Taylor B continues the debate on political subjectivity, revolutionary strategy and the party-form, responding to Donald Parkinson’s Without a Party, We Have Nothing.

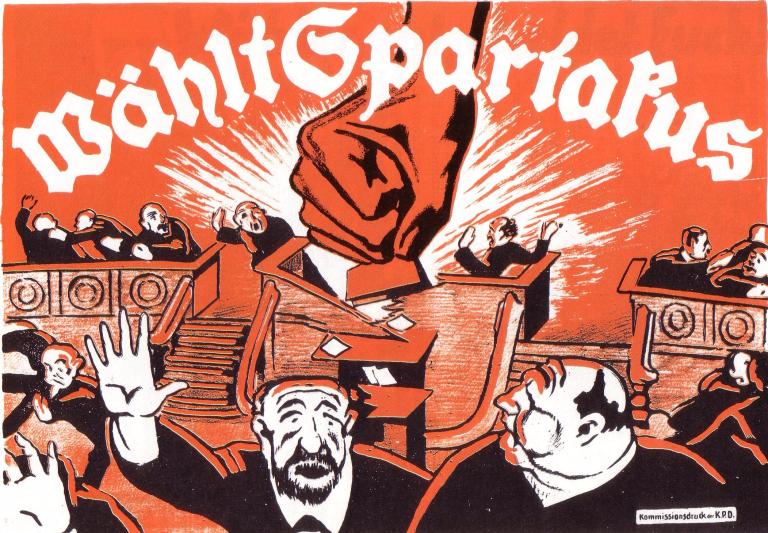

When replying to criticism, I think it is best to put all of one’s cards on the table. In August of last year, millions were in the streets and two Marxist caucuses in DSA were discussing how to advance the emancipatory struggle. In my view, the problem with this discussion was the way in which something called a “worker’s party” was posed as an obvious answer to the “movementism” around the world that seems incapable of destroying the current order that can be broadly characterized by vicious capitalist exploitation, ecological destruction, and mass depoliticization.

Far from this discussion producing any concrete proposal for a party, the most insightful contribution seemed to come from one Red Star comrade who expressed caution in approaching the party: that we should not confuse electoral proceduralism for how to organize in a way that helps bring working class people into confrontation with the capitalist class. Rather than focus on what the party should look like in the abstract, we should organize the base of the worker’s party and promote revolutionary political education. Out of this organizing, an actual party strategy would emerge.1

I could not help but ask questions that had not been posed. If the most sensible way to go about building a party is to break with liberal political conceptions and organize and educate others to build a form of organization that we cannot define in advance, then why insist on the idea for a party at all? When millions are pouring into the streets to protest police violence and defend Black lives, is the notion of a “worker’s” party–a term that seems completely foreign to what seems to have been the largest popular mobilization in history–adequate to the moment? Is what seems to be an orthodox Marxist position on the centrality of the party to the communist movement actually an obstacle to a clear assessment of our moment? Why is it that a real movement against the present state of things always seems to be located in the future? And why does insisting on the party, even when it seems to raise many more questions than answers, automatically appear as a concrete answer to the “movementism” that we all agree must be overcome?

So I wrote an essay that tried to grapple with some of these questions.2 I argued against imposing historical organizational forms on present movements, but more importantly, I attempted to think about politics in a way that could explain the complexity of the current movements by evaluating them on their own terms. This led to some adventurous and controversial statements: that in addition to the party-form creating problems for emancipatory movements, the resurgent “socialist” movement seems to be dominated by those who have no interest in abolishing the capitalist mode of production; that certain elements of a “spontaneous” anti-racist movement seem to have a better instinct for opposing the police and the state than those who are interested in Lenin. Ultimately, I suggested that the radical elements of these movements need to find ways to organize together: I pointed to an example of the Juneteenth demonstration in Oakland that was organized by two DSA chapters and the ILWU that seemed to show these movements already doing so. And I posed more questions to suggest more concrete organizing directions that we could take up going forward.

While I was able to have some helpful and clarifying discussions with comrades inside and outside of DSA–some seem to feel that I have not made a sufficient, concrete proposal for how to advance our movement without reference to the party–Donald Parkinson has so far presented the most impassioned criticisms.3 As he writes at the end of his reply: “One thing is for sure – without a party, we have nothing. Because without a party, there is no ‘we’.”

I think we must point out the contradiction in this line that makes it impossible for it to be a clear prescription. I do not think this is a simple error on Parkinson’s part, but a constitutive contradiction that is consistent with the current party discourse. In order to say that “we” have no “we,” Parkinson presupposes a “we.” In other words, to produce a collective subject, there must be a foundational subject that Parkinson does not, and would seem he cannot, account for.

Let’s read Parkinson’s claim more closely. I believe we are caught between two ways of interpreting it. First, taking this statement at its word, we are left with a claim that reduces all of the real organization of “assemblies, affinity groups, and even new nonprofits as initiatives from activists,” along with organizations like Cosmonaut, Red Star, and the whole of DSA, to the situation of powerless, atomized individuals. The lack of a party formed through an articulated common program puts us in a kind of solipsism.

Second, if we strip away the rhetoric, we get a claim that without a party, there is no emancipatory subject. In other words, there is no collective agent that is capable of opposing and overturning the existing society. While this second interpretation does not reduce existing organizations to atomized individuals, it deems it insufficient for emancipatory politics. The various existing groups and organizations fail to constitute a real opposition to the existing order because–and this is where Parkinson advances a very particular notion of the party based on a particular reading of Marx, Katusky, and Lenin–only a party with a common, articulated program has that power. Thus, for Parkinson, the party is an invariant model of politics, rather than a historical one. Short of this particular version of the party that Parkinson advocates, all our various collective efforts amount to nothing.4

I think the second interpretation is the more productive starting point, though I find it difficult to completely ignore the first. I see both agreement and disagreement with Parkinson. We both seem to agree that the construction of a political subject – which is composed of individual militants and yet goes beyond them – is a requirement for emancipatory politics. We both seem to agree that communism is an emancipatory politics and that any politics that falls short of communism will always be inadequate. While Parkinson has not stated this himself, I believe we both agree that there is no universal organized referent for emancipatory politics currently in existence. The question, as always, is what must be done about this.

While Parkinson seems to have aligned himself with Red Star against my position, I do not think Parkinson’s position on the party is necessarily one that Red Star and Emerge would automatically agree with. Why? Because while Red Star and Emerge were having an exploratory conversation, Parkinson seems to already have a set idea of the party being a “state within a state,” etc. I think this strengthens my argument that the party is a term that creates more problems than it solves: without a clear formulation, the party appears as an empty signifier. With a clear, articulated formulation, the party may produce more fragmentation than consolidation. This last point seems to be supported by the fact that an endless number of small groups of militants have not only proclaimed the need for, but also formed parties, and we have moved no closer to emancipation.

This brings us to the disagreement between Parkinson and myself. Parkinson believes the problem of the subject–the lack of a collective organization with the capacity to oppose and overturn the existing society–is resolved solely through the party-form. Meanwhile, I have argued that the party-form is an obstacle to the formation of the subject in our current moment. My position is ultimately untenable. Why? Because this position cannot effectively respond to all the different things people mean when talking about the party.5 So to reformulate my position, I reject Parkinson’s concept of the party as an invariant model of politics. I reject other suggestions that the Soviet or Chinese party-states are emancipatory models that we must reproduce or emulate. To those engaging in exploratory discussions of the party, I would simply question what utility a term like ‘the party’ has if you do not have a fixed idea in mind for what you are building. Doesn’t invoking the party and attempting to take inspiration from past organizations like CPUSA simply invite confusion that we then have to continually caution against, as one Red Star comrade pointed out? Doesn’t the party end up being a future idea for overturning capitalist society, rather than a concrete step in the current moment?

If we know there is all sorts of historical baggage that comes with discussing the party, is it actually controversial to try and think of an alternative to theorizing politics and its organization? It is certainly true that if something isn’t broken, you shouldn’t fix it. But isn’t it clear that something is wrong with the party as a concept, since, despite all of our agreement that we need a revolutionary organization of workers to overthrow the few who would kill us before ever allowing us to decide for ourselves how we should live, that there is no revolutionary party or masses anywhere to be found? And shouldn’t we have an answer to this question that does not depend on a few intellectuals making claims about the development of working people’s consciousness?

Now I will attempt to clarify certain aspects of my position, and also advance some new arguments based on the discussions around my original article. I will respond to Parkinson’s alleged refutation of Sylvain Lazarus, a theorist whose dense but crucial insights should be more widely read and formed a fundamental element of my argument. Finally, I will argue the recent emergence of the Partisan project, a joint publication between San Francisco’s Red Star, NYC’s Emerge, Portland’s Red Caucus, and the Communist Caucus, should be seen as an extremely encouraging step toward the formation of a consolidated Marxist bloc with DSA that can serve as an important site of discussion, study, and experimentation to advance the emancipatory struggle of communism.

