Daniel Lazare writes on the US Constitution, its inherent contradictions, and why socialists should oppose it.

In order to theorize the United States, socialists must theorize the US Constitution.

By “theorize,” we mean a theoretical analysis not of certain parts, but of the phenomenon as a whole. Rather than focusing exclusively on racism, sexism, and the like, as leftists are wont to do, this means coming to grips with “USA-ness” itself – why it arose, what it means, how it managed to conquer much of North America in a matter of decades, and why it has played such an outsized role in world history ever since.

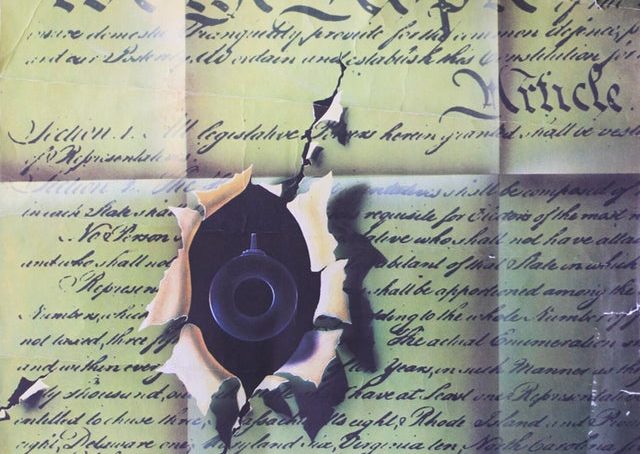

The same goes for the US Constitution. Law reviews and poli-sci journals overflow with articles about this or that clause or theory of interpretation. But attempts to grapple with the Constitution in its entirety are rare. Why did eighteenth-century patriots attach so much importance to a written document? Why has it proved so durable? Why do increasingly undemocratic features such as a lifetime Supreme Court or a Senate based on equal state representation draw so little attention? To be sure, articles about the Electoral College have grown common since Republicans used it to steal the presidency in December 2000. But once it becomes clear that reform is impossible within current constitutional confines – which is indeed the case – everyone goes back to sleep.

So what are we to make of a plan of government that seemingly “disappears” its own shortcomings? Is it simply that Americans are too busy or lazy to care? Or is passive acceptance part of a social contract that is more contradictory and ambiguous than people realize?

What, moreover, does this have to do with socialism? Is Marxism above such local concerns when it comes to the international capitalist crisis? Or, given capitalism’s multi-dimensional quality (which is to say the fact that it is not just an economic system but a political and social one as well), shouldn’t Marxists recognize that the US constitutional crisis is part and parcel of the larger capitalist breakdown and that it is impossible to understand one without the other?

The answer is obvious. Capitalism is concrete. It arises out of real institutions and real societies. We can’t understand it as a whole unless we understand its various components as a whole and determine how they figure in the larger process.

Is the Constitution rational?

The logical place to start is with the document itself. The Constitution (which originally consisted of just 4,300 words but has since grown to around 7,500) consists of a Preamble, seven articles, plus twenty-seven amendments. Article I deals with Congress, II with the presidency, III with the federal judiciary, IV with the states, V with the amending process, while VI contains the all-important supremacy clause declaring that, once adopted, the document “shall be the supreme law of the land.” Article VII, finally, outlines how the ratification process is to proceed.

Since the Constitution says it’s the law of the land, and since law must be rational, the implication is that the document as a whole must be rational as well, meaning that the various pieces must hang together in a logical manner that makes sense. Every legal textbook and every last judicial decision assumes this to be the case; indeed, it would be hard to imagine a society basing itself on laws that it frankly admits are nonsense.

But how do we know this is the case? The Preamble, for instance, seems to advance a straight-forward theory of popular sovereignty in which “we the people” can do whatever they want “in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility,” and so forth. Article VII drives the point home even more forcefully since it is clearly at odds with the Articles of Confederation, the plan of government approved by all thirteen states in 1781 and still the law of the land when the framers gathered in Philadelphia six years later. The reason it’s at odds is simple: where the Articles of Confederation stipulate that any constitutional change must be approved by all thirteen states (“…nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made … unless such alteration be agreed to in a congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every state”), Article VII’s “establishment clause” says that the new constitutional alteration will be considered valid when ratified by just nine.

