Interpreting Stalin’s fledgling revolutionary career through his later status as a brutal labor dictator obscures an early whole-hearted admiration for the works of Kautsky and Lenin. By Lawrence Parker.

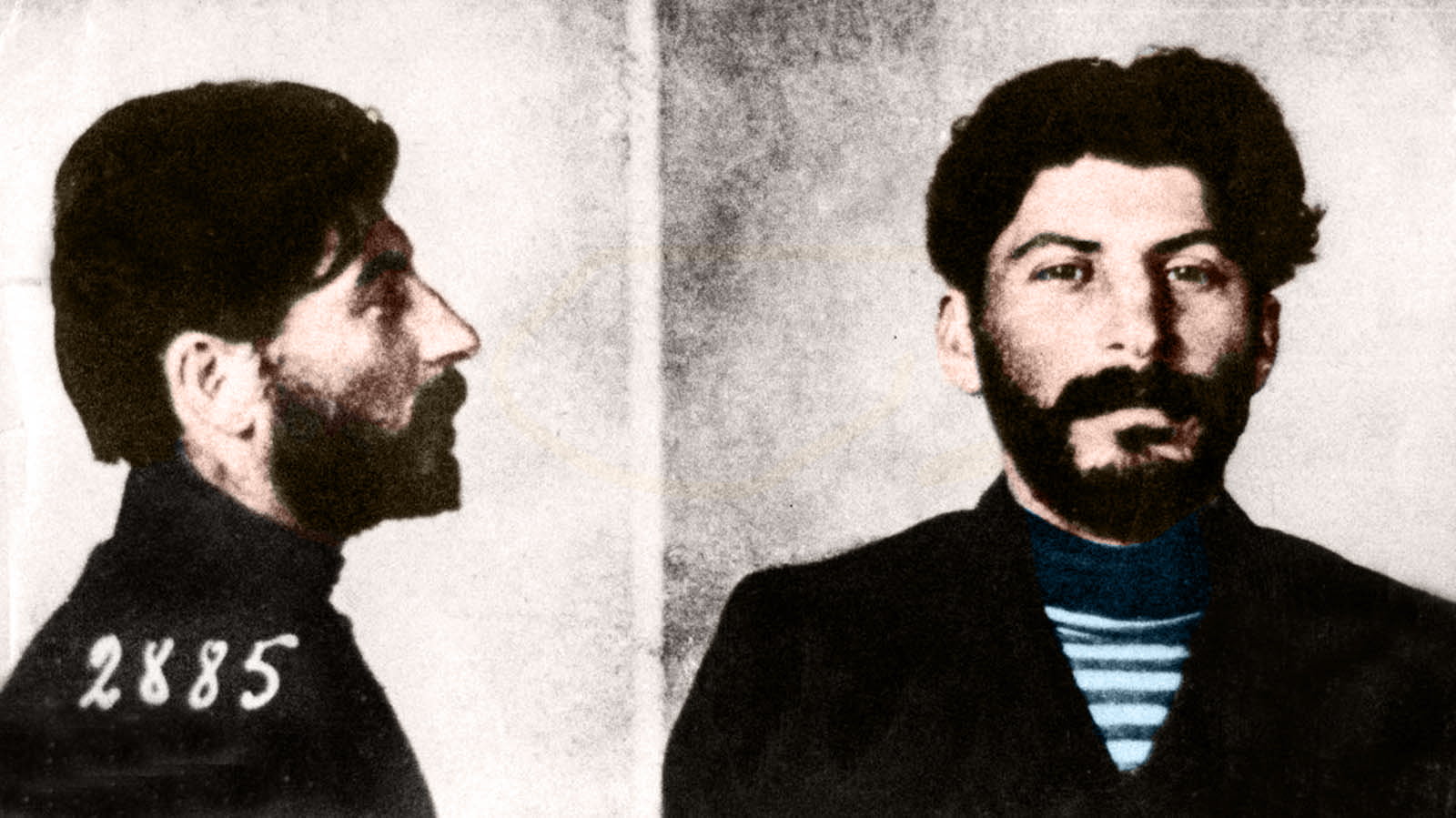

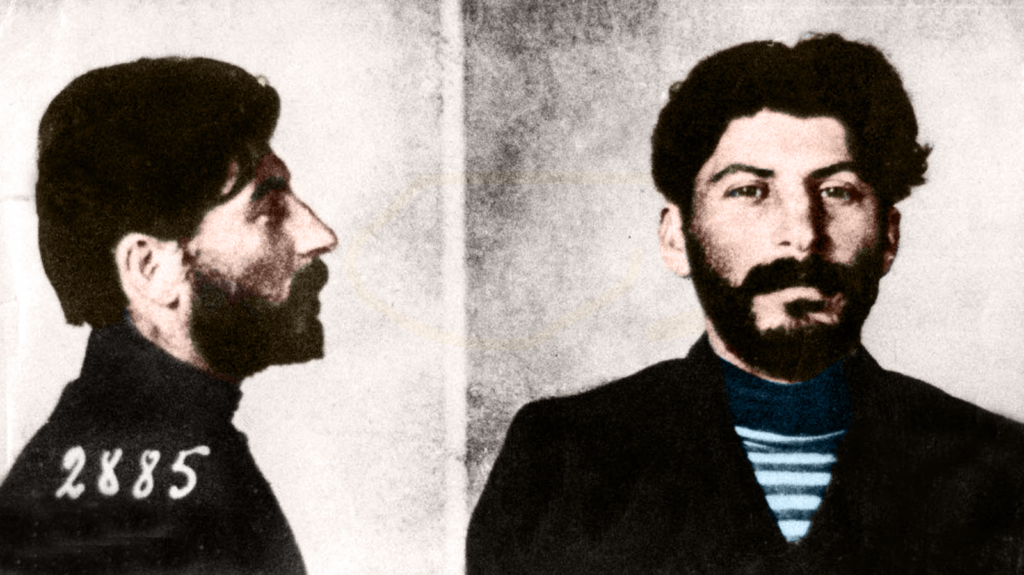

Writing in 1946, Max Shachtman made an astute point about Joseph Stalin. In reviewing Leon Trotsky’s biography of Stalin, he said that “we do not recognize the young Stalin in the Stalin of today; there does not even seem to be a strong resemblance”.1 By 1946, Stalin was the ‘generalissimus’ of the Soviet Union, heading up a brutal dictatorship over and against the working class. Little wonder it was so difficult for the left to then understand the mentality of the young Georgian revolutionary who joined the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) at the turn of the 20th century, particularly after Stalin’s back story had been ‘enlivened’ by a few decades of lying propaganda.

Shachtman’s own line of reasoning appears to be traceable to contradictions inherent in Trotsky’s (unfinished) biography of Stalin. We partly have the imposition of a schema, a kind of ‘original sin’ that suggests Stalin was always fundamentally bad:

Never a tribune, never the strategist or leader of a rebellion, [Stalin] has ever been only a bureaucrat of revolution. That was why, in order to find full play for his peculiar talents, he was condemned to bide his time in a semi-comatose condition until the revolution’s raging torrents had subsided.2

However, Trotsky offered other statements that make such overarching judgments problematic from the standpoint of method. He had this to say about Stalin at the beginnings of the anti-Trotsky triumvirate (which included Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev) in circa 1923:

Who could have thought during those hours that from the midst of the Bolshevik Party itself would emerge a totalitarian dictator who would repeat the calumny of Yarmelenko with reference to the entire staff of Bolshevism? If at that time anyone would have shown Stalin his own future role he would have turned away from himself in disgust.3

Now, calling someone “only a bureaucrat of revolution” is obviously a different designation to that of “totalitarian dictator”, but Trotsky does establish the important principle that historical circumstances changed Stalin profoundly, which could be taken to imply that history could have produced a number of different versions of Stalin, so to speak.

