Karl Marx’s own ambiguous and sometimes contradictory views on colonialism meant that the Second International would debate over the correct view on the matter. Donald Parkinson gives an overview of these debates, arguing that Communists today must unite around a clear anti-colonial and anti-imperialist program.

Today, when Marxism seems to be under constant intellectual assault, we hear the claim that Marxism is a Eurocentric ideology, that it is a master narrative of the European world. It could be tempting to simply dismiss this claim on its face. After all, most Marxists today live in the non-European and non-white world, inspired by the role Marxism played in anti-colonial struggles. Yet we should always pay attention to our critics, regardless of how bad-faith they may be. They can help us understand our own blind spots and weaknesses and better understand ourselves. As a result, we should take the question of Eurocentrism seriously and engage in a critical self-reflection of our own ideas. A closer look at both the works of Marx and the history of Marxist politics tells us that there were indeed Eurocentric strains in Marx’s thought. Yet through its capacity to critically assess itself Marxism has, to varying degrees of success, overcome its Eurocentrism to develop a true universalism, against a false universalism that only serves to cover for a deeper European provincialism.

Marxism developed in Europe as a worldview designed to secure the emancipation of the world from class society. This is the source of internal tension within Marxism: on one end there is the universalist scope of Marxism, an ideology designed to unite all of humanity in a common struggle. On the other end, there is the source of Marxism in the continent of Europe, an ideology that was shaped by the specific processes of capitalist development that propelled Europe into an economic power standing above the rest of the world. It would be foolish to simply dismiss charges that Marxism contains Eurocentric elements that exist in tension with its universalism. There is no better example of these tensions in Marxism than the different views on colonialism within the movement.

Colonialism in the history of Marxist thought served as a challenge for Marxism to overcome its own Eurocentrism. Within the works of Marx one can find different approaches to colonialism that could be read as apologetic to colonial expansion or firmly opposed to it, supporting the struggles of colonized people against their dispossession. As a result, the followers of Marx who formed the mass parties that came to be known as the Second International did not have a single position on colonialism that they could take from Marx. There was instead a series of often contradictory positions on colonialism within his work that provided justifications both for supporting colonialism and opposing it. There was also a theoretical heritage within Marxism, economistic developmentalism, that would be used to justify colonialism in the name of socialism.

To better understand these tensions in Marxism, we should examine Marx’s views on colonialism and the first major debates on colonialism in the Second International. These debates are an important part of a greater historical narrative, in which Marxism developed as an ideology in Europe and became the siren song of countless anti-colonial revolts against European domination. Marxism was able to overcome its initial Eurocentrism, but not without a struggle internal to itself and its intellectuals. In better understanding the history of this intellectual struggle, we can better identify the theoretical errors that held Marxism back from becoming a truly universalist worldview, which could serve as a political creed for the emancipation of the world, not only Europe.

Marx on Colonialism

To begin, it is necessary to look at Marx’s own views on colonialism and their development over his lifespan. Marx’s views on colonialism were never straightforward, and taken as a whole can be seen as inconsistent and contradictory, leaving room for interpretation. It is this openness for interpretation that allowed colonialism to be an open question for his initial followers. Within Marx one can find, on the one hand, a view of economic development and historical progress suggesting that European colonialism was a harbinger of progress, bringing the “uncivilized world” into “civilization” by laying the seeds for capitalist development and therefore proletarian revolution. And on the other hand, one can find in the later works of Marx the beginnings of an anti-imperialist and anti-colonial politics.

In his well-known Communist Manifesto, written in 1848, Marx comes across as almost a colonial apologist of sorts, pointing to the rise of the capitalist world market as an accomplishment of a historically progressive bourgeoisie, and colonialism as a means through which this world market is established:

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.1

Referencing “Chinese walls”, Marx strongly suggests that England’s First Opium War against China was in the long run historically necessary and progressive, bringing a “barbarian nation” into “civilization”. For Marx in 1848, colonialism wasn’t so much something to be condemned and battled, as it was part of a historical process through which capitalism would conquer the world and create the necessary pre-conditions for a communist future, with all nations passing through a similar route of development. However, with time, Marx’s views on the matter would develop.

After moving to London in 1849, Marx would take up a career as a journalist and wrote a series of articles on non-western societies. One of the first of these was the 1853 piece The British Rule in India. In this article, Marx expresses sympathy with the victims of British colonialism in India, while at the same time seeing British imperialism as essentially progressive, claiming that

“English interference, having placed the spinner in Lancashire and the weaver in Bengal, or sweeping away both Hindu spinner and weaver, dissolved these semi-barbarian, semi-civilized communities, by blowing up their economical basis, and thus produced the greatest, to speak the truth the only social revolution ever heard of in Asia.”2

Marx suggests that through its colonial process, the British are essentially bringing a stagnant and backward society into history, and only through its interference and disruption of this social formation can India become a real actor on the world stage of history. However, this one-sided view would not remain consistent in Marx himself. The conclusion to his 1853 series of articles on India, The Future Results of British Rule in India, would argue for a social revolution in Britain to challenge colonial policy and also point to the possibility of a movement for national independence from British rule. He would also condemn the “profound hypocrisy and inherent barbarism of bourgeois civilization” which “lies unveiled before our eyes, turning from its home, where it assumes respectable forms, to the colonies, where it goes naked.”3

Marx’s ambiguity here can be seen as a result of what the scholar Erica Benner calls a “two-pronged assault on the conflicting reactions of British MP’s to the government-sponsored annexation of ‘native’ Indian states.”4 On one side of this conflict were reformers who denounced the colonization as a crime pure and simple, while on the other end were those who saw colonialism as a historical necessity. For Marx, the former were ineffectual moralists while the latter simply apologists for bourgeois rule under the guise of patriotism. Marx sought to stake out a position between these two camps. To simply morally condemn colonialism seemed to suggest a return to a mythic pre-contact golden age, while to affirm the right of the Empire to annex India would be justifying naked bourgeois interests. By seeking out a position beyond this binary Marx sought to develop a position that would be able to reap the “benefits” of colonization while still looking beyond it.

In the latter years of the 1850’s Marx’s views on colonialism would develop remarkably in contrast to his earlier views. In his 1857-59 series of articles on China and the Second Opium War, any lauding of the progressive effects of colonialism in China is absent. Rather, Marx would focus on heavily condemning French and British colonialism, going so far as to gleefully report the British and French taking 500 casualties and mocking British editorialists who proclaimed their superiority to the Chinese. Marx would also espouse a more anti-colonialist position in his articles on the Indian Revolt of 1857-58, and in a letter to Engels in January, 1858 would tell his close intellectual and political partner that “India is now our best ally.”5

In the course of the 1850s, Marx would move from viewing colonialism as progressive to supporting anti-colonial uprisings. He would likewise support independence for Ireland from Great Britain and Poland from the Russian Empire, agitating for these positions within the First International and the British labor movement. Marx and Engels both would take the position that British workers must support the national liberation of Ireland in order to fight against anti-Irish chauvinism in the labor movement. This was a development from an earlier position that Ireland’s liberation would come through incorporation into a socialist multinational Britain.6 Rather than seeing the separation of Ireland as impossible, it was now inevitable if the unity of the labor movement was to be reached. Only after the separation of Ireland from the British Empire could a multinational socialist state be formed. The merging of nations into a socialist republic would have to occur on the terms of the Irish, not the British:

The first condition for emancipation here – the overthrow of the British landed oligarchy – remains an impossibility, because its bastion here cannot here be stormed so long as it holds its strongly entrenched outpost in Ireland. But once affairs are in the hands of the Irish people itself, once it is made its own legislator and ruler, once it becomes autonomous, the abolition there of the landed aristocracy (to a large extent the persons as the English landlords) will be infinitely easier than here, because in Ireland it is not merely a simple economic question but at the same time a national question, for the landlords there are not, like those in England, the traditional dignitaries and representatives of the nation but its morally hated oppressors.7

From this one can see the development of the Leninist position of the right of nations to self-determination. This position was able to condemn colonialism forthright, without resorting to a moralistic fetishization of traditional pre-colonial society. Marx linked the liberation of the working class in the metropole with the national liberation of the colony, creating a vision of revolution that put agency in the hands of colonized rather than resigning them to passive objects to be liberated by the working class of the more advanced nations. Engels would continue this thesis after the death of Marx in regards to India and other colonies, stating that the proletariat in the metropole could “force no blessings of any kind upon any foreign nation without undermining its own victory by so doing.” Socialism could not be brought to colonized people through imperialist bayonets; instead the colonies were to be “led as rapidly as possible to independence.”8

From this evidence it is clear that Marx (and Engels) began with a more ambiguous and even positive view of colonialism, and moved to a more critical view, developing the beginnings of an anti-colonial Marxism. Yet these anti-colonial positions were mostly found in fragments throughout letters rather than systematized in popular agitational material. As a result, when developing a politics based on the views of Marx, his followers could selectively pick out specific passages from his works to bolster positions that were apologetic of colonialism. While we should be critical of such a scholastic approach to politics, there can be no doubt that many of the Marxists of the Second International justified their positions on readings of Marx.