Since this was contrary to the Articles of Confederation, this means that the Constitution was illegal at the time it was drafted, a problem it promptly rectified via the miracle of self-legalization. It’s like telling a cop who’s pulled you over for speeding not to bother writing a ticket because you’ve just changed the law in your favor. But what would be absurd for an individual is the opposite for a sovereign people as a whole. Just as “we the people” can make any law they want in order to improve their circumstances, they’re free to disregard any existing law for the same reason.

To paraphrase Richard Nixon: if the people do it, that means it’s legal. This is the definition of popular sovereignty— people are over the law rather than under it and hence legally unbounded when it comes to their own self-advancement. So the Preamble states in combination with Article VII. But the rest of the Constitution goes on to say something very different. Article I establishes a complex legislative process whose purpose is clearly to limit the people’s decision-making abilities. Article II establishes an equally roundabout way of electing presidents. Article III says that federal judges may “hold their offices during good behavior,” which effectively means for life even if the people want to remove them mid-stream.

How can a supposedly sovereign people submit to restrictions on their own power? Finally, there is the amending clause set forth in Article V, which imposes the most astonishing restriction of all. It says that the people cannot change so much as a comma without the approval of two-thirds of each house of Congress plus three-fourths of the states. Back when there were just thirteen states, this meant that four states representing as little as ten percent of the population could veto any constitutional reform sought by the other ninety percent. Today, it means that thirteen states representing as little as 4.4 percent can veto any reform sought by the other 95.6.

What is even more remarkable is that Article V goes on to lay out two instances in which the people’s power disappears entirely. The first says that “no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article,” which deal with the slave trade. The second says that “no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.”Even if every last American agreed that the slave trade should be abolished immediately, in other words, the Constitution says they couldn’t do so for a full twenty years after ratification. Even if the overwhelming majority agreed that a Senate based on equal state representation was intolerable affront to democracy, the Constitution says they can’t alter it in the slightest without the unanimous agreement of all fifty states, which effectively makes it impossible. It thus renders the people powerless as well – not for twenty years but for as long as the Constitution remains in effect.

How can the Constitution declare the people to be simultaneously omnipotent and impotent? This would appear to be the very definition of incoherence. The rightwing Federalist Society claims to believe in “natural law, the idea of law as founded upon reason and logic and not merely the ipse dixit [unproven assertion] of a given power.”1 But if the Constitution is not founded on reason, as it clearly isn’t, then isn’t this a case of seeing logic where it doesn’t exist?

Of course, it’s not just the Federalist Society but the ruling class in general, who feel this way. All schools of constitutional analysis claim to interpret the Constitution in meaningful ways. Hence, all assume that a kernel of meaning lies at the core. But since we know that the opposite is true, that liberal society can be described as a gigantic conspiracy aimed at pulling the wool over the people’s eyes regarding the essential meaninglessness of their founding document. The result is a classic blind spot concerning a flaw that bourgeois society cannot allow itself to see so that it may continue to function.

Such contradictions are hardly limited to the US. To the contrary, liberal society in general rests on such blind spots. Classic English liberalism, for example, prides itself on the rule of law, political moderation, slow and steady reform, and so forth. “I hear you’ve had a revolution,” Harry Truman remarked to Britain’s George VI following Labor’s sweeping victory in the 1945 parliamentary elections. “Oh no,” the king replied, “we don’t have those here.” Revolutions were for lesser people like the Russians or French, not for a civilized nation like the Brits. Yet, British moderation is in fact a product of a century of turmoil beginning with the English Civil War in 1642 and ending with the Battle of Culloden, the result of an attempted takeover by the vanquished Stuart dynasty, in 1746. England had to go through the fire before Victorian legalism could be achieved. It had to be immoderate in order to become moderate and then forget that it had ever been immoderate at all.

The US Constitution accomplishes the same trick in virtually the same breath. First, it invokes popular sovereignty but then cancels it, so that “we the people” can submit to a rule of law beyond democratic control – and all in the name of democracy no less. It performs the operation so neatly that bourgeois legal scholars forget that popular sovereignty existed in the first place.

