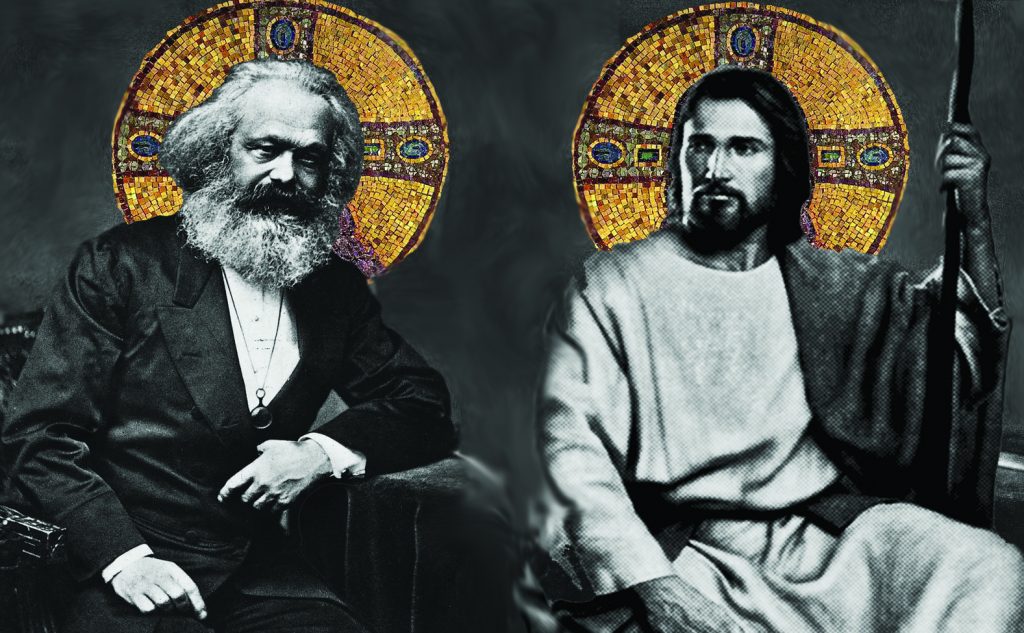

Lydia Apolinar, Alexander Gallus, and Ryan Tool pay tribute to the revolutionary and plebeian origins of Christianity.

