Translation and Introduction by Renato Flores.

Tristan Marof was the pseudonym of Bolivian revolutionary Gustavo Adolfo Navarro. Navarro was born in Sucre in 1898. He took an early interest in politics: in 1920 he joined the socialist wing of the broad-tent “Partido Republicano” (PR) that was composed of republicans and socialists who were opposed to the ruling liberals. The PR would come to power following a coup d’etat in the same year of 1920, and as a reward for his services during the coup, Navarro obtained a job as French consul and moved across the ocean. During his stay in France, he would become more radicalized, and produced the two influential oeuvres he is best known for: El Ingenuo Continente and his shorter La Justicia del Inca, to which the fragments translated below pertain. In both of these works, he makes the case for an explicitly American communism, which was based on the traditional indigenous practices of that continent, especially that of the Inca.

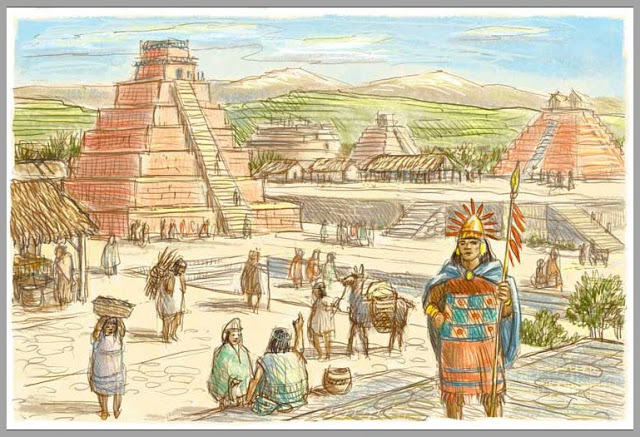

These works lay out a program for a socialist transition that would bypass the capitalist stage, opposing the dominant conception at the time. Marof realized that any attempt to build capitalism in Bolivia would entail the building of a neo-colonial economy, and would end up with Bolivians forever chained to US capital. He proposed that socialism could be built directly, by nationalizing the Bolivian mines and by returning the land to the existing Indian communities, hence his slogan “Las minas al Estado y la Tierra al pueblo”. In the fragments below, Marof claims that there is no land more fertile than America, and within it no country better than Bolivia to proceed to communism, due to the existing Incaic culture. Indeed, the Incas are believed to have a tightly and centrally planned state that redistributed resources across its empire through a palace economy and leveraged collective work through institutions such as the mita. While Marof may over-romanticize the past, it is clear that the palatial economy of the Incas provided much more welfare to the people of the Tawantisuyu than the post-Colombian period ever would. As Steve Stern details in Peru’s Indian People and the Challenge of the Spanish Conquest, the new European arrivants would corrupt the system, and force the inhabitants to work to death in the mines, forever destroying this paradise. Indeed, between the fragments below we can find the repented confession of a Spaniard who realized they had corrupted excellent people.

Just after the 1920 coup, the PR would split into its more moderate “authentic” and more radical “socialist” factions. These were not radical enough for Marof, and on his return to his homeland he would found a new party of explicitly Marxist socialism. The late 1920s had brought a turn to the right of the government, and Marof, about to be elected to parliament, would be exiled after an accusation of plotting to install communism. His exile through Latin America would lead him to constant strife with fellow communists, especially over the nature of the post-revolutionary Mexican state, and over Trotsky’s exile. A particular figure of importance that Marof would meet and share ideas with was Mariategui. Indeed, it is said that the Mariategui’s ideas of indigenism originated, or at least were very shaped, by his meeting with Marof, as La Justicia del Inca is prior to Mariátegui’s seminal Siete Ensayos, even if it cannot be denied that Mariategui took a way deeper study of his own present conditions. During his exile, Marof would found the “Tupac Amaru ” group, with an express focus on Marxism and Pacifism against the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay. Tupac Amaru would then later merge with other forces into the Trotskyist Partido Obrero Revolucionario (POR). This is hardly surprising, as Marof’s ideas rhymed well with the Trotskyist opposition to the crude stageism espoused by the “Official” Commmunist Party tied to the Comintern.

The POR would play a large role in the Bolivian revolutionary period between the 1954 Bolivian revolution and the 1964 coup by Barrientos that put an end to it. This period was an extremely radical transformation that is even more forgotten than the Mexican revolutionary period of 1910-20 and merits an essay of its own. During this period, Marof slowly blends out of history, producing mainly scholarly work and taking a second line seat to other more protagonists like Guillermo Lora and Juan Lechin. He eventually passed away in 1967.