Beginnings

According to Parkinson’s summary of my argument in the second and third paragraphs of his response, one of my fundamental claims is that the DSA and the George Floyd uprising are evidence that politics has been “born.” I believe this point indicates a certain misunderstanding: I did not use the terms “birth” or “born” a single time in my “Beginnings” piece. Meanwhile, the term I used 23 times if we include the very first word of my title–beginnings–does not occur at all in Parkinson’s response. Even the less specialized term “beginning”–which combined with “beginnings” occurs 48 times in my essay does not appear at all in Parkinson’s response.

I assume the swapping of these terms is not in reference to something I am unaware of that is important to Parkinsons’ argument, such as a particular dispute in Comintern history, a passage from Pannekoek’s diary, etc. I assume that if Parkinson found my notion of “beginnings” unhelpful or wrong, then he would have demonstrated this through a critique of the concept. But that did not happen. Instead, we have two occurrences of the phrase “birth of politics” in consecutive paragraphs in Parkinson’s reply. We have the claims that I was “heralding a new creative process that will break from all the old muck of the past and create new forms of organization” and insisting that we “declare our fidelity to the spontaneous energies of the event, to see where it goes and what it creates rather than trying to impose our own ideas upon it.”

My point was just the opposite. As someone who is a member of DSA and participated in demonstrations, I attempted to combat idealism and pose questions from within these movements to pursue an emancipatory politics. If this was not apparent to Parkinson, I believe it is because he produces a binary of tailing spontaneity and applying a pre-existing model. This binary suggests that Parkinson, despite his insistence that Marxists should join DSA and sympathy with combatting racist police violence, does not necessarily see himself as part of these movements. Thus, his criticism comes from the outside, and so must my intervention. But this is not my position in regard to these movements, nor am I thinking from within the same binary. I am instead proposing that there is a need for organization and prescription that does not occur “spontaneously,” but also does not consist in the application of a pre-existing model. I am suggesting that members of DSA and those who took to the streets must take it upon ourselves to organize in a better way to oppose the existing, global capitalist order.

I called Occupy, Ferguson, DSA’s growth by way of the Sanders’ campaigns, and the George Floyd uprising “beginnings” because these are real formations that break the pattern of “depoliticized atomization,” to use Salar Mohandesi’s phrase, yet have not produced a political sequence.6 They are not nothing, but they fall short of politics. In contrast, the metaphor of birth and whatever its variations – stillborn, miscarraige, premature, etc. – has entirely different connotations. This gendered and strangely graphic kind of metaphoric language does not grasp the dynamism and lack of definitive origins of the formations I discussed. Even when I claimed that Sanders was in part responsible for setting off a beginning, I tried to show that what was key was not Sanders, but all the thinking that emerged in response to Sanders that disrupted depoliticized atomization.

The basis of my intervention was to say that if these beginnings are to produce political subjectivity, then they must overcome the internal and external forces that seek to neutralize them. I attempted to assess the real conditions of these movements–the balance of emancipatory potential and real neutralizing forces within and outside them–precisely to identify lines that we must fight and organize along so that effective ideas and practices can be produced from within, and thus transform, these formations. That is why I have criticized liberals who say we need to reform the police and run progressive politicians, along with the socialists who reduce riots to emotional outbursts and sometimes fall into a kind of idealist thinking that says we just have to do what the Bolsheviks did. If I did not distance myself from ultra-left positions that say sabotaging trains and looting Targets is the path to emancipation, it is only because I do not take these positions seriously and see very few people advancing them.

The language of beginnings, then, is distinct and fundamental to my approach. By suggesting that the DSA and the uprisings are beginnings, I intended to show that real breaks occurred in the thought of people. How else do we account for people suddenly going from a state of atomized depoliticization to spending an inordinate amount of time on Zoom calls discussing bylaws, or braving crowded streets in a pandemic to demand the end to police killings? Thus, a beginning must break with the neutralizing order. But on its own, this break is not sufficient to constitute an emancipatory sequence due to complex and varied forces of neutralization that maintain the current order. In other words, a foothold is necessary to free climb a mountain; but a foothold does not eliminate the problem of gravity.

So in the schema I produced in the “Beginnings” article, there are two breaks. There is the break from neutralization to beginnings, and the break from beginnings to politics. Since politics is rare and sequential, a new subjective invention that begins and ends, then my claim is that beginnings must be common and chaotic. Beginnings spark, die out, and spark again. Beginnings fundamentally have something to do with the ever-present potential for politics that occurs in the thought of people who are exploited and oppressed that sometimes leads them to organize themselves with others to fight those who dominate them. Unfortunately, it is the categorical limit of beginnings to almost always fail.

Beginning Again

While it seems true that beginnings can be neutralized in the ways I discussed in my article, it seems unlikely that I can maintain the position that neutralization precedes beginnings. The question of going from nothing to something is ultimately a metaphysical or theological question and does not interest me much. Clearly the world, short of emancipation and parties, is not nothing; I don’t believe anyone is claiming otherwise. But we still must be able to account for what occurs between emancipatory sequences. I have proposed beginnings. But then how do we account for beginnings?

To try and resolve the problem of beginnings, I will introduce an idea that I have derived from one of Alain Badiou’s incomparable diagrams. This is the notion of an ordering regime. The ordering regime is the something that precedes a beginning. And the ordering regime is what exists at the close of an emancipatory sequence. To maintain order, to keep everyone in their given places, it must engage in dynamic processes of neutralization. I think that is sufficient for now.

I believe there are four questions that must be addressed to continue clarifying this debate.

First, why is it necessary to talk about this conceptual dynamic between beginnings and neutralization, which appear to speak generically about politics in terms which aren’t contained in the Marxist canon? Why not just talk about class struggle? It is necessary because political sequences are rare, and they do not always have to do with class struggle. The rarity of emancipatory sequences, the rarity of politics, emerges in subjective thought. It is through an event that is irreducible to the present regime or order, or ordering regime, that the subjective thought of politics has the potential to erupt into thought. Sometimes this produces a sustained emancipatory sequence. Ordering regimes attempt to neutralize this movement; this sometimes forces a major re-ordering. The complicated dynamics of the ruling class, itself the condensation of many bourgeois interests, is one general historical example of an ordering regime. Fundamentally, politics is about people breaking from the places assigned to them by an ordering regime. It is in this sense that we can understand Badiou, when thinking in reference to the situation in 1968, he asks:

What would a political practice that was not willing to keep everyone in their place look like?…What inspired us was the conviction that we had to do away with places. That is what is meant, in the most general sense, by the word ‘communism’: an egalitarian society which, acting under its own impetus, brings down walls and barriers; a polyvalent society, with variable trajectories, both at work and in our lives. But ‘communism’ also means forms of political organization that are not modelled on spatial hierarchies.7

Second, what is emancipatory politics? Emancipatory politics is the name of the rare, subjective thought in the minds of people that prescribes the correct forms of organization to destroy “the places” of a given ordering regime in a movement toward the absolutely free and egalitarian association of all people. The common name for universal emancipatory politics is communism: it is the real movement against the present state of things. We might say that emancipation is not a state of affairs to be realized, but a project without end predicated on subjective thought: it fundamentally has something to do with the power to decide.

Third, why are emancipatory sequences rare? Politics must begin in thought as a relation of real circumstances. I want to be explicit here: I am not talking about thought in idealist terms. I am thinking of thought in the same way Lenin uses theory in his famous statement that without revolutionary theory, there is no revolutionary movement. My point is to detach thought from theory. Theory is essentially a systematized way of thinking. Thought must be fundamental to the existence of theory, though without the supposed guarantees of a particular revolutionary theory. If we understand “emancipation” to have a broader meaning than particular Marxists theories of revolution–with emancipation serving as a common category to think sequences as different as the Hatian Revolution and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution–then “thought” is the broader common category that links Marxist theories with the different but still correct ideas of the Haitian Revolution.

How can we support this claim? We can say that while Marxist theory has been proven correct time and again in guiding emancipatory movements, it is not the only thought to have done so. As I have indicated, thought does not come with the same guarantees as scientific socialism. Nevertheless, correct prescriptions–ideas that are confirmed correct through their material and practical consequences–begins in thought.

