Mikael Lyngaas argues that post-work theorists ranging from Bob Black to Srnicek and Williams are utopian socialism for the current era.

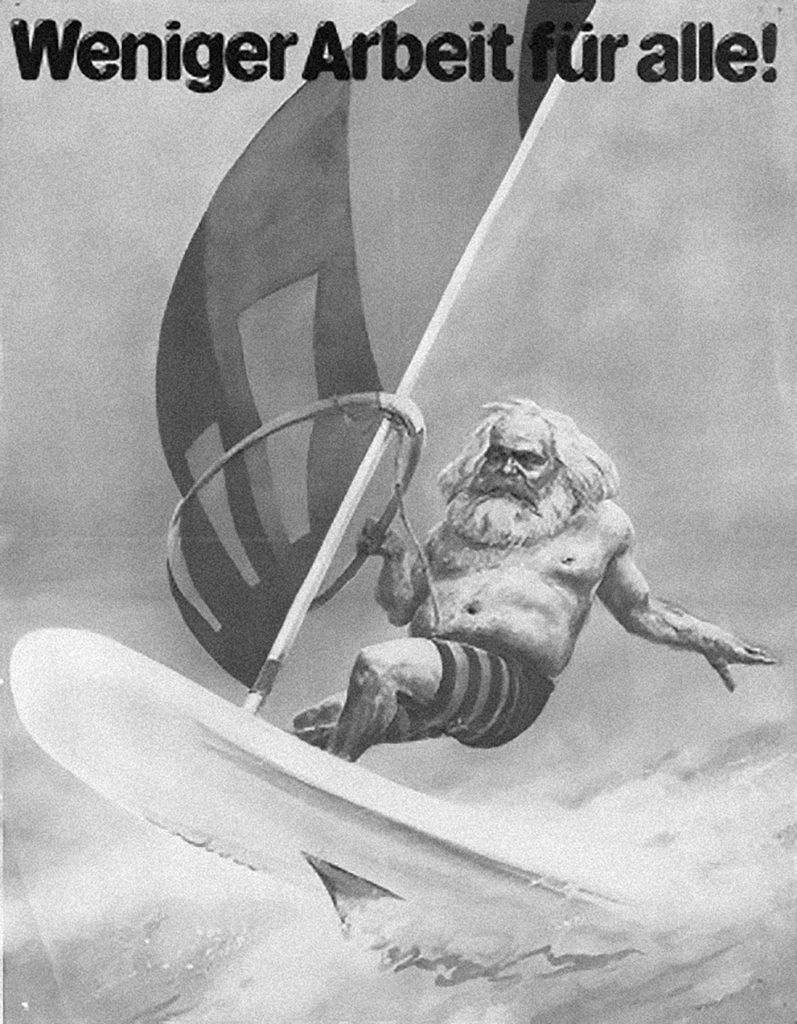

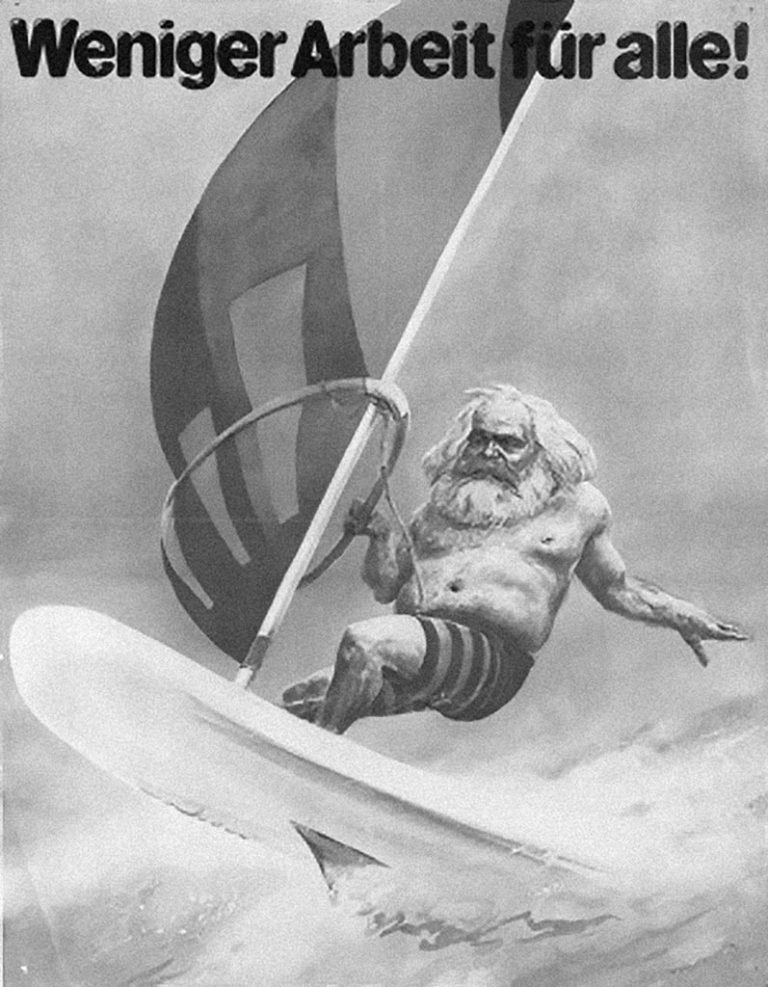

In 1845, Karl Marx wrote that in a communist society, workers would be freed from the monotony of a single draining job to “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner”. Since then, there have been many new ideas theorizing the nature of work and how capitalism exploits labor. These ideas have convinced a number of leftists to push for the emancipation of the working class through the abolition of work as a whole. This corner of the left argues that rising automation and movements for a universal basic income will eventually neutralize the contradictions of capitalism or abolish it altogether. “Post-work” theories, like other political groupings on the left, arise from the failures of the 19th-century socialist revolutions. Rather than a novel form of emancipatory politics, post-work is better understood as a return to the utopian socialist tradition of Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, and Henri de Saint-Simon, all of which Marx and Engels furiously polemicized against. Engels writes in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific that “One thing is common to all three [Owen, Fourier, and Saint-Simon]. Not one of them appears as a representative of the interests of that proletariat… Like the French philosophers, they do not claim to emancipate a particular class to begin with, but all humanity at once. Like them, they wish to bring in the kingdom of reason and eternal justice, but this kingdom, as they see it, is as far as Heaven from Earth, from that of the French philosophers”. A different, but similar kind of “kingdom of reason” is brought forward by contemporary post-work theoreticians. Instead of tackling the difficult questions of the transition from class society to a classless society and its revolutionary and strategic implications, the post-work theoreticians leap over these immensely difficult questions by favoring fantasies of technological futures free from labor and struggle. In this process, labor becomes something distorted from its material reality and takes on the form of the supposed core of capitalism, the root of class society, and all its evils.

The state of the modern left

To understand the origin and nature of the post-work debate we must start by studying recent history. The last hundred years have led to both major victories and defeats for leftist movements. From the Russian Revolution to the May 68 uprisings, there have been periods of both great confusion and great optimism among the working class. The fall of the Soviet Union and the sharp turn towards capitalism in China led many leftists and progressives into a culture of defeatism. If two of the biggest socialist nations in the world couldn’t unite and abolish capitalism, then is it even possible? Such pessimistic sentiments sometimes lead to nihilism, especially since there seemed to be nothing but short-term, minor victories in sight. The slogan “Socialism in our lifetime!” became a shadow of the past.

The turn toward reformism and class-compromise infected the European communist parties from May 68 onwards through the “Eurocommunist” trend of the 70s and 80s, which broke up many of these parties and disillusioned a generation of revolutionaries. As their membership numbers dwindled, huge swathes of working-class youth were left without proper representation and consequently strayed into the swamp of microsects and political isolation. There was a time when the left was more unified, and when theory and practice were more connected than today. Many of the so-called “New Left” movements of the 60s and 70s have steadily deemphasized Marxism, intending to overcome capitalism without falling prey to the authoritarianism of previous Stalinist projects. The antithesis to the Stalinist dogmas for these new leftists wasn’t a return to Marxism, but a return to philosophy and academia, as well as a retreat into emerging underground youth culture. The anarchist tendencies within many of these subcultures saw Marxism as an outdated and inherently authoritarian ideology.

Although defeatism is still present today, countless struggles continue all over the world, and the deadlock of defeat seems to be lifting. Still, there remains skepticism towards the “old” left strategies of class struggle through party and union organizing.