With this in mind, it might be better to view pre-1917 Stalin as a Social Democratic praktik, one of its intelligent workers involved in the running of its local and national organizations and intent on furnishing the proletariat with a deep-seated Marxist knowledge of its heroic mission to overthrow Tsarism (i.e. the active, hegemonic notion of a Marxist propagandist). As part of this role, Stalin, as a follower of Lenin, also sought to emulate the revolutionary achievements of German Social Democracy and its leaders and communicated his admiration. Subsequent Soviet notions from Stalin and others of Russian Bolshevism as sui generis, set apart from the international revolutionary movement, are invented narratives, absent from Stalin’s early work. This, I would argue, is one of the messages to be gleaned from Stalin’s pre-1917 writings.

When looking back at his own works from 1901-07, Stalin classed himself as one of the “Bolshevik practical workers”, characterized by “inadequate theoretical training” and a “neglect, characteristic of practical workers, of theoretical questions”.4 As Tucker has pointed out, this characterization allies itself with the mature image of Stalin as a “pragmatist”, intent on the practical effort in constructing ‘socialism’ inside the borders of the Soviet Union rather than on supposed airy-fairy ideals of ‘world revolution’.5 In fact, a prosaic reading of ‘practical’ (as opposed to praktik) obscures what Stalin was in these years. Tucker asserts that Stalin’s “original function as a Social Democratic ‘practical worker’ was propaganda” and that “knowledge of the fundamentals of Marxism and the ability to explain them to ordinary workers were [Stalin’s] chief stock-in trade as a professional revolutionary”.6 Little wonder, then, that this propagandist graduated to writing unspectacular but worthy articles for Georgian Social-Democratic newspapers such as Brdzola (The Struggle).

Stalin’s downplaying of his theoretical and literary credentials was not followed through consistently in Soviet literature. Although Stalin reduced his personal role in his edits to the 1938 Short Course on the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks)7, other works, for example by Soviet historian Yemelyan Yaroslavsky, offer a more realistic appreciation of Stalin popularizing the ideas of Marx, Engels, and Lenin in early theoretical writings and having the “closest affinity” with Lenin.8 Other assertions of Yaroslavsky, that in 1905 “Stalin worked hand in hand with Lenin in hammering out the Bolshevik line”9 are fraudulent. Stalin was simply a follower of Lenin in this period.

Stalin also offered a 1946 health warning on his early works (including ones up until 1917), stating that they were “the works of a young Marxist not yet molded into a finished Marxist-Leninist” and that they “bear traces of some of the propositions of the old Marxists which afterward became obsolete and were subsequently discarded by our party”.10 Stalin gave two examples: the agrarian question and the conditions for the victory of the socialist revolution. But such a warning was also pertinent to articles praising German Social-Democratic figures such as Karl Kautsky and August Bebel. The Stalin of 1946 would not have wanted communist readers thinking these were suitable figures to emulate, given the line that had emerged in his manifold corrections to the 1938 Short course, where it was argued that after Engels’ death in 1895, West European Social-Democratic parties had begun to degenerate from parties of social revolution into reformist parties.11 However, at least in the terms in which he referenced German Social-Democracy, Stalin’s praise was not a facet of his own immaturity or ‘immature’ Bolshevism, given that as late as 1920 Lenin was looking back favorably on the influence of Kautsky in the early years of the 20th century: “There were no Bolsheviks then, but all future Bolsheviks, collaborating with him, valued him highly.”12

‘An Outstanding Theoretician of Social-Democracy’

A flavor of Stalin’s own praise can be gleaned from an article from 1906, in which he discussed German opportunists accusing Kautsky and Bebel of being Blanquists. Stalin said: “What is there surprising in the fact that the Russian opportunists… copy the European opportunists and call us Blanquists? It shows only that the Bolsheviks, like Kautsky and [French socialist Jules] Guesde, are revolutionary Marxists.”13

In February 1907, Stalin wrote a preface to Kautsky’s The Driving Force and Prospects of the Russian Revolution, which began unambiguously:

Karl Kautsky’s name is not new to us. He has long been known as an outstanding theoretician of Social-Democracy. But Kautsky is known not only from that aspect; he is notable also as a thorough and thoughtful investigator of tactical problems. In this respect he has won great authority not only among the European comrades, but also among us.14

In the face of such unambiguous praise, the Soviet editors of Stalin’s Works were forced to partly retract the general suggestion of the 1938 Short Course that Western Social Democracy had begun to disintegrate into reformism after the death of Engels in 1895. They argued that the likes of Kautsky had retained their revolutionary integrity a decade beyond this and that the revolutionary Russian party was, implicitly, not sui generis:

K Kautsky and J Guesde at that time [1906] had not yet gone over to the camp of the opportunists. The Russian revolution of 1905-07, which greatly influenced the international revolutionary movement and the working class of Germany in particular, caused K Kautsky to take the stand of revolutionary Social Democracy on several questions.15

But Stalin was still praising the revolutionary wing of German Social Democracy beyond 1907. In 1909 he was stating that “our movement now needs Russian Bebels, experienced and mature leaders from the ranks of the workers, more than ever before”.16 This after August Bebel, the leading German Social-Democratic parliamentarian (1840-1913). Stalin returned to the example of Bebel on the latter’s 70th birthday in 1910, discussing “why the German and international socialists revere Bebel so much”.17 He concludes:

Let us, then, comrades, send greetings to our beloved teacher — the turner August Bebel! Let him serve as an example to us Russian workers, who are particularly in need of Bebels in the labor movement. Long live Bebel! Long live international Social Democracy!18

Writing much later in 1920, Stalin was prepared to concede that figures such as Kautsky and the Russian Georgi Plekhanov had been worthy theoretical leaders of the movement. Stalin argued that these were examples of “peacetime leaders, who are strong in theory, but weak in matters of organization and practical work”, although their influence was limited to only “an upper layer of the proletariat, and then only up to a certain time”.19 Stalin added: “When the epoch of revolution sets in, when practical revolutionary slogans are demanded of the leaders, the theoreticians quit the stage and give way to new men. Such, for example, were Plekhanov in Russia and Kautsky in Germany.”20 Stalin thus pictured Lenin as the successor both to theoretical leaders such as Kautsky and to “practical leaders, self-sacrificing and courageous, but… weak in theory” such as Ferdinand Lassalle and Louis Auguste Blanqui.21 This line of 1920 did represent a shift from Stalin’s argument in 1907, quoted above, that Kautsky had not been just a theoretical leader but also “a thorough and thoughtful investigator of tactical problems”. Nevertheless, in line with Lenin, Stalin was not yet prepared to give up his longstanding admiration for Kautsky.

Stalin Advocates the ‘Merger Theory’

Stalin gave an even more robust defense of Kautsky in May 1905 when he “recycled” the latter’s arguments in order to defend Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? against Menshevik interlocutors in Georgia.22 Stalin quoted a passage from Kautsky writing in the theoretical journal Die Neue Zeit (in 1901-02) that Lenin had used and that subsequently became infamous for apparently illustrating Lenin’s disdain for proletarian leadership abilities: “… the vehicle of science is not the proletariat, but the bourgeois intelligentsia (K Kautsky’s italics). It was in the minds of individual members of that stratum that modern socialism originated, and it was they who communicated it to the more intellectually developed proletarians…”23 The often tedious arguments that center on this passage essentially mix up an empirical debate about the origins of proletarian class consciousness with a dialectical one about its future development. Stalin correctly understood this point as working out the difference between initial “elaboration” and the future “assimilation” of socialist theory.24 Neither Kautsky nor Lenin was guilty of disdain for the proletariat because such a dynamic was always presaged on the merger of socialism and the worker movement. In other words, the future of socialism was not beholden to its debatable origins.25

But what of Stalin? Surely, we might expect that someone who had, in Trotsky’s words, only ever been a “bureaucrat of revolution” to have not been in favor of any such democratic merger with the proletariat. In fact, Stalin made his positive appreciation of the merger on the very first page of his defense of Lenin, presaging his article with an (unattributed) Kautsky quote: “Social-Democracy is a combination of the working-class movement with socialism.”26 This is no isolated motif from the article and Stalin elaborated on this point at some length:

What is scientific socialism without the working-class movement? A compass which, if left unused, will only grow rusty and then will have to be thrown overboard. What is the working-class movement without socialism? A ship without a compass [that] will reach the other shore in any case but would reach it much sooner and with less danger if it had a compass. Combine the two and you will get a splendid vessel, which will speed straight towards the other shore and reach its haven unharmed. Combine the working-class movement with socialism and you will get a Social-Democratic movement [that] will speed straight towards the ‘promised land’.27

Stalin was convinced that the Russian proletariat would have no problem in assimilating and adopting Social-Democratic revolutionary politics. Directly opposing the line of Georgian Menshevik critics on the issue of the intelligentsia originating socialist theory, he said:

“But that means belittling the workers and extolling the intelligentsia!” – howl our ‘critic’ and his Social-Democrat [Menshevik Tiflis newspaper] … They take the proletariat for a capricious young lady who must not be told the truth, who must always be paid compliments so that she will not run away! No, most highly esteemed gentlemen! We believe that the proletariat will display more staunchness than you think. We believe that it will not fear the truth!

There is not a trace in this of any predestination towards some anti-proletarian bureaucratic hell and Stalin merely comes across as an energetic, if entirely unoriginal, supporter of Kautsky and Lenin, adept at employing their arguments against local Mensheviks in Georgia.

Stalin remembered the ‘merger theory’ when he was editing the 1938 Short Course. Among his very substantial reworking of chapter two, which dealt with the period of What Is To Be Done?, Stalin wrote that Lenin’s work: “Brilliantly substantiated the fundamental Marxist thesis that a Marxist party is a union of the working-class movement with socialism.”28 He also repeated his line of 1905 in suggesting that belittling socialist consciousness meant “to insult the workers, who were drawn to consciousness as to light”. 29It is a bitter irony of historiography that this quack Stalinized history, on this particular issue at least, offers more light on the topic than the vast majority of academic or Trotskyist treatments of What Is To Be Done?.

Deutscher and ‘Foreshadowing’

Stalin’s early writings have been tied up with a problem of ‘foreshadowing’, where they become a roadmap to his future career as a labor dictator. A good example of this occurs in Isaac Deutscher’s famous biography, when he discussed Stalin’s first comment on the split between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, made in an article entitled ‘The Proletarian Party and the Proletarian Class’ from January 1905. This piece dwelt upon the dispute over party membership that had arisen at the RSDLP’s second congress in 1903. Stalin presented Lenin’s formula as: “… a member of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party is one who accepts the program of this party, renders the party financial support, and works in one of the party organizations”. The Menshevik Julius Martov’s was presented as: “A member of the RSDLP is one who accepts its program, supports the party financially and renders it regular personal assistance under the direction of one of its organizations.”3031

Deutscher argued correctly that the Stalin piece is mostly a re-rendering of Lenin’s arguments on the subject but suggested that Stalin added his own sinister confection with an emphasis on the “need for absolute uniformity of views inside the party”.32 This “smacked of that monolithic ‘orthodoxy’ into which Bolshevism was to change after its victory, largely under Koba’s own guidance”.33 Deutscher used the following passage from ‘The Proletarian Party and the Proletarian Class’ to illustrate the point:

Martov’s formula, as we know, refers only to the acceptance of the program; about tactics and organization it contains not a word; and yet, unity of organizational and tactical views is no less essential for party unity than unity of programmatic views. We may be told that nothing is said about this even in Comrade Lenin’s formula. True, but there is no need to say anything about it in Comrade Lenin’s formula. Is it not self-evident that one who works in a Party organization and, consequently, fights in unison with the party and submits to party discipline, cannot pursue tactics and organizational principles other than the party’s tactics and the party’s organizational principles?34

‘Unity’, such as that unity gained, for example, around a democratic vote at a congress between contending factions that have argued out their differences, should not be immediately transposed into ‘monolithic unity’, particularly if one bears in mind that this is the Stalin of 1905 and not 1935 talking. Deutscher half-conceded this point almost immediately by arguing “that ‘monolithism’ was still a matter of the future”.35

However, Stalin had no issue with Lenin’s formulation around acceptance, not agreement, in relation to the party program:

To the question – who can be called a member of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party? – this party can have only one answer: one who accepts the party program, supports the party financially and works in one of the party organizations. It is this obvious truth that comrade Lenin has expressed in his splendid formula.36

Acceptance implies diversity, in that one can clearly accept something without agreeing with everything about it.

Stalin’s real problem with Martov was over the issue of party organization and discipline. What clearly lay behind Stalin’s emphasis was the dispute at the RSDLP second congress over the appointment of the Iskra editorial board. Martov refused to serve on the three-man board that had been newly elected at the congress and joined the three former members of the board (Axelrod, Zasulich and Potresov) in declaring a boycott on their own participation in party institutions.37 After a succession of maneuvers, the old editorial board rejected by the congress reconstituted itself, a move that lacked political legitimacy. Stalin remarked bitterly on this in 1905 that “these obstinate editors did not submit to the will of the party, to party discipline”. He added: “It would appear that party discipline was invented only for simple party workers like us!”38 This then led to a Bolshevik emphasis on partiinost: acting like a modern political party with a sovereign congress and a disciplined membership. This was opposed to a kruzhok, or ‘little circle’, mentality that did not recognize the larger bonds of partiinost.39 The apparently unmovable Iskra editorial board was clearly an example of the latter.

It therefore becomes obvious that Stalin’s ‘The Proletarian Party and the Proletarian Class’ article shared this partiinost standpoint in terms of its emphasis on working in a disciplined manner in party organizations. Stalin had previously polemicized against the restrictions involved in limiting the movement to small circles as opposed to a party, arguing that it was “the direct duty of Russian Social Democracy to muster the separate advanced detachments of the proletariat, to unite them in one party, and thereby to put an end to disunity in the Party once and for all”.40 Stalin was thus extremely disappointed that this hadn’t been the outcome of the second congress: “We party workers placed great hopes in that congress. At last! – we exclaimed joyfully – we, too, shall be united in one party, we, too, shall be able to work according to a single plan!”41

The above offers important contextualization for the arguments offered in ‘The proletarian party and the proletarian class’. Stalin said:

What are we to do with the ideological and practical centralism that was handed down to us by the second party congress and which is radically contradicted by Martov’s formula [on party membership]? Throw it overboard?42

This should not be read as some kind of paean to future dictatorship but rather a reflection of a partiinost attitude in terms of what he sees as vital to the future success of the RSDLP and annoyance with the likes of Martov that this had not been achieved. Similar conclusions should be gleaned from Stalin’s statement that: “It looks as though Martov is sorry for certain professors and high-school students who are loath to subordinate their wishes to the wishes of the party.”43 This is not a universal plea for unpleasantness towards professors and students but a reflection of a practical situation in which Martov and the other Iskra editors had refused to subordinate themselves to what Stalin saw as a sovereign RSDLP congress and to submit to the same sort of party discipline that he himself was prepared to. Stalin clearly thought that had serious implications for Martov’s definition of party membership.

Deutscher’s argument that ‘The Proletarian Party and the Proletarian Class’ was the herald of future totalitarianism is a particularly lurid fantasy on his part. If anyone other than Stalin had written such an article in 1905, it is almost certain that it would be an entirely plausible and non-controversial statement of Bolshevik views in response to the situation after the RSDLP’s second congress.

Form and Content in Stalin

Given that questions of style and form cannot be mechanically separated from political ones, and considering that Stalin’s prose in the articles that have been discussed above can at best be classed as somewhat plodding, often repetitive and generally unremarkable in the canon of Marxism, does this not prove something? Does it not show that a bureaucratic soul lurked deep within what were ostensibly run-of-the-mill Bolshevik writings? I think not, but to explore this question we need to go back to Trotsky.

