Translation and introduction by Rida Vaquas. Original article can be found here.

Introduction

It has long become a truism that Marxism failed to grasp the problem of nationalism, particularly as the second half of the twentieth century saw national revolutions flourish whilst socialist movements collapsed. As national identity cements itself as a political force in our times, the Communist Manifesto’s declaration that “national one-sidedness and narrowmindedness become more and more impossible” can strike some as impossibly glib. The globalization of capital, far from diminishing the prospects of the nation-state, has instead spawned many nationalisms and even shaken the stability of ‘settled’ nation-states. Both Britain and Spain have faced secessionist movements in recent years. In the wake of this theoretical “failure” of Marxism, the response of Marxists has too frequently been to pack up and go home, taking the failure for granted. Nowadays the claim of “the right of nations to self-determination” is the accepted solution to the national question, even when no plausible working out has been shown. The “Leninist position” has become reified as part of socialist political programmes in the 21st century, even as very little sets it apart from the principle of national self-determination advocated by the Democratic President Woodrow Wilson.

After over half of a century of socialists firmly embracing nation-states, perhaps it is time to re-evaluate this “failure”. As opposed to understanding the principle of national self-determination as necessary to fill a hole in Marxist theory, we should understand it as blasting the hole itself and calling for the bourgeoisie to fill it. It is time to shed a light on the debates that took place within socialism before the principle of national self-determination became widely accepted as a necessary part of socialist programmes, in the period of the Second Socialist International between 1890 and 1914. This means an analysis of the national question from peripheral socialist parties rather than the centers in Germany and Russia. To seriously appraise the defeated alternatives to national self-determination allows us to appreciate that the nation-state is not the final word in history.

Much of the historiographical understanding of the national question debate in this period frames it as a dispute between two of the leading personalities: Rosa Luxemburg and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Rosa Luxemburg, as co-founder of the Social Democratic Party of Poland and the Kingdom of Lithuania (henceforth SDKPiL), positioned her party against the social patriotism of the rival Polish Socialist Party (henceforth PPS) who demanded the restoration of Poland, which was then partitioned under Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. She fought against the Polish claim to independence at the London Congress of the Second International in 1896 and consistently argued for the Polish socialists in Prussia to be integrated into the German Social Democratic Party (henceforth SPD), rather than being a separate party. On the other hand, Vladimir Lenin, writing from the heart of the Tsarist empire, understood the right of nations to self-determination as a “special urgency” in a land where “subject peoples” were on the peripheries of Great Russia and experienced higher amounts of national oppression than they did in Europe.1

Rosa Luxemburg’s position has been recently evaluated as effectively forming a bloc with the chauvinist bureaucracy of the SPD.2 Luxemburg has further been accused of underestimating the force of national oppression and hence of “international proletariat fundamentalism”.3 By examining the debate as it took place in the Second International as a whole, we can understand these assessments of the case against national self-determination to be unsatisfactory and re-appraise the positive legacy of revolutionary internationalism.

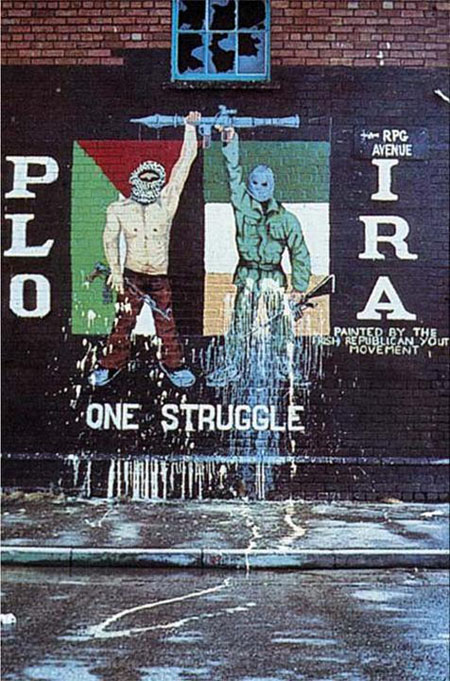

Meanwhile, Lenin’s position has received praise in the wake of socialists relating to the national liberation movements of the 20th century, as “championing the rights of oppressed nations”.4 In this framework, the “liberation” of oppressed nations is the precondition of international working class unity and therefore national struggle clears the way for class struggle.

However, it is important to interrogate the consistency of Lenin’s position and hence dismantle the idea of a coherent Leninist position which emerges from its conclusions. The right of nations to self-determination, as Lenin took care to emphasize, could not be equated with support for secessionist movements. In 1903, as the Russian Social Democratic Party adopted the national self-determination as part of its programme, Lenin argued that “it is only in isolated and exceptional cases that we can advance and actively support demands conducive to the establishment of a new class state” against the calls of the PPS for the restoration of Poland.5 This lack of sympathy to struggles for national independence in practice was noted by contemporary socialist supporters of nationalism, the Ukrainian socialist Yurkevych polemicized that Lenin supported the right of national self-determination “for appearances’ sake” whilst in actuality being a “fervent defender of her [Russia’s] unity”.6 If the exercise of the right of national self-determination naturally leads to the formation of an independent state, Lenin was politically opposed to it in many of the same cases as Luxemburg. This distinction may be lost upon later “Leninists”, such as the Scottish Socialist Party who assume Scottish independence to be an extension of national self-determination, but it should not be obscured from our view.

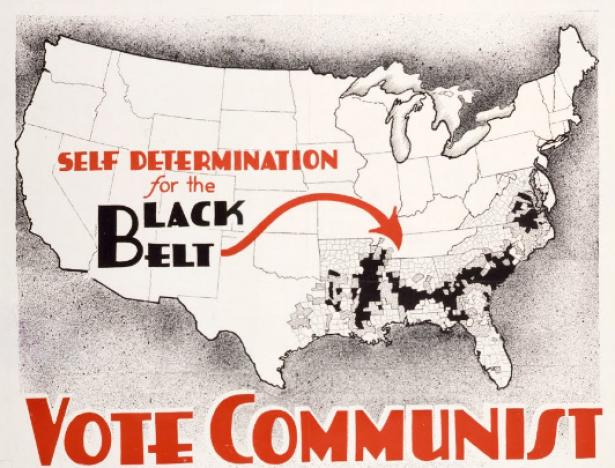

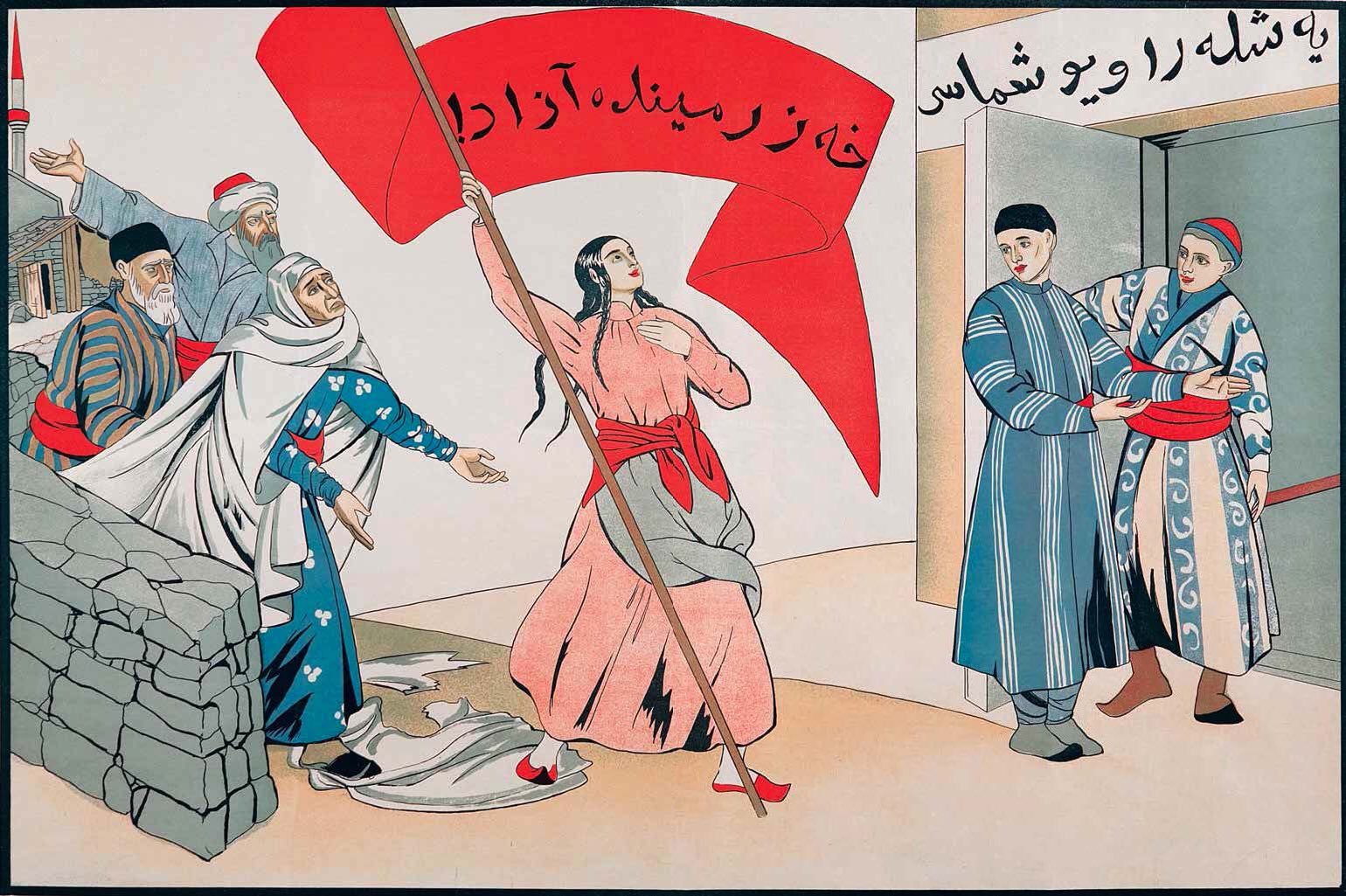

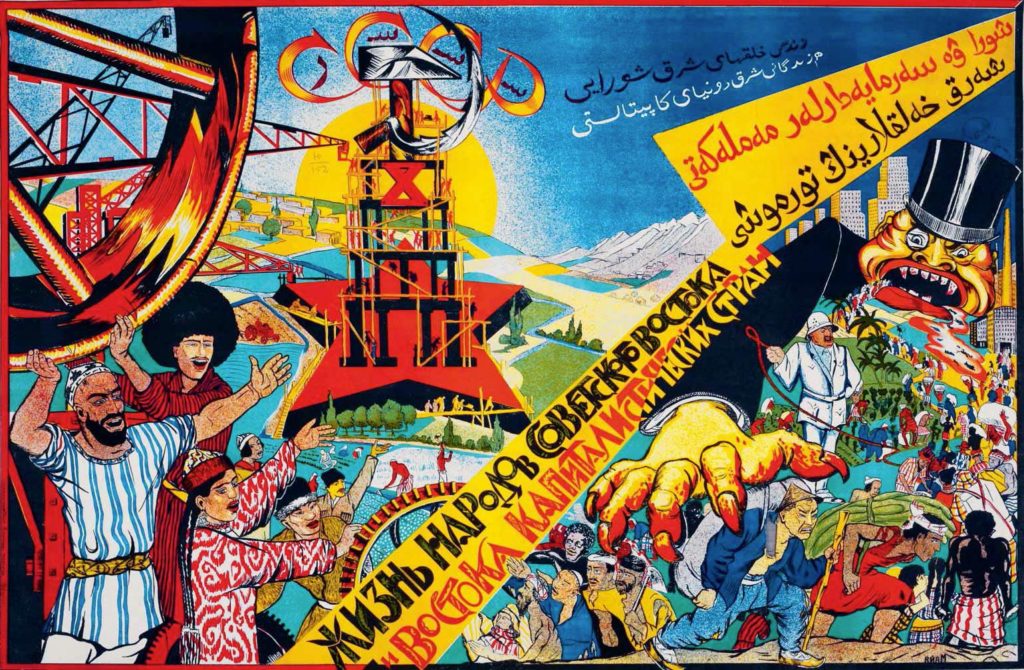

Moreover, Lenin’s position changed through the course of his political experiences. The early Soviet government’s policy on nationalities required that “we must maintain and strengthen the union of socialist republics”.7 Instead of promoting secession, the Bolsheviks pursued a policy of Korenizatsiya (nativization) in which national minorities were promoted in their local bureaucracies and administrative institutions spoke the minority language. Hence national autonomy within a larger state was seen as an adequate guarantor of national rights to oppressed nations. Far from a consistent “Leninist position” of supporting the exercise of the right of national self-determination in nearly all cases, it is raised, what emerges as Lenin’s actual position is a theoretical “right” whose use is very rarely legitimated by historical conditions and the interests of the working class in practice, even where there are popular nationalist movements. Is this “right” really so far from the metaphysical formula that Rosa Luxemburg derided the principle of self-determination as?

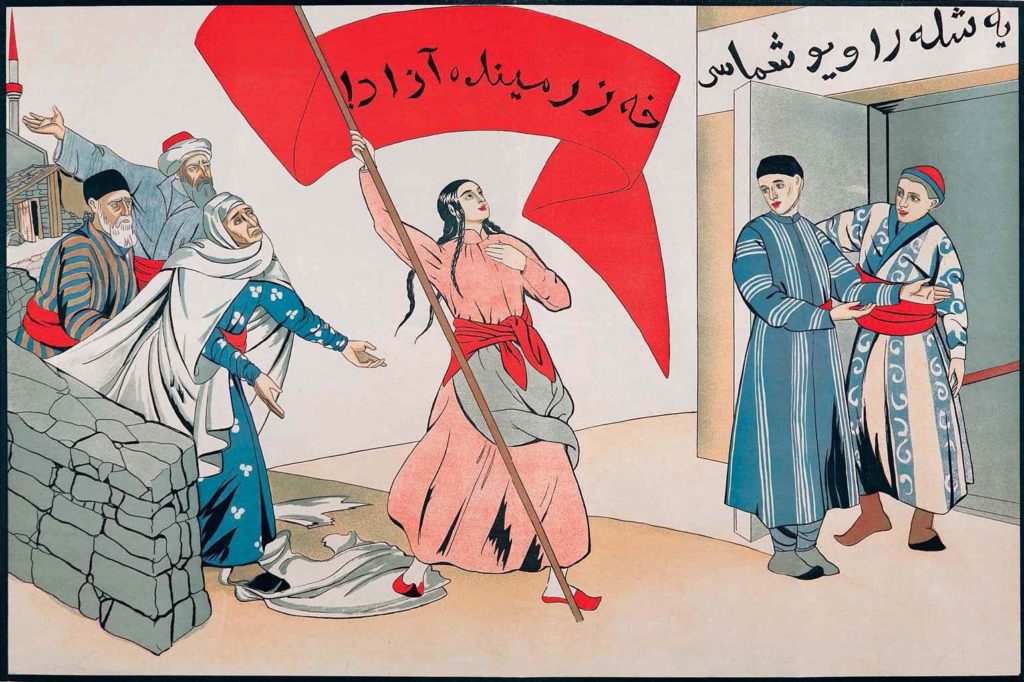

Having dealt with the historical misapprehensions of Lenin’s position, it is time to reappraise the perspective of Rosa Luxemburg. Whilst her position is frequently presented as a theoretical innovation on her part, Luxemburg herself noted a longer anti-national heritage. Assessing the legacy of the earlier conspiratorial Polish socialist party, the Proletariat, she argued that they “fought nationalism by all available means and invariably regarded national aspirations as something which can only distract the working class from their own goals”.8 Far from national self-determination being an accepted orthodox Marxist position, we should keep in mind that the PPS had to argue for it at multiple congresses of the Second International in the case of Poland. After the revolutionary upsurges in Russia in 1905, a considerable segment of the PPS formed the PPS-Left, which similarly disavowed national independence as an immediate goal for socialists.

There were three core strands to Luxemburg’s opposition to national self-determination. Firstly, it was materially unviable given that no new nation could achieve economic independence owing to the spread of capitalism. Secondly, pursuing national self-determination in the form of supporting independence struggles did not make strategic sense for socialists as it inhibited them from placing political demands upon existing states. Finally, and most saliently for socialists today, even if national self-determination was politically and economically more than a utopian pipe-dream, it would still be against the interests of the working class to pursue it.

These latter two strands are more decisive in understanding Rosa Luxemburg’s position and are what make it more than a miscalculation rooted in economic determinism. Luxemburg herself appreciated the separation of the “economic” from the “political” under capitalism, as she argued capitalism “annihilated Polish national independence but at the same time created modern Polish national culture”.9 Far from being a national nihilist, Luxemburg stated that the proletariat “must fight for the defense of national identity as a cultural legacy, that has its own right to exist and flourish”.10 The 20th century has proven that political independence is materially possible. It has not shown that it is a remedy for national oppression and that it is a worthy goal for socialists.

National self-determination, in Luxemburg’s words, “gives no practical guidelines for the day to day politics of the proletariat, nor any practical solution of nationality problems”.11 As we can observe from Lenin’s policies on nationalities, there is no consistent conclusion that comes from the acknowledgment of this “right”. The only real conclusion is that affairs must be settled by the relevant nationality, which is presented as a homogeneous socio-political entity, as opposed to a site of class struggle in itself. The impracticality of this formula was not only resisted by Luxemburg, but also by Fritz Rozins, a Latvian socialist. Rozins, criticizing the position of Lenin in 1902, made the argument that several nations can occupy the same territory which problematized the demand for national self-determination.12

