Cam W responds to the recent debate between Taylor B and Donald Parkinson, outlining a Maoist approach to politics based on the mass line as an alternative to their positions.

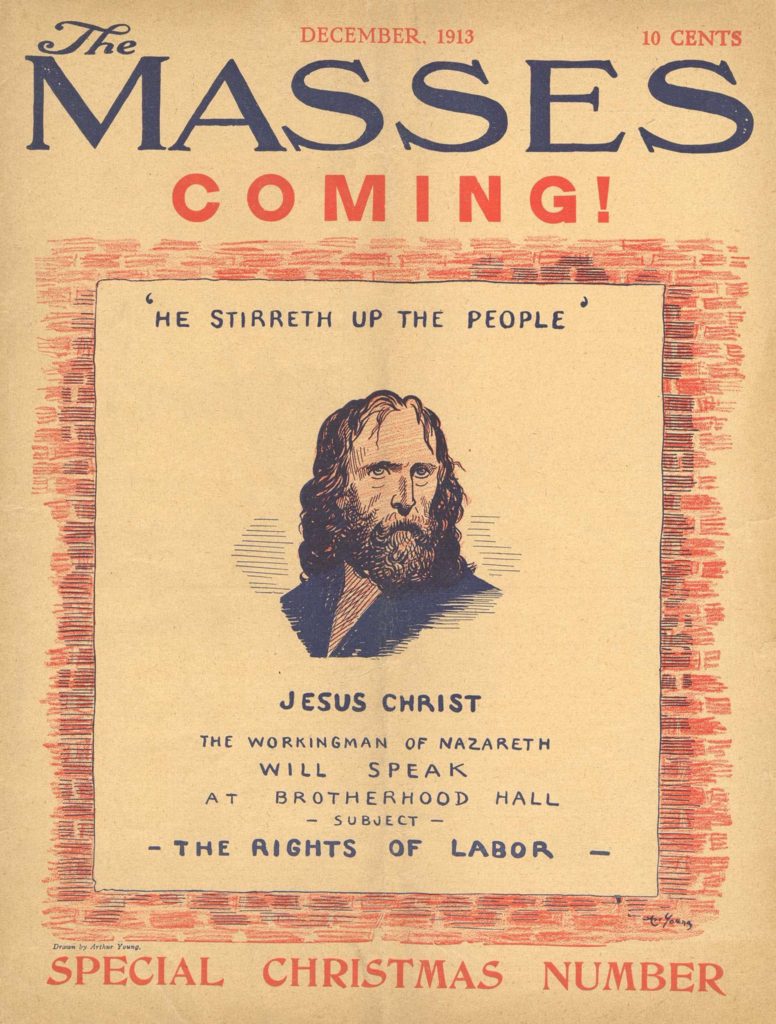

A century and a half ago, Marx closed the Communist Manifesto with what has become one of the most popular slogans in recent political history. He declared that, in order to overthrow the fledgling capitalist system, “workers of the world [must] unite.”1 And yet here we are, in 2020, still stuck in capitalism’s deathly grip and not even close to achieving the unity needed to break free from its grasp.

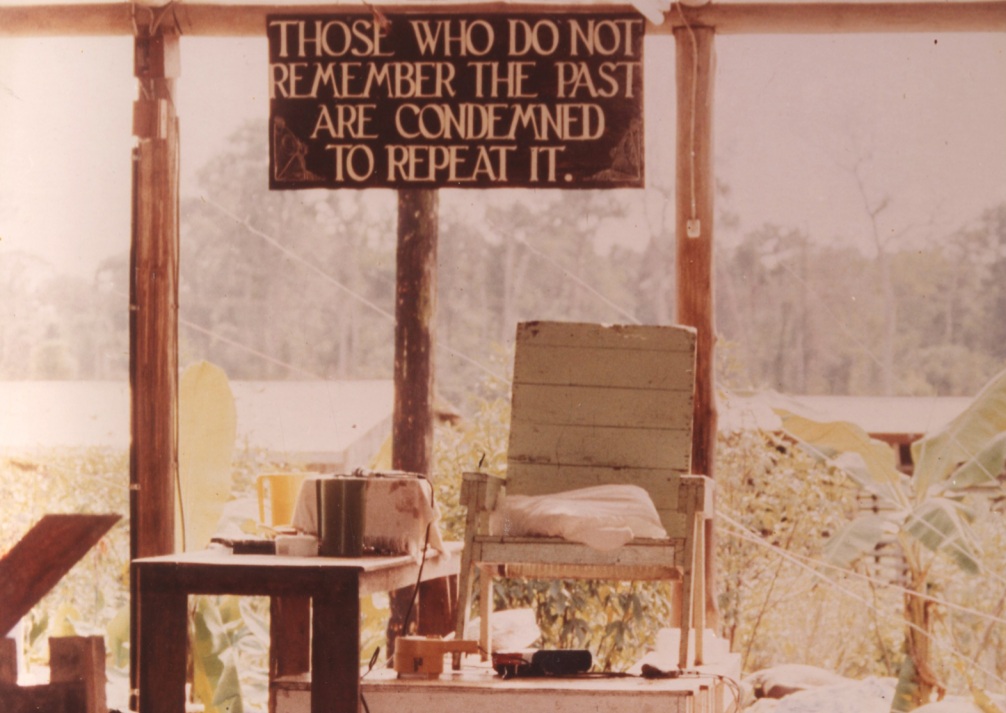

However, this doesn’t mean that no progress has been made. The time between the Manifesto and now has been marked by intense struggles all over the world. We’ve seen the radical experiment of the Paris Commune, the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, the Chinese Revolution, revolutions throughout the Global South, and plenty of revolutionary activity in the imperial core. And yet, none of those revolutions have come even close to shifting their political terrain towards communism, and any of the surviving projects have either drifted towards capitalism or are held hostage by the imperialists. In the US, we now find ourselves in the same position as millions of communists before us. How can we finally overthrow capitalism and move towards the communist terrain? We may answer this question by looking towards the past, but the problem is that history, a site of class struggle itself, hangs over us like a dark cloud. It muddles our perceptions and moves us away from a sober analysis of our concrete situation. With the added influence of the internet, it makes people adopt political positions, accompanied by various signifiers and aesthetics, that have no real concrete bearing on the class struggle.

We are hurtling towards a future marked by intense crises that will expose the deep cracks that exist within the capitalist system. The capitalist system cannot continue without dragging mass death along with it, whether through disease, war, or environmental displacement, and the only solution is revolution.

