace treaty, Kun’s efforts to organize Hungarians continued. After the Bolshevik seizure of power, Hungarians were fighting for the revolution. Due to the efforts of Kun about 80,000-100,000 more Hungarians enlisted in the Red Guard to defend the Soviet Republic in the Civil War.22 Kun himself served in an internationalist unit that defended Moscow, where he helped to put down an abortive putsch by the Left Socialist Revolutionaries in July 1918.23 Over the next three months, Kun fought in the Urals, commanding a Red Army company and, later, a battalion.24 He proved himself to be one of the most valued, talented, and influential foreign socialists in Soviet Russia.

Kun’s efforts to organize the Hungarian POWs inspired similar endeavors by the Bolsheviks among German, Czech, Serb and Romanian POWs. Lenin believed that they were naturally sympathetic to communism, but their sympathy had to be translated into action. The Bolsheviks hoped that the POWs would not only serve in the Red Army but act as “carriers” by bringing international revolution back to their homelands. While the Bolsheviks had mixed results among the various nationalities, their efforts among the Hungarians proved to be quite successful. In March 1918, a core of communists was created among the Hungarians and they formed a Hungarian section of the Bolshevik Party.

It was the plan of Kun and his close comrades, Tibor Szamuely and Endre Rudnyánszky, to train cadre for a return to Hungary in order to foment revolution. From March onward, a series of meetings were held in Russia for the purpose of forming the Hungarian Communist Party, which was established on November 4 in Moscow. Between May and November of 1918, the Hungarians organized an educational program to provide a crash course in communism. Five seminars were held in Moscow on a variety of themes ranging from the ABCs of communism, the Marxist theory of value, imperialism, and the Russian Revolution. Kun, Szamuely, and Kráoly Vántus taught most of the lectures. One hundred and twenty agitators were trained and 100 of them returned to Hungary in November. Despite their small numbers, they proved invaluable in laying the foundation of an organized communist party in Hungary itself.25 Considering the chaotic situation in Hungary, Kun and the Bolsheviks believed it was imperative for the Hungarians to return home with all due haste.

Kun left Soviet Russia on November 6 along with 250-300 Hungarian communists. They were only a drop among the approximately 300,000 prisoners, who returned to Hungary in the closing months of 1918. Kun and his comrades used false documents and had little trouble crossing the border.26 Their revolutionary work was just beginning.

The Chrysanthemum Revolution

By September, military defeat for the Central Powers was no longer in doubt. The German offensive on the Western Front had failed and the Allies were advancing everywhere. The Hapsburg Empire was beginning to come apart as various nationalities prepared to secede. Rather than fight for a lost cause, Hungarian soldiers at the front spontaneously refused to fight and the mutiny quickly spread to the entire Hungarian army.

On October 16, in an effort to placate the Allies and save the Austro-Hungary from collapse, Emperor Karl I declared that he accepted the principle of federalism. The Hapsburgs planned to create a series of national councils composed of German, Czech, South Slav and Ukrainian, who would cooperate with the Imperial government. This last-ditch effort could not save the Hapsburgs. Over the next month, the Romanians, Czechs, Southern Slavs, and other nationalities seceded and formed their own states. The end of Austria-Hungary was all but an accomplished fact.

Interestingly, Karl I’s proclamation exempted the Magyars and ensured the territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Hungary. Even at this late date, the Magyar ruling class still hoped to preserve Greater Hungary without granting any autonomy to the subject nationalities. As Austria-Hungary collapsed, the Hungarian government declared the 1867 compromise null and void. They declared that Hungary had regained full sovereignty. The revolt from below meant the old system of aristocratic government was no longer viable. The only political alternative now was a democratic republic, which the Magyar ruling class had rejected for generations. There was only one figure with genuine democratic credentials who could lead a Hungarian republic: Mihály Károlyi.

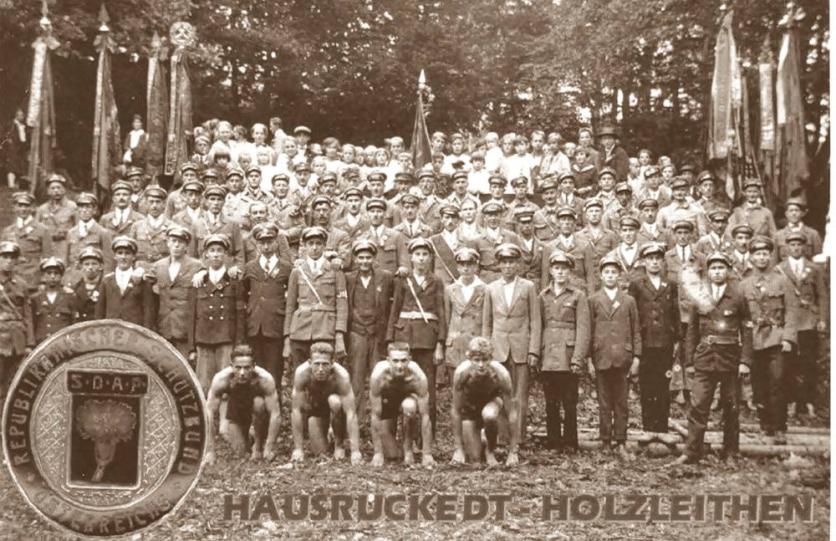

The new government took shape in a meeting held on October 23-24 at Károlyi’s mansion. The attendees included representatives of Károlyi’s party, the small Radical Party led by Oszkár Jászi and the Social-Democrats. The following day, the three parties announced the formation of a National Council which was effectively a new government-in-waiting. The National Council released a progressive program of democratic and social reforms, national independence, an end to the war, land reform and a more equitable distribution of wealth.

It was a shrewd and brilliant move to include the MSZDP. Unlike the other parties, the socialists possessed the sole organized force in the country with its one million strong trade union constituency. The socialists had no intention of launching a socialist revolution but could use their apparatus to provide legitimacy to a bourgeois one. This coalition of liberal aristocrats, middle-class reformers, and opportunist socialists, was heterodox and unwieldy, but also the only social force who saw themselves as capable of filling the political vacuum.

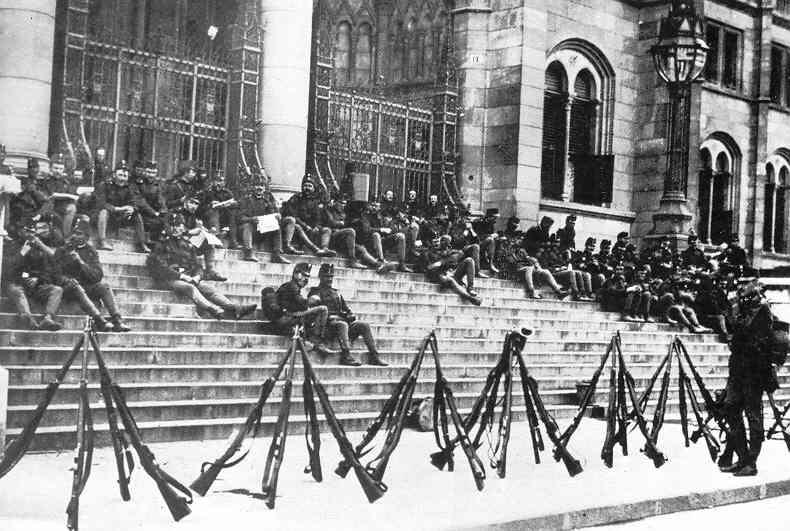

Emperor Karl I hesitated to recognize the Hungarian National Council. Instead, he appointed Count Janos Hedik, as Prime Minister of Hungary on October 29. On October 30, Hungarian troops showed their lack of confidence in Hedik by taking over strategic positions in Budapest. The following day, Hedik resigned and Károlyi was appointed Prime Minister in his stead. The Hedik government lasted barely two days. There was jubilation in the streets of Budapest with many of the troops wearing white chrysanthemums. The white chrysanthemums were popular this time of year for All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. In turn, the chrysanthemum became the symbol of the victorious revolution.

The Interlude

It appeared that Hungary had all ingredients for a successful bourgeois-democratic revolution: the transfer of power was peaceful and bloodless, the majority of the population gained the vote, and the government was supported by both liberals and leftists. However, the very circumstances that had allowed the Chrysanthemum Revolution to occur meant it had limited chances to fulfill its program.

For one, Károlyi’s government inherited the defeat and ruin left by the Hapsburgs. Even though an armistice was signed with the Allies on November 3, this contained no agreements on Hungary’s borders. In fact, French, Romanian and Yugoslav armies continued to threaten Hungary from the east and south. Ten days later, Károlyi signed a further armistice that deprived Hungary of more than half of its former territory. On top of this, there was no longer an army to defend the frontiers, with only scattered units around to offer any resistance. As time wore on, Magyar nationalists believed that Károlyi was incapable of defending Hungary. The Allies showed no concern for the Hungarians but appeared only interested in punitive measures, which only served to undermine Károlyi’s government.

Nearly as threatening as the territorial losses and the armistice negotiations was the catastrophic economic situation at home. Due to territorial changes, only about one-fifth of coal mines remained inside Hungary’s new borders. Thus, fuel and electricity were rationed in Budapest, which forced businesses to close early. The dire state of transport meant food rotted in the countryside and could not be sold in the cities. As a result, starving workers launched food riots. Inflation was rampant. Unemployment skyrocketed with the return of prisoners of war and an influx of refugees. The Károlyi government had no plans to reconvert industry to civilian production. The situation in Hungary was like the war had never ended since the Allied economic blockade remained in force.

Károlyi’s government was unprepared to handle these manifold crises. Most of them had little to no experience in government. They were forced to rely upon the benevolent neutrality of the old state bureaucracy and the officer corps. Nor did the government have much legitimacy outside of Budapest. Both the United Party of Independence and 1848 and the Radical Party had no mass support or political organization. The only group that possessed both was the socialists. According to Rudolf Tőkés: “The government… could not implement a single major decision… without the tacit or expressed consent of the socialists.”27

However, the Chrysanthemum Revolution placed the socialists in a dilemma. On the one hand, they had the support of organized labor and could potentially use that base to take power, nationalize industries and carry out a socialist program. On the other hand, they could use their power to consolidate a bourgeois-democratic revolution. The MSZDP leadership refrained from taking power and decided to enter the government as a responsible junior partner.28

Beyond its influence in the trade unions, the socialists held commanding positions in the workers’ councils. While Károlyi formerly controlled the reins of government, genuine power was in the hands of the councils. It was important that the MSZDP use its influence in the councils to halt any radical impulses. Out of 365 delegates to the councils, the socialists held a commanding majority of 239. The socialists’ power was so great in the workers’ councils that they were able to exclude the revolutionary left from them in November. The radicals only managed to hold onto a small audience in the soldiers’ councils.29 While the MSZDP kept the councils loyal to the government, other ideas developed. As the economy collapsed, workers found themselves more and more drawn into managing industries with thoughts of workers’ control. The socialists planned to use their control of the workers’ councils to restore production. In November, Zsigmond Kunfi, one of the socialist members of Károlyi’s cabinet called for a “six-week suspension of class struggle.”30 However, calls for calm and restoring production seemed like a cruel joke to workers as the economy and their livelihoods disintegrated.

Learning nothing from the example of the Russian Mensheviks, Hungarian Socialists supported a democratic government where they shared blame for its decisions. Many socialists believed that the MSZDP had relinquished its socialist program in order to befriend its bourgeois allies. Many workers also distrusted a government that was controlled by aristocrats and capitalists. As the failures of the Károlyi government mounted, the party’s base and the councils began to look elsewhere for solutions.

The Hungarian Communist Party

On November 24, the Hungarian Communist Party (HCP) was officially founded in Budapest. Béla Kun was the acknowledged leader of the new party. The new central committee included thirteen members, including former POWs such as Vántus, György Nánássy, and Szamuely (who headed an alternative central committee). Among the party’s founders were left-wing socialists such as Korvin, Béla Vágó, and Béla Szántó.31 The new HCP’s program was uncompromisingly revolutionary: demanding an end to class collaboration, exposing the right-wing leadership of the MSZDP, nationalizing estates, creating unemployment insurance, workers control in the factories, alliance with Soviet Russia, and a dictatorship of the proletariat based upon the workers’ councils. As Béla Kun’s biography György Borsányi said of the party: “In summary we may state: the organizational principles of the new party were underdeveloped, its ideology was messianic.”32

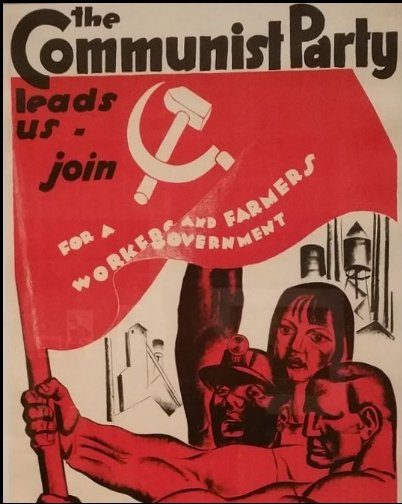

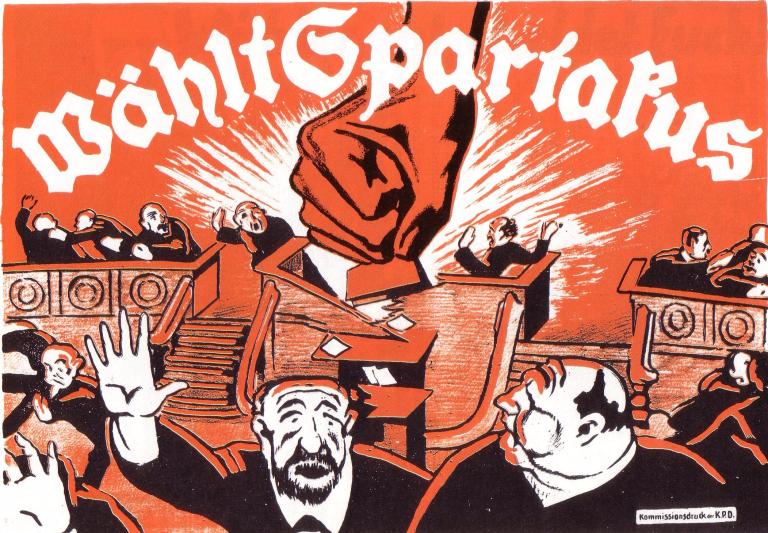

Unlike the MSZDP, the HCP was not a parliamentary vote-catching organization, but a dynamic and youthful organization committed to revolutionary action. They began publishing a newspaper Vörös Ujság (Red Journal) to reach the broader populace. Kun and the HCP were uniquely placed to rally all forces of the radical left to their banner and fan the flames of discontent. Despite its small size, the opportunities for the HCP to grow were immense.