Bernstein vs. Bax on Colonialism

In 1889 the foundation of the Second International saw the beginning of an era of Marxism without Marx, and in 1895 without Engels. The wisdom of the founders would soon no longer be a guiding light for the movement, and a new generation of intellectuals would have to carry the torch. The work of Marx and Engels, while providing a theoretical framework for questions like colonialism and imperialism, hardly provided a full, all-encompassing answer to properly deal with these questions. A single party line that could be applied wasn’t developed. It would be up to debate and deliberation within the union to determine the correct way forward.

In 1896, a year after the death of Engels, the debate would flare up, the two most prominent voices in the dispute being the German Eduard Bernstein and the British Belfort Bax. These debates were triggered by rising tensions between Armenians and the Sultan’s regime in Turkey, with Germany poised to intervene in the Armenians’ favor. In his 1896 article German Social Democracy and the Turkish Troubles, Bernstein would argue strongly in favor of supporting the Armenians, using the rhetoric of more “advanced” nations having a historic duty to “civilize savages”. His arguments would be hard to distinguish from the rhetoric of the colonialists themselves, claiming:

Africa harbors tribes who claim the right to trade in slaves and who can be prevented from doing so only by the civilized nations of Europe. Their revolts against the latter do not engage our sympathy and will in certain circumstances evoke our active opposition. The same applies to those barbaric and semi barbaric races who make a regular living invading neighboring agricultural peoples, by stealing cattle, ect. Races who are hostile or incapable of civilization cannot claim our sympathy when they revolt against civilization.9

Bernstein would of course aim to give his blatant colonial apologism a humanitarian aspect, adding, “We will condemn and oppose certain methods of subjugating savages.”10 Yet in the end Bernstein upheld that colonialism was progressive and should be supported, that it was part of a historical process in which backwards societies would be brought into civilization. He therefore argues for German support in the cause of the Armenians against Turkey using this line of thought.

Belfort Bax, an SDF11 theorist who, like Bernstein, was also controversial, would respond to Bernstein with the harshly titled Our German Fabian Convert: or Socialism According to Bernstein. Beginning his response by accusing Bernstein of ‘philistinism’, Bax would go on to attack Bernstein’s arguments on three fronts. The first was that socialism was not the equivalent to what the bourgeois colonialists called civilization but rather its negation, that the “civilization” imposed on colonized populations was nothing of the type socialists should support.

In his second point, Bax would argue that while it was correct that capitalism was a precondition for socialism, it was not necessary for capitalism to be spread to every single corner of the earth:

“The existing European races and their offshoots without spreading themselves beyond their present seats, are quite adequate to effect Social Revolution, meanwhile leaving savage and barbaric communities to work out their own social salvation in their own way. The absorption of such communities into the socialistic world-order would then only be a question of time.”12

This would tie into the third part of Bax’s rebuttal of Bernstein, which was that rather than spreading capitalism to create the preconditions of socialism, colonialism actually gave capitalism a longer lease on life. Capitalist overproduction, an expression of its own internal contradictions, was the motor force behind the drive for capitalist nations to compete for colonial territories and engage in colonial conquests. By opening up new markets for commodities and cheap labor, capitalism would “soften” its internal crisis tendencies, hence delaying the “final crisis” that would allow for its revolutionary destruction. Hence Bax would make the direct opposite argument as Bernstein: rather than supporting colonial ventures, albeit in a “humane” manner, Social Democracy should support all resistance movements against colonialism regardless of how reactionary they may be, as their victory would increase the internal contradictions of capitalism and speed up its demise.

