Lydia, Isaac and Rudy join Emmanuel Farjoun from Matzpen for a discussion on his 1983 piece Class divisions in Israeli society and how the divisions have changed in the present day. We discuss the changing strength of the Palestinians inside Israel and how that is reflected in their changing political aims, the differences between whiteness in the US and the construction of race in Israel, and the BDS movement internationally.

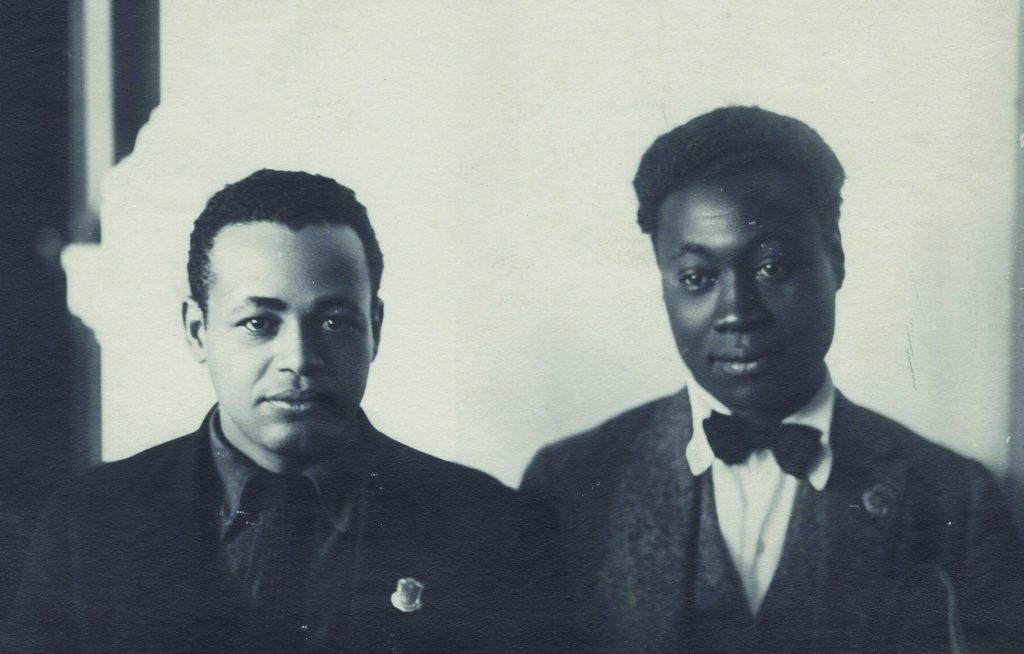

The African Blood Brotherhood and the Origins of Black Communism in the United States

Ian Szabo writes on the history of the African Blood Brotherhood as part of a broader tradition of black liberation that merged with International Communism after the Bolshevik Revolution.

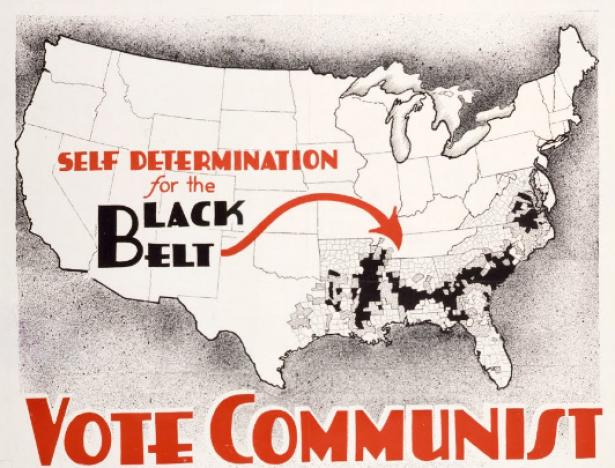

From 1928 to 1934 the slogan “Self-determination for the Black Belt” became the core of the Communist Party of the United States’ (CPUSA) approach to Black Liberation. A common understanding among the non-Stalinist left of this strategy is that it was cooked up by Stalin in the late 1920s in order to purchase a positive image for his bureaucratization of the Communist International (Comintern) as he ascended to power.1 Because of this narrative, among many others, we are left in the communist movement with a false dichotomy between national liberation and social revolution, despite the reality that self-determination has always been a necessary part of the revolutionary transformation of society. Surrendering it to Stalinism betrays a fundamental basis of revolutionary Marxism rightly referenced by Lenin: “[to] not be a secretary of a tred-union but a people’s tribune who can respond to each and every manifestation of abuse of power and oppression[.]”2

Nothing exposes this false dichotomy between socialism and self-determination better than the history of black struggle and its relation to the US Communist movement. To fully grasp this history we must look at how black radicals developed a tradition of struggle on their own and merged it with the practice of international communism in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. This requires looking at the history of the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), the first Black Communist organization, as well as its founder Cyril Briggs.

Briggs hailed from the Caribbean island of Nevis where he had refused to abandon his heritage as a black man and integrate into society with his lighter-skinned complexion.3 Alongside many other native West Indians of the period, he immigrated to the United States, eventually Harlem, in 1905. Due to a stutter that prevented him from being able to speak fluidly with others, Briggs chose to focus on writing rather than organizing, becoming an intellectual and writing for the Amsterdam News in 1912. The particular event that sparked his transformation into a Marxist was in the period just before the October Revolution in 1917; Briggs was faced with the ugly reality that Woodrow Wilson’s call for all nations to have the right to self-determination was bankrupt, revealed by the execution of 13 black mutineer soldiers in Houston, Texas.4 Although the unveiling of Wilson’s Fourteen Points later on would cause Briggs to waver, his primary political orientation would be towards the Socialist Party; and despite the SP’s tendency towards a class-first politics that failed to fully comprehend the oppression of African Americans, Briggs would put forward the argument that for black people, “no race would be more greatly benefited by the triumph of Labor”.5

Briggs’ disillusionment with liberal insincerity and movement towards socialist politics was accompanied by the development of what would become known as the Black Belt Thesis. During his last months at the Amsterdam News Briggs would write an essay entitled: “Security of Life’ for Poles and Serbs- Why Not for Colored Americans”, where he put forward the idea of a “colored autonomous state” somewhere in the upper northwest or far west. He chose these regions because he believed they had not been as settled as most regions in North America. Although there are differences in terms of the region this model aimed to use, this shows that the idea of an autonomous African American nation within the American continent was not simply a project cooked up by Stalin in the late 1920s. Rather than a foreign product, the Black Belt began as an attempt by an African American socialist searching to synthesize the aspirations of the African liberation struggle from which he came with the politics of revolutionary Marxism.

Eventually, socialist politics and opposition to WW1 would put Briggs in conflict with editors of the Amsterdam News. At the same time Briggs was forging friendships with the likes of Otto Huiswood, Grace Campbell, Richard B. Moore, W.A. Domingo, Hubert Harrison, Claude Mckay, and other radicals in Harlem. It was from this milieu that the journal Crusader was born. The period following the October Revolution in the United States saw a great deal of confidence and energy in the American left, signified in part by the Crusader and the ABB. This energy combined the turmoil that broke out after WW1 with the re-alignment of the global socialist movement and the birth of the Comintern. Briggs would be the intellectual powerhouse of the Crusader, continuing his arguments for the benefits of uniting with the workers’ struggle, while also theoretically uniting the African diaspora’s desires for self-determination with the Comintern’s goal of a Socialist Co-operative Commonwealth.6 For Briggs, Black liberation did not necessarily require a communist vision, but it was the preferable grounds or stepping stone by which to achieve it. In order to understand why Briggs believed that the communist vision of national liberation was superior to Marcus Garvey and the UNIA, we have to take a look at the radical transformations that had occurred in the Comintern.

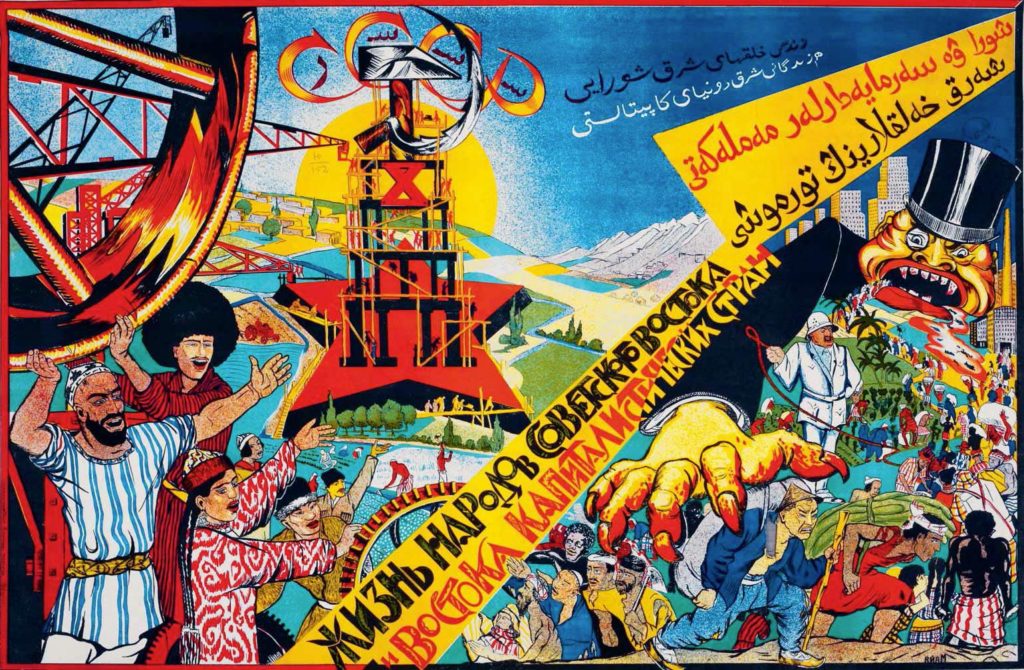

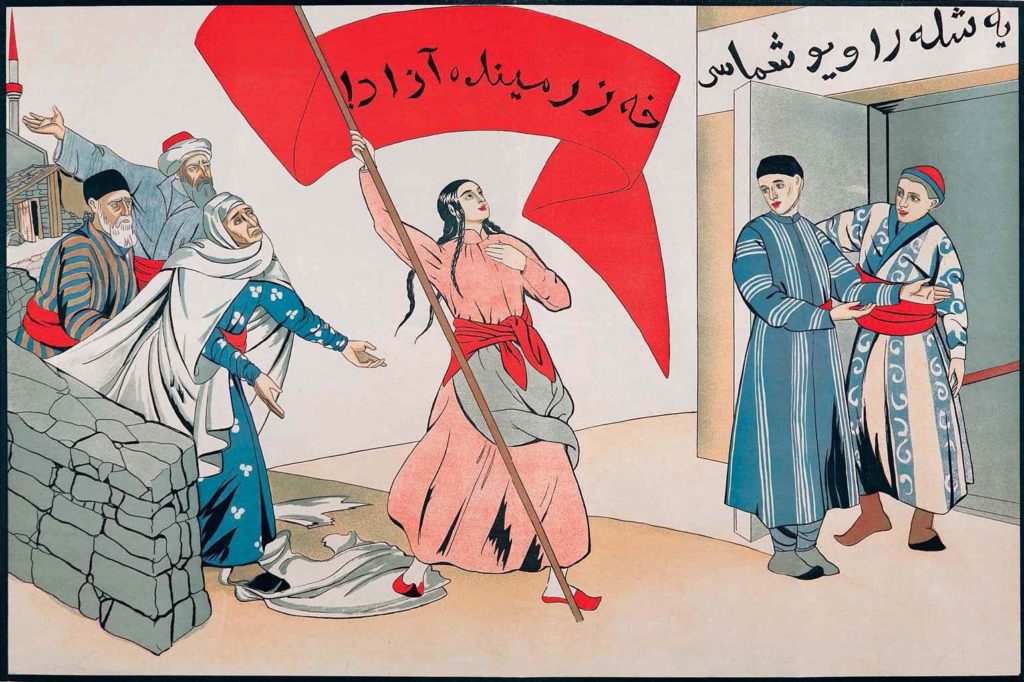

It cannot be understated how profoundly the formation of Third International widened the international character of the historical socialist movement, to which Briggs was responding. As Donald Parkinson has pointed out, “the Third International was an improvement of the Second. Marxists moved towards a truly internationalist universalism which saw the entire world as having agency in the revolutionary process and struggled politically against internal European chauvinism.”7 Taking direction from Nikolai Bukharin’s remarks on the subject, the resolutions put forward in the fourth congress of the Comintern cemented the point that the global communist movement had everything to gain through an alliance with oppressed people seeking national self-determination in the colonized world, as the task of the “[Comintern] on the national and colonial question must be based primarily on bringing together the proletariat and working classes of all nations and countries for the common revolutionary struggle.”8 This allowed Briggs and those around him to find a place they felt they did not have in the old socialist parties connected to the Second International, while also pulling them away from reactionary forms of nationalism that failed to properly deal with the nature of imperialism and colonialism.

At the same time that the Comintern was making strides towards a more forward-thinking international, Marcus Garvey was revealing his political commitments to reject socialism and even anti-racism. Already before the founding of the Crusader, W.A. Domingo had been fired from Garvey’s newspaper, Negro World, for espousing socialist politics. He would later become a collaborator with Briggs and co-found the Liberator with fellow ABB member, Richard B. Moore.9 According to Briggs in the foundational documents of the ABB, Garvey’s form of capitalist separatism would necessarily lead to the downfall of any attempt to gain self-determination, as inevitable capitalist crisis would wreck such attempts and sap morale from the liberation movement.10 A decade later, Briggs would more brutally relitigate this issue, pointing out that the Garvey movement failed to combat racism by ceding the American continent to white people, resulting in at least tacit collaboration with the Ku Klux Klan.11 In these criticisms, Briggs remained consistent with his argument that although socialism is not necessary for black for liberation, a socialist commonwealth on an international scale nevertheless provided the best chance for that task.

Although Theodore Draper characterized the ABB as being a typical iteration of the propagandist organizations of early century Harlem, it was equally familiar to the history of intellectualism in the worker’s movement, from Marx’s own Communist League to the circles the Bolsheviks emerged from.12 Of course, like any political organization it also had a program which formulated its basis on four points: “(1) the economic structure of the Struggle (not wholly economic, but nearly so); (2) that it is essential to know from whom our oppression comes… and to make common cause with all forces and movements working against our enemies; (3) that it is not necessary for Negroes to be able to endorse the program of these other movements before they can make common cause with them against the common enemy; (4) that the important thing about Soviet Russia… is… the outstanding fact that [it] is opposing the imperialist robbers who have partitioned our motherland and subjugated our kindred, and… [it] is feared by those imperialist nations.”13 The 1921 program fully articulated the class-based form of Black liberation Briggs sought to convey, utilizing the anti-imperialist commitments of the Comintern to build a bridge with the Bolshevik Party in Russia.

To fully grasp the historical importance of the ABB we must look not only to Briggs but to the entire membership. Drawn into the orbit of the ABB through her activism with the Committee on Urban Conditions among Negroes in Harlem, Grace Campbell was a social worker, court attendant, and prison officer convinced by the ABB’s call for socialism, black liberation, and decolonization.14 Alongside Hermina Dumont, Campbell was further radicalized by the international character of the communist movement. However, despite her involvement, the ABB was unfortunately an organization dominated by men, and so Campbell was relegated to secretarial tasks despite being on the “Supreme Council” of the ABB.15 Campbell dealt with the male chauvinism of the ABB through her involvement behind the scenes, as she held Supreme Council meetings and distributed the Crusader from her home.

According to McDuffie, Grace Campbell took the role of a mother figure for the ABB and much of the early communist left in Harlem. Not only a hub for the movement itself, Campbell’s home was open to anyone in need of food and shelter. It is true that this was a deeply gendered role to be given and taken up by Campbell, but the flipside of this is that it was also a source of power for a woman in the ABB able to “consciously construct and strategically perform this matronly persona to exert influence with women and to challenge the sexist agendas of black male leaders and to exercise influence in male-dominated political spaces”.16 Although much of this essay deals with the political orientation of the ABB, what is present in its history, as in most early socialist history, is a profoundly male-dominated dynamic which may be highly capable of dealing with the questions of decolonization and imperialism but fails to factor in, let alone fully integrate, the struggle of women workers.

A number of Grace Campbell’s comrades in her time as a socialist organizer would join her in Briggs’ ABB, but few would grow as close to Briggs himself as Richard B. Moore. A fellow radical from the Caribbean that found himself in Harlem, Moore came into Briggs’ orbit through his journalistic work and eventual founding of the Emancipator alongside W.A. Domingo.17 One point made by Moore himself about the ABB is worth keeping in mind: that although most of the history of the organization generally paints it as either a response to Marcus Garvey’s UNIA or a recruitment operation for the communist movement, this ignores the actual dynamics that produced the ABB. The reality is much more complicated, as many of the figures that made up the ABB had worked together prior to the organization’s formal founding. This means that the ABB was not necessarily a response to another organization but something which emerged from the intellectual and practical work black socialists had been committed to for years beforehand. Although many of these members certainly saw an ally in Leninism and the Comintern, their project had already developed its own political lines which the communist movement spoke to.

The campaign against Garveyism is a particular subject in which one can clearly see what Moore was getting at when he made this claim, as he did not fall in line with it. The aforementioned campaign was certainly in the right with regards to principled communist politics, but Moore refused to take part, preferring not to “[join] with the oppressors of your own people” and “betrayal of the right to speech.”18 As these debates were in the pre-Stalinized communist movement, the assumption that there needed to be a principled black united front with a right to criticism and free speech was prefigured within the movement and Moore’s conception of black socialist politics. If the ABB were simply made to respond to the UNIA or recruit black people to the communist movement, Moore would not have had any incentive to refuse to engage in this campaign, as it would have been perfectly consistent with the raison d’être of the organization. Instead, Moore’s response at the time was perfectly consistent with an organization that had always had its own agenda and vision of liberation.

In 1919-20, the ABB’s vision of liberation was encapsulated by a moment in Bogalusa, Louisiana, discussed by Moore in an article named after the city. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (UBCJ), International Union of Timber Workers (IUTW), and American Federation of Labor (AFL) had been organizing across racial lines in the city but were eventually attacked by an organization that synthesized both the redemption narrative and ethos of the Ku Klux Klan and the nationalism of the first red scare: the Self-Preservation and Loyalty League.19 Their target was the head of the union of African American sawmill workers and loggers, Sol Dacus, who would be saved by his shotgun-carrying white comrades, Stanley O’Rourke and J.P. Bouchillon. Gunfights broke out because of this, resulting in the deaths of O’Rourke and Bouchillon, alongside the president of the Central Trades and Labor Council Lem Williams and carpenter Thomas Gaines. Moore’s and Brigg’s own articles would have been known to the multi-racial workers of Bogalusa too, as they were avid readers of the Messenger and Crusader. After the killings, Moore’s article in the Messenger praised these men for having put lives on the line for their fellow black workers in his article “Bogalusa”:

Williams, Gaines, and Bouchillon have given their lives. O’Rourke imperilled his life, in the cause of true freedom. Not for white labor, not for black labor (though they died defending a [black worker]), nor yet for any race or nation, did they make the supreme sacrifice, but for Labor, that great university of fraternity of striving, suffering human-kind which though despoiled, despised, and rejected, alone holds promise for the emancipation of the race.20

This further demonstrates Moore’s argument that the ABB was a novel organization that neither responded to nor was subservient to another organization. Just as the theory of an autonomous African American nation was not cooked up by Stalin but a theory developed by Briggs, so too was the program of the ABB an expression of totally independent thinking of its members.

To further develop a rich image of the ABB we must look not only to understand its political dimensions, but also its cultural contributions. To do so we must look at another one of its members, the great poet Claude McKay. In the pages of the Liberator, Max Eastman’s newspaper, McKay would publish his seminal poem “If We Must Die” only two months after the founding of the African Blood Brotherhood, a poem which presented an explicitly revolutionary perspective which contained “no impotent whining… no prayers to the white man’s god, no mournful Jeremiad.”21

Shortly after its program was fleshed out and articulated, the ABB was integrated into the Communist Party. Earlier in May 1920, a convention was called among the various emergent communist parties that had not yet merged, the United Communist Party (UCP), Communist Party of America (CPA), and Communist Labor Party (CLP). The UCP had displayed a particular sensitivity to the question of Black liberation but the ABB remained officially distant due to the other parties’ lack of similar commitments. However, by 1921, Briggs would appear as a delegate for the ABB at the founding conference for the Workers Party of America (WPA) in 1921, later to become the Communist Party of the United States of America.25 Otto Huiswood became the head of the WPA’s “Negro Commission”, which was a good start for dealing with racial antagonism in the emerging party despite the persistent presence of neglect, and patronizing attitudes towards black members of the party.26

During this same period, the ABB experienced a bump in membership that forced it to choose between languishing in sectarian obscurity or fully integrating into the CP. A number of the leaders from Marcus Garvey’s UNIA had come on side to the ABB due to the former organization’s sketchy business practices, but these members were not particularly enthused with the idea of affiliating to the emerging Third International.27 To make things more difficult, the result of this growth convinced the ABB leadership to attempt a fundraiser for the creation of a new newspaper to named the Liberator, which not only failed to emerge but exhausted the continuation of the Crusader. With Briggs’ journal out of commission, he began working at the national office of the Friends of Soviet Russia in 1922, becoming an organizer at the Yorkville branch of the WPA, and managing to reclaim the name of his former journal in the form of the twice weekly Crusader News Service with the assistance of Grace Campbell.28 Although the UNIA continued to hemorrhage membership due to nonsense like bartering with the KKK, Briggs found himself unable to convince its membership to join the struggle for communism, and the ABB began to decline despite attempts to keep it afloat through sponsoring cooperative stores. By 1924, the ABB would become fully integrated within the WPA.

Ultimately, the ABB itself only existed for a short five years, but it left a huge impression on the American communist movement and its core membership would re-emerge in the nascent communist movement as the American Negro Labor Congress. Those who had built the ABB went on to become active organizers long after its demise, empowering African American workers throughout the southern United States. Their legacy is the idea that communism was, and still is, a vehicle towards self-determination and emancipation of all of the world’s oppressed. Solidarity of the entire international working class was at the core of their day to day political organizing, knowing that they could never be free so long as workers elsewhere were not.

Which Side Are You On?: The Challenge of the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution

The Ethiopian Revolution teaches modern leftists an important lesson about international solidarity, argues Ian Scott Horst.

Way back in 1848, the young Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels admonished in their Manifesto of the Communist Party, “Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things.” This basic prescription for political solidarity flows obviously and organically from the understanding of global political economy that they (and their ideological heirs) spent decades investigating, defining, and fighting for on street barricades. Marx and Engels diagnosed that the vast majority of the world’s population shared a mutual interest by virtue of its exploitation and oppression at the hands of a global class system, here in corrupt decay, there in bloody infancy. They suggested a liberatory class struggle as a path of resistance that was conveniently locked inside that global political and economic system and enabled by its own contradictions. To reject, indeed to overturn, that global system of exploitation and oppression of the vast majority of humanity by a tiny controlling minority of kings, political elites, and captains of industry, Marx and Engels prescribed not only moral outrage, but an understanding they called “scientific” of how those oppressed and exploited people could employ their vast majority in numbers and their strategic social relationship to the means of production to win the class struggle, and with it a better future for humankind based on cooperation and the communal good.

The phrase “Solidarity Forever” may have originated in radical trade unionism, but it was a damned effective compass for orienting one’s place in a combative world divided into potential comrades and bloodthirsty enemies. As leftist watchwords, the phrase reinforces an intuitive impulse growing out of the human experience of living and working together in a class-divided world, and neatly reinforces the deeper ideological explorations of theoreticians in the Marxist tradition. As a concept it rightfully suggests a deep connection between the daily struggles to survive, as experienced by the unpropertied classes and the political prescriptions of communist ideology. So why does it seem that so many of today’s heirs to Marxist tradition have discarded this time-proven compass when it comes to orienting themselves in today’s world of struggle? How did it happen that the first impulse of wide swathes of the Marxist left is to oppose the masses turning out into the world’s streets and avenues?

Leftists in the belly of the beast are morally (not to mention strategically) obligated to oppose the actions of our “own” imperialism. The dividing line this commitment creates is pretty easy to see in the separation of a “hard” left from a social-democratic one, even though the numbers of people identifying with either is much reduced in this post-Soviet century. But dialectical thinking should enable us to see that rejecting “our” government is actually not an automatic reason to express political support to every regime in conflict with the one we live under, and this is where much of today’s left seems to have stumbled away from the basic starting place located by Marx and Engels back in 1848.

It would be naive to suggest there are no differences in the mass popular mobilizations that have rocked the world’s streets in the last decade: The so-called Arab Spring and its stepchildren in Syria and Libya. Occupy Wall Street. Iran. Thailand. Zimbabwe. Venezuela. Nicaragua. The yellow vests of France. Hong Kong. But what unites these popular struggles is that, by degrees, much of the left reflexively rejected them out of hand, in some cases siding with the brutal police or military repression that would follow. Solidarity was discarded. In truth, some of these movements have had intensely reactionary elements, and in several cases that reactionary element is certainly at their core; but much of the left’s response was predictable, sudden, and utterly lacking in nuance, or importantly, any willingness to investigate the contradictory natures of these mass revolts or suffer any mild interest in the causes of mass grievance. The left has repeatedly rushed to identify the American CIA as the unquestionable locus of all global discontent. In several of these instances, the pretensions of the targets of mass resistance to some mantle of social progress were given greater credibility than the cries coming from the street. In many cases, the relationship of each country to the imperialist hegemon is factored larger than the class relationships within them. Let us not be naive: certainly, the CIA is engaged in subversion as a matter of routine. But what does it say about the possibilities for human liberation (and perhaps more importantly, about our abilities as professed revolutionaries to evangelize a universal message of revolt) that every spark of rebellion is reflexively dismissed? Put in another way, do “Black Lives Matter” only in the United States?

This phenomenon didn’t begin in the last decade. It really goes back to the halcyon days of left-talking military revolutionaries who dominated large swaths of the global South in the period between post-war decolonization and the fall of the Soviet bloc. With socialist revolution seemingly more distant than ever in the so-called liberal democracies of the global North, the left came to embrace many of these military figures with minimal critique or challenge, seemingly forgetting that printing up posters of Lenin isn’t quite the same thing as following his prescriptions for waging proletarian revolution or building socialism.

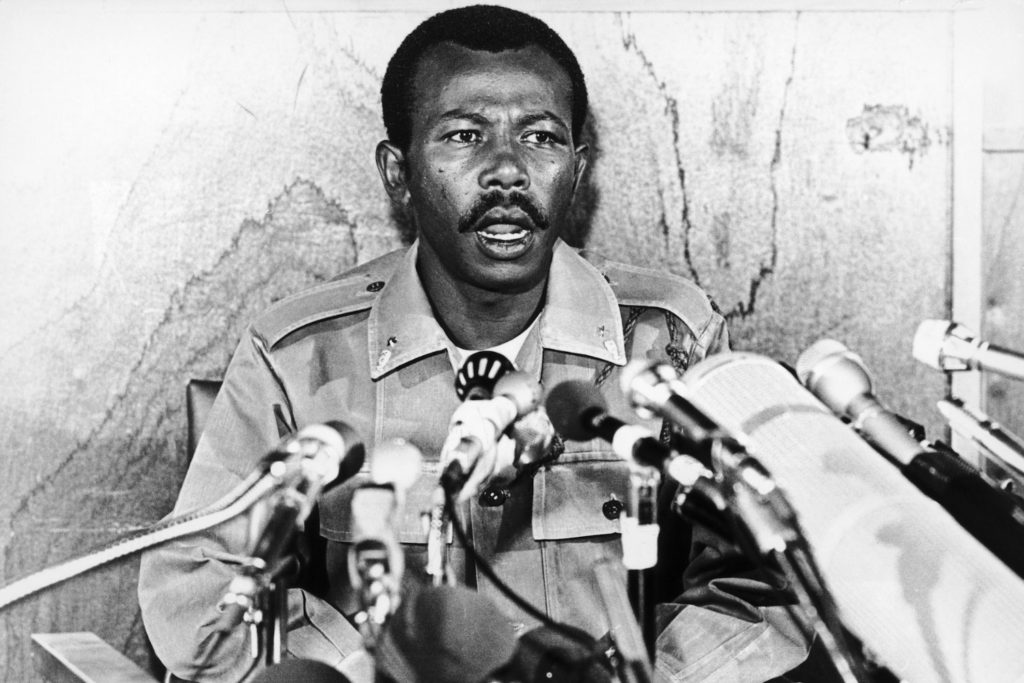

One of the clearer cases of this phenomenon — indeed one of the most tragic cases — was the embrace by much of the left of Lt. Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam and the military regime which ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991.

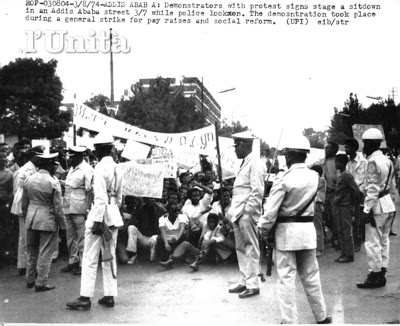

In February of 1974, a wave of labor strikes and mass protests swept the empire of Ethiopia. Tightly ruled by an aging Emperor Haile Selassie since the early decades of the century, now confronted with an increasingly harsh and vivid contrast between the haves and have-nots, the Ethiopian population stayed in the streets for weeks. They were soon joined by elements of the military which threatened a full-on mutiny. Taxi drivers, teachers, Ethiopia’s small industrial workforce led by what had been presumed to be a docile and captive trade union confederation in the pocket of the AFL-CIA, and most importantly, many thousands of dissatisfied high school and college students made economic and political demands, including that of popular democracy in the form of a people’s provisional government. There were mass demonstrations of priests and prostitutes, of minority Muslims; and the country’s vast peasantry began eyeing the land they worked in a variety of exploitative feudal land tenancy schemes. A country without political parties or press freedoms soon engendered a vibrant political culture in which underground publications written by communists soon dominated the national discourse.

In what has been described as a slow-motion coup, a committee of junior military officers known as the Derg began edging its way into the seat of power, forcing the autocrat to readjust his government repeatedly. They claimed that the spontaneous popular revolt needed direction and that the military was the only organized force in the country that could offer it. In September of 1974, the Derg pushed the emperor from power and shortly afterward proclaimed Ethiopia a state guided by “Ethiopian Socialism,” defined very loosely and not yet implying an imitation of, or connection to, the avowedly socialist countries of the Soviet bloc.

The new regime was ruled by a provisional military government, a triumvirate junta in which Mengistu was a junior partner. Mengistu had been trained in Fort Benning, Georgia, and displayed no apparent ideological sympathies. But ominously, in a year marked by remarkably little bloodshed, the Derg promptly executed sixty people, mostly prominent officials of the former regime and members of the nobility, but including a small number of leftists. In what was to set a pattern for government personnel changes in the Derg era, also killed was the head of the Derg himself, a liberal general named Aman Andom. While Mengistu remained a junior partner in the Derg, he was widely recognized as the agent of these executions. The military junta was now to be headed by another non-ideological figure, a brigadier general named Teferi Bente.

Over the next two years, the Derg government engaged in a number of revolutionary reforms, greeted with degrees of enthusiasm and skepticism by the revolutionary population. Some businesses were nationalized, but foreign and private investment was guaranteed. Feudal land tenancy was ended, but the land was turned over to the state, not the tiller. Students were sent to the countryside to evangelize Ethiopian socialism, but they, and the peasants they instructed, were punished for taking things too literally. The government tried to disband the independent labor movement and replace it with a captive state-run union that would focus on production and class peace. And all the while the regime continued the imperial wars against restive national minority populations, most notably the rebellious Eritreans in the country’s northern Red Sea region. The regime posed as anti-imperialist, but relied on U.S. aid, including all that military hardware being used against Eritrean peasants.

By the end of 1976, elements within the Derg lost patience with the quickly growing Ethiopian left which had continued its agitation for popular democracy and began to wage a brutal campaign of repression. This repression was met with violent resistance from the civilian left, which began its own urban guerrilla campaign against government officials guilty of acts of repression.

In February of 1977, Mengistu resolved some serious internal contradictions inside the regime with a preemptive coup d’etat, killing Teferi Bente and a handful of other officers of questionable loyalty. He immediately moved to make an alliance with the Soviet Union. He also unleashed what he would eventually christen as the “Red Terror,” a series of death squad campaigns against any and all civil opposition. While totals remain the subject of debate, the body count has been compared to that of the 1994 genocide in nearby Rwanda. By the time of the terror, the U.S.-trained Mengistu had become proficient at employing Marxist-Leninist rhetoric, and he claimed, invoking early Soviet history, that his purges were directed against counter-revolutionary “white terrorists,” which he defined variously as anarchists and Maoists as well as agents of imperialism and the former nobility.

When the quixotic and also avowedly Marxist-Leninist military leader of neighboring Somalia, Jaale Maxamed Siyaad Barre, invaded eastern Ethiopia and renounced his own Soviet sponsorship in favor of U.S. aid, Mengistu pleaded to Cuban leader Fidel Castro for assistance, and soon massive numbers of Cuban troops and Soviet bloc weapons flooded the country. Mengistu, with Soviet and Cuban aid, attempted to rally progressive global opinion against the Somali invasion, now marked as a proxy for imperialist meddling. Soon, Somali troops were driven out, and with massive donations of police surveillance technology from East Germany, the “Red Terror” found success by the end of 1978, wiping out all traces of opposition in the country’s urban areas.

A generation of political exiles fled the country, leaving behind a variety of guerrilla struggles polka-dotting the country’s rural expanses, one of which eventually snowballed into the rebellion that swept the regime from power in 1991. That rebellion also allowed the Eritrean rebels to consolidate their own victory and secede from Ethiopia. But in 1978 the future looked bright for Mengistu. He eventually built a captive state communist party (which he headed, of course), called the Workers Party of Ethiopia. Posters of himself, and Marx and Lenin were soon ubiquitous. Despite famine, economic disaster, and the occasional coup attempt, the regime lasted until about the same time as the Soviet bloc faltered. That global dust-plume of Soviet collapse undercut the stability of Soviet clients across the globe from Afghanistan to Benin, from Madagascar to South Yemen, from Kampuchea and Vietnam to Cuba; only the strongest survived and that did not include the Mengistu regime.

The great majority of the global left lauded Mengistu’s Ethiopia, accepting official government narrative as gospel. Socialist groups like the U.S. Workers World Party accepted state press junkets, interviewing regime members by day while nighttime neighborhood roundups left piles of bloody children’s bodies on street corners for the morning trash. Most Maoists and Trotskyists expressed degrees of critique, especially as regards the controlling influence of the USSR, and the global national liberation support movement anguished over the idea of the Cuban revolution suddenly in contradiction with the Eritrean national liberation struggle; but lasting orthodoxy seeping into 21st century leftist discourse holds that the Mengistu regime may have had its flaws, but it was another experience of Marxism-Leninism squelched by imperialism.

Most of the barebones narrative I have repeated above is not unlike the way much of the left recalls the Ethiopian Revolution in its totality, though perhaps I’ve been a bit more critical. They focus on the claims of the Mengistu and the Derg. They write off the dissent from the left. They are embarrassed by the violence, but since it was probably unreasonable infantile ultraleftists consciously or unconsciously acting in the interests of imperialism, it’s all well and good. As a model for socialism, well, it was a revolution from above, but it works that way sometimes.

As a verdict of history, let us be clear: an interpretation of Derg-era Ethiopia as actually socialist is completely shameful, and reflects miserably on the compass of solidarity used by the left. Nostalgia for Mengistu (still alive in a villa in Zimbabwe, by the way) is deeply and intensely misplaced. The global left embraced yet another left-talking military strongman, accepted his rhetorical claims at face value, and turned its back on what was one of the largest mass, civilian communist movements in African history. It’s worth remembering here one of the most useful axioms of Maoist praxis, “no investigation, no right to speak.” So let’s take a second look.

To really understand the Ethiopian revolution, one has to go back to at least 1960. While on one of his many foreign excursions, the emperor was briefly overthrown by military officers led by the Neway brothers. The rebellion was crushed and the Neways were executed, but it was a critical crack in the absolute rule of the emperor in a volatile period of continental decolonization. By 1965, a radical student movement formed the first of many clandestine organizations, the Crocodile Society, which organized demonstrations calling for “Land to the Tiller” and other democratic reforms. Against the backdrop of a growing world radicalization, resistance to the American aggression in Vietnam, the selfless albeit tragic guerrilla exploits of Che Guevara, the labor and student explosions of 1968, and the rise of a younger, more vibrant, New Left detached from Soviet orthodoxy, the Ethiopian student movement became the arena for revolutionary debate and discussion that was otherwise banned. Student publications were filled with nothing but theoretical articles debating the application of Marxism-Leninism to Ethiopia. This revolutionary student movement dominated academic culture in Ethiopia as well as among the many diaspora Ethiopians who were seeking higher education abroad.

The first Ethiopian left organization was formed secretly in France in 1968. Called Meison, the Amharic abbreviation for the All-Ethiopian Socialist Movement, it was the brainchild of an Ethiopian linguist named Haile Fida, who would become a notorious figure in the revolutionary era. The group had distinct views it argued for in the student diaspora, but as an organization, it remained completely clandestine until after the events of 1974. In 1969, a group of radical students led by Crocodile Society veteran Berhane Meskel Redda hijacked an airplane from Ethiopia to Sudan. They soon found themselves in revolutionary Algiers, were given a vacated pied noir villa by the Algerian government, and set up a base from which to coordinate revolutionary activities while they hobnobbed with Eldridge Cleaver and the Black Panthers and representatives of dozens of other global national liberation movements.

Things at home took a dark turn with the assassination at the end of the year of a popular student leader, Tilahun Gizaw, in what was presumed to be a government hit. A wave of repression killed many students, imprisoned more, and sent thousands of others abroad. Ethiopian student discourse took a serious turn: they knew a crisis was coming and with it the promise of a popular explosion, and they began to make plans to transform themselves from radical students to professional revolutionaries; they knew they needed a revolutionary party and started to plan how to build one. In 1972, they founded a second radical organization at a congress held in West Berlin, again in total secrecy. Calling itself the Ethiopian People’s Liberation Organization, its supporters were based everywhere there were Ethiopian students, from New York to Moscow, from Rome to Addis Ababa. It approached the most radical Palestinian organizations for military training, which it received. It competed for covert leadership of the movement with Meison, whose politics were not dissimilar but which had quite a different perspective. EPLO felt revolution was imminent, Meison prepared itself for a long march lasting many years.

It is true that the embryonic Ethiopian left did not lead the February 1974 uprising, though the ranks of people rising up included many young people who had spent their school years learning about revolution in the campus crucibles. Both Meison and EPLO immediately understood the importance of the moment, and most of their cadre who were based abroad returned home, where they began to publish and distribute regular underground newspapers and flyers. The most important of these was Democracia, published by EPLO, although that was, for the moment, left unsaid. They understood students couldn’t do it alone and they began to expand their social base. The revolutionary movement started to take off. It greeted the military coup with concern and suspicion; the welcome exit of the emperor tempered by the expectations about the predictable trajectory of a military regime. This was when the call for a people’s provisional government was formulated, at first supported by all factions on the left.

The left did not ignore the military. In Bolshevik fashion, they reached out to the military rank and file. EPLO even formed caucuses of revolutionary soldiers. Some oriented to various officers within the ruling military committee. Meison’s Haile Fida and one Senay Likke, a veteran of the diaspora student movement who had repeatedly clashed politically with partisans of EPLO, wound up becoming confidants of key Derg figures, including most importantly Mengistu, who was a veritable political tabula rasa packed with personal ambition. Shortly after some of the dramatic reforms announced by the regime, Meison dropped its calls for democracy in favor of cooperation with the military. Haile Fida and Senay Likke were soon referred to as the Derg’s politburo, and they and many of their followers were given portfolios in government ministries and charged with applying a socialist varnish to military rule.

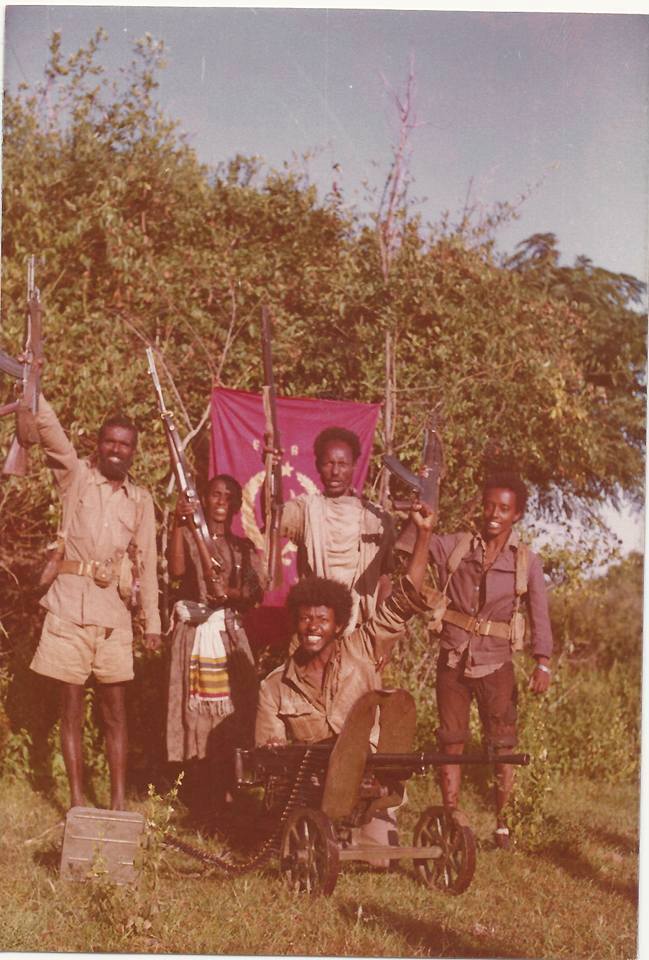

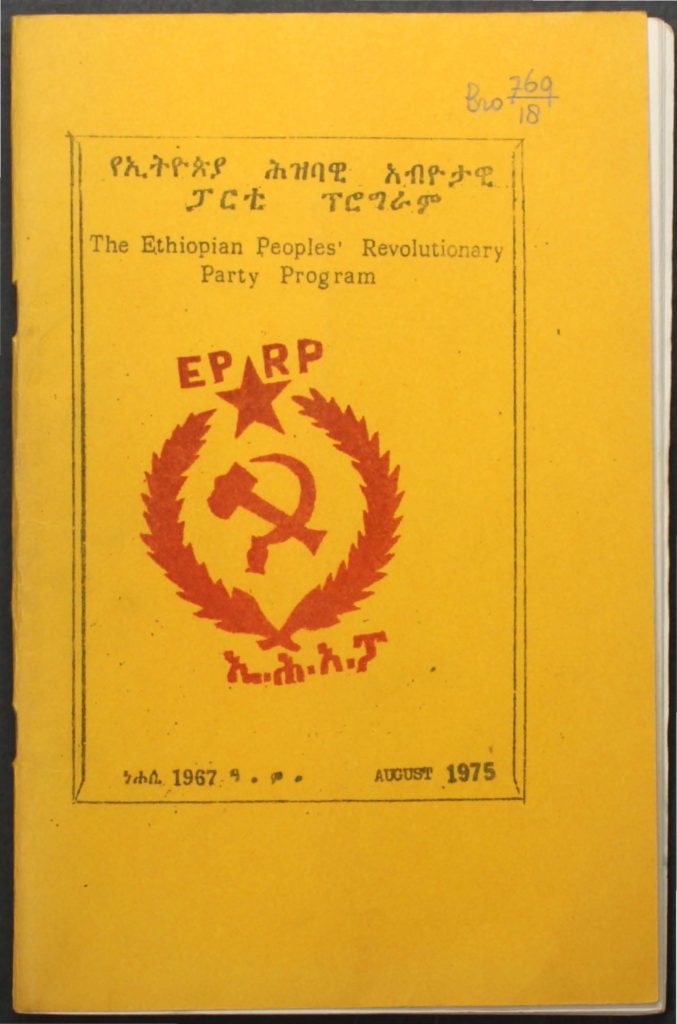

In 1975, EPLO transformed itself into Ethiopia’s first political party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party or EPRP. It had an elaborate nationwide network of clandestine cells and semi-open mass organizations. They established the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Youth League which attracted tens of thousands of eager revolutionary youth. They had a mass organization for women and their cadre kicked the CIA out of the Ethiopian labor movement. After that was suppressed, they formed their own red labor movement. They attempted, though ultimately unsuccessfully, to build an alliance with Eritrean rebels. At one point they were even accused of seizing control of national distribution of red chili pepper. At their height in 1976, they had thousands of members and tens of thousands more supporters and sympathizers. A rural base area in the north of the country was home to the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Army, which hoped to replicate the Chinese successes of waging people’s war and building peasant support in the countryside. EPRP has been called one of the largest communist parties ever seen on the African continent. It showed up to mass demonstrations with huge contingents carrying red flags, warning of the dangers of fascism from the regime and calling for the people to take power.

The politics of both EPRP and Meison started where one might expect for groups originating in the late 1960s: heavily influenced by Maoism, holding Che Guevara and the US Black Panthers in high regard. Meison tended more toward a kind of Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, but EPRP was ideologically quite iconoclastic. Its surviving propaganda materials reveal a commitment to revolutionary democracy and popular empowerment unparalleled in other left movements of the day. Surviving veterans of the movement talk of study groups where the reading lists may have started with Lenin and Mao, but ended with Frantz Fanon, new leftist economists like Huberman and Sweezy, and even Isaac Deutscher. Its ground-breaking 1975 program includes planks for workplace daycare to enable women to work and participate fully in society; it called for the recognition of the right to strike and laid forth a vision of a democratic society on a path to socialism. The EPRP’s formation threw off course the Derg’s own plans to form a political party; that didn’t fully materialize until 1984.

A comparison of how the EPRP organized for socialism with the way the Derg tried to impose it is stark. Again and again, Derg initiatives were clearly exercises in population control painted in red Marxist-Leninist language, devoid of popular empowerment but stressing obedience to “the revolution” and production. EPRP appeals called for the people to take what is theirs.

As Meison integrated into the state apparatus, simmering sectarian differences between the two groups became exacerbated. The EPRP accused Meison of compiling lists of its members to turn over to government agencies of repression, which were stocked with Meison supporters. The first person EPRP assassinated in reprisal for the government’s repression in late 1976 was a Meison cadre, a popular college professor, but one who was accused of having overseen a roundup of EPRP sympathizers.

1977 was a complicated year. Senay Likke lost his life collaterally during Mengistu’s coup. Meison eagerly participated in the first waves of “Red Terror” directed at the EPRP, but pulled back from supporting the government when Mengistu invited the Soviets in. Shortly before May Day, EPRYL youth preparing for celebrations were set upon by death squads and thousands were killed. During this period in general, the EPRP leadership was decimated. Its most important leaders were gunned down in the street; internal factionalism split the party, forcing Berhane Meskel off to the countryside to regroup and turning other factionalists into snitching enemies. Horrifying torture by the Derg including rape and genital mutilation was widespread. Parents were made to pay for the bullets used to execute their children.

When Meison broke from the regime, Haile Fida and its other leaders went underground. Meison lost its seat at the edge of power and joined the other victims of the terror. Thousands of its members and supporters were then killed or imprisoned, including Haile Fida himself. Ironically, both Berhane Meskel and Haile Fida were executed in the same prison in 1978, strangled by a graduating class of military cadets. Soviet advisors urged Mengistu to purge any traces of Maoism or Chinese influence, and so the last remnants of the civilian left were exterminated. By the end of the year EPRP was reduced to a struggling guerrilla force in the countryside; it survived through the end of the Derg era, but was banned by the new government. That, as they say, is another story; EPRP today calls itself social-democratic but it jettisoned the most radical Marxist parts of its program in the 1980s.

EPRP, Meison and the Derg all waved hammers and sickles. But an investigation of what they meant by those hammers and sickles reveals conflicting visions of socialism and a fundamental dishonesty on the part of the Derg. The Derg was always the creature of the military officer corps: it propounded a theory of the “men in uniform” meant to rationalize the role of the military as agents of social change. The Derg was not made up of the soldiers of the 1917-era Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies, it was the creature of Kornilov’s officer corps. Like the emperor before them, it repeatedly and openly said that the Ethiopian people were not ready for democracy. It acted out of expediency, not principle. The EPRP’s base included a layer of the urban petty bourgeoisie, but the Derg’s base included the massive layer of lumpenproletariat displaced from the countryside and crowding Ethiopia’s cities who could be counted on, sometimes mildly coerced, to turn out to pro-government rallies. But even with the transformation of the regime from a provisional one to a formalized single-party state over the course of the 1980s, military figures kept a tight grip, making up the majority of “Workers” Party membership.

The EPRP certainly deserves scrutiny. It can be said in some ways that they were too little too late, and all their study and preparation failed to prepare them for the heavyweight of repression that was to fall on them. Although they made ingenious plans for clandestine organizing and had a clear vision of their final destination, they ultimately failed at people’s war and their detour into urban guerrilla war and terrorism lost them support among those concerned generically about “violence.” They wavered when confronted with strategic choices for a united front to keep the revolution on track.

The revolutionary left achieved hegemony over the Ethiopian student movement at a time when that movement was hugely influential, and this was remarkable. None of its factions believed that students would themselves be the vanguard of a revolution per se; they studied Lenin’s writings on the party and understood the limitations of student organizing. The whirlwind of events confronted the left with an array of choices for breaking out of their demographic limitations, but also a shrinking horizon of possibility. Some turned toward organizing the proletariat and the peasantry directly from their midst and simply ran out of time. Others turned toward the revolutionary state for leverage in organizing society from above; they would find themselves outmaneuvered and paying with their lives at the hands of institutions they helped create.

Those interested in reading more about the EPRP and Meison may have to wait for my own book-length documentary history to see the light of day; for now, the Ethiopian section of the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online hosted by the Marxist Internet Archive is definitely worth a perusal. The bottom line, however, is that an understanding of revolutionary Ethiopia — perhaps more accurately labeled counterrevolutionary Ethiopia — is not possible from taking the words and visuals provided by Mengistu and his allies at face value. There are complicated ideological issues here that a short article like this one can’t address. But there are also facts. And the worshipful appetite of segments of the left for a military ruler who held on to power by suppressing the left, by suppressing ethnic dissent, really makes a travesty of the foundations of our commitments as communists.

What happened in 1974 was a real revolution at the conjuncture of contradictions in Ethiopian society. That revolution continued with critical mass support for a few years, but the process was hijacked by a brutal military that sought to control and channel it for their own power. In 1991, the masses of Addis Ababa enthusiastically welcomed the toppling of the massive Lenin statue that had been supplied by North Korea in 1984. This is the cost of getting it wrong: socialism is remembered in Ethiopia as the dark time when untold thousands of people, including children beyond counting, lost their lives at the hands of people who claimed to be acting in the shadow of Marx and Lenin.

People have been in the streets around the world in the past decade in sometimes surprising places. Are some reactionary while others revolutionary? Sure. Without a dominating ideological resurgence of clear class-based revolutionary praxis, that’s likely to continue. But if you’re gonna pick a side that is a government against its people, you’ll need to have a deep and factual understanding of why and be prepared to fit that answer into an ideological matrix of human liberation. Or maybe you’ll have some explaining to do if you keep calling yourself a Marxist.

A Short Suggested Reading List on the Ethiopian Revolution:

-

- John Markakis and Nega Ayele, Class and Revolution in Ethiopia, Red Sea Press, 1978. Still in print I think. Markakis is a respected Ethiopianist academic; Nega was a former student activist and a key member of the EPRP who perished in the terror. While dated, contains lots of factual analysis and a healthy suspicion of the Derg.

- Babile Tole, To Kill a Generation; Free Ethiopia Press, 1989/1997. Out of print but PDF widely available online (see EROL link above); Babile Tole is the pseudonym for a collective of EPRP insiders.

- Hiwot Teffera, Tower in the Sky; Addis Ababa University Press, 2012/2015. A little hard to find in the US, but an easy, moving read. One of the many memoirs by veterans of the period. Somewhat controversial in a world where the arguments and tragedies of the 1970s remain in living memory among survivors. The bibliography of my own work references something like a dozen of these memoirs, all worthwhile reading.

- Kiflu Tadesse, The Generation, Volumes I and II. Out of print and expensive, these two volumes by one of the highest-ranking EPRP leaders to survive the period contain extraordinarily rich detail about the party’s history, politics, and organization. Also somewhat controversial.

- Hama Tuma, The Case of the Socialist Witchdoctor And Other Stories, Heinemann paperback, 1993. Out of print, but not hard to find. Bitter, moving, satiric fiction about the revolutionary era from the pseudonymous Hama Tuma, actually also a founder of the EPRP.

- Left-wing books on the subject written during the Derg era by Fred Halliday, the Ottoways, and René Lefort are rich in detail but marred by also being rich in excuses for the Derg. More modern post-Derg works on the revolutionary period have their merits but are generally marred by anti-communism. Solomon Ejigu Gebreselassie’s The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, 1975-2008 from Red Sea Press is still in print and covers a lot of this ground but is a sort of diaspora polemic with the modern remnant of the EPRP.

Ian Scott Horst is an independent communist living in Brooklyn, New York. He has been a supporter of a variety of defunct groups including the post-Trotskyist Revolutionary Socialist League, Lavender Left, Queer Pagans, and the post-Maoist Kasama Project. He recently completed a book-length documentary history of the Ethiopian revolutionary left and is currently shopping for a publisher. Updates on his research and the progress of his book can be found at his Abyot—The Lost Revolution blog.

Reparations and Self-Determination: Loosening the Black-Belt

Renato Flores argues for self-determination and reparations for Black Americans as a key part of the revolutionary struggle in the USA.

I

The uniqueness of the Black condition in the United States is hard to understand for anyone foreign to the Americas. Its complexity is often lost in semantic distinctions on whether Black Americans are a Nation or not. A typical first avenue to assess Nationhood is to mechanistically apply Stalin’s checklist: “common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture.”1 When this is applied to the Black nation, the obvious question becomes: where is the territory?

A dismissive answer would be to say that there is no land because population migration has rendered the Black Belt thesis obsolete. This answer is not only insufficient, but it is also hardly new: it has been leveled at the Black liberation movement since its inception in different shapes. Harry Haywood, the CPUSA’s leading theoretician on the Black Nation repeatedly answered this critique in the decades between the 20s to the 60s.2 As he presciently pointed out, migratory fluxes and the passage of time had done nothing to integrate black people. Looking from the era of Trump and mass incarceration, it is clear that this point still holds: Black oppression morphs in shape, but it never disappears.

An alternative answer is the Black Belt still exists in the shape of the 60-70 counties that still have a Black population of over 50% and their surroundings. This answer is poisoned, not only because there is a limited geographical continuity between these counties, especially those outside the Mississippi basin and the plantation belt in the South, but because it implicitly accepts the settler division of this continent. It also doesn’t outline how land claims from the Black Nation are compatible with Indigenous claims. Even worse, mere accounting of people could very well be leveraged against American Indian struggles to deny their validity when they occur in territory where settlers are the majority.

Furthermore, even if one accepts that the Black Nation has its territory in the Southern states, it is hard to outline a path to self-determination while this land is held by an intensely racist ruling class. This is barely a new objection: Cyril Briggs, who pioneered the idea of a Black Nation on North American land chose the far West for his Nation to avoid this problem. The boundaries of the Black Nation were never clearly outlined by Haywood and the CPUSA, knowing that even if a black nation-state was formed, it could end up landlocked by Jim Crow states and isolated. The CPUSA insisted on the black belt hypothesis despite its impracticality because it was necessary to check off land in Stalin’s checklist. The right to a separate state requires land, which complicated self-determination. To remain faithful to the Black Belt thesis required spending significant time addressing geographical questions.

The answer to this antinomy is to move past land. One cannot fully grasp the concept of a nation materially: the persistence of Black nationalism despite internal migration means that the “idea” of a Nation is more resilient than land. Benedict Anderson defines a nation as a socially constructed community, imagined by the people who perceive themselves to be part of the group. In this sense, it is hard to deny that Blacks in the United States constitute themselves as an “imagined community”. Slogans of “buy black” or “black capitalism”, as well as black separatist groups such as the Nation of Islam are very alive today, and they speak more to the Black masses than socialists do. Those who see in them petit-bourgeois deviations are behaving like their counterparts a hundred years ago, which were hit by the realities of Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa” mass-movement. Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association was able to temporally attract over a million black people while communists struggled to recruit blacks at all. By looking at its aftermath, Harry Haywood acknowledged the mistakes of the communist movement and formulated the first comprehensive call for self-determination in the Black Belt.3

So what can we say about the Black nation today? And what is the minimum socialist program for Black self-determination? To begin to understand this, we must remember two things. First, that the United States was founded on (white) race solidarity, and by default excluded black self-determination. Second, that the debt of “forty acres and a mule” remains unpaid, causing a wide economic disparity between Black wealth and White wealth. Both of these problems are discussed today, but never together. Trying to answer one at a time is insufficient; we need both economic and racial justice or will end up getting neither.

II

Anti-blackness is embedded in the DNA of the United States. The exclusion of black people from the community of whiteness offers fertile ground for a Black “imagined community”. Unlike layers of Asians and Latinos, Blacks will never have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness in the United States. That would render the whole category of whiteness obsolete. Racial solidarity, the main stabilizer of class struggle, would disappear. The persistence of whiteness explains the persistence of Black nationalism.

The way race is constructed in the United States has few parallels, but they exist. In Traces of History, Patrick Wolfe elaborates on the founding of the United States, drawing similarities between the use of antisemitism to forge nations in Europe in the early 1900s, and the use of anti-blackness to forge race solidarity in the US. The question of European Jewry was tragically resolved through the horrors of the Shoah and the ethnic cleansing of Palestine to establish the ethnostate of Israel. Following Wolfe, we can look at the debates around the Jews in the 1900s to find ways to answer the Black question.

In the early 1900s, the largest Jewish socialist organization was the Bund, located in Eastern Europe and comprising tens of thousands of Jewish workers willing to fight for their liberation.4 The Bund called for Jewish self-determination, but in a different shape from that associated with the Bolsheviks. Its prime theorist, Vladimir Medem, drew inspiration from the Austromarxist school of Karl Renner and Otto Bauer. Medem demanded Jewish “national and cultural” autonomy, with separate schools to preserve Jewish culture. His brand of nationalism was of “national neutrality”, and opposed both preventing and stimulating assimilation. He just refused to make any predictions on the future of Jews.

Otto Bauer’s writings on the national question and self-determination are more remembered today by Lenin’s polemics than on their own right. Lenin was correct to criticize Bauer for denying territorial self-determination to nations within the Austro-Hungarian empire, and restricting them to “national cultural autonomy”. But by throwing away the baby with the bathwater, a different definition of self-determination and approach to nationhood was damned to obscurity. Bauer’s historicist definition of a nation as “a community with a common history and a common destiny” remains underappreciated in the Marxist tradition, even if it has influenced people like Benedict Anderson.5 Medem drew from the Austromarxist school even if Bauer denied nationhood to the Jews on the grounds that they lacked a common destiny. By limiting his look to the Western European Jews, Bauer failed to see the power of his approach where it was adopted.

The Bolsheviks also failed to capture the intricacies of the Jewish nation. Lenin framed the Jews as something more akin to a caste than a nation. Stalin dedicated an entire chapter of his National Question to polemicize against the Bund and the Jewish nation. By contrasting the cultural autonomy demands of the Bund to the struggles of Poles and Finnish for territorial self-determination, Stalin found the Bund’s demands as insufficient under Tsarist authoritarianism and superfluous under democracy. He also claimed that Jews were not a nation because “there is no large and stable stratum connected with the land, which would naturally rivet the nation together, serving not only as its framework but also as a ‘national market.” Both Lenin and Stalin saw assimilation as the only solution and shut the doors on Medem’s middle way. This meant that even if the Bund started its history closer to the Bolsheviks, they were eventually repelled towards the Mensheviks who accepted their nationalist vision.

In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the Bund would undergo several splits and realignments. Their program for Jewish self-determination never saw full and consistent implementation. In a cruel irony, both Bolsheviks and Austromarxists were proven wrong by the Jewish version of Garvey’s return to Africa: Zionism. The return to a mythical Jewish land was able to take hold among sections of Eastern European Jews, showing that they were never fully integrated. Zionism not only matched the mass appeal of Garvey, the support of Western imperialism made it achievable. When confronted with this serious ideological rival, the Bolsheviks realized their mistake and attempted to provide a “Jewish autonomous oblast,” giving a land basis to Jewish self-determination within the USSR. But that was a large failure: at its peak, only fifty thousand Jews moved to the oblast in Eastern Siberia. When offered second-rate Zionism, why not choose the original?

III

If we read Stalin’s original criticism of the Bund, we can find many parallels to present critiques of Black nationalism. Applying his rigid framework to black people can lead us to the absurd conclusion that the Black nation, and the impossibility of racial integration in the United States, is contingent on the continued existence of a small number of sharecroppers connected to the land. Haywood was too faithful to his party to abandon the narrow confines of Stalin’s definition of nation and adopt a different one. Thus, he was forced to repeatedly argue for the persistence of sharecropping rather than abandon the Black nation. His opponents never abandoned the same framework, and the real debate became obscured by the interpretation of geographical statistics.

We must recognize that this is an absurd either-or. We can try to rescue the idea of “national personal autonomy” as a way of granting self-determination when the land basis is not sufficiently solid, and using it as a way to “organize nations not in territorial bodies but in simple association of persons”. This provides a working program for Black self-determination which avoids the question of the land. Indeed, self-determination means nothing without the right to separate, and the right to organize blacks separately has been demanded by many revolutionaries throughout history. This includes someone like Martin Luther King, who said that “separation may serve as a temporary way-station to the ultimate goal of integration” because integration now meant that black people were integrated without power.6

Socialists should not be afraid of this: Black Nationalist associations such as the Black Panther Party or the League of Revolutionary Black Workers have been amongst the most revolutionary forces of the United States. A reason they were so successful was their ability to organize separately in their initial stages, and reach out to other movements on their own terms. But it is essential to remember that separation is being demanded by those communities, and not enforced. Separation can very well be used to enforce racial injustice as shown by the use of “separate but equal” schools.7

However, self-determination alone does not address the wealth disparity between races. Experiments in black self-determination like those being conducted by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement in Jackson, Mississippi are bound to fail due to economic constraints. Black communities lack the wealth necessary to jump-start their own structures. This is the second pillar that holds up the existence of the Negro nation: the debt owed from the legacy of slavery. When the shadow of the plantation enters, the analogy between Blacks and European Jews breaks down, and the question of reparations becomes central.

IV

The most honest case against reparations is that of Adolph Reed.8 Reed never denies that the legacy of slavery has caused Black people to be at a significant economic disadvantage. However, he denies that the demand for reparations has progressive potential, and attributes it to petit-bourgeois nationalism (sound familiar?), where the middle classes attempt to rebuild a destroyed black psyche through back-room deals, in place of mass organizing.

Reed fails to see the potential for reparations to actually coalesce in a mass revolutionary movement. But fighting white supremacy need not begin from a revolutionary point. The original demands of the Montgomery bus boycott of the 60s were as mild as first-come, first-served seating, and did not even ask for desegregated buses. But anti-racism becomes a genuinely revolutionary movement by necessity if it is to reach its endpoint. We only have to observe MLK’s slow transformation to anti-capitalism. Every revolutionary movement in the history of this country has been led by black people and anti-racist organizing, be it the Reconstruction period after the Civil War, the strikes leading to the formation of the AFL-CIO, the second Reconstruction of Civil Rights or the Black Panther Party. History tells us that any path to a radical transformation of this country must go through anti-racist, anti-imperialist organizing or it is bound to stop halfway before reaching its goals.

Contrast reparations with Medicare for all. Medicare for all has the potential to immediately transform the lives of millions of people for the better. But Medicare for all does not fundamentally challenge capitalism. Sanders regularly points to Western Europe and other “industrialized” countries as examples that universal healthcare is possible (Cuba is a notable example he never mentions). As he accidentally shows, it is a demand that is perfectly possible to accommodate within the realms of capitalist societies. Settler-colonial states such as Canada and Australia provide universal access to healthcare for the “community of the free”. These countries are no less settler-colonial if they provide their settler-citizens with healthcare. The dispossession of indigenous people continues unabated, and Australia’s notoriously racist immigrant policy still holds. If this isn’t the definition of trade-unionist, economist demands then what is?

Decommodification of essential commodities is just ordinary Keynesianism: a way for capitalism to manage the inherent contradiction between laissez-faire economics and the existence of the hopeless poor.9 As Keynes and other economists faced down the Great Depression, the consensus became that state would mitigate the worst excesses of capitalism to save “the thin crust of civilization”. They would create poverty with dignity, incorporating the rabble into civil society by using government programs to provide them with their basic needs. The programs of the New Deal, and the creation of the post-war European welfare system are surely the largest bribes ever given to the working class, with the bill paid by the Global South. Guillotines were avoided, Keynesianism stabilized capitalism for over three decades. The proto-revolutionary proletarian rabble was turned into the social-democratic industrialized “middle” class, one that had gained an interest in preserving the system.

In 2019, neoliberalism has recreated on a massive scale the figure of the hopeless poor. Bernie and other progressives face the Long Recession with measures like Medicare for all and $15/hour minimum wage. “Democratic socialism” is the new word, twisted and redefined to mean anything. While this term means many different things for many people, the underlying ideal for Sanders is a system where we can manage the contradictions of capitalism and give it a human face through state intervention. Sanders tries to attract Trump voters by making class-based demands around which to unite the “99%”. Many socialists are trying to take advantage of Sanders’ cross-party appeal to revitalize the forces of revolutionary socialism. But as Lenin recognized, workers will not simply become revolutionaries by fighting for economist demands. Focusing on Medicare for All fails to outline a vision for a new society, and winning it could mean instead that sections of workers become disinterested in further challenging the system. The post-war era shows the limit of economist demands. Social-democratic Sweden went as far as the Meidner plan, a vision to turn the means of production into workers’ control. The Meidner plan failed, and business began its counteroffensive. Workers were too invested in the system to significantly challenge this failure, and as of today, capital has slowly chipped away at many of the historical gains of Swedish social-democracy. As Lenin stated in Left-Wing Communism, revolutions can only triumph “when the “lower classes” do not want to live in the old way”.10 In this case, the “old way” was good enough, and workers did not fight to move from “social democracy” to “democratic socialism”.

In a country like the United States, revolutionaries must fundamentally look to challenge the political structure and form a broader vision of how the system should look. Sanders’ race-agnostic politics do nothing to address domestic white supremacy or the pillaging of the Global South. Sanders is right in that universalist policies such as a $15/hour minimum wage will primarily help people of color. But this does not do anything to change systemic discrimination. We have enough evidence to show that remedies in policing do not address the institutionalized white supremacy of law enforcement. Medicare for All might transform the way white supremacy is enforced in the healthcare system, but it is naive to think that it will eliminate it.

Centering race-blind social-democratic projects as a model is not enough. The Swedish social-democratic project was based around a relatively homogeneous “community of the free”. Today it shows deep cracks due to its inability to deal with the cultural and racial diversity immigration has brought in. Universal politics assume that all subjects conform to the same standards, and believe in the same project. With the racial diversity of the US, any universalist race-blind project is doomed if it does not explicitly address the faultlines of the working class. The most marginalized sections will simply not trust economist projects to include them. There is over a century of failures to attest to this, from the failure of Eugene Debs’ Socialist Party to significantly attract black members to Sanders’ inability in 2016 to compete in the Southern states. And even if we do win universalist demands, the cracks will show up later and will be used to reverse any gains. We just have to remember how Reagan leveraged the “welfare queen” that had an explicitly racist subtext.

V

Instead of a form of subjugation that can be remedied by economic means alone, we have to recognize the political character of white supremacy. The issue of slavery is at the forefront of this election cycle. A Trump presidency is the elephant in the room: the Obama presidency did not mean that we are post-racial. The 1619 project is actively shaping how people think of the United States, tying the foundation of this country to the first shipment of slaves. Led by the New York Times, it is receiving attention from the highest spheres. Some type of cosmetic reparations will feature in a 2020 Democratic platform as an attempt to attract back the black voters the Democrats desperately need. Several candidates, the most notable of which was Marianne Williamson, have proposed comprehensive platforms on the debate floor.

An electoral platform centered around destroying whiteness through indigenous justice and reparations is of paramount importance for socialists today. Some plans are simply not worthy of the name of reparations. Black self-determination plays a key role in this platform to both decide what reparations actually mean, and what to do with the money. Tax credits do nothing to address collective injustice, while the US government coming in to repair infrastructure in majority-Black neighborhoods does not address Black self-determination.

As socialists, we should never oppose reparations, as that would mean isolating us from the Black masses. We have to remember how the Bolshevik’s refusal to address the Bundist concerns led them to the hands of the Mensheviks. A debt of forty acres and a mule is owed, and this is the whole material heart of the Black national question. We should center that it is essential for Black people to decide on what reparations mean. We should not be afraid of not having a seat at that table, because that either means that we do not have enough Black members in our parties, or that our members are not fighting for proletarian hegemony within the Black movement. A council for deciding how and where to apply reparations can be a seed to building alternative power if wielded correctly.

Reparations are not an end-goal but we can use them today to ground the fight for black self-determination and to struggle against whiteness. Ultimately, any non-reformist reform cannot remedy the US’s flaws of racism. This assumes that atonement can be reached within the confines of the current nation-state. The United States’ sins are not a choice it can reverse, they are deeply embedded in the DNA of this country. The platform to cure the character mistakes of the United States can only be fulfilled by the dismantling of the settler-colonial white supremacist structure. Even a comprehensive platform for reparations in its present state is not viable in the current political climate. The same way that “Black Lives Matter” caused a proto-fascist antithesis in the shape of “Blue Lives Matter”, a reparations movement should expect to be attacked both rhetorically and physically.

Even the most flawed reparations platform recognizes the issues of white supremacy as central to the United States and transcends economism in a way Sanders is not able to. While Sanders just wants to make an American Sweden, our movement must go much further. We need a vision for a better world, beyond wonkiness and towards a greater inspiration if we are ever to escape the confines of capitalism. Even if the first and second Reconstructions were unfinished revolutions, they changed society much more profoundly than the New Deal ever did by destroying slavery and Jim Crow.

At the same time, these anti-racist revolutions unleashed collectivized hatred in intense ways that contributed to their later failures. Fascism is capitalism in decay, and reactionary elements are inevitable in any pre-revolutionary situation. Socialists need a comprehensive economic program to pacify white reaction by offering to pay better than the wages of whiteness. Revolutions based on rural or marginalized people can succeed, like Cuba, fall short like Nepal, or fail completely like Peru, depending on their ability to attract the urban wavering classes. Ultimately, any successful socialist program in the United States must incorporate both racial and economic justice. In the first case, to center it politically, in a Leninist manner. In the second, to provide an incentive for the wavering classes to follow.

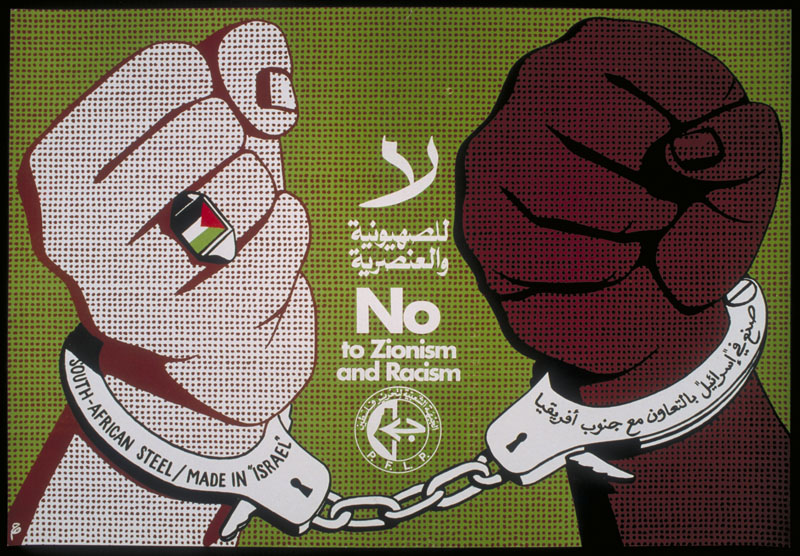

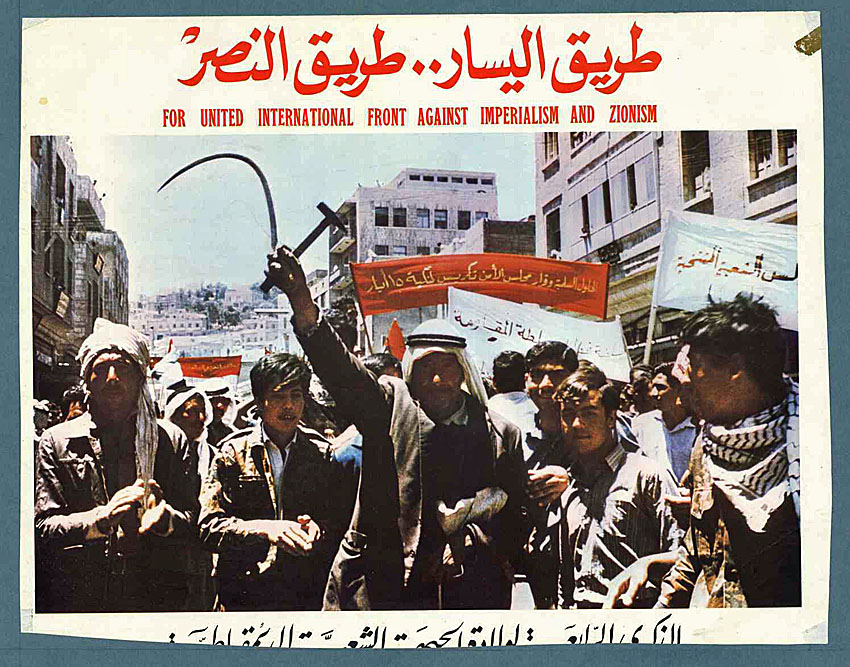

“Consistent Advocates of the Arab People”: Soviet Perceptions of and Policy on Palestine

Abdullah Smith argues that the USSR’s relation to Palestinian national liberation was more about realpolitik than earnest dedication to the cause of the Palestinian people.

The relationship between the Soviet Union and the Palestinian national liberation struggle was a highly ambivalent one set against the backdrop of the Cold War. As the Western and Eastern Blocs vied for influence in the Middle East, the Soviet Union proclaimed in the late 1960s that they would resolutely support — materially, diplomatically, and ideologically — the Palestinian people in their war of national liberation, and the broader Arab world against “imperialism and Zionism.” This position, they proclaimed, stemmed from the Marxist-Leninist positions of “proletarian internationalism” and “self-determination of nations.” However, like much of Soviet foreign policy, reality was far different from rhetoric. Upon further examination of Soviet actions toward Palestine, this supposed solidarity with Palestinian revolutionaries was not one of revolutionary internationalism and anti-imperialism, but was, in fact, simply a cover for the realpolitik the Soviet Union utilized to make the Middle East one of its spheres of influence, with the Soviet Union often sidelining Palestinians in favor of keeping allied Arab states within their orbit. Even at the height of Soviet aid to the PLO, the relationship was one of conditional love and, in some ways, borderline cruelty in its pragmatism.

To gain an understanding of Soviet rhetoric concerning Palestine, one must take into account two major tenets of Marxist-Leninist doctrine: the concepts of proletarian internationalism and self-determination of nations. Proletarian internationalism is the notion that, as Marx and Engels said in the Communist Manifesto, “the working man has no nation” and that the interests of the international proletariat take priority of the interests of one’s own nation. At the same time, Marxism-Leninism espouses that all nations have a right to determine their own destiny without fear of intervention from imperial and colonial powers. From its birth, the Soviet Union — at least ostensibly — believed that it, as a nation, had a duty to stand in solidarity with the anti-colonial and national liberation struggles of the Third World.

According to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s official policy, Zionism was “the most reactionary variety of Jewish bourgeois nationalism” and “distracts Jews from class struggle because it treats Jewish workers and bourgeoisie as both having the same interests.”1 While Jews were an officially protected national minority with their own small autonomous oblast in the Russian Far East and antisemitism was heavily disdained in Soviet discourse, Jews were not seen as a coherent nation-state with distinct ties to a particular region of the world. As such, the idea of a Jewish homeland within Palestine was, in a Soviet Marxist framework, completely unacceptable and could only act as an imperialist project for capitalist powers against the colonized Arab peoples. Soviet Jewish organizations, following the party line, were resolute in their opposition to Jewish migration to Palestine.