So is this our theory of the US Constitution, i.e. that of a self-denying system of government whose purpose is to blind the people to its own contradictions? One that declares the people to be sovereign in theory while denying it in fact? The answer is not quite. First, we’ve got to examine what purpose this blind spot serves.

Political playing field or instrument of class rule?

E.P. Thompson closed his 1975 study, Whigs and Hunters, an examination of eighteenth-century politics and law, with a swipe at a “highly schematic Marxism” that holds that “the rule of law is only another mask for the rule of a class” and that therefore “[t]he revolutionary can have no interest in law, unless as a phenomenon of ruling-class power and hypocrisy; it should be his aim simply to overthrow it.” Against this sort of “structural reductionism,” Thompson argued in favor of a more supple mode of analysis:

…in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the law had been less an instrument of class power than a central arena of conflict. In the course of conflict, the law itself had been changed; inherited by the eighteenth-century gentry, this changed law was, literally, central to their whole purchase upon power and upon the means of life.… What had been devised by men of property as a defense against arbitrary power could be turned into service as an apologia for property in the face of the propertyless. And the apologia was serviceable up to a point: for these “propertyless” … comprised multitudes of men and women who themselves enjoyed, in fact, petty property rights or agrarian use-rights whose definition was inconceivable without the forms of law.2

Rather than merely imposing class rule, law achieved hegemony by laying out a political playing field with room for everyone to take part. While obviously benefitting the high and mighty, it offered a measure of protection for the “petty property rights or agrarian use-rights” of those below. The poor thus ended up trusting in the law as well, thereby rendering its hegemony all the more complete. The situation was much the same in British North America, where, if anything, everyone had more of a stake since property was more widespread – not counting slaves and Native Americans, that is. Consequently, New England wound up even more legalistic than Old England back home.

Since travel was difficult from north to south, politico-legal arenas of conflict tended to unfold within colonial lines. The War of Independence changed this by drawing the ex-colonies into a common polity, while the Constitution fairly revolutionized it by deepening political integration in general. Moreover, it continually turned up the heat by trying to accomplish several tasks at once: create a powerful central government while ensuring states’ rights, establish an unprecedented level of national democracy while entrenching slavery even further than the British, etc. The elaborate compromises that the framers carved out in 1787 ended up both infuriating and enlivening all sides, which is why the entire structure exploded in civil war just 74 years later.

While the Constitution summoned up and cancelled popular sovereignty in practically the same breath, it offered a consolation prize in the form of a powerful new politico-legal system in which eighty percent of the population could take part. The new politics were vast and dramatic, especially once slavery emerged as a major point of contention with the Missouri Compromise in 1820. The people were still not sovereign in the strict sense, but they were politically alive in a way they never had been before. In France, the people created constitution after constitution after 1789. In America, the Constitution created the people by taking scattered seaboard communities and molding them into something approaching a unified polity.

Structuring politics

But not only did the Constitution create a new politico-legal arena, it shaped it.

Of the 85 Federalist Papers written by Madison, Hamilton, and John Jay from October 1787 to May 1788, the most frequently cited is the tenth, with good reason. In it, Madison takes aim at the “factious spirit” that he says is forever the bane of stable government and comes up with both a diagnosis and a cure.

First the diagnosis: “From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.”

Hence, it not only different degrees of property that lead to conflict, but different kinds of – “[a] landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests,” as the Tenth Federalist puts it. “The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation,” Madison adds, “and involves the spirit of party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of the government.” So how can we make sure that all these interests and factions behave themselves for the good of larger society?

Reading between the lines, it is evident what Madison is up to. Not only is he concerned about struggles between rich and poor, but between different economic sectors, slave-owning planters on one hand and bankers, merchants, and incipient manufacturers on the other. Since he feels it would be unjust to allow one sector to violate another, his concern is how to keep them separate but equal.

Hence his cure: Madison admits that in the rough and tumble of daily politics, the task is not easy. Ordinarily, he says,

…the most numerous party, or, in other words, the most powerful faction must be expected to prevail. Shall domestic manufactures be encouraged, and in what degree, by restrictions on foreign manufactures … are questions which would be differently decided by the landed and the manufacturing classes, and probably by neither with a sole regard to justice and the public good.

