Amelia Davenport responds to Jean Allen’s A Critical History of Management Thought, continuing the debate on scientific management.

Before diving into the substance of this essay, I want to thank comrade Jean Allen for their contribution to the broader discussion on the role management science plays in the contemporary ordering of production and its potential (mis)application to socialist organizing. While there are points of disagreement between Comrade Allen and myself on historical facts, we share much more common ground than might be inferred from reading their essay. In fact, there is far more common ground between Comrade Allen and me politically than between myself and the Amelia Davenport their essay presents.

To clear up some confusion, I do not support the application of Taylorism, as a framework that is articulated in the pages of Principles of Scientific Management, to either the process of production or to the socialist movement. I certainly do not believe in “uncritically applying it” or “applying it in its entirety,” No quotations are provided showing that I intended such a thing or supporting any of the claims made about my essay. The purpose of Stealing Fire was twofold: on the one hand, I sought to use Taylor as a lens to examine the pre-scientific forms of organization commonly employed on the left, but on the other hand, I turned Taylorism in on itself and expose the flawed and authoritarian character of Taylor’s original analysis. Taylorism was the name given to one of the early attempts to rationalize the labor process according to newly discovered laws of nature. In its original conception, it empowered a layer of engineers and experts who determined the best way to carry out labor tasks which eroded the power of shop floor managers, business owners, and skilled workers in favor of engineers. Instead of bosses issuing arbitrary orders and workers trying to meet them, roles and tasks were broken down into their simplest elements to maximize the potential output of machines. Stealing Fire is not a call for the adoption of classical scientific management theory but an immanent critique of it in the tradition Karl Marx critiqued David Ricardo and Adam Smith.

Likewise, contrary to Comrade Allen’s claims, I do not present an abstract science of management that socialists can simply apply to any situation, nor do I claim such a science exists. One of the most critical portions of Stealing Fire is its brief treatment of the theories of educator and philosopher John Dewey and the role practice plays in education. I emphasize learning by doing precisely because the science of organization is a practical science. What formulas I do present, like the IWW’s organizer ranking system, are tried and true methods formed out of the collective experience of the workers’ movement, not theories derived from a laboratory. The Industrial Workers of the World, through decades of experiment, developed a training system that educates its members in best practices for workplace organizing. I explore a small portion of that system which does not contain any secret tactics used for evaluating members of the target business because it is an excellent practical example of the socialist application of management science.

To make their point about the nature of organizational science, comrade Allen cites Carl von Clausewitz’s approach to military science. Few thinkers on military issues are as cited as Clausewitz besides Sun Tzu, and his book On War, lays out important theoretical tools for understanding how war and other kinds of conflict work. Breaking from old traditions that tried to create perfect models of how war “should” work, Clausewitz applied social scientific methods drawn from History and critical philosophy. He started with the reality that war involves randomness and is unpredictable.

Clausewitz, as a proto-complexity theorist, is rightly skeptical of abstract schemas that can be claimed to universally apply to military strategy. There is no textbook that can teach you war nor is there one that can teach you organizing. Here comrade Allen and I are in perfect agreement. However, Clausewitz, as singularly brilliant a mind as he was, was writing in a period before the development of the sciences that deal with exactly the sort of problems under discussion. It is also worth noting that the same objections Comrade Allen raises over the use of Taylor apply equally if not more so to Clausewitz. While Clausewitz maintained a much more flexible and dynamic vision of military strategy than his contemporaries, his vision was of a deeply authoritarian character and was inextricably linked to the ideological imperatives of the Prussian state. While Clausewitz rejected the subordination of strategy to the authority of political ministers, he also saw the army general as the singular Will for which the army is merely a body, with available autonomy of decision diminishing down the line of command until it is nonexistent at the level of the individual troop. If Taylorism was an ideological justification for an unequal society, what else could Clausewitz’s thought be? Clausewitz was an aristocratic apologist of the mass slaughter of workers for the aims of imperialist states. At least Taylor, for all his elitism, distributed authority in a collegiate fashion among managers so as to not rest in the monopolar figure of the field commander.

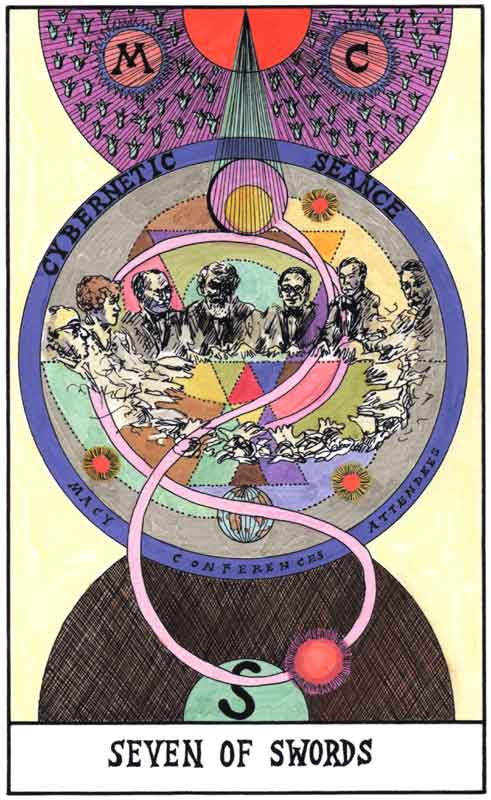

Reductionist and specialized sciences which most of us are taught in primary school certainly do have trouble generating theories that can account for highly complex, probabilistic, and dynamic processes. But that does not mean that those areas are immune to the ever-widening grasp of science. Cybernetics, Tektology, Complexity Science, Operational Research, General Systems Theory, and other paradigms have been developed to deal precisely with the invariant properties of all organizations and chaotic environments. The results of these sciences are true whether or not they are employed for one set of class interests or another. However, the implications of their findings consistently show the superiority of socialist organizational principles like autonomy, solidarity, rational planning, democracy and collectivity. Second Order cybernetics, represented by Heinz von Foerster, Stafford Beer, Francisco Varela, and others, emphasizes the active role of the scientist/observer in constructing and shaping the system of their analysis.1 It is the insights of these sciences which necessarily entails the framework of constructive socialism. Constructive socialism is not a foreordained framework brought down from Mount Sinai, it is exactly the principle that comrade Allen supports: creating the kinds of organizations that will give the working class itself the experience it needs to take power rather than continuing the path of socialisms which depend on a caste of specialist “revolutionary scientists.” Nor does it replace scientific socialism outright—it extends it beyond the limitations of the past.

As with the principle of constructive socialism, Comrade Allen misunderstands the purpose and meaning behind the advocacy of Prometheanism in Stealing Fire. Prometheanism is an ethic, not a framework of analysis. While some eco-socialists wrongly attribute the term to a blind faith in technology, it is instead a statement of libertarian socialist values. That is to say, Prometheanism is openly declaring an allegiance to the cause of freedom, to the oppressed, to understanding the world, and to the martyred dead who can no longer speak for themselves. To be a Promethean is to be willing to bear an eternity of agony rather than bend the knee for a tyrant or choose comfort over justice. To be a Promethean is to turn the tools of the masters into weapons against them, to believe in the possibility of a better world where science can serve the people. It is to accept one’s responsibilities. I utterly reject any framing of Prometheanism as scientistic or rooted in a belief in the salvific power of technology. Such a set of values is not a product of study. No length of time as a comfortable trade union bureaucrat, leftist intellectual, or political canvasser will teach these values. They come from experience, but they’re an a priori commitment a revolutionary must make. There is no science of morality, nor logical proof of its validity. But that does not mean it is not necessary. Comrade Allen is under no obligation to accept the ethic I propose, and acceptance of it is obviously not a prerequisite for engaging in working-class struggle.

Nevertheless it is necessary for members of the professional class to shed their immediate class interests in favor of their higher collective interests as members of the species. Prometheanism is an ethic which offers a way forward for the revolutionary movement as it tries to secure knowledge of the world. The Promethean ethic is best articulated by Stafford Beer in The Brain of the Firm:

But because science has indeed been largely sequestrated by the rich and powerful elements of society, science becomes an integral part of the target of protest for the artist. Each makes his own Guernica. My own view, which I set about propagating in these circles, is that science, like art, is part of the human heritage. Hence if science has been sequestrated, it must be wrenched back and used by the people whose heritage it is, not simply surrendered to oppressors who blatantly use it to fabricate tools of further oppression (whether bellicose or economic).2

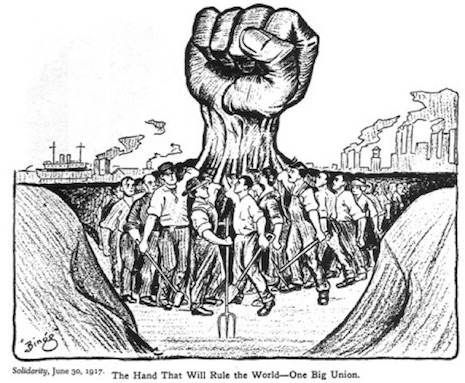

The reception of my work as a defense of Taylorism, as supporting managers, or endorsing the mental/manual division of labor (alleged by commentators less serious than Comrade Allen) is alien to what is contained within it. One has to wonder if some critical voices read Stealing Fire at all. It is decidedly ironic when Leninists and academic leftists charge me with elitism or being anti-worker control given the historical role both groups have played in the workers’ movement. Leninists, and most particularly Trotskyists, have a very long history arguing against worker control. In fact, Trotsky proposed the full militarization of labor in the USSR during debates against the Workers’ Opposition, Bukharin and Lenin over the role of trade unions. My argument that the results of Taylorism, like objective time study and safety analysis, were used by the new industrial unions for the benefit of workers against management is simply a recognition that class struggle takes place even within changed productive terrain. Workers still have agency and are not helpless objects of Capital.

Scientific managers themselves recognized the potential dual aspect of their work in the struggle of interests between labor and capital. In a debate hosted by the Taylor Society in 1917 over the use and misuse of time-studies, Navy production coordinator Frederick Coburn explained how the objective measurement of time could be used as a tool to argue against unreasonable managers and arbitrary demands:

We have found out that by carrying along the time idea that we can say to the request for immediate completion of a job, “very well, if you want that job done by Wednesday noon, here are some other jobs that must be deferred,” naming the particular jobs, and how long they will be deferred. In the old days we were told to do the job, and were expected to get that job done… 3

Coburn went further and explained that the introduction of scientific management experts meant that because they could put the objective needs of production into language the accountants and directors of factories could understand the owners could no longer “grind the neck of the working man with an iron heel” simply out of ignorance or apathy. It does not mean exploitation stops, or that the interests of capital and labor are reconciled. But anyone who has ever worked for a wage knows that a large part of the hell of work is the ignorance, stupidity and capriciousness of managers. Objectifying the work relation removes some power from lower-level management and creates a basis for resisting arbitrary authority. A manager can only demand a worker violate their company’s own “one best way” guides with some risk to themselves. Even in a society without hierarchical labor relations there will be conflicts between different interests within production and having objective standards can only serve to smooth out unnecessary friction.

Imputing motives of secret technocratic designs into my good faith treatment of Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management misses the point. By not studying or mastering the science of organization that bourgeois, authoritarian, and reactionary forms of management will re-assert themselves. These forms of organization are the social default which the general public has been conditioned into accepting. What most critics of Taylorism miss, and the reason why I made my initial contribution, is that what came before Taylorism was also bad and Taylorism emerged as a way to overcome the limits that pre-scientific capitalism had run into. These are limits that pre-scientific socialism will run into as well. When voluntarist and unscientific attempts at reorganizing the economy fail, technocratic methods of organization will be restored just like in the real history of actually existing socialism in power. The stakes are far too high to fall back on easy answers that confirm our pre-existing prejudices or allow us to write off large swaths of the accumulated knowledge of humanity. How can we defeat our enemies if we do not seriously study them? Our solutions will necessarily be far different from those presented by bourgeois theorists of management like Taylor, but we should deal with them honestly if we want to solve the problems of social and productive organization.

As Doc Burton said in Steinbeck’s classic of proletarian literature, In Dubious Battle:

I want to see the whole picture—as nearly as I can. I don’t want to put on the blinders of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and limit my vision. If I used the term ‘good’ on a thing I’d lose my license to inspect it, because there might be bad in it.

Engaging in dispassionate analysis does not mean endorsing the object of analysis.

The essay that follows is more than simply a critique of what I maintain are historical and theoretical errors on Comrade Allen’s part. It is an elaboration of an approach to history, science, and the organization of labor. It is also a defense of the materialist conception of history, developed by Karl Marx, as understood in light of contemporary advancements in our understanding of complexity and pre-modern society. The first section uses Comrade Allen’s reading of the historical development of management thought as a springboard to defend the materialist account of the role of ideology in production. The second section looks closely at the real history of scientific management in practice while exploring the nature of science and its role in society. While I hope that this essay can stand alone as a contribution to the discussion of these topics, I strongly recommend reading Jean’s essay, both for its own value and to see both sides of the debate.

Critical History or Materialist History?

Turning now to Comrade Allen’s own contribution to the discussion of management theory, they begin with a critique of Morgan Witzel’s historicization of “management thought.” Allen sketches a compelling narrative, attempting a historical materialist lens, as to why business management thought was unable to emerge in tributary societies despite the presence of widespread commercial enterprise. However, while Comrade Allen begins by looking at the structural economic factors (the ruling class existing as a landed aristocracy whose wealth is extracted by tribute rather than commercial growth), they also fall into the idealist trap set out by Robin George Collingwood’s form of historiography. Where Collingwood avoids projecting contemporary ideas and mores backwards onto the people of the past, his methodology is focused on what people thought about themselves and their world.4 Though he rejected the label Idealism because of its association with axiomatic rationalists, Collingwood’s approach is idealist in character. It pays insufficient attention to the technical and material forces of production and the real process of organizing life. Collingwood rejects the scientific approach to history that seeks invariance, that is the common aspects of things that always hold true, and sought to contextualize history within the particular subjectivity of heterogeneous epochs.5 While this style of history can create excellent fodder for use by the authors of historical fiction, and may have explanatory power for the actions of great persons, focusing on the ruling ideas of an era obscures far more than it tells us. Using R.G. Collingwood’s style of analysis, Allen says:

Simply put, the class society of feudalism could not conceive of management thinking, either as a science/means of analysis or as a justifying force in society, because it already had a justification for the hierarchy that existed within it. Often this aristocratic ideology was incapable of ‘working’ either by any objective measure or even on its own terms, but without an alternative system and a different material base, this form of magical thinking hung vestigially over society, justifying all sorts of harm and oppression despite being debunked and demystified. For centuries humanity hung between a feudal society that created all manners of useless suffering and a new method of organization that could not be spoken of let alone analyzed. This is a state I think we can relate to, and feudal notions hung onto relevance until it was felled, not by one Revolution but three.

By why did aristocratic ideology “work”? And why did it stop working In the above passage Comrade Allen answers the former question with a failure of imagination on the part of the whole of society and the latter with the bourgeois revolutions which broke the spell of aristocratic mystification. But if we want to understand management as a science, that is to say, a method of organizing the economic base, it’s precisely to the base we must look when examining its antecedents.

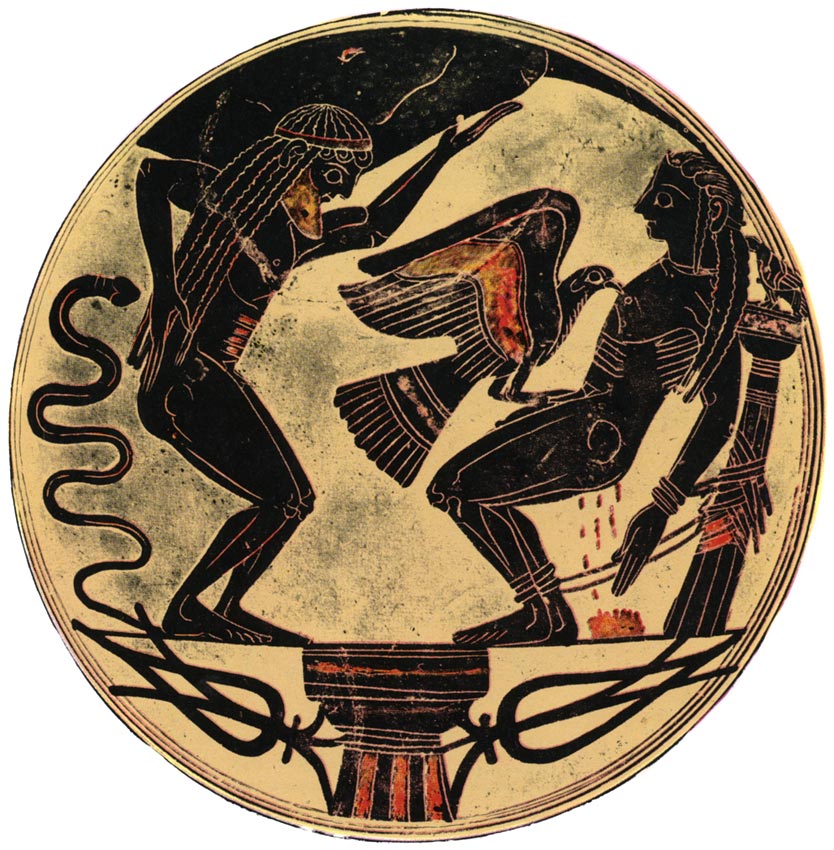

What Comrade Allen misses is that pre-capitalist production lacked a complex technical division of labor. The kinds of management thinking which preceded business management were characterized by total cosmovisions which had a place for everything and put everything in its place. As Alexander Bogdanov shows in The Philosophy of Living Experience, for most of known history and for the vast majority of society, people organized themselves within authoritarian communes where strict adherence to the accumulated traditions passed down by ancestors was essential to maintaining stability. In this set-up every aspect of the world could be understood within a coherent framework where every aspect of life was imbued with sacred significance and every phenomena was caused by some kind of will.6 Whether this took the form of innate animistic spirits, gods, ghosts, or wood goblins varied depending on the particular evolution of the people in question. It is with the introduction of trade that the unity of life began to break down. When tools and techniques arrived from outside the received traditions of the community they took on a secular character while those less productive or useful ones that had emerged endogenously were often preserved in a ceremonial capacity. While the day-to-day farming of a community might use iron tools, ritual activity would be performed with bronze or copper implements in many neolithic communities. As communities became more interconnected, the domain of secularization expanded, and was reconciled with the sacred in a new hybrid social body: the state. Imposed from a level above the commune, the laws of the state blended the mundane character of the secular with the authoritarian understanding of causality brought forth from authoritarian communism. The King’s laws carried divine sanction and represented the will of the gods, god, or ancestors but they served to regulate practical affairs and an increasingly dynamic social intercourse. Now, appeals could be made to the abstract necessity of laws rather than to divine revelation or tradition. With the rise of the new tributary society, where a sovereign authority managed the interconnection of a multicellular social body, business was born. People entered productive relations with those they had never (or would never) meet and sought out a greater share of the social surplus generated by the synergy of social elements (Bogdanov, 2016).7 As archeological evidence shows, men like the Babylonian copper merchant Ea-nasir often did so at the expense of their countrymen.8

Enterprises in tributary societies could be managed by single individuals because the level of economic complexity was very small. Success was largely characterized by luck, personal initiative, cleverness, and a predatory instinct as Thorstein Veblen notes in The Theory of Business Enterprise. Farming methods changed little across lifetimes, consumer goods required enormous investment of labor power and skill, and individuals largely remained confined to their assigned social rank and even trade. While the peasants remained exploited and oppressed by their liege, the general conditions were highly stable and regular except when struck by external shocks like disease, invasion, and famine. Moreover, even in bureaucratic systems like those which emerged in China, the primary mode of economic organization, agricultural labor, was extremely decentralized which fostered an organic corporatism. The complex Mandarin bureaucracy emerged as a means of organizing a resilient meta-systemic infrastructure for the decentralized production units to be insulated from climactic and social changes that might otherwise cause famine and disorder. Rulers would centralize and decentralize the administrative structure based on the level of stability and balancing competing political factions (Cao, 2018).9

Ruling ideologies like Confucianism, Brahminism, and Roman Catholicism were not just post-facto rationalizations of aristocratic control; the peasants were not reading ruling class ideologists. Nor did the ruling class need a metaphysical sanction for their actions: humans are perfectly capable of acts of exploiting and controlling others for their own sake. Instead, these cosmovisions were the tools which organized social reality for the purpose of labor.

While Rome did not produce much in the way of “business theory,” following their longstanding practice of appropriation from the Greeks, they did have robust theoretical frameworks governing conduct in the area. Not only did holy texts like Hesiod’s Works and Days, among others, contain advice on commercial activities (along with wise warnings regarding seductive women out to steal men’s granaries), but Aristotle wrote an entire book titled Oeconomica. While Aristotle condemns the act of making money for its own sake (what he calls “chrematistics”) he provides a clear overview of the principles which govern both household management and the management of commerce in his social context. Being situated in a culture which had extensive contacts with very different but similarly advanced civilizations like Persia and Egypt, Aristotle was able to take a somewhat objective view of the laws of economics which transcend those differences. What is crucial is that Aristotle in this book, like his others, was organizing and crystalizing the collective knowledge and techniques of his community into a coherent philosophy. This is the same role Confucius played in China. Medieval confucian scholar Sima Guang’s Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance, though focused on political management, shares much with the best of contemporary management theory from practical illustrations to deep insights in how to navigate a complex network of social relations to effectively discharge one’s duty.10 Morgan Witzel, who is the main object of Comrade Allen’s critique, denies this sort of thinking is “management thought” because it does not relate specifically to business, which Comrade Allen rightly criticizes. One of Comrade Allen’s strongest points is their discussion of the areas of unity between pre-capitalist management and capitalist management. Once the work of codifying a broad theory of management is finished, in a relatively stable society such as Rome, there is no objective imperative to develop a new cosmovision. This can be contrasted to the fractious Hellenic merchant states. Once Rome began to crumble, Roman Catholicism filled in the gap of the previously dominant cosmovision’s capacity to model and control reality. It is worth noting that while monarchs saw unruly subjects as children misled by their local liege, as Allen points out, those same subjects almost universally saw their sovereign as innately good and merely misled by wicked advisors.

But while Comrade Allen emphasizes the differences between contemporary society’s conceptualization of management and antiquity’s, they fail to sufficiently explore the differences in antiquity itself. While it’s certainly true that Chinese aristocrats maintained strong conceptions of blood purity and innate ability, that was not necessarily true of the wider Chinese society and virtue was certainly not seen as wholly innate. In Confucianism, Mohism and many other prominent schools of thought, virtue, which was inextricably tied to social managerial functions, was actively cultivated and could be far better expressed by a hardworking peasant than a decadent noble.11 In Confucian thought in particular, hierarchy was justified on the basis of necessary ritual performance, not innate qualities of blood. The noble’s social role was to be an exemplary individual and actively exercise consummate conduct in every sphere of life.12 Failing this, it was a sacred duty of advisers and potentially even commoners to remonstrate and correct the errors of the rulers lest Heaven bring ruin to society as a whole. The justification for hierarchy in China was not a top-down sanction from God, but rather a proto-Darwinistic view with the role of Heaven as the final arbiter of viability. Each noble was both a decisionmaker and spiritual guide within a distributed hierarchy, but the vast majority of administration was exercised by a merit-based bureaucracy. The “Nine Ranks” of officials in China which Comrade Allen cites from Francis Fukuyama can only very loosely be considered based on descent. They were principally determined by administrative ability but the rank of one’s father did play a role.13 This was not about the innate quality of blood, but about the perceived moral and spiritual health of the private upbringing of the candidate. A good father will raise a good son. Of course this did limit class mobility, but it was a different way of organizing social economic reality than those employed contemporaneously in Europe. It is also worth noting that the “Nine Ranks” were fairly short lived and were replaced by an examination system long before capitalism took root. Different methods of determining merit were employed in China in different periods, but it was always founded on performance rather than property. Unlike in Europe, pre-modern Chinese society largely saw what you did (within your prescribed social role), rather than who you were, as what mattered ideologically.

Most tributary societies from the Achaemenid Empire14, the Islamic Caliphate15, and even much of the Roman Empire, from Diocletian’s economic reforms until the rise of feudalism, were run principally by merit-based bureaucracies16, not the gentilshommes who directly ruled backwaters like Medieval France. Comrade Allen mistakes the existence of blood-based aristocratic systems, which were very widespread, with a universal social structure. Even India, with its caste system, was largely ruled through merit based and “individualist” managerial structures across many periods and in many regions. Whether in the Shaivist Tantrika principalities of Kashmir, the Maurya Empire of Chandragupta and Ashoka, or the Islamic Caliphate of Delhi, the Caste system was frequently overthrown or undermined as the political-economic order of the subcontinent remained in flux.17 The purpose of caste, like any other system of social classification was to structure the economic order as an active process. Today caste serves a different purpose: it is a means for opportunity hoarding. Well-off families utilize family and caste networks to better position themselves within the market economy.18 Caste persisted only insofar as it completely changed to fit the modern world. Buddhist, Jain and Islamic rulers maintained unequal systems without justifying themselves with caste, and, while they claimed spiritual authority supported their rule, differences between their regimes and those of the Brahmins can be found in how they structured the division of labor. Ashoka based his rule on freeholding farmers whom he awarded land based on right of tilling, while Islamic rulers introduced slavery to northern India.19 Spiritual texts which specified relations between the castes, toward free citizens or toward slaves were practical guides not ideological cover.

The colonial slave societies in the Americas differ from the empires of antiquity, as they did need to develop an ideological sanction for their dehumanization and brutality towards kidnapped Africans. This is because the newly emerging economic order was incongruous with the feudal cosmovision of Christianity. Christianity emerged as the ideology of slaves already engaged in class struggle against their masters.20 It was cemented in feudalism as the naturalization of a corporate relationship between the individual and the universe mediated by the church and crown. While the Christian cosmovision provided ample excuse for genocide and conquest, built up by precedent in the expansion into the lands of European pagans and defense against Islamic conquests, it stood in glaring contradiction with the principle of slavery. Christian clerics initially sanctioned this depravity by claiming it served a tutalary role, by which the “savages” would become Christianized.21 But eventually the slavers would turn to theories of racial superiority, not only as a means of “justifying” their rule, but practically enacting it and organizing the production of society. “La Casta” became a social reality for countless people. The development of secular biological sciences went hand in hand with racist control over African and indigenous labor just as much as it did with gaining greater control over our relation to our own bodies for the sake of health and general social welfare.22 A microcosm of the essential unity of this historical process is the life of the father of gynecology, James Marion Sims, who performed heinous experiments on enslaved women for the benefit of their masters. We may call things like phrenology pseudosciences today, but they were merely replaced by new ways of organizing a racialized division of labor using science. Race-based theories of intelligence and genetics continue to receive active funding by both public and private institutions. Popular scientists like Steven Pinker aren’t just doing apologism for racism—they’re creating practical models to use for organizing a racist economy.

What’s crucial here is that scientific socialists cannot take historical (or present) ideology as merely a reflection of the world that gives it sanction, nor as the driving force of human behavior divorced from the general social labor process. While ruling class ideology in our society does serve as a means to internalize control into the minds of subordinate people to avoid the necessity of deploying direct coercion, its primary function is to organize objective reality. The masses of Rome had no understanding of Aristotle or Plato but their ideas remained useful to the ruling class. Though they will have profound differences, societies that are organized around a common mode of production will share invariant properties in their cosmovisions. Feudal Japan and feudal France were worlds apart yet closer in many characteristic ways than either were to their neighbors the Chinese empire and Almohad Caliphate. This is necessary to understand why Taylorism developed. It was not a post hoc rationalization for the domination of workers by managers, but a framework for organizing society around large scale manufacturing. Taylorism is not the only possible way to organize large scale manufacture, as it is suited particularly to societies that maintain a social division of labor, but it will necessarily share invariant commonalities with a framework suited for the most egalitarian and emancipatory society which can be organized on this basis.

The nature of contingency in history is a fraught topic. It is certainly true that given a slightly different confluence of events Fredrick Taylor may have never developed his theories of management. However, contra Comrade Allen, the laws of motion of society do entail certain necessary outcomes like the development of management thought. Comrade Allen says:

The idea is that these movements occurred naturally, that the abolition of slavery or the extension of the franchise was a natural outgrowth of the birth of capitalist democracy. Hierarchical structures like slavery, the caste system, and noble privileges were economically insufficient, and thus their dissolution was inevitable. Such a construction ignores that these orders were as ideologically rooted, the deconstruction of these orders requiring revolutionary action in their time.

While it is true that revolutionary rupture was necessary to break with the old mode of production, it seems unwise to cast aside historical materialism as readily as Comrade Allen is willing to do here. Revolutions being acts of organized agency in no way violates the fact we live in a deterministic universe. The authority of the laws of physics is not delimited by a border that begins at the edge of the human mind or society. That we cannot possibly create a comprehensive model of the universe that allows perfect predictions of what will happen, (the laws of information theory, mathematics and cybernetics show why in the form of Gödel’s incompleteness theorem and Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety) does not mean that our actions aren’t determined. The dissolution of slavery, noble privileges and the caste system being inevitable couldn’t possibly be predicted with absolute certainty. The ability to make an equivalently complex model necessary for the task would only be possible for a god of equal complexity to the universe. As we have already discussed, the ideologies Comrade Allen speaks of are regulatory models for the economy and they are part and parcel with it. They’re not something distinct from the dynamics of historical materialism.

The Rise of the Technocrats

Management as a discipline emerged as a part of a much broader imperative that exists in bourgeois society: the specialization of knowledge. Comrade Allen acknowledges this phenomenon, referring to it as “siloing” but mistakenly argues that it is the result of a delusion or mistaken belief in the need for specialization:

The academic aspect of the silo effect emerges straight from management’s origins. The belief in the need for experts and the simultaneous disbelief in the importance of the lived experience of the workers creates a need for a highly specialized expert class with knowledge which is independent of the workplace, that is a managerial class with a “view from the top” rather than a view from the workplace. And at the same time, scientific management and its successors have little to say about power relationships within the workplace. This dual absence—the absence of work and power from management—has exerted a centrifugal force on the management discipline, leading to disparate sub-disciplines.

…

Instead, management takes as its focus the invented concept of the organization and how to best rule that invented concept. From this highly sterilized viewpoint, hierarchies become so necessary that they are rarely thought about. Authoritarianism in the workplace, which was so problematic in the 19th century, has been reconstructed as a battle between efficiency and equality, a battle which goes unexamined. Further syncretic knowledge is unnecessary because tasks are split into their component parts, allowing each part to be done by a specialist (a phenomenon which would not be unfamiliar to Taylor or Ford). This factory viewpoint leads to necessary overspecialization by academics and management students because cooperation between the highly disparate parts is assumed.

Before continuing the discussion of why Comrade Allen’s analysis of the atomization of work is flawed, it is worth noting that scientific managers, in particular the members of the Taylor Society, were very much concerned with the relations of power between management and labor. Beyond Frederick Taylor’s references to the conflict in Principles of Scientific Management itself, there are literally hundreds of essays and books written by Society members on the topic. Of particular note are C. Bertrand Thompson’s The Relation of Scientific Management to Labor, Man and His Affairs by Walter Polakov, and Work, Wages and Profits by Henry L. Gantt. While it is true that most practicing Scientific Managers were ideologically aligned with the rights of property, the majority who weren’t socialists were at the very least Progressive reformers within the pro-labor New Deal coalition.23

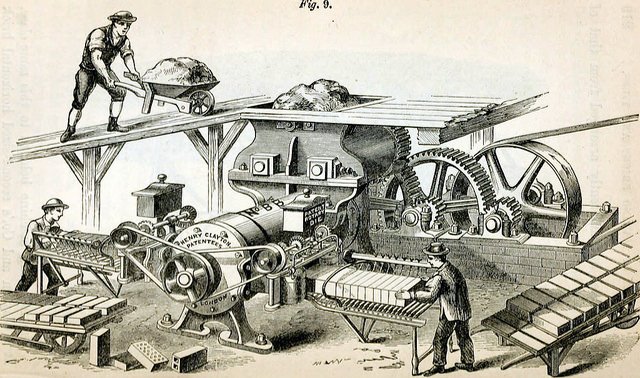

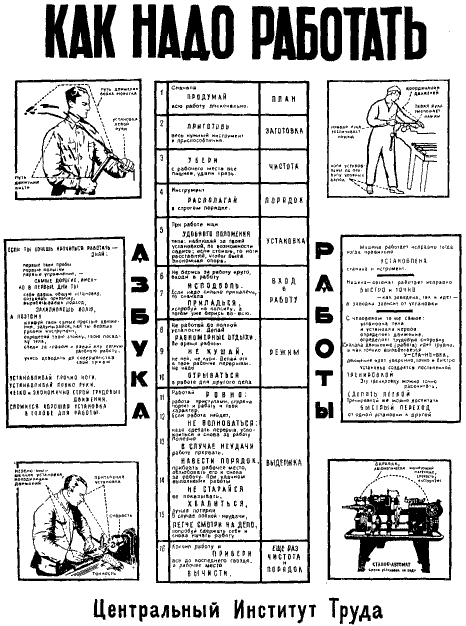

Division, reduction, pulverization, and analysis of discrete phenomena works for the needs of capitalism. It’s not just a delusion brought about by a perverse desire for control. The modernist logic of mechanical causality, which is properly studied through increasingly narrow division into incommensurate fields, was a revolutionary and progressive assault on the authoritarian cosmovision of the tributary societies.24 Where once Mankind had a unified system of knowledge, the inexorable logic of the market smashed Platonic Reason’s great Tower of Babel with an invisible hand. In its place rose a thousand tongues for a thousand new sciences. Now, rather than knowledge being handed down from God to the people through the King, any free citizen, with sufficient resources, could unlock Nature’s mysteries. By simplifying the universe into the logical models of Newton, Descartes, and Kant, humans gained real mastery over their world in meaningful ways. As the accumulated experience of capitalist society grew, these cosmovisions were translated into the practical philosophies of men like James Watt, Joseph Marie Jacquard, and Charles Babbage. The steam engine, Jacquard loom, and analytical engine were physical instantiations of the real and objectively valid principles of the modernist organization of reality. But was this kind of philosophy, this science, limited to the study of dumb matter? Or to soulless automata like the animals of Darwin’s studies? “No!” said Auguste Comte and other early socialists like Henri de Saint-Simon and Robert Owen. The methods of science, brought forth by Francis Bacon, could be applied to the study of social systems and applied toward their perfection (Hansen, 1966). Management Thought, truly applied though not yet conscious of itself, begins with Owen, not Taylor.

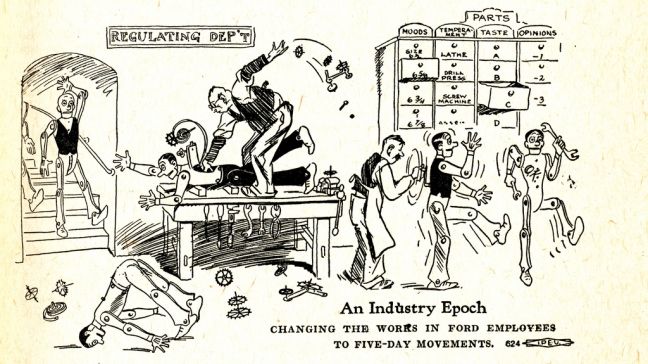

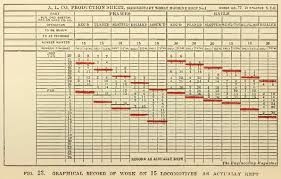

Robert Owen was a Welsh textile industrialist and social reformer born in 1771. By the end of the 18th century Owen went into a partnership and acquired ownership of the New Lanark mill as a successful entrepreneur.25 Owen is not often thought of as a “management thinker.” His proposals and social experiments took on a much wider scope than the scientific management of early pioneers (barring Lillian Gilbraith who applied the theories she and her husband developed for business with equal fervor to home-economics). But this was in part due to the context in which he worked. The spheres of social scientific study had not yet been fully differentiated. But it is also likely because of his socialist politics. Nobody doubts that Henry Ford, the pro-Nazi industrialist who revolutionized the assemblyline, was a management thinker. Yet Ford engaged in Utopian social planning himself; he created an experimental colony in the Brazilian jungle called Fordlandia and played an active role in designing the social life of the residents of Dearborn Michigan. An example of Owen’s management reforms was introducing a “silent monitor” system, in which supervisors would rate the work of an employee and display their status for all to see using a multi-colored cube placed above each workstation. Likewise he used tactics similar to labor organizers, and personnel managers, but for the purpose of winning workers to proposed technical changes, by identifying ‘champions’ among workers with social influence who he could win over as proxies to generate support.26 Owen’s utopian socialism, like that of Saint-Simon, was an attempt by the newly emergent technical intelligentsia to re-integrate society, ripped asunder by the economic laws of bourgeois production, on the basis of the conceptual framework this society had produced for the transformation of the world in its image.27 It was doomed to fail, and every community modeled on his precepts did fail, precisely because of the very thing that had given its representatives real power in the world: the social division of labor. Owen went on to become one of the founders of the British trade union movement, education reform movement, and the co-operative movement where his management theories found a more receptive audience than among his bourgeois peers and would have a more enduring impact than in the all-encompassing socialist colonies his more idealistic disciples would establish.28 It would take nearly 100 years for later researchers like Swedish-American mathematician Carl Barth, French mining engineer Henri Fayol, and Polish economist Karol Adamiecki, to transform the study of management into an institutionalized scientific discipline.

Why did it take so long for management as a field of scientific analysis to emerge after Owen? Because the technical division of labor had not yet reached the degree of development where it was possible. In Owen’s day, science itself had only recently been separated from philosophy and the broad disciplines like biology, physics, chemistry, medicine, mathematics, economics, and so on were at the genesis of their heroic periods. Other fields like psychology, sociology, and computation were a faint dream. In production, there were the “mechanical arts” rather than discrete fields like mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, and civil engineering.29 So the idea of there not being a science specifically for management prior to the general intensification of disciplinization is hardly surprising. Management science has the same relationship to earlier forms of management practice that civil engineering has to the engineering of antiquity.

Comrade Allen’s objection that management science is “unscientific” because it is ideological rests on the mistaken assumption that any science is non-ideological. One does not have to be a vulgar Marxist to see that actually existing scientific institutions are inextricably bound up with the power and interests of capitalism. Funding, institutional access, and prevailing courses of research are all heavily conditioned by the needs of both capitalism and imperialism. And even beyond this practical level, the struggle between foundational philosophies that underlie disciplines like physics are as fraught and intense as any between political ideologies. In the heroic age of physics there were sharp debates between the disciples of Viennese scientist-philosophers Ernst Mach and Ludwig Boltzmann on the existence of atoms and later Einstein’s theory of general relativity would be decried as “Jewish science” by rival physicists like Philipp Lenard. In mathematics, the debates between formalists like David Hilbert and intuitionists like Georg Cantor over whether mathematics represented true laws of reality or was merely a human construct for describing reality devolved into petty feuds and an intellectual battle to the death—until it was dissolved by Kurt Gödel’s development of incompleteness.30 And in biology, the struggle between the followers of Gregor Mendel and Ivan Michurin took a bloody turn under the leadership of Joseph Stalin. The problem with most accounts of the ideological nature of science is that they grossly oversimplify what is happening and still rely on the notion of a “pure science” beyond history that is then tainted by ideology on a practical level. This opens the door for non-scientist specialists of ideology to assert themselves as the real arbiters of truth over the scientists. Rather than demand the subordination of science to philosophy, or attempt to “free” science from ideology, the communist ought to insist that the scientist herself recognize the philosophical component, and non-neutrality, of her labor. That management science often pretends to be fully objective and neutral is not a special feature of it, and the answer is not to simply write it off because it has been used for power or because the confidence intervals of its predictions are too large. To the credit of the Taylorists, they were very open about the fact that their framework was a philosophy. This, I think, is the crux of our disagreement. Comrade Allen sees in management science a system of symbolic representation that contains falsehoods, which distinguishes it from “true” sciences that represent the world truthfully. But this kind of dualism misses the living process of science and scientists. It’s true that representation does occur within science, but it is a mechanism for gaining greater control. Science is the activity of scientists, not a commodity they produce. The lie of neutrality in science is a much deeper problem in modernity than can be laid at the feet of Taylor.

More specifically, Comrade Allen makes the case that Fredrick Taylor was a pseudoscientist because of claims made by ex-management consultant and self-admitted grifter Matthew Stewart. Unfortunately, as appealing as Stewart’s narrative is for leftists who want to dismiss scientific management without engaging with the literature, it is highly misleading. One of the claims Stewart makes is that Taylor bilked Bethlehem Steel by charging far more in consulting fees than he generated in profits from moving pig iron more efficiently.31. However, this claim depends on ignoring the fact that Taylor spent very little of his time at Bethlehem Steel focusing on the application of scientific management to pig iron at all. His true work consisted of months of conducting scientific analysis on the steel manufacturing process and transforming the management structure internal to the factory.32 In fact, Taylor’s work in the pig iron fields was primarily an attempt to appease his employer Robert Linderman. In addition to his scientific work at Midvale Steel which set him on the course for developing his framework of scientific management, Fredrick Taylor had developed a new labor incentive structure called the “differential piece-rate” system. This system, described in Principles of Scientific Management, was what attracted Bethlehem Steel’s leadership to Taylor because it promised to encourage a considerable boost in productivity with little investment of capital. Linderman was impatient with Taylor’s slow and methodical approach to time and motion studies and needed rapid results.33 While the pig iron example features heavily in Principles of Scientific Management, it’s clearly intended as a hook to draw in potential clients who would otherwise not be interested in Taylor’s system due to their natural conservatism. Using the differential piece-rate as a bait and switch, Taylor could emphasize that scientific management is fundamentally a philosophy rather than a grab-bag of techniques, and thereby begin changes to the labor process the capitalist would have otherwise never consented to. Taylor never fully implemented the differential piece-rate system in Bethlehem’s pig iron fields, as he found it unnecessary to introduce a lower penalty wage below the standard.

Turning to the claims of forgery, Stewart cites the work of Robert D. Wrege (although mischaracterizing his results), and alleges that the entire time and motion study conducted by Taylor on the pig iron operation was fabricated. But this is a result of undue extrapolation. According to Stewart, Taylor took a group of strapping workers, worked them as hard as he could without rest, and then arbitrarily decided to subtract 40% of this output to account for rest breaks. It would be comical if it were true. Taylor did not personally oversee the time and motion studies, nor did he come up with the ratio of rest to work ratio. Taylor hired a former colleague, James Gillespie, along with veteran Bethlehem foreman Hartley C. Wolle, to conduct the studies.34 From the fact that in their report Wolle and Gillespie do not provide an explanation for how they determined the 60/40 work to rest ratio, Stewart concludes that they simply made it up out of thin air. Further, the entire episode is alleged to have been a farce because very few people, excluding Henry Knoll (the real name of Schmidt) and the minority of highly able workers, were able to meet the “first rate” level of productivity which guaranteed high wages. Many workers had initially resisted transitioning to the new model because they feared a risk of losing wages if they failed to meet the productivity standards though their existing standard simply became the minimum rate. As communists, it should be clear to us that any such incentive structure implemented by a capitalist firm will ultimately be in Capital’s favor, and by the metrics of business management (that is increasing the productivity of outlayed constant capital), the experiment was a wild success.

Under scrutiny, the bleak narrative of workers driven to the bone under Taylor becomes murky. Workers who failed to meet productivity standards were almost all given other—less taxing—positions, provided they demonstrated effort.35 Similarly, part of how workers were won over to the new piece-rate system was by being offered to switch to lower intensity and higher-level work after reaching exhaustion by Gillespie and Wolle. The details of the significant work which was to define Taylor’s approach to labor in this episode, namely the “science of shoveling,” are sparse. His notes do describe creating a new kind of tool store room, figuring out optimal motions for shoveling, and there is independent corroboration of studies on shovel size. Moreover, contrary to the claims of Stewart, Taylor’s pig iron experiments were independently replicated multiple times, first by French physiologist Jules Amar and later, carefully documented on film, by Frank Gilbraith. Reviewing the footage and research conducted by Gilbraith, it is clear that the general results of Taylor’s pig iron study are correct, within a standard 5% margin of error.36 It is also true that the version of events laid out in Principles of Scientific Management contain inaccuracies. Various events are smoothed over and differ from what historical documentation says actually happened under the direction of Gillespie and Wolle. But it is important to remember that the text is a recollection intended to give color to a boring topic, not a scientific paper itself and does not contain willful falsehoods in any areas that relate to the central argument. In fact, as the research of pro-Taylor scholars Jill Hough and Margaret White shows, Taylor likely deserves none of the credit, given the study was neither original (similar studies were well documented at the time) nor did it involve his personal intervention.37 Moreover, much of the text was not written by Taylor himself. The bulk of the manuscript, in particular its theoretical core, was penned by Taylor’s protege Morris Cooke.38

Unlike Stewart, Taylor critic Chuck Wrege does provide illuminating insight into Taylor’s character, and willingness to bend the truth. Rather than demonstrating the invalidity of Scientific Management, Wrege sets out to deflate the myth of Frederick Taylor as a lone genius who revolutionized management. However, Wrege himself frequently bends the facts to paint Taylor in an even more salacious light than his unadmirable behavior creates on its own. This has allowed management gurus like Stewart, with less compunction than Taylor himself, to issue a blanket dismissal of scientific management in favor of their own “wisdom.”

It is well accepted that Taylor’s experiments were remarkably successful according to several metrics. From the perspective of capital, Taylor improved productivity threefold at Bethlehem Steel. This greatly boosted Taylor’s credibility among capitalists. From the perspective of labor, the average worker received 60% more pay than before.39 While wages did go up, the increase in wages can in part be accounted for by the high turnover the new system created which cast off unproductive (and therefore low-paid) piece workers. Most of these workers were moved to other jobs within the company, though not all. While as socialists we decry the inhuman aspect created by the iron link between employment and subsistence, this high turnover is itself a success from the perspective of the scientific management philosophy, as it enabled a more rational allocation of laborers to the places they were most suited. In a socialist society where survival is not linked to the selling of labor-power, eliminating the need for labor hours would be a benefit, not a curse. Ironically, the turnover of labor was a specific concern of the owner Linderman and the Bethlehem Steel management and a source of friction with Taylor. The company owned the homes the workers lived in and robbed them through the company stores.40 By turning over unproductive labor and rationalizing production, Taylor was disrupting the quasi-feudal debt-bondage system Bethlehem Steel had set up.

Taylor saw the factory as a machine for producing social wealth. The workers and managers were to both be molded into rationally perfected components, each playing their own specific part. This idea seems naturally revolting to those of us not indoctrinated into the ideologies which permeate engineering departments at universities. But it is hard to articulate exactly why in objective terms, leaving critics open to accusations of sentimentalism or moralism. Taylor is the ever-present foil for management theorists precisely so they can paint themselves as more able to factor in the “human element” of business.41 Even in his own day the great bulk of management publications pilloried his engineer’s mindset. But rather than such an impoverished view of productive life representing an engineering or scientific view, it was overcome already through management science in Taylor’s lifetime.

It was not Taylor who implemented the overall system in Bethlehem as he was preoccupied defending his reforms to senior management and working on specific improvements to steel manufacture. Instead, the system was implemented by his protegee Henry Gantt.42 Taylor had successfully, and quite scientifically with the help of mathematician Carl Barth, optimized much of the machinery engineers were working on, created a planning office, and created his specialized system of “functional forement.” However, productivity had not improved, and machinists simply adjusted the speed of their work to maintain the same output as before. To overcome this, Gantt, with Taylor’s approval, introduced a new piece-rate system which greatly improved on Taylor’s model. Rather than punishing workers for failing to reach a minimum threshold, like in the original differential piece-rate system, Gantt preserved the existing wage and only introduced the higher rate for meeting a higher productivity threshold. In so doing, he avoided the risk of labor unrest.

The other key difference between Gantt’s system and Taylor’s model developed at Midvale is that the machinists at Bentham were actively included in the design and implementation of the labor process. Workers understandably resented being completely excluded from the intellectual aspect of their work and would often refuse to follow the instructions provided by managers, believing that they knew better. Gantt found a way around this: if workers disagreed with guidance on their instruction card they were encouraged to write feedback and return it. If they were more effective than the instructions the managers had laid out, the planning office would adjust the instructions going forward. If the worker’s ideas were less effective, the managers could demonstrate it and win the worker over to the more effective methods.43 What Gantt had discovered is that by treating the workers as more than mere implements of science and instead as vital parts of the planning apparatus he could leverage a greater social intelligence to the collective enterprise of production. These experiences were crucial for transforming Gantt politically from a liberal into a socialist. Scientific management, as a practical science, was not limited to Taylor’s personal authoritarian approach.

The key lesson of scientific management is that “management” itself acts as a fetter on the organization of production. This is something I am sure comrade Allen agrees with. The traditional business management holds back the engineers, eschewing techniques that would reduce waste, increase output, and generate social surplus because they challenge the direct material interests of the management class. Likewise, the engineer-managers themselves, by virtue of their monopolization of expertise, are structurally incapable of realizing efficient production. For all their knowledge of scientific principles, they cannot possibly hope to manage the complexity of the labor process, without effectively ceding decision-making control to the workers. By getting rid of rule-of-thumb and artisan methods in production through scientific analysis, the scientific engineer-managers set the terms for a dialogue between the abstract and the concrete in production rather than setting in stone a “one best way” like they believed. That the Taylorist view does not accord with modern scientific understandings of complexity implicates Taylorism exactly as much as it implicates the entirety of the Enlightenment scientific project. A true organizational science, which moves beyond the horizon of bourgeois reductionism, will overcome modernity and make itself of and for the masses.

Beyond accusations of pseudoscience, Comrade Allen’s narrative of the development of scientific management rests on the myth that it was created as a tool for the bourgeoisie to discipline the rising working class. Given as support are a series of anecdotes that demonstrate a correlation in history between the rise of scientific management and the period of classical anarchism and social-democracy’s ascendance. Allen argues that the contradiction between Republicanism in the civil/political sphere and the authoritarianism of the workshop resulted in the birth of a movement that demanded an “applied republic” in the economic sphere. Scientific management is cast as an ideological tool to avoid such an outcome by tricking workers into demanding “better” management instead of democracy.

Such a tidy narrative is as compelling as it is ahistorical. While it is true that there were forces that demanded democracy, demands that are certainly worthwhile, the French workers’ movement was not so straightforwardly “Republican” in political or economic thought. In fact, many, though not all, leaders of the General Confederation of Labor, the largest, most powerful and most radical union in French history at the time, explicitly disavowed all aspects of republicanism and democracy.44 They believed majoritarianism, procedural voting and universalist politics were inherently bourgeois. Instead they called for a decentralized aristocracy of labor which would mobilize the workers through charisma in direct corporate association and build a world with unmediated and direct relations of production. Some on the left held more favorable views of democracy than others, but all agreed that the only means for workers to achieve their aims was direct struggle. Likewise, within the political social-democratic parties there was no universal demand for a republic within the workplace though some social-democrat leaders like Karl Kautsky did make references to it. The chief demand of the political socialists and the right wing of syndicalism was social control of production. Economic democracy meant disciplining production to the political democracy of the republic. Within the CGT, the leaders most aligned with the Republican tradition like Léon Jouhaux took this line and advocated nationalization with a tripartite management scheme consisting of worker, consumer and public representatives.45 In fact, Jouhaux, along with both leftist and rightist CGT members came to enthusiastically embrace Taylorism, provided it was conducted by the union in the popular interest of efficiency rather than the employers to sweat workers harder.46 It was the right-wing current of the syndicalists which most strongly identified with the French Republican tradition’s notions of liberty and progress, along with the political Socialists, while revolutionary elements sought a break with what they viewed as a great scam by men like Robespierre.47 What French syndicalism and political socialism ultimately aimed for was a “full life” for the people, and it was this which the bourgeoisie denied them. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, Democracy and Civilization were not themselves the aim; they were judged by how suited they were in providing satisfaction to the direct material needs of workers.

If economic republicanism itself does not actually represent either a universal aim of the workers, it follows that it does not make any sense to juxtapose it to scientific management theory. Fredrick Taylor’s system, completely unmodified, is perfectly compatible with the democratic election of the leadership of an enterprise. It is even compatible with democratic deliberation and voting on policy. What it is not compatible with, and this is something incredibly valuable and often stands in opposition to democracy when each is taken to extreme, is autonomy. And while autonomy has long been a demand of the workers’ movement, it is not always a universal demand and takes on a different character depending on the perspective under which one applies it. The autonomy of a labor collective freely associating and jointly engaged in production is different than the autonomy of the petty bourgeois artisan who answers to no one but himself and his clients. And though Taylor himself opposed autonomy, many scientific managers did not. Taylor Society member Edward Filene for instance, by no means a radical like Marxist Taylor Society members Walter Polakov and Mary van Kleeck, was a pioneer and key promoter of credit unions and actively supported the transition of businesses into worker-owned cooperatives.48 His vision of “economic democracy,” at least in the 1930s, was not unlike the “applied republic,” yet he was committed to the principles of a movement that was supposedly a reaction against it.

Conclusion

Most people are not opposed to applying universal principles in the labor process if it makes their life easier. We only stand to benefit from techniques that reduce the arbitrary nature of the labor process. The scientific management proposed by Frederick Taylor is obviously incompatible with communism if taken on its own terms, but for many Marxist theorists like Lenin, it contained seeds of the future form of organization in spite of itself. Which is to say, Taylorism ideologically talks about scientific truths. As will be seen in the sequel to Stealing Fire From the Gods, the rational kernel within Taylorism, separable from its reactionary content, is labor analysis. This is the breaking down of the labor process into its elements so they can be understood and improved. While not sufficient on its own terms, labor analysis is a crucial tool for the design of any goal oriented process. Taylorism is already outdated in relation to capitalist production compared to schools like Operational Research and the Toyota Way, while capitalism long expired as a defensibly progressive economic system. But this does not mean it contains no lessons. Critics who might charge that using labor analysis does not require rehabilitating Taylor, the Taylor Society, or scientific management more broadly, miss the fact that any implementation will be conflated with Taylorism regardless of our rejection of Taylor and criticisms of his philosophy. Hopefully my forthcoming account of the development of scientific management in the early 20th century in the United States, France and the USSR will serve as inspiration for the kind of thought necessary to develop an organizational science of labor beyond management.

Though this essay takes a sharp tone and gives little ground to Jean’s analysis of the history and development of management thought, I do see it as an important contribution to the debate. Their critique of Morgan Witzel’s inconsistency, advocacy of workers’ freedom, and strident opposition to managerial hierarchy are welcome and needed interventions in our society and unfortunately in much of the left. Those of us on the left who want to win have to firmly reject commandist and authoritarian methods of organizing. Jean is absolutely right to see them as less efficient and resilient than forms of organization that leverage autonomous organization. Though the danger remains far more with personalist and charismatic forms of hierarchical organization than technocratic forms in the contemporary left, we shouldn’t simply trust experts to run our organizations for us either. As stated earlier, Jean and I are very close politically in terms of values and even immediate prescriptions, but that only makes the necessity of polemic greater. Being in the same political camp means we have a duty to one another to work together toward clarity. By critiquing Stealing Fire, Jean gave me the opportunity to elaborate and clear up misconceptions about my analysis, and I hope my critique of their essay will serve them equally well.

Unlike Jean, at the risk of arrogance, I do have a vision of what kind of management will replace the authoritarian personal management of capitalism. I do not believe that we have to wait until a new framework spontaneously emerges from the political struggle of leftists. Of course a new management must emerge from practice, but the “collective mind” of humanity is much bigger than “the movement.” Within the real living history of management thought, and outside the sclerotic majority of business schools, there are repeated revolutions born out of necessity. The introduction of the assembly line, the October Revolution, World War 2, the countercultural revolution of the 1960s and other periods before and since represent moments where we can identify real science being done to re-conceptualize how humans can organize themselves economically.

There is a spirit that Stafford Beer identifies in the final remarks of his book Brain of the Firm which flows through innovative schools of management thought up to the point they reach their limits.49 Frank and Lilian Gilbreth had it, as did the founders of Operational Research like Russell Ackoff and Heinz von Foerster. Others like Beer himself and Lenin had it too. In each case what is important is the process of scientific inquiry, commitment to a vision, and a way of being in the world. In Confucian terms, it is a kind of Ren or “consummate conduct.” In other words, becoming good at being human. In this, I think Jean and I are in full accord. The specific models and theories that are created to represent phenomena are not important for defining the new management. I fully agree with Jean that we can’t find some abstract scheme to apply to solving all our problems. I reject the worldview that sees science as a form of representation; science an action. I recognize that what will replace bourgeois management is the redevelopment of management as a collective science of performance. Fortunately, some of that work is being done right now by researchers like Raul Espejo and others advancing the Viable System Model, and we have a wealth of research from both Western and Soviet scientists of organization to draw on. The new organization of labor will be a philosophy of living practice.