This brings us to the point about rarity. Real circumstances are always exceptional: each circumstance consists of an uneven balance of forces that are produced through an accumulation of historical contradictions. The formation of emancipatory politics is rare because it is incredibly difficult to produce the correct thoughts and unique forms of organization that are adequate to contest the present ordering regime in the exceptional, overdetermined moment. In other words, politics must begin in thought but can only be realized through correct prescriptions. In this sense, emancipatory politics both begins in thought and is fundamentally material.

The reason why I have suggested that thought is central to politics is because thought is already something that is always happening in the minds of all people, regardless of their understanding of the world. Thought is a fundamental category of subjectivity and human agency. The question for those of us involved in the struggle for emancipation is which thought, and at which sites, does a lasting subjectivization emerge that can topple the given and exceptional ordering regime? The particular sites of politics–the places where thought occurs–are what must be discovered so we can alter our current forms of organization to produce the rare, emancipatory sequence.

Fourth, if politics is rare, are we to believe that history is a series of disconnected moments with no continuity between them? Is each beginning or emancipatory sequence always forced to start from scratch? I will admit that the question of history is made extremely complicated by the frameworks of Badiou and Lazarus which I have drawn on. But I will also say that history has always been a complicated question in Marxism, already evident in the longstanding debate about Marx’s relation to Hegel, Marx’s letters on Russia, the debate between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks, the question of “stagism,” the debate over the Stalinist “theory of the productive forces,” etc.

Instead of attempting to resolve the problem of history in Marxism, I will address the questions I have posed related to history with reference to an axiom of Marx and Engels: that history always progresses by its bad side. For Althusser, the bad side is the side from which people do not expect history to progress. I understand this to mean that the past does not transmit an accumulation of “lessons” that lead us to a final victory, but an accumulation of contradictions that form the exceptional circumstances of the present moment. This moment is managed by the given ordering regime. And it is also a condition of the real which, through an event, erupts within subjective thought in interiority.

From the framework of emancipatory sequences, what is continuous is the problem of the exceptional present, and thus, new ideas that can prescribe correct practices to overcome it. As Lazarus writes in a forthcoming translation of a 1981 text: “one must continue to find the rupture.”8

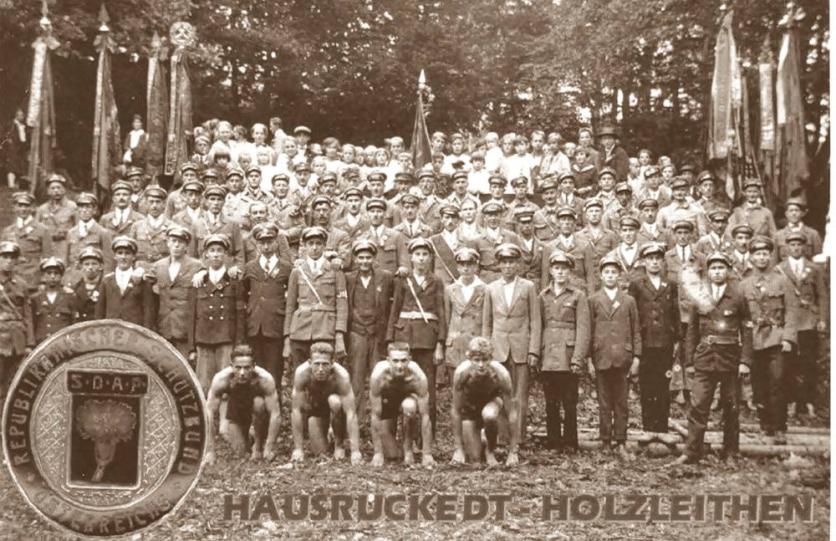

With a more limited understanding of continuity, we might say that different degrees of continuity between emancipatory sequences is possible at times. But greater continuity does not guarantee that solving the problem of the present will be any easier. For example, one might argue, as Parkinson does, that there was a continuity between Marx and Lenin via Kautsky and the SPD. But even with this degree of continuity, it was by no means obvious or guaranteed that Marxism could be adapted to the Russian context. It was the discontinuity and difference–that which was new in Lenin’s thought–that made Lenin’s contributions to Marxism possible and significant. We might go so far as to say that, for Lenin, Marxism itself was one dimension of the problem of the present.

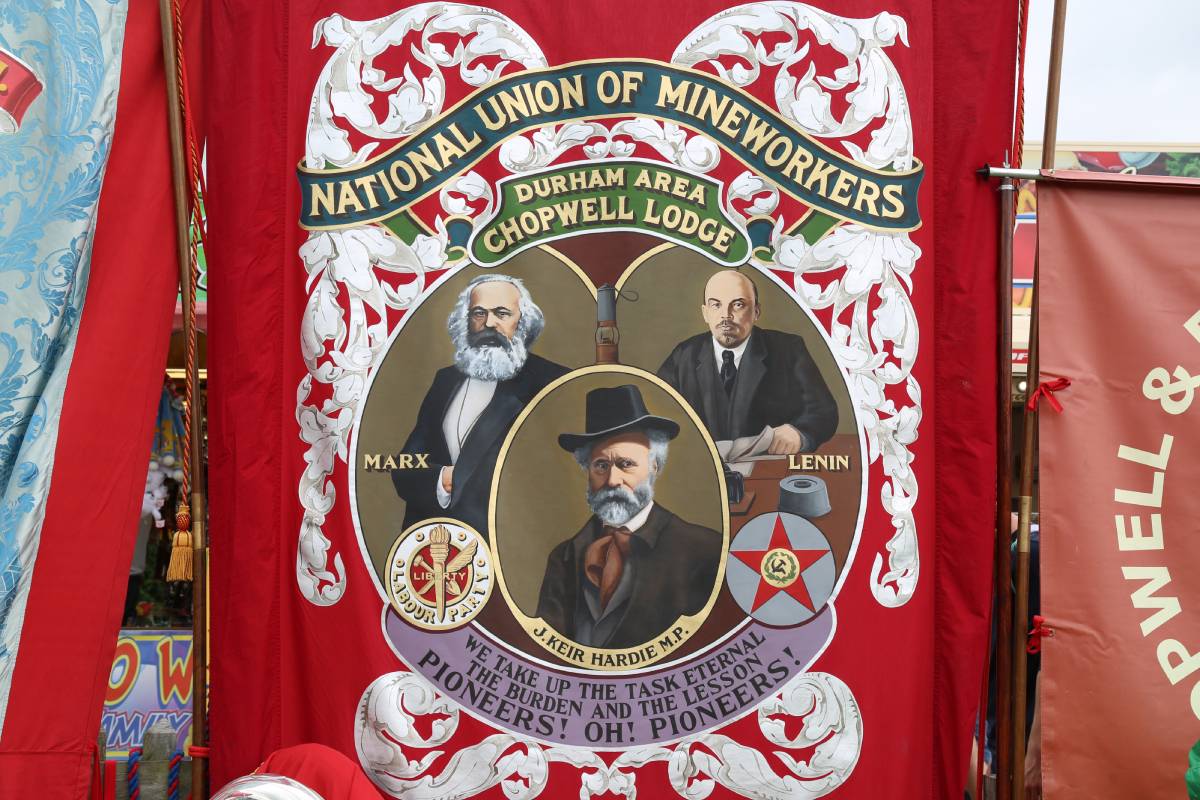

Marx, Lenin, and the Party

Now Parkinson has vigorously contested my usage of Lazarus to argue that Marx and Lenin had differences on the question of the party. I will get to that. But to continue with my discussion of continuity and discontinuity, I must again assert that Lenin’s thought contains new ideas that cannot be found in Marx. We will bracket the question of whether or not Lenin invented these ideas: we will simply compare the ideas of Marx and Lenin. To avoid saying anything controversial, I will reassert the difference between Marx and Lenin with reference to Rossana Rossanda’s 1970 classic, “Class and Party.”

As Rossanda explains, “what separates Marx from Lenin (who, far from filling in Marx’s outlines, oriented himself in a different direction) is that the organization is never considered by Marx as anything but an essentially practical matter, a flexible and changing instrument, an expression of the real subject of the revolution, namely the proletariat.”9

To fully appreciate the difference between Marx and Lenin, we need to focus on Marx for a moment. Marx sees a “direct” relationship between the proletariat and the party of the proletariat. In fact, “the terms are almost interchangeable. For between the class as such and its political being, there is only a practical difference, in the sense that the second is the contingent form of the first.”10

What is the mechanism that produces this organized, “practical difference”? For Rossanda, Marx sees the class struggle with its “material roots in the mechanism of the system itself.” We can refer back to Marx’s famous letter to Weydemyer to support Rossanda’s reading. Interestingly, when reviewing Marx’s letter we immediately see him address the question of originality.

And now as to myself, no credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society or the struggle between them. Long before me bourgeois historians had described the historical development of this class struggle and bourgeois economists, the economic economy of the classes.

