Lydia, Isaac and Rudy join Emmanuel Farjoun from Matzpen for a discussion on his 1983 piece Class divisions in Israeli society and how the divisions have changed in the present day. We discuss the changing strength of the Palestinians inside Israel and how that is reflected in their changing political aims, the differences between whiteness in the US and the construction of race in Israel, and the BDS movement internationally.

The Origins of Matzpen: the Israeli Anti-Zionist New Left with Moshé Machover

Isaac and Rudy join Moshé Machover, one of the four founding members of the Israeli Socialist Organization, better known as Matzpen after the name of their publication for a discussion on the group’s origins, how their anti-zionist consciousness originated and developed, their marginalization by Israeli society during the 1967 war and how Arab/Jewish solidarity was built. The conversation then pivots to how the Israeli Class Structure has changed since its early analysis by Matzpen and what that bodes for the future. They also address the topics of diasporism and how Israel compares to other settler (and non-settler) societies in the world.

Further resources:

Youtube documentary on Matzpen, Anti-Zionist Israelis

Moshé’s articles on Belling the Cat, Colonialism and the Natives and Hebrew self-determination . Check out his Weekly Worker archive.

Colonialism and Anti-Colonialism in the Second International

Karl Marx’s own ambiguous and sometimes contradictory views on colonialism meant that the Second International would debate over the correct view on the matter. Donald Parkinson gives an overview of these debates, arguing that Communists today must unite around a clear anti-colonial and anti-imperialist program.

Today, when Marxism seems to be under constant intellectual assault, we hear the claim that Marxism is a Eurocentric ideology, that it is a master narrative of the European world. It could be tempting to simply dismiss this claim on its face. After all, most Marxists today live in the non-European and non-white world, inspired by the role Marxism played in anti-colonial struggles. Yet we should always pay attention to our critics, regardless of how bad-faith they may be. They can help us understand our own blind spots and weaknesses and better understand ourselves. As a result, we should take the question of Eurocentrism seriously and engage in a critical self-reflection of our own ideas. A closer look at both the works of Marx and the history of Marxist politics tells us that there were indeed Eurocentric strains in Marx’s thought. Yet through its capacity to critically assess itself Marxism has, to varying degrees of success, overcome its Eurocentrism to develop a true universalism, against a false universalism that only serves to cover for a deeper European provincialism.

Marxism developed in Europe as a worldview designed to secure the emancipation of the world from class society. This is the source of internal tension within Marxism: on one end there is the universalist scope of Marxism, an ideology designed to unite all of humanity in a common struggle. On the other end, there is the source of Marxism in the continent of Europe, an ideology that was shaped by the specific processes of capitalist development that propelled Europe into an economic power standing above the rest of the world. It would be foolish to simply dismiss charges that Marxism contains Eurocentric elements that exist in tension with its universalism. There is no better example of these tensions in Marxism than the different views on colonialism within the movement.

Colonialism in the history of Marxist thought served as a challenge for Marxism to overcome its own Eurocentrism. Within the works of Marx one can find different approaches to colonialism that could be read as apologetic to colonial expansion or firmly opposed to it, supporting the struggles of colonized people against their dispossession. As a result, the followers of Marx who formed the mass parties that came to be known as the Second International did not have a single position on colonialism that they could take from Marx. There was instead a series of often contradictory positions on colonialism within his work that provided justifications both for supporting colonialism and opposing it. There was also a theoretical heritage within Marxism, economistic developmentalism, that would be used to justify colonialism in the name of socialism.

To better understand these tensions in Marxism, we should examine Marx’s views on colonialism and the first major debates on colonialism in the Second International. These debates are an important part of a greater historical narrative, in which Marxism developed as an ideology in Europe and became the siren song of countless anti-colonial revolts against European domination. Marxism was able to overcome its initial Eurocentrism, but not without a struggle internal to itself and its intellectuals. In better understanding the history of this intellectual struggle, we can better identify the theoretical errors that held Marxism back from becoming a truly universalist worldview, which could serve as a political creed for the emancipation of the world, not only Europe.

Marx on Colonialism

To begin, it is necessary to look at Marx’s own views on colonialism and their development over his lifespan. Marx’s views on colonialism were never straightforward, and taken as a whole can be seen as inconsistent and contradictory, leaving room for interpretation. It is this openness for interpretation that allowed colonialism to be an open question for his initial followers. Within Marx one can find, on the one hand, a view of economic development and historical progress suggesting that European colonialism was a harbinger of progress, bringing the “uncivilized world” into “civilization” by laying the seeds for capitalist development and therefore proletarian revolution. And on the other hand, one can find in the later works of Marx the beginnings of an anti-imperialist and anti-colonial politics.

In his well-known Communist Manifesto, written in 1848, Marx comes across as almost a colonial apologist of sorts, pointing to the rise of the capitalist world market as an accomplishment of a historically progressive bourgeoisie, and colonialism as a means through which this world market is established:

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.1

Referencing “Chinese walls”, Marx strongly suggests that England’s First Opium War against China was in the long run historically necessary and progressive, bringing a “barbarian nation” into “civilization”. For Marx in 1848, colonialism wasn’t so much something to be condemned and battled, as it was part of a historical process through which capitalism would conquer the world and create the necessary pre-conditions for a communist future, with all nations passing through a similar route of development. However, with time, Marx’s views on the matter would develop.

After moving to London in 1849, Marx would take up a career as a journalist and wrote a series of articles on non-western societies. One of the first of these was the 1853 piece The British Rule in India. In this article, Marx expresses sympathy with the victims of British colonialism in India, while at the same time seeing British imperialism as essentially progressive, claiming that

“English interference, having placed the spinner in Lancashire and the weaver in Bengal, or sweeping away both Hindu spinner and weaver, dissolved these semi-barbarian, semi-civilized communities, by blowing up their economical basis, and thus produced the greatest, to speak the truth the only social revolution ever heard of in Asia.”2

Marx suggests that through its colonial process, the British are essentially bringing a stagnant and backward society into history, and only through its interference and disruption of this social formation can India become a real actor on the world stage of history. However, this one-sided view would not remain consistent in Marx himself. The conclusion to his 1853 series of articles on India, The Future Results of British Rule in India, would argue for a social revolution in Britain to challenge colonial policy and also point to the possibility of a movement for national independence from British rule. He would also condemn the “profound hypocrisy and inherent barbarism of bourgeois civilization” which “lies unveiled before our eyes, turning from its home, where it assumes respectable forms, to the colonies, where it goes naked.”3

Marx’s ambiguity here can be seen as a result of what the scholar Erica Benner calls a “two-pronged assault on the conflicting reactions of British MP’s to the government-sponsored annexation of ‘native’ Indian states.”4 On one side of this conflict were reformers who denounced the colonization as a crime pure and simple, while on the other end were those who saw colonialism as a historical necessity. For Marx, the former were ineffectual moralists while the latter simply apologists for bourgeois rule under the guise of patriotism. Marx sought to stake out a position between these two camps. To simply morally condemn colonialism seemed to suggest a return to a mythic pre-contact golden age, while to affirm the right of the Empire to annex India would be justifying naked bourgeois interests. By seeking out a position beyond this binary Marx sought to develop a position that would be able to reap the “benefits” of colonization while still looking beyond it.

In the latter years of the 1850’s Marx’s views on colonialism would develop remarkably in contrast to his earlier views. In his 1857-59 series of articles on China and the Second Opium War, any lauding of the progressive effects of colonialism in China is absent. Rather, Marx would focus on heavily condemning French and British colonialism, going so far as to gleefully report the British and French taking 500 casualties and mocking British editorialists who proclaimed their superiority to the Chinese. Marx would also espouse a more anti-colonialist position in his articles on the Indian Revolt of 1857-58, and in a letter to Engels in January, 1858 would tell his close intellectual and political partner that “India is now our best ally.”5

In the course of the 1850s, Marx would move from viewing colonialism as progressive to supporting anti-colonial uprisings. He would likewise support independence for Ireland from Great Britain and Poland from the Russian Empire, agitating for these positions within the First International and the British labor movement. Marx and Engels both would take the position that British workers must support the national liberation of Ireland in order to fight against anti-Irish chauvinism in the labor movement. This was a development from an earlier position that Ireland’s liberation would come through incorporation into a socialist multinational Britain.6 Rather than seeing the separation of Ireland as impossible, it was now inevitable if the unity of the labor movement was to be reached. Only after the separation of Ireland from the British Empire could a multinational socialist state be formed. The merging of nations into a socialist republic would have to occur on the terms of the Irish, not the British:

The first condition for emancipation here – the overthrow of the British landed oligarchy – remains an impossibility, because its bastion here cannot here be stormed so long as it holds its strongly entrenched outpost in Ireland. But once affairs are in the hands of the Irish people itself, once it is made its own legislator and ruler, once it becomes autonomous, the abolition there of the landed aristocracy (to a large extent the persons as the English landlords) will be infinitely easier than here, because in Ireland it is not merely a simple economic question but at the same time a national question, for the landlords there are not, like those in England, the traditional dignitaries and representatives of the nation but its morally hated oppressors.7

From this one can see the development of the Leninist position of the right of nations to self-determination. This position was able to condemn colonialism forthright, without resorting to a moralistic fetishization of traditional pre-colonial society. Marx linked the liberation of the working class in the metropole with the national liberation of the colony, creating a vision of revolution that put agency in the hands of colonized rather than resigning them to passive objects to be liberated by the working class of the more advanced nations. Engels would continue this thesis after the death of Marx in regards to India and other colonies, stating that the proletariat in the metropole could “force no blessings of any kind upon any foreign nation without undermining its own victory by so doing.” Socialism could not be brought to colonized people through imperialist bayonets; instead the colonies were to be “led as rapidly as possible to independence.”8

From this evidence it is clear that Marx (and Engels) began with a more ambiguous and even positive view of colonialism, and moved to a more critical view, developing the beginnings of an anti-colonial Marxism. Yet these anti-colonial positions were mostly found in fragments throughout letters rather than systematized in popular agitational material. As a result, when developing a politics based on the views of Marx, his followers could selectively pick out specific passages from his works to bolster positions that were apologetic of colonialism. While we should be critical of such a scholastic approach to politics, there can be no doubt that many of the Marxists of the Second International justified their positions on readings of Marx.

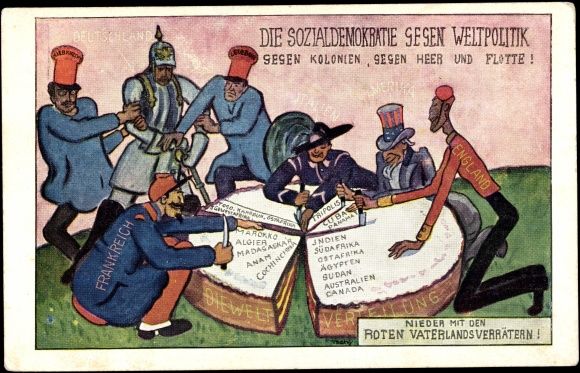

Bernstein vs. Bax on Colonialism

In 1889 the foundation of the Second International saw the beginning of an era of Marxism without Marx, and in 1895 without Engels. The wisdom of the founders would soon no longer be a guiding light for the movement, and a new generation of intellectuals would have to carry the torch. The work of Marx and Engels, while providing a theoretical framework for questions like colonialism and imperialism, hardly provided a full, all-encompassing answer to properly deal with these questions. A single party line that could be applied wasn’t developed. It would be up to debate and deliberation within the union to determine the correct way forward.

In 1896, a year after the death of Engels, the debate would flare up, the two most prominent voices in the dispute being the German Eduard Bernstein and the British Belfort Bax. These debates were triggered by rising tensions between Armenians and the Sultan’s regime in Turkey, with Germany poised to intervene in the Armenians’ favor. In his 1896 article German Social Democracy and the Turkish Troubles, Bernstein would argue strongly in favor of supporting the Armenians, using the rhetoric of more “advanced” nations having a historic duty to “civilize savages”. His arguments would be hard to distinguish from the rhetoric of the colonialists themselves, claiming:

Africa harbors tribes who claim the right to trade in slaves and who can be prevented from doing so only by the civilized nations of Europe. Their revolts against the latter do not engage our sympathy and will in certain circumstances evoke our active opposition. The same applies to those barbaric and semi barbaric races who make a regular living invading neighboring agricultural peoples, by stealing cattle, ect. Races who are hostile or incapable of civilization cannot claim our sympathy when they revolt against civilization.9

Bernstein would of course aim to give his blatant colonial apologism a humanitarian aspect, adding, “We will condemn and oppose certain methods of subjugating savages.”10 Yet in the end Bernstein upheld that colonialism was progressive and should be supported, that it was part of a historical process in which backwards societies would be brought into civilization. He therefore argues for German support in the cause of the Armenians against Turkey using this line of thought.

Belfort Bax, an SDF11 theorist who, like Bernstein, was also controversial, would respond to Bernstein with the harshly titled Our German Fabian Convert: or Socialism According to Bernstein. Beginning his response by accusing Bernstein of ‘philistinism’, Bax would go on to attack Bernstein’s arguments on three fronts. The first was that socialism was not the equivalent to what the bourgeois colonialists called civilization but rather its negation, that the “civilization” imposed on colonized populations was nothing of the type socialists should support.

In his second point, Bax would argue that while it was correct that capitalism was a precondition for socialism, it was not necessary for capitalism to be spread to every single corner of the earth:

“The existing European races and their offshoots without spreading themselves beyond their present seats, are quite adequate to effect Social Revolution, meanwhile leaving savage and barbaric communities to work out their own social salvation in their own way. The absorption of such communities into the socialistic world-order would then only be a question of time.”12

This would tie into the third part of Bax’s rebuttal of Bernstein, which was that rather than spreading capitalism to create the preconditions of socialism, colonialism actually gave capitalism a longer lease on life. Capitalist overproduction, an expression of its own internal contradictions, was the motor force behind the drive for capitalist nations to compete for colonial territories and engage in colonial conquests. By opening up new markets for commodities and cheap labor, capitalism would “soften” its internal crisis tendencies, hence delaying the “final crisis” that would allow for its revolutionary destruction. Hence Bax would make the direct opposite argument as Bernstein: rather than supporting colonial ventures, albeit in a “humane” manner, Social Democracy should support all resistance movements against colonialism regardless of how reactionary they may be, as their victory would increase the internal contradictions of capitalism and speed up its demise.

Bernstein’s next response to Bax, Amongst the Philistines: A Rejoinder to Belfort Bax, would primarily repeat his prior arguments: that “savage races” deserve no sympathy from socialists despite the need for condemning the most brutal forms of colonial subjugation. What exact methods of subjugation were acceptable and which weren’t isn’t clarified by Bernstein, the only clear part of this argument being that subjugation was necessary. This time Bernstein would also make references to the works of Marx and Engels, claiming that Bax was an idealist who was ignorant of what their own positions would have been on this matter. This reveals how the contradictory positions on colonialism in the writings of Marx would leave these issues up to open debate.13

The next round of debates between Bax and Bernstein would resume in late 1897, with Bax’s Colonial Policy and Chauvinism. The arguments in this piece show a development in thought in response to the positions of Bernstein, which Bernstein presented as authentically Marxist due to his upholding of capitalism as a progressive force based on free-labor spread through colonialism. Responding to this notion, Bax would argue that the labor regimes in the colonized nations were not in fact progressive regimes based on “free” waged labor, but a system which “combines all the evils of both systems, modern wage-labor and caste-slavery, without possessing the decisive advantage of the latter.”14 He would also claim that the chauvinism associated with the Anglo-Saxon domination which came with colonialism would be an obstacle to a future brotherhood of humanity, by bringing about a world culture dominated by a single ethnic group. This point would be buttressed with a claim that his stance was not merely a moral one based on abstract notions of human rights, but rather one which was based on a concrete strategy to overthrow capitalism.15 Also of importance is to note that Bax would also draw from the writings of Marx and Engels to make these arguments, countering the use of their arguments by Bernstein.

Bernstein would respond to these arguments with a two-part article, The Struggle of Social Democracy and the Social Revolution. Here he accuses Bax of seeing no deprivations and oppression where capitalism doesn’t exist, essentially holding onto a romantic view of non-capitalist societies. Countering Bax’s argument that the labor regimes introduced in the colonies aren’t progressive and actually based on free labor, Bernstein makes the argument that these initially harsh and un-democratic regimes will naturally evolve into democratic ones as if this tendency is inscribed into capitalism itself. Regardless of the cost, for Bernstein “the savages are better off under European rule.”16

With regards to Bax’s concerns about Anglo-Saxon cultural dominance, Bernstein simply argues that this is countered by France and Germany stepping up to join in as competitors in colonialism. Even if this wasn’t the case, Bernstein sees the cultures victim to colonialism as having no national life of their own, hence being better off assimilated. Not only is this argument obviously chauvinistic in acting as if only Europeans have an authentic culture, but it acts as if the same critique that Bax makes wouldn’t also apply to European dominance and not just Anglo-Saxon dominance.17

Also key to Bernstein’s reply to Bax is his rebuttal of the claim that opposing colonialism will hasten the “final crisis” of capitalism. Bernstein argues against the idea that capitalism will collapse due to its internal crisis tendencies, and argues instead for gradually reforming capitalism to transform it into socialism. It was through this argument that Bernstein would find himself in a political camp that completely diverged from the revolutionary Marxism of the SPD majority, his camp in the party being labelled as “revisionists”.18 Bernstein began from a position of defending colonialism on orthodox Marxist grounds, only to find himself exiting orthodox Marxism in the process.

Karl Kautsky on Colonialism

Karl Kautsky, possibly the most well-respected intellectual voice in the Second International, would initially side with Bernstein in the debate, calling Bax an idealist.19 Yet as the debate progressed Kautsky’s views on colonialism would develop so as to lean more in the direction of Bax’s position in its political conclusion, and point official SPD policy in a more anti-colonial direction. By the time of the 1898 Stuttgart Conference, Kautsky would openly condemn Bernstein’s views. Despite his condemnation of Bernstein, a closer look at Kautsky’s writings on the topic of colonialism reveal a degree of moral ambiguity.

In his 1898 article Past and Recent Colonial Policy, Kautsky lays out his basic framework for understanding colonialism. His argument rests on two basic claims. The first is that industrial capitalists do not have a material interest in colonialism, and instead favor a policy of free trade referred to as Manchesterism. For Kautsky, Manchesterism is not only based on laissez-faire economic policy but also “preaches peace”.20 To the extent that industrial capitalists are interested in colonialism, it is for export markets, which do not always align with colonial policies. Following this claim, Kautsky makes the argument that the class basis for colonialism is basically pre-capitalist aristocratic elites who form the military/colonial bureaucracy and finance/commercial capital. Colonialism is not a policy of the historically progressive industrial capitalist, but a reactionary and backwards policy based on the interests of classes antagonistic to industrial capital. In Kautsky’s analysis:

“the same industrial capitalist, who at home will resist any worker protection law without any qualms, and have no compunction about whipping women and children in his bagnio, becomes a philanthropist in the colonies – an energetic foe of the slave trade and slavery.”21

To explain Germany’s rising interest in imperialism, Kautsky claims that it is to maintain competition with the French and British, whose colonialism is fueled by the pre-capitalist elites and financial capitalists. This argument essentially turns Bernstein’s on its head, countering that colonialism is not a product of capitalism’s progressive tendencies but rather a holdover of reactionary classes. However we can find inconsistent aspects of this argument. For example, he ascribes to settler colonies “based on work” a progressive quality in contrast to colonies based on pure rent extraction. This not only confuses his own argument but reveals moral blindness to the genocidal nature of settler colonialism.22 In 1883 Kautsky would make a similar argument, counterposing the “progressive” and “democratic” colonialism of the USA and England to that of Germany.23 This is in sharp contrast to the arguments made by Bax, which while not purely based on appeals to morality, are strongly based in a moral condemnation of all colonialism. This attitude toward settler-colonialism is also apparent in his 1899 article The War in South Africa, which simultaneously argues for supporting the Boers against the British Empire and asserts, “We, by contrast, condemn modern colonial policy everywhere.”24

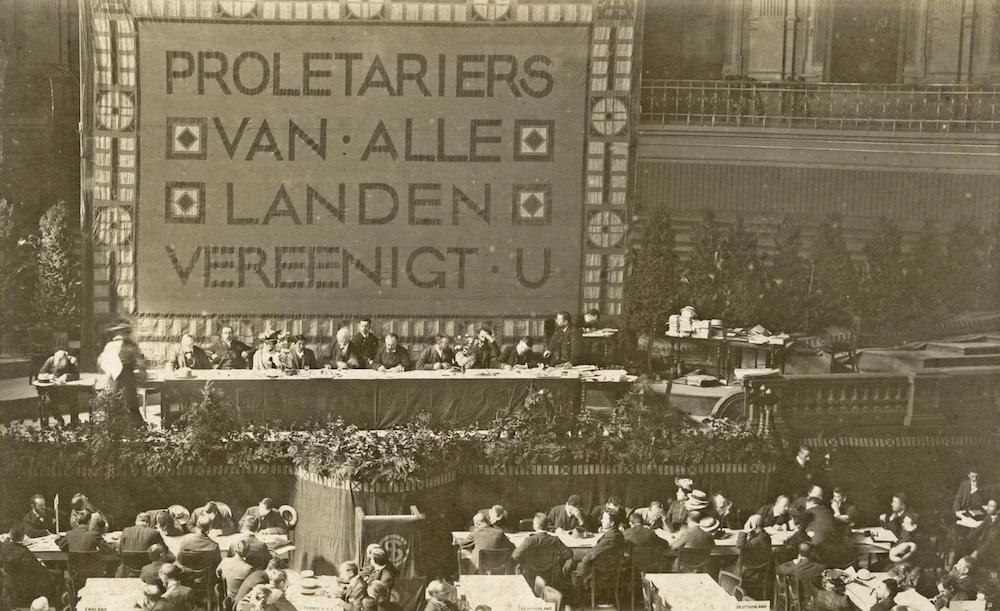

Official Resolutions

The SPD conference in Mainz on September 17-21, 1900 would see the party take up an official resolution on imperialism. Rosa Luxemburg would emerge as a powerful anti-colonial voice, condemning the war against China while urging for active anti-war agitation. The mood of the conference was overall anti-imperialist, with delegates condemning Germany’s intervention in the war against China. Contrary to the views of Bernstein, the resolution passed would state that military conquest was an all-out reactionary policy:

“Social Democracy, as the enemy of any oppression and exploitation of men by men, protests most emphatically against the policy of robbery and conquest. It demands that the desirable and necessary cultural and commercial relations between all peoples of the earth be carried out in such a way that the rights, freedoms and independence of these peoples be respected and protected, and that they be won over for the tasks of modern culture and civilization only by means of education and example. The methods employed at present by the bourgeoisie and the military rulers of all nations are a bloody mockery of culture and civilization.”25

Ultimately it would be the positions more aligned with those of Kautsky and Bax that would win out as the official policy of the SPD. Bernstein would represent a pro-colonialist minority in the party, with some members of the International like Henriette Roland Holst claiming that the mere existence of this minority in the party shouldn’t be tolerated. Days after the Mainz conference the entire International would have a conference in Paris and a similar resolution would be passed, this time with Luxemburg authoring a resolution that not only condemned imperialism but described it as a necessary consequence of capitalism’s newest contradictions.26

The SPD’s Dresden Congress in 1903 and the Sixth International Congress in 1904 would further affirm an anti-imperialist stance. Yet while international congresses were of symbolic importance to the Social Democratic movement (seen as “international workers’ parliaments”), one must take into account the federal structure of the party. Each national party was ultimately autonomous in its decision-making authority, being left to itself to make its own programs and tactical decisions. The congresses were taken seriously by parties but ultimately no central body had the authority to enforce their decisions until the International Socialist Bureau (ISB) was formed at the Paris conference in 1900. Even then, the actual authority of the ISB was ill-defined, and the tendency towards autonomy prevailed. This would mean that parties in the International primarily saw themselves as national parties who served workers on a national basis rather than sections of a single world party.27 The extent to which resolutions would actually be binding on parties was therefore very ambiguous.

Stuttgart Congress

In 1907 the SPD would face a disappointing loss in the electoral campaign known as the Hottentot elections. The Hottentot elections occurred in the context of a pro-colonial nationalist fervor caused by the German colonial war and genocide in South-West Africa, where approximately 65,000 Hereros were massacred in the period from 1904-1908. While the number of eligible voters to the Reichstag election had risen significantly (76.1% in 1903 to 84.7% in 1907), the SPD would lose almost half of its delegates in the Reichstag (81 seats to 43 seats).28 Expecting that more eligible voters would mean more electoral success, the results of this defeat would throw the SPD into a period of doubt and reignite debates over colonial policy.

According to Carl E. Schorske the districts the SPD had maintained in the elections were primarily the working class dominated ones. The section of the electorate lost was the salaried professionals and small shopkeepers, who had fallen prey to the nationalist fervor of the German campaign in South-West Africa. According to Kautsky, the bourgeoisie had promoted the future colonial state as a more attractive alternative to socialism for these strata, something Social Democracy had greatly underestimated. The right wing of the party would respond by asserting that excessive radicalism had cost them votes; the more left-wing elements would point to the Hottentot election as proving the unreliable nature of this “petty-bourgeois” stratum. The radicals in the party therefore saw this as a reason to increase attacks on nationalism and colonial policy while the rightists saw it as a reason to push for a softer stance on colonial policy.29

Alexander Parvus, belonging to the left-wing of the party, would write an in-depth study of the colonial question in response to the Hottentot failure, Colonies and Capitalism in Twentieth Century. Unlike Kautsky’s 1898 pamphlet, Parvus would place colonialism in the context of the contradictions of the modern capitalist system, with overproduction, the falling rate of profit and the merging of production and exchange in finance capital as the motor force behind colonial policies, rather than pre-capitalist elites.30 He cited the increasing imperialist policies of the British Empire as symptoms of its decline as a hegemonic world power, scrambling to hold onto supremacy as it collapses.31 From this theoretical study, Parvus came to the conclusion that colonial policies are symptoms of the decline of capitalism that will present the proletariat with an opportunity for revolutionary action. No political support for colonial policy of any kind was acceptable in Parvus’ view.32

Following the Hottentot failure was the Stuttgart Conference of 1907. This conference would see the colonialism debates resume, this time with a victory for the right. The conclusions made by Parvus, that colonialism was a symptom of capitalist crisis that must be combated with revolutionary action, would be rejected by the majority of conference delegates. In a shift to the right, Luxemburg’s anti-imperialist resolution from the 1900 congress would be dropped and replaced through a process of contentious debate.

One of these debates was between two delegates of the German party, Eduard David and George Ledebour. David quotes August Bebel, a highly respected leader of the party, as saying “it makes a big difference how colonial policy is conducted. If representatives of civilized countries come as liberators to the alien peoples in order to bring them the benefits of culture and civilization, then we as Social Democrats will be the first to support such colonizing as a civilizing mission.”33 The fact this quote is from August Bebel, one of the most important leaders of the Social Democratic movement, is revealing. It shows that for many Social Democrats, opposition to colonialism wasn’t opposition to European supremacy and was still premised on the legitimacy of a European civilizing mission. It was merely the methods of colonialism that were opposed, methods that were to be replaced by peaceful ones that would make Europeans welcome missionaries of progress.

Ledebour would respond by polemicizing against Bebel as well as David, arguing that Bebel’s position asserted the possibility that colonial policy could be anything other than the existing horror and inhumanity that it was. Rather than calling for a more “humane” colonialism, he says that only the resistance of the exploited can lessen the brutalities of colonialism. After Ledebour spoke, a delegate from Belgium, Modeste Terwagne, would argue that if the occupation of the Congo were ended that “industry would be seriously damaged” and that “men utilize all the riches of globe, wherever they may be situated.”34

Ledebour and a Dutch Socialist, Hendrick van Kol, would draft a resolution in compromise with the socialist colonizers who condemned existing colonial policy while neglecting to condemn colonial policy under capitalism in general. Terwagne would introduce an amendment that affirmed the potential for a socialist colonial policy that acted as a civilizing force, while David would add another amendment saying that “the congress regards the colonial idea as such as an integral part of the socialist movement’s universal goals for civilization.”35 David’s amendments was rejected and Terwagne’s was incorporated in the final draft which was accepted by a majority of the congress:

“Socialism strives to develop the productive forces of the entire globe and to lead all peoples to the highest form of civilization. The congress therefore does not reject in principle every colonial policy. Under a socialist regime, colonization could be a force for civilization.”36

While the resolution also contained commitments for parliamentary delegates to “fight against merciless exploitation and bondage” and “advocate reforms to improve the lot of the native peoples” it failed to reject colonialism as such and instead aimed to reform the existing colonial occupations. This turn to the right disgusted Luxemburg, Parvus and Kautsky. However, the turn towards what was essentially a pro-colonial stance was a product of democratic deliberation, a process that could be reversed through open debate. By the end of the conference, Kautsky was able to build up a bloc of support that would defeat the original resolution by a vote of 128 against 108, with 10 abstentions. Replacing the original resolution would be a resolution that would state that the congress “condemns the barbaric methods of capitalist colonization” and claim “the civilizing mission that capitalist society claims to serve is no more than a veil for its lust for conquest and exploitation.”37

While an anti-imperialist motion did pass, 128 against 108 was hardly a vast majority of delegates. Russian Social Democrat Vladimir Lenin believed this to be a sign of growing opportunism within Social Democracy, one that needed to be battled against with vigilance. The Stuttgart conference “strikingly showed up socialist opportunism, which succumbs to bourgeois blandishments” and “revealed a negative feature in the European labour movement, one that can do no little harm to the proletarian cause, and for that reason should receive serious attention.”38 Social Democracy was not guaranteed to stick to a strict anti-imperialist platform, and such a stance would have to be battled for in the halls of congresses and in theoretical debates.

Debates on colonialism and imperialism would continue in Social Democracy, reaching an apogee when a majority of SPD Reichstag delegates would vote for war credits at the beginning of World War One, followed by the majority of other Second International parties. Ultimately Lenin’s fear of growing opportunism was proven correct. However, while one could assume that the Social Democrats who voiced opposition to colonialism most consistently would be those who vigorously opposed the war, anti-colonialists like Parvus and Belfort Bax would find themselves amongst the ‘social-patriots’ who rallied behind the war. Arguments for supporting the war would vary. In the case of Parvus it was his conclusion that it was necessary to defend the progressive German state against reactionary Czarism that led him to rally behind the Kaiser.39 If support or rejection of WWI was the ‘final test’ for Social Democrats, positions in the debates over colonialism ultimately would not serve as predictors for who would pass.

Conclusion

It would take the October Revolution, with its radical approach to the national question and solidarity with the struggles of colonial peoples, to truly establish an anti-colonial and anti-imperialist orthodoxy in Marxism. Lenin’s anti-colonial Marxism would inspire national liberation leaders in the colonies like Ho Chi Minh to align with the International Communist movement and deal a blow to Marxist Eurocentrism. While a blow was dealt, it wasn’t quite fatal, as European chauvinism would still haunt Marxist parties throughout the 20th Century, the most famous example being the French Communist Party’s refusal to support Algerian independence at the most crucial moment. In these instances, Euro-chauvinists were continuing an unfortunate tradition within Marxism that contested for legitimacy in the Second International using the writings of Marx himself.

The pro-colonial positions found both in Marx and in the Second International have a common theoretical basis that can be identified as Eurocentrism. According to Samir Amin, a key theoretical backdrop to the ideology of Eurocentrism is economism, defined as the view that “economic laws are considered as objective laws imposing themselves on society as forces of nature, or, in other words, as forces outside of the social relationships peculiar to capitalism.”40 Eurocentric economism reifies economic development as an inevitable process that occurs as long as “cultural” factors don’t stand in the way. It sees the uneven development of the world and the backwardness of the periphery as a product of the specific cultures of these societies being inferior to that of Europeans, barriers to economic progress that must be broken down. In contrast, the scientific socialist view sees economic development as a process contested by class struggle and the role of imperialism in reproducing the core/periphery division

In the Eurocentric ideology, the European world is seen as a world of wealth due to its unique culture while the rest of the world is held back by its culture (Asiatic stagnation for example) and only progresses to the extent it copies Europe. History is a progressive march towards modernization, and “it becomes impossible to contemplate any other future for the world other than its progressive Europeanization.”41 The future is shaped and defined by the West, which has everything to teach the rest of the world and nothing to learn from it. As a result, Western capitalism stands as a model for the planet, its mode of development universal for all countries and only held back by internal backwardness when this development fails to take hold. This chauvinist ideology took hold over Bernstein and even Marx at times, seeing the spread of colonialism as a progressive process that would enforce the development of stagnant societies.

According to the ideology of developmental economism, if not for the backwardness of the non-European world the development of capitalism would ultimately homogenize the world. Four-hundred years of global capitalist development has shown the world still heavily divided, not only between bourgeois and proletariat but between core and periphery nations. Capitalism is dominant in almost every country today, and the uneven development of the world still haunts the periphery. Bernstein’s vision of colonialism bringing capitalist “civilization” to the world has come to pass. Yet imperialism still ravages the world, creating what John Smith calls the super-exploitation of the global south by the developed capitalist nations. Capitalism has spread worldwide, but it has formed a global division of labor where the post-colonial proletariat labors for starvation wages to produce super-profits realized in the imperialist countries. According to Smith,

“…the very processes that produced modern, developed, prosperous capitalism in Europe and North America also produced backwardness, underdevelopment, and poverty in the Global South…the accelerated spread of capitalist social relations among Southern nations has been far more effective in dissolving traditional economies and ties to the land than in absorbing into wage labor those made destitute by the process.”42

The historical verdict seems to have been made in favor of the arguments of Bax and the anti-imperialists rather than Bernstein. Yet we must not pretend that this debate is merely of historical importance. Today we face an imperialism more based in systematically enforced economic underdevelopment, which is maintained through imperialist police actions. Rather than direct colonialism, it is primarily economic imperialism of the more informal kind that devastates the world. As a result, the defenders of imperialism amongst the left come in different forms than the likes of Bernstein. They are not the colonial apologists of old but advocates of US intervention as progressive in certain situations or those who refuse to be critical of social democrats who vote for imperialist war budgets. There are also those who refuse to take up demands for the deconstruction of settler-colonial states, like the United States, and the national liberation of those still under settler-colonial occupation, in the name of focusing on bread-and-butter demands. As the socialist movement develops, we must learn from the failures of the Second International to clearly establish an anti-colonial and anti-imperialist position in its ranks, which exists not only on paper but in the class awareness of the rank and file.

The Practical Policy of Revolutionary Defeatism

Matthew Strupp lays out the politics of revolutionary defeatism in contrast to the approaches of third-campism and third-worldism.

In April 1964, at a luxury hotel overlooking Lake Geneva, a young Jean Ziegler, at that time a communist militant, asked Che Guevara, for whom he was serving as chauffeur, if he could come to the Congo with him as a fighter in the commandante’s upcoming guerilla campaign. Che replied, pointing at the city of Geneva, “Here is the brain of the monster. Your fight is here.”1 Che Guevara, though certainly not a first-world chauvinist, recognized the crucial role communists in the imperialist countries would have to play if the global revolutionary movement were to be successful. How then, as communists in close proximity to the brain of the monster, or in its belly, as Che is reported to have put it on another occasion, can we effectively stand against the interests of “our” imperialist governments? The answer to that question is the policy of revolutionary defeatism. This article will go over the origins and meaning of defeatism, take a look at its complexities with the help of some examples, and take up the challenge posed to it by the politics of both third-worldism and third-campism.

Origins of Defeatism

The logic of revolutionary defeatism flows from the basic Marxist premise that the proletariat is an international class, and that in order to triumph on a global scale it needs to coordinate its political struggle internationally. This means that when workers in one country are faced with actions by “their” state that pose a threat to the working class of another country, they must be loyal to their comrades abroad rather than their masters at home. Rather than be content with simple condemnations, they must also pursue an active policy against their state’s ability to victimize the members of their class in the other country. This means strike actions in strategic industries, dissemination of defeatist propaganda in the armed forces, and organizing enlisted soldiers against their officers. In the case of a particularly unpopular or difficult war, all politics tends to be reoriented around the war question, and, if the state has been destabilized by the demands of the war and the ongoing defeatist activity of the workers’ movement, this can lead to an immediate struggle for power and the possibility of proletarian victory. If no such conditions are present, the defeatist policy can serve to train the proletariat and its political movement to oppose the predatory behavior of its state and, in practical terms, blunt the business-end of imperialism and mitigate its devastating consequences for the working class abroad.

This policy of defeatism developed alongside the growth of mass-working class politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the proletarian movement grew to the point where its international policy became a live and important question. There were many positions bandied about in this period, some more or less defeatist, others placing the workers’ movement squarely behind national defense. Many individual socialists, including Marx and Engels, varied in their advocacy of one or another. An early expression of a policy of revolutionary defeatism can be seen in Engels’ 1875 letter to August Bebel, in which he criticizes the newly drafted Gotha Unification Program of the German Social-Democratic Party (SPD) for downplaying the need for international unity of the workers’ movement. Engels writes:

“…the principle that the workers’ movement is an international one is, to all intents and purposes, utterly denied in respect of the present, and this by men who, for the space of five years and under the most difficult conditions, upheld that principle in the most laudable manner. The German workers’ position in the van of the European movement rests essentially on their genuinely international attitude during the war; no other proletariat would have behaved so well. And now this principle is to be denied by them at a moment when, everywhere abroad, workers are stressing it all the more by reason of the efforts made by governments to suppress every attempt at its practical application in an organisation! And what is left of the internationalism of the workers’ movement? The dim prospect — not even of subsequent co-operation among European workers with a view to their liberation — nay, but of a future ‘international brotherhood of peoples’ — of your Peace League bourgeois ‘United States of Europe’!”2

Engels is congratulating the German workers’ movement for their internationalist behavior in war but chiding them for retreating from this internationalism in their political program. The war he is referring to is the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Marx had actually initially been German defensist in this war but changed his position after German troops went on the offensive.3 The German workers’ movement as a whole, though, mostly opposed the war in an admirable fashion, and Engels claims this was the reason for their esteem in the international movement. Not only did its political leaders condemn the war, but its organizations also carried out strikes in vital war industries in the Rhineland. This active stance of opposition to the war and active coordination of international political activity by the working class is what Engels thought was missing from this part of the Gotha Program, and he thought it was a step down from the truly international perspective of the International Workingmens’ Association. Its drafters included the vague internationalist language of the “Peace League bourgeois”, but made no mention of the practical tasks of the movement in this respect. Engels argued that the workers’ movement needed to coordinate its activities on an international scale, and that included acting in an internationalist fashion during war-time.

Nor did Engels limit his expression of a precursor to revolutionary defeatism to wars within Europe, where there was a developed working-class movement that could be destroyed in another country by an invasion from one’s own. He thought it was also applicable in matters of “colonial policy”, and that workers in imperialist countries had the political task of organized opposition to imperialist exploitation. He believed that if they failed in this task they would become political accomplices of their bourgeoisie. In an 1858 letter to Marx he wrote:

“the English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois, so that the ultimate aim of this most bourgeois of all nations would appear to be the possession, alongside the bourgeoisie, of a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois proletariat. In the case of a nation which exploits the entire world this is, of course, justified to some extent.”4

These writings of Engels’ express two important features of Lenin’s revolutionary defeatist policy in World War I and that of the Communist International after the war. Namely, the importance of active, organized efforts to hamper the ability of one’s own state to carry out the business of war and imperialism, and the applicability of the policy to both inter-imperialist wars and to colonial and semi-colonial/predatory imperialist wars.

The Second Socialist International received the first major test of its ability to pursue a defeatist policy with the onset of World War One– and it failed spectacularly. Up until that point, the German SPD, the model party of the International, had followed an admirable policy of voting down all state budgets of the German Empire in the Reichstag under the slogan “For this system, not one man and not one penny!”, as Wilhelm Liebknecht declared at the foundation of the Bismarckian Reich.5 This policy allowed the German party to think of its parliamentary activity with a lens of radical opposition, through which they saw themselves as infiltrators in the enemy camp, intent on causing as much trouble for the state and its ability to rule as possible and securing whatever measures they could to benefit the movement outside the parliament. They made use of all the procedural stops they had at their disposal along the way, and used their parliamentary immunity to decry abuses like violence against the workers’ movement and German colonial wars in ways that would otherwise be illegal, though this didn’t keep August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknect, for many years the SPD’s two representatives in the Reichstag, from being convicted of treason and imprisoned for two years for their opposition to the Franco-Prussian War, particularly for linking opposition to German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to support for the Paris Commune.6 This was not a revolutionary defeatist policy in itself and the behavior of socialists in relation to the armed forces in wartime remained untheorized, but it was an important attitude for a party of revolutionaries to adopt towards their own state and its warfighting capacity. Politicians the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) has elected in the United States, unfortunately, do not seem to see their activity in the legislature in this way and seem to think they are there more to “get things done” than to “hold things up” for the benefit of the movement. The DSA has also failed to adopt a “not one penny” position on the military budget. A resolution to do so was introduced at the 2019 convention, but was not championed by either of the main factions there.

In August 1914 the SPD’s anti-militarist discipline broke down, as many of its representatives in the Reichstag voted for German war credits and much of the movement fell in line behind the war effort. The same happened in all the other parties of the International in the belligerent countries, with the exception of Russia and Serbia. The divide between those who supported the war and those who opposed it did not follow the existing pre-war political divisions. War socialists were drawn from the right, left, and center of the International. Some made the decision on the basis of “national defense” or out of an unwillingness to become unacceptable to bourgeois politics when they were winning so many reforms for the working class, others to defend French liberty from the Kaiser, or German liberty from the Tsar, still others to defeat British finance capital’s grip on the world, or to spark a revolution, or to train the proletariat in the martial spirit for the waging of the class struggle.7 No matter how they justified it though, these socialists were all feeding the proletariat into the meat grinder of imperialist war. There were no progressive belligerents in the First World War. Categories of “aggressor” and “victim” did not apply. It was, as Lenin put it, an “imperialist war for the division and redivision” of the spoils of global exploitation.8

The immediate reaction of those in the socialist movement opposed to the war after the capitulation of so many of the national parties was to organize a series of conferences at Zimmerwald (1915), Kienthal (1916), and Stockholm (1917), to work out a socialist peace policy. At Zimmerwald there soon emerged a left, who favored a policy of class struggle against the war, essentially a revolutionary defeatist position, since carrying it out would detract from the coherence and fighting ability of the armed forces. Lenin sided with this left but said they hadn’t gone far enough, not only did a policy of class struggle against the war, or as he put it: revolutionary defeatism, need to be put forward, but socialists loyal to the international proletariat had to organize themselves separately in order to be able to carry it out.9 This struggle would be a political one, directed at the armed forces of the capitalist state and aiming for their breakup under the pressure of defeatist propaganda and fraternization between the troops of the belligerent countries. On the concrete form of this struggle Lenin wrote, in November of 1914, in The Position and Tasks of the Socialist International:

“War is no chance happening, no “sin” as is thought by Christian priests (who are no whit behind the opportunists in preaching patriotism, humanity and peace), but an inevitable stage of capitalism, just as legitimate a form of the capitalist way of life as peace is. Present-day war is a people’s war. What follows from this truth is not that we must swim with the “popular” current of chauvinism, but that the class contradictions dividing the nations continue to exist in wartime and manifest themselves in conditions of war. Refusal to serve with the forces, anti-war strikes, etc., are sheer nonsense, the miserable and cowardly dream of an unarmed struggle against the armed bourgeoisie, vain yearning for the destruction of capitalism without a desperate civil war or a series of wars. It is the duty of every socialist to conduct propaganda of the class struggle, in the army as well; work directed towards turning a war of the nations into civil war is the only socialist activity in the era of an imperialist armed conflict of the bourgeoisie of all nations.”10

Lenin did not think that the adoption of a revolutionary defeatist position by communists in the imperialist countries was only applicable to the specific conditions of World War I, where the conflict was reactionary on all sides and the proletariat had well developed political organizations in all the belligerent countries who could turn the struggle against the war into an immediate struggle for power. In response to the objection of the Italian socialist leader Serrati to a resolution proposed by the Zimmerwald left that advocated a class struggle against the war, that such a resolution would be moot because the war was likely to end quickly, Lenin said: “I do not agree with Serrati that the resolution will appear either too early or too late. After this war, other, mainly colonial, wars will be waged. Unless the proletariat turns off the social-imperialist way, proletarian solidarity will be completely destroyed; that is why we must determine common tactics.”11 Here, the revolutionary defeatist policy is not simply a path to the immediate struggle for power, as it indeed was in the case of WWI, rather it’s related to the adoption of a particular attitude to the activities of one’s own state in general. For communists in the imperialist countries, this means fighting against the wars your country wages to maintain its grip over its colonies and semi-colonies, using the same tactics you would use in the case of a “dual defeatism” scenario, where communists in all the belligerent countries are defeatist in relation to their country’s war effort, in an inter-imperialist war that is reactionary on all sides.

However, these two scenarios should not be confused. Although Lenin claimed the policy pursued in response to one should be put forward in the case of the other, this should not be extended to the communists in the oppressed country. There is no question of being “defeatist” in relation to a progressive war for national liberation. The Communist International made this clear in condition 8 of its 21 conditions for affiliation:

“Parties in countries whose bourgeoisie possess colonies and oppress other nations must pursue a most well-defined and clear-cut policy in respect of colonies and oppressed nations. Any party wishing to join the Third International must ruthlessly expose the colonial machinations of the imperialists of its “own” country, must support—in deed, not merely in word—every colonial liberation movement, demand the expulsion of its compatriot imperialists from the colonies, inculcate in the hearts of the workers of its own country an attitude of true brotherhood with the working population of the colonies and the oppressed nations, and conduct systematic agitation among the armed forces against all oppression of the colonial peoples.”12

The important point here is that revolutionary defeatism in a predatory imperialist war is only a prescription for communists and proletarian movements in the imperialist countries. Today this means those that benefit from a flow of value coming from global wage arbitrage and the super-exploitation of newly proletarianized former peasants in the former colonial and semi-colonial world. In such a war, the question of defeatism or defensism in the oppressed countries, in the realm of practical policy, is precisely a question for communists in the oppressed countries themselves. This question should be decided on the basis of how best to serve the ends of national liberation and social revolution, taking the particular national political conditions and those of the war into account, but the victory of the oppressed country should be favored over that of the imperialist country.

The Communist International itself may actually have gone too far in the direction of defensism, not in the sense of favoring the victory of the oppressed country, which should always be the case, but in the sense of the relationship of communists in the oppressed countries to their state and to other political forces. Its policy of the anti-imperialist united front was ambiguously formulated and its implementation often involved subordinating the communist parties to the bourgeois nationalist movements. The most notorious example being the case of China, where Comintern directives on the Communist Party’s relationship to the Kuomintang had to be explicitly rejected by Mao and his co-thinkers for the Chinese Revolution to triumph.13 This logic has been taken to the extreme in recent years by the Spartacist League, a far-left sect that has devoted space in their paper to putting forward a position of military support for ISIS: “We take a military side with ISIS when it targets the imperialists and forces acting as their proxies, including the Baghdad government and the Shi’ite militias as well as the Kurdish pesh merga forces in Northern Iraq and the Syrian Kurdish nationalists.”14 The cases of China and modern Iraq and Syria show that sometimes in cases of internal disorder or when the forces “resisting the imperialists” are particularly reactionary, whether the Kuomintang or ISIS, the best option for communists and the anti-imperialist struggle is for communists in the oppressed country to wage a military struggle against both the imperialists and the reactionary forces “resisting” them.

Vietnam

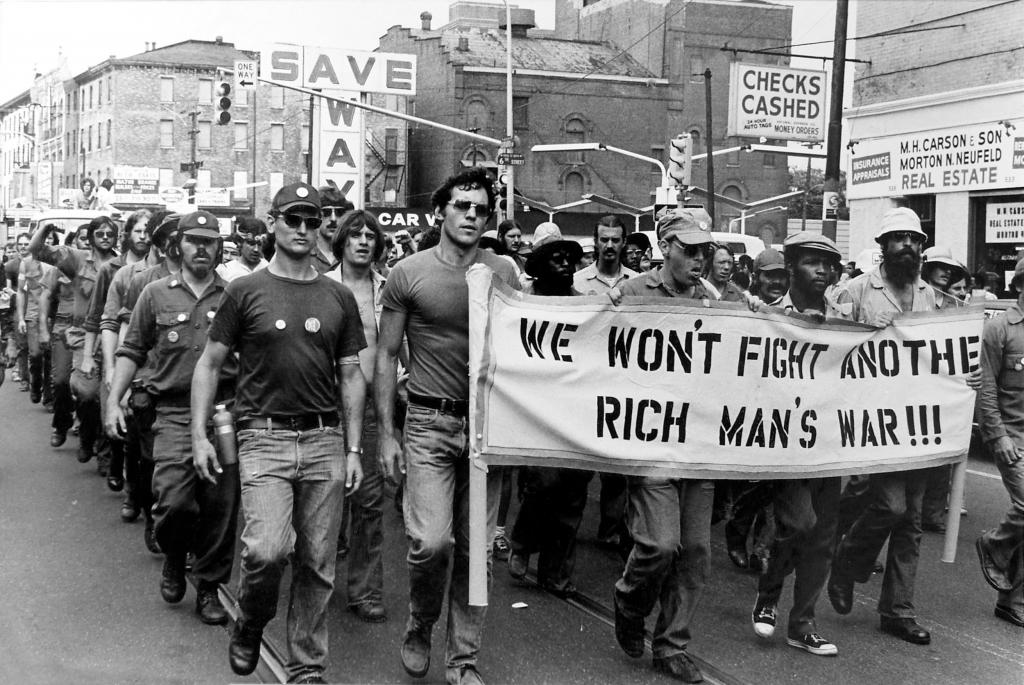

The most successful application of revolutionary defeatist tactics in the US was in the case of the Vietnam war. The best-known images of the anti-war movement in the US are of large public marches and of police repression on college campuses. The truth is that these things were actually pretty ineffective at producing a US defeat and withdrawal. Large demonstrations can do something to turn public opinion against the war and college students were able to take some actions that made a meaningful difference by taking advantage of their positions in a crucial part of the war machine: the university; but these things were not enough to halt the functioning of the most destructive imperialist military in history. We can verify this by comparing the movement against the war in Vietnam with that against the war in Iraq. As with Vietnam, the Iraq war was opposed by millions of demonstrators, including by between 6 and 11 million people on a single day, February 15, 2003, the largest single-day protest in world history; yet the war kept going.15

What was the difference in Vietnam? The answer lies both in the brilliant military strategy of the Vietnamese liberation movement under the leadership of the Communist Party, and in the practical application of a revolutionary defeatist policy by sections of the US far-left and workers’ movement. This meant disrupting the recruitment of the US armed forces, and especially, organizing opposition within the military itself. This resulted in a situation where “search-and-evade” tactics became the ordinary state of affairs for many units, as common soldiers deliberately avoided combat or simulated the appearance and sounds of combat to deceive their officers, over 600 soldiers carried out “fraggings”, murders or attempted murders of their officers, often with frag grenades, and groups of soldiers occasionally carried out organized mutinies. By June 1971 this state of widespread organized resistance to the war led military historian Colonel Robert D. Heinl to write an article titled The Collapse of the Armed Forces, in which he claimed that “The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States.”16 This was undeniably a key factor in the breakdown of US warfighting ability in Vietnam and the eventual US withdrawal.

Some insist that the example of war resisters in the US military during the occupation of Vietnam, and by extension, the entire premise of a policy of active revolutionary defeatism, is entirely useless to today’s revolutionary movement because the nature of the US military has been entirely transformed by the transition to an all-volunteer force in the late-70’s and 80’s. What this position misses is the extent to which the claim that the US military is an all-volunteer force is itself an ideological artifice crafted by the US military establishment and the degree to which poverty itself still acts as a draft. The US military does not make public information on the income-levels or class positions of the families from which it recruits, only their geographic distribution. The fact that the localities that enlistees are drawn from are more affluent than average does not rule out that the enlistees themselves may be poor. The higher cost of living in these areas may in fact be an additional stimulus to enlistment, and the fact that military recruiters regularly use material incentives, like the promise of a free education, to prey on working-class kids, is no secret. This means that the class divide in the armed forces has not entirely been eliminated, that officers’ interests still conflict with those of enlistees, and that the possibility of mass war resistance from within the ranks of the armed forces, especially as part of a coordinated working-class struggle against imperialist war, still lies within reach.

Iran and Third-Campism

With the assassination at the beginning of this year of high ranking Iranian general Qassim Soleimani at the hands of the United States, the prospect of war with Iran became a very real possibility. In fact, a section of the US foreign policy establishment has been hellbent on bombing or invading Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that established the current Iranian regime, and the US has imposed harsh sanctions on Iran that themselves amount to a form of warfare. These sanctions have no doubt contributed to the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran, which has killed 988 and infected over 16,000, roughly 9 in 10 cases in the Middle East.17 Although the immediate worry about an invasion has died down since January, it’s still important for communists to work out what their response to such an invasion would be, because the threat remains on the table.

The main question is whether a revolutionary defeatist policy in relation to a war with Iran should be pursued or whether a Third-Campist position of “Neither Washington nor Tehran” ought to be put forward. The idea of Third-Campism, in this case, is that the political regimes of the United States and of Iran are both so reactionary that the proletariat has no stake in either side’s victory or defeat in the war and should, therefore, neither support nor actively oppose its prosecution by the imperialists. This approach is flawed. If we were considering a war between two imperialist countries on equal standing, both with reactionary governments, what this leaves out is the benefit that the proletariat in both the belligerent countries could gain by an active pursuit of a revolutionary defeatist policy. Either, it could open up the road to the seizure of power by the proletariat in one or both belligerent countries or it could only serve to train the proletarian movement in each country in the art of carrying out a struggle against “its own” state.

However, in the case of a US attack on Iran, this “soft Third-Campist” position of dual defeatism, like that implied by the left-communist International Communist Current, when it describes the Middle East after the Soleimani assassination as “dominated by [an] imperialist free for all” would also be wrong because it regards both the United States and Iran as imperialist.18 Such a war would not be reactionary and imperialist on both sides, a reactionary war by the US for the reconquest of one of its semi-colonies. It is no coincidence that the US only became hostile to the Iranian government after the ouster of its puppet the Shah, meaning that the Iranian war effort would contain elements of a progressive national liberation struggle. In the case of a US invasion, the main enemy for Iranians is not at home, their main enemy is imperialism. Communists in Iran are, of course, opposed to the political regime of the Islamic Republic for its brutal suppression of the workers’ movement and its political organizations, its regressive stance on women’s rights, and its treatment of national minorities, but they do not think it fights too vigorously against US imperialism.19 Communists in the United States should take the position: “better the defeat of US troops than their victory”, and their task would be to carry out an active policy of revolutionary defeatism against an invasion of Iran. The task of communists in Iran would be to fight off the imperialist invaders by any means necessary, including by opposing any effort by the Iranian government to disarm the Iranian proletariat as it prepares itself to resist an invasion.

Third-Worldism

There is another political strand that downplays the importance of active revolutionary defeatist politics in the imperialist countries: Third-Worldism. In this case, it is not the desirability of the proletariat in the imperialist countries carrying out a revolutionary defeatist policy that is questioned, but its political inclination to do so. All this leaves us with is joystick or sideline politics, the cheering on of great revolutionaries and great revolutionary movements, but always happening somewhere else. This makes Third-Worldism a self-fulfilling prophecy, the denial of the ability of the proletariat in the imperialist countries to challenge the imperialist bourgeoisie which exploits both them (usually rationalized by saying that proletarians in the imperialist countries are equally exploiters) and their comrade workers around the world, becomes a reason not to organize to do so. Of course a fraction of the super-profits of imperialism is sometimes distributed to workers in the imperialist countries with the aim of purchasing their loyalty to the bourgeois state. Our point is to build a movement capable of credibly offering something better than that: communism.

The idea that politics flows directly from the movement of money is an economist error, if it were true, all communist politics would be pointless, because that factor will never be in our favor. Rather, international working-class consciousness will necessarily be a subjective product of common struggle, including the anti-imperialist struggle. It is likely, as Trotsky argues in his History of the Russian Revolution, that for reasons of combined and uneven development, the world revolution will be sparked in the oppressed countries first, but that process will not ultimately be successful if revolution does not come to the imperialist countries as well.20 Most great Third-World revolutionaries have been clear about this, Che certainly was. Indeed, as the late Egyptian communist, Samir Amin wrote in Imperialism and Unequal Development:

“…Third-Worldism is strictly a European phenomenon [we may say a phenomenon of the imperialist countries]. Its proponents seize upon literary expressions, such as ‘the East wind will prevail over the West wind’ or ‘the storm centers,’ to justify the impossibility of struggle for socialism in the West, rather than grasping the fact that the necessary struggle for socialism passes, in the West, also by way of anti-imperialist struggle in Western society itself… But in no case was Third-Worldism a movement of the Third-World or in the Third-World.”21

Third-Worldism began as an optimistic reaction to successful national liberation struggles in the oppressed countries in the mid-20th century, but to the extent that it exists today, it is simply a symptom of our defeat. Third-Worldism may produce amusing artefacts like That Hate Amerikkka Beat, but it offers nothing to the practical struggle for global proletarian revolution because it refuses to even consider what might need to be done to make revolution in the imperialist countries. None of this is to discount the work of communists in the Third-World, who are doing their part in fighting imperialism and their bourgeoisie. The problem with Third-Worldism is that it’s a poor form of solidarity that looks not to the ways in which one can most practically ensure the final triumph of those one is in solidarity with.

The Upcoming Battle

The goal of communists in the imperialist countries should be to create, to quote once again Che Guevara, “two, three… many Vietnams”22, not in the sense Che used it, focoistic guerilla campaigns, but in the sense of successful applications of the revolutionary defeatist policy of class struggle against imperialist war, which killed the US military’s ability to maintain the occupation of that country. This means, in the case of unprogressive war, strikes in war industries, spreading defeatist propaganda in the armed forces, and organizing common soldiers against their officers and the war effort. We must also fight for a truly democratic-republican military policy in peacetime, rejecting foreign intervention by the United States and fighting for the universal arming and military training of the people and the right to freely organize in militias for the proletariat, as well as freedom of speech and association for the ranks of the present-day armed forces. “War is the continuation of politics by other means”23 and now is a time of relative peace, a time for politics, a time to build up our forces, to train them to become a honed weapon of class struggle, and “not to fritter away this daily increasing shock force in vanguard skirmishes.”24 But a time of war is coming, and we must have those “other means” at our disposal, we must be prepared to crush our enemies and to use the destructive and atrocious wars conjured up by the bourgeoisie as opportunities to turn the imperialist war into a civil war, to make war on the ruling class as a road to the seizure of power by the proletariat and the triumph of communism.

Invasion: A Story of Anti-Colonial Resistance

Medway Baker reviews and contextualizes a short documentary on struggles of the Wet’suwet’en against the modern Canadian state.

On February 6, the Canadian state’s police force, the RCMP, invaded Wet’suwet’en territories. On February 10, it arrested their Unist’ot’en matriarchs. It is a brutal reminder of the ongoing invasion by settler-colonial forces of the nation’s lands. This comes shortly after the Wet’suwet’en nation invoked their own laws alongside Canadian law to mandate that Coastal GasLink, which is building a pipeline on Wet’suwet’en territory against the wishes of the Wet’suwet’en people, leave their lands. Coastal GasLink has refused to comply and has called on the capitalist state to uphold its interests.

The RCMP was founded under the name North-West Mounted Police in 1873, as an explicitly colonising force, shortly after the Métis Red River Rebellion led by Louis Riel. Its duty was to protect British-Canadian interests in the vast uncolonised expanses, and extend the colonial boot as settlers flocked to occupy indigenous lands. It subjected indigenous nations to colonial law, a task that it continues to fulfill to this day. Later, the RCMP would be used to crush labour revolts and repress communists. It is fundamentally an instrument of the capitalist, settler-colonial Canadian state. The present use of the RCMP to dispossess and repress the Wet’suwet’en people is one incident among countless assaults carried out by this force.

To learn more about this struggle, I watched a short documentary produced by the Wet’suwet’en to spread the message of their fight for peace and survival. I was deeply moved by the plight of this oppressed people, and it hardened my resolve to fight against capitalism and settler-colonialism.

Invasion begins, aptly, with police harassing a Wet’suwet’en woman. It’s a stark image, this meeting at the bridge marking the entrance to the Unist’ot’en territory. Agents of the settler-colonial Canadian state stand threateningly at the border. Behind the woman there are signs declaring “No to colonial violence” and “Defend the yintah!” There is an undeclared war here. On one side, a people who have lived in this area for countless generations, trying to go about their lives in peace. On the other side, an occupying force which seeks to dispossess the Unist’ot’en in the name of capitalist accumulation. Because the Unist’ot’en find themselves in the way of the capitalists’ exploitative ventures, they are no longer citizens with equal rights; they are the enemy of capital, and they must be destroyed.

The woman in question is Freda Huson, a spokesperson of the Unist’ot’en. She and others have been fighting against a proposed pipeline through their unceded lands for years. At a protest in front of a colonial courthouse, she declares, “Everyone needs to stand up, not just indigenous people. Everyone needs to stand up to the political powers that be.” This is fundamentally an internationalist message, a message that all people, all of the dispossessed, must stand up to defend their rights and their lives from the capitalists and their state.

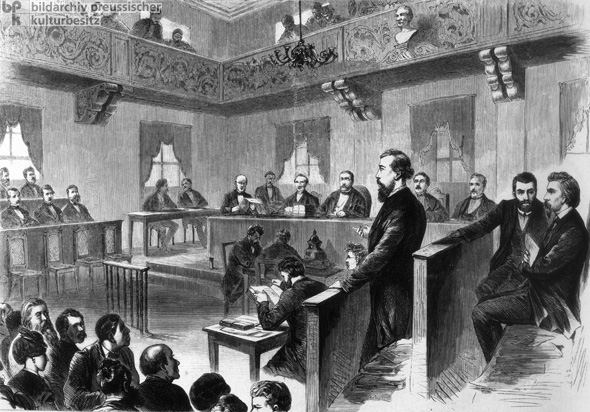

It’s reminiscent of another indigenous freedom fighter’s message, all the way back in 1885. Louis Riel, at the trial where he was sentenced to death for rebelling against British-Canadian colonialism, said,

“When I came into the North West in July, the first of July 1884, I found the Indians suffering. I found the half-breeds [Métis] eating the rotten pork of the Hudson Bay Company and getting sick and weak every day. Although a half-breed, and having no pretension to help the whites, I also paid attention to them. I saw they were deprived of responsible government, I saw that they were deprived of their public liberties. I remembered that half-breed meant white and Indian, and while I paid attention to the suffering Indians and the half-breeds I remembered that the greatest part of my heart and blood was white and I have directed my attention to help the Indians, to help the half-breeds and to help the whites to the best of my ability…. No one can say that the North-West was not suffering last year, particularly the Saskatchewan, for the other parts of the North-West I cannot say so much; but what I have done, and risked, and to which I have exposed myself, rested certainly on the conviction, I had to do, was called upon to do something for my country.

“It is true, gentlemen, I believed for years I had a mission, and when I speak of a mission you will understand me not as trying to play the role of insane before the grand jury so as to have a verdict of acquittal upon that ground. I believe that I have a mission, I believe I had a mission at this very time.”1

Echoing Louis Riel, Huson announces, “I know I’m doing the right thing.”