Bernstein’s next response to Bax, Amongst the Philistines: A Rejoinder to Belfort Bax, would primarily repeat his prior arguments: that “savage races” deserve no sympathy from socialists despite the need for condemning the most brutal forms of colonial subjugation. What exact methods of subjugation were acceptable and which weren’t isn’t clarified by Bernstein, the only clear part of this argument being that subjugation was necessary. This time Bernstein would also make references to the works of Marx and Engels, claiming that Bax was an idealist who was ignorant of what their own positions would have been on this matter. This reveals how the contradictory positions on colonialism in the writings of Marx would leave these issues up to open debate.13

The next round of debates between Bax and Bernstein would resume in late 1897, with Bax’s Colonial Policy and Chauvinism. The arguments in this piece show a development in thought in response to the positions of Bernstein, which Bernstein presented as authentically Marxist due to his upholding of capitalism as a progressive force based on free-labor spread through colonialism. Responding to this notion, Bax would argue that the labor regimes in the colonized nations were not in fact progressive regimes based on “free” waged labor, but a system which “combines all the evils of both systems, modern wage-labor and caste-slavery, without possessing the decisive advantage of the latter.”14 He would also claim that the chauvinism associated with the Anglo-Saxon domination which came with colonialism would be an obstacle to a future brotherhood of humanity, by bringing about a world culture dominated by a single ethnic group. This point would be buttressed with a claim that his stance was not merely a moral one based on abstract notions of human rights, but rather one which was based on a concrete strategy to overthrow capitalism.15 Also of importance is to note that Bax would also draw from the writings of Marx and Engels to make these arguments, countering the use of their arguments by Bernstein.

Bernstein would respond to these arguments with a two-part article, The Struggle of Social Democracy and the Social Revolution. Here he accuses Bax of seeing no deprivations and oppression where capitalism doesn’t exist, essentially holding onto a romantic view of non-capitalist societies. Countering Bax’s argument that the labor regimes introduced in the colonies aren’t progressive and actually based on free labor, Bernstein makes the argument that these initially harsh and un-democratic regimes will naturally evolve into democratic ones as if this tendency is inscribed into capitalism itself. Regardless of the cost, for Bernstein “the savages are better off under European rule.”16

With regards to Bax’s concerns about Anglo-Saxon cultural dominance, Bernstein simply argues that this is countered by France and Germany stepping up to join in as competitors in colonialism. Even if this wasn’t the case, Bernstein sees the cultures victim to colonialism as having no national life of their own, hence being better off assimilated. Not only is this argument obviously chauvinistic in acting as if only Europeans have an authentic culture, but it acts as if the same critique that Bax makes wouldn’t also apply to European dominance and not just Anglo-Saxon dominance.17

Also key to Bernstein’s reply to Bax is his rebuttal of the claim that opposing colonialism will hasten the “final crisis” of capitalism. Bernstein argues against the idea that capitalism will collapse due to its internal crisis tendencies, and argues instead for gradually reforming capitalism to transform it into socialism. It was through this argument that Bernstein would find himself in a political camp that completely diverged from the revolutionary Marxism of the SPD majority, his camp in the party being labelled as “revisionists”.18 Bernstein began from a position of defending colonialism on orthodox Marxist grounds, only to find himself exiting orthodox Marxism in the process.

Karl Kautsky on Colonialism

Karl Kautsky, possibly the most well-respected intellectual voice in the Second International, would initially side with Bernstein in the debate, calling Bax an idealist.19 Yet as the debate progressed Kautsky’s views on colonialism would develop so as to lean more in the direction of Bax’s position in its political conclusion, and point official SPD policy in a more anti-colonial direction. By the time of the 1898 Stuttgart Conference, Kautsky would openly condemn Bernstein’s views. Despite his condemnation of Bernstein, a closer look at Kautsky’s writings on the topic of colonialism reveal a degree of moral ambiguity.