What Madison understands as bullying seems inevitable, but Madison hoped to prevent it via the miracle of complexity, i.e. the division of the polity into so many sub-units and sub-sub-units that political movements will wind up dashing themselves upon the rocks. As the Tenth Federalist notes:

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular states, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other states. A religious sect may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it must secure the national councils against any danger from that source. A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire state.

And, of course, the wickedest and most improper project of all would be the abolition of slavery since it would strike at the Southern landed interest’s very existence. Therefore, the goal was to scatter and confuse the abolitionists. This was the purpose of non-sovereign sovereignty: to prevent the movement from spreading from state to state and thus coming together as a mighty whole.

This explains both the success and failure of the Civil War. Despite Madison’s efforts, abolitionism succeeded in crossing some state lines. But it didn’t succeed in crossing the Mason-Dixon Line thanks to various pro-slavery provisions that the Constitution had put in place: states’ rights; a three-fifths clause in Article I providing slaveholding states with as many twenty-five extra seats in the House of Representatives and twenty-five extra votes in the Electoral College; a southern-controlled Supreme Court that ruled in Dred Scott that blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect”; a Senate in which slaveholding states were guaranteed parity, and, finally, an amending clause that gave the South an unchallengeable veto over any and all constitutional changes.

Since the Constitution rendered slavery secure within its southern redoubt, the only way around the problem was to suspend the Constitution and launch a revolutionary war aimed ultimately at expropriating the plantocracy. Even though they would never admit it, this is precisely what northern politicians set out to do.

But once “normal” politics resumed after Appomattox, northern politicians restored the Constitution in full since it had established the only politico-legal arena of struggle they had ever known. Rather than venture deeper into revolutionary waters, they opted almost instinctively to stick with the existing framework. To be sure, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments abolished slavery and federalized citizenship in 1865-70, which is why Popular Frontists like the historian Eric Foner extoll the supposedly radical changes they wrought. But, in fact, such reforms rapidly disappeared within the constitutional morass. Former slaves sank into neo-slavery while the notion that they “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect” once again became the law of the land throughout the old Confederacy. Roughly one American in fifty had died, yet the only thing the Civil War accomplished was to eliminate southern secession as a political threat.

Such are the results of democratic self-nullification.

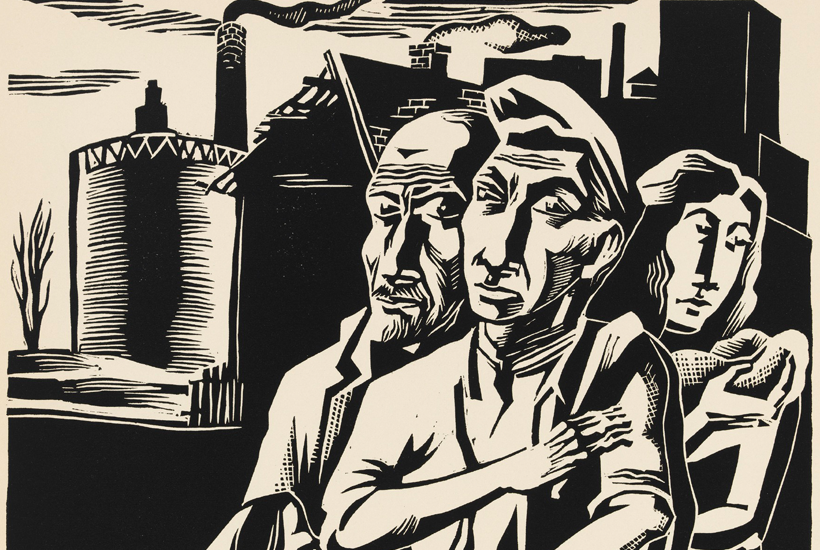

The circularity of American politics

The ups and downs of the socialist movement that emerged after the Civil War are too numerous to cover in this essay. But it suffices to say that the Constitution “over-determined” its failure by scattering the movement’s energies and preventing it from coming together in a single mighty mass.3 It did so by entrenching racism, (one of the SP’s best-selling pamphlets was a broadside against the “ni*ger equality” that bosses sought to impose by forcing whites to work side by side with blacks)4, and fairly mandating massive repression. Officials called in the state or federal troops to break some five hundred strikes between 1877 and 1903, cementing US labor history as the bloodiest and most violent of any industrial nation outside of czarist Russia.5

