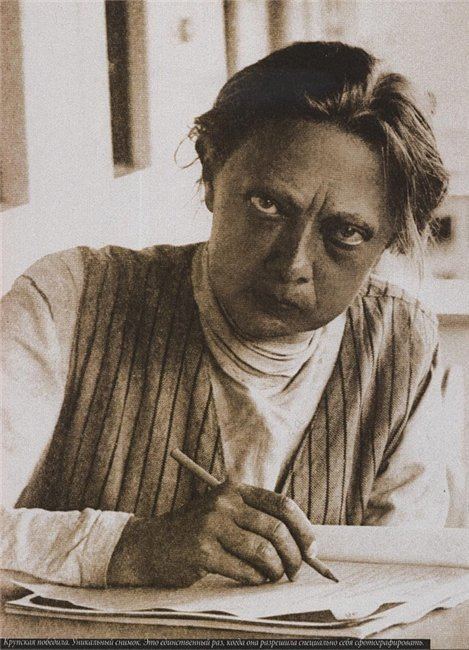

Translations by Mark Alexandrovich, introduction by Mark Alexandrovich and Renato Flores.

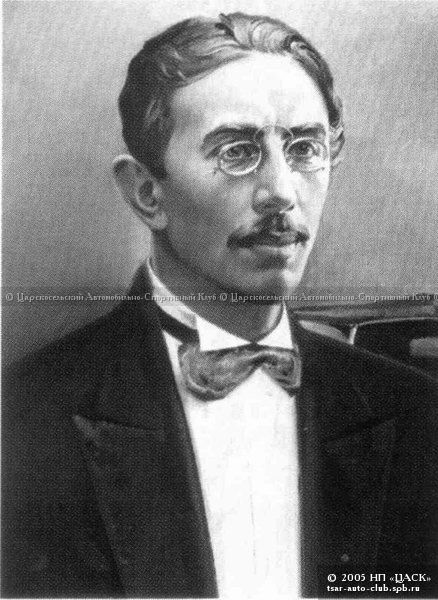

Osinsky is the pseudonym of old Bolshevik Valerian Valerianovich Obolensky. Born in 1887, Osinsky is an often forgotten but very influential Bolshevik and theoretician. He started off on the left-wing of the Bolsheviks, being active around the journal Kommunist. After the revolution, he became chairperson of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy but lost that position due to his opposition to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. He was elected in 1919 as a delegate to the founding congress of the Communist International, and in this same year became part of the oppositional tendency, or unofficial faction of the Democratic Centralists, alongside other figures such as Sapronov and Smirnov.

The Democratic Centralists, or Deceists, were a tendency within the Bolshevik party who came together on the basis of attempting to reform the organizational structures of the nascent Soviet state. In particular, they questioned the existing relationship between the party and the state, which they saw as inefficient and undemocratic. They were concerned with the proliferation of unresponsive bureaucracy due to either excessive centralization, duplication, or triplication of roles that were supposed to deal with the same competencies. They also heavily opposed the encroaching militarism of the government which was caused by the civil war. They realized that this was demobilizing the workers and disenchanting them from the idea that the Soviet government was their own. During the brief time during which they were active, they pushed for more debate, and more collegiality at all levels, proposing new ways of running the government. They became moribund after the 10th Communist Party Congress, which alongside approving most of their demands, also approved the temporal ban on factions.

Below, we present two texts from Osinsky which have never been available in English: an article from Pravda in January 1919, and a speech from the 8th Communist Party Congress. The former text’s original scan is unreadable in places in the digital scans, so if anyone has or knows of a complete copy we invite them to make it available to us. This text is meant for a more popular audience, even if some sentences are long and convoluted. If some passages are confusing in English, they are like that in the original Russian, too. The translator tried to make it clearer where possible. Osinsky’s language is also old fashioned, even for 1919. This could either have been the way he wrote or purposeful use of old fashioned, peasant language for his audience. The second text’s source was much clearer as the proceedings from the 8th Communist Party Congress are fully available in digital format. This text also does not have the old-fashioned language and is overall an easier read.

Osinsky was one of the most prominent members of the Demcents. These texts we present are an important exhibit of the type of diagnosis and reforms proposed by the Deceists in order to improve Soviet democracy and make it a true government of the people. Like many of their contemporaries (such as Krupskaya), the critiques from the Deceists were constructive and presented as resolutions with actionable points in the congresses of the Communist Party. We present this text with two intentions. First, to show the vibrancy and depth of Bolshevik debates in general; unfortunately, in modern-day “common-sense” historiography the struggle is too often reduced to the two poles of Stalin and Trotsky, forgetting everyone and everything else constituting Soviet life and government. This text from 1920 is prior to Trotsky’s critiques of bureaucratization in 1923, and in many ways opposes Trotsky’s politics at the time of the text regarding the militarization of the state. Second, this text clearly shows that the Bolsheviks realized quite early that forming a workers state was not going to be as easy as expected, and that the tasks of government and the articulation between Party and State, and between centralization and decentralization, were extremely complex. In this context, the diagnostics and resolutions of Osinsky, although opposed by Lenin and heavily voted down in the 8th Congress, are crucial for understanding the development of the Soviet government.

Osinsky, alongside many Deceists, would later sign the Declaration of 46 in 1923, a communique to the Central Committee which asked for urgent reforms to solve the increasingly aggravated problems of government malfunction. The Deceists would end up fracturing, with many (including Osinsky) joining the Left Opposition. Some Deceists like Sapronov and Smirnov would end up expelled from the party, going as far as characterizing the USSR as state capitalist and unworthy of defense. Osinsky would end up aligned with Bukharin’s views on the peasantry, and served as Professor of the Agricultural Academy of Moscow. With the downfall of Bukharin, his protection disappeared. Like many Old Bolsheviks, Osinsky would be executed during the Purges, on the first of September 1938. However, the issues and problems that Osinsky raises here are still as relevant today as ever as other problems of socialist transition.

Further readings:

Lara Douds, “Inside Lenin’s Government: Power, Ideology and Practice in the Early Soviet State”, Bloomsbury Academic, 2008

David Priestland, “Bolshevik ideology and the debate over party‐state relations, 1918–21”, Revolutionary Russia Volume 10, 1997 – Issue 2

Going Back or Moving Forward

Pravda, 15 January 1919

“Ah, yes, you preach no more no less a return to ‘democracy’, your reasoning smells a lot of liberalism”, we have already heard the objection from some comrades. Such comrades have not learned at all of our attitude to democracy, to populism. By renouncing the so-called “democratic republic”, we gave up bourgeois parliamentary democracy. We gave up its foundation, the capitalist mode of production, which provides in such a republic a financial dictatorship. We have renounced all the formal features of a “democratic republic” that, in words, give rights to the people and, in fact, ensure the domination of the bourgeoisie: universal (rather than class) suffrage; essentially irreplaceable elected bodies detached from the masses; separation of powers, transforming parliaments into legislative institutions: independence and irreplaceability of officials; universal and formal civil “freedoms”.

But we gave up all this only in order to secure the dictatorship of the widest masses of the working people and to create a true people’s rule of law, a worker-peasant democracy. The Soviet republic is the only form of real democracy. And if so, some features of its working may coincide with the corresponding features of bourgeois democracy, recreating them in a new form. Moreover, some of the principles of the “proclamation” of bourgeois democracy are only truly implemented in the workers’ and peasants’ state. Also, direct participation of the masses in decisions of public affairs […] in the Soviet Republic, it is carried out in practice, thanks to the creation of a separate network of electoral cells and the unification of powers: responsibility […] ([…] only in the Soviet Republic, it is carried out due to replacement of officials and the same unification of powers); genuine public opinion controls all organs of power (bourgeois forgeries of public opinion disappear), etc.

We do not call to go back to bourgeois democracy, but forward to the expanded form of worker-peasant democracy. Only people infected with bureaucratic spirit may not understand that this is our goal, but authoritarian techniques are a temporary phenomenon, which is not the sole manifestation of a worker-peasant dictatorship.

By the way, the attraction of new layers to public work to replace the “exhausted” part of the proletarian avant-garde, presupposes the reduction of “command” methods and increase in public initiative of the masses. A class mobilization in the proletariat under current conditions can be created by moving towards a developed form of worker-peasant democracy.

What should be done to eliminate the main “shortcomings of the mechanism”.

The ways in which we must make this transition are as follows:

First of all, it is necessary to connect all Soviet agencies directly to the organizations of the working masses. Commissariats of foodstuffs and finance, first of all, should be “workerized” by involving proletarian organizations in their system and involving representatives of these organizations in decision making. This is how the “personal union” of Soviet bureaucracy and the proletariat is created.

But the position of Soviet officials should be radically changed as well. The number of emergency commissioners with extraordinary powers should be limited to a minimum. The rights, duties, and activities of the officials should be defined by precise norms. […] a Soviet republic may demand from them to fulfill their legal duties and refuse to fulfill their illegal demands. For their actions, especially for abuse of power, officials are responsible not only to their “department,” but also to elected bodies and the people’s court (it is best to arrange special tribunals for this purpose), to which every worker and peasant can summon them.

All bodies carrying out searches and arrests (in particular, emergency commissions) must be subordinate to the judicial power. It should be explicitly stated that the emergency commissions should be turned into a properly appointed (i.e. subordinated to the control of the court), criminal and political police, which should exist in the workers’ and peasants’ state until further development makes it possible to replace it with a nationwide people’s militia.

Both local Soviets and especially VTsIK (All-Russian Central Executive Committee) should become collegial institutions that discuss general norms and following policy measures, guide their implementation and indeed control their implementation. For this purpose, VTsIK may establish standing committees. It is necessary to reduce, and partially stop the concentration of legislative and executive powers within the narrow closed ministries–starting with the Presidium of VTsIK, the Council of People’s Commissars and departmental tops to the corresponding local cells. Uniting legislative and executive powers does not create arbitrariness and detachment from the masses only if the powers are united in the hands of experienced elected bodies.

The activities of all authorities should be controlled by the public opinion of workers and peasants. The meetings of collegial institutions should be public, open, and the commissariats should give reports on their work to VTsIK. All their work and the activities of individual officials should be constantly illuminated by this body of central power. The same shall apply to local councils. It is also clear that only a free discussion of all issues of public life in the press and at meetings leads to a firm ground for public discussion in elected institutions.

The workers’ and peasants’ public opinion and the petty-bourgeois parties.

Here again we hear the questions: So you are proposing universal freedom of the press, of assembly (and therefore of unions)? Does this not mean a return to bourgeois democracy? And further: isn’t it related to the return to the soviets of parties hostile to workers’ and peasants’ power? And isn’t it related to the change of the course of our policy, which is so heavily criticized by the Mensheviks?

And in any case, we do not call back to bourgeois democracy, but forward to the full implementation of workers’ and peasants’ democracy. First of all, the workers’ and peasants’ democracy provides the workers and peasants with a real basis for the free use of speech, press, and assembly in a union organization (the bourgeoisie is deprived of space for […] telegraphy and paper, and the possibility of any bribed campaigning is destroyed). As for the very use of these real opportunities, we take care to ensure that workers and peasants are able to freely express their opinions. For us, only their public opinion exists, but not that of the bourgeoisie and its parties. The bourgeoisie and its parties are dead; they do not exist.

So, who can express their opinion in the Soviet Republic and what can they say? Only parties and organizations whose representatives were sent by workers and peasants to their councils. Between them should be deployed, according to the number behind us of […]–premises, telegraph machines, and paper. At meetings and in the columns of newspapers, they shall substantiate the same views as those expressed in the councils.

Thus, we have indeed come to the question of which parties may be represented on the councils. Until recently, petty-bourgeois parties were expelled from the Soviets. Now they are in a semi-legal position there. We must say clearly and unequivocally that at this stage of development there is no need to remove from the Soviets and from free discussion, parties that do not call for a direct overthrow of Soviet power. It is also possible that we will come to grant this freedom to all parties that can have representation in the Soviets.

Since the balance of real forces has been confirmed in favor of the proletariat and the poor, since the Soviet state has been strengthened and established, freedom of the press and assembly for the petty-bourgeois parties represented in the Soviets is possible and necessary. The control of public opinion over the work of the Soviet authorities is thus expanding. In the chorus of public opinion, are heard the voices of backward politicians who express the opinion of the most backward and hardened layers of the petty-bourgeoisie. All the better: any clash of opinions is useful in the Soviet state because it has strengthened its existence. Variety makes it easier to find the right path quickly. As for gentlemen petty-bourgeois politicians, they are offered full opportunity to push for a change in general policy by influencing public opinion in a “soft parliamentary way” that they so praise. Only here public opinion is different and voters are different. But these voters, not worse, but better than parliamentary voters, can understand who is right and who is wrong.

As far as policy changes are concerned, allowing a minority to defend their opinions does not mean a change of course on the part of the majority. It only expresses the strengthening of the position of this majority. In addition, petty-bourgeois politicians and petty-bourgeois masses are “two big differences”. The overwhelming majority of the petty-bourgeois masses (peasants) followed the proletariat and its party and approved its policies. And this policy […] the party offered the petty-bourgeois masses through the head of people who wanted to speak on their behalf, but spoke only in the name of the kulaks and the bosses […]. Therefore, if we admit the lords of petty-bourgeois politicians to the Soviets, it does not mean that we “made peace with the petty-bourgeoisie” (we did not quarrel with it), and therefore it does not mean that we commit ourselves to any concessions to these lords.

Thus, the question of the content of Soviet politics is by no means predetermined by fallen defeats. This is a special question. But the forms of defining this policy are predetermined: it is managed by elected bodies; it is conducted by officials directly subordinate to these bodies, who give them permanent master reports; they are rightfully controlled by the public opinion of workers and peasants.

We think that if the Soviet Republic enters this path in the near future, the petty-bourgeois lords […] will have to testify bitterly that the Soviet Republic has survived another crisis unscathed. If this does not happen, the crisis will drag on, but it will still be resolved, and namely that is necessary. And the historical necessity will sooner or later declare and realize its rights. And the historical necessity is that the great and strong Soviet Republic grows and develops further, throwing off its skin, which has become tight for it.

8th Congress of the R.C.P.(B.) — SECOND MEETING

ORGANIZATIONAL SECTION

March 21st, morning, 1919

Original proceedings, pages 187-197:

The meeting opens at 11:10 a.m.

Chairperson: I declare the meeting open. Comrade Avanesov has a word for order.

Avanessov: To reduce the time, I would suggest connecting the last two questions and giving the speakers a little more time.

Chairman: Are there any objections? No. Is it convenient to amend the regulations in order to provide the co-rapporteur with 30 minutes and 10 minutes for the final word? Accepted.

Osinsky:

Comrades, our party program includes a clause that speaks of the struggle against the revival of bureaucracy. By stating that we have a revival of bureaucracy, I must begin my report. This revival of bureaucracy is what we have called the “minor” and sometimes the “major” shortcomings of the Soviet mechanism in newspapers and discussions all the time. How is it expressed? Critics dwelt very little on elucidating the causes of this phenomenon. It should be noted that in our Soviet activities, the work of open elected collegia1, for example, plenums of local Soviets, plenary sessions of the CEC [Central Executive Committee]2, meetings, etc. is dying down. At meetings where the prepared bills are voted upon, there is no discussion of these bills.

Then, the lively work of the masses in state-building has frozen in our country. Decision-making is concentrated in narrow collegia, which — we need to straightforwardly state — to a considerable extent are detached from the masses in a significant way. We now have all issues resolved in executive bodies, starting from the very top and ending with the very bottom. The development of personal politics should be attributed to the phenomenon just mentioned. I must say that two months ago Comrade Lenin raised the question in the Central Committee about the development of our personal policy. This is called, speaking the German language–“Zettelwirtschaft”–economy by means of notes. We have solved a lot of problems by notes of various commissars.3 On this basis, starting from the very top, from party comrades, a system is developed for resolving problems by one-on-one means and a personal conduct of business is being developed. From here a whole system of irregularities arises, which leads to the fact that we are intensely developing patronage for close people, protectionism, and, in parallel, abuse, bribery; and, in the end, especially in the provinces obvious outrages are committed by our senior, sometimes party, workers.

At present, the old party comrades have created a whole bureaucratic apparatus, built, in fact, on the old model. We have created an official hierarchy. When we made the demand of the commune state at the beginning of the revolution, this demand included the following provision: all officials must be elected and must be accountable to elected institutions. In fact, we now have a situation where the lower official, who acts in a province or county and is responsible to his commissariat, in most cases is not responsible to anyone. This explains to a large extent the outrages caused by the “people with mandates”, and despotism develops on this basis.

There’s an extreme development of paperwork. Entire groups of people gather who do nothing. And if our program is the so-called cheap government, then at the present time we can say that our government machine is extremely expensive. There are a lot of extra posts, they are paid all the time, and people who are registered as staff but to a large extent do nothing, eat bread for nothing and only increase clerical red tape. The question is, what is the reason for this? Two explanations are outlined in the draft of our program. On the one hand, it is indicated that the layer of advanced workers in Russia is unusually thin, while our state apparatus can be based only on this stratum of advanced workers. The new class state of the republic of workers and peasants should be based on personnel from the new classes that came to power–from the workers and the rural poor. Meanwhile, the layer of conscious representatives of these revolutionary classes is unusually thin. If this layer is thin, then the second layer is little cultivated due to the backwardness of our country. Then there is another main factor: under such circumstances, it is necessary to use the old bureaucratic apparatus, composed of the old workers of the former tsarist apparatus. As a result of this, all the old habits began to carry over to our institutions.

Such an explanation of the revival of bureaucracy is given by the program. Those two reasons, closely related to each other, which are indicated here, are undoubtedly very important, but not the only ones. There are other equally important reasons. We must reckon with the general situation in which our state-building is still taking place. Firstly, it takes place in a setting of acute civil war, and secondly, the construction of a new state mechanism was to be completed extremely quickly. Both required a military-style dictatorship. Our dictatorship acquired a military command character, we had to concentrate our powers in the hands of a small collegium, which was to quickly, without friction, discuss bills, etc. We had to quickly build a new state machine. Since the proletariat took power into its own hands, it needed to be consolidated by the creation of a solid apparatus, a solid state machine. Clearly, this could only be done if quick directives were given from the center. To a large extent this explains the phenomenon that we had to concentrate in the hands of a small collegium, sometimes even individuals, executive and legislative functions. This was supposed to strengthen the bureaucracy that is now beginning to penetrate us from the other end in the person of the old officials.

If we turn to measures to treat the shortcomings of the Soviet mechanism, then, taking into account the two kinds of reasons that I spoke about, we should outline a few other measures than those that are usually exhibited. The following question may arise: do these two reasons continue to have effect, that is, that we must quickly build the state apparatus and that we are at war? Of course, these reasons continue to operate, mainly the reason that comes down to the severity of the civil war. However, their action at some point begins to weaken. The civil war is weakening around the beginning of the winter of 18-19. It should be noted that in relation to the civil war, we had some change: namely, inside the country, the old state class was basically broken by the beginning of this winter, the bourgeoisie was defeated, it transferred forces to the outskirts, from where it is trying to send regiments that want to overthrow our power. But in the center this dominion is undermined, the bourgeoisie is broken, and the layer that supports it is also broken, such as the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia, from which vast detachments of the White Guards were recruited. Comrade Dzerzhinsky at the CEC factional meeting stated that at present we do not have the large kulaks of the White Guards, we have only scattered intelligentsia groups in the center of Russia, then the middle layer of clerks, various employees, etc. If they are not completely remade by us, then they are disorganized. The economic power has been taken away from the bourgeoisie, the main enterprises, banks, etc., have been taken away — in short, its keys to the economy, which are usually the keys of political power, have been taken away. This fact is important: there is no trace of the old state machine, the new state machine is basically laid down. In general, it turns out that we defeated our enemies within the country. We leveled all classes and even if they are not destroyed, we disorganized the enemy.

In such an environment, for us, the correct operation of the apparatus is a matter of great importance. If our apparatus is unable to cope with the tasks it faces, it can make it possible for these sectors of the population to oppose us not even because they will be counter-revolutionary, but simply because our apparatus will not serve them. We are mainly threatened by the fact that we are not coping with economic tasks. We defeated the bourgeoisie, but can we organize new production, feed and clothe the citizens of the Soviet Republic? That is the question. Because in this area we will not be able to cope with our task, we will be at risk of spontaneous indignation against us. Here it must be noted that the mass of peasant uprisings is explained by the outrages of the commissars of our provincial bureaucracy. Very often, the news of these revolts indicates that the peasants have nothing against the Soviet regime, but they rebel against the commissars who end up in the village. We need to seriously think about how to find ways to treat this deficiency. A transition is necessary from such forms when legislative and executive powers are concentrated in few hands to such forms when legislative and executive powers are exercised by the broadest possible masses. We cannot now proceed to the full, expanded form of the new democracy, to the workers ‘and peasants’ democracy, to that which is called the commune state. We cannot proceed because this is primarily hindered by the ongoing civil war inside the Soviet Republic, and, on the other hand, by an external onslaught. For a long time we will practice military command forms of the proletarian dictatorship. But at present, in order for us to have a stronger foundation within the country, so as not to incline the population against ourselves, we must expand the circle of those citizens who directly implement this dictatorship. We must involve at least the entire mass of the proletarian vanguard, if not the entire working class as a whole, if not the entire mass of workers and peasants in legislative, executive, and supervisory work. To do so, a number of concrete measures need to be taken to ensure that the power of government is transferred to the wider collegia chosen by the wider proletarian vanguard masses.

In addition, we need to take a number of different special measures against the revival of bureaucracy for the special reasons mentioned in the program. From these measures, I can clearly point out the following. First of all, it is necessary to start from the very top. At the top of our state apparatus there is an incredible parallelism, a repetition of institutions that do the same thing. For example, I now head the department of Soviet propaganda, which conducts international propaganda of the ideas of the Soviets and Soviet construction. In addition, at least 6-7 institutions are involved in this business, which absolutely cannot demarcate themselves from each other and interfere with each other all the time. I have given this example in order to go straight to the main one. First of all, there is parallelism in central government bodies. On the one hand, there is a Council of People’s Commissars, and on the other, there is a Presidium of the CEC, and their work largely coincides. Since the Presidium of the CEC is not only the Presidium that implements the decisions of the CEC or directs its meetings, it takes over the consideration of bills. On the other hand, the Council of People’s Commissars is considering the same bills. And neither the members of the CEC Presidium, nor the Council of People’s Commissars can say for sure where the powers of one body end and the powers of another begin. First of all, it is necessary to merge these two central government bodies into one. The question is which one to join to which: should the Presidium be attached to the Council of People’s Commissars or the Council of People’s Commissars to the Presidium? The Moscow Provincial Conference decided to add the Council of People’s Commissars to the Presidium. I am speaking on this issue not only on behalf of the provincial conference in Moscow, but also on behalf of the Ural delegation. At a joint meeting of these two delegations, it was decided that we should act differently: we must take the old name of the Council of People’s Commissars and attach the Presidium to the Council of Commissars.

In essence, there is no difference whatsoever, and there can be no serious objections to that. On the ground, the Executive Committee is at the same time the Presidium of the Council, the legislative body and the executive body. Parallelism will be reduced by this, and the legislative and executive work will be clarified. If we do this, then our people’s commissariats will turn into what we need, into what they should be according to the Constitution, but which really is not. They are constitutional departments of the CEC, but in fact there are also departments of the CEC, whose activities coincide with those of the former, and the commissariats are actually becoming independent. If the Council of Ministers merges with the CEC Presidium, it will be the first guarantee that the commissariats will be CEC departments. Similarly, various local authorities – financial, educational, etc. – must be departments of local councils.

Next is the second proposal. I mentioned it yesterday and today I repeat it in a very serious way and now I will prove that at the moment, in fact, if we keep in mind the Council of People’s Commissars, there is no single government. I had the honor of being a member of the Council of People’s Commissars in November, December and January 17-18. Then, the Council of People’s Commissars discussed the main issues of politics. If there was a conflict with the Romanian ambassador, he was arrested or a war was declared – all this was considered at a meeting of the Council of People’s Commissars. This is currently not observed. Comrade Sapronov mentioned that Chicherin’s note about the Princes’ Islands fell into the regions, as if from heaven. Comrade Zinoviev says it’s not the case. In fact, this is true in some respects, because according to Chicherin’s first answer, it seemed that we were accepting an agreement, but we would not accept the Princes’ Islands, that this was a provocative proposal. But it was accepted. And this answer was completely unexpected for local organizations: they were not prepared for this form of response. This answer turned out to be unexpected even for members of the collegium of the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, the institution that should consider foreign policy issues. The members of the board read this note in the newspapers, but did not take part in the discussion. Did the Council of People’s Commissars take part in this discussion? No. And not one of the major notes in the Council of People’s Commissars was considered. Now individual decrees are being considered there, they are being edited there, and some of the board members state that they have turned into an editorial commission. They do not rule the country, but consider decrees and resolve interagency tensions and disputes. There is no single government that governs politics in general. This situation needs to be changed.

Of course, there are no forms or prescriptions that can help the cause. At the beginning of the revolution, the situation was such that our government was a real government. And at this point, if the majority of the Central Committee members are members of the Council of People’s Commissars, the following advantages will be obtained. First, the Council of People’s Commissars will become a government in the full sense of the word. It will have to be in charge of policy at all times, as there will be the most senior political workers there. On the other hand, the Central Committee will always be in place and will not even have to meet to decide on individual issues, as these will be dealt with by the Council of People’s Commissars. And if it is necessary to solve more general issues, it will not be difficult to convene the Central Committee. Such a structure of the Council of People’s Commissars guarantees the existence of a real government, which is alive and working. On the other hand, there will really be a Central Committee. Against this, there may be objections that by doing so we will disrupt the business work of the Council of People’s Commissars. Nowadays, the Council of People’s Commissars consists exclusively of business people, and if not exclusively, then to a large extent, of people who understand political questions very poorly, but know very well their own departments. And it is necessary to understand, comrades, that this departmentalism does harm. If the government consists of business people, if it is a business cabinet, it is quite clear that everyone here will talk about the interests of their department and will argue about the boundaries of the competence of their agencies, and there will be no general political leadership. Typically the government is structured as follows: each agency should be headed by a responsible political head, and with him there are business fellow ministers. This is the case abroad, and it was also the case with us before. And thanks to this, the business work is not disturbed at all. All business commissars can be turned into deputy commissars. We will not lose anything from this, but we will acquire a real government, which we lack.

Chairperson: Your time is running out.

Osinsky: Then I will have to just read the theses. Here they are. (He reads.)

THESES ABOUT SOVIET CONSTRUCTION

Under the conditions of the civil war the apparatus of the new class state was built at an increased pace, the workers’ and peasants’ power still had to concentrate its legislative and executive powers in narrow and closed collegia (executive committees, bureaus, presidiums, etc.) or in the hands of individuals with unlimited powers. The need for such military command forms of proletarian dictatorship will not disappear completely until the victory of the international revolution. But now that the old state machine has been destroyed, the new one has been built, the old ruling classes and the production relations have been broken down, it is an opportunity to take a number of steps towards the proletarian class democracy, which is our goal in the field of state-building. Under these conditions, these steps consist of the broad involvement of the proletarian avant-garde in the legislation, management, and supervision. These steps will prevent the bureaucratic rigidity of the Soviet mechanism, revive its work, attract new cadres of workers and help to eliminate the spontaneous discontent of the masses with the shortcomings of the Soviet mechanism.

When we issued a decree on the emergency tax, then at the meeting of the CEC faction it turned out that no preparation had been done for the population. And the very same is true. Krestinsky admitted that it would have been more expedient if this issue had been widely discussed beforehand – then the masses would have been prepared and it would have been easier to implement it. Nowadays, even non-urgent draft laws are carried out without any preliminary preparation. In addition to measures to democratize the forms of proletarian dictatorship, it is necessary to take a number of special measures against the revival of bureaucracy. To this end, the Congress considers it necessary to implement the following provisions:

1) In order to fully unite and centralize legislative and executive activities, the Presidium of the Central Electoral Commission merges with the Council of People’s Commissars, which assumes all the functions of the Presidium. Existing people’s commissariats, in accordance with the requirements of the Constitution, become departments of the Central Electoral Commission, people’s commissariats are the heads of these departments and, at the same time, the members of the Presidium.

2) In order to eliminate this situation, when the Council of People’s Commissars has become a meeting of business commissars, which discusses individual decrees and does not actually direct the government policy as a whole, which leads to the strengthening of bureaucracy, it is necessary that as many members of the Central Committee of the party as possible should be part of the government.

3) In order to involve all CEC members in active work, the CEC composition is divided into sections corresponding to the departments. The sections are responsible for the preliminary review of decrees and major events of a fundamental nature that fall within the competence of the department.

4) As some people’s commissariats nowadays find themselves inclined to issue orders without discussion in the Council of People’s Commissars that contradict decrees and interfere with the competence of other central and local institutions, it is necessary to establish and implement a rule that no department has the right to issue principal and other particularly important decisions without discussion and approval by the Council of People’s Commissars.

5) The CEC plenum, being the supreme body of the Republic in the period between congresses and sitting at least twice a month, should take part in the legislation on the most important issues and in fact discuss and monitor the activity of the Council of People’s Commissars and departments of the All-Russian CEC.

6) Department estimates are discussed in detail in the financial section of the CEC and are approved by the plenary for each department separately.

7) Elections to the CEC at the Congress of Soviets are held only after all the candidates nominated separately are discussed in the party factions, and none of the members of the Presidium of the previous CEC should chair the election sessions. The list of members of the Communist faction of the CEC is approved by the Party Central Committee. After the approval of the lists by the Congress, they are announced at the last session of the Congress and are immediately published.

8) In order to establish a close connection between the CEC and the organizations of working masses, the majority of the CEC and its sections shall consist of employees of professional, cooperative, cultural, and educational organizations, etc.

9) In order to properly prepare and implement new actions, decrees and orders of general principle, except for the most urgent ones, should be discussed in advance in the sections and plenum of the CEC, reported in the abstracts to the local executive committees for review and considered in the press, as well as at meetings of workers’ organizations.

10) In order to save revolutionary forces and centralize local power, all executive committees of the city except for the executive committees of the capital cities and industrial centers are abolished, merging with provincial and district executive committees, to which all local power is transferred in the period between congresses.

11) Local executive committees shall organize departments and sections accordingly to departments and sections*. Each department is headed by a member of the executive committee. Members of the executive committee must be employees of local territorial-production cells. Plenums of local councils should take part in the discussion of the most important cases and supervise the activity of the executive committee.

(* Apparently, a word is missing “[of the] All-Russian Central Executive Committee”. -Ed.)4

12) As the People’s Commissariats currently seek to subordinate local departments to their direct influence, separate them from the executive committees, appoint their own heads of departments and members of the boards, it is necessary to restore and confirm the provision of the Constitution that all local departments are subordinate to and controlled by the executive committees, that the heads of departments, subdivisions, members of boards and other responsible persons are elected by the councils, congresses and their executive committees. Only local and higher executive committees and the Council of People’s Commissars have the right to withdraw the elected persons.

In order to establish proper relations between the central and local authorities, an exact separation of powers should be worked out and fixed by law. In matters of national importance, local executive committees should be agents of the CEC and its presidium. All decrees and orders of the Central Authority are mandatory for executive committees. At the same time, local executive committees should exercise the widest right of local self-government.

13) In order to establish permanent relations between the Soviet bodies and working organizations, to constantly monitor the activities of the Soviet institutions by broad layers of the working class, members of sections related to professional, cooperative, cultural and educational organizations and cells should make regular reports on the activities of plenums, departments, and sections in which they participated. Heads of departments shall submit such reports to specially convened district workers and peasant conferences.

14) Special administrative and judicial departments shall be established in all executive committees in order to establish the real responsibility of officials and provide the public with a real opportunity to pursue officials who violate decrees and commit abuses. Collegia of departments are elected by the congresses and cannot be members of other departments. These departments have the right, upon complaints from the public, to overturn improper orders of officials, to remove officials who have committed offences, and to bring them to trial.

15) In view of the current abnormal tendency of the centers to establish separate local branch offices, which escape from the control of local executive committees, it must be established that local executive committees form a single office for all their departments. Loans granted by the centers to the relevant local departments are transferred to the account of the executive committee, which in turn has no right to delay and change the nature of the loans without special permission from the center.

16) In view of the apparent desire of the Revolutionary Military Council, individual headquarters, even individual commissioners to declare martial law without the consent of the executive committees, it is necessary to leave the right to declare martial law outside the front only to the executive committees and the Council of People’s Commissars.

The basic norms of martial law and the conditions under which it can be extended should be elaborated by the CEC in the near future.

17) Since the existing outdated division of the country into provinces and counties prevents the proper establishment of central and local government, it is urgent to develop and implement a new division based on the tendency of territories to production centers.