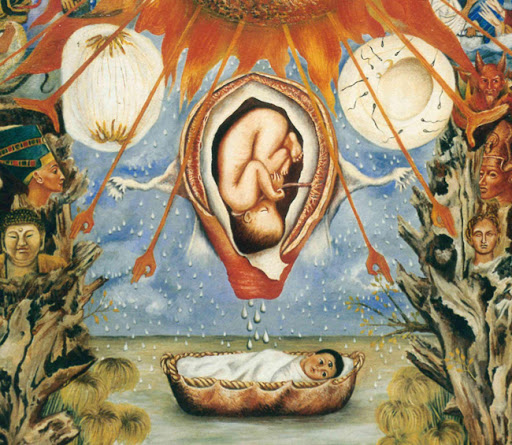

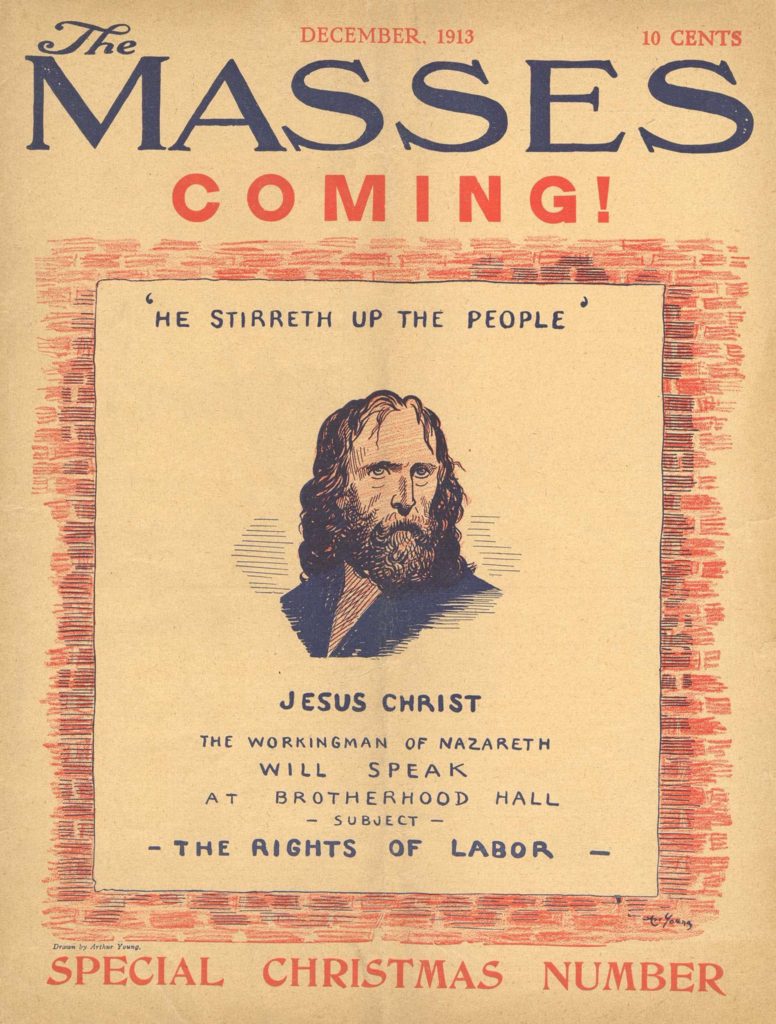

A total of 2 billion people will celebrate the holiday of Christmas this year, including over 90% of Americans. Two thousand and twenty years, according to the now universal Gregorian calendar, have passed since the birth of Jesus Christ in the Roman-occupied Kingdom of Judea. For Marxists, matters of religion have never been trivial, not least because many of the workers that must be reached with the ‘good news’ of communism retain religious faith. The doctrine of Christianity has been distorted throughout history by the ruling classes, and a fight to clarify its true revolutionary origins should be seen as important in the struggle for the popularization of scientific socialism.

One thing that is clear about the Bible is that it is full of contradictions. From Paul’s initial rendering to its modern interpretations, which often completely ignore the more radical biblical concepts, there has been an extended drift away from the working-class origins of the Jesus movement. Less focused on relaying accurate historical accounts, the Church’s own historians’ main focus was on effectiveness and not truth. Peter Wollen’s interesting 1971 article, republished yesterday in Sidecar, Was Christ a Collaborator, argues that Jesus was no revolutionary but rather a collaborator with the Romans and a supporter of slavery; this seems not only contradictory with the many original scriptures, but the makeup of the early followers of Christ themselves, many of whom were former slaves, guerrilla fighters, and of the poor. Wollen bases this view on the “numerous [recorded] parables” handed down over time. For as many scriptures as you can find of Jesus and the early Jesus cult promoting a life lived in the communist fashion, you can find just as many telling people to be good slaves to their masters and subjects of their ruling state. Build the communist community but “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s”1 and make peace with the Roman oppressors.

So many contradictions, interpolations, and cherry-picked quotes from a vast body of work can make one see in the holy texts whatever is convenient to one’s own class position or worldview. Much like the many different sects of communists and socialists today, the dissident Jewish religious sects in Ancient Rome would spend much of their time arguing about very small theoretical minutia, such as: What is the essence of the Holy Trinity? Are they all separate but equal parts of God, like the U.S. branches of government, or are they all just one thing? One wins the argument by how many Biblical scriptures can be shouted at the opposition, while in the end coming to everything and nothing at the same time.

To really understand the Jesus movement one needs to look closely at the historical period surrounding the events. As far away in time as it was, the first century AD is more similar to the world today than one might initially think: a vast empire ruled by the propertied classes, wantonly dominating other peoples, faced with the resistance of the plebeian classes, and particularly of colonized people. Rome was an empire that stretched from Portugal in the West to Turkey in the East. The Germanic hordes lay across the Danube, Roman units fought against the rebellious Scots and Northern tribesmen of Britain, while more storms were brewing in Jerusalem. Roman society was in a constant battle to expand its territories and further exploit their conquered peoples, mainly through enslavement and taxation. Jerusalem was at the center of the Jewish people’s struggles, although many Jews lived abroad in places like Alexandria (where about 25% of the population was Jewish) where there were also Jewish rebellions. Much like the modern left, Jewish religious organizations were marked by their countless splits and sectism. In the Talmud one can even find a quip that resembles a joke about the modern left: “Israel did not go into captivity until there had come into existence 24 varieties of sectaries”.2