In Beginnings of Politics, Taylor B argues that the growth of DSA, coupled with the immense uprisings that took place over the summer, are both beginnings of a new form of emancipatory politics.2 Taylor argues that Marxist theory contains a gap, which is the absence of a method for achieving emancipatory politics. While Marxism, “gives us critical tools to understand the capitalist mode of production, the insight that emancipation is immanent to the system through class struggle, and a concept of the transition to communism formulated by Marx as the dictatorship of the proletariat,” it does not tell us the concrete organizational forms needed to achieve these politics. So how do we figure out the kinds of organizational forms we need to achieve our politics? One solution would be to look at prior revolutionary activity, both in the US and abroad, and follow their lead politically. However, and this is at the core of Marxism, the world is always changing. The social formations that comprise the global capitalist system are very different now compared to a century ago. Therefore, the way the class struggle unfolds in our time will necessarily be different from the experiences of our predecessors. In this context, it would be a mistake to dogmatically insist on old forms of organization: forms that were designed as specific interventions within specific struggles. Taylor says, “this is the Marxist problem of politics that must be theorized under the conditions of the current moment, or conjuncture.”

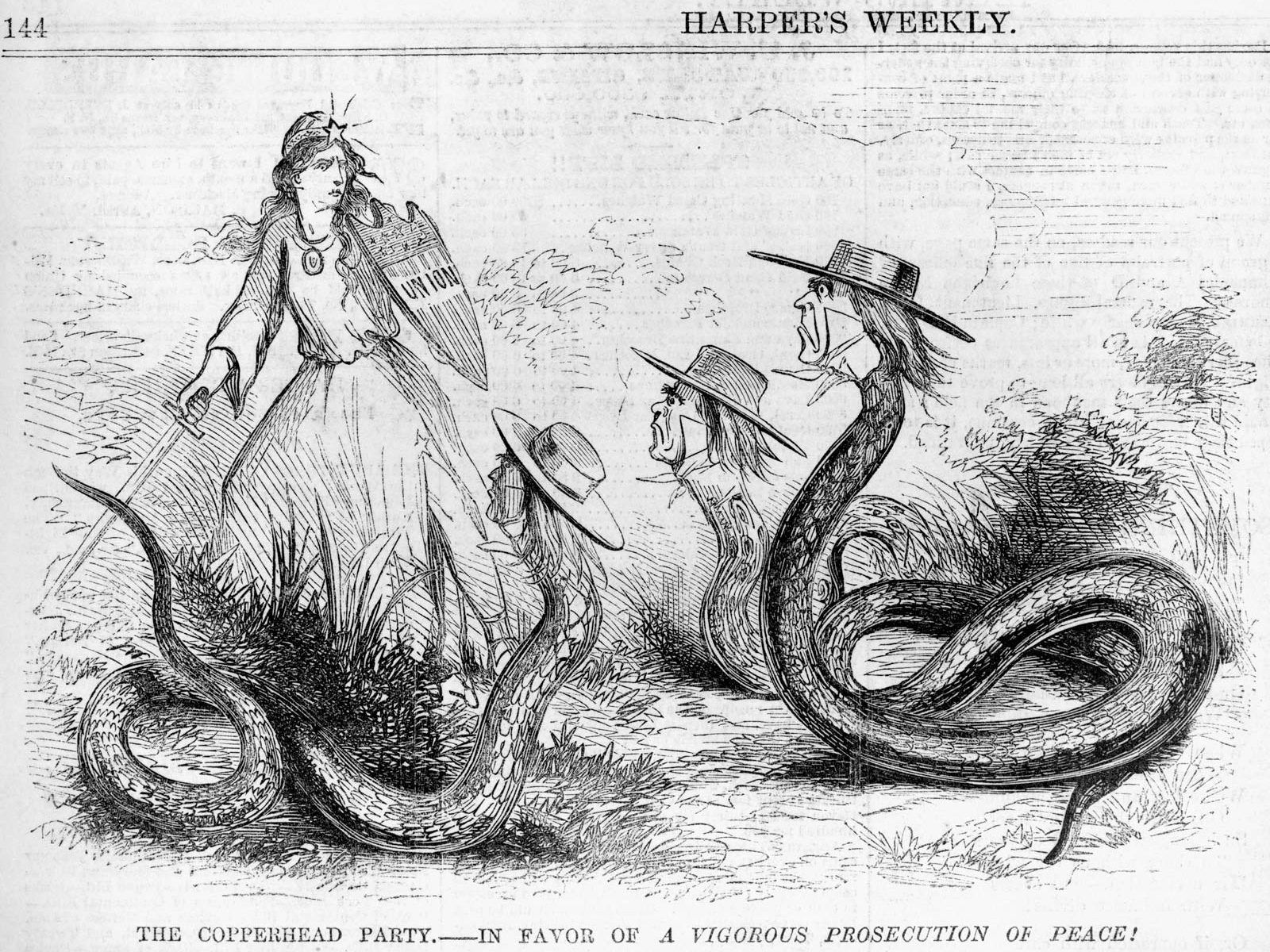

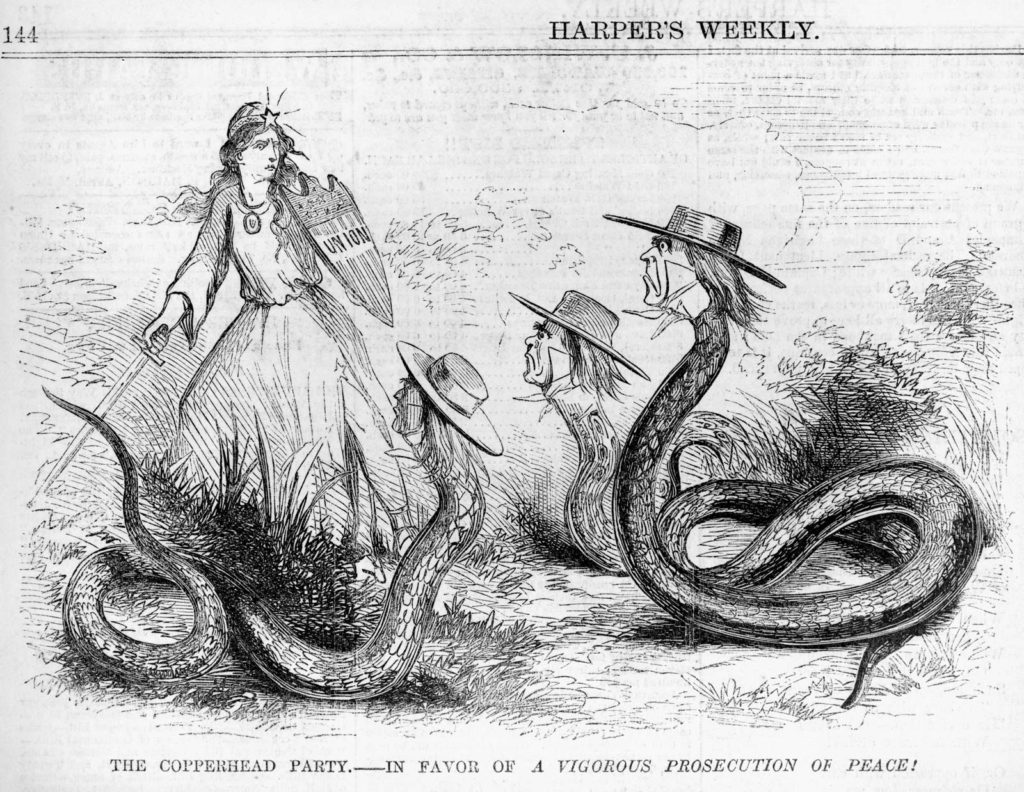

Taylor criticizes the tendency of those on the left to insist on old forms of organization in the current conjuncture. The current conjuncture was born out of the neutralization of emancipatory politics in the 1960s, which is dubbed as the ‘The Black Power Era’. This was the last significant sequence of emancipatory politics in the US. According to Taylor, there were three neutralizing forces of this movement:

-

- The formation of a black middle-class created by an increase in social welfare from the government to appease the Civil Rights movement.

- State repression of radicals, specifically members of the Black Panther Party via COINTELPRO.

- The absorption of the movement by the mainstream, which neutered its radical content.

Taylor’s argument echoes Howard Zinn in A People’s History of the United States, who argues that every revolutionary sequence in the US is neutralized by a combination of purging radicals through incarceration or assassination and buying off the movement via minor reforms.3 Taylor concludes, following Sylvain Lazarus, that the 20th century marked the end of the party form as a legitimate form of emancipatory politics. This is not only because political parties, in this case, the Democrats, Republicans, and even the Black Panthers, played a primary role in neutralizing our last emancipatory sequence, but also because the experiences of socialist construction in other parts of the world demonstrated that the vanguard becomes intertwined with the state, which also neutralized emancipatory politics in those social formations. Instead of falling back on neutralized forms of politics, we must conduct a concrete analysis of our concrete situation, the basis of Marxist analysis I might add, in order to develop novel forms of emancipatory politics.

This new form of emancipatory politics will emerge out of the beginnings provided by the Bernie Sanders movement/growth of DSA and the anti-racist uprisings over the summer. Taylor argues that the rise of DSA and the Bernie Sanders movement demonstrate a common recognition that politics need to go beyond the two-party system. The uprisings, on the other hand, demonstrate a popular anti-racist sentiment throughout the US, which has been directed against the police and the state. While DSA is currently tending towards a couple of different dead-end paths,4 the uprisings represent the potential to resist the neutralization of emancipatory politics. While he does not offer any concrete political form that we ought to build, Taylor concludes that, “we must trust that appropriate emancipatory forms will emerge as we engage in the local, national, and international organizing that this moment makes possible.”

I am sympathetic to Taylor’s general argument that new historical conjunctures necessitate new analyses of the social formation, and, emerging out of this, new modes of politics. This, as I noted earlier, is the immediate task of every Marxist in every social formation. However, Taylor offers us no real solution to the limits of the party-form. He only offers us the vague notion that new forms of political organization will arise out of the current conjuncture through revolutionary practice. In, Without a Party, We Have Nothing, Donald P rightly criticizes him for falling back on a spontaneous conception of revolutionary practice, where it is implied that new emancipatory forms will emerge out of new practices of politics without any planning or strategic outlook developed by revolutionaries beforehand. Following Althusser and Lenin, Donald notes that the absence of an articulated revolutionary theory will be filled by bourgeois ideology, which will itself neutralize these new beginnings.

Donald particularly takes issue with the notion that every major Marxist ruptures from their predecessors. In his piece, Taylor says that, “Marx broke with the utopian socialists. Lenin broke with Marx. The Cultural Revolution can be read as Mao’s break with Marxism-Leninism to free politics from the party-state.” Donald rejects this, arguing that Marx himself had a specific conception of politics, even if it had to be formulated systematically by Engels, Kautsky, and Lenin. Specifically, Lenin’s notion of the party was imported from Kautsky’s merger formula,5 which was developed from the work of Marx and Engels themselves.6 The development of Marxist political practice is defined by continuity, rather than by ruptures, and in the absence of a party, spontaneity will reign.

While I roughly agree with Taylor’s argument on the limits of Marxism-Leninism and the party-form as a neutralization of emancipatory politics, the solution is not to abandon the party entirely. And by party, I mean the revolutionary organization required to harness and lead the revolution.7 For clarification, I am sure that Taylor is operating with a classical understanding of the ‘party’, while I am focusing more on the function of the party as the revolutionary organization which becomes the vanguard of the revolutionary process. Rather, the solution is to transform the nature of the party through the implementation of the mass line. In a word, we can say that while Taylor emphasizes rupture, Donald stresses continuity. But why not both?

The Limits of Marxism-Leninism

Before proceeding into the Maoist terrain on the question of the party, it is first necessary to understand the limits of Marxism-Leninism, and as an extension, the party-form. I believe it is also necessary to define the terms ‘Marxism’ and ‘Marxism-Leninism’, considering the historical baggage and plurality of understandings that each term carries. Following J Moufawad Paul’s (JMP) arguments in Continuity and Rupture, I believe that Marxism is the science of revolution.8 In classical theory, the formula is that Marxism = historical materialism (the science) + dialectical materialism (the philosophy). I believe that this dichotomy misunderstands the specificity of what makes Marxism a science. The crux of scientific practice is experimentation, which means that Marxism must be able to test its theories. The only way that Marxism can test its theories, which are produced by historical or dialectical materialist analyses of a social formation, is through political practice.9 So while they are not what makes Marxism scientific per se, historical and dialectical materialism are the scientific methods that make Marxist political practice possible. While I don’t have space here to articulate the specificity of the characteristics of science and Marxism’s claim to it, JMP makes two important claims on the subject.

The first claim is that a science can never be closed off to the future. If it is, it will no longer be capable of producing any knowledge, rendering it obsolete. A science must always be open to further theorization and development in order to be useful. This is compatible with dialectical materialism, which asserts that the world is always changing. In this view, science is a truth process, and not the content which is the end-result of that truth process. Or in other words, science is defined by its practice and not by its results. For Marxism, this means that its claim to science is determined by the practice of creating communism, and not by the particular lessons we learn during this process.10

The second claim is that every science is defined by the dialectic of continuity and rupture. Continuity because every science builds on the insights of its predecessors, and rupture because every science eventually encounters its own internal limits, which necessitates a rupture in the paradigm to overcome said limits. The unity of a revolutionary tradition comes from shared insights, premises, and methodologies. Every stage accepts the universal lessons produced by the previous stage. To summarize, JMP says,

In the unfolding narrative of any living science (what Simone De Beauvoir categorized as ambiguity or what Alain Badiou called a truth procedure) moments of rupture are simultaneously moments of continuity. The rupture preserves the continuity; simultaneously, the continuity informs the rupture. Sometimes, in order to declare fidelity to the core principles of a science, a rupture is required: on one level theory is rearticulated and revised, and all dogmatisms abandoned, in order to prevent the deeper revision (that is the abandonment) of the basis upon which this science is possible. If a set of problems within a given science cannot be solved then there are two options: an abandonment of this science’s trajectory and a rejection of its core premises (i.e. abandon physics for spiritualism in order to seek a solution in superstition), or an abandonment of a specific scientific paradigm in order to reboot the core premises within a new theoretical region.11

In the case of Marxism, ruptures in science occur through the experiences of world revolutions. The three world-historical revolutions to have happened so far are the Paris Commune, The Russian Revolution, and the Chinese Revolution.12 We must also note, like Lazarus, that every revolutionary sequence eventually fails. However, Moufawad-Paul argues that not all failures are the same, and he distinguishes between four types of revolutionary failure. There are:

a) those possible failures that are encountered because they result from new questions the previous revolutions did not encounter; b) those possible failures that the most recent world-historical revolution encountered but did not solve. c) those possible failures that the most recent world-historical revolution encountered and did solve. d) those failures that were solved prior to the most recent world-historical revolution, by earlier revolutions in the sequence.13

The first two deal with failures that lurk beyond or at the horizon of revolutionary history, which makes them live failures. The last two deal with failures that are contained within or before revolutionary history, which makes them dead failures. Any dead failure of a revolution did not learn from the history preceding it.

To summarize so far, Marxism is the science of creating revolution, which depends on the methodology of historical and dialectical materialism, and it moves into new stages via the experience of world-historical revolutions. As Moufawad-Paul notes, the first world-historical revolution in the Marxist paradigm is the Paris Commune, where the workers of Paris controlled the city for two months before eventually being neutralized by imperialist forces. The Paris Commune failed because it was not able to defend itself from the French army, which massacred thousands of Communards in the streets of Paris. As Lenin argues in State and Revolution, it was Marx and Engels experience of the Paris Commune which led them to the conclusion that, “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.”14 Lenin clarifies, “Marx’s idea is that the working class must break up, smash the “’ready-made state machinery’, and not confine itself merely to laying hold of it.”15 The experience of the Paris Commune demonstrated that it was not enough to merely seize state power, and that the immediate goal of the revolution is to defend its own existence by repressing the bourgeoisie.

Marxism, in its form at the time, encountered significant problems in the experience of the Paris Commune. On the one hand, Marx argued that the conditions of capitalist production will create an organized working class that will overthrow the bourgeoisie. On the other hand, Marx’s political activity demonstrates that it is necessary for communists to intervene in the process of political organization. Since Marx argues that revolutions in a mode of production are the result of its own contradictions, interpreters imply that this process will be spontaneous. We can draw an analogy here with the problem of free will. If everything that happens in an individual’s life is determined by forces outside of their control, does this imply that the individual ought to do nothing? This problem, between a bird’s eye view of history where events ‘seem’ inevitable and the concrete question of how these events are produced by individuals, can be resolved if we make a distinction between different domains of knowledge.

Marx’s ‘prediction’ of global communist revolution was a product of his analysis of history and the capitalist system during his own lifetime. Or in other words, Marx was making a historical claim that every mode of society, no matter how strong it seems at the time, will be overthrown because of contradictions that exist within it. Marx did not argue that this process will occur spontaneously, rather, it is the duty of communists to impart to the working masses with the theory needed to consciously create a revolution. Returning to the point, the Paris Commune significantly challenged Marx and Engels’ own beliefs about the durability of the capitalist system,16 their sense of historical time,17 and the level of organization needed to overcome it. As Taylor argued, Marx, who was necessarily limited by his place in history, could not fully theorize the political forms needed to overthrow capitalism. It wasn’t until Lenin and the Bolsheviks that the problem of the revolutionary political form was coherently theorized.

If the Paris Commune failed primarily because it was not able to defend itself, then the immediate task of every revolutionary movement is to develop the means to defend itself immediately after the seizure of state power. Lenin’s insights tell us that, “it is only possible to establish socialism through a revolutionary party, [and] that a state commanded by the proletariat must be instituted to suppress the bourgeoisie so as to possibly establish communism (i.e. the dictatorship of the proletariat).”18 While Marx had already argued that the dictatorship of the proletariat would immediately follow the revolution, Lenin took this a step further and argued that the DOtP will need to be realized by a vanguard party that actively leads the revolution. Or in other words, Marx believed that a communist revolution would be won by an organized group of workers created by the conditions of capitalism, but he did not know how this would unfold concretely. Lenin argued that the workers alone would not be able to successfully lead a revolution if they did not possess revolutionary theory. Therefore, it is the Communist Party’s duty to develop revolutionary theory and spread it to the workers. The Communist Party becomes the vanguard by harnessing and directing the revolutionary energy of the masses.

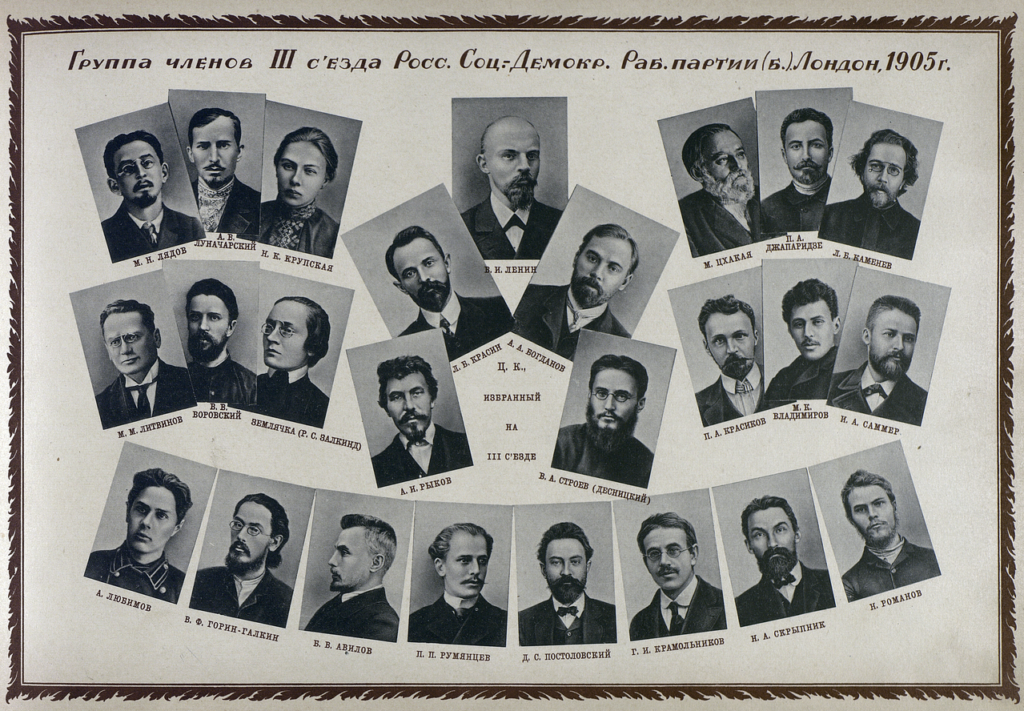

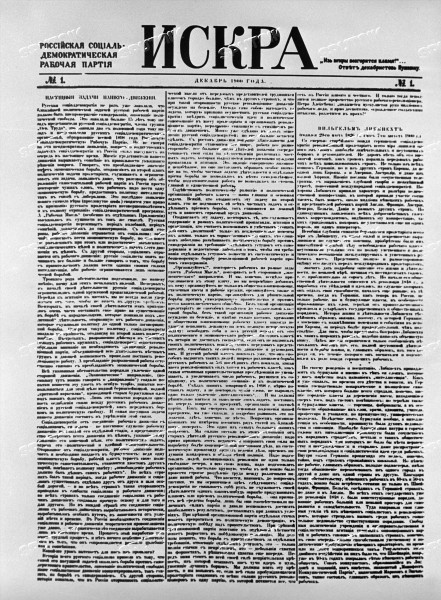

And Lenin was right: his concept of the DOtP and the vanguard party worked. The Bolsheviks not only seized state power in Russia with the broad support of the masses,19 but they were also able to hold on to it too despite a full-fledged imperialist onslaught. It was the success of the Bolshevik Revolution that opened up a new paradigm within the science of Marxism, which became codified as Marxism-Leninism. Of course, we must note that Leninism is a placeholder for the rupture provided by the Soviet experience, and wasn’t actually codified systematically until Stalin’s Foundations of Leninism, where the specificity of Leninism was articulated for the first time. Likewise, JMP argues that Maoism itself didn’t become an actual concept until it was systematized by the Communist Party of Peru in the late ’80s.20 Lenin was a Marxist, but it was his application of the methodology to the Russian conditions, and the success of the revolution, that transformed the paradigm and taught us new universal lessons in the process.21

However, we all know that the Sovet Union failed. The Communist Party, which became intertwined with the state, became more and more alienated from the masses. The weakening of the Soviets, which Lenin envisaged as the ideal form of proletarian democracy, coupled with the absence of mass organizations to hold the Communist Party accountable, played a major role in this breakdown. While the Soviet Union was a failure, it was a live failure because it encountered limits unknown to any previous socialist project. The USSR not only rocked the capitalist nations to their core (the Red Scare), but it also showed us that it is possible to build a world beyond the capitalist system. And even though the USSR did a lot of bad things, like the purges, the invasions, and unnecessary repression, it was a significantly better society than the liberal democracies. We don’t need to accept bourgeois historiography and bash the Soviet Union for not actually being communist. Rather, we need to learn why they failed, and find solutions to their failures.

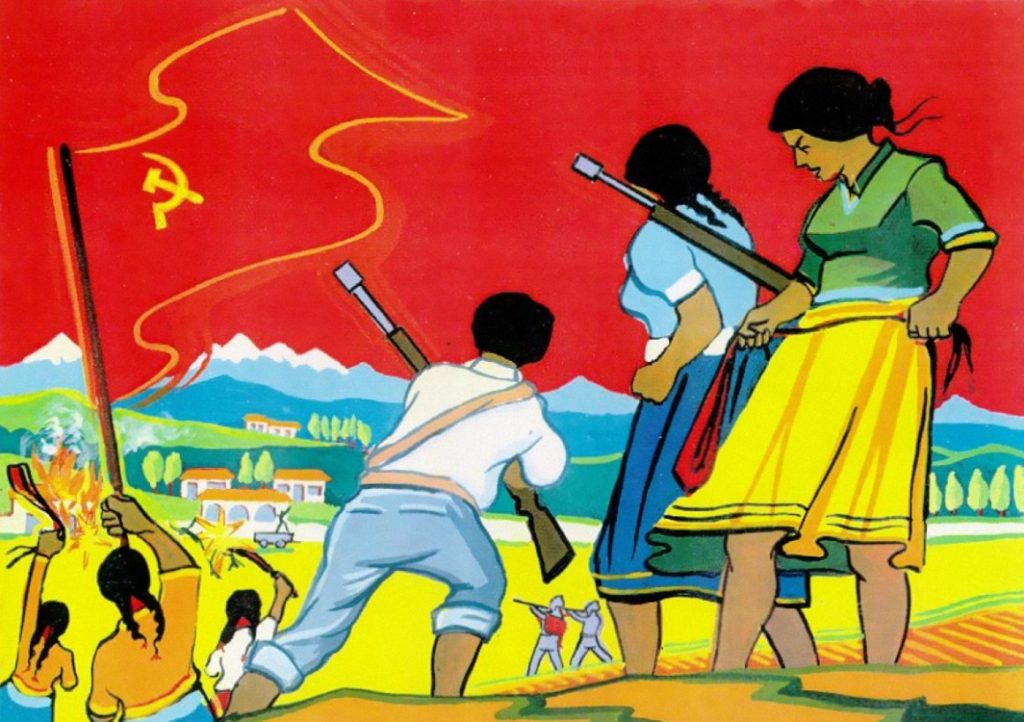

The Maoist Rupture

One explanation for the failure of the USSR, and therefore of Marxism-Leninism, is argued In The State and Counter-Revolution. The author, Tom Clarke, argues that Marxism-Leninism is necessarily defined by the following contradiction:

On the one hand it is impossible for the proletariat to spontaneously develop a revolutionary party with a revolutionary ideology; on the other hand, it is impossible for a party that the workers cannot possibly develop, and thus is developed instead by the petty bourgeoisie, to carry a revolution to its completion. In essence: Marxism-Leninism is correct while, at the same time, Marxism-Leninism is incorrect.22

Clark’s argument entails the view that the intellectuals who import revolutionary theory to the proletariat, i.e. the merger theory, are of petty-bourgeois origin. Clarke views this contradiction of Marxism-Leninism in the positivist sense, in which contradictions are irrational and undermine a theory. Moufawad-Paul disagrees and views this as a contradiction in the Marxist sense, i.e. as a problem that needs/must be overcome. We cannot simply dismiss this contradiction as non-existent, or even try to pick one side of the contradiction, where we would either declare that only the workers or the intelligentsia can lead us to revolution. One example of the former comes through Hal Draper, who tried to solve this problem with a theory of “socialism from below” where the working class spontaneously builds their own party. Moufawad-Paul argues that Clarke’s inability to solve the contradiction was because of his misunderstanding of Maoism as Mao Zedong-thought. Furthermore, the Cultural Revolution provides the seeds of the solution to the impasse of Marxism-Leninism (a struggle against petty-bourgeois ideology).

Before proceeding into the Cultural Revolution, it is necessary to provide a schematic overview of the relationship between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). If the Bolshevik Revolution built on the failures of the Paris Commune, then the Chinese Revolution built on the failures of the Bolsheviks. Although, we must add that the Chinese Revolution unfolded during a similar time period to the Soviet Union’s socialist construction, which meant that there wasn’t enough time in between for them to fully comprehend the USSR’s failures.23

Mao and the Chinese Communists had seen the process of alienation between the party and the masses in the USSR. A major component of this process was the development of revisionism within the CPSU. Midway through the 1930s, the CPSU was already declaring that socialist construction was complete within the USSR. Walter Rodney says, “we ought to be skeptical of the Soviet claims of having fully achieved Socialism in 1937–8 and that they are now building Communism. That they can pin down a precise date is immediately suspicious.”24 It is clear that at this point, even before Kruschev, the USSR was already drifting towards revisionism. While improving material conditions and developing a previously underdeveloped country is a good thing, this is not socialism. Mao was understandably worried that China could also slide down the revisionist road. Therefore in China, party officials didn’t attain the same privileges as Soviet officials. They only consumed what they needed, rode bicycles or took buses for transportation, and ate meals in workers’ canteens.25

The Chinese Communists developed the mass line to counter the development of revisionism within the party and to ensure that the party always remained accountable to the people. So what is the mass line? JMP says,

The participants in a revolutionary movement begin with a revolutionary theory, taken from the history of Marxism, that they plan to take to the masses. If they succeed in taking this theory to the masses, then they emerge from these masses transformed, pulling in their wake new cadre that will teach both them and their movement something more about revolution, and demonstrating that the moment of from is far more significant than the moment of to because it is the mechanism that permits the recognition of a revolutionary politics.26

The mass line ensures that the party is always held accountable by the people. If the masses reject a theory, then the party must too. One may object that this converts the masses into the sole arbiters of truth, which can be potentially problematic. If the masses are the sole arbiters of truth, then why does the party exist in the first place? However, this is not what the mass line implies. Rather, “if [a theory] is rejected by the most radical factions of this class then it should be rethought; if it pulls in new recruits, who will also transform the movement that brings this theory, then it is not some alien affectation imposed on the working classes.”27 No class or organization is the sole arbiter of truth, and the only way to determine the truth is through testing theories. Knowledge is the result of experimentation and ideological struggles, not something that is revealed (empiricism) or discovered through thought alone (rationalism).

Unfortunately, the Maoists were too late to realize the development of revisionism within the party, which was manifesting in the alienation of the people from the party. By 1951, the party created a salary system for party officials, some received better pay and benefits, and it even opened schools specifically for party members’ children, despite Mao’s opposition. After the failure of the Great Leap Forward, Mao was ousted from power within the party. However, he wasn’t willing to give up just yet, which takes us back into the Cultural Revolution, which, Alain Badiou notes, “was the sole example of a revolution under the conditions of state socialism.”28

While this isn’t a space to analyze the immense complexity of the GPCR, which others are already doing, I can, again, provide a schematic overview. The Cultural Revolution was a revolution led primarily by young Maoists, who were emboldened by the support of Mao, against bourgeois elements in China and particularly against Party officials. The Revolution took the form of the Red Guards storming cities with military equipment and conducting public struggle sessions, power seizures by the Red Guards in cities like Shanghai where anti-Maoist public officials were purged and even publically humiliated, and the construction of various mass organizations that were external to the party. Another significant event to happen in the Cultural Revolution was that students were sent to the countryside to learn manual labor, and workers began to occupy the universities. In one particular incident, students responded to the occupation by shooting at and killing workers, which required an intervention from Mao himself to de-escalate the situation. The Cultural Revolution was one of the most significant, dramatic, and violent episodes of the 20th century, and I cannot even come close to giving it the justice it deserves here.

What matters here is not necessarily what happened in the Cultural Revolution, but why it happened in the first place. The 16 Points document, produced by the Maoists, provides the general motivation for the Revolution:

Although the bourgeoisie has been overthrown, it is still trying to use the old ideas, culture, customs and habits of the exploiting classes to corrupt the masses, capture their minds and endeavour to stage a comeback. The proletariat must do the exact opposite: it must meet head-on every challenge of the bourgeoisie in the ideological field and use the new ideas, culture, customs and habits of the proletariat to change the mental outlook of the whole of society. At present, our objective is to struggle against and overthrow those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic “authorities” and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art and all other parts of the superstructure not in correspondence with the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.29

The Cultural Revolution can be understood as a revolution in the superstructure of the socialist social formation. While the initial Chinese Revolution seized state power, another revolution was necessary to defeat the persistence of bourgeois ideology, customs, and traditions. Furthermore, this revolution would have to remove power from revisionists within the party. This brings us to a key insight of Maoism, which is that after a revolution, the bourgeoisie re-constitutes within the party.

We must note that all developments in Marxist theory can be considered, on some level, to be ‘revisions’ of Marx. But to add on to, or to criticize Marx, does not make on a revisionist per se. Rather, revisionism occurs when one rejects the core premises of Marxism. The core premise of Marxism is the law of class struggle which leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet Union became revisionist when they sought collaboration with the United States. If the Soviet Union represented the global communist movement, and if the US represents the global capitalist system as its strongest link, then pursuing peace for peace’s sake is a negation of the core of Marxism.

In The Cultural Revolution, Jean Daubier attempts to explain why revisionism necessarily develops within the party post-revolution. To start with, he notes that every revolution inherits contradictions from the social formation preceding it. In every society on Earth, since there are no communist societies, there is a division of labor between manual and intellectual labor. In capitalist societies, we treasure intellectual labor and treat manual labor with contempt. All of our lives, we’ve been told to look down upon menial labor, such as being a factory worker, working at McDonald’s, being a mailman, etc. The jobs that children aspire to are usually doctors, lawyers, teachers, etc.30 In other words, jobs that mainly consist of intellectual labor and are occupied by trained intellectuals. Daubier argues that this division of labor, and further, the perceptions associated with each form of labor, necessarily carry into a socialist society. He argues the university is a prime site of the division of labor. Of course, a socialist society still needs universities to train people in the sciences, technology, etc., but unless they’re dramatically overhauled they’ll reproduce the capitalist division of labor. This is the, “opposition between the bearers of knowledge on the one hand and the mass of workers, deprived of science, on the other.”31 Thus, even though capitalism has been abolished, some of the contradictions inherent in it will remain under socialism.

Furthermore, Daubier argues that, by force of habit, it is more likely than not that the lionization of intellectual labor will remain in a socialist social formation, and a division between an elite class of scientists, technicians, and administrators will form at one pole while the workers will remain at the other. The state, which always maintains and reconciles class antagonisms, even after the revolution, still exists under socialism and can perpetuate inequality between party officials and the masses. Those in power have the opportunity to attain certain privileges for themselves, and Daubier argues that this happened in the Chinese CCP. The struggle against individualism and egoism in the party can turn into a major struggle on its own. This is the context of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, which seems like a perfectly “logical Marxist endeavor.”32 Daubier concludes, “at the heart of the Cultural Revolution was the relationship between those in power and the people.”33

So what lessons can we draw from the Cultural Revolution? Let’s return to Badiou’s analysis in The Communist Hypothesis, where he argues that the Cultural Revolution:

bears witness to the impossibility truly and globally to free politics from the framework of the party-state that imprisons it. It marks an irreplaceable experience of saturation, because a violent will to find a new political path, to relaunch the revolution, and to find new forms of the workers’ struggle under the formal conditions of socialism ended up in failure when confronted with the necessary maintenance, for reasons of public order and the refusal of civil war, of the general frame of the party-state.34

Returning back to Taylor’s piece, his debt to Badiou becomes clear. While Badiou praises the project of the GPCR for being the first proletarian revolution within a socialist society, he makes the wrong conclusion. Badiou understands the limits of Marxism-Leninism and the party-form, which becomes divorced from the people and facilitates the development of revisionism and capitalist restoration, but does not believe these limits can be overcome, at least within the framework of the communist party. The only problem was that the necessity of the Cultural Revolution was realized too late, which meant it couldn’t override the drift towards the capitalist road. Moufawad-Paul argues that Badiou draws these hasty conclusions because not enough time had passed for him to realize that the Cultural Revolution spawned the development of new revolutionary movements in Peru, Nepal, Afghanistan, etc, where Maoism was formulated coherently for the first time.35

This brings us back to Tom Clarke and his critique of Marxism-Leninism. Clarke seems to argue that revisionism is inevitable due to the petty-bourgeois essence of Marxism-Leninism. However, according to JMP, “Clark ignores that one moment in history [The GPCR] where the petty bourgeoisie was ‘sent down to the countryside’ in droves, where once-privileged Marxist intellectuals were placed under the authority of the masses, and where the authority of the party itself was briefly called into question.”36 The Chinese Revolution encountered Clarke’s contradiction where the petty-bourgeois re-formulates into the party because after a revolution, petty-bourgeois ideology still permeates society. However, the Cultural Revolution proposed a way to transgress this limit of Marxism-Leninism.

To clarify, both the Soviet Union and China demonstrate the limits of Marxism-Leninism. Revolutionary China was a Marxist-Leninist project and came up against the same limits as the USSR. The difference was that China offered solutions to overcome these limits, even if they failed (in the live sense), which opened a new paradigm in the science of Marxism: Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. The Mass Line offers a mechanism to transform the nature of the party into a revolutionary mass organization which can resist the neutralizing force of the party-form.

Maoism in the Current Conjuncture

Returning back to where we started, how can we apply the insights of Maoism to the current conjuncture? To start with, we need to apply the mass line, criticism and self-criticism within our organizations and begin the process of cultural revolution. JMP believes that any revolutionary organization should be posing these questions:

Is an organization building itself according to the will of the revolutionary masses while, at the same time, organizing this will and providing theoretical guidance; is this organization critical of itself and willing to accept that it is wrong; are the movement’s cadre serving the people and capable of self-criticism in a way that parallels the “checking of privilege” common in identity politics circles but, unlike these circles, tied to a coherent political line; does this movement see itself as capable of transcending the ruling ideas of the ruling class, grasping how certain ideological moments distort and over/under-determine the economic base (as Mao pointed out in On Contradiction), and constantly reforming itself through the long march of cultural revolution? Failure to answer these questions might in fact be a failure to concretely apply those theoretical insights that are supposed to make the name of Maoism into a concept.37

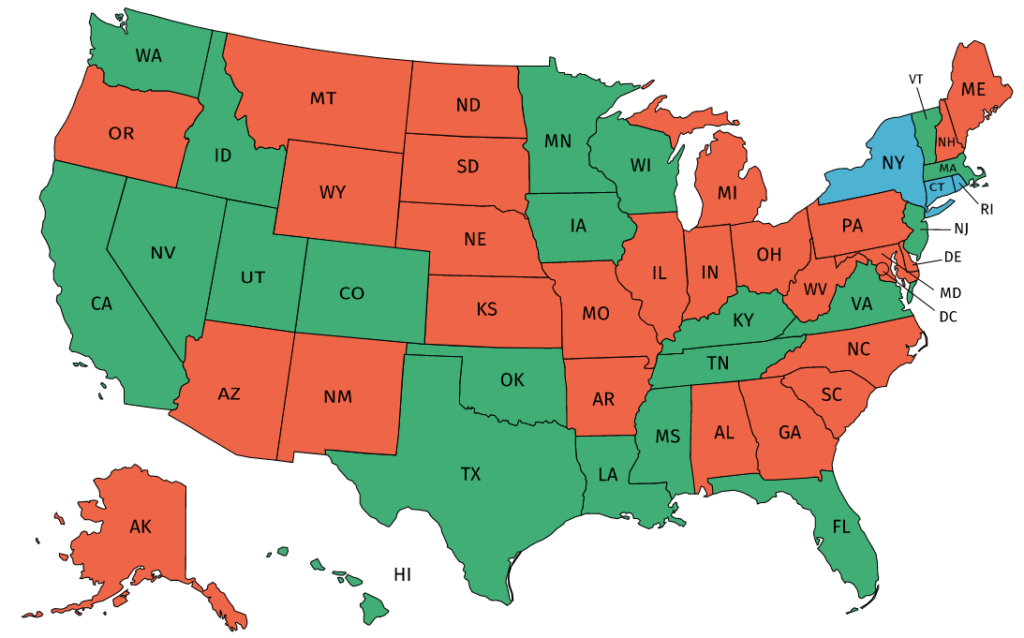

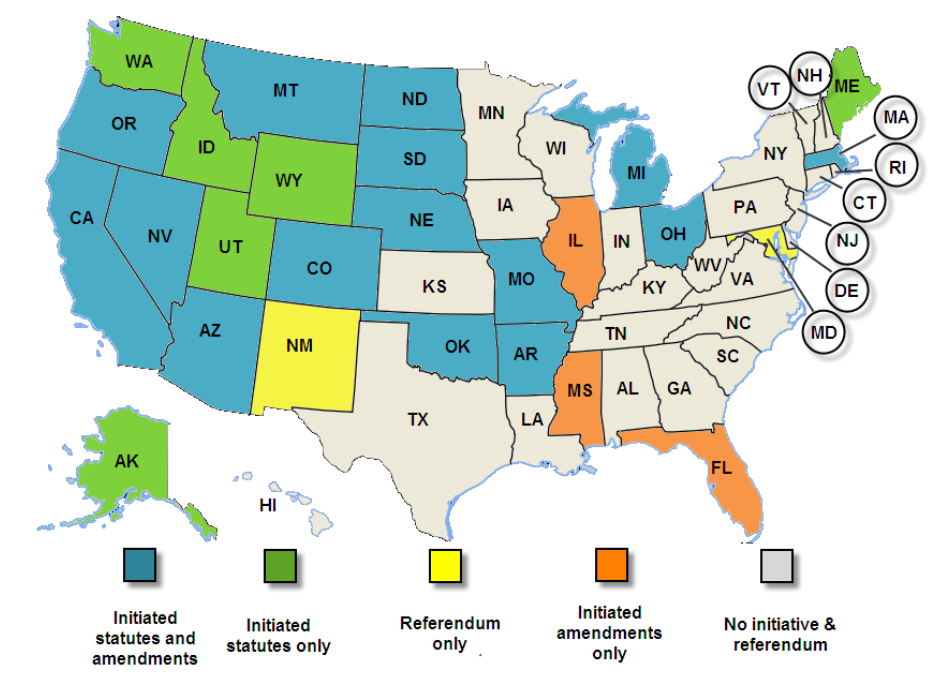

I also believe it is important to determine, right now, which organizations have the capacity to be revolutionary. The biggest socialist organization in the US right now, as we are constantly reminded of, is DSA. Is DSA capable of becoming a revolutionary organization that implements the mass line?

This question can be answered with a firm no, as DSA is a dead end. One reason is that sexual harassment and assault run rampant within the organization and are even covered up by leadership on occasions.38 Although as we have seen recently with PSL, this is not unique to DSA alone. We cannot build a truly revolutionary organization without taking instances of harm seriously. Nevermind the personal trauma that sexual harassment and assault inflict, but if communist organizations demonstrate that they are incapable of standing alongside survivors this will create intense disillusionment and distrust within the communist movement. I have plenty of comrades that have become disillusioned with revolutionary politics because of their experiences within DSA.

DSA is also a dead-end for political reasons because their success is built on a bourgeois understanding of socialism. I have met so many individuals, both in DSA and in YDSA, that believe socialism revolves around the struggle for social welfare like universal healthcare and education. This is not a problem per se, considering the core of any communist movement’s activity will revolve around political education and inheriting individuals with petty-bourgeois beliefs. But the problem is that DSA actively facilitates the recruitment of these individuals through their political practice, which revolves around electing ‘socialist’ politicians into the repressive state apparatus, or fighting for legislation. DSA actively vulgarizes the common perception of socialism, and embodies opportunism. I would be more sympathetic to the argument that revolutionaries ought to stay in DSA if the organization did not actively harm the communist movement by vulgarizing socialism and inflicting harm on individuals.

This piece doesn’t have the scope to present a full argument for what kinds of organizations we ought to be building or participating in right now, but I can say that communists should be building explicitly revolutionary organizations and following the mass line in their practice. It doesn’t matter if these organizations are already existing, like the Maoist Communist Party chapters that have been forming recently, or if they are being constructed now on a smaller scale. As Lenin says,

It is not so much a question of the size of an organisation, as of the real, objective significance of its policy: does its policy represent the masses, does it serve them, i.e., does it aim at their liberation from capitalism, or does it represent the interests of the minority, the minority’s reconciliation with capitalism? And it is therefore our duty, if we wish to remain socialists, to go down lower and deeper, to the real masses; this is the whole meaning and the whole purport of the struggle against opportunism.

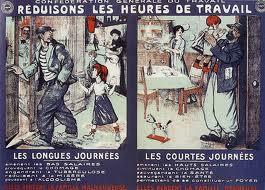

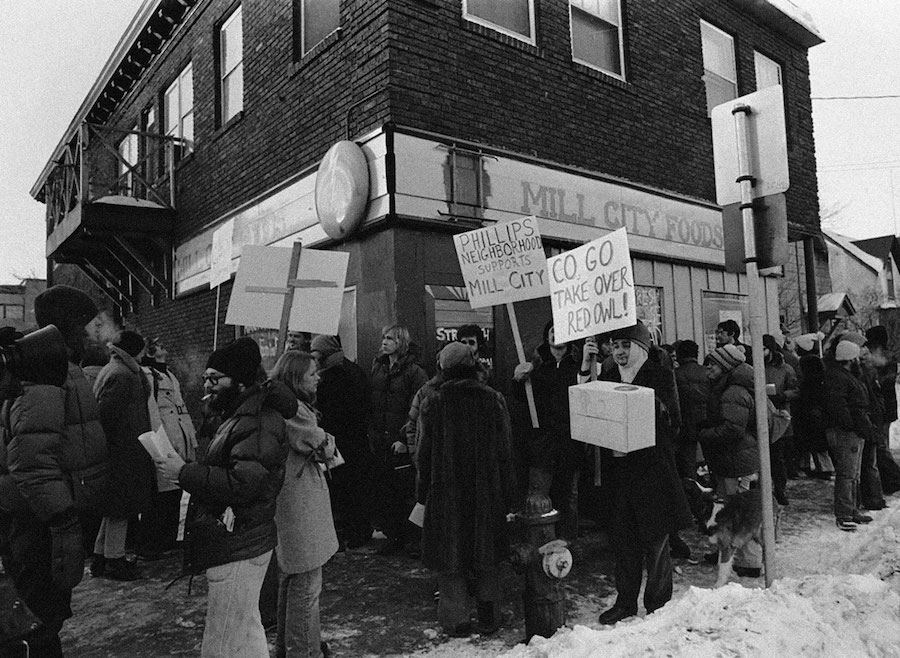

This idea, of serving and interacting with the masses, is at the basis of the mass line. Only by actually building relationships with the people most intensely exploited and oppressed by the capitalist system, the primary revolutionary agents, can we begin to form a revolutionary politics. The uprisings present a clear opening for the implementation of the mass line. It is clear that the masses are being unjustly imprisoned and killed by the bourgeois state. It is clear that the masses are being left like sheep to the wolves in this pandemic, where working class people are being ravaged by Covid without any help from the state. It is clear that the masses are still being forced to work despite a deadly pandemic. If we want to build a revolutionary movement, we need to start by supporting the masses where they are right now, figure out their needs, and demonstrate our solidarity.

This process cannot stop and end at service.39 Rather, this is the beginning of the process of building a revolutionary communist organization, guided by the mass line, which can overcome the neutralizing forces of the bourgeois state and their lackeys.