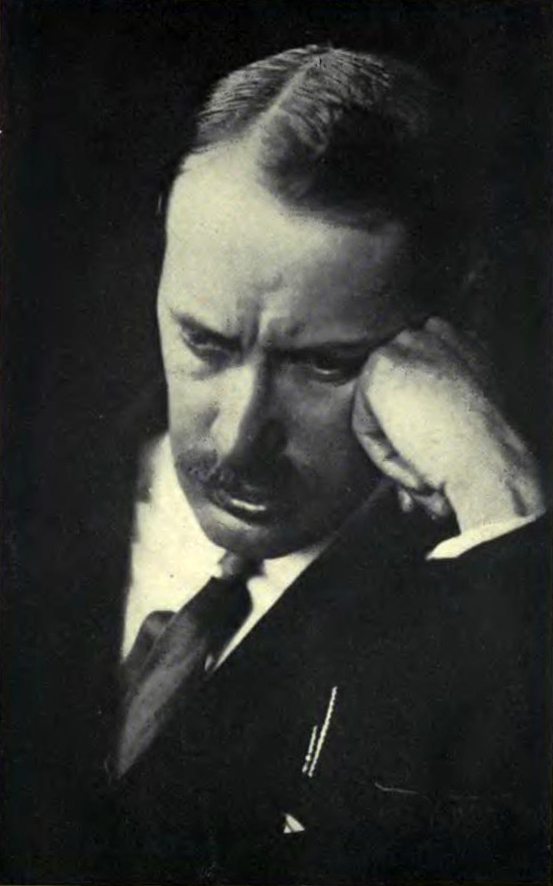

Georg Lukács

Among the earliest adherents to the HCP was Georg Lukács, who became its most internationally renowned member. Lukács had long stayed away from organized politics in exchange for literary and philosophical pursuits. He was a romantic anti-capitalist and opposed to the war, but saw no social force capable of creating a new order. Lukács viewed the MSZDP as irredeemably bourgeois. The success of the October Revolution made a deep impact upon him, even though he found many of the Bolshevik’s tactics to be abhorrent. In November 1918, Lukács wrote “Bolshevism as an Ethical Problem” expressing his central objection:

We either seize the opportunity and realize communism, and then we must embrace dictatorship, terror and class oppression, and raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class in place of class-rule as we have known it, convinced that – just as Beelzebub chased out Satan this last form of class rule, by its very nature the cruelest and most naked, will destroy itself, and with it all class rule.33

However, Lukács passed quickly from his abstract ethical objection of Bolshevik violence after reading Lenin’s State and Revolution and attending communist meetings.34 During this same period, he met Béla Kun, who explained the need to use revolutionary terror and violence. Lukács accepted Kun’s arguments on the necessity for revolutionary violence, saying later:

… we Communists are like Judas. It is our bloody work to crucify Christ. But this sinful work is at the same time our calling: only through death on the cross does Christ become God, and this is necessary to be able to save the world. We Communists then take the sins of the world upon us, in order to be able thereby to save the world.35

Twelve days after the Communist Party was founded, Lukács officially joined as its fifty-second member.36 He was co-opted onto the editorial board of the party’s journal Internationale and became a member of the alternative central committee.

The Road to Power

Over the course of the following months, the HCP grew from a tiny sect into a mass party and, finally, the second communist party in the world to take state power. The HCP was aided not only by the revolutionary situation in Hungary; they had a clear goal and worked methodically towards it. Vörös Ujság was an organ ideally suited to agitation on a mass scale. By contrast, Internationale, lectures, and seminars appealed to artists, writers, and intellectuals. Lastly, the communists were utterly dedicated to spreading the revolutionary message throughout the country. Kun himself was able to deliver twenty speeches a day. As József Révai observed: “There was hardly a worker who was not at some time and in some way exposed to communist propaganda.”37

Over the next few months, the HCP went to work. The HCP targeted selected groups whom they believed were open to radicalization, such as unionized workers in heavy industry, particularly miners and steelworkers in Budapest. They also hoped to win over the soldiers’ council and the unemployed. It was not simply that all these groups had grievances, but the cautious tactics by the MSZDP and the union leadership had disillusioned militants. While the socialists remained committed to its middle-of-the-road course, a great deal of its rank-and-file were dismayed with the party’s moderate stance. They grew fascinated by the Communist élan and that history appeared to be on their side. Considering the economic breakdown in Hungary, many workers began to doubt the possibilities of democratically reaching socialism. Only the communists seemed to promise something more than accommodating the bourgeoisie. Despite the HCP’s rigid qualifications for membership, these were often ignored in the breach. As a result, the party grew from 10,000 in January to 25,000 in February, with 10,000 located in Budapest alone.38 At the beginning of January, the communists took over the Young Workers’ League, which had previously been under MSZDP leadership. Even though the HCP only managed to recruit a small minority, it was both vocal and active.

By January, there were calls inside the workers’ councils for the creation of a purely socialist government. While a compromise plan was adopted that doubled the socialist membership in Károlyi’s cabinet, it was clear that the MSZDP leadership was divided. The HCP did not hesitate to exploit these divisions, calling for a split:

We do not intend to push the Social Democratic toward the left…but rather to help the revolutionary elements break away, so that the reformists and the believers in legal methods would be isolated. We must push he reformists to the right, by splitting off the revolutionaries and uniting them in the [Communist] Party. This is the only way to enable the Hungarian proletariat to take advantage of the revolutionary situation and participate in the international proletarian revolution.39

The HCP’s call for open rebellion in the Socialist Party provoked a response. On January 28, the MSZDP used its majority in the workers’ councils to have the communist faction expelled and its members physically removed. However, the MSZDP’s commitment to the government meant that they had cleared the way for the communists to take charge of the streets.

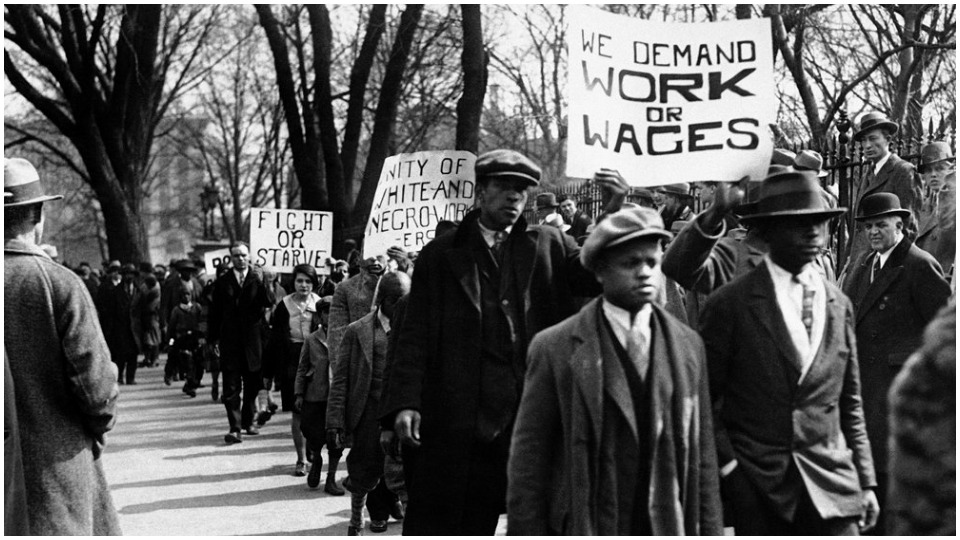

Over the course of January and February, mass struggles escalated. On January 2, a strike broke out at one of the largest coal mines in Hungary. The miners proceeded to occupy the pits, the nearby buildings, and railroad stations. The government sent in troops to put down the strike. As a result, ten strike leaders were shot. On January 22, the HCP called for a rent strike in Budapest, which prompted the government to issue a general rent reduction. Lastly, there were public demonstrations of soldiers and the unemployed in Budapest that led to violence.

The arrival of the HCP on the political scene alarmed the Károlyi government, who hoped to contain the situation. The police were granted new powers and new legislation was passed to curtail the “excesses” by the workers’ councils. In February, the government made a show of authority by moving against a number of right-wing groups and raiding the offices of Vörös Újság.

Things were not quiet in the countryside either. The slow pace of land reform led to a rash of land seizures by the peasantry. To protect themselves from the threat of revolution, the local gentry raised their own militias. In an attempt to pacify the peasantry, the Károlyi government passed a much-heralded land reform law on February 16. The law limited the size of holdings to 500 acres with compensation to be paid by the government. In a symbolic gesture to commemorate the new law, Károlyi personally divided up his own immense estate. Károlyi’s gesture did little to inspire other landowners, who remained determined to hold onto their holdings. The peasantry was disappointed in the law, believing it set the limits of estates to be too high and that the whole process of land redistribution was too slow and marred with red tape. Instead of relying upon the law, the peasants decided to take matters into their hands by occupying large estates and forming cooperatives. Ultimately, the land reform remained a dead letter.40

It was the hope of the government and socialists that their measures would provoke a response from the communists. By February, the HCP had grown enormously, but they were still far from overtaking the MSZDP, not to mention taking power. It was still possible to permanently curb their influence. That opportunity came on February 20. On that day, a communist-led demonstration in Budapest of the unemployed marched to the offices of Népszava (People’s Voice), a Social-Democratic newspaper, criticizing their coverage of the unemployed movement. A cordon of police was waiting for them and guarding the offices. The ensuing clash between demonstrators and the police left several dead and injured.

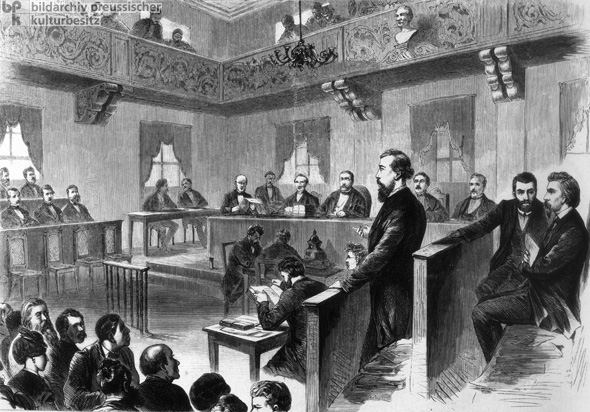

Károly Dietz, the police commissioner of Budapest, used the demonstration to demand that the government take immediate action against the communist threat. The government wanted assurances from Dietz that arrests could be carried out successfully and without sparking any backlash. After Dietz gave his assurances, the government gave him permission. That night, the police arrested forty-three leading communists, including Béla Kun.41 Once in custody, Kun was severely beaten and nearly killed by the police. By the end of the month, party headquarters and the Vörös Újság offices were closed and dozens more communists were arrested.42

The entire MSZDP, including its left-wing, supported the anticommunist crackdown. The following day, the socialists staged a mass demonstration of upwards of 250,000 in Budapest to support the government. However, the mood of the marchers changed dramatically once word reached them that Kun had been beaten. According to György Borsányi: “The impact was tremendous. Within minutes the mood on the streets had changed drastically. The shooting at the Népszava building became an insignificant misunderstanding compared to the news that the police had bludgeoned Kun to death, or at least half-dead.”43 Workers remembered the police brutality of the old regime and all that bitterness came rushing back. Suddenly, an anti-communist demonstration transformed into one sympathizing with the communists. This was exactly the backlash that the government had hoped to avoid.

Despite the arrests of the HCP leadership, its back-up central committee under Lukács, Szamuely, Gyula Hevesi, Ferenc Rákos, and Ernő Bettelheim went into action within days. Vörös Újság published again and agitators were entering the factories. As the socialist writer Lajos Kassák observed: “It was business as usual for the communists.”44 The HCP found that Kun’s martyrdom was a very effective propaganda weapon. Not only did the HCP recover quickly, but they gained mass support and sympathy from the population.

It became clear to the socialists that they would have difficulty filing charges against the communists because they would have to use the laws of the old regime. This would provide a golden opportunity for Kun to agitate against both them and the government. To salvage the situation, the government did an about-face and condemned the mistreatment of communist prisoners. Soon the communists were granted preferential treatment and Kun was able to lead the HCP from prison.

Over the ensuing weeks, the right-wing leadership of the MSZDP lost a great deal of influence. The voice of the leftists such as Pogány, Jenő Landler and Eugen Varga in the party grew. They condemned the socialist leadership for abandoning the class struggle, as well as making increased calls for unity with the communists and an alliance with Soviet Russia. The old party apparatus could no longer silence them.

On March 3, in a sign that the working class was moving leftward, the Budapest Workers’ Council voted to allow the communists to rejoin after expelling them only weeks before.45 Four days later, the council approved a plan for socialization. On March 10, the workers’ council of Kaposvar took power, posing a direct challenge to the government. In the countryside, land seizures and unrest continued to grow. On March 13, the Budapest police force recognized the authority of the soldiers’ council. This effectively meant that the last shred of governmental authority had vanished in the capital. Days later, trade unions at the Csepel iron and steel factories passed resolutions in favor of freeing the communists and denounced the MSZDP in favor of socializing industry. On March 20, a printers’ general strike paralyzed Budapest, and thousands of ironworkers joined the HCP. During the strike, the air was rife with rumors of an armed uprising to free the communists and create a soviet regime.

On March 5, an electoral law was passed with democratic elections planned for the following month. It was hoped that the elections would finally provide legitimacy for the government. While the reformist wing of the MSZDP placed faith in elections, the left was more attracted to Bolshevism. The election campaign was plagued with outbursts of violence and on March 19 the Radical Party declared its intention to abstain. As authority slipped away from Károlyi, the MSZDP’s rationale for staying in the coalition government grew more tenuous. Hungary seemed headed towards civil war.46

Károlyi’s last hope to win support from the Allies to lift the blockade in order to shore up his government vanished on March 20. On behalf of the Entente, Lieutenant-Colonel Vix arrived in Budapest, delivering an ultimatum demanding that Hungary accept heavy territorial loses to Romania and to withdraw its troops from the frontier.47 Even more, Hungary was only given a single day to accept the terms. Károlyi knew that this marked the utter failure of his pro-Allied strategy. This left Károlyi’s government in an untenable position, leaving him no choice except to resign. Knowing that a purely socialist government would succeed him, Károlyi observed that he “was handing power over to the Hungarian proletariat.”48

However, the MSZDP leaders did not believe they could govern alone. They wanted the support of the HCP and, behind them, the military might of Soviet Russia. In the negotiations, Kun demanded that the socialists accept the Communist program and transform Hungary into a Soviet Republic. Seeing that they had no other options, the socialists agreed to Kun’s demands: the fusion of the two parties and the creation of a revolutionary soviet government. There was opposition inside the two parties to the merger, but most supported a unified party. Support for the merger came from the workers and soldiers councils in Budapest. Once the deal was accepted, Kun was released from prison and formed the revolutionary government.

No doubt speaking for others of her class, the anti-Semitic writer and aristocrat Cécile Tormay described the scene in disgust when the workers came to power in Hungary:

About seven o’clock a young journalist friend came to us, deadly pale. He closed the door quickly behind him, and looked round anxiously as if he feared he had been followed. He also looked terrified.

“Károlyi has resigned,” he said in a strained voice. “He sent Kunfi from the cabinet meeting to fetch Béla Kun from prison. Kunfi brought Béla Kun to the Prime Minister’s house in a motor car. The Socialists and Communists have come to an agreement and have formed a Directory of which Béla Kun, Tibor Szamuely, Sigmund Kunfi, Joseph Pogány and Béla Vágó are to be the members. They are going to establish revolutionary tribunals and will make many arrests to-night. Save yourself don’t deliver yourself up to their vengeance.”

Even as he spoke, shooting started in the street outside. Suddenly I remembered my night’s vision . . . We are in the big ungainly house . . .the door handle of the last room is turning, and the last door opens . . .

An awful voice shrieked along the street :

“LONG LIVE THE DICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT!”49

On March 21, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed, raising the specter of the Bolshevik revolution engulfing central Europe.

The Republic of Councils

The Revolutionary Government

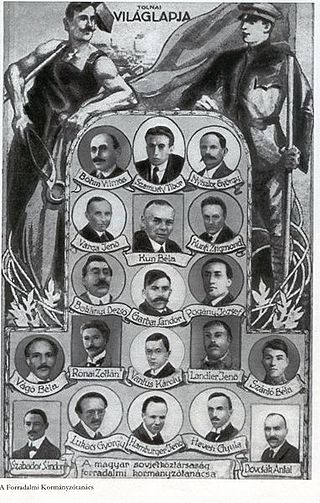

The first act of Soviet Hungary was the creation of a revolutionary government. The summit of power was located in the Revolutionary Governing Council (RGC). Following the Russian model, the twelve members of the RGC were known as People’s Commissars and the various branches of state as People’s Commissariats. In addition, there were twenty-one deputy commissars serving in the government. While none of the commissars were practicing Jews, twenty-eight of them came from a Jewish background, which reactionaries took as proof that the revolution was a Jewish plot.50

The revolutionary government itself had a largely socialist make-up. Out of the total of thirty-three commissars, socialists made up a majority with seventeen. However, many of these socialists were leftists such as Kunfi (Culture), Pogány (Defense), Landler (Interior), and Varga (Finance). Kun was the only communist to head a Commissariat (Foreign Affairs). Nine of the twenty-one deputy commissars were communists including Lukács (Culture), Szántó and Szamuely (Defense), Mátyás Rákosi (Commerce).51 The RGC’s president was a former MSZDP member named Sándor Garbai. Despite his position, Garbai held little actual power and the real leader of Soviet Hungary was Béla Kun.

Among the leaders of Soviet Hungary were journalists, philosophers, union activists, engineers, and professional revolutionaries, but the overwhelming majority had no prior experience in government. They not only had to contend with the immense problems left by the Hapsburgs and Károlyi, but had taken on the additional task of constructing socialism. The revolutionary government had little in the way to guide them, save the Russian experience, their Marxist education, and an almost superhuman belief in the communist future.

Economic and Social Measures

In their plans for the reorganization of industry, Kun believed that Hungary could improve upon the Bolsheviks, who originally followed a cautious approach to nationalization. To that end, the Soviet Republic nationalized all businesses employing more than twenty employees without compensation within a manner of days. Many smaller firms were spontaneously taken over by workers’ councils. By the end of April, at least 27,000 industrial enterprises were nationalized. This crash course in nationalization would have been a heroic undertaking in an advanced capitalist country, but Hungary was not only a backward one, but it faced economic collapse and possessed no planning infrastructure to integrate the industries.52

The Soviet Republic intended for production to be run by government-appointed commissars, who would work in consultation with the workers’ councils. In practice, the economy was disorganized with a clash of authority between unions, councils, and the government. This resulted in a decline in production, rationing, and shortages.

In a series of measures to alleviate the housing shortage, the Soviet government nationalized apartments and family homes in the cities and the countryside. To the horror of the middle class and landlords, more than 100,000 homeless workers were given shelter with their rent either lowered or canceled outright.53 Over the following months, other social measures were instituted including the right to work, equal pay for equal work, an eight-hour day, paid maternity leave, higher wages (undercut by inflation), unemployment benefits, and free medical care. Due to a lack of time, most of these measures were barely carried out, if at all. However, the Soviet Republic left an impressive balance sheet of one dedicated to defending the working class.

Institutionalizing the Revolution

Early on, the revolutionary government intended to institutionalize itself by ratifying a new constitution. On March 31, delegates from a number of district councils and party organizations approved a draft constitution for the Republic of Councils. It was the second socialist constitution in the world and as a result was heavily modeled on the Russian one. The constitution declared the “Socialist Federal Soviet Republic of Hungary,” which planned to federate with other soviet republics.54 Hungary was now a “dictatorship of the proletariat” where all power was vested in the working class and the constitution granted them rights to education, democratic rights, and many aforementioned social measures. The constitution enacted the most far-reaching democracy in Hungarian history and all men and women over the age of 18 granted the right to vote, while all members of the old exploiting classes and the clergy were stripped of suffrage. The constitutional system envisioned a vast structure of soviets at the local and district level that would make the dictatorship of the proletariat a living reality. Delegates to national-level soviets were elected indirectly at meetings of the lower level soviets. Their mandate was for six months and – in the tradition of the Paris Commune – they could be recalled at any time.55 At the highest level was the National Congress of Councils, which would elect a Governing Central Committee (GCC) as the highest organ of the state. Finally, the GCC would elect the RGC that had the power to issue decrees and was technically responsible to both the National Congress of Councils and the GCC.

On the basis of the new constitution, the local soviets held elections from April 7-10. Most of the urban candidates were industrial workers and the rural ones were largely agricultural laborers. These candidates were selected based upon a single electoral list drawn up by the unified Socialist Party. This was far from being a rubber stamp election. Many of the electoral restrictions were ignored with priests, capitalists, and landlords running against the socialists. Despite being formally united, the socialists and communists jostled with each other during the election campaign for greater influence. The results of the April elections did little to institutionalize the revolution. Only about one-sixth of those elected in Budapest were communists.56 While voting was compulsory, only 30 percent of those eligible in the cities and 10-20 percent in the villages showed up to the polls.57

In June, the National Assembly of Councils met to approve the new constitution. However, they were decidedly unrepresentative of the population. Two-thirds of the assembled delegates came from the Budapest region, and the peasantry only enjoyed scant representation. The communists composed only one-third of the delegates, but between them and the left socialists, they claimed a slim majority.58 Since the National Assembly of Councils met for such a short period of time, real authority remained in the RGC and the councils, particularly the Central Workers’ Council in Budapest. Due to the mounting external and internal crises facing Hungary, actual power came to reside more in the hands in the RGC.

Far from being a centralized totalitarian state, Soviet Hungary possessed multiple and competing centers of power such as the “united” socialist party, trade unions, Red Army, and councils. At the same time, the soviet regime faced resistance from the holdovers of the old bureaucracy, who showed little enthusiasm for the revolution or actively obstructed its directives. Perhaps with time, the revolution could have overcome these manifold problems, but time was one thing that Soviet Hungary did not have.

Power Struggle

In an April essay entitled “Party and Class,” Lukács hailed the unification of the MSZDP and the HCP as the restoration of working-class unity. According to Lukács, the unification showed that Social Democrats had “accepted without any reservations, as the basis of their activity, the communist, Bolshevik programme.”59 Furthermore, he said this was proof of the superiority of the Hungarian over the Russian Revolution because it proved “that power passed without violence and bloodshed into the hands of the proletariat.”60

In contrast to Lukács’ naiveté, Lenin was far more cautious about the fusion of the two parties. On March 23, Lenin sent a telegram to Béla Kun, where he demanded to know: “Please inform us of what real guarantees you have that the new Hungarian Government will actually be a communist, and not simply a socialist, government, i.e., one traitor-socialists.”61 Kun cabled back to Lenin that the merger was a success and assuring the Russian leader of his own paramount role in the revolutionary government as proof that the dictatorship of the proletariat had been created.62

Kun was certainly correct about his leading position in the government, but Lenin’s fears were completely justified. Many of the social democrats were late-comers to the revolution, who only supported the Soviet Republic due to expediency and not because of principle. Furthermore, due to their organizational experience, socialists tended to dominate the administrative apparatus of the party and government. As Tökés observed: “It took the Hungarian SDP just seven days to fully absorb the CP’s secretariat, agitprop apparatus and network of clandestine factory cells.”63 If anything, Bolshevik norms did not prevail in the governing party of Soviet Hungary. A left opposition of communists such Révai and Szamuely condemned the fusion as “immoral” and “spell[ing] the doom of the Soviet Republic.”64

In the unified party, Kun and the communists were a distinct minority. Before the revolution, the HCP had numbered approximately 30,000-40,000, but now they were submerged in a mass party that reached 1.5 million members.65 The new party dwarfed the pre-war social democrats as well. Many of the working-class members were no doubt enthusiastic and sincere, but also politically uneducated. No doubt many careerists found their way into the party, but on the whole this rapid expansion threatened to dilute the party’s working-class character.

Under the Soviet Republic, many new unions were organized and all their members were automatically enrolled in the party. The communists believed that this strengthened the role of the trade union bureaucracy over the working class.66 This fear was not unfounded since the union leaders did act as a brake on the radicals and kept their distance from both party and state. The growth of the unions coincided with the decline of unemployed and soldiers’ organizations, previous bastions of communist strength.67 All this meant communists had difficulty controlling the unified party organization.

The division between the socialists and communists found its way into the revolutionary government, which reduced its ability to provide clear and united leadership. In April, Kun managed to remove the distinction between deputy and full commissars, lessening the socialist majority in the RGC. This increased the number of communist commissars to thirteen out of thirty-four. At the same time, Kun also played a moderating role in the government in the hopes of gaining concessions from the socialists. As a result, he was willing to sideline radical communists: “With the cooperation of Landler, Garbai, and Bohm, Kun gradually excluded the leftists from sensitive positions in the Revolutionary Governing Council… exiling the leftists to the peripheries of power.”68 This did little to win Kun any support from the socialists and only served to alienate the communist left.

The struggle between the two factions continued at the first congress of the united party held in June. Out of a total of 327 delegates, at most 90 were communists. A majority were socialist trade union officials.69 Once more the communists were outnumbered by the socialists. Kun’s proposed program was vague enough to be adopted by the delegates without much debate. A more contentious issue arose over the party name. The socialists did not want to mimic the Russians, so they objected to the name “communist party.” A compromise was reached and the clunky name of “Party of Hungarian Socialist-Communist Workers” was adopted.

Another point of contention was on the issue of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Speaking for the socialists, Kunfi advocated a more “humane” approach and a retreat from terror and socialization.70 Discussion on the issues of national minorities was shelved. The socialists gained a victory when trade union delegates were granted voting rights that superseded those of party delegates. The election of the party executive committee showed the extent of communist isolation. They held only 4 seats out of 13.71 For the time being, the socialists and communists maintained an uneasy unity as the revolution faced its most desperate hour. In the end, the experience of the Hungarian Soviet Republic would see Lenin proven correct:

The evil is this: the old leaders, observing what an irresistible attraction Bolshevism and Soviet government have for the masses, are seeking (and often finding!) a way of escape in the verbal recognition of the dictatorship of the proletariat and Soviet government, although they actually either remain enemies of the dictatorship of the proletariat, or are unable or unwilling to understand its significance and to carry it into effect.72

The merger between the socialists and communists granted the former an unearned “soviet” and “revolutionary” facade, meaning that the working class remained under reformist hegemony. Due to the factionalism between the socialists and communists, the Soviet Republic provided inconsistent revolutionary leadership and its policies were often poorly conceived, driving many potential supporters into apathy, if not the camp of the counter-revolution. Coupled with the communists’ own mistakes, the shot-gun marriage with the socialists effectively tied their hands during the duration of the Soviet Republic. It was a fatal error.

The Peasantry

The majority of the peasants were hungry for land and determined to get it by any means necessary. If the new Soviet Republic wanted to stay in power and not be strictly urban-centered, then it was imperative for them to transfer land to the peasantry. This was precisely what the Bolsheviks had done two years before. However, the communists had no intention of doing so. Both the HCP and MSZDP were completely indifferent to the demands of the peasantry. Béla Kun, like Rosa Luxemburg, viewed the Bolshevik’s land reform as an unnecessary concession to the petty-bourgeois tendencies of the peasantry. Instead, the Soviet Republic favored nationalizing the land outright. This dogmatic approach to land reform was one of the shoals that doomed Soviet Hungary.

Kun and the Soviet government believed that Hungary was more advanced than Russia and could immediately create socialist agriculture. On April 3, the RGC nationalized all medium and large-scale estates, affecting more than half the land in Hungary.73 Considering it would take time to fully create state farms, cooperatives were set-up in the interim. The cooperatives needed capable administers to run them and ensure that production continued. However, the only ones with the necessary experience available to the Commissariat of Agriculture were the old bailiffs and owners. The Soviet’s appointment of their old oppressors to positions of authority provoked bitter resentment among the peasants, who believed that nothing had fundamentally changed.74

The Soviet’s policy to the countryside alienated all strata of the peasants. The landless peasants who worked on the new state farms enjoyed higher wages than before, but they were paid in worthless currency, sparking indignation and protests.75 Poor and middle peasants saw the government’s abolition of land taxes as the first step to nationalizing their holdings.76 Wealthy peasants were opposed to the revolution from the very beginning and the decree only confirmed their opposition.

In June, delegates of the National Association of Agricultural Workers opposed the Soviet Republic’s treatment of the peasantry. The main agenda of the conference contained no discussion on land redistribution or Soviet policy in the countryside, but the peasant delegates protested so loudly about them that the meeting was abruptly ended.77 Two weeks later, protests erupted once more at the National Congress of Councils. The delegates complained about the Soviet bureaucracy and the overzealous commissars, and they demanded genuine land reform. Urban communists, supposedly servants of bourgeois Jews, were condemned as alien to the peasantry.78 The conference showcased the unbridgeable chasm between the countryside and the city due to the Soviet Republic’s rural policies. In the waning days of Soviet Hungary, opposition to Kun’s peasant policy developed, but as Hajdu notes, it was too late by then:

In the more passive Transdanubia and the area between the Danube and the Tisza it proved easier to carry through the ideas that had the support of higher authority. Later, in the final weeks of the revolution, two corps’ commanders, Landler and Pogány proposed the division of some of the land in order to increase the enthusiasm of peasant soldiers, but it was too late by then.79

However, one must keep in mind that the Soviet Republic’s approach toward the countryside was not determined solely by ideological concerns but also by short-term expediency. The population of Budapest and other urban centers were starving. The Red Army needed to be fed in order to fight. This meant that Soviet Hungary needed to find a way to feed the urban centers and the troops. While the government seized food stocks, this was not enough and it was necessary to requisition grain from the countryside. This caused resistance from the peasantry, who either hid food or destroyed it rather than surrender their stocks to the Red Guard.80

Not all the failures of Soviet Hungary in the countryside can be laid at the feet of the government. The new regime inherited a legacy of ignorance, superstition, and feudal backwardness, which could not be changed overnight. Fear of the cities and its “godless” ways was deeply ingrained among the peasantry. Peasant fears of atheistic communism seemed to be confirmed by the communist program of secularization and attacks upon the cultural power of the Catholic Church. The Red Terror and fanatical commissars sent from Budapest only made the situation worse. As a result, the landlords, army officers, and priests who led the rural counterrevolution found willing supporters among the peasantry in the struggle against the forces of “Judeo-Bolshevism.” According to William O. McCagg:

“anti-semitism was a unifying feature of the counterrevolution in Magyar Hungary, which, oddly enough, featured efforts to bring landed gentry and peasant together on a common anti-urban ideological platform.”81

Kun and the communists’ belief that socializing agriculture would win them the support of the peasantry backfired spectacularly. They mistakenly assumed that rural class antagonisms overrode the desire for land. The communist line managed to combine the worst of both worlds: stoking fear in the wealthy peasants and alienating the poor peasants. There were few practical benefits gained in the countryside from the Soviet Republic’s laws. State farms were marked by corruption, inefficiency, and poor productivity. In many respects, Hungarian agriculture under the Soviet Republic was simply the old order painted a light shade of red. While a better approach to the peasantry would not have saved Soviet Hungary from military defeat, it would have made the victory of counter-revolution far more difficult.

Cultural Front

On March 21, Georg Lukács was in Budapest delivering a lecture entitled “Old Culture and New Culture.” During the lecture, Tibor Szamuely burst into the room and announced to the audience that the MSZDP and HCP founded the Soviet Republic. The lecture broke up as the excited crowd went out to celebrate. Only in June was Lukács able to finish his lecture, which he delivered as the inaugural address for Marx-Engels Workers’ University that he helped create. In his remarks, Lukács stated:

Liberation from capitalism means liberation from the rule of the economy. Civilization creates the rule of man over nature but in the process man himself falls under the rule of the very means that enabled him to dominate nature. Capitalism is the zenith of this domination; within it there is no class which, by virtue of its position in production, is called upon to create culture. The destruction of capitalism, i.e., communist society, grasps just these points of the question: communism aims at creating a social order in which everyone is able to live in a way that in precapitalist eras was possible only for the ruling classes and which in capitalism is possible for no class.82

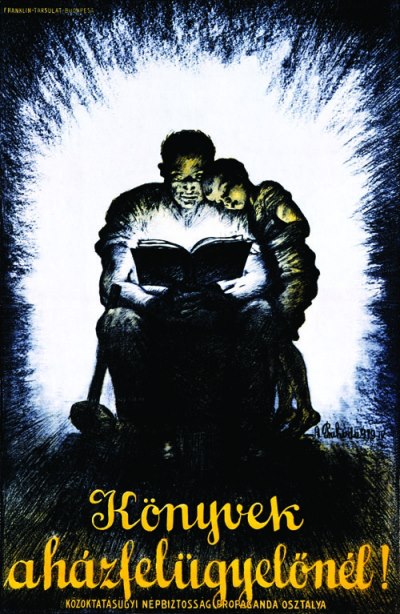

By now, Lukács was People’s Commissar for Education and Culture, and he intended to realize that vision. The Hungarian Soviet Republic aimed at was nothing less than a “cultural revolution” whereby culture would be made available to the working class. The Commissariat’s rationale was as follows: “from now on the arts will not be for the sole enjoyment of the idle rich. Culture is the just due of the working people.”83

To that end, the Soviet Republic socialized the movie industry and museums. They also confiscated the bourgeoisie’s private art collections and put them on public display on June 14.84 The Commissariat passed decrees making attendance at theaters cheap and available to the public. These performances included not only works like Shakespeare, Ibsen, Hauptmann, and Shaw, but new avant-garde plays by workers.85 During the life of Soviet Hungary, concerts and lectures proliferated.

While Lukács was devoted to the communist cause, he was no cultural philistine and possessed classical tastes. He wanted to ensure that the classics were mass-produced and within easy reach of the people. The Commissariat created mobile libraries in order to deliver literature to the workers. Lukács also commissioned translations of Marx’s Capital, Shakespeare, and Dostoevsky into Hungarian. The number of books produced by Soviet Hungary was impressive. By June 1919, 3,783,000 copies of books and pamphlets were printed in Hungarian and German along with nearly 6 million more in Croatian, Romanian, Slovak, Serb, and Hebrew.86

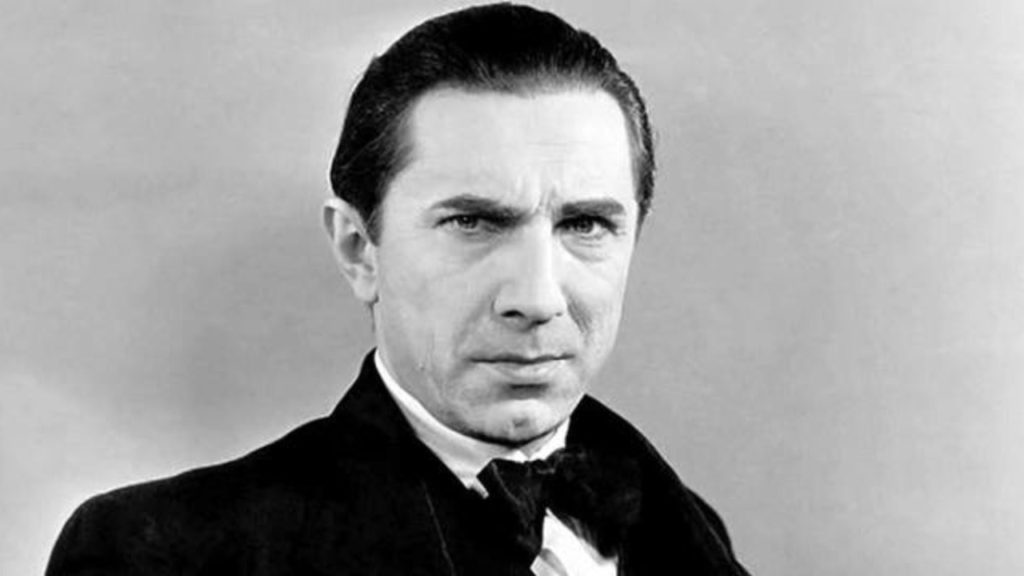

Whether musicians, scholars, painters, intellectuals, actors, or writers, there was genuine enthusiasm for the goals of the revolution. One such was the actor Bela Lugosi, later known for his work on Dracula (1931). He was one of the organizers of the National Trade Union of Actors, set up in April. In the union’s first issue Színészek lapja (Actors’ Journal), Lugosi took issue with the view that actors were not proletarians:

It is that 95 per cent of the actors’ community has been more proletarian than the most exploited worker. After putting aside the glamorous trappings of his trade at the end of each performance, an actor had, with few exceptions, to face worry and poverty. He was obliged either to bend himself to stultifying odd jobs to keep body and soul together … or he had to sponge off his friends, get into debt or prostitute his art. And he endured it, endured the poverty, the humiliation, the exploitation, just so that he could continue to be an actor, to get parts, for without them he could not live. Actors were exploited no less by the private capitalist managers than they were by the state …The actor, subsisting on starvation wages and demoralized, was often driven, albeit reluctantly, to place himself at the disposal of the former ruling classes. Martyrdom was the price of enthusiasm for acting.87

Lugosi was one of the thousands of cultural workers who saw the Hungarian Soviet Republic as the chance to make art that was no longer subjected to the imperatives of capital and to instead use their creativity to serve the people. There is little wonder why so many cultural workers, including Lugosi, were forced to emigrate after the Republic collapsed.