In his 1898 article Past and Recent Colonial Policy, Kautsky lays out his basic framework for understanding colonialism. His argument rests on two basic claims. The first is that industrial capitalists do not have a material interest in colonialism, and instead favor a policy of free trade referred to as Manchesterism. For Kautsky, Manchesterism is not only based on laissez-faire economic policy but also “preaches peace”.20 To the extent that industrial capitalists are interested in colonialism, it is for export markets, which do not always align with colonial policies. Following this claim, Kautsky makes the argument that the class basis for colonialism is basically pre-capitalist aristocratic elites who form the military/colonial bureaucracy and finance/commercial capital. Colonialism is not a policy of the historically progressive industrial capitalist, but a reactionary and backwards policy based on the interests of classes antagonistic to industrial capital. In Kautsky’s analysis:

“the same industrial capitalist, who at home will resist any worker protection law without any qualms, and have no compunction about whipping women and children in his bagnio, becomes a philanthropist in the colonies – an energetic foe of the slave trade and slavery.”21

To explain Germany’s rising interest in imperialism, Kautsky claims that it is to maintain competition with the French and British, whose colonialism is fueled by the pre-capitalist elites and financial capitalists. This argument essentially turns Bernstein’s on its head, countering that colonialism is not a product of capitalism’s progressive tendencies but rather a holdover of reactionary classes. However we can find inconsistent aspects of this argument. For example, he ascribes to settler colonies “based on work” a progressive quality in contrast to colonies based on pure rent extraction. This not only confuses his own argument but reveals moral blindness to the genocidal nature of settler colonialism.22 In 1883 Kautsky would make a similar argument, counterposing the “progressive” and “democratic” colonialism of the USA and England to that of Germany.23 This is in sharp contrast to the arguments made by Bax, which while not purely based on appeals to morality, are strongly based in a moral condemnation of all colonialism. This attitude toward settler-colonialism is also apparent in his 1899 article The War in South Africa, which simultaneously argues for supporting the Boers against the British Empire and asserts, “We, by contrast, condemn modern colonial policy everywhere.”24

Official Resolutions

The SPD conference in Mainz on September 17-21, 1900 would see the party take up an official resolution on imperialism. Rosa Luxemburg would emerge as a powerful anti-colonial voice, condemning the war against China while urging for active anti-war agitation. The mood of the conference was overall anti-imperialist, with delegates condemning Germany’s intervention in the war against China. Contrary to the views of Bernstein, the resolution passed would state that military conquest was an all-out reactionary policy:

“Social Democracy, as the enemy of any oppression and exploitation of men by men, protests most emphatically against the policy of robbery and conquest. It demands that the desirable and necessary cultural and commercial relations between all peoples of the earth be carried out in such a way that the rights, freedoms and independence of these peoples be respected and protected, and that they be won over for the tasks of modern culture and civilization only by means of education and example. The methods employed at present by the bourgeoisie and the military rulers of all nations are a bloody mockery of culture and civilization.”25

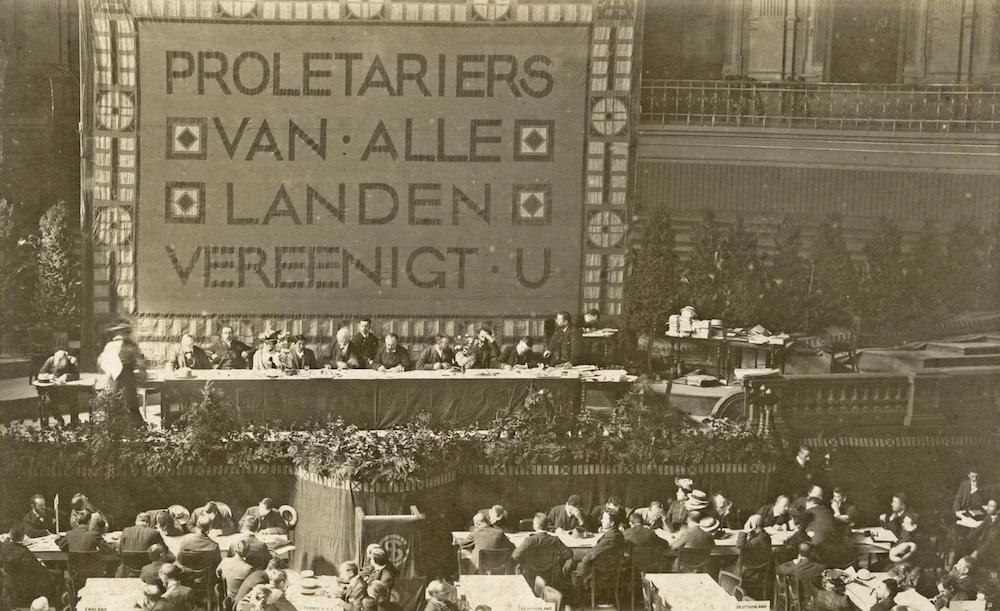

Ultimately it would be the positions more aligned with those of Kautsky and Bax that would win out as the official policy of the SPD. Bernstein would represent a pro-colonialist minority in the party, with some members of the International like Henriette Roland Holst claiming that the mere existence of this minority in the party shouldn’t be tolerated. Days after the Mainz conference the entire International would have a conference in Paris and a similar resolution would be passed, this time with Luxemburg authoring a resolution that not only condemned imperialism but described it as a necessary consequence of capitalism’s newest contradictions.26

The SPD’s Dresden Congress in 1903 and the Sixth International Congress in 1904 would further affirm an anti-imperialist stance. Yet while international congresses were of symbolic importance to the Social Democratic movement (seen as “international workers’ parliaments”), one must take into account the federal structure of the party. Each national party was ultimately autonomous in its decision-making authority, being left to itself to make its own programs and tactical decisions. The congresses were taken seriously by parties but ultimately no central body had the authority to enforce their decisions until the International Socialist Bureau (ISB) was formed at the Paris conference in 1900. Even then, the actual authority of the ISB was ill-defined, and the tendency towards autonomy prevailed. This would mean that parties in the International primarily saw themselves as national parties who served workers on a national basis rather than sections of a single world party.27 The extent to which resolutions would actually be binding on parties was therefore very ambiguous.

Stuttgart Congress

In 1907 the SPD would face a disappointing loss in the electoral campaign known as the Hottentot elections. The Hottentot elections occurred in the context of a pro-colonial nationalist fervor caused by the German colonial war and genocide in South-West Africa, where approximately 65,000 Hereros were massacred in the period from 1904-1908. While the number of eligible voters to the Reichstag election had risen significantly (76.1% in 1903 to 84.7% in 1907), the SPD would lose almost half of its delegates in the Reichstag (81 seats to 43 seats).28 Expecting that more eligible voters would mean more electoral success, the results of this defeat would throw the SPD into a period of doubt and reignite debates over colonial policy.

According to Carl E. Schorske the districts the SPD had maintained in the elections were primarily the working class dominated ones. The section of the electorate lost was the salaried professionals and small shopkeepers, who had fallen prey to the nationalist fervor of the German campaign in South-West Africa. According to Kautsky, the bourgeoisie had promoted the future colonial state as a more attractive alternative to socialism for these strata, something Social Democracy had greatly underestimated. The right wing of the party would respond by asserting that excessive radicalism had cost them votes; the more left-wing elements would point to the Hottentot election as proving the unreliable nature of this “petty-bourgeois” stratum. The radicals in the party therefore saw this as a reason to increase attacks on nationalism and colonial policy while the rightists saw it as a reason to push for a softer stance on colonial policy.29

Alexander Parvus, belonging to the left-wing of the party, would write an in-depth study of the colonial question in response to the Hottentot failure, Colonies and Capitalism in Twentieth Century. Unlike Kautsky’s 1898 pamphlet, Parvus would place colonialism in the context of the contradictions of the modern capitalist system, with overproduction, the falling rate of profit and the merging of production and exchange in finance capital as the motor force behind colonial policies, rather than pre-capitalist elites.30 He cited the increasing imperialist policies of the British Empire as symptoms of its decline as a hegemonic world power, scrambling to hold onto supremacy as it collapses.31 From this theoretical study, Parvus came to the conclusion that colonial policies are symptoms of the decline of capitalism that will present the proletariat with an opportunity for revolutionary action. No political support for colonial policy of any kind was acceptable in Parvus’ view.32

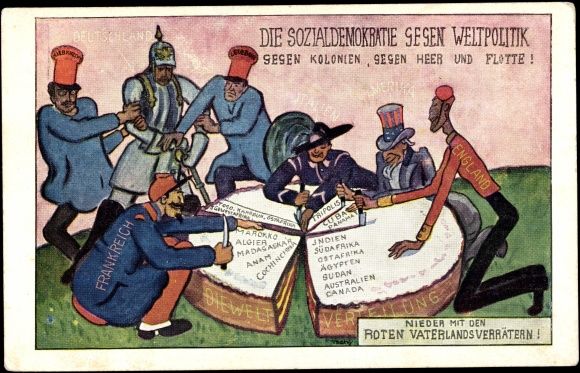

Following the Hottentot failure was the Stuttgart Conference of 1907. This conference would see the colonialism debates resume, this time with a victory for the right. The conclusions made by Parvus, that colonialism was a symptom of capitalist crisis that must be combated with revolutionary action, would be rejected by the majority of conference delegates. In a shift to the right, Luxemburg’s anti-imperialist resolution from the 1900 congress would be dropped and replaced through a process of contentious debate.

One of these debates was between two delegates of the German party, Eduard David and George Ledebour. David quotes August Bebel, a highly respected leader of the party, as saying “it makes a big difference how colonial policy is conducted. If representatives of civilized countries come as liberators to the alien peoples in order to bring them the benefits of culture and civilization, then we as Social Democrats will be the first to support such colonizing as a civilizing mission.”33 The fact this quote is from August Bebel, one of the most important leaders of the Social Democratic movement, is revealing. It shows that for many Social Democrats, opposition to colonialism wasn’t opposition to European supremacy and was still premised on the legitimacy of a European civilizing mission. It was merely the methods of colonialism that were opposed, methods that were to be replaced by peaceful ones that would make Europeans welcome missionaries of progress.

Ledebour would respond by polemicizing against Bebel as well as David, arguing that Bebel’s position asserted the possibility that colonial policy could be anything other than the existing horror and inhumanity that it was. Rather than calling for a more “humane” colonialism, he says that only the resistance of the exploited can lessen the brutalities of colonialism. After Ledebour spoke, a delegate from Belgium, Modeste Terwagne, would argue that if the occupation of the Congo were ended that “industry would be seriously damaged” and that “men utilize all the riches of globe, wherever they may be situated.”34

Ledebour and a Dutch Socialist, Hendrick van Kol, would draft a resolution in compromise with the socialist colonizers who condemned existing colonial policy while neglecting to condemn colonial policy under capitalism in general. Terwagne would introduce an amendment that affirmed the potential for a socialist colonial policy that acted as a civilizing force, while David would add another amendment saying that “the congress regards the colonial idea as such as an integral part of the socialist movement’s universal goals for civilization.”35 David’s amendments was rejected and Terwagne’s was incorporated in the final draft which was accepted by a majority of the congress:

“Socialism strives to develop the productive forces of the entire globe and to lead all peoples to the highest form of civilization. The congress therefore does not reject in principle every colonial policy. Under a socialist regime, colonization could be a force for civilization.”36

While the resolution also contained commitments for parliamentary delegates to “fight against merciless exploitation and bondage” and “advocate reforms to improve the lot of the native peoples” it failed to reject colonialism as such and instead aimed to reform the existing colonial occupations. This turn to the right disgusted Luxemburg, Parvus and Kautsky. However, the turn towards what was essentially a pro-colonial stance was a product of democratic deliberation, a process that could be reversed through open debate. By the end of the conference, Kautsky was able to build up a bloc of support that would defeat the original resolution by a vote of 128 against 108, with 10 abstentions. Replacing the original resolution would be a resolution that would state that the congress “condemns the barbaric methods of capitalist colonization” and claim “the civilizing mission that capitalist society claims to serve is no more than a veil for its lust for conquest and exploitation.”37

While an anti-imperialist motion did pass, 128 against 108 was hardly a vast majority of delegates. Russian Social Democrat Vladimir Lenin believed this to be a sign of growing opportunism within Social Democracy, one that needed to be battled against with vigilance. The Stuttgart conference “strikingly showed up socialist opportunism, which succumbs to bourgeois blandishments” and “revealed a negative feature in the European labour movement, one that can do no little harm to the proletarian cause, and for that reason should receive serious attention.”38 Social Democracy was not guaranteed to stick to a strict anti-imperialist platform, and such a stance would have to be battled for in the halls of congresses and in theoretical debates.

Debates on colonialism and imperialism would continue in Social Democracy, reaching an apogee when a majority of SPD Reichstag delegates would vote for war credits at the beginning of World War One, followed by the majority of other Second International parties. Ultimately Lenin’s fear of growing opportunism was proven correct. However, while one could assume that the Social Democrats who voiced opposition to colonialism most consistently would be those who vigorously opposed the war, anti-colonialists like Parvus and Belfort Bax would find themselves amongst the ‘social-patriots’ who rallied behind the war. Arguments for supporting the war would vary. In the case of Parvus it was his conclusion that it was necessary to defend the progressive German state against reactionary Czarism that led him to rally behind the Kaiser.39 If support or rejection of WWI was the ‘final test’ for Social Democrats, positions in the debates over colonialism ultimately would not serve as predictors for who would pass.