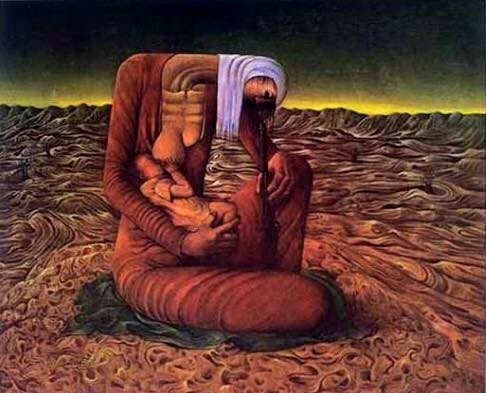

When examining contemporary manifestations of the national problem, these issues are thrown into sharper focus. In the case of Israel and Palestine, the framework of two competing claims of national self-determination which need to be reconciled with each other ultimately leads to endorsing an indefinite political and economic subordination of one nation by another. One way some sections of the modern Left attempt to address this is by rendering one nation’s claim (Israel’s) as inherently illegitimate, on account of its annexationist political project and racist domestic policy, and hence dismissing Hebrew Jewish people as constituting a national people with particular rights. However, making the right of national self-determination contingent upon the political project of its claimants would leave very few nations, if any, with this “right” at all, as its claimants tend to be an aspirational national bourgeoisie, whose class interests are tied to the continuation of the subjugation of the working class peoples within a territory, including working-class national minorities. The best way forward is to abandon such a “right” altogether, which assumes a basic unity between the interests of the oppressor and oppressed as part of the same nation. The question should instead be examined from the perspective of the common interests of the Israeli and Palestinian working classes against the Israeli state.

Abandoning national self-determination as a democratic “right”, which socialists should cease to guarantee as a part of their programmes is often equated with opposing national struggles in all cases. Rosa Luxemburg’s attitude to Armenia at the beginning of the 20th century demonstrates this is not the case. Unlike a number of her contemporaries who were concerned that the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would only strengthen the hand of Tsarist Russia, Luxemburg argued emphatically that “the aspirations to freedom can here make themselves felt only in a national struggle” and hence that Social Democracy must “stand for the insurgents”.13 In her reasoning, the national struggle was appropriate for Armenia in a way that it was not for Poland, as the Armenian territories lacked a working-class, and were not bound to the Ottoman Empire by capitalist economic development, but by brute force. Perhaps ironically, this put her at odds with the Armenian Social Democrat David Ananoun, who rejected national secession on the grounds that new nation-states could not guarantee the rights of national minorities within them. The Armenian Social Democrats “always subordinated the solution of the national problem to the victory of the proletarian revolution”, including rejecting the specificity of Armenian situation.14 One could say they surpassed the supposed “international proletariat fundamentalism” of Rosa Luxemburg.

Both Ananoun and Luxemburg rejected territorial national self-determination as a framework, yet drew different conclusions in the specific case of Armenia. Why is that? By moving away from the idea that national oppression can be resolved by emergent nations, settling national oppression becomes the affair of the working class. Franz Mehring, on the left-wing of the SPD, clarified this in the case of Poland: “The age when a bourgeois revolution could create a free Poland is over, today the rebirth of Poland is only possible through a social revolution in which the modern proletariat breaks its chains”.15 Supporting a nationalist movement for Luxemburg only became tenable in the absence of an organized working class, and nationalism could not be the slogan raised to lead it. For Ananoun, conscious of the lack of capacity of forming coherent territorial states along ethnic lines in heterogeneous Transcaucasia, his position was conditioned by the concern of maintaining the rights and cultures of national minorities in territories that were necessarily going to contain multiple nationalities. This reveals the national question as it should be for the socialist movement: a question of the interests and the capacities of the working classes to place their demands upon bourgeois class states, and hence, the conquest of political power by the working classes. The maintenance of nationalities, in the form of culture and language, is part of the political and social rights that the working class wins through struggle against class states, not by creating them. Rather than debating whether a nation ought to exercise a “right” of self-determination, socialists should see the nation itself as a veil, under which contending classes are hidden.

What fundamentally determined Rosa Luxemburg’s attitude was understanding that nationalism was not an empty vessel in which socialists could pour in proletarian content. The ideology of nationhood intrinsically demands temporary class collaboration, at the very least, to the advantage of the ruling classes. An article she penned in January 1918, intended as friendly criticism of the early Soviet government’s policy on nationalities, most clearly articulates this perspective:

“The “right of nations to self-determination” is a hollow phrase which in practice always delivers the masses of people to the ruling classes.

Of course, it is the task of the revolutionary proletariat to implement the most expansive political democracy and equality of nationalities, but it is the least of our concerns to delight the world with freshly baked national class states. Only the bourgeoisie in every nation is interested in the apparatus of state independence, which has nothing to do with democracy. After all, state independence itself is a dazzling thing which is often used to cover up the slaughter of people.”16

This has been vindicated by historical experience. When we look at Poland today, a right-wing government is installing “Independence Benches” that play nationalist speeches.17 The speeches were delivered by none other than Józef Piłsudski, a former leader of the PPS who later abandoned socialism altogether. The warning of the Polish Communist Party, published in 1919, a year after Polish independence, that bourgeois “independence” in reality meant “the brutal dictatorship of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat” has proven more correct than any fantasy about the achievement of independence offering a permanent resolution to the national question, opening up the battlefield of class struggle.18 The formation of new class states does not resolve national oppression, so much as redistribute it.

Revolutionary internationalism, or the so-called “international proletariat fundamentalism”, stands as a rejoinder to those who seek shortcuts to social revolution by the construction of nation-states. Yet it also allows for a more positive assessment of nationalities. Rather than being bound to the political form of territorial states responsible for the oppression of millions across centuries, the traditions, institutions, and languages associated with nationalities can become part of a universal cultural legacy and human inheritance that requires neither the violence of borders nor of class rule. We can be moved by the words of the poet Adam Mickiewicz without scrambling to statehood. Capitalist development has made the endgame of the exercise of national self-determination, the nation-state, a dead-end for socialists. It is now necessary to pose the national question once more and seek different answers.

Fragment on War, National Questions and Revolution

When hatred of the proletariat and the imminent social revolution is absolutely decisive for the bourgeoisie in all their deeds and activities, in their peace programme and in their policies for the future: what is the international proletariat doing? Completely blind to the lessons of the Russian Revolution, forgetting the ABCs of socialism, it pursues the same peace programme as the bourgeoisie, it elevates it to its own programme! Hail Wilson and the League of Nations! Hail national self-determination and disarmament! This is now the banner that suddenly socialists of all countries are uniting under – together with the imperialist governments of the Entente, with the most reactionary parties, the government socialist boot-lickers, the ‘true in principle’ oppositional swamp socialists, bourgeois pacifists, petty-bourgeois utopians, nationalist upstart states, bankrupt German imperialists, the Pope, the Finnish executioners of the revolutionary proletariat, the Ukrainian sugar babies of German militarism.

In Poland the Daszyńskis are in a cosy union with the Galician slaughterers and Warsaw’s big bourgeoisie, in German Austria, Adler, Renner, Otto Bauer, and Julius Deutsch are arm-in-arm with the Christian Socials, the landowners and the German Nationals, in Bohemia the Soukup and the Nemec are in a close phalanx with all the bourgeois parties – a touching reconciliation of the classes. And everywhere the national drunkenness: the international banner of peace! The socialists are pulling the bourgeoisie’s chestnuts out of the fire. They are helping, using their ideology and their authority, to cover up the moral bankruptcy of bourgeois society and to save it. They are helping to renovate and consolidate bourgeois class rule.

And the first practical coronation of this unctuous policy – the defeat of the Russian Revolution and the partition of Russia.

It is the politics of 4th August 1914, only turned upside down in the concave mirror of peace. The capitulation of class struggle, the coalition with each national bourgeoisie for the reciprocal wartime slaughter transformed into an international world coalition for a ‘negotiated peace’. The cheapest, the corniest old wives’ tale, a movie melodrama – that’s what they’re falling for: Capital suddenly vanished, class oppositions null and void. Disarmament, peace, democracy, and harmony of nations. Power bows before justice, the weak straighten their backs up. Krupp instead of cannons will produce Christmas lights, the American city Gari [?] will be turned into a Fröbel kindergarten. Noah’s Ark, where the lamb grazes peacefully next to the wolf, the tiger purrs and blinks like a big house cat, while the antelope crawls with horns tucked behind the ear, the lions and goats play with blind cows. And all that with the help of the magic formula of Wilson, of the president of the American billionaires, all that with the help of Clemenceau, Lloyd George and the Prince Max of Baden! Disarmament, after England and America are two new military powers! Disarmament, after the technology has immeasurably advanced. After all, states sit in the pocket of arms and finance capital through national debt! After colonies – colonies remain. The ideas of class struggle formally capitulate to national ideas here. The harmony of classes in every nation appears as the condition for and expansion of the harmony of nations that should emerge out of the world war in a ‘League of Nations’.

Nationalism is an instant trump card. From all sides, nations and nationettes stake out a claim for their right to state formation. Rotted corpses rise out of hundred-year-old graves, filled with fresh spring shoots, and “historyless” peoples, who never formed an independent state entity up until now, feel a violent urge towards state formation. Poland, Ukraine, Belarussians, Lithuanians, Czechs, Yugoslavia, ten new nations of the Caucasus. Zionists are already erecting their Palestine Ghetto, provisionally in Philadelphia. It’s Walpurgis Night at Blockula today!

Broom and pitch-fork, goat and prong… To-night who flies not, never flies.

But nationalism is only a formula. The core, the historical content that is planted in it, is as manifold and rich in connections as the formula of ‘national self-determination’, under which it is veiled, is hollow and sparse.

As in every great revolutionary period the most varied range of old and new scores come to be settled, oppositions are brought to their conclusions: antiquated remnants of the past, the most pressing issues of the present and the barely born problems of the future whirl together. The collapse of Austria and Turkey is the final liquidation of the feudal Middle Ages, an addendum to the work of Napoleon. In this context, however, Germany’s breakdown and diminution is the bankruptcy of the most recent and newest imperialism and its plans for world mastery, first formed in war. It is equally only the bankruptcy of a specific method of imperialist rule: by East Elbian reaction and military dictatorship, by siege and extermination methods, first used against the Hereros in the Kalahari Desert, now carried over to Europe. The disintegration of Russia, outwardly and in its formal results: the formation of small nation-states, analogous to the collapse of Austria and Turkey, poses the opposite problem: on the one hand, capitulation of proletarian politics on a national scale before imperialism, and on the other capitalist counterrevolution against the proletarian seizure of power.

A K. [Kautsky] sees in this, in his pedantic, school-masterly schematism, the triumph of ‘democracy’, whose component parts and manifestation form are simply the nation-state. The washed-out petty-bourgeois formalist naturally forget to look into the inner historical core, forgets, as an appointed temple guard of historical materialism, that the ‘nation-state’ and ‘nationalism’ are empty pods into which each historical epoch and set of class relations pour their particular material content. German and Italian ‘nation-states’ in the 1870s were the slogan and the programme of the bourgeois state, of bourgeois class rule. Its leadership was directed against medieval, feudal past, the patriarchal, bureaucratic state and the fragmentation of economic life. In Poland the ‘nation-state’ was the traditional slogan of agrarian-noble and petty-bourgeois opposition to modern capitalist development. It was a slogan whose leadership was directed against the modern phenomena of life: both bourgeois liberalism and its antipode, the socialist workers movement. In the Balkans, in Bulgaria, Serbia and Romania, nationalism, the powerful outbreak of which was displayed in the two bloody Balkan wars as a prelude to the world war, was one hand an expression of aspirational capitalist development and bourgeois class rule in all these states, it was an expression of the conflicting interests of the bourgeoisie among themselves as well as the clash of their development tendency with Austrian imperialism. Simultaneously, the nationalism of these countries, although at heart only the expression of a quite young, germ-like capitalism, was and is colored in the general atmosphere of imperialist development, even with distinct imperial tendencies. In Italy, nationalism is already thoroughly and exclusively a company plaque for a purely imperialist colonial appetite. The nationalism of the Tripolitan war and the Albanian appetite has as little in common with the Italian nationalism of the 1850s and 1860s as Mr. Sonnino has with Giuseppe Garibaldi.

In Russian Ukraine, up until the October uprising in 1917, nationalism was nothing, a bubble, the arrogance of roughly a dozen professors and lawyers who mostly couldn’t speak Ukrainian themselves. Since the Bolshevik Revolution it has become the very real expression of the petty-bourgeois counterrevolution, whose head is directed against the socialist working class. In India, nationalism is the expression of an emerging domestic bourgeoisie, which aims for independent exploitation of the country on its account instead of only serving as an object for English capital to leech. This nationalism, therefore, corresponds with its social content and its historical stage like the emancipation struggles of the United States of America at the outset of the 18th century.

So nationalism reflects back all conceivable interests, nuances, historical situations. It shines in all colors. It is everything and nothing, a mere shell. Everything hangs on it to assert its own particular social core.

So the universal, immediate world explosion of nationalism brings with it the most colorful confusion of special interests and tendencies in its bosom. But there is an axis that gives all these special interests a direction, a universal interest created by the particular historical situation: the apex against the threatening world revolution of the proletariat.

The Russian Revolution, with the Bolshevik rule it brought forth, has put the problem of social revolution on the agenda of history. It has pushed the class contradictions between capital and labor to the most extreme heights. In one swoop, it has opened up a gaping chasm between both classes in which volcanic fumes boil and fierce flames blaze. Just as the June Rebellion of the Paris proletariat and the June massacres split bourgeois society into two classes for the first time between which there can only be one law: a struggle of life and death, Bolshevik rule in Russia has placed bourgeois society face to face with the final struggle of life and death. It has destroyed and blown away the fiction of the tame working class that is relatively peacefully organized by socialism, which bragged in theoretical, harmless phrases but practically worshipped the principle: live and let live – that fiction, which was what the practice of German Social Democracy and in its footsteps, the entire International, consisted of for the last thirty years. The Russian Revolution instantly destroyed the modus vivendi between socialism and capitalism, created out of the last half-century of parliamentarism, with a rough fist and transformed socialism from the harmless phrases of electoral agitation, the blue skies of the distant future, into a bloodily serious problem of the present, of today. It has brutally ripped open the old, terrible wounds of bourgeois society that had been healing since the June Days in Paris in 1848.

All of this, of course, is initially only in the consciousness of the ruling classes. Just as the June Days, with the power of an electric shock, immediately imprinted the consciousness of an irreconcilable class opposition to the working class upon the bourgeoisie of all nations and cast a deadly hatred of the proletariat in their hearts whilst workers of all nations needed decades in order to adopt the same lessons of the June days for themselves, the consciousness of class opposition, it now repeats itself: The Russian Revolution has awakened a fuming, foaming, trembling fear and hatred of the threatening spectre of proletarian dictatorship in the entirety of the possessing classes in every single nation. It can only be compared with the sentiments of the Paris bourgeoisie during the June slaughters and the butchery of the Commune. ‘Bolshevism’ has become the catchword for practical, revolutionary socialism, for all endeavors of the working class to conquer power. In this rupturing of the social abyss within bourgeois society, in the international deepening and sharpening of class antagonism is the historical achievement of Bolshevism, and in this work – like in all great historical contexts – all errors and mistakes of Bolshevism vanish without a trace.

These sentiments are now the deepest heart of the nationalist delirium in which the capitalist world has seemingly fallen, they are the objective historical content to which the many-colored cards of announced nationalisms are reduced. These small, young bourgeoisie that are now striving for independent existence, are not merely trembling with the desire for winning unrestricted and untrammeled class rule but also for the long-awaited delight of the single-handed strangling of their mortal enemy: the revolutionary proletariat. This is a function they had to concede up until now to the disjointed state apparatus of foreign rule. Hate, like love, is only grudgingly left to a third wheel. Mannerheim’s blood orgies, the Finnish Gallifet, show how much that the blazing heat of hate that has sprouted up in the hearts of all small nations in the last few years, all the Poles, Lithuanians, Romanians, Ukrainians, Czechs, Croats, etc., only waited for the opportunity to finally disembowel the proletariat with ‘national’ means. From all these young nations, which like white and innocent lambs hopped along in the grassy meadows of world history, the carbuncle-like eyes of the grim tiger are already looking out and waiting to “settle the accounts” with the first stirrings of “Bolshevism”. Behind all of the idyllic banquets, the roaring festivals of brotherhood in Vienna, in Prague, in Zagreb, in Warsaw, Mannerheim’s open graves are already yawning and the Red Guards have to dig them themselves! The gallows of Charkow shimmer like faint silhouettes and the Lubinskys and Holubowitsches invited the German ‘liberators’ to Ukraine for their erection.

And the same fundamental idea reigns in the entire peace programme of Wilson. The “League of Nations” in the atmosphere of Anglo-American imperialism being drunk on victory and the frightening spectre of Bolshevism traversing the world stage can only bring forth one thing: a bourgeois world alliance for the repression of the proletariat. The first blood-soaked sacrifice that the High Priest Wilson, atop his omens, will make in front of the Ark of ‘The League of Nations’ will be Bolshevik Russia. The ‘self-determined nations’, victors and vanquished together, will overthrow it.

The ruling classes once again show their unerring instinct for their class interests, their wonderfully fine sensitivity for the dangers surrounding them. Whilst on the surface, the bourgeoisie are enjoying the loveliest weather and the proletarians of all countries are getting drunk on nationalist and ‘League of Nations’ spring breezes, bourgeois society is being torn limb from limb which heralds the impending change of seasons as the historical barometer falls. Whilst socialists are foolishly eager to pull their chestnuts of peace out of the fire of world war, as ‘national ministers’, they can’t help but see the inevitable, imminent fate behind their backs: the terrible rising spectre of social world revolution that has already silently stepped onto the back of the stage.

It is the objective unsolvability of the tasks bourgeois society faces that makes socialism a historical necessity and world revolution unavoidable.

No one can predict how long this final period will last and what forms it will take. History has already left the well-trodden path and the comfortable routine. Every new step, every new turn of the road opens up new perspectives and new scenery.

What is important is to understand the real problem of the period. The problem is called: the dictatorship of the proletariat, the realization of socialism. The difficulties of the task do not lie in the strength of the opponent, the resistance of bourgeois society. Its ultima ratio: the army is useless for the suppression of the proletariat as a result of the war, it has even become revolutionary itself. Its material basis for existence: the maintenance of society has been shattered by the war. Its moral basis for existence: tradition, routine, and authority have all been blown away by the wind. The whole structure has become loosened, fluid, movable. The conditions for struggle have never been so favourable for any emergent class in world history. It can fall into the lap of the proletariat like a ripe fruit. The difficulty lies in the proletariat itself, in its lack of maturity, or rather, the immaturity of its leaders, the socialist parties. The working class balks, it recoils before the uncertain enormity of its duty again and again. But it must, it must. History takes away all of its excuses: to lead us out of the night and horror of oppressed humanity into the light of liberation.