Of course, the sects’ differences in philosophies masked the real differences in the social relations between people. Take as an example the differences between the zealots, Pharisees, Essenes, and Sadducees. While the lower classes were centered around the former three, the minority upper class was centered around the powerful Sadducees. The poorest sects around the zealots and Essenes had a philosophy that the will of the people was unfree. Being alienated and downtrodden by society, they felt whatever happened to them, bad or good, was predetermined by God and felt as if they had no control over their lives.

The Pharisees, who comprised a mixture of plebeian/peasant base and what could be considered a middle class, had the view that the will was free but followed a predetermined path. Sadducees, who made up almost exclusively a rich, powerful clerical ruling class based around the Temple in Jerusalem, thought the will was free and blamed the lower classes under their feet for being in their position because of some moral failing. Using the same foundational texts, different ideological groups coinciding with different social classes come to very different conclusions.

The problem only gets bigger when faced with the fact that the New Testament is a collection of prophecies, parables, fables, speeches, etc., that were written decades after the supposed events happened. Due to the proletarian nature of the original community, nothing would be written down for years and would only travel by word of mouth until those with upper-class backgrounds started to join the Jesus religion. Even then, the later versions of the earlier stories written down started to have upper-class ideology seep into them. For instance, Karl Kautsky in his Foundations of Christianity calls the book of Matthew the “Book of contradictions”, and contrasts it with the earlier more revolutionary scriptures. Any sense of class hatred towards the rich was revised and stamped out. In the earlier book of Luke, Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount reads:

“Blessed be ye poor: for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are ye that hunger now: for ye shall be filled. Blessed are ye that weep now: for ye shall laugh … But woe unto you that are rich! for ye have received your consolation. Woe unto you that are full! for ye shall hunger. Woe unto you that laugh now! for ye shall mourn and weep.”

The Sermon on the Mount according to the later book of Matthew, however, says:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven … Blessed are they, which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.”

Blessed are the poor turns into the poor in spirit, and blessed are the hungry turns into blessed are those that hunger for righteousness. And all of that woeing unto those that are rich? Matthew seems to have conveniently forgotten about that part of Jesus’s speech. Revisions such as these thoroughly corrupted and in fact inverted the message of the original community. The concept of “morality” itself thereby morphed from a gospel of social revolutionary critique and struggle against palpable and earthly conditions, into a critique of the virtue or sin of the individual.

Whereas some atheist, agnostic, and deist thinkers, notably Bertrand Russell, have questioned the existence of Jesus as a historical personage, Jack Conrad maintains that there were many “saviors, or messiahs (i.e. ‘christs’ in the Greek tongue) in 1st century Palestine”. Considering the tumultuous circumstances of the century, which featured a tremendous Jewish revolution in AD 66, this makes sense. Jesus likely was one among many– and perhaps an amalgamation of several such leaders. The important thing is that Jesus was not an isolated individual with unprecedented claims of being the Messiah; the kind of apocalyptic revolutionary movement he led was one of many that emerged amidst increasingly volatile social conditions.

In fact, as the English historian Edward Gibbon writes in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, pagan and Jewish sources contemporary to the time of Jesus found him unworthy of mention. Gibbon writes that “at Jesus’s death, according to the Christian tradition, the whole earth, or at least all Palestine, was in darkness for three hours. This took place in the days of the elder Pliny, who devoted a special chapter of his Natural History to eclipses; but of this eclipse he says nothing”.3 Instead, historians like the pro-Roman Jewish aristocrat Flavius Josephus lumped Jesus and his followers, the Nazoreans, in with countless other left-wing Jewish sects he referred to as “bandits” and “brigands”.4

Jerusalem was the center of Jewish life because of Solomon’s Temple. Jews from across the Roman Empire sent caravans of gold, silver, animals to be sacrificed, and whatever else they could as an offering to the Temple. The Temple was ruled by the high priests who were almost exclusively of the Sadducee mindset. They were mostly puppets in bed with the Romans. Although they were strongly attached to their identity as Jews, and in an abstract sense opposed to Roman rule, the threat from below of popular rebellion of the apocalyptic, communistic sects of the Jewish poor were more threatening to the aristocratic Sadduccees than the Romans were. In practice, this aristocratic priestly class was rightly regarded as complicit with the Roman oppressors by the zealots/Sicarii and what would later become the Nazoreans, the revolutionary grouping around Jesus. While a common laborer might not see much to lose in a rebellion against Rome, the high priests had their lives along with their wealth and influence to consider. According to Jack Conrad’s 2013 book Fantastic Reality, around 1500 priests received the tithes, with a smaller portion receiving the lion’s share of them.5 Collaboration with the Romans was an evil that they readily accepted in the face of popular rebellion from the lower classes.

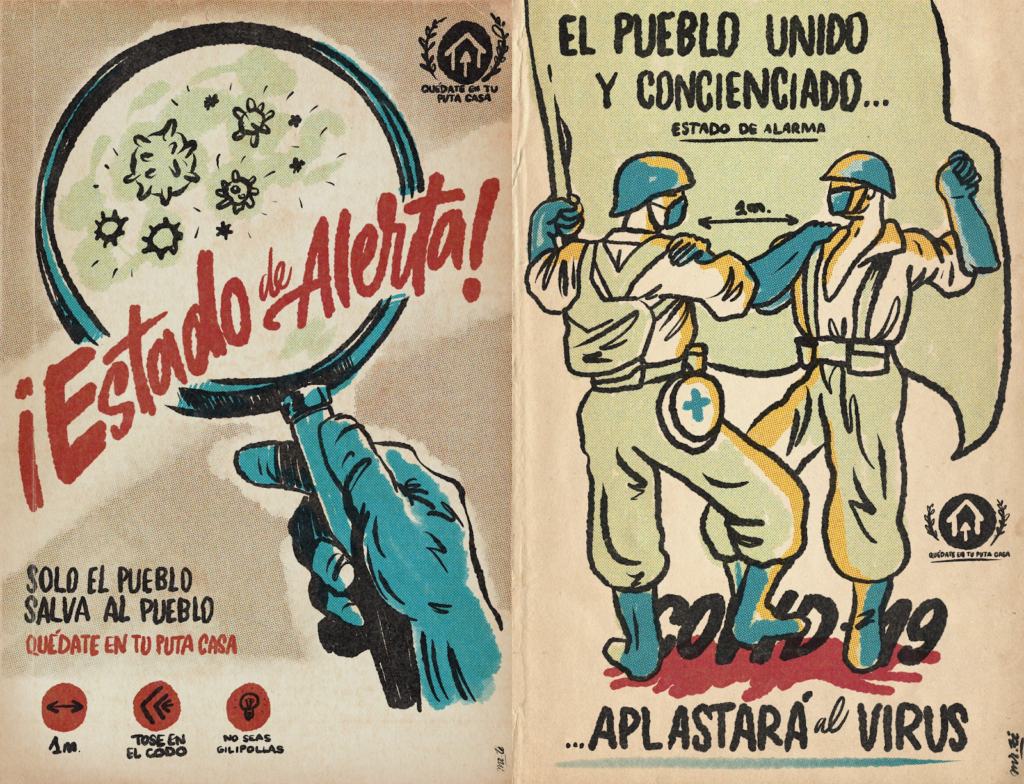

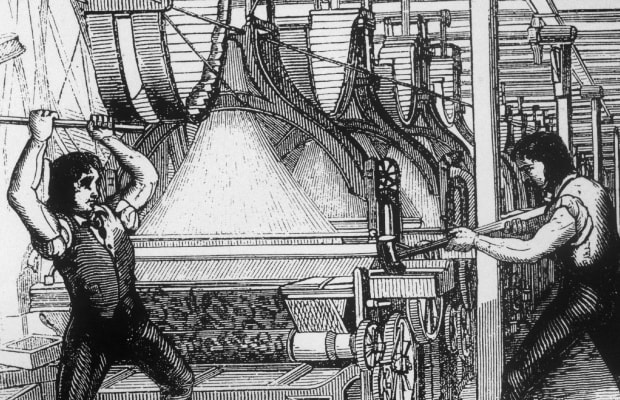

The Essenes were an ascetic sect that lived in highly organized communities in which they shared all property in common. Widely regarded as the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, they observed strict Jewish law and a monastic and withdrawn existence. However, this does not mean that they were politically neutral. They did not practice the kind of quietism often associated with asceticism, and instead played an active role in resistance to the Romans and took part in the revolution of AD 66. Though also strictly religious Jews, the zealots differed from the Essenes in that rather than taking part in a monastic lifestyle, they resembled a guerrilla movement dedicated to combatting the Romans and their aristocratic collaborators. They were also distinct in that they espoused a form of republicanism.

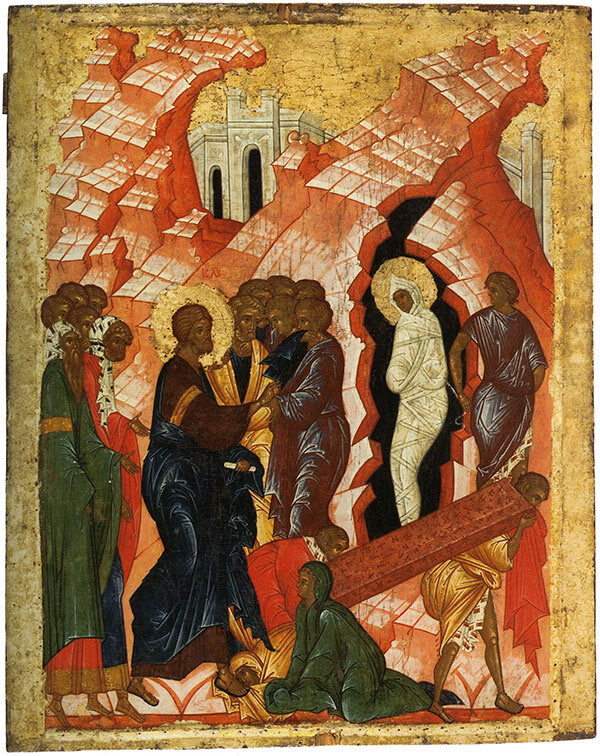

The Sicarii were a splinter group of zealots particularly feared by the Romans and Roman collaborators. They are often referred to as ‘dagger men’, as their preferred tactic in their resistance to Roman rule was to approach a Roman official or a collaborator in a crowded place, such as a market or festival, and quickly stab them before retreating into the crowd. The group that surrounded Jesus, the Nazoreans, was an apocalyptic revolutionary sect distinct from the zealots/Sicarii and the Essenes– they were not monastic like the Essenes, and they were not republican guerilla fighters like the zealots. But they were part of the same general political/religious movement, and as Conrad notes, “at least five of Jesus’s so-called twelve disciples were associated with, or came from, the ranks of the freedom fighters [zealots] and retained guerilla nicknames”.6

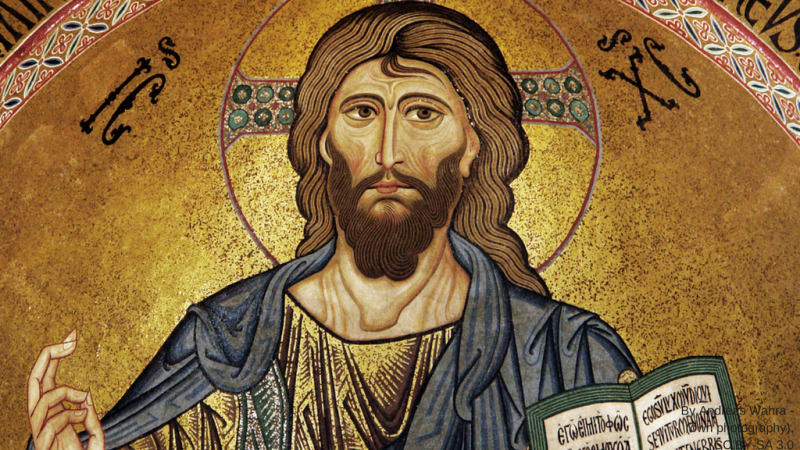

These religious sects were concerned first and foremost with the real world circumstances, which actually lent credence to the mysticism they surrounded themselves in. The mysticism of each group acted as a moral justification for its resistance to the much larger and more powerful forces of the Roman occupation. The Romans were more powerful, but they lacked moral righteousness, and the Jewish sects believed that their moral righteousness would eventually lead the Jewish lower classes to victory in spite of all odds. In this context it makes sense that so many of these sects took on a messianic aspect, in which a leader claims to be the predicted Jewish messiah. Jesus, for example, in addition to referring to himself as the messiah, considered himself and was considered by his followers as “king of the Jews,” a title which was then rewritten out of the New Testament as it was considered far too earthly and political. The New Testament writers/rewriters focus on the supposedly otherworldly titles of messiah and “christ,” although these too are tied inextricably to the political climate and the moral justification they gave to leaders of the revolutionary movement.7