Despite the short life span of Soviet Hungary, it was one of the pioneers in revolutionary film production. Under director Sándor Korda, forty films were completed ranging from ones based on works with strong progress content by Maxim Gorky, Alexander Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Upton Sinclair. Other films produced included newsreels and communist agitprop.88 In April, a Proletarian Academy was set up, headed by writer and stage manager Dezső Orbán with the goal of training workers for a socialist film industry. One film the academy produced was the agitprop film Tegnap (Yesterday), which was written and directed by Orbán.89

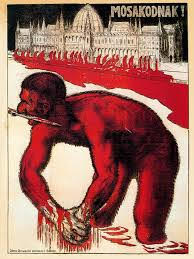

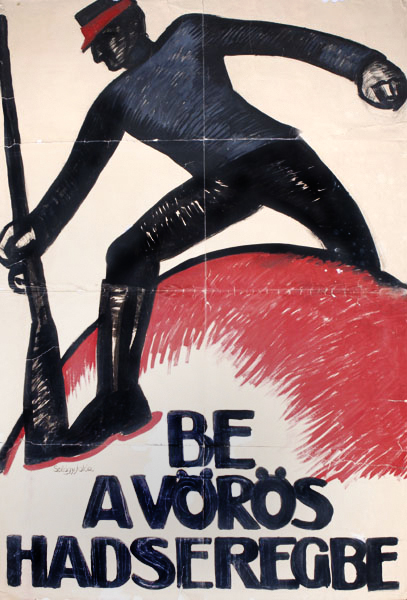

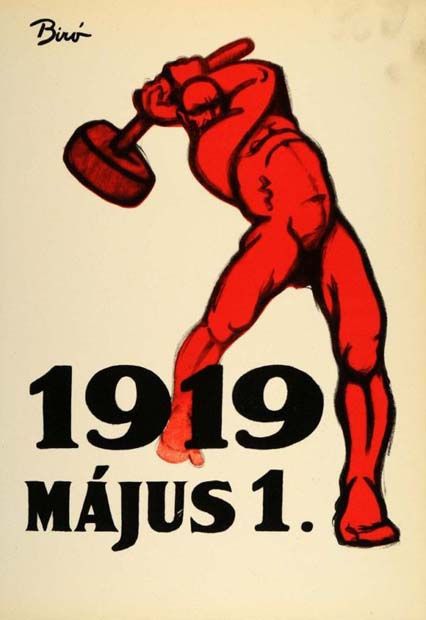

One of the ways that the Soviet Republic promoted its revolutionary goals was the use of colorful posters. According to Robert Dent, the poster was ideally suited to this task:

During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, the poster functioned as the propaganda means par excellence. Its striking power of expression and exhortation involving red, with figures in dramatic poses was recognised as being worth more than a thousand words. Revolutionary placards were everywhere, on almost every wall of almost every street. The quantity is difficult to imagine today. A large proportion were in colour, and red certainly dominated. Each had a clear message to convey and pictorially was simply presented.90

One of the biggest cultural displays of Soviet Hungary occurred on May First – International Workers Day – when Budapest was covered in red. Few expenses were spared as the RGC commissioned musicians, sculptors, writers, actors, and other artistic professions to create a true festival of communism. Slogans, posters, songs, banners, statues, and poems were located everywhere in Budapest for the historic day. A half-million marched through the city that day in a festival of the oppressed. Considering that the Soviet Republic was barely a month old and facing military disaster, the May Day celebrations showed the genuine enthusiasm of the new regime to the arts.91

Soviet Hungary not only raised the cultural level of adults but ensured the education of the next generation. Therefore, all schools were nationalized, tuition fees were abolished, and education was made free and compulsory for all until the age of 14. The Soviet Republic also instituted laws promising free medical care for all children. Schooling was taken out of the hands of the Church and controlled by the State. Lukács said it was a point of pride that children began their days with breakfast, not prayers.92 The curriculum was reorganized, dropping classical languages and emphasizing instead modern languages, and natural and physical sciences. The history curriculum was radically restructured with a new focus on class struggle, internationalism, and Marxism. Teachers were given pay raises and hastily instructed in the works of Marx, Engels, and Bukharin. The Soviet Republic believed that teachers were vital to the creation of future citizens with communist virtues. According to Commissar Kunfi: “The schools from now on will become, through the efforts of teachers, the most important institution for the training of socialism.”93

One of the most innovative education measures the Soviet Republic introduced was sex education for primary school students. To the revulsion of the bourgeoisie, children were instructed in free love, the nature of sex, and the archaic nature of the traditional family. According to one critic, Victor Zitta, the Soviet Republic’s educational policy was “something perverse” and that Lukács was a “fanatic . . . bent on destroying the established social order.”94 The hasty introduction of sex education and the severe backlash it resulted in its removal from the curriculum.95

There were severe limitations to the Hungarian cultural revolution. Due to the ever-present threat of counterrevolution, the Soviet government censored publications. Many of its cultural programs and ideas were ad hoc and too ambitious to be implemented during the brief existence of Soviet Hungary. To many of its conservative critics, the Soviet government accomplished nothing when it came to culture. The reactionary Cécile Tormay said Marxists like Lukács “kill literature in Hungary.”96 Even as the official Commissar for Culture and Education, Kunfi condemned Lukács’ approach for showing “an absolute barrenness of our cultural life.”97

These criticisms were decidedly unfair. For all its mistakes, the Hungarian cultural revolution was truly innovative. Far from destroying culture, commissars like Lukács were truly committed to ensuring that the people finally had access to it. The Soviet Republic did not impose a rigid Stalinist-style orthodoxy but rather allowed a hundred flowers to bloom. Lukács believed that everything, save openly counterrevolutionary works, should be promoted:

The People’s Commissar for Education and Culture is not going to officially support any kind of literature tied to a particular line or party. The Communist cultural programme only makes a distinction between good and bad literature, and is not prepared to throw out Shakespeare or Goethe on account of their not being socialist authors. But neither is it prepared to let loose dilettantism in art, under the pretext of socialism. The Communist cultural programme stands for the highest and purest art reaching the proletariat and is not going to allow its taste to be corrupted by editorial poetry badly used for political purposes. Politics is only the means, culture is the goal.98

In the end, Soviet Hungary showed the real potential that socialism offered in creating a new culture.

Red Terror

From its inception, the Hungarian Soviet Republic faced real threats from both internal and external counter-revolution. Based on the recent experiences of Russia, Germany, and Finland, Kun believed that terror was necessary: