Introduction and translation by Medway Baker.

Since the fall of the USSR and the definitive failure of the Russian Revolution, many among the left have begun to question the validity of Marxism, and Lenin’s elaboration of it. Some turn to anarchism; many others turn to “democratic socialism” or left-wing populism. There are also those who classify themselves as Marxists, but reject the legacy of October 1917 and the politics of the Bolsheviks: I include in this category both left-communists of the German/Dutch and right-opportunists (some of whom claim the legacy of Kautsky or other great Marxist thinkers).

In short, there are many on the left who have been asking the question: “Is Marxism (or Bolshevism) obsolete?” This is not a foolish question; the USSR, and along with it so many of the assumptions underlying communist politics, is a thing of the past. The official communists are deprived of their guiding light, the Trotskyists’ hope for political revolution in the USSR was crushed, and the organized left has retreated as neoliberal capitalism advances across the world. It is correct and, indeed, necessary to question past dogmas.

But Marxism goes beyond the USSR, and Bolshevism goes beyond its contemporary manifestations. It is easy to forget that Marx and Engels argued as a minority within the socialist organizations of their day for scientific socialism; that the Marxists of the Second International often argued as minorities within their parties for Marxist politics; that the nucleus of the Comintern, the antiwar left faction of the Second International, argued as a minority for revolution in the face of social democracy’s capitulation to imperialism.

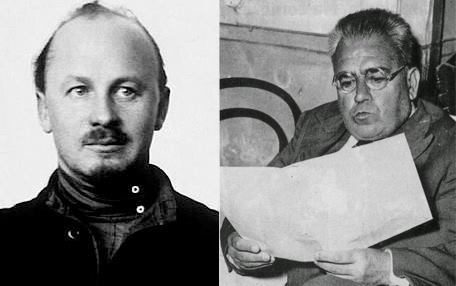

Charles Rappoport was a French Marxist who argued as a minority for Marxist politics in the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO), a member party of the Second International. The SFIO was dominated by two main tendencies. On the one hand were the Guesdists, followers of Jules Guesde, who claimed the legacy of Marxism while rejecting Marxist political strategy; it was in reference to this tendency that Marx famously pronounced, “[if this is Marxism, then] I am not a Marxist.” On the other hand were the reformists, of whom Jean Jaurès was a prominent leader. Despite the revolutionary sloganeering of the Guesdists, neither tendency was prepared to build a mass, revolutionary workers’ party capable of taking power during a crisis of state; this was proven at the beginning of the First World War, when Jaurès (a prominent pacifist) was assassinated, and Guesde chose to support the war.

Rappoport was a member of neither tendency, although he frequently found himself in alliance with the Guesdists—who rejected taking ministerial positions in the bourgeois state, etc.—in the struggle against reformism. He was fanatically committed to the notion of scientific socialism: of Marxism as a scientific research project, and of communism as “the triumph of science, of art, and of the creative genius of man,” which he opposed to its role as “slave of the wealthy” under capitalism. He declared, “That science become the people’s, and that the people become learned (not simply schooled), this is our ideal.” He was equally committed to Marxism as a revolutionary political project.

He broke with the Guesdists in the leadup to the First World War, accusing them of cretinism and charging them with responsibility for the failure of Marxism to take root in France; after the beginning of the war, he began ending his articles with “The Second International is dead. Long live the Third International!” Although he was suspicious of Lenin and did not identify himself as a Bolshevik—indeed, he at first denounced the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and predicted the failure of the Russian Revolution, accusing Lenin of Blanquism—he wholeheartedly supported the formation of the French Communist Party (PCF) in 1920.

As Rappoport learned more about the situation in Russia, and as he worked within the Comintern, he came to largely accept Lenin’s politics, while remaining critical of the Comintern and later Stalin. He was always kept from the reins of power within the party, and especially after “Bolshevisation”, he was less and less able to engage critically with others in the movement. In effect, he was reduced to a pamphleteer, aside from his own projects.