Christianity, essentially a creation of Paul, was watered down to make itself more palatable to the Roman rulers. The Jesus movement, however, were not Christians but Jewish revolutionaries oppressed by the Romans. They followed strict Jewish law and customs, while a figure such as Paul promoted the violation of basic dietary laws and instructed converts to feel free to “eat any meat from the market” and enrich themselves in a way that was entirely contrary to the principles of the left-wing Jewish sects of the lower classes, from which the Jesus movement emerged. Completely antithetical to a Christian like Paul was the figure of James the Just, Jesus’s brother.

James’s existence is covered up and minimized throughout the New Testament for several reasons; that Jesus would have a biological brother grounded him in an earthly existence, and contradicted the cult of Mary as a perpetual virgin– “the more ethereal Jesus is made, the more James sticks out like a sore thumb”.8 But James was also suppressed because of his adherence to the class struggle ideology of the Nazoreans, promising retribution for the wealthy and the oppressors, leading early Christian theologians like Eusebius to question the authenticity of the only document evidencing James’s existence in the New Testament. The rhetoric of class struggle and retribution was alien to this third-century historian, as the image of Christ as the docile spiritual figure who recommended that his followers ”resist not evil” was already firmly entrenched in the Christian imagination.9

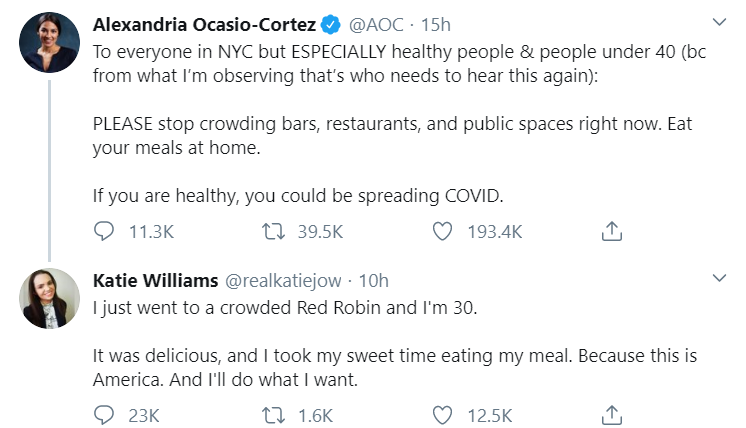

Like the Jewish revolutionary movement of the first century AD, the left today is splintered into countless factions, sects, and groups which at first glance stand little chance against the Empire or upper classes. Like them, while we might consider ourselves part of the same ‘broad movement’, many of us still insist on being part of separate organizations as a result of factional disputes, minute theoretical disagreements, and dedication to numerous little messiahs. Of course, not all lessons from the Jewish revolutionaries against Rome should be purely negative. We need the kind of moral passion and righteousness that guided these groups and which directly inspired the socialist party-movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A large part of the struggle to build a socialist mass party is building up that kind of strength, dedication, and confidence among the proletariat. The struggle for class leadership, however, is not one of a single messiah that will guide us out of the darkness and into the light, but of countless proletarian leaders who embody this messianic spirit. When the proletariat is aware of its collective power, no divine intervention is needed for us to win.

From the Book of James 5:1-7:

“Now listen, you rich people, weep and wail because of the misery that is coming on you. Your wealth has rotted, and moths have eaten your clothes. Your gold and silver are corroded. Their corrosion will testify against you and eat your flesh like fire. You have hoarded wealth in the last days. Look! The wages you failed to pay the workers who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty. You have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. You have fattened yourselves on the day of slaughter. You have condemned and murdered the innocent one, who was not opposing you. Be patient, then, brothers and sisters, until the Lord’s coming.”