Conclusion

It would take the October Revolution, with its radical approach to the national question and solidarity with the struggles of colonial peoples, to truly establish an anti-colonial and anti-imperialist orthodoxy in Marxism. Lenin’s anti-colonial Marxism would inspire national liberation leaders in the colonies like Ho Chi Minh to align with the International Communist movement and deal a blow to Marxist Eurocentrism. While a blow was dealt, it wasn’t quite fatal, as European chauvinism would still haunt Marxist parties throughout the 20th Century, the most famous example being the French Communist Party’s refusal to support Algerian independence at the most crucial moment. In these instances, Euro-chauvinists were continuing an unfortunate tradition within Marxism that contested for legitimacy in the Second International using the writings of Marx himself.

The pro-colonial positions found both in Marx and in the Second International have a common theoretical basis that can be identified as Eurocentrism. According to Samir Amin, a key theoretical backdrop to the ideology of Eurocentrism is economism, defined as the view that “economic laws are considered as objective laws imposing themselves on society as forces of nature, or, in other words, as forces outside of the social relationships peculiar to capitalism.”40 Eurocentric economism reifies economic development as an inevitable process that occurs as long as “cultural” factors don’t stand in the way. It sees the uneven development of the world and the backwardness of the periphery as a product of the specific cultures of these societies being inferior to that of Europeans, barriers to economic progress that must be broken down. In contrast, the scientific socialist view sees economic development as a process contested by class struggle and the role of imperialism in reproducing the core/periphery division

In the Eurocentric ideology, the European world is seen as a world of wealth due to its unique culture while the rest of the world is held back by its culture (Asiatic stagnation for example) and only progresses to the extent it copies Europe. History is a progressive march towards modernization, and “it becomes impossible to contemplate any other future for the world other than its progressive Europeanization.”41 The future is shaped and defined by the West, which has everything to teach the rest of the world and nothing to learn from it. As a result, Western capitalism stands as a model for the planet, its mode of development universal for all countries and only held back by internal backwardness when this development fails to take hold. This chauvinist ideology took hold over Bernstein and even Marx at times, seeing the spread of colonialism as a progressive process that would enforce the development of stagnant societies.

According to the ideology of developmental economism, if not for the backwardness of the non-European world the development of capitalism would ultimately homogenize the world. Four-hundred years of global capitalist development has shown the world still heavily divided, not only between bourgeois and proletariat but between core and periphery nations. Capitalism is dominant in almost every country today, and the uneven development of the world still haunts the periphery. Bernstein’s vision of colonialism bringing capitalist “civilization” to the world has come to pass. Yet imperialism still ravages the world, creating what John Smith calls the super-exploitation of the global south by the developed capitalist nations. Capitalism has spread worldwide, but it has formed a global division of labor where the post-colonial proletariat labors for starvation wages to produce super-profits realized in the imperialist countries. According to Smith,

“…the very processes that produced modern, developed, prosperous capitalism in Europe and North America also produced backwardness, underdevelopment, and poverty in the Global South…the accelerated spread of capitalist social relations among Southern nations has been far more effective in dissolving traditional economies and ties to the land than in absorbing into wage labor those made destitute by the process.”42

The historical verdict seems to have been made in favor of the arguments of Bax and the anti-imperialists rather than Bernstein. Yet we must not pretend that this debate is merely of historical importance. Today we face an imperialism more based in systematically enforced economic underdevelopment, which is maintained through imperialist police actions. Rather than direct colonialism, it is primarily economic imperialism of the more informal kind that devastates the world. As a result, the defenders of imperialism amongst the left come in different forms than the likes of Bernstein. They are not the colonial apologists of old but advocates of US intervention as progressive in certain situations or those who refuse to be critical of social democrats who vote for imperialist war budgets. There are also those who refuse to take up demands for the deconstruction of settler-colonial states, like the United States, and the national liberation of those still under settler-colonial occupation, in the name of focusing on bread-and-butter demands. As the socialist movement develops, we must learn from the failures of the Second International to clearly establish an anti-colonial and anti-imperialist position in its ranks, which exists not only on paper but in the class awareness of the rank and file.