Trotsky was not flattering about Stalin’s early journalism, arguing it sought to “attain a systematic exposition of the theme” but such an “effort usually expressed itself in schematic arrangement of material, the enumeration of arguments, artificial rhetorical questions, and in unwieldy repetitions heavily on the didactic side”.44 Trotsky made the harsh judgement: “Not a single one of the articles [Stalin] then wrote would have been accepted by an editorial board in the slightest degree thoughtful or exacting.”45 Of course, this was not true of 1913’s Marxism and the national question (another work heavily influenced by Kautsky46), which was highly esteemed by Lenin. However, Trotsky attributed any positives almost solely to Lenin’s inspiration and editing.47 However, Trotsky did qualify his thoughts on Stalin’s early writings, stating that underground publications were not notable for their “literary excellence, since they were, for the most part, written by people who took to the pen of necessity and not because it was their calling”.48 This sense of necessity spills over into the way Trotsky sees that these works were received by their audience:

It would, of course, be erroneous to assume that such articles did not lead to action. There was great need for them. They answered a pressing demand. They drew their strength from that need, for they expressed the ideas and slogans of the revolution. To the mass reader, who could not find anything of the kind in the bourgeois press, they were new and fresh. But their passing influence was limited to the circle for which they were written.49

So, Trotsky seemed to conclude that Stalin’s work was mediocre, unexceptional but necessary. Similarly, if Stalin suffered an “absence of his own thought, of original form, of vivid imagery – these mark every line of his with the brand of banality”50 then one would wonder whether this is just a paler reflection of what Lih has called Lenin’s “aggressive unoriginality”.51

Trotsky also alluded to Lenin’s unoriginality in his comments on the development of ‘Leninism’. In its Soviet bureaucratic form, ‘Leninism’ was a unique development of Marxism, or Russian Marxism sui generis; in Trotsky’s words, “trying to work up to the idea that Leninism is ‘more revolutionary’ than Marxism”.52 This is coded in notorious formulas such as this one from Stalin’s ‘The Foundations of Leninism’ (1924):

Leninism is Marxism of the era of imperialism and the proletarian revolution. To be more exact, Leninism is the theory and tactics of the proletarian revolution in general, the theory and tactics of the dictatorship of the proletariat in particular.53

Trotsky steadfastly denied that Lenin developed anything new, stating that his former leader “was a million miles away from any thought of inventing a new dialectic for the epoch of imperialism” (which is interesting, because this tenet of ‘Leninism’ is repeated by many of Trotsky’s current epigones).54 To underline the point, Trotsky argued that Lenin “paid his debts to Marx with the same thoroughness that characterized the power of his own thought”55, “failed to notice his break with ‘pre-imperialistic Marxism’”56; and that “Lenin’s work contains no new system nor is there a new method. It contains fully and completely the system and the method of Marxism”.57 But once this idea of the absolute uniqueness of ‘Leninism’ is knocked off its pedestal and we begin to understand the power of Lenin lay in his unoriginality, we do then begin to lessen the difference between other unoriginal writings such as the early works of Stalin. This is not to equate Lenin and Stalin – the latter was simply a follower of his leader – but it is not a sin in the annals of Bolshevism to be repetitive and unoriginal, even though figures such as Lenin had more obvious theoretical power.

Conclusion

This is not an exercise in rehabilitating the early career of Stalin in order to shine a light forward onto the so-called progressive aspects of the Soviet Union. After around 1928, Stalin’s bureaucratized regime was not a ‘workers’ state’ in any sense. Projecting positivity forwards would only repeat the methodological errors of ‘foreshadowing’, as Stalinists do, rather than projecting negativity backwards, as many Trotskyists do. What this article is attempting to establish is that the contours of Stalin’s early ideological development were shaped by the contours of being a Bolshevik praktik, with a consequent heavy reliance on the revolutionary ideas of the Second International’s leading thinkers. The later, ‘other’ Stalin was the product of an isolated and poverty-stricken revolution that had run out of steam by the early 1920s. There was no ideological ‘original sin’ or ‘smoking gun’ before that time.