First, I think we can immediately see the question of originality is more complicated than Parkinson makes it out to be. Marx plainly states that his discovery is not the historical development of the class struggle, but something more specific. Fortunately, Marx gives us a clear description:

What I did that was new was to prove: (1) that the existence of classes is only bound up with particular historical phases in the development of production (historische Entwicklungsphasen der Production), (2) that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat, (3) that this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society.11

In other words, what was new in Marx’s work was showing how the class struggle does not simply relate to historical development, but “historical phases in the development of production.” This discovery produces a particular emancipatory prescription. As Rossanda rightly says, for Marx, the category of revolution is thus the “process which is intended to transcend the system.” Revolution is “a social activity which creates, over time, the political forms which the class needs and which constitutes its organization–namely the party.” Despite the apparent interchability of the terms “party” and “proletariat,” we see that for Marx “this is only so in the sense that the former is the political form of the latter, and constitutes its transitory mode of being, with the historical imperfections of concrete political institutions; while the proletariat remains the permanent historical subject, rooted in the material conditions of the capitalist system.”12

To return to Lazarus, we should note that Rossanda employs Lenin’s periodization of Marxism as found in his “The Historical Destiny of the Doctrine of Karl Marx” essay. Lazarus, Rossanda, and Lenin all agree that 1848 to 1871 was a specific phase or sequence that centers on Marx’s thought. For Lazarus, this phase is called the “classist mode” of politics, with Marx being its main theorist. We should be clear that Lazarus is using the term “classist” in a particular way. Rather than referring to discrimination based on class, he is referring to the idea that there are historical laws which determine the existence of classes in society and the struggle between them – exactly what Marx said in the letter to Weydemeyer that he had inherited from the bourgeois historians.

For Lazarus, a mode is “the relationship of a politics to its thought.”13 Rather than this mode beginning with the 1848 revolutions as Lenin claims, Lazarus expands this beginning to include the publication of the Communist Manifesto. Again, I believe both Lenin and Lazarus would agree that this period can be characterized as one in which “Marx’s doctrine by no means dominated. It was only one of the very numerous groups or trends of socialism.”14 While Marx’s thought proved to be a subjective, emancipatory thought that, to use Lenin’s words, “gained a complete victory and began to spread” after 1871, Lazarus argues that this is the moment when the sites of Marx’s thought lapsed and the whole classist mode became exhausted. Why? Because the Paris Commune revealed the limits of the thesis of Marx’s merger of “the prescriptive and the descriptive,” the merger of “history and politics” that takes the name “historical consciousness.”15 Nevertheless, it is clear that Marxism did continue to grow and spread as Lenin claimed.

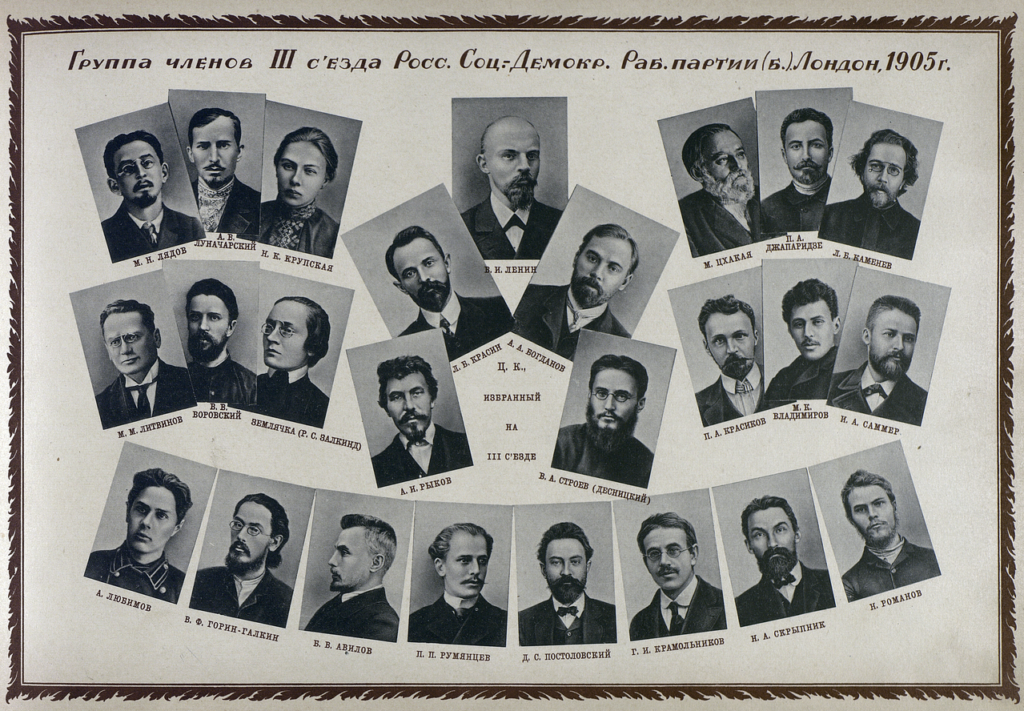

Lenin and Lazarus’s periodization diverges in an interesting way. For Lenin, there is a second period from 1872-1904 that is characterized by the “absence of revolutions” and “the theoretical victory of Marxism” that “compelled its enemies to disguise themselves as Marxists. Liberalism, rotten within, tried to revive itself in the form of socialist opportunism.”16 Then there is a third period from 1905 to Lenin’s textual present of 1913 when “a new source of great world storms opened up in Asia. The Russian revolution was followed by revolutions in Turkey, Persia and China. It is in this era of storms and their ‘repercussions’ in Europe that we are now living.”17

I think it is striking that the dates of Lenin and Lazarus’ periodizations align so closely. While Lenin points to the Russian Revolution of 1905 as a second revolutionary era in Marxism, Lazarus argues that the Bolshevik mode begins in 1902 with Lenin’s publication of What Is to Be Done? (WITBD). Again, Parkinson has challenged this point and I will take it up later.

The point I want to make is that the end of the “classist mode,” or first period of Marxism, seems to contain an insight into Marxism in general. Until 1871, Marxism was not a victorious doctrine: it was the thought of Marx. Famously, Marx never claimed to be a Marxist and it is a somewhat common view to see Engels as the real creator of Marxism. But then, as we know, Engels has been criticized heavily for some of his formulations. This is to say that the first Marxist is by no means a prophet, but begins a critical discussion of Marx’s work. In this sense, it would seem that it is impossible to view Marxism as a singular, cohesive set of ideas: Marxism is always contested. I would suggest that the “doctrine of Karl Marx” that became victorious is not so much Marxism, but the emergence of multiple Marxist tendencies: of Marxisms.

This would seem to be reflected in Lenin’s second and third periods. After 1871 we can see two tendencies develop, though not necessarily in a clean fork from Marx’s work. On the one hand, there was the mechanical tendency that came to be advanced by Kautsky and Bernstein in the Social Democratic Party of Germany. In this sense, we see that while Luxemburg was correct in her famous criticism of Bernstein, this mechanical tendency did have its roots in a particular understanding of politics that is unique to Marx: the merger of history and the politics. The problem ultimately was that Bernstein had failed to see that the realization of communism as a result of historical phases in the development of production had already been exhausted. On the other hand, due to the “backward” Russian situation, Lenin would be forced to find another way.

To put things very simply, Lenin’s other way would take the name Leninism. And Leninism would correctly oppose other non-Marxist and Marxist tendencies, with the proof of its correctness culminating in October 1917. But the Lenin of 1913 could not have known he was to become a great thinker of emancipation or that his 1902 intervention–WITBD–could be seen as the basis of a distinct mode of politics. Yet it is telling that Lenin dates 1905 as a key moment for the second revolutionary period in Marxism with reference to the 1905 “dress rehearsal.” While the 1905 revolution was not successful, it produced a new, revolutionary form of organization: the soviet. Combined with the party, the soviet put the question of revolution back on the table: a new emancipatory sequence had begun.

Let’s return to Marx so we can see more clearly what’s new in Lenin. According to Lazarus, a key thesis of the classist mode is: “where there are proletarians, there are Communists.” As Rossanda shows, for Marx, “the proletariat in struggle does not produce an institution distinct from its immediate being”: if “one does not find a theory of the party in Marx, the reason is that, in his theory of revolution, there is neither need nor room for it.”18 Thus, from Marx to Lenin we see a recasting of the dialectic “in which the subject is the proletariat and the object society produced by the relations of capitalist production, thus moves towards a dialectic between class and vanguard, in which the former has the capacity of an ‘objective quantity,’ while the latter, the party, being the subject, is the locus of ‘revolutionary initiative.’”19 I would like to emphasize what is at stake in this shift: a fundamentally different conception of the emancipatory subject.

Why was Lenin’s break with Marx necessary? It is the same reason that for Lenin, Marxism was one dimension of the problem of the present. “Lenin’s horizon was delimited by two major facts: first of all, capitalism has entered in the imperialist phase, and its crisis reveals itself more complex than had been foreseen.”20 Beyond this, “Lenin, throughout his life, had to face the growing resistance of the system, and a capacity for action of the working class much inferior from 1848 to the Paris Commune.”21 Ultimately, “the capitalist and imperialism system was defeated in areas which, according to the Marxian schema, were not ‘ripe’ for communism.”22 In other words, for Lenin:

the confrontation must be prepared: the more society lacks ‘maturity,’ the more important it is that a vanguard should provoke the telescoping of objective conditions with the intolerability of exploitation and a revolutionary explosion, by giving the exploited and the oppressed the consciousness of their real condition, by wrenching them out of ignorance and resignation, by indicating to them a method, a strategy and the possibility or revolt–by making them revolutionaries.23

It would seem Rossanda is once again in agreement with Lazarus. For Lazarus, “the basis of Lenin’s thinking and of the Bolshevik mode of politics is the following statement: Proletarian politics is subject to condition…that it is subject to condition indicates that politics is expressive neither of social conditions nor…of history as Marx conceived of it.”24 Lazarus develops this point further, noting that “Lenin does not go so far as to abandon the connection between class and history but he makes it conditional on consciousness.”25 Lenin’s break nonetheless leads us to an inversion of a classically Marxian understanding of antagonism:

one cannot argue that it is antagonism that constitutes consciousness–it appears instead to be one of its propositions, the end product of a process subject to condition. Therefore, it is not antagonism that produces consciousness but consciousness that declares it…Consciousness is not so much a historical space as a political and prescriptive space.26

Now that we have seen what is new in Lenin, we are in a position to conclude this section with a turn toward our own exceptional present with the question of continuity and discontinuity in mind. To put what I have said in a slightly different way: since the circumstances of the present are always exceptional, the question of emancipation must always begin with a new, unbalanced equation. A limited notion of continuity may supply us with some notion of a constant, but it is what’s discontinuous, the formation of the new answer to the new equation, that we must always solve ourselves.

Let’s try to push this mathematical metaphor further. We might say beginnings are what occur on scratch paper until a solution is produced; it is the arrival at the answer that transforms what was a messy scrap into the site of an ingenious breakthrough. It is that site of the breakthrough that has the potential to support the lasting formation of the subject, which is composed by militants it at the same time exceeds. There are no guarantees, only a wager that can be made in correspondence with the upsurge of the masses, or to use Lenin’s term, stikhiinost.27

On what basis can we claim this site is necessarily the party? Even if we could say with certainty that the categories and sites of historical modes of politics will occur in the form of something called a party, then what are we left with if not another undefined variable? The matter is much more difficult than simply having an undefined variable, since this is precisely what we started with. Abstract reference to the party produces a figure that only gives the appearance of definition: what we are left with is a shadow cast on the whole situation that we confuse with the real.

To put it another way: at best, the party discussion amounts to a confusing and overwrought insistence on organizing to produce an emancipatory subject and the sites that give it consistency. But it does not say any more than this. In this scenario, insistence on the party does not give us any clues about which subjective thoughts, at which particular sites, could produce correct prescriptions to advance the emancipatory struggle in our exceptional moment. At its worst, the party discussion reduces the question of subjectivization to ideal organizational structures, procedures, and administration to build “states within states” and other unappealing creations. This amounts to a schematic application of blueprints from the past and, unsurprisingly, consistently fails to generate any support beyond the dozen people who were inspired by a particular episode in the history of the international communist movement.

Beyond the best and worst scenarios, I think there are additional dangers. Since our current socialist movement has only the faintest understanding of what capitalism is and that it must be abolished, mechanical calls for things like “democratic centralism” could very well become the means to reelecting progressive Democrats to save and manage capitalism in a crumbling two-party system. Why? Because if the subjective, emancipatory character is not a question we are concerned with–if politics is not in command–then the vicious existing order of exploitation and exclusion stands and depoliticized proceduralism reigns.

The Method of Saturation

We now have to make an abrupt turn to Sylvain Lazarus’s notion of “modes of politics.” Parkinson believes Lars Lih’s work on Lenin refutes Lazarus’s periodization of emancipatory sequences. Parkinson makes two claims: first, that Lazarus’s method provides no explanatory value because “the only thing that Lazarus’s narrative explains is why he thinks we need to abandon all the past concepts of Marxist politics and come up with something completely novel.” And second, that “the narrative Lazarus paints is simply not true. Lenin was not breaking with the political practice or conceptions of Marx and Engels in What Is To Be Done? and wasn’t making any kind of original argument.”

Let’s begin with the first claim: that Lazarus is simply projecting his pre-formed conclusions back onto history to discard all Marxist categories, and therefore his analysis has no value. As I have said, it was my intention to provoke a discussion by turning to Lazarus; I am glad to have the opportunity to discuss him further. While I do have reservations about his work, I think there is tremendous value in thinking through it.

It is telling that in Parkinson’s 336 word summary of Lazarus’s argument as found in “Lenin and the Party, 1902–November 1917,” the name of Lazarus’s method–saturation–is nowhere to be found. I believe Parkinson’s frustration with and suspicion of Lazarus’s analysis is symptomatic of the fact that he does not engage at all with Lazarus’s method. This is an obvious problem if you are going to refute an argument, but by no means do I think Parkinson is to blame. To be fair, the word “saturation” appears only once in Lazarus’s “Lenin and the Party” essay to which Parkinson refers. Had Parkinson read Lazarus’s “Can Politics be Thought in Interiority?,” often considered an introductory text, he may have run into similar troubles: the term only appears once in there too around the middle.28 Nevertheless, I am sure Parkinson pored over Lazarus’s “Lenin and the Party” text looking for its weakness and revised his summary of Lazarus’s argument extensively. Clearly, we need more opportunities for greater collective study to work through complicated issues, and in this regard Parkinson’s efforts are salutary. However, for efforts to be fruitful, they have to go beyond rejoinders to isolated points and actually engage with the underlying questions and categories of the text.

It is true that in his text on Lenin Lazarus dismisses “the category of revolution.” For Lazarus, “this dismissal is a complex business, for the closure by itself does not break historicism.”29 This point raises more questions than answers. What does Lazarus mean by “historicism”? Where is Lazarus’s argument ultimately taking us? Are we going to be forced to accept Lazarus’s dismissal of revolution?

Let’s work backward, taking the last question first. I do not think dismissing the category of revolution is necessary. It is sufficient to reject a static conception of revolution, and instead evaluate the concept in relation to the various circumstances in which it appears. Since Lazarus is attempting to make a very particular point about “the category of revolution,” I do not think engaging in a discussion of his method equates to full endorsement. In my opinion, the dismissal of the category of revolution is a highly controversial, though nonetheless interesting, idea to think through.

To give some idea of where Lazarus’s argument takes us, Lazarus will reject a purist framework that says we should reject the Bolshevik mode because it was intrinsically authoritarian and doomed to failure. For Lazarus:

the method of saturation consists in the re-examination, from within a closed mode, of the exact nature of protocols and processes of subjectivization that it proposed. We are then in a better position to identify what the statements of subjectivization were and the ever singular reason for their precariousness. The thesis of the cessation of a subjective category and that of the precariousness of politics (which goes hand in hand with the rarity of politics) are not supplanted by a thesis with regard to failure and a lack of subjectivization.30

Perhaps this passage gives us a sense of what Lazarus means by “closure.” Nevertheless, we can see clearly that the method of saturation has something to do with a “re-examination” to better understand the protocols, processes, prescriptions, and statements of subjectivization that compose a mode of politics. We see clearly that subjective categories are “precarious,” and that this precarity has something to do with its rarity. We see that the cessation of a subjective category does not authorize one to make the accusation of failure.

We must ask what Lazarus means by “historicism.” After a discussion of the Bolshevik mode–which I gave an account of in my “Beginnings” piece–we are left with Lazarus’s claim that “the lapsing of the party form, in its political efficacy, was thus complete after November 1917,” and “from this moment on we enter a historicist problematic of politics in which the key word becomes revolution.” So we see that “historicism” is a problematic, or theoretical framework, of politics that comes after the closure of the Bolshevik mode. The Bolshevik mode was a real emancipatory sequence whose sites were the party and the soviet. The party “lapsed,” which is to say that it was no longer a site of emancipatory politics, after its fusion with the state in November 1917, thus subordinating the soviets to its directions.31 Following this lapse, the term “revolution” is symptomatic of, or indicates, the “historicist problematic of politics.”

We have two questions now: why is the term revolution symptomatic of a historicist problematic of politics? And still, what is the historicist problematic of politics?

We have to pay close attention to what Lazarus means by revolution. “The term revolution is not a generic term denoting an insurrection against the established order, or a change in the structures of a state—and a state of things. It is on the contrary a singular term.” It is a “singular noun” that “constitutes the central category of acting consciousness” that belongs to what Lazarus calls the “revolutionary mode, the political sequence of the French Revolution.”32

So we see the problem clearly. For Lazarus, “revolution” is a singular term that belongs to a particular sequence that occurred from 1792-94 that had its own main theorist (Saint-Just) and sites of politics (the Jacobin Convention, the sans culottes, and the revolutionary army).33

For Lazarus, the issue with retaining the term “revolution” is that it was exhausted in 1794 with the closure of the French Revolution, what he calls the “revolutionary” mode of politics. In order to understand the specificity of this emancipatory sequence and how it came to an end, he interprets “revolution” as a category that is located within it and cannot simply be generalized to any political situation. What is at stake here is that a “historicist problematic of politics” does not conceive of singular conceptions of subjectivity as a relation of the real circumstances in which they emerge. If “revolution” is understood as a singular category of political thinking, then it is because the term has to do with the moment in which revolution bears “political capacity.”34 Otherwise, the term has been “captured” at its most fundamental level by the “historicist” notion that “marks out the state as the sole and essential issue at stake in politics.”35 In other words, if the category of revolution is captured by historicism, then revolution cannot pertain to a subjective decision that is thought in thought. The category of revolution, removed from singular context, thus becomes a category of a de-subjectivized statism. In this case, the category of revolution is deprived of its emancipatory power.

Let’s try to put all this more simply. If we agree that emancipation is our goal, we have to then confront the question of the emancipatory political subject – that is, what allows us to identify a politics that cannot be reduced to the objective conditions of the existing reality. We have to engage in the difficult task of identifying particular subjective occurrences as a thought of politics that relates to its objective circumstances but can also go beyond them and put the ordering regime into question. Otherwise, our thinking is dominated by “circulating” political ideas – that is, categories that were formed within specific situations which are generalized and circulated to entirely different situations. These circulating notions prevent us from understanding how categories specific to a historical mode of politics have been exhausted and are no longer appropriate to the current moment. In effect, we remain “captured” by the present state of things and unable to advance the subjective thoughts of our circumstances that are required to struggle for universal emancipation.

Now that we have discussed and defined the “historicist problematic of politics,” I believe we are in a position to see why Parkinson’s claim that Lazarus’s method contains no value and that it seeks to do away with all Marxist categories indicates a serious misunderstanding. While Lazarus may be interpreted as “breaking” with Marxism, the larger point is that he breaks with all other formalized disciplines, including social science and history, to construct his theory of politics. This move is interesting because even though he speaks of “dismissal,” he by no means suggests we discard Marx, Lenin, or Mao. His argument is that disciplines like history and social science have already done this since becoming captured by the historicist problematic. In other words, Lazarus argues that social science and history have significantly contributed to the “destitution and criminalization of the ‘revolutions’ of the twentieth century.” This criminalization of the revolutionary thought and practice of Marx, Lenin, and Mao becomes the basis for the “contemporary parliamentary” regime. This regime consists of “competitive capitalism, commodities, and money presented as voluntary choices of our freedom,” leaving us with “the collapse of thought, reduced to microeconomics and the philosophy of John Rawls, or rendered coextensive with the political philosophy of the rights of man in a senile appropriation of Kant.”36 As Lazarus further explains:

The fall of the Soviet Union and socialism has fully confirmed the good historicist conscience of parliamentarianism in its rightful place and considerably reinforced its arrogance, its violence, and its legitimacy, allowing it to treat any reservation and criticism, worse still any other project, as crazy and criminal.37

So we see that for Lazarus, the dismissal of revolution is not an attack on Marxism or emancipation. Rather, the act of dismissal is the basis for Lazarus’ radical critique of the disciplines of social science and history that have foreclosed on the possibility of organizing human life in any way beyond the depravity of our existing society. In other words, Lazarus does not proclaim the end of history or revolution: his point is that social science and history have already done this. Rather than argue for a renewal of social science or history, he attempts to overturn them completely to think about the possibility of emancipatory politics.

Let’s return to the passage that I began with about the dismissal of the category of revolution, this time in full:

This dismissal is a complex business, for the closure by itself does not break historicism. What is involved is in no way closing a previous stage and moving on to the following one (which is the case with historicism), but rather maintaining that any closure requires the re-examination of the era whose closure is to be pronounced. This is what I call saturation, a method that traces the subjective spaces of the categories of the sequence to be closed.38

Here we see the lone occurrence of “saturation” in the Lazarus essay that Parkinson focused on. As Lazarus clearly indicates, this word represents his very method, and is clearly fundamental to his analysis in which there are historical modes of politics.

As I have already suggested, saturation is defined as a method that attempts to understand the singular forms of subjectivity: “the exact nature of protocols and processes of subjectivization that is proposed.”39 To “prevent us from turning modes into subjective abstractions,” the subjective category is taken into account with its historical moment, thus giving us the historical modes of politics.40 The historical moment is essentially defined by Lazarus’s “category of historicity” which “renders the question of the state.”41 We see that the “closure” of these sequences, of identifying the moments in which the sites of this subjectivity breaks down, by no means gives us permission to “move on to the following one,” as this “moving on” is precisely what characterizes the historicist problematic which deprives the occurrence of subjectivity its power. In other words, Lazarus rejects a stagism that might put Marx, Lenin, and Mao into a particular kind of order, with one supplanting the next. For Lazarus, historical modes of thought have to be taken in their singularity.

Lazarus’s method of saturation means putting the instances of subjectivity in their correct place to be kept alive as relations of their moment so they can be “re-examined.” Thus, it is the method of saturation that, by way of this re-examining of “subjective spaces,” allows us to identify “the singularity of the politics at work” in a particular sequence. By putting the category of revolution in its correct place in the revolutionary mode and removing “from October the description of revolution,” Lenin and the Bolshevik mode are given back “its originality and its unprecedented political power—that of being the invention of modern politics.”42

So here we see that Lazarus’s method of saturation produces a schema of emancipatory sequences through careful study of singular subjectivity. This includes the re-examination of Marx, Lenin, and Mao within their particular spaces. Clearly, a re-examination of Marx, Lenin, and Mao cannot mean doing away with them. What is interesting to me is how this method opens the door to thinking about emancipatory formations that exist outside the historically contingent boundaries of the communist movement. It is in this sense that I agree very strongly with Mohandesi’s invocation of Althusser: that “it is not a matter of ‘expanding’ the existing politics, but of knowing how to listen to politics where it happens.”43

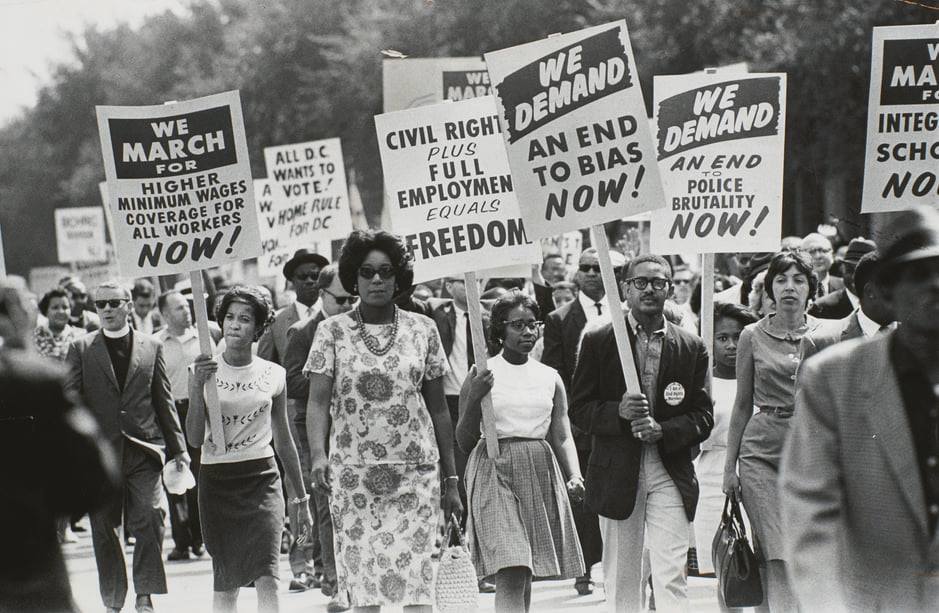

This is why I think Asad Haider is correct to argue that the Civil Rights Movement was an emancipatory sequence.44 As Marxists, I believe we need a theory that can account for events like the Montgomery bus boycott and sequences like the Civil Rights Movement in their own terms. Rather than continue to evaluate the degree of development of people’s consciousness in relation to a particular emancipatory thought, I think we should consider Lazarus’ founding axiom: people think.

Take the Montgomery bus boycott as just one example. Segregation on busses was both a particular form of oppression that was essentially a universal experience for Black people living in Montgomery. While Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat was an event of rupture, she was by no means the first to engage in this act of refusal. What was the result? Roughly 40% of a city boycotted a primary mode of transportation for nine months. Their boycott put significant pressure on municipal revenues. The refusal of public transit disrupted white households to such an extent that white women who were not sympathetic to the boycott would pick up the Black women who worked in their homes and lie to their husbands about doing so. Those with cars participated in the organizing of ride-sharing programs to help the boycotters get around.45 All of this incredible organization happened, yet the notion of a political party is nowhere to be found. But there were clearly thought and correct prescriptions. There was clearly something we might call discipline or fidelity, some kind of active principle that drove people to such incredible lengths to oppose the existing society. How do we begin to account for this? We say that people think.

Refuting Refutation

However, even if we bracket the question of method, we have to address an empirical objection. Parkinson goes further than stating that Lazarus’s overall approach has no value. He claims it is categorically false. With reference to Lars Lih’s Lenin Rediscovered, Parkinson maintains that Lenin “wasn’t making any kind of original argument” in WITBD. The text apparently shows “an impressive exercise in aggressive unoriginality.”

Before we can address this criticism, we should first clarify that for Lazarus, WITBD marks the beginning of the Bolshevik mode: it is the beginning of a sequence that runs “from 1902 to October 1917. It was closed by the victory of the insurrection, the creation of the Soviet state, and the renaming of the Bolsheviks as the Communist Party in 1918.”46 By identifying the lapsing of the Bolshevik sites and seeing the successful insurrection as part of the closure of the Bolshevik mode, we separate the contradictions of socialist construction from the singular power of Lenin’s thought. For Lazarus, WITBD is the privileged text because “it bears on politics, its conditions and its thought”: “I think it is absolutely essential to separate radically the texts before the seizure of power from those of the period of the exercise of power.”47 If this is too radical a claim, then we can at least accept that despite the fact that we can find Lenin’s work in his Collected Works, this “by no way means that one can decide a priori that the theses in these thousands of texts are internally homogeneous and coherent. The existence of such a work does not mean continuity, homogeneity, unity.”48 In other words, if we understand the Bolshevik mode as a sequence that is guided by the subjective thought of Lenin over time, then we must see that Lenin’s thought must be heterogeneous. It would follow then that whatever relationship Lenin has to Marx and Kautsky – certainly two people that were significant influences on him – we cannot characterize this influence as static and unchanging.

Now to Parkinson’s criticism on the question of “originality.” If we take Parkinson literally–that Lenin “wasn’t making any kind of original argument”–then we have an extreme position that can be met with what might seem to be a counter-intuitive fact: that repetition is difference.

How can we illustrate this? We can say that even if the totality of Lenin’s political expression had been submitting quotations from the Collected Works of Marx and Engels in the original German to his opponents without any additional commentary–even if Lenin had randomly drawn pages of Marx’s actual manuscripts from a hat and nailed them to the doors of his rivals–this would still be in some sense “original,” though certainly bizarre and likely ineffective. Why? At the most immediate level, because simply selecting quotations from works which were frequently unfinished or abandoned to the “gnawing criticism of the mice,” which responded to changing historical circumstances and constantly went through developments and changes in their theoretical frameworks, would already represent a specific and contentious interpretation, and this interpretation would be an intervention into a scenario which was totally different from the one in which the works were originally written. But it is also because it is impossible to do the same thing twice.49 It is for this reason that we do not refer to the immortal science of Marxism-Marxism. But even if we did, the placement of the second Marxism would still indicate a difference through its repetition. Indeed, the name “Marxism-Leninism” obviously indicates that “Leninism” is something separate from “Marxism,” thus requiring a hyphen to connect them.

To be fair to Parkinson, we might ask what else his statement could mean beyond a literal interpretation. While I have already shown that Parkinson has neglected to engage with the questions that Lazarus’s method sets out to address, I believe we can read Parkinson’s statements symptomatically to understand what seems to be at stake. I recognize that to this point I have used the term “symptomatic” a few times and should clarify what I mean in the current context. Here I am referring to Althusser’s method of reading that “divulges the undivulged event in the text.”50 Thus, I will attempt to analyze what is happening beneath the text.

Let’s take this statement from Parkinson for example: “What Lazarus is doing is projecting a radical break into history so as to justify that another radical break is necessary.” It would seem Parkinson has been forced into a situation where he must deny discontinuity and difference between Marx and Lenin. This seems to be confirmed by the fact that while the term “continuity” appears five times in his reply, the term “discontinuity” does not appear at all. Instead, we get five uses of the term “novelty.” What is particularly interesting about Parkinson’s usage of “novelty” is that while it is used once to mean the opposite of continuity (his assertion that history is a “flux of novelty and continuity”), novelty is primarily used to accuse Lazarus, and my usage of him, as falling into the fallacy of an “appeal to novelty.” Beyond the suppression of the term discontinuity, the term “difference” does not appear at all in Parkinson’s piece and the term “different” appears once. It is worth noting that Parkinson’s essay is 4,393 words long.

So we see that a symptomatic reading shows that discontinuity and difference is suppressed in Parkinson’s text. Our symptomatic reading of Parkinson’s thesis that Lenin “wasn’t making any kind of original argument” in WITBD produces another tension. We might express this additional tension in the form of a question: to what degree can one person’s thought be continuous with another’s through the reality of difference – historical and geographical difference, and even simply the difference between political actors? To answer this question requires locating what is divergent between the two thoughts. In other words, what does one think that the other does not? While it is certainly possible that Lazarus and myself have posed this question in a Saint-Justian register (“In a time of innovation, anything that is not new is pernicious”), I do not think investigating this question is in any way fallacious. Certainly Lazarus’s reading is challenging to those who are set in their commitments. But then I do not know what the point of study and discussion is if we assume we already have the answer.

So let’s put Parkinson’s literal thesis aside and adopt the question that we have constructed from his text about continuity and difference. Rather than simply read Parkinson against himself, we’ll see if we can support Lazarus’s claims with the arguments Parkinson has made to refute him.

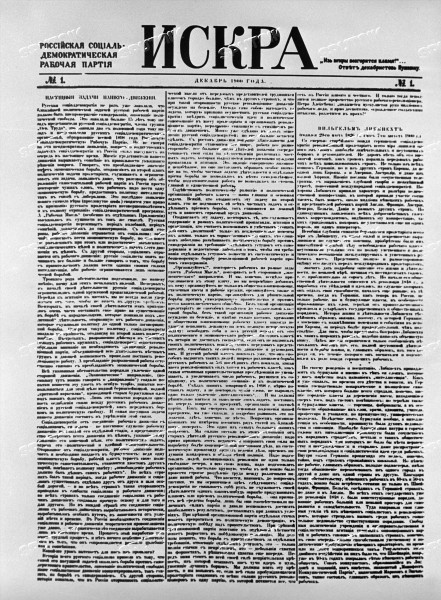

Let’s begin with Lih. While Lih stresses that Lenin’s text is very much in-line with Erfurtian convention, he also clearly states that the fifth and final chapter of WITBD centers on Lenin’s original idea: that a unified Russian party can be constructed through “the nation-wide underground newspaper.” Lest I be accused of misinterpretation I will quote two passages from Lih’s Lenin Rediscovered in their entirety:

The newspaper plan was Lenin’s baby – his own original idea, one that he had laboured long and hard to bring to fruition. His ambitious dream that a nation-wide underground newspaper could galvanise Russian Social Democracy into effective and unified action is here supported with a great deal of ingenuity.51

As Liadov argues, the distinctive dilemma facing Russian Social Democracy was that separate underground organisations that had grown up locally with roots in the local worker milieu had to somehow come together to create central institutions. Lenin’s plan is an ingenious strategy for getting from A to B: from a series of independent local committees to a set of central institutions with enough legitimacy to provide genuine co-ordination (Lenin has this situation in mind when he talks about constructing the Party ‘from all directions’).52