The constitutional recrystallization of the post-Civil period resulted in a curious paradox: class unity at the top and disaggregation below. In 1902, the leader of a group of anthracite coal-mine owners declared: “…the rights and interests of the laboring men will be protected and cared for – not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in his infinite wisdom has given control of the property interests of this country.” Sociologist Michael Mann observes: “…no other national capitalist class behaved with quite such righteous solidarity.” Yet workers, split along racial, ethnic, religious, and geographical lines, did the opposite. Socialism requires “a sense of totality,” Mann adds, yet it was precisely a totalizing working-class perspective that the Madisonian constitution was designed to prevent.6

Which brings us to … Islam. A footnote that Frederick Engels included in an essay he wrote about the history of religion in 1894 turns out to be oddly relevant to America’s current plight:

Islam is a religion adapted to Orientals, especially Arabs, i.e. on one hand to townsmen engaged in trade and industry, on the other to nomadic Bedouins. Therein lies, however, the embryo of a periodically recurring collision. The townspeople grow rich, luxurious and lax in the observation of the “law.” The Bedouins, poor and hence of strict morals, contemplate with envy and covetousness these riches and pleasures. Then they unite under a prophet, a Mahdi, to chastise the apostates and restore the observation of the ritual and the true faith and to appropriate in recompense the treasures of the renegades. In a hundred years they are naturally in the same position as the renegades were: a new purge of the faith is required, a new Mahdi arises and the game starts again from the beginning. This is what happened from the conquest campaigns of the African Almoravids and Almohads in Spain to the last Mahdi of Khartoum who so successfully thwarted the English. It happened in the same way or similarly with the risings in Persia and other Mohammedan countries. All these movements are clothed in religion but they have their source in economic causes; and yet, even when they are victorious, they allow the old economic conditions to persist untouched. So the old situation remains unchanged and the collision recurs periodically.7

Engels had apparently read the fourteenth-century Moroccan polymath Ibn Khaldun and was therefore familiar with his famous thesis about the three-generation lifespan of Muslim dynasties. What makes the passage relevant is that both systems, modern America and medieval Islam, unfold under a static body of law, the Constitution on one hand, and shariah on the other. Since the law is assumed to be perfect and unchanging, all problems must be the result of laxity in its observance. The solution, therefore, is to restore the law in all its ancient purity.

This was the message of medieval Muslim reformers like the Almoravids and Almohads, as Engels points out, and, curiously enough, it is the message of American reformers today.

At the height of Watergate, for instance, the black Texas Democrat Barbara Jordan declared in ringing tones: “My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total, and I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” The solution to Nixon’s misdeeds was to put the Constitution back on the pedestal where it belonged. A liberal New York Democrat named Elizabeth Holtzman excoriated Nixon for never stopping to ask himself, “What does the Constitution say? What are the limits of my power? What does the oath of office require of me? What is the right thing to do?” If he had read the Constitution, he would know the answer. Nearly half a century later, Nancy Pelosi denounced Donald Trump in the same ringing tones for “undermining a system, the beautiful, exquisite, brilliant, genius of the Constitution, the separation of powers, by granting to himself the powers of a monarch, which is exactly what Benjamin Franklin said we didn’t have.”8

The problem is always the same, and so the answer must be the same as well. When presidents go rogue, the faithful must draw them back to what ancient prophets like Benjamin Franklin said were their proper constitutional limits. If the Constitution says it it must be right because, after all, the Constitution is the Constitution. But, then, the Qur’an is also the Qur’an, so does that make it right as well? Here is what Ibn Khaldun said about Islam’s founding document:

The Qur’an … is in itself the claimed revelation. It is itself the wondrous miracle. It is its own proof. It requires no outside proof, as do the other wonders wrought in connection with revelations. It is the clearest proof that can be, because it unites in itself both the proof and what is to be proved. … All this indicates that the Qur’ân is alone among the divine books, in that our Prophet received it directly in the words and phrases in which it appears. … Inimitability is restricted to the Qur’an.9

So is the Constitution, that wondrous miracle that is its own proof, inimitable as well? According to liberal politicians such as Jordan, Pelosi et al., the answer is yes.

Towards a theory of the Constitution

The upshot is a political system as arid and unchanging as the constitutional structure that controls it. Which is what Madison wanted to accomplish, i.e. to sterilize politics so that the plantation system could continue ad infinitum.

The result is a society that is unable to grow and hence address a growing list of problems in a constructive and meaningful way. This is not to say there haven’t been bursts of reform. There have, obviously, but it’s invariably a case of one step forward and two steps back. Reconstruction led to Jim Crow and the unbridled corporate dictatorship of the 1880s and 90s. The mixed bag of reforms that comprised the Progressive Era led to the violent suppression of the Wobblies, grim wartime repression under Woodrow Wilson, the Palmer Raids, and Prohibition. The black revolution of the 1950s and 60s gave way to a growing “southernization” marked by the growth of pro-gun and anti-abortion movements and a sophisticated effort aimed at rolling back civil rights. This was observed the British journalist Godfrey Hodgson in 2004: “One of the surprise developments of the last thirty years has been that, where it was once assumed that the South would become more like the rest of the country, in politics and in many aspects of culture, the rest of the country has come to resemble the South.”10

Obviously, popular prejudice is a factor. But it’s an effect rather than a cause, given a slave constitution subject to no more but the most cursory reforms. Take the three-fifths clause that gave southern slaveholders twenty-five extra congressional seats and electoral votes. One might imagine that the abolition of slavery would have done away with such abuses. But with the termination of Reconstruction in 1877, the opposite was the case as black individuals now counted as “five-fifths” of a person for purposes of congressional apportionment— even though they couldn’t vote. Racism wound up expanding all the more, not despite the Constitution, but because of it. The seniority system rewarded racism by allowing the one-party South to expand its tentacles throughout Congress while the Electoral College and the Senate multiplied the power of agrarian states that were less populous and less developed, thus undermining democracy as well.

Despite the civil-rights reforms of the 1950s and 60s, the situation today is largely unchanged. In fact, in many ways, it is worse. Equal state representation, for instance, allows the majority of the population living in just ten states to be outvoted four-to-one in the Senate by the minority living in the other forty. Sixty years ago, the implications were neutral, at least in terms of race, since the top ten actually had fewer minorities than the nation as a whole. Today the situation is reversed with the top ten most populous states home to twenty percent more minorities. The result is a growing premium for whites in places like Montana, the Dakotas, New Hampshire, and Vermont and a growing disadvantage for minorities in places like California, Texas, and New York.

This is why America is racist – not because of some disease that Americans can’t kick, but because of a slave-era constitution that is beyond their control. Meanwhile, the filibuster allows senators from 21 states, like Montana, the Dakotas, etc., to veto any and all bills while the Electoral College gives voters in lily-white Wyoming more than twice as much clout in presidential elections as voters in a “minority-majority” giant like California.11

Not only does the Constitution prevent the people from tackling the problem of racial inequality, but it also prevents them from advancing on other fronts as well – environmental protection, labor, women’s rights, and so forth. Corporations adore the Constitution because by sterilizing democracy, it gives them a free hand to plunder society as they wish. The working masses are paying a growing price for a constitution that prevents them from taking society in hand and making it work for the benefit of the overwhelming majority.

Towards a theory of constitution breakdown

If the Constitution’s structure has remained static over the centuries why is it breaking down now? Why has Congress been gridlocked since the 1990s, why has the Electoral College overridden the popular vote in two out of the last five presidential elections, why do Supreme Court nominations generate such bitter fights on Capitol Hill, and why is everyone filled with trepidation over what November will bring – whether the vote count will be honest, whether Trump will leave the White House peacefully if he’s defeated, whether there will be fighting in the streets, etc.? There’s more than a whiff of Weimar in the air. But why now as opposed to, say, the 1950s?

The answer has to do with the larger arc of capitalist development. Les trentes glorieuses, the golden age of postwar capitalism, was a time when seemingly everything worked. In Washington, three white men, two Texans and a Kansan– Dwight Eisenhower, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson – essentially ran the government. Although some leftists feared that Joe McCarthy represented a fascist resurgence, what’s striking now is how neatly Eisenhower was able to nip the threat in the bud. Ike handpicked lawyer Joe Welch to confront the senator at the Army-McCarthy hearings, and the patrician Welch was careful to rehearse his famous line – “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?” – beforehand.12 In the end, McCarthy was denied his beer-hall putsch and collapsed just a few months after the Senate voted overwhelmingly to condemn his behavior.

So the center held – and what’s more, it continued to hold even during the tumult of the 1960s. Indeed, Watergate marked a high-point of constitutional reverence in 1974. In that moment Alexander Cockburn couldn’t resist poking fun at American piety, as a columnist at the old Village Voice:

On the word front, the sky is still dark with clichés coming home to roost. The nightmare of Watergate is slowly receding, the long national trauma is over, the country’s profound need for rest has been appeased, a catharsis has taken place, a curtain is falling on a tragedy almost Greek in its dimensions, agony is giving way to peace, the nation’s wounds are being healed, the healing has begun, the Constitution has worked, the system has worked, pretty well everything you’ve ever heard of has worked, except the economy.13

The economy had ceased working thanks to the 1973 Arab oil embargo and the unraveling of the great postwar boom, this meant that the Constitution would soon stop working as well. Although Republicans went along with Watergate, temperatures quickly started to rise. The 1980s saw the Iran-contra scandal in which a lieutenant colonel named Oliver North denounced Congress like a two-bit Latin American putschist, with legislators too intimidated to say anything in return. House Speaker Newt Gingrich declared war on the Clinton administration with his 1994 “Contract with America” and then tried to use the Monica Lewinsky affair to drive him out of office in 1998. November 2000 saw the “Brooks Brothers Riot” in which Republican thugs tried to disrupt the vote count in Miami in order to steal the election for George W. Bush.14 Republicans tried to use “Birthergate” and “Benghazi-gate” to sabotage another Democratic administration after Obama won office in 2008. Then, as if to prove that subversion was not a one-way street, Democrats tried to overthrow Trump via a no-less-bogus pseudo-scandal known as Russiagate.

Russiagate deserves a book in itself. Although liberals will no doubt cry out in protest, it plainly amounted to an attempted coup d’état by Democrats, the corporate media, and the intelligence agencies, all of whom were up in arms over Trump’s confused ramblings about a rapprochement with Russia and who therefore pushed the theory that he was a Kremlin agent. It was a paranoid fantasy cooked up by unrepentant cold warriors like Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, Adam Schiff, and Robert Mueller. But beneath it lay a crisis of imperialism that had been building for years, a crisis of capitalism, and a deepening constitutional breakdown. It was the interaction of all three that made the situation so explosive.

As the Marxist economist Michael Roberts has noted, capitalism has been in the grips of a crisis caused by declining profitability since the late 1960s. The 1970s, the decade of de-industrialization and rocketing energy prices, saw a long sickening plunge in corporate profits, while the neoliberal “reforms” of the 1980s saw a brief uptick. With the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the dot-com bust in 2001, capitalism resumed its downward course. It plunged again in 2007-08 and, thanks to Covid-19, has now gone crashing through the floor.15

Each downward plunge caused the mood in Washington to turn nastier and nastier while convincing disgruntled whites in the hinterlands that the cost of empire is not worth the blood that they had to shed. Deteriorating social conditions among rural whites sparked the anger that provided Trump with his margin of victory in 2016. American society was coming apart at the seams because the constitutional structure was disintegrating with astonishing speed.

The Declaration of Independence, America’s original founding document, says with regard to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that “whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.” After nearly a century and a half, Americans have arrived right back where they started, i.e. with a government that is undermining their safety and happiness at every turn and which they therefore must replace, not in part but in toto. They can’t do so with eighteenth-century methods— only those of the twenty-first, which is to say with revolutionary socialism.

But that’s a subject for another essay.