This is where the post-work theorists come in, by creating new radical alternatives to present political ideologies, including Marxism. Some post-work theories come from anarchist or left-communist traditions. These stem directly from the rejection of the “Leninist” party model (i.e. democratic centralism), and are most influential in the contemporary left as well as in academia. But if we’re going to ponder the question of abolishing work, we must start by looking into what constitutes work and why it is a debated term.

What is Work?

There are many types of work: Housework, creative work, wage labor, schoolwork, etc. But what do they all have in common? Work is best understood in terms of what Marx called labor-power, defined as “[the] mental and physical capabilities existing in a human being, which he exercises whenever he produces a use-value of any description”.12 Labor-power, although an unquantifiable abstraction, is central to humans and our nature. The concept of a use-value is the usefulness or utility of a given action or an object. Mental and physical capacity is, for Marx, what essentially separates humans from other animals and lays most of the foundation for historical development in general. The work performed, whether it be unskilled or skilled, emotional, or physical, is usually performed in return for an economic reward, such as the means of subsistence of oneself or others in tight-knit communities. In the early phases of human development, after reaching the needed labor for subsistence, excess work was shared and contributed to improving the community.

Work is essentially the most vital expression of human development, in which we realize our labor through the objectification of our surroundings. Under capitalism this process of realization is taken away from the producers in what Marx describes as a “loss of the object and bondage to it; appropriation as estrangement, as alienation”.3 The theory of alienation is vital to understanding both how modern work-relations operate and the need to form new modes of work void of alienation.

Through the given social forms within society, work became increasingly alienating as it separated humans from their work through brutal exploitation. From the expropriation of crops by feudal lords to capitalist exploitation through wage labor, the workers have been put into a division of labor, where human needs are constantly disregarded in the quest for cheaper labor and profits.4 In The German Ideology, Marx writes that “man’s own deed becomes an alien power opposed to him, which enslaves him instead of being controlled by him”.5 This lack of control doesn’t necessarily entail that all work is alienating to the core, but it is only a privileged few who can work off their creative projects or with small businesses, and ultimately they too must compete in the market. Capitalism ensures that even the best hobby becomes a mundane job.

For many, work can be both the object of great amounts of dignity and pride, as well as suffering and misery. The organized diminution of work might mean many things. Work-hours get longer to increase the surplus value produced by workers, not because there is a need within society for more of this or that product, but because of capitalisms’ need for constantly increasing profit. The solution to these problems for post-work theoreticians could be summed up by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams as the goal of a “world in which people are no longer bound by their jobs, but free to create their own lives”.6

The other part of this equation in need of address is leisure time. Leisure is often described as a period of time when we are recovering from work. There are, of course, a million ways to go about one’s leisure time— but that is beside the point. Under capitalism, leisure is capitalized on heavily as it is the time when we usually consume the most, whether it be television advertisements, food, or shopping. It’s the time when the wages paid to the worker are put back into the market, both out of the necessity of subsistence as well as heavily manipulated consumption for consumption’s sake.

There is also the psychological problem of leisure as breaking the “flow” of organized work. The choice to never work could lead to new forms of isolation and social pathologies.7 American anarchist and essayist Bob Black, taking influence from Fourier, writes in his 1985 essay The Abolition of Work that nonwork, or play, is favorable to work. This he argues by claiming that the arts, sciences, and political organization are more meaningful and fulfilling even though they stand outside modern work-life. Play, or the nonwork of life, is not passive leisure and should be understood as the “libidinization of life” as Black put it, or rather as a time to indulge in culture. An actor, painter, or musician does not necessarily produce a commodity for market purposes, but they perform labor and provide people with entertainment. Although contradictory, it may seem that “nonwork” is just work that is not waged labor. Black’s terms remain an undefined confusion, for how are we to separate “play” from “nonwork” and “wage labor”? And what kind of labor are we willing to allow? Artisanal, artistic, and culinary forms of labor are essential for all human societies, but the post-work theorists have the tendency to dismiss these in favor of philosophical jargon.

Black puts this argument of libidinization forward not as a political task of any group or mass of people but rather as the self-emancipation of the individual. Even Marx’s son in law, Paul Lafargue, wrote about the supposed cultured and virtuous importance of laziness and leisure in the 1883 essay The Right to be Lazy. This would go on to garner much disdain from workerists who stressed the importance of labor struggle for advancing socialism.8 We might find the starting point of post-work theories in Laufarague’s essay. The idealized notion of laziness and “non-work” might be seen as revolutionary in the face of precarious labor, long hours, and exploitation at every level of management and much of the work that is being done today is not only totally unnecessary but also detrimental to the wellbeing of the producers and the ecosystem globally. Yet at the same time, work is something inherently human which can bring about immense collective improvement as well as great personal fulfillment. It remains obvious that any revolutionary movement elevating laziness and vague jargon will eventually fizzle out into obscurity.

French communizer Gilles Dauvé also pointed out that work and its character under capitalism are so highly alienating and exploitative that it will impact every socialist attempt to change it. Dauvé describes it as “if social life revolves around this measure, whatever the mode of association, sooner or later the value will reappear”.9 Value for Dauvé is the process through which capital emerges, and must be stamped out completely if a communist revolution is to succeed. Yet the process of creating a new system away from capital however is, as Marx put it, “[born] with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges”.10 For Marx, the new society will emerge from a period of transition that is tainted by elements of the old mode of production. Dauvé points to the Soviet Union as an example of this approach to argue instead for the immediate abolition of work and value through the process of communization. Yet the failure of the Soviet Union was not inevitable due to a failure to immediately abolish work. The failures of the October Revolution to spread internationally meant the continuation of a state ‘socialism’ based entirely around bureaucratic party leadership. For the Soviet Union, work became intensified as it tried to out-compete the US in terms of military-might and productive output. Because of this, the political pragmatism of the Soviet politburo eliminated any notion of higher stages of communism or even world revolution as a whole. Although Dauvé’s criticism of the Soviet Union and similar states raises valid points they do not necessitate his solutions.

How do we end work?

For Italian anarchist Alfredo M. Bonanno the problem at hand was the transformation of wage labor from “obligatory doing into free action”, similar to Black.11 This, of course, presupposes that a post-scarcity economy is already achieved and that society is moving further towards a higher stage of communism. Bonanno emphasizes the importance of creativity in order to “destroy work”, and, like other writers on the topic, criticizes the notion of non-activity. Like Black, Bonanno offers vague statements to avoid the implications that the destruction of work might have.

Unlike Black and the other utopians, Bonanno and Dauvé both represent (in different ways) a more uncompromising and insurrectionary utopianism. Bonanno emphasizes the revolutionary nature of “destroying work”, as a sort of self-realization without wage labor leading to collective experimentation, which in turn ends capitalism.12 Here lies a strain of individualism that rejects party organization and political strategy in favor of individual expressions and creativity in direct action. The focus on direct action and insurrection is also found in the works of Dauvé who, like the anarchists, rejects a transitional period to communism in favor of the total abolition of the value-form. This means the total abolition of any economic framework for a transitional period as a whole, leaving an enormous gap in the transition over from capitalism to communism. This world revolution is set forward more like a biblical reckoning rather than a long-term political goal carried forward by a mass proletarian movement.13 The theoretical difference here is that Dauvé does not abandon Marxism or the history of communism, though he draws on anarchists and the autonomists of the 60s and 70s for inspiration. Although Dauvé offers a valuable critique of bureaucratization and top-down leadership, his theory of communization remains an obscure tendency with its lack of a proper political and economic strategy. This again is sacrificing a viable strategy for non-flexible principles.

It is obvious that the struggle for socialism has to be fought out openly by the broad masses against the bourgeoisie, and that this has historically been effectively done through the proletarian party. The resistance faced by revolutionaries shows clearly that socialism can not be established in a blink of an eye but rather through the organized fight against bourgeois reaction.

Universal Basic Income

Another approach that has been popularized in later years is the universal basic income (UBI) which emerged as a somewhat broad public policy in the 70s before vanishing. It was popular among both liberals and conservatives as a way to replace public services. But the rise of neoliberalism secured the position of the ruling class and allowed enormous cuts in social welfare, rendering the liberal UBI useless. For Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, the UBI is, among other demands, a part of what they call, ironically enough, “non-reformist reforms”. These are obviously just reforms. Although these reforms are intended to abolish capitalism, they often look more like steps towards an uncertain technocratic utopia. Instead of understanding UBI as an obscure neoliberal project long since cast aside, Srnicek and Williams reproduce a “progressive” approach to what is inherently neoliberalism. Their emphasis on think tanks as a means to put forward their theories also echoes the logic of the bourgeoisie, who seek to externalize political on-the-ground activity as much as possible to keep it out of mind. Srnicek and Williams do not look to the socialist tradition or the labor movement for inspiration and instead gaze at the ivory tower.

Immediate goals are traditionally theorized as tools for raising class-consciousness which will then lead to a mass revolutionary movement, but Srnicek and William instead aim at long-term technocratic reforms. Through technology and extensive labor struggles for shorter work weeks, full automation, and a universal basic income, Srnicek and Williams argue that we can achieve a post-work society. They envision this as a stage of capitalism, or a process of transformation away from capitalism in which the reserve labor army is abolished and work becomes voluntary, creating a society where labor makes the rules and capital obey.14 In this scenario class-consciousness would surely arise from the immense struggle against capital, and the new social relations formed with the abolishment of unemployment and poverty. This is supposed to lay some of the groundwork for a communist society where work is flexible, and few people are tied to one profession or company their entire life.15 Neoliberalism and its hegemony would slowly be undermined, not only by the masses of workers receiving a UBI but also through academia creating new approaches to problems of socialist calculation.

Srnicek and William’s theoretical proposals for socialism break with more traditional Marxist ideas of revolution. What they get right is that an emphasis on “utopianism” and long-term goals is necessary to counteract the global left’s defeatism and nihilism in the face of the old questions of emancipation. If everything always remains in the scope of 5, 10 years, or as long as a lifetime, very few emancipatory projects seem worthwhile. Yet a post-work society achieved through automation and UBI would face a myriad of difficult political tasks that are immediate. For Srnicek and Williams, many of these core demands can only be looked at as prefigurative politics aiming at slowly changing social relations for the better.16 Even in a society with a UBI and full automation the contradictions between the interests of capital and the interests of labor will come to a breaking point because the capitalist class cannot allow an ever-expanding UBI as profits decline. To even reach this point would be a long, arduous, and massive political task which makes it a vital necessity for post-work theories to create applicable radical politics. After all, Srnicek and Williams fail to even consider the end of alienating work by transforming the nature of work itsef. UBI becomes not a means to an end but an end in and of itself.

What then, is Srnicek and William’s strategy for such a political project? Their strategy is what they call an “ecology of organizations”— a myriad of left groupings such as trade unions, interest groups, parties etc. A good example of this would probably be the recent Yellow vest movement or Occupy which consisted of many different groups but held no central leadership or demands.There is little description on how these collections of organizations might function without any form of non-spontaneous centralization.17 Creating hegemony and insisting on influencing cultural and political spaces usually leads to what Srnicek and Williams call “folk politics”, that is, the politics of loose and spontaneous groupings with few consistent aims such as the Occupy movement.18 Srnicek and Williams heavily critique folk politics but, ironically, their project also falls prey to utopian folk politics by relying on spontaneity and unity between vastly different, often hostile groups for establishing a hegemony. This theory echoes Dauvé by being an obvious response to state socialism and subsequent reliance on spontaneous struggle. For Dauvé, this struggle is revolutionary, but not for Srnicek and Williams. For them, it might not even be emancipatory at all, admitting that a post-work society may entail colonialism, racism, and patriarchy if it is not global. A future beyond neoliberal wage labor may therefore not only be co-opted by capital, but also be used to further imperialistic expansion.19

For example, automation may also work to the disadvantage of workers as more and more people are placed into the reserve army of labor. In response to this, many have pointed to the possibility that new technology will create demand for new skilled workers. Yet, as pointed out by Lukas Schlogl and Andy Sumner, automation remains a problem for the low-skilled workers in periphery states.20 This shines a light on the fact that the project of automation and UBI, when isolated to a single country, could easily be co-opted by liberals, conservatives, and fascists alike. Absent an internationalist perspective, the ideas of post-work theory can morph into variants concerned not with how to bring about socialism or a more egalitarian society, but rather how to push capitalism into complete self-destruction. This is the politics of accelerationism, a theory which presupposes an intensification of capitalism to bring about a new horizon of possibilities through rapid technological invention. This theory, inspired by Deleuze & Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, is plastered across many popular leftist works, such as Paul Mason’s Postcapitalism. It has also been combined with neo-Nazi race theory and reactionary ideology by figures such as Nick Land who seek to accelerate the demise of the globalized world order into a “patchwork” of “techno-feudalist” city-states. However, since the early 00s, accelerationism has fallen out of favor everywhere except small corners leftwing academia, becoming more of a bizarre internet subculture. Just like in the late 30s when many believed they were witnessing the death of capitalism, we cannot wait for capitalism to defeat itself. This would be equivalent to, in the words of Rosa Luxemburg, waiting “until the sun burns out”. Instead, the working-class needs to consciously organize itself for its own emancipation with a clear goal of communism, not by vague prospects of a new technological paradigm.

Another approach to the topic of UBI and post-work society can be found in the work of Feminist Theoretician Kathi Weeks, whose book The Problem with Work stresses the principled demand for the wages of domestic workers as a means to obtain a UBI.21 Weeks argues that the utopianism in post-work imaginaries cuts through the traditional dichotomy between reform and revolution. This is done by re-thinking the transformation away from capitalism as a struggle that is won on a day-to-day basis through strikes, protests, and electoral victories to produce “new forms of relations”.22 Vagueness aside, does this approach really break with the dichotomy of reform or revolution? Reformism entails a firm stance against revolutionary action but the revolutionary position supports fighting immediate reformist demands, including many championed by Weeks, Srnicek, and Williams, in addition to the goal of seizing power and abolishing capitalism. Theoretically, the emphasis on creating something new seems to outweigh the project of actually creating coherent politics. The rejection of classical Marxism without a coherent alternative means that post-work theories are stuck within various political science and philosophy departments, instead of being a force in fighting capitalism. Utopian socialism has changed a lot since the 18th century, but it remains stuck in visions of the future without making so much as a single step into that future. The long-term strategy of organization, agitation, and education forces us to deal with the material conditions of the proletariat as well as the current political situation. Envisioning the future and theorizing other social relations can very well be a means of drawing people into the socialist left, but as we’ve explored, they offer very little in terms of actual strategy. If we are to take socialism seriously, we must critique this trend wherever it occurs.

Conclusion

The struggle for domestic workers’ right to wages, a global UBI, and full automation are all important topics for any contemporary radical looking to end the alienation of labor. Envisioning a possible future and what it might look like is important for creating the possibility for socialism. The imagination of post-work may inspire class struggle but it is also useless without a well-thought-out and systematic approach to enact their demands. The common lack of a clear political strategy and semantic games about the correct meaning of the word “work” place most post-work theories into the camp of pseudo-academic phrase-mongers rather than serious revolutionaries. Slogans such as “End all work!” might seem appealing, but if we take it together with the most common definitions of labor it would quickly lead down the rabbit hole of meaninglessness and despair. There is already a myriad of working-class demands that are worth fighting for without having to delve into the jargon-filled language of academic philosophers. As capitalism creates work that is mundane and meaningless, the post-work theoreticians respond by trying to regain some notion of working-class agency. Yet this agency is mistaken and only exists in theory.

Technology might bring an end to neoliberalism, or even capitalism, but only under the control of the producers through intensive struggle. It is not the task of serious Marxists to create prophecies about the future but rather to deal with the current situation as well as the vast history of communism and the working class. There will be no grand acceleration of capitalism, but rather a continuing economic decline together with an enormous environmental collapse. Post-work theories are then revealed to rely heavily on predictions and technological optimism for the future without dealing with the present or the past. Marx says in the Eighteenth Brumaire that “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past”. Without properly connecting theory to history and political practice it might never break out of the sphere of philosophy and speculation. We already have over a hundred years of working-class struggle to learn from and thousands of pages of valuable theory that directly corresponds with the lived reality of the masses. Although we should not fetishize the past, we should avoid doing the same to the possible future.

There is naturally a great need to go beyond wage labor and abolish it with more socialized forms of labor aimed at bettering the quality of life for all. This emancipatory project can however simply not be reduced down to a revolutionary imagination or vague hyperbolic demands. The notion of new theory for a new time might be appealing but we do not need to reinvent the wheel. We need to take up the study of Marxism and fight for the immediate goals of the working class as well as the long-term goal of communism. Post-work doesn’t help us do this, they simply create new vocabularies that lead down avenues of vagueness and confusion.