It was during the Popular Front and the Great Purge that he finally became totally disillusioned with the official communist movement. In 1938, he resigned from the party. He characterized the PCF as the “registry office for Stalin’s orders, or those of his speaker, Comrade [Georgi] Dimitrov.” Even as he denounced Stalin and hoped for the eradication of the Stalinist regime, though, Rappoport defended the legacy of October, and understood that the USSR could serve to terrify the capitalists and inspire the nations of the colonial world—and this could only be positive in his view.

Before the dissident Marxists of France had a chance to begin charting a new course, the Second World War began. Charles Rappoport died in 1941, with France under Nazi occupation, the USSR under siege, and himself thoroughly disillusioned with the socialist movement—yet always a staunch defender of revolutionary Marxism, of scientific socialism.

Is Marxism Obsolete?

This is translated from a transcription of a speech Charles Rappoport gave at a conference on 1 February, 1933, titled “Le marxisme est-il périmé ?” by Medway Baker.

Marxist Theory

Comrades,

Marxist theory has been known for a long time. In 1918, we celebrated the centenary of Karl Marx’s birth in 1818. I’m telling you this because I wrote the article on Marx’s centenary while in La Santé Prison, where I had as jailmate Mr. Caillaux, the originator of the word of the day: “Marxism is obsolete.” And, as I was in prison and could not author articles under my own name during the war, I signed it “a free man!”

This year, we commemorate the fifty-year anniversary of Karl Marx’s death, on 14 March 1883.

Marxism is not an abstract theory. It is the algebra of revolution. It is the science of the proletariat, the truly revolutionary class, as Marx said and as we see every day in our own lives.

It is not surprising that those who have something to conserve, who are by definition conservatives, who want to maintain the existing society, combat Marxist theory, since Karl Marx said to capitalist society, “Brother, you must die!” And as the present society would sooner vanquish all humanity than consent to disappear itself, not a single year passes without writers, journalists, academics, and others trying to refute Marx. It has even become a specialty in Germany, where there is a whole category of people known by the German name Marxvernichter, which means “assassins of Marx,” and where every year we see the same assassination rehashed. This is why there is an entire literature on Marxism which, by its volume (although not by its value), will soon surpass all that we have written on Shakespeare, Goethe, or Kant, the three men about whom the most has been written.

The attacks against Marx are not surprising. Marx has never been more topical, Marxist ideas have never been so alive as today. I will give this presentation on Marxism without passion; objectively, because that is what Marx deserves, having been an objective thinker.

There are two aspects to Marx: there is his method, and there are his theories.

Let us see first whether the method is “obsolete.”

The Marxian Method

Marx’s method is before all else a materialist method. Marx was the enemy of verbalism, even that verbalism playing at revolutionism. He was against all those who, like the ingenious Alexander Herzen said of his friend Bakunin, incorrectly “took the second month of pregnancy to be the ninth.” The result? Miscarriage! He was against the émigrés who, after the failure of the 1848 revolution, wanted to restart it as soon as possible. So that the revolution might triumph, we need to wait for the material conditions that will assure victory. He was the opponent of those who, under the pretext of taking a faster route, jumped from the sixth floor to the ground instead of taking the stairs. Evidently, this is a faster route. You’ll arrive sooner, but in what state!

Marx applied the materialist method. He studied reality before all, the material conditions of social life. He was, at the same time, a dialectician. This means that he understood that it is necessary to find in each society the self-destructive elements of that society, which develop inside it, as well as the constructive elements of the new society. One could say that each society carries in its womb the new society, as the mother carries the child.

And if Marx and his partisans give socialism the qualifier of “scientific,” it is because they found within capitalist society, the existing economic society, the self-destructive elements of that society as well as the constructive elements of the new society.

The Marxist method is based on the concept of evolution towards revolution. Now, the concept of evolution is at the base of all sciences and all modern concepts, with the difference that evolutionists in the vein of Spencer halt the law of evolution at the threshold of the current society: everything evolves except capitalism. The law of evolution must respectfully sidestep the Bank of France and the other banks—it loses its authority, it ceases to be applicable; everything evolves except capitalist property and the capitalist mode of production. Marx, on the contrary, with an implacable logic, said, “No! If everything changes, if everything transforms, there is no reason that capitalism and its mode of production should remain at their present stage; there is no reason that historical evolution should stop at the capitalist stage.”

Must we return to the dogmas of the invariability of species, of the stagnation of all that exists, to old geology, to old astronomy? Modern astronomy and geology demonstrate that the comets and the planets are formed gradually and that the earth has passed through diverse stages.

Marx is in agreement with the modern theory of evolution, which does not exclude the rapid passage from evolution to revolution: today’s theory of evolution admits, along with de Vries, the existence of abrupt passages—jumps—in the regular march of things.

Marx never pits evolution against revolution. Thus, the child, who develops in the mother’s womb, enters the world in a bloody storm. Jaurès tried in vain to persuade the bourgeoisie that we could go to Morocco by way of “peaceful penetration.” Despite his good intentions, his power of persuasion and his honesty, he couldn’t make this idea of “peaceful penetration” victorious. You know that we are still at war in Morocco.

So, according to the Marxian method, according to Marx’s dialectic, we should not pit evolution against revolution.

Are these ideas obsolete? Should we return to idealist verbalism? Francis Bacon, one of the founders of modern philosophy, said that there are two sources of truth: there is the method of the bees, tributaries of the surrounding materials, of the plants and the flowers from which they draw their honey; and there is the method of the spiders, who draw everything from their own substance. The idealists “have a spider in their head”, which is to say that they draw everything from their head, which leads them to take words for realities.

In the present era, it is common to abuse strong words. During the war, all the idealist baggage was brought into the light. We were told every day that those who parted for the front were going to fight for “justice”, for “rights”, for “civilization”. This abuse of idealist phrases, empty of sense in our present society, continues today. This abuse has so little diminished that, yesterday even, there was a gathering of the small and middle proprietors at the Salle Wagram, organized by the reactionaries. In the name of which principles did they organize against the demands of the socialists and the democrats? It is in the name of equality before tax, it is in the name of the rights of man that the rich demand to pay as much as the poor, Rothschild as much as Rappoport!

In effect, in the name of the rights of man and the citizen, the poor must pay as much as the rich. It is this equality that they propose. And here we see the living things of all time, of today, of yesterday, of the distant past. So, will you criticize Marx for not trusting in the words that are so abused, for looking reality in the face? Ferdinand Lassalle said, “to say what exists is already a revolutionary feat,” because reality works for us because it contains explosive elements because history contains dynamite, truly revolutionary forces that blow up the old “obsolete” societies.

So, from the perspective of method, Marxism cannot be considered “obsolete.” It proceeds from the most modern ideas: movement, transformation, evolution, revolution.

Marx was horrified by emptiness, by the abstract, by words that could apply to everything and which explain nothing, by strong words exploited in order to hide small things or to hide even abominations.

The Class Struggle

The social base of Marxist theory is class struggle. Marx did not content himself (like the bourgeois sociologists) with this banality that consists of arguing that society is made up of individuals and not potatoes. He said, “No, it is not individuals that we should study in society, nor their needs; what must be studied is classes.” When you look at someone in the street and ask: “Who is he?” If we reply, “He is a man,” you reply, “That’s a bad joke, and you have no clue about the person you met.” But if we reply, “He is a man without work, he’s unemployed,” you are informed; if we reply, “That’s Ford, or Citroën,” immediately you know who you’re dealing with.

People still deny the existence of classes. The Times, in its headlines—its emptyheaded headlines—says, “Don’t speak of classes, that’s obsolete, the French Revolution surpassed that, it eliminated classes; all men are equal; Félix Faure was able to become President of the Republic; nothing can stop you from following your dreams; nothing is written in the Penal Code to prevent you, so classes have been eliminated.”

The Times forgets everything up to passenger classes on trains. It forgets, also, that there are even in Paris quarters for classes, and that, for example, in that in which I live, the one ironically called the Santé [Health] Quarter, mortality rates are multiple times higher than in the quarters of the rich classes. There are even class funerals, and so we promise capitalist society a first-class funeral.

Given the events since the war, it’s a macabre joke to say that class struggle does not exist.

We see in each country an organized working class; we also see the emergence of fascism. To go deeper, what does this mean? It is the class struggle of the highest degree. The dominant classes have learned something from Marx, and above all from the practice of class struggle by the revolutionary working class.

So long as governments have constituted police, the guardians of social peace, the guard dogs of property and society, we have contented ourselves with trusting the bourgeois state to defend class. But now, when through the evolution of temperaments, through permanent crises, we see that the state can be threatened under pressure from the masses, or placed in the impossible position of having to rigorously repress the new forces that arise; the dominant classes attract the unconscious from the middle and working classes, and pacify them with self-proclaimed anticapitalist watchwords, cry out at the capitalists, at the bankers—adding “Jews”—and organize themselves in a bluntly demagogic fashion. This is the defense of class, this is the strategy of class, and today these are new forces of terrorist repression available to the regular forces of the capitalist state. This is class struggle in its most violent form. Now, can we deny class struggle? Can we deny the claims of class?

Marx demonstrated this historic fact. He was not, furthermore, the first to demonstrate it. Guizot, the great historian contemporary to Marx, explained the development of the French monarchy by class struggle. It was the monarch who supported the bourgeoisie to diminish the influence of the nobility.

To try to understand modern history and explain, without the idea of class struggle, what is happening today in England, in Russia, in France, in Italy: it cannot be done. This is the indispensable factor for the comprehension of history.

Even our enemies begin to speak of classes. The terms “class” and “capitalist society” were once dismissed as absurd, as the bourgeois economists and theorists told us. They considered these to be socialist exaggerations. Now, everyone speaks of capitalist society or capitalism, and the fascists are forced to declare themselves anticapitalist.

The Marxist Political Economy

Now let us move on to Marxist political economy.

Marx did not begin his treatise on political economy with banalities like “everyone, to eat, to clothe themselves, etc., is obligated to produce.” No, Marx began by defining commodities, capitalist society, by explaining the law of value of commodities: the wealth of our society is not made up of goods meant to satisfy our needs, but of commodities, that is to say, goods meant to enrich a specific class. Marx examined, therefore, which laws determine the value of commodities. This is labor. In this, he agrees with the great classical economists. But Marx specified that it was not simply labor that determines the value of commodities. If you decided to transport a bag of flour on your back from Marseille to Paris, without traveling by rail, your labor would be useless and would not add anything of value to the flour. Labour only determines the value of a product when this labor is accomplished under normal technical conditions. The theory of value leads to the theory of capital gains, by which Marx demonstrated that capitalist profit is made up by labor unpaid by the capitalist to the laborer, by the exploitation of the commodity known as labor power.

Marx, in his analysis of capitalist society, formulated the theory of capital concentration, of the gradual expropriation and disappearance of the middle classes.

Are these ideas obsolete? Can Caillaux contest the concentration of capital? Are the trusts not modern, capitalist economic forms? And are all these capitalist forces not enough confirmation of the law of capital concentration? Is the most capitalist country in the world, the United States, not dominated by capitalist magnates, as Marx said; by those we call “kings”? Kings of oil, of rail, of automotive. There are even kings of pork and steak in Chicago. These are true monopolies of all the material wealth. These are the grand masters who dominate that immense country.

In France, there is still a mass of petty proprietors. But when we examine things up close, we see, for example, six big banks dominating all the markets—and even dominating the state. We can therefore not deny, in this era of billionaires, of big banks, of large stores, of great commerce, that the law of capital concentration exists.

The reformist Bernstein wanted to demonstrate that middle classes exist. He gathered up all the savings books of all the maids to say that there are still, in them, small capitalists. But Marx never claimed that owning a thousand or ten thousand francs made one a capitalist! To be a capitalist, according to Marx’s definition, one must use the means of production to exploit the labor of others and therefore have the ability to live without performing labor. This is not the case with a maid.

I believe that Caillaux has never read Marx, even while declaring Marxism obsolete. What is obsolete is this method that consists of refuting a great thinker without even reading them. Bernstein knew Marx, and he placed joint-stock companies at the forefront of his argument, by saying: there is no concentration of capital, as there are many millions of shareholders. He forgot nothing except to explain the mechanism of joint-stock companies, where he who has the largest block of shares is the true master of the joint-stock company, while the others are nothing but extras.

Everywhere, it’s the same thing. And when a crisis arises, when all the little “capitalists” are swept away, all that remains is the one with the largest block of shares; and if he’s running low on money, the capitalist state will come to his aid, as we’ve seen recently.

In the present era, especially after the war, can we speak of the disappearance of the middle classes? Let us ascertain this in each country. The radical or democratic parties in England, in France, in Germany are the representatives, the chargés d’affaires of the middle classes. If these classes were flourishing, they would dominate all the others; meanwhile, we see the British Liberal Party, with Lloyd George, reduced to impotence. In Germany, the democrats have vanished. We see but two blocs now: the bourgeois reactionary bloc on the one hand, and the proletarian revolutionary bloc on the other. In France, did the May 1932 elections give the lefts a total majority? They capitulated without a struggle to the bourgeois reaction. It is always the reactionary capitalists, the most powerful capitalists, who have the final say in the ministerial composition.

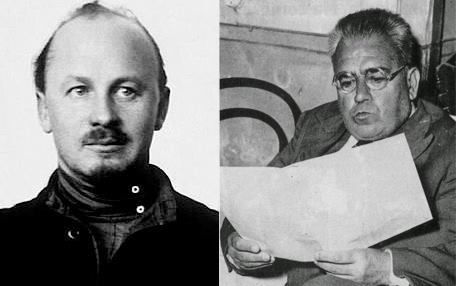

We have published side by side the portraits of Daladier and Mussolini, to demonstrate their resemblance. But when the Socialists proposed not even the socialist programme, but the most tepid of radical programmes to these democratic Mussolinis, the capitalists rejected them. Daladier complained, he practically cried, and faced with the intransigence of the reactionary capitalists he raised up his own lamentations as a plea.

Marx spoke of the anarchy of capitalist production. Is this not demonstrated by the Brazilian coffee thrown into the sea, or by the wheat we use to heat locomotives? In Brazil they throw millions of pounds of coffee in the ocean. They even spend a lot of money on this. So must we not recognize as true Marx’s analysis, which demonstrates that the capitalists are condemned to anarchy because they produce but for profit, for an undetermined market? Go, determine the extent of the global clientele! It is said that the capitalists are smart enough to determine, with their specialists, their publicists, their experts, the volume of the global market. But can we do it? Was the greatest crisis of the past years not produced in the countries of the trusts? It is precisely in America, land of the colossal trusts, that the crisis is the greatest.

This proves that capitalism cannot liberate itself from anarchy. It produces abundance. But on the other hand, there are 30 million unemployed, according to figures from the League of Nations—which is still not communist, by the way. Along with their families, this represents a population of 120 million at least. Is unemployment not a product of capitalism? This phenomenon was studied in admirable detail by Marx when he plotted out the immense riches created by modern technology, alongside a reserve army of unemployed dying of hunger beside the shops filled with commodities. Is, by chance, this theory of capitalist crisis an obsolete theory? One must argue in bad faith or be as ignorant as an academic to claim this.

A large number of Americans have discovered, in America, technocracy. They have demonstrated, with numerous statistical findings, the marvels of technology. They can make a factory work 24 hours without a single worker and augment 4000 times the productivity of certain jobs. But Marx, precise as ever, often cited the words of Aristotle—the greatest thinker of Antiquity—who, in order to justify slavery, said, “If we were to invent machines that could weave and do other work, we could leave slavery behind.” Marx loved to cite this, to demonstrate how we have realized the brilliant idea of Aristotle. We have achieved truly miraculous productivity; we have machines that can do anything, admirable machines, and this is a product of capitalism that we will not refuse. Marx even gave a eulogy of the historical mission accomplished by the bourgeoisie, which has led to the appearance of giant cities and modern mechanical production. He wrote this in 1847. If he saw the present miracles of production, what would he have said! But we contest that these technical marvels, these admirable machines, instead of creating social and individual wellbeing, serve but a category of privileged people, and are raised up against the workers. Each new machine represents another massacre of workers, thousands of workers thrown to the street, without work.

Capitalist rationale is the rationing of the proletariat. The more capitalist society is rationalized, the less you have of the means of existence. This is confirmation of Marx’s dialectic, which demonstrated that every society perishes from its own contradictions. He consecrated his life to the study of contradictions inherent to capitalist society, the abuses that the society fatally engenders. And it does not suffice to destroy these abuses, as the ignoramuses say, but rather it is the very source of these abuses that it is a question of destroying: capitalist society!

Marx demonstrated that all these social contradictions are inherent to the capitalist mode of production, to the fact that the means of production are monopolized by an oligarchy, concentrated in the hands of a minority who enrich themselves while the majority, the working class, can live only by selling its labor-power to these owners of the means of production.

It is this that Marx asserted. Is it not true? Are there means of combating the crisis other than destroying its very cause? What do the technocrats say? They want to maintain capitalist society, that is, the cause of the crisis, its very base, the source of the contradictions of society; and at the same time they claim to want to eliminate its consequences. But what would happen if the technocrats became the leaders? There would be an organized or coordinated society, but this would be subordinated to capitalist interests. At the head of society, and, in the place of capitalists, it would be great engineers and technicians who dominate, always with an eye towards exploitation; because, as long as you leave the proletariat in its state, as people deprived of the instruments of production, they will inevitably be slaves, whether of Ford or of his engineers. Nothing would change. Instead of plutocracy, there would be technocracy.

Furthermore, Saint-Simon anticipated the technocrats in a famous parable, which even earned him a lawsuit. He said, “The kings, the parents of kings, the generals, the ministers, all of these could disappear, and society would not disappear. But the technicians, that’s another matter.” He understood the value of engineers, of architects, of doctors. This is not new. This is, I repeat, America discovered in America by Americans. But instead of starting from a logical premise, and observing the profound reason for this capitalist anarchy, this contradiction between technical progress and social misery, the “technocrats” plug up their ears and shut their eyes in order to maintain the exploitation of man by man.

Marxist Politics

I will move on now to the last chapter: Marxist politics.

Marx, basing himself in the analysis of capitalist society, didn’t address goodwill or the supposed common interest. As he based his sociology on the existence of classes opposed to one another, with antagonistic interests, he understood that among all these classes, only the proletariat was a revolutionary class. This is logical. Having nothing to conserve, the proletariat does not have any interest in being conservative. They possess only their own labor power. They are therefore a revolutionary class. They have nothing to lose but their chains and everything to win, as Marx said at the end of the Manifesto. How is it that the capitalists could be revolutionary? Have you ever known capitalists who demand shorter workdays and higher wages? Never has the capitalist class declared that it wishes to eliminate property. There may be some rare exceptions who prove the rule but never has a class committed suicide.

Marx understood this, while the utopians like Charles Fourier worked to persuade the bourgeoisie to be intelligent and organize social harmony and cooperation. Others, like Robert Owen, who sacrificed millions for social reform, sent sincere, good-faith letters, supplications, to the conventions where monarchs met to take counterrevolutionary measures. He worked to persuade these monarchs that by adopting his project, they could avoid revolution. He worked to persuade the wolves to not eat the sheep. Naturally, he was mocked, and his supplications were never addressed.

Marx was not against political action. He did not place trade unionism, the economic action of the working class, in opposition to its political action. He understood well the role of the state, which he defined thus: “The state is an administrative council of the dominant classes, united to oppress the exploited classes, the dispossessed classes.” He added, “It is necessary to destroy this force, and let us give power to the proletariat—this is what we call the dictatorship of the proletariat. We must give state power to the proletariat in order to eliminate inequality, or rather to remove the monopoly over the means of production from the capitalist oligarchs.” According to Marx, it is necessary to end the domination of possessing classes, to expropriate the proprietors. And by what means, other than by revolution?

It’s from Marx that we get the term “parliamentary cretinism.” Marx was not against parliamentary action, though. He used “parliamentary cretinism” to describe those who believed that they could realise social transformation through such means. Now, parliamentary cretinism is surpassed by ministerial cretinism.

There are those who believe that, with good ministers, we can transform society. Marx denied this. One of the greatest crimes of German social democracy was having believed that with the aid of “parliamentary cretinism” and participation in the bourgeois state, they could change the social model. Of course, you know what state Hitler’s Germany now finds itself in.

Is this not topical today? Is the conception of the conquest of power by revolutionary force obsolete? Never has a people, never has a class obtained its liberation on its knees. It is time to stand up, to struggle, to spill our own blood if we want to attain our emancipation. We cannot avoid revolution by relying simply on millions of voices. In 1904, in Amsterdam, Bebel stood against the ministerial participation supported by the reformists, and demanded that we declare the working class a “party of revolution.” But defining revolution, that was another matter. He said at the same congress, “We are growing by millions of voices; when we have the majority, the bourgeoisie will be drowned, they will be an islet in an ocean.” We see today the “islet” in the person of Hitler and his hitmen.

Marx never, in all his work, employed revolutionary phraseology. The revolution, for Marx, was like an underground fire, smoldering beneath his theories. He examined the origins of revolution without searching for revolutionary phrases. The latter is the specialty of certain other categories of people. It was not Marx’s specialty, as he was preoccupied with establishing facts, which were able to reveal logical conclusions: organise the working class with the knowledge that it is a revolutionary class, that it is not to negotiate, but to fight, as Jules Guesde said. It follows that we should not become ministers of state, that is to say members of the administrative council of the dominant classes. How! You want to enter in this administrative council to look after the day-to-day business of the bourgeoisie? To provide another example of class collaboration, how can Blum declare in his debates and articles that we have no interest in the bankrupting of bourgeois society? However, Mirabeau himself, that bourgeois revolutionary descended from the nobility, understood that the bankrupting of the nobility was a necessary step in the advent of the bourgeoisie. And here, there are those who do not understand that the collapse of capitalism can serve the proletariat! Our intention, our historical “mission” is not, according to Marx, to save capitalism from its inevitable bankruptcy, but to organize and develop the consciousness of the proletarian class.

Yes, there will be suffering; but will there not be even more in the upcoming war? Are we not threatened with a war of extermination? Will the reformists as well as the revolutionaries not disappear in the storm? Can we have confidence in the dronings of the pacifists in Geneva? Has this not all gone bankrupt?

Marx predicted this, declaring that capitalism is at the root of every modern war, and Lenin, in turn, demonstrated that in the era of imperialism, war is inevitable. We have only to state the facts standing before us. We see the impotence of the League of Nations. Despite the confidence people put in the League of Nations at the beginning, it did not prevent the war in the Orient; and if tomorrow, Germany, faithful to the social developments in that country, wanted to occupy the Polish corridor and begin a war, could the League of Nations stop it?

Marxism is not Obsolete

Marx presented his economics against the classical economics of the bourgeoisie. What was the principal, fundamental director of bourgeois economics? “Leave us be, let us do as we like!” But is there anyone in the world who can accept this principle and admit that it’s really saying, “let us make war, let us inflict misery”? Is individualism not bankrupt?

There is the theory of the elites, adopted by Mr. Caillaux, the originator of the phrase “Marxism is obsolete.” The elites, well, they’re naturally Mr. Caillaux and his friends. Us, we say: “There is another elite, and that is the working class, which begins to think, to organize, to become a global force.” We already have the example of the USSR, and I ask my opponents, who were the sociologist, or statesman, or historian who foresaw the advent of the proletariat in the historic role it is playing today?

Marx and Engels foresaw this historic role of the proletariat, and this was particularly difficult in 1847, as the proletariat existed but as a social fact, not yet as an organized force conscious of its historic goal: the end of capitalism. Marx and Engels saw but the beginnings of the working class, but thanks to their ingenious analysis, to their dialectical materialist method, they foresaw the historic role of the proletariat.

We can critique the difficulties of a country making up one-sixth of the globe and boycotted by all the rest. But there is in this a fact that exists: that the proletariat conquered power, that it holds power and is victoriously building socialism.

Is the historic role of the proletariat obsolete? No, Marxism is not obsolete. It is living, and it will live everywhere!