Jonah Martell lays out a twelve-step program for the Democratic Socialists of America to pursue a path of independent working-class politics.

Cheer up, comrades! It has been a sorrowful year for all of us, but the whole world has taken a beating—we’re hardly special. We will always have choices to make, strategies to explore, and opportunities to pursue. In this piece, I will do my best to illuminate some of them.

We can transform our political prospects. But first we will have to transform ourselves. It is pointless to “keep fighting the good fight” if that means pounding on the same brick wall forever. We must rethink old assumptions and learn some new tricks. If we retreat into isolated local projects or blindly “follow the leader,” we set the stage for another defeat.

Remember the Sanders campaign? Those months seem like a distant memory now. Bernie Sanders played by the rules of the Democratic Party, and those rules squashed him. Yet we have the power to write our own rulebook—not just by breaking with the Democrats, but by inventing a completely new way of doing politics. It is time to move past the obvious insights. Democrats suck; they are treating progressives unfairly; it is still a relief that Trump got fired. To do better next time, we must ask ourselves more difficult questions. The first one is very simple: who is “we?”

Who Are You?

Nearly every political argument invokes a “we,” a common group that should mobilize around something. Although this is useful for persuasive purposes, it can also muddy the waters. In the real world, there is never just one “we” that any of us belong to—no single collective agent. Readers of this article are presumably part of many “we’s.”

Several examples come to mind. There is the George Floyd protest movement. There is also Bernie World: the massive network of people who supported the Sanders campaign. And many of us feel a certain kinship with all left-leaning people in America—with our friends who want some kind of welfare state, even if they lack an explicit political ideology.

Then there is a much smaller “we”: the American socialist movement. People who own the word “socialism” and take it seriously, without needing a “democratic” disclaimer in front (most of us are even fine with the c-word). We clump around explicitly socialist organizations—most often the Democratic Socialists of America—and we use the dictionary definitions. We actually want common ownership of the means of production and a new political system to make it possible.

Socialists are a small but growing minority of the U.S. population. How should socialists handle being in a minority? One option is to embrace it, to turn inward and form angry little echo chambers that achieve nothing. Another is to bow to outside forces, watering down our beliefs in the name of “progressive coalition-building.” Both of these solutions fall short. There is nothing wrong with being in a minority, especially when your side has unique insights on how society works. What’s important is to be an outward-looking minority—a minority with a genuine desire for growth and a clearheaded awareness of its surroundings.

Where Are We?

One tempting idea is that the American Left is finished. With Trump out of office, the masses will become complacent, apathy will reign, and there will be no more appetite for political change. In such bleak times, this pessimism is understandable, but it’s also wrong.

Total nihilism about our prospects puts far too much faith in Joe Biden and the Democratic Party. The crisis in this country runs deeper than Trump. It began before Trump and will continue long after him. The public may want a return to normalcy, but that is just a short-term impulse. Biden’s party will be governing in the middle of a global pandemic and an economic recession. To govern alone, they will have to pull off an extraordinary political surgery: winning a Senate majority of one, voting unanimously to reform the filibuster, adding new states, and then packing the Supreme Court to keep their legislation viable.

Judging by their track record, are the Democrats up to this task? Are they capable of such ruthless political discipline? And even if they do accomplish it, will their leadership be ready to push through major reforms to help America’s struggling working class?

Perhaps Obama could make a few phone calls and threaten a drone strike on Joe Manchin. Otherwise, they will be governing at the feet of Mitch McConnell. Remember him, the Kentucky boy who looks like a turtle? That’s the man who will be holding Joe Biden accountable, not progressives. The GOP controls the Senate. It now controls the Supreme Court. It has ample weapons to impose a wingnut regime on America without Trump in office. Perhaps that is why they are refusing to wage an all-out war over Biden’s victory.

There will be no “bipartisan” healing, only stagnation and decay. When discontent resurfaces, multiple forces on the Left (not to mention the Right) will pounce to take advantage of it. One force to be reckoned with is Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and the rest of the left-wing Democrats in Congress. Because they will be locked out of Biden’s administration, they have nowhere to go but the pulpit. Their party is already eager to marginalize them, and they know the score. The planet is burning. Millions of us have no healthcare in the middle of a pandemic. Roe v. Wade may well be overturned, making abortion illegal for millions overnight and sparking massive upheaval. Every social gain of the past fifty years stands at the mercy of the Supreme Court.

Left-wing Democrats will have to change their strategy. Will they do so effectively? No one knows, and ordinary rank and file socialists should not rely on it. They are embedded in a coalition that prevents them from building a viable constituency. Our responsibility is to develop a more independent approach to politics, with or without their help.

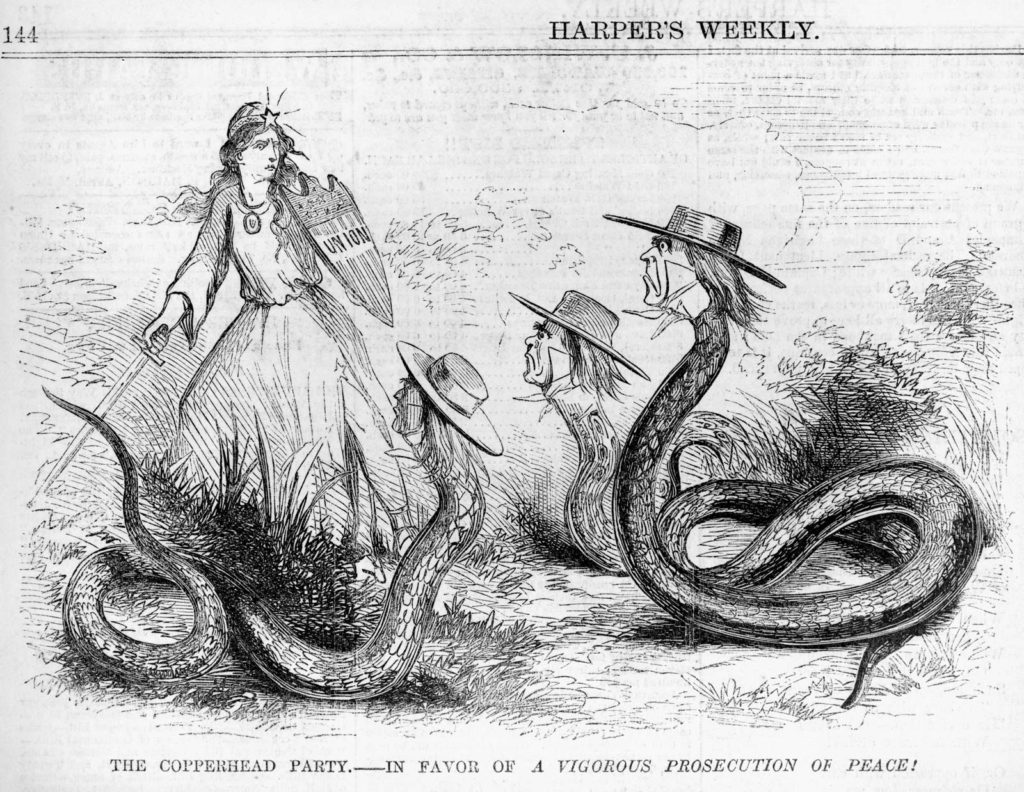

To understand why, let us talk about redbaiting. It worked this year, both on the Left and the liberals (particularly in Miami). Socialism has a powerful appeal among downwardly mobile young people who escaped their elders’ Cold War indoctrination. For a majority of Americans, however, it remains a dirty word. The Democrats stoked that base when they tarred Bernie as a shill for Castro. Then Trump took up where they left off, tarring Biden as a shill for Bernie, AOC, and a communist plot to destroy America. He and his party made a bet that even the most ridiculous lies would send the Right marching off to Valhalla. They bet right.

Thanks in part to red-baiting (not to mention race-baiting, jingoism, coddling evangelicals, and actually running an energetic campaign), Trump’s coalition turned out with millions more than they had in 2016. The Democrats lost seats in the House and didn’t win the Senate. Now the neoliberals are furiously blaming the Left. Representative Abigail Spanberger (D-Va.) has been particularly frustrated with her neoliberal colleagues for not repressing us hard enough. In a conference call shortly after Election Day, the former CIA officer had this to say:

“We have to commit to not saying the words “defund the police” ever again,” she said. “We have to not use the words ‘socialist’ or ‘socialism’ ever again.”

She may well be right. Censoring those slogans would be a smart tactical move for her party (not ours). But the Representative forgets three things:

1) Socialists are here to stay and will not be shutting up.

2) Left Democrats like Bernie worked tirelessly to turn out their constituencies for Biden. Despite the Right’s hatred of them, they played a crucial role in Biden’s victory.

3) Red-baiting targeted the Establishment’s weaknesses—not just ours.

That third point is counterintuitive, so it deserves some further context. Once again, the Democrats nominated an establishment candidate who set popular expectations as low as he possibly could. Why not fill the empty vessel? It made perfect sense for Trump and his allies to turn boring Joe Biden into a sinister communist puppet. The move served three basic purposes: stoke their right-wing base, pit the Democrats against their progressive wing, and avoid having to debate Biden directly because Donald Trump is an idiot.

Debating Boogeyman Bernie was easy enough, but had Real Bernie been the nominee, the dynamic would have changed in some very interesting ways. Sanders excels at something that is invaluable for all political leaders: incisive messaging. Instead of promising nothing, he would have countered Trump’s red-baiting head-on by aggressively selling his ideas: “You’re damn right I support Medicare for All and let me tell you why!” Whatever the results on Election Day, his base would have emerged with hardened convictions and itching for a fight.

A moot point of course: the Bernie constituency did not harden. Instead, it was defeated, co-opted, and now discarded, left to wallow in uncertainty about its future. Bernie lost because the Establishment rigged the primary—not with mail-in ballots and computer hacks, but with fear: fear of losing to Trump. Fear that Bernie accepted from the outset by promising his loyalty to any nominee and justifying his entire campaign by claiming to be America’s Best Trump Remover. Biden crushed that sales pitch the moment he cruised in with an orchestrated wave of big-name endorsements, signaling to all uncertain voters that the party apparatus was his. How could an open hijacker like Bernie be the Unity Candidate? The loyal crew rallied behind its captain and threw the pirate overboard.

Sold one-by-one, his policies were wildly popular, but bundling them together with a big red bow was too hard a sell for Democratic voters who feared Trump above all else. When Bernie lost the primary, he lost his podium as well. He spent the rest of the election shunted off in a corner, working quietly for Biden’s coalition to “save America” from total meltdown. There was nowhere left to go on the path he had set for himself.

How did that coalition treat him? Bernie wanted Medicare for All. The DNC Platform Committee would not even accept a universal program for children. In 1998, Bill Clinton called for lowering the Medicare eligibility age to 55. In 2020, Biden said “lower it to 60,” framing it as a generous concession to Bernie’s eager young whippersnappers. When Bernie delegates pushed for a move back to Clinton’s original proposal, the Committee shot that down too.

Medicare is for Seniors Only, and Biden has been quite firm on that principle. Nor was his public option a genuine concession. His campaign was happy to paste it on the website, but Biden played it down the instant Trump held his feet to the fire, claiming that it would only be a Medicaid-style program for the destitute.1

The American Left is being buried in coalitions that treat us like dirt. We beg them, appease them, and submit to their abuse. Then they still fail, despite all our efforts to prevent it, and each failure deepens our dependency on them. For decades, we have been hopelessly addicted to Democrats.

Let 2020 be the final relapse. We must be our own captains and build our own ship: a self-assured, self-reliant movement with no divided loyalties. A fearless movement powered by millions who cannot be cowed or manipulated. Millions who know exactly what we stand for; who are sold on both our policies and the big red bow that ties them together.

An independent, socialist, working-class party.

Who Will Build the Ship?

Such tired old words! They are usually where reflection ends, because they are infinitely harder to make real.

Will the Squad build the Ship? Will Omar, Tlaib, Pressley, Ocasio-Cortez, and the rest who won their primaries this year form a Democratic Socialist Party? Before socialists rush to take orders from them, the Squad’s track record deserves a partial review. They have:

-

- Firmly backed Medicare for All (all of them).

- Voted for a $2.7 trillion-dollar Pentagon budget (AOC, Tlaib).

- Endorsed Bernie Sanders (AOC, Omar, Tlaib).

- Endorsed Elizabeth Warren (Pressley).

- Held a sit-in at Nancy Pelosi’s office (AOC).

- Called Nancy Pelosi “Mama Bear” (AOC).

- Called for defunding the police (AOC).

- Held a photo-op with the NYPD (AOC).

- Fired her chief of staff for annoying Democrats (AOC).

- Slammed the Democratic Party as incompetent (AOC).

Suspend all moral judgments. Just ask from a distance: are these the actions of a disciplined socialist movement with a clear political strategy? Or are they the actions of a loose, informal circle of left-wing Democrats?

It is the latter, of course. Just like Bernie, members of the Squad are grappling with divided loyalties, balancing their genuine desire for progress with their obligations to a party that wants none of it. There has been much talk in DSA of launching a “dirty break”: having socialists run within Democratic primaries and one day splitting off to form a party of their own. But there is no evidence that anyone in the Squad has ambitions to do this. Unlike Bernie, they have spent their entire political careers working within the Democratic Party. Even if they do have secret plans, ordinary socialists are not privy to them and will have no say in how they play out.

DSA has thoroughly confused itself by viewing the Squad as its rightful leaders. A clear majority of DSA members want to chart a course away from the Democrats, but the Squad’s theory of change is based on “winning the soul” of their party. This is quite different from our mission to build an independent socialist movement.

If the Squad will not build the ship, then what about organized labor? If we stay patient and work hard within the unions, could they eventually toughen up to create an American Labor Party? Perhaps—but they will have us waiting for quite a while. For over eighty years the U.S. labor movement has functioned as an appendage of the Democratic Party. It has millions of members, but they are demoralized, dominated by stagnant leadership, and suffering from decades of decline. The Left certainly needs to rebuild labor, but trying to do so as isolated individuals is a vain abdication of responsibility. The Democrats have the labor movement in a political stranglehold, and to break it we must create a political alternative. Many times in history, it has been a left party that organizes and revitalizes the unions, rather than the other way around. Nor are labor-based parties guaranteed to be friendly to socialists—the purge of Jeremy Corbyn and the British Labour Left should give pause to would-be American Laborites. Enough waiting based on hypotheticals. The time for independent politics is now.

If we need an independent party now, then what should it look like? One option is to cast the net as wide as we possibly can. Throw the s-word out and join with every left-leaning person we can find to form a broad-based progressive party. The party could appeal on just a few policies that are already highly popular, like Medicare for All, and de-emphasize other issues that “divide us.”

It’s a tempting idea. Ditching socialism could take the heat off our backs and make growth much easier in the short term. There is already an organization that is trying to do this: the Movement for a People’s Party. Led by former Bernie staffer Nick Brana, it is determined to set up a “new nationally-viable progressive party.” It has recruited tens of thousands of supporters and an impressive lineup of high-profile speakers, from Marianne Williamson to Jesse Ventura. Running on a platform loosely modeled on that of Bernie’s 2016 campaign, it hopes to flip congressional seats in 2022 and win the presidency in 2024.

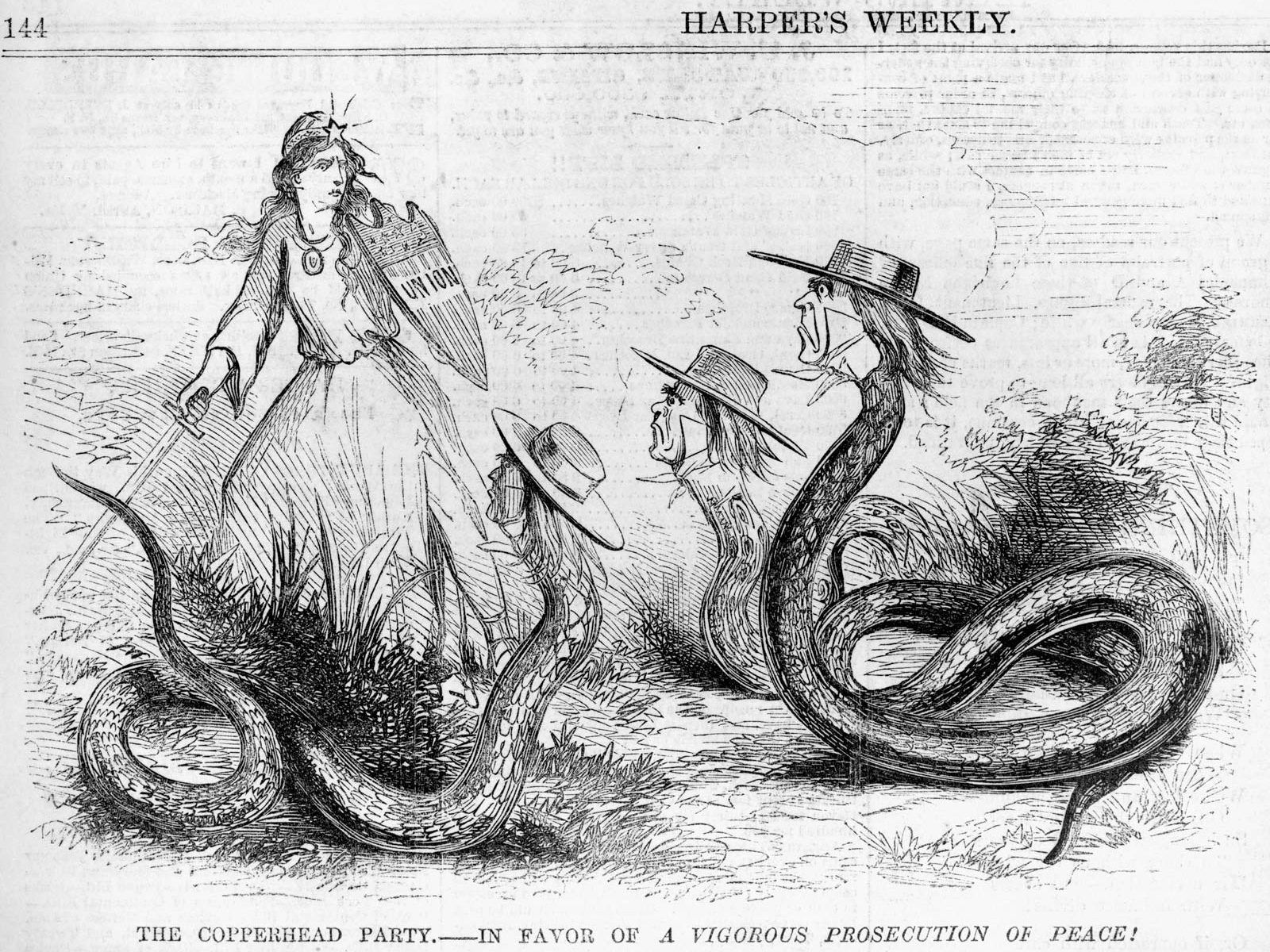

Although MPP’s ambition is admirable, the recent track record of “left populism” does not bode well for them. Populist coalitions boom and bust; they rise to power only to implement austerity; they speak in simplistic terms of “the People” and “the Elite” that impede more sophisticated class-based analyses. Their frantic rush for the presidency is quite unwise, as is their desire to conjure up an instant majority. Socialists would do well to remember the fate of America’s original Populist Party: cooptation in 1896 by a Democratic presidential candidate who adopted their demand for free coinage of silver.

Marxist political strategist Mike Macnair describes this impatient approach to politics as “conning the working class into power.” Karl Marx had similar warnings to his contemporaries in 1850:

[The faction opposing us regards] not the real conditions but a mere effort of will as the driving force of the revolution. Whereas we say to the workers: ‘You will have to go through 15, 20, 50 years of civil wars and national struggles not only to bring about a change in society but also to change yourselves, and prepare yourselves for the exercise of political power.’

Socialists should be gearing up for this long-term political struggle. We see the obstacles in front of us in a way that catch-all “progressives” cannot. Progressives hold a powerless but accepted niche within the American political system. It is easy for them to cheerfully dream of “taking back our democracy” and “advancing the American experiment.” Socialists have much weaker roots. Constantly derided as un-American, they are driven to question the dominant culture and the entire political system.

This political system is explicitly designed to “restrain the democratic spirit.” The president is not elected by popular vote. The Senate, with total control over cabinet and judicial appointments, vastly overrepresents conservative white voters, and its members serve staggered six-year terms. This is to say nothing of the Supreme Court, whose members serve for life and claim the right to strike down any legislation as they see fit.

The add-ons are helpful as well. Ballot access laws prop up an artificial two-party system, barring all third parties from meaningfully contesting elections. Millions of felons are disenfranchised. Gerrymandering and voter suppression are rampant. Virtually all elections are in single-member districts—winner-take-all.

“But the Founding Fathers intended it this way!” the conservatives screech when pressed for any progressive reform. “You can’t just change it on a whim!”

Meanwhile, they impose their own changes. They pack the courts, purge the voter rolls, and impose right-wing minority rule on the entire country. The Democratic Party will continue to submit to it for years to come because it is equally loyal to this tired Old Regime.

What is needed is not just a break with the Democrats, but a complete break in our way of conceptualizing political power. Will socialists continue to campaign for catch-all progressives, for left Democrats and marginal third parties? Or will we introduce something completely new and unprecedented to American politics—something that challenges not just the rules but the institutions that make them?

There will be no victory for the Left within the established constitutional order. It was designed to keep uppity leftists out of power. Conservatives know this full well. We will never win if we play by their rules. Our job is to develop a coherent strategy to attack their deliberately incoherent political system. A strategy based on incisive messaging, political independence, and a national struggle for power.

Just to be clear: from this point on, when I say “we” I mean DSA. For all its flaws, it is the flagship organization for American socialists. Where its competitors have three or four-digit memberships, its rolls will soon break 100,000. It is the ideal place to hammer out some kind of future for ourselves.

No individual can do it alone. But just to get the ball rolling, I would propose the following:

A TWELVE STEP PROGRAM FOR SOCIALISTS

(To Break Our Addiction to Democrats)

1) Declare political independence.

Remember what Joe Biden said at the first debate to counter Trump’s idiotic redbaiting. He said “I am the Democratic Party.”Don’t hate him! It was true, and it was actually quite clever of Joe. He was leading a messy coalition and he stepped up to assert responsibility for it. With those words, he wiped out the Bernie movement and made it crystal clear what the Democratic Party is about.

Now, remember how Bernie countered his own redbaiters when his campaign was just getting started. He gave a speech about “what democratic socialism means to me.” Do you see the difference here? One man is speaking assertively about an entire political coalition. The other is speaking on behalf of himself to humanize the s-word and make it less intimidating. But in doing so, he is stripping it of any standardized definition.

Is socialism an organized political movement or is it a slogan, a vague personal philosophy? Right now it is mostly the latter in the United States. Popular understandings of the term range from “equality” to “government ownership” to “talking to people, being social … getting along with people.”

If socialism is no more than a slogan, perhaps we should simply abandon it. The entire point of sloganeering is to popularize unpopular ideas. When the slogan alienates people and has no substance, it is useless.

It’s not quite that simple, of course. As conservatives love to say, we can’t erase our past, and picking a feel-good label for ourselves will not necessarily protect us. The Right will always be pinning the red bow on anything left of Mussolini. Just ask Podemos (and Joe Biden)!

Moreover, socialism is useful because it appeals to a critical target audience: young, downwardly mobile, working-class people who are already skeptical of American capitalism. Anyone can claim to be a progressive, from Maoists to Nancy Pelosi. Socialism is a knife that cuts us apart from the crowd; it has already captured the public’s attention. We just need to make sure that we cut ourselves into an organized political constituency and not a rebellious fashion trend.

DSA should act less like Bernie and more like Joe. It should step up and say, “DSA is the Socialist Movement.” When asked what socialism is, it should give a coherent definition. I will not presume to have a full answer here, but we should be clear that socialism is a mission to bring freedom and democracy to the working class—and that mission will require regime change. Moreover, because most self-professed socialists in America are also communists, perhaps we should be more straightforward about that when asked. A classless, stateless, communist society is our end goal—give or take a few generations.

That is how DSA should define itself publicly. It should also change the way it describes itself to members. It could put out a statement, even if it is completely internal, announcing that DSA considers itself an independent socialist party and expects members to conduct themselves accordingly. It will not have legal status as a party, but that doesn’t matter. Many American socialists, from Seth Ackerman to Howie Hawkins, have acknowledged the need for flexibility on this question. Because state governments dictate the structure of legally recognized parties, we should simply reject their regulatory frameworks and define for ourselves what a party is. Given the public’s understandable impulse to dismiss conventional third parties, we could continue to refer to ourselves officially as “DSA,” “the Socialist Movement,” or anything similar. Our actions will cement our political independence, not the formality of sticking the p-word in our official title.

There is nothing particularly misleading about this (if leaving out the p-word is opportunistic, then so was Rosa Luxemburg’s party). From a Marxist perspective, a communist party is a movement—a structured, organized, revolutionary political movement.2 Framing the party in these terms is therefore perfectly honest and acceptable. It would also subvert the shallow liberal conception of movements as flash mobs and Twitter hashtags.

All of these maneuvers may seem pretentious and overbearing, but they are necessary. The Right and Center have no qualms about defining socialism for the public. They define it as “misery and destitution.” Nor are the Left Democrats afraid to advance vague, meandering definitions that leave the Right howling and the fence-sitters completely unconvinced.

The momentum is with DSA. Even Trotskyist sects acknowledge this by routinely imploring DSA to form a new party that they can “affiliate” with. We have the power to step up and assert collective responsibility for the American socialist movement. It’s us, the Right, or the wavering politicians. Let there be no more talk about “What Democratic Socialism Means to Me.” From now on, the phrase should be “What the Socialist Movement Demands.”

2) Hold annual conventions.

This is a short point. For years DSA has held conventions on a biannual basis. Today that will not be enough. The United States has become rather unstable; conditions can change in a heartbeat and we will have to adapt to them quickly. To keep up with the pace of events, we should hold conventions every year, constantly reevaluating our platform and strategy.

3) Form statewide organizations.

What is the mourning cry of a defeated progressive? It’s this:

“Oh well. I’ll just get involved in local politics. That’s where the real change happens anyway.”

A noble thought; every one of us has had it at some point. Unfortunately, it reflects an unconscious peasant mentality. Giving up on large-scale political change, the progressive returns to their village to do what little they can.

“I would never challenge His Majesty the King. Better to cultivate my little garden.”

A garden is not an island. American cities have more autonomy than their counterparts in many other countries, but that is not saying much. State and federal policies shape every aspect of local government. They prohibit cities from requiring paid sick leave for workers. They require them to accept fracking within their boundaries. They force towns to base their speed limits on pre-existing traffic flows, ratcheting up car speeds and slaughtering pedestrians.

When we confine ourselves to local politics, we become functionaries of the capitalist state. We also play into the reactionary old American idea that all problems are best solved locally, that large-scale social programs can never be trusted. We must build an opposition to the capitalist state at every level, and that means creating strong regional organizations. A DSA caucus called the Collective Power Network raised this point quite effectively in 2019. What they forgot to fully address is the appropriate scale for these regional entities: the state level. The Republicans and Democrats have their state parties. So should we.

“But that’s modeling ourselves on the bourgeois state!” cry the anarchists.

No, it is laying siege to the state. Our state chapters will run on simple majoritarian lines; they will not have Senates and Supreme Courts and Governors with veto power. What they will have is the capacity to run statewide campaigns and contest state policies that impact the lives of working-class people. They will also encourage local chapters to collaborate, improve outreach outside the big cities, and alleviate some of the burden on the national organization—which has been charged with the impossible task of managing 235 locals.

Admittedly, there are some sparsely populated states with very few DSA chapters, and in these areas statewide organization could be impractical, at least in the short term. A United Dakota, North and South, might make sense for DSA’s purposes. Fusing states for tactical reasons is perfectly acceptable; the only inadvisable move would be creating regions that cut states into multiple pieces, preventing unified statewide campaigns.

Although a national organizing drive would be invaluable, DSA’s local groups can take the initiative right now. There is already an easy, underutilized process to integrate DSA chapters. According to DSA’s constitution, just two or more locals may petition to form a statewide organization, pending approval by the National Political Committee and a majority of locals within the state. A similar process is available for locals seeking to form regional organizations.

4) Nurture a committed membership base.

What does it mean to be a DSA member? One impulse is to make it an extremely demanding, prestigious title—the Navy SEALs of activism. In his classic text on Marxist strategy What Is to Be Done?, Vladimir Lenin called for a disciplined party of professional revolutionaries. Should American socialists aim for the same thing?

No, because for Lenin, ruthless discipline was a necessary evil, not a virtue. Russian revolutionaries operated in a Tsarist police state where the slightest misstep invited discovery, police raids, and mass arrests. The United States is in many ways shockingly repressive, but it is not a tsarist autocracy. In our context, socialists have much more to learn from socialist parties outside the Russian Empire that maintained more open membership structures. They cultivated mass movements—millions strong—to build a vibrant oppositional culture against capitalism. They offered social services, opened libraries and grocery stores, set up cycling clubs, choir societies, picnics and social outings. Germany and Austria offer intriguing historical examples. Today, Bolivian socialists are doing similar inspirational work.

But we don’t just have to look abroad. There are non-socialist, all-American organizations in the United States that show us what dedicated membership looks like. In 2015 the National Rifle Association had 5 million dues-paying members, and nearly 15 million Americans identified with the organization whether they paid dues or not. It cultivates group identity with a wide array of community services—including an official magazine, concealed carry insurance, firearms training for millions, and opportunities to join its 125,000-strong army of training instructors.

Yes, the NRA is a reactionary, racist organization, riddled with corruption and now in decline. We still have much to learn from it (not to mention the churches that, for better or worse, provide millions of Americans with social services and community life). There is thrilling potential for secular left-wing institution-building, from tenant unions and worker centers to art circles and sports clubs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hiking clubs and other outdoor activities could be a particularly powerful social service, breaking people out of their isolation and alleviating mental health burdens.

These ideas go beyond feel-good charity work. They are structured party programs, designed to build a massive support base that can be deployed for confrontational political action. They will cost quite a bit of cash.

This brings us to a crucially important, non-negotiable element of dedicated membership: monthly dues. Dues are the life-blood of a mass movement; they foster group identity, incentivize recruitment, and provide the party with a steady, predictable stream of revenue.

But what about low-income, working-class people? Couldn’t dues make the movement inaccessible to them?

Quite the opposite. Dues can be tapered based on income, and studies show that the poor give a greater portion of their income to charity than the rich. Asking people to pay a steady monthly fee is much more reasonable than bombarding them with fundraising emails that endlessly scream “give, give, give!” Nor is volunteer work a more accessible basis for membership than dues. Time is money, and every hour that a person spends with us is an hour that they could have spent working an extra shift or taking care of their children.

Dues allow us to make reasonable asks of others and avoid activist burnout. We don’t guilt-trip the single parent working two jobs or the exhausted volunteer with mental health burdens. We say: “Don’t worry. Take a break as long as you need to. Just help us stay afloat and keep paying your dues.” There will always be varying levels of involvement, and not all of us will be red Navy SEALs. Anyone who supports our mission, votes for our candidates, and pays their dues deserves to be called a member of the Socialist Movement.

We must still take measures to promote membership engagement. Only active members should get a vote in party affairs, and we should encourage all members to come to at least a few key events every year. All chapters need a point person to welcome newcomers and help them forge connections with other members, preventing locals from becoming insular social clubs. We will offer engaging, freewheeling education groups to introduce new members to our politics. All of this is necessary to make ourselves an “outward-looking minority.”

A key task for DSA will be to reevaluate and standardize its dues structure and perhaps ask a little more of its members. DSA membership is worth more than the current 67-cent monthly minimum. Rather than dismantling dues, as some anarchist-leaning caucuses have suggested, we must embrace and celebrate them as the foundation of a self-reliant movement.

5) Adopt a nationwide political platform.

DSA is currently working on a platform to synthesize its political demands. This is a very exciting development and an important step to assert ourselves as a distinct force in American politics. We should develop a truly revolutionary program that, if fully implemented, would hand power to our country’s working class and place society on a socialist transition out of capitalism. We must repeal every law that props up the two-party cartel and eliminate every institution that denies us an authentic majoritarian democracy. Abolish the Senate, abolish the Electoral College, and smash the Supreme Court—send Brett Kavanaugh and all his colleagues packing.

So that working people can fully participate in political life, we should also demand unimpeded labor rights, a massive reduction in working hours, and a comprehensive welfare state that would make Scandinavians blush. Create programs to reduce the power of bureaucrats and give ordinary workers administrative skills; promote worker self-management in all industries. Place the commanding heights of the economy under public ownership and rapidly phase out fossil fuel production. Dismantle the repressive arms of the state: abolish the military and policing as we know it and replace both with a democratically-accountable popular militia. This last point will be challenging yet still indispensable. We must transform the empty demand for “police abolition” into appealing slogans and substantive policy proposals.

We have our work cut out for us: we must develop a comprehensive program and find ways to promote it to a mass audience. Even so, we will not be working in isolation. We can learn from the history of past revolutions and from the platforms of our predecessors in socialist parties across the world.

Is this project too arrogant? Will we alienate ordinary people if we draft a comprehensive platform instead of a short list of popular demands? If we treat the platform as an inalterable holy text, then yes. If we leave it open to regular revision and use it as part of our political education process, then no. The intuitive red-meat demands are indispensable: we should certainly continue to advance Medicare for All and other programs that improve the quality of life for the working class. But we will never achieve those demands unless we attack the political order that is making them unachievable. Our platform must point towards a break with the capitalist state and fight for an authentic working-class democracy. We need to build a constituency that believes in the legitimacy of that fight. A “political revolution” will not be enough to defeat America’s reactionary Old Regime. No, that will require a break of epoch-making proportions, a world-historic social revolution.

6) Run dedicated organizers for office.

Many “revolutionary” organizations have an impulse to steer clear of electoral politics. Stumping for office might seem to legitimize a system we want to overturn, so why do it?

The obvious answer is that the state has tremendous power and it already has legitimacy for most people. It will be here for quite a while. Retreating from the political arena does nothing to stop that. More importantly, electoral work done right can erode the legitimacy of the system and help us win the support of millions. Electoral campaigns can be used as a bully pulpit to attack the system and demand a new political order. Lenin did this, the German socialists did this, and so can we.

Electoral politics can also embolden and merge with the combative worker and tenant struggles that often capture leftists’ attention. Bernie Sanders taught us that when he personally manned picket lines, and West Virginia teachers showed it when they drew inspiration from Bernie to go on strike.

What we need to avoid is getting sucked into another abusive coalition like Bernie. The key to this is recognizing the Democratic Party as the irredeemable zombie that it is. Bernie tried to heal the zombie and he got bitten hard. Instead of collaborating with the neoliberals, we should strive for total independence and self-sufficiency in our electoral bids. DSA could train and run gifted organizers who promise to coordinate their campaigns, accept the party platform, and vote as one bloc when elected. Candidates would be entirely free to personally disagree with elements of the platform and push for changes through internal party discussion. In the halls of power, however, they would be expected to act as one team, with accountability to the entire membership movement.

We see a preview of this approach in New York, where DSA recently ran a victorious slate of insurgent socialist candidates. If we hardened and expanded this approach nationwide, it would put us to the left of even the Squad–whose members have hesitated to endorse other primary challengers after winning office themselves.

We would not align with the Democrats. Instead, wherever they won office, our candidates would form an independent socialist caucus. Both parties would be welcome to meet with us to discuss policy–at the opposite end of a long negotiating table.

This approach would not win us much love from either side. Legislative committee appointments would be sparing or nonexistent, but that is okay. Establishment politicians may hammer us as useless backbenchers, but we would simply counter by pointing out how useless they are, listing off all the ways they have betrayed their constituents in the past. We would make use of our extra free time by serving as relentless advocates for the communities that they have ignored, publicizing socialist policy proposals, providing constituent services, and assisting local organizing projects. To show their dedication, our elected officials would refuse to take more than a typical working-class salary and donate the rest to our community programs.

The value of electoral work done right cannot be understated. Many “revolutionary” leftists begrudgingly accept its necessity as a type of “propaganda,” but what passes for propaganda on the Left is often just obnoxious megaphone yammering. It would be better to describe it as a form of organizing, as outreach to carve out a constituency that believes in our cause.

One popular idea in DSA is that candidates should always “run to win.” It is correct that we should be running professional campaigns, with talented candidates who truly want to come out victorious. If we finish with single-digit results, that is probably a sign that we ran our campaign poorly and need to reevaluate our strategy. However, it’s important to remember that the path to victory can be longer than one election cycle, and an honorable defeat can still build the movement. Cori Bush did not win her initial campaign in 2018, but now she is headed to Congress to join the Squad. Nor did Bernie Sanders win his first independent House bid in 1988–that took a second try in 1990. If we abandon every “loser” the moment they fall short, we may end up discarding capable leaders who still have future potential.

In the long run, our goal should be to run candidates for every office possible, even where we cannot win. This boosts our visibility as a national political movement and will help us extend our presence outside the large urban centers. Like Bernie, we must eagerly engage with rural, small-town, and Republican-leaning voters. If we abstain for fear of losing, we will never be able to build a truly national constituency.

7) Stop endorsing outside the party.

Once we have a training program for this new approach to electoral work, we must wind down the faucet of endorsements. DSA should focus all of its energy, messaging, and resources on promoting its own candidates: active, committed members who promise to uphold the platform. The only exception would be strategic collaboration with candidates from other independent left parties. Electoral pacts to avoid competition in certain districts may occasionally be necessary.

Cutting off endorsements may seem like a sectarian move, but it is perfectly reasonable. AOC and other Squad members are sparing with their primary endorsements; they have not mounted a massive assault against their Democratic colleagues. They have pragmatic obligations to attend to, and so do we. We should pour all our energy into cultivating talented candidates who are embedded in our organization and committed to building an independent movement. When we endorse candidates who are not directly accountable to our membership, we muddy the waters on what DSA stands for.

None of this means that we will run around viciously denouncing left Democrats and other progressive candidates. They are not responsible for this crisis. We will sometimes criticize their political strategy, but our fiery speeches will be reserved for the ghouls who actually hold the cards: Biden, McConnell, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and so on. When our rabble-rousing socialist backbenchers take up their seats, they may want to collaborate with the major parties from time to time, and left Democrats could end up playing a valuable role as mediators. And who knows? Some of them may be impressed by our new brand of politics and join our ranks. The goal is not to be sectarian. We are just stepping up to become self-reliant, to make our own independent mark on the world.

8) Choose ballot lines at the state level.

Should we keep running our candidates in Democratic primaries, or should we rush to set up our own ballot lines?

Every state has its unique convoluted rules, so there’s no easy answer to this question. That’s the point. Our system is designed to encourage incoherent thinking, to fragment and divide power to make majoritarian politics impossible. When future schoolteachers describe the decline and fall of the United States, they will point to its divided political system, the fifty jurisdictions marked out on a map. The children will laugh out loud and ask how it lasted so long.

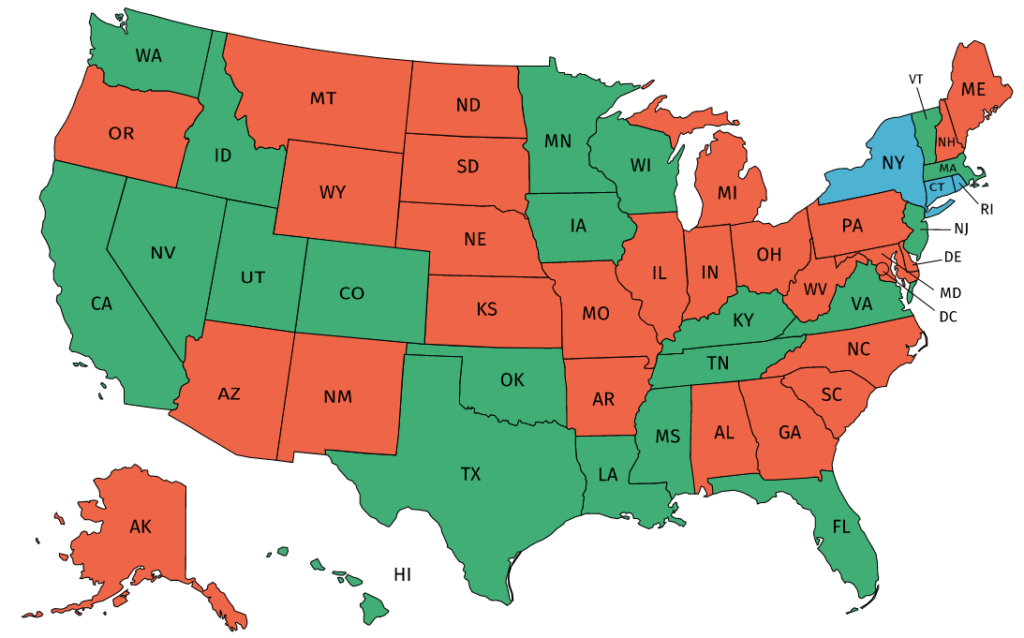

The states have had third parties running like gerbils on a wheel, focusing all their energy on petition gathering and hopeless presidential campaigns (required to secure ballot access). Even staunch third party advocates like Hawkins know that it’s time to break the wheel and try something new. Perhaps we should ditch the ballot access crusades and just run nominal independents. That would allow us to stop running top-heavy presidential tickets, to be more discriminating about which elections we target. An interesting map comes together with a glance at state ballot access laws for House candidates:

Green states are reasonably friendly to independent bids. They require the same number of petition signatures as major-party candidates. Or, if the requirement is unequal, the total number of signatures needed is still 1,000 or fewer. Red states have clearly unequal requirements, although they are not necessarily insurmountable. Blue states have very different procedures for major party and independent candidates and are difficult to compare directly.

It’s clear that there are weak spots. California, Texas, and Florida all have equitable access for independents. Why run Democrats for the House in any of those easy states?

Once we have dedicated state-level organizations, they will be able to make these judgment calls decisively. In New Jersey, where only 100 signatures are required for independent House bids and party machines brazenly rig their primaries, “clean break now” is an excellent approach.

In Georgia, the rules for independents are extremely inhospitable and primaries are open to voters from any party. There, it would make sense to antagonize the Democrats with a large slate of DSA primary insurgents. For the sake of clear messaging, ballot line choices should generally be consistent across the entire state. We would confuse primary voters if we ran an independent in one congressional district, a Democrat in the one next door, and a Republican for a county office that overlaps both districts.

Even when we run in a party primary, we should still run our candidates on the DSA platform and be committed to political independence. The line could be this: “I’m running as a Democrat. It was the only way to get on the ballot. Once I’m elected, I’ll renounce my party affiliation and serve with the Socialist Independents.”

Off they will go to join the rest of our rabble-rousing backbenchers. Under this framework, the “dirty break” is no longer some vague goal that we banish to the distant future. It is something that we do every time we win an election, enraging both capitalist parties. Call it the filthy break – perhaps we will even run Socialist Republicans in Montana! Eventually, both parties should be expected to crack down and pass laws to close up their primaries. Hopefully, we will already have a mass constituency by that point.

Right now, DSA prioritizes Democratic bids and neglects independent campaigns. That order should be reversed. Clean independent bids should always be prioritized, wherever we can realistically get a couple strong campaigns on the ballot. They establish our independence and make it clear to the public that we are not Democrats—that we are out to break the two-party system.

“But you’ll never win as an independent!” some will protest. “I did!” Bernie Sanders would have replied in 1990. It’s an uphill battle, but not an impossible one.

Vote-splitting is another valid concern. Unfortunately, it is a fact of life in any winner-take-all election. It happens in Democratic primaries (peace among worlds, Liz!). Even the fear of vote-splitting can do great damage to insurgent primary campaigns. NYC-DSA learned that the hard way when self-appointed socialist kingmaker Sean McElwee released a poll to deliberately tank Samelys López’s congressional bid, claiming that she would split the vote and put a conservative Democrat in office.

Vote-splitting will happen, and we will have to find ways to reduce the public’s fear of it. Establishing ourselves as a viable force worth splitting the vote for will be one important step. We will have to pick our campaigns carefully in the beginning to build capacity and establish a political foothold. But from the very outset, we must make it clear that we are intent on further expansion. The Socialist Movement has the right to run its candidates across the board, just like any other political party.

9) Target the House of Representatives.

What made the Bernie movement so powerful, so terrifying, so utterly invigorating for its participants? It was a national struggle for power.

That point deserves to be repeated: participation in the Bernie movement was participation in a national struggle for power. In the campaign’s words, it was a mission to “defeat Donald Trump and transform America.”

America alienates the U.S. left. We are not nationalists; we are not patriots. We reject much of the dominant culture. This makes it difficult for us to conceive of politics as a nationally coordinated struggle. It is much easier to think in terms of local organizing or international solidarity. Both are crucial projects. The working class has no country; the socialist movement must be international, and our work is hopeless without effective local organizers on the ground.

But the best thing we can do for our local organizers is to integrate them into a coordinated movement for transformative change. The best thing that we can do to foster internationalism is build a real, unified revolutionary organization in America, a powerful socialist movement that can give inspiration to others around the world.

If we play our hand well, our next national struggle will be different from Bernie’s in some important ways. We will be more ambitious, more independent, and less deferential to established institutions. Instead of trying to redeem the Democratic Party, we will oppose it head-on alongside the GOP. Instead of seeking a “political revolution” within the capitalist state, we will call for a world-historic revolution and a new political order: an authentic working-class democracy. How can we integrate our union work, tenant struggles, and electoral campaigns into this grand vision? Do we run another presidential campaign?

Not in 2024. Barring something completely unforeseen, we will not have the numbers, organization, and high-profile leaders necessary to mount an interesting presidential bid. We would waste precious volunteer hours collecting signatures and then come out with 1% of the vote. It would be hopping right back on the gerbil wheel. Once we have a larger base, we can contest the presidency (on a platform of abolishing the presidency by revolution).

But our main target should be the House of Representatives. It is a federal institution, elected every two years in local districts that are small enough for us to realistically target. We can run a National Slate of candidates, from Washington to Florida, from Michigan to Maine, and talk it up in our stump speeches. We can use the House as a national soapbox to publicize our demands. We will be speaking to America coast-to-coast, raising our public profile and giving a boost to all of our state and local candidates. The House is the most important electoral institution for us to contest in the years to come.

We can begin in the urban deep blue districts that Democrats have dominated, plus some red district bids to expand our repertoire. This will offer political choice to one-party districts that have had none for years, giving us a chance to establish viability. Then, as quickly as we can, we should strive to contest all 434 congressional seats, forcing a messy national referendum on our political demands every two years.

The next three points could be among the most important demands.

10) Organize for electoral reform.

We must demand an end to the two-party system. We should fight for easy ballot access for all political parties, ranked-choice voting and multi-member electoral districts, proportional representation in Congress, and anything else that gives working-class people more choice at the ballot box. In the wake of the 2020 Census and the GOP’s electoral fraud witch-hunt, a new wave of gerrymandering and voter suppression will be arriving very soon. In this political climate, our campaigns for electoral reform should be connected to wider efforts to protect voting rights, such as citizen redistricting panels and automatic voter registration.

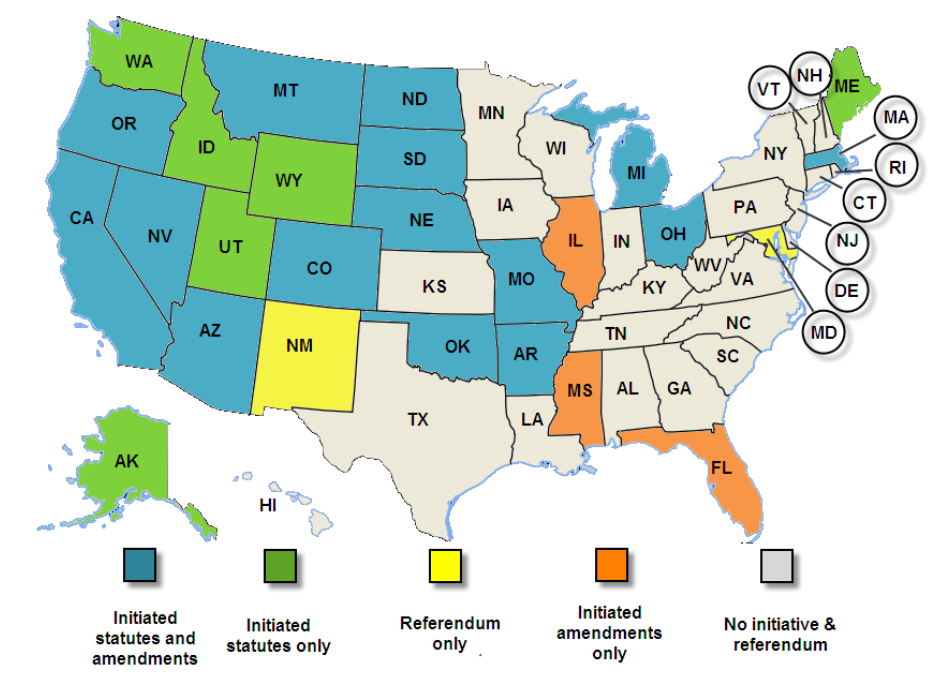

We must integrate these demands and advance them with incisive slogans, playing on popular antipathy to entrenched politicians and the two-party system. Many states have ballot initiative processes that we could use to our advantage, mobilizing voters to pass electoral reforms at the ballot box. Such campaigns have already been mounted by nonpartisan groups, successfully in Michigan, Maine, and Alaska (and unsuccessfully in Massachusetts). Although petition circulation requirements are often arduous, a volunteer-powered mass movement may well be able to blast through the obstacles.

Electoral reform campaigns are one more way to establish our political independence. They will also help us establish that socialists are champions of a richer democracy (and that the capitalist parties are not!).

11) Shoot down war budgets.

The U.S. spends more on its military than the next ten countries combined. Trillion-dollar slush funds, poured into graft, arms manufacturers, right-wing dictatorships, and bloody imperialistic ventures all over the world. That is no secret; it is common knowledge to tens of millions of Americans.

We cut ourselves apart through total noncooperation. We should refuse to vote for any spending bill that pours one more penny into the bloated military, police departments, or any other repressive capitalist institution.

If we do this, will we cause endless government shutdowns? Unlikely. The Republicans and Democrats will pass their “bipartisan” budgets right over our heads. Drop a heavy boulder into a creek, and the water finds its way around it. But it gives us something to stand on to capture public attention, to erode the legitimacy of an institution that Americans are taught to view as sacrosanct.

12) Demand a new constitution.

What is a demand that would truly set us apart, that would bring the Right’s worst nightmares to life?

Demand a New Union. A new constitution, developed by mass popular participation. Not an Article V convention. No state-by-state ratification. An accessible process that everyone within the borders of the United States can contribute to, combining grassroots direct democracy with a National Constituent Assembly. The final ratification would be by national referendum—a simple majority vote.

In a free society, everyone gets a say in the social contract that they live under. That is not what happened when the current constitution was written. Women had no say; black people had no say; working-class people had no say. We demand that the living, breathing people of the United States be given the right to determine its future. We demand a constitution that guarantees real democracy, majority rule, housing, healthcare—economic rights.

We will be quite clear about the additional reforms that we would advocate throughout the process: abolish the Senate, abolish the presidency, abolish the Supreme Court. All power to an expanded, improved, democratized House of Representatives.

“We demand that Congress initiate this process, but if it does not, the people have a right to do so themselves.”

There is a legitimate argument to be made that the Constitution can be legally amended by referendum. This deserves an article of its own, and we should certainly invoke constitutional law as needed. Of course, none of our opponents will take our arguments too seriously. Revolutions make their own laws, and what we demand is nothing less than a world-historic revolution against the forces of Old America.

Let the Trumpers fume over the socialist plot to destroy the Constitution. Let the liberals lecture us about the dangers of norm erosion. Obama can start an NGO to educate young people about the beauty of our institutions and the farsighted wisdom of our Founding Fathers. We alienate most people at first, but we strike a chord with a sizable minority. And every year, we build it out, leaning into every crisis, growing, until finally something snaps.

That is the last point. To recap all twelve:

-

- Declare political independence.

- Hold annual conventions.

- Form statewide organizations.

- Cultivate a committed membership base.

- Adopt a nationwide political platform.

- Run dedicated organizers for office.

- Stop endorsing outside the party.

- Choose ballot lines at the state level.

- Target the House of Representatives.

- Agitate for electoral reform.

- Shoot down war budgets.

- Demand a new constitution.

Perhaps these suggestions are unrealistic. They may demand too much of a small organization like DSA; they may overestimate the potential of the era we are living in. But even if we try them and fail, at least we will fail on our own terms, in a more instructive way than ever before. Progressive reform movements rise and fall, both inside and outside the Democratic Party. For decades they have led us to defeat, cooptation, and humiliation. Many generations of the American Left have grown exhausted with this ritual, but instead of building a real alternative, the disenchanted vent their frustration with performative action. Endless rallies, megaphone chants, and radical posturing take us nowhere. Localist organizing projects “feel good,” but they completely lose sight of the national struggle for power.

–Trump to Biden on the Left

What we need are performative restraint and political aggression. Independent politics is not a distant end goal; it is not something we earn after working hard enough for the Democratic coalition. It is the heart of the socialist project, the foundation of effective revolutionary struggle, and something that we ought to start doing right now. The time has come to forge a new strategy that draws on the best of the Bernie campaign and everything that came before it. A fearless strategy, hardheaded yet still principled, that never loses sight of the real end goal: a world-historic, working-class revolution in the USA.

And the goal of this piece is to contribute some starting points.