While a national underground newspaper is less exciting than protracted people’s war in the countryside, it nevertheless proved effective and correct. I take this to be a clear indication of Lenin’s singular role in producing the party, which along with the soviet, the organizational form that was “discovered” starting from the 1905 revolution and was absolutely central for Lenin’s conception of politics in 1917, can be understood to be the sites of the Bolshevik mode of politics. By no means was the creation of the all-Russian newspaper an obvious strategy for building the party. This is precisely why Lenin poses the question as the heading of section B of this decisive chapter: “Can a newspaper be a collective organiser?” In Lih’s commentary on this section, he shows that Lenin faced stiff resistance to this idea from Nadezhdin despite their shared goals:

Both Lenin and Nadezhdin want to organise and lead the assault on the autocracy, both of them feel there is vast revolutionary potential in the narod, and both feel that local organisations are the weak links at present. Nadezhdin’s proposed scenario is: the local praktiki organise the people, the narod, for an assault on the autocracy. The activity ‘cultivates [vospitat]’ strong local organisations which are then in a position to unify the Party. But, argues Nedezhdin, an all-Russian newspaper is not much use for the crucial step of organising the narod, because of its inevitable distance from concrete local issues and its ‘writerism.’ In contrast, Lenin’s proposed scenario is: use an all-Russian newspaper to cultivate the local organisations and let these newly prepared leader/guides go out and organise the narod.53

Now that we can see there is an empirically verifiable new idea in WITBD that was essential to the formation of the party, we are brought to yet another decisive point. This point requires that we contest what may seem like a more modest thesis: that there is no meaningful difference between the political thought of Marx and Lenin. This more reasonable thesis is defeated if we seriously consider an argument that Parkinson himself presents. In reference to Marx and Lenin, Parkinson argues that “the break never really happened in the first place. Marx himself fought to form the workers’ party in his own time and struggled within it for programmatic clarity. His own life was an example of the merger formula in practice. Kautsky merely systematized it and Lenin applied it to Russian conditions.”

What is on the surface level an argument for continuity actually relies on identifying discontinuities. If there is no meaningful difference between Marx and Lenin in their political thought, if there is no break, then how could we put Marx, Kautsky, and Lenin into a series of neat successions? Marx lived the merger formula. Kautsky systematized it. Lenin applied it. These are three distinct moments, three different orientations towards the party in entirely different circumstances, and a continuity can only be identified through these differences.

In addition to this point about continuity and difference, we are left with a puzzling question: How can Marx and Lenin have no meaningful difference if Lenin’s politics is inconceivable without Kautsky’s systemization of Marx? Here we see a striking problem for Parkinson: if there is an argument that Lenin did not break with Marx on the question of politics in a decisive way, then this is precisely an argument that a Neo-Kautskyan position would not allow us to make. If Kautsky is a central figure in the development of Marxism, then Lenin must have a meaningful divergence in his thought from Marx since Lenin’s thought is dependent on Kautsky’s systemization of Marx. But if Marx and Lenin do not have a meaningful difference in their thought, this would only be because Kautsky’s thought was irrelevant to Lenin’s development. Thus, a precondition to refuting Lazarus’s claim that there is a break between Marx and Lenin is a rejection of Kautsky. Given that Parkinson and Cosmonaut seem committed to a neo-Erfurtain project, a rejection of Kautsky to show that Marx and Lenin have no meaningful difference in their thought would be a very strange position to take up.

Partisan Conclusions

I would like to close with a concrete proposal. This proposal is the product of reading Lazarus and re-examining Lenin and the Bolshevik mode of politics. I believe this proposal is both guided by Lenin’s subjective practices while also resistant to a mechanical imposition of historical forms of organization.

At a recent CPGB event, I was very heartened to see Parkinson advocate for Marxists to join DSA. I agree with Cosmonaut’s mission statement that we need more lively discussions and study outside of the academy. I believe that DSA is currently the best site for continued discussion, study, and experimentation for the Marxist left in the US. I say this knowing full well the organization’s limitations. While DSA can be a difficult place for a number of reasons, I do not think it can be abandoned.

The recent announcement of the Partisan project, a joint publication between San Francisco’s Red Star, NYC’s Emerge, Portland’s Red Caucus, and the Communist Caucus, is immensely encouraging. I welcome the creation of this publication as a step toward the formation of a consolidated Marxist bloc within DSA through which greater study, discussion, and collaboration within the organization can be pursued and relationships with organizations abroad can be deepend. While the caucus paradigm has been important to organizing and developing different tendencies, I believe the caucuses engaging in the Partisan project are correct to be working together more closely. I suggest this work be taken further so we can overcome the various points of unity within DSA that actually limit the degree to which our forces can be consolidated to combat liberals and wreckers within the organization. It seems to me that the notion of partisanship could be a particularly effective organizing principle in forming such a Marxist bloc. I am thinking here of Gavin Walker’s assertion that “the party means to choose a side, to uphold the concept of antagonism, to emphasize that antagonism cannot be avoided without denying the basic politicality of social life.”54

A diversity of views consolidated around core partisan commitments can be the basis for greater collective study, discussion, and experimentation. The Partisan project seems like the best existing vehicle to drive this consolidation, since it is already a formalized partnership between different tendencies. Crucially, it is still a new project that is presumably still figuring out its direction.

While I am unaffiliated with these caucuses and Partisan, I do want to make a recommendation. I propose that Partisan invite other national and local Marxist caucuses, as well as other Marxists and left publications inside and outside of DSA, including comrades abroad, to join the Partisan project. This could be initiated with scheduling an open meeting on Zoom. This open meeting could be called by the Partisan editorial collective to discuss recent articles that have been published in the Partisan journal and beyond with the goal of meeting regularly to develop and explore collective lines of inquiry and practical experimentation. All of this seems in line with the current language of the Partisan project.55

To be more prescriptive, I would suggest that this project concern itself with subjectivization, rather than “building the party.” In my opinion, the party makes it harder to see the tasks before us; the party locates the forms of organization we need now in the future. Without trying to be exhaustive, I believe we should be less concerned with programs and discipline, and more interested in formulating shared partisan commitments that are capable of supporting a diversity of views while fiercely opposing neutralizing tendencies that seek to collaborate with Democrats and generally maintain mass depoliticization. We should emphasize our current need for the collective study necessary to ask each other better questions, rather than attempt to educate others with inadequate answers. In my opinion, we should give up the notion of “leadership” and instead develop positions of partisanship. This includes combatting the liberal establishment’s call for unity–already the apparent motor of the Biden administration–and insist on division from within the sites where people think.

Extending the Partisan tendency would allow us to construct an organization of militants from within our existing 90k member organization of “official socialist organizers.” To do this without reference to the party would allow us to pursue the collective subjectivization required to construct and advance an emancipatory politics at a distance from the state. While confronting the state will be inevitable, we are currently not in any way equipped to do so. This includes sending our forces “behind enemy lines” to hold elected office or using the publicity of elections to build an organization. Nevermind the fact that an emancipatory politics cannot be reconciled with managing capitalist exploitation and ecological collapse, the prerequisite to utilizing the spectacle of elections and other political institutions, the prerequisite to entering the structure of so-called representative democracy, is a committed core of militants. This is something we simply do not have, but it is something we can create. To suggest otherwise–to say that we do not need a committed core or that one currently exists–is to argue that opportunism is a substitute for politics and that politics must be synonymous with power. Similarly, if our problem is fragmentation, then a growth in membership exacerbates this problem rather than solves it. Ultimately, we must stop attempting to validate our movement through electoral success and paper membership. We must construct our politics on our own terms. It is the fact that these terms cannot be reconciled with the existing order that makes them politics.

As I believe Parkinson said during his discussion with the CPGB, right now we do not need to go to the masses. This is counter-intuitive but it is true. The immediate task is consolidating our forces to determine our commitments so we can give people something new to think about: the thought of politics. And this politics will only be something worth thinking about if it says that everyone has the capacity to think and self-govern. That everyone has the capacity to decide and that we will come together as equals to do what we are constantly denied. We will make a decision.

Advancing the Partisan tendency in the present by consolidating a Marxist bloc seems the best available path to producing an emancipatory movement. It is an insistence on what is partisan, on what divides, that makes possible the collective decision to end capitalist exploitation, ecological armageddon, and mass depoliticization. We cannot wait for liberals to agree with us. We cannot wait for the streets to fill or for a sufficient number of socialists to take office. We cannot wait for exploratory discussions to produce a pre-party organization and for the pre-party organization to produce the party and for the party to develop a revolutionary consciousness in the masses so we can be in the correct position in a revolutionary situation to engage in the art of insurrection. We must organize now. We must consolidate now. We must advance our position from the premises already in existence. This begins with collectively posing the question of the subject in the present, rather than calling for a future party.