The fragments we translate below compromise three parts of a longer work. They show not only his commitment to an indigeneous (and sometimes overromantized) strain of communism, but also the seriousness of his political thought. He understood what it took others to find out: that neo-colonial countries need not start up a capitalism of their own because they would never be able to break out of dependency. Marof also discusses the role of planning in the Incaic palatial economy, how surplus should be allocated, and dissects the concepts and duties of freedom for those living in a communist society. In the wake of another radical period of Bolivian society where indigeneity is taking a front role, we present the text below to bring attention to a thinker that is almost unknown. His ideas written down almost a hundred years ago influenced many, and prefigure debates on communist freedom and communist virtue which are still important today.

Ama Sua Ama Llulla Ama Kella1

During the period of Inca domination, the people of what is today called Bolivia undoubtedly enjoyed greater benefits than what the republican regime gives them today. In that happy and distant time, politics was not known, and consequently there were no personalistic and bloodthirsty factions that destroyed each other. Life was calm, simple, laborious, and it went on singing eclogues with no other aspiration than that of the happiness of the community through labor.

The Incas – great statesmen whose wisdom to govern peoples has never been sufficiently praised and has instead been forgotten with a regrettable injustice both by the Spaniards and by the children of Spaniards – ruled their people in such a way that every inhabitant had his life and his future assured. It is after the arrival of the conquerors and during the long years of colonialism and of those named republicans, that the inhabitants became involved in a series of problems and concerns that until today cannot be solved, and which will only be solved the day that we return to the land and give each inhabitant their economic independence. That is, together with giving land, we give them the idea of organized and community labor.

Without a doubt, a people cannot be formed without first establishing the material bases on which the other branches of society must float. To have willed making a simple and hardworking people who did not know the value of money, – and who until today do not give it their full appreciation, – who ignore individualistic gestures, which represent a special race that is accustomed to these exercises for centuries, I say, to have wanted to make this Indian people of America into Europeans, and to have given them all the habits of Europeans, has been the great mistake of politicians for a hundred years.

The civilization of the Incas, which understood the race and psychology of its inhabitants, did not hand over the organization to the whim of an individual, nor did it allow the disruption of the system. Judicious and authoritative organizers were in charge of regulating everything. From the time an individual was born, his bread and his future were assured. People of conscience made each inhabitant know their duties by gently accustoming them to honest and simple labor. These organizers, who were not individualists, had a passion and interest for the whole which is not seen or equaled to this day.

This civilization was in fact not only far-sighted but was also fraternal and had high moral standards. Its code is simple and eloquent. With three words the whole gospel has already been said. Any modern society should be proud to own it. When they said: “ama llulla, ama sua, ama kella”, they meant it and they practiced it.

A civilization that did not make literature about morality and that punished the lazy, the dishonest and the thieves with severe penalties is a surprising example in history. The spirit marvels to know that everything could be excused to a man except him being lazy. The ancients said all other vices spring from laziness and they were right. This is why the Incas recommended to their governors that they always keep their subjects busy with useful work for the benefit of the spirit and the body. You have to admire them without reservation in this. They legislated and organized labor in such a way that in their Empire neither misery nor the pain of hunger was known. Nor did they neglect the health of the soul, because if historians paint the Incas as tough, fair, and impassive, they were also describing them as poets. The Empire was permeated with poetry and art. When you talk to a Quichua, they dramatize everything, and even work is a romantic note for them. Their sweetness and affability are proverbial.

When we remember in this present time that it was just a few centuries away, or that large silhouettes are evoked by living chronicles in silver nights, the hand unintentionally approaches the visor, the imagination is elevated and a deep respect piously takes hold of us. It is necessary to return to the source, and to convince our conscience that the happiness of our people is found on this land just one step away from us. Let us organize the last descendants of the Inca, let us return to the fraternity, give each inhabitant land and bread, and make fun of all the democratic charlatans of the globe.

The Communist Idea

The honestly communist idea is not new in America. Centuries ago, the Incas practiced it with the best of success and formed a happy people that swam in abundance. The laws that existed were rigid, severe, and just. No one could complain of misery without unjustly sinning. Everything was wonderfully planned and financially regulated. The good years served as reserves for the bad ones. The harvest was scrupulously distributed and the Inca state revolved around a system of harmony.

Mr. Rouma in his interesting work, “L’Empire des Incas”, observes that, far from diminishing the rigidity of the system over time, it strengthened and acquired new vigor. And is that no member of the community lived discontent. They all ate freely and were happy. Crime was unknown, and a tutelary shadow of refined honesty hung over the empire. There was only one misdemeanor: laziness.

The Incas wanted to realize their ideal throughout America and they would have done so without the disputes of Huáscar and Atahuallpa, and the arrival of the Spanish. Already their famous empire before the conquest extended to near what is now Colombia and to the south and east, it crossed the provinces of Santiago del Estero, Córdoba and Tucuman.

These magnificent Incas, so wise and meticulous about the general welfare, truly constitute the only civilization that America has known, and it is never possible to equal them in virtue and prudence. Today, four centuries after them, and in the middle of the Republican period, we find ourselves disoriented and stagnant. But this does not mean that another more vigorous and modern communism cannot sprout from the ruins of the Empire and revive the ashes of the old Quichuas, because neither the wind nor the conquest with all its cruelties have been able to extinguish them or to destroy the most sober and intelligent race of America.

When one reads the chronicles of those fantastic times, one is amazed that the human species had reached such an advanced degree of economic and moral perfection. Without wanting to, enthusiasm sprouts and the hands tremble along with the heart. They were not brutal warlords, nor did they breed disorder and adventure. Prudent and thoughtful they were interested before the little glory or the plume that puffs up the luck of all. Optimistic philosophers only believed in the earth and loved it dearly, while their thoughts went to the methodical organization of a group, of a hundred, of the last of the community. Practical men knew that man lives on bread before anything else, and their efforts were to solve this problem that was not difficult in a fertile and lavish land like a mother. The rest, the ideas of art, astronomy, poetry, etc. They sprang from the sweetness of the race and the magnificence of nature. And those who made poetry and art were solid and capable heads whose natural and advantageous inclination was maintained by the State.

All the Inca aspiration, both for prestige and for good government, strives to give the State all its potency. In a simplistic time, that sovereign State was constituted by the Inca. The state was the owner of the land, animals, pastures, gold, silver, precious stones. The Inca jealously distributes all these products, and guarantees the economic existence of the Empire, managing it by means of rigorous accounting. Everything comes to his knowledge. He knows how many inhabitants a region has, how many are born in a year, how many have died. A special caste of functionaries brings him up to date with the most minute details.

The historian does not have much to tell about the Incas’ warrior deeds, but instead of the great acts of administration. Their very conquests have no other purpose than to spread the economic well-being among the barbarian tribes. Their captains wage war without the idea of robbery and pillage. The act of conquest is secondary. When they wage war they organize the loser instead of taking advantage. Nor do they subjugate and enslave him. They forgive the prisoners and dress them all at the Inca’s expense. They let the conquered peoples be governed by their former captains while hinting at Inca methods. The historian Luis Paz tells us, in his history of Upper Peru, that when the Incas conquered the Araucanians, after much bloody and hard fighting, they found them in such a state of misery and barbarism that the Inca could not contain himself from crying. The inhabitants could not but count to ten, they lived naked and they supported themselves by hunting and fishing. The Inca immediately ordered that the prisoners be given clothing and the people instructed in agriculture. As it is understood, this way of governing surrounded them with great admiration throughout the continent, which in practice was translated into the adherence to the Empire of vast settlements. For their part, the Incas developed a very skillful policy that earned them sympathy. They did not go against the religious sentiments of the subject or adhering tribes. On the contrary, they honored them. In Cuzco, the capital of the Empire, pompous tribute was paid to all religions. This example of wisdom and kindness immediately contributed to the fusion of all peoples. In the long run, the only thought would be that of the dominant religion of the Sun, and the Inca mold did nothing more than translating the triumph of communist politics.

Their discipline was so solid and so unshakable that the Spaniards, not being able to destroy it, took advantage of it, but not with an altruistic purpose like that of the Incas but with that of favoring their greed and their insatiable appetite for gold. That is why the Empire fell, the jealous centurions (ilacatas) were replaced by new men who from the beginning abused all privileges. Instead of the simple priests of the sun, the old cross that was already discredited and inglorious in the West was imposed by blood and fire on the altars. But even today the spirit of the Quichua through the centuries remains standing. The Republic, with all its lyricism and its proclamations, has not conquered their heart. And in short, this republic is nothing but the happy creation of some doctors for whom twenty percent of the population is killed by the knife on the day of an electoral farce. The original race remains inexorable and far from the supposed democratic conquests, waiting for the return of its old formulas and its great morality destroyed by the lust of the conquerors.2 But wanting to implant communism in the Inca form is still a bitter dream at the present time. Times have changed, Western civilization with its inventions, its machines, its greed and its sordidness, although we refuse to believe, also lives among us. On the other hand, democracy, although falsely interpreted, separates us from the road. Owners of republican life are in fact the petty-bourgeoisie – natural enemies of the indigenous – who made the liberating revolution and fortunately followed Bolívar. But for this caste, any economic reform in the sense of equalizing the social and economic conditions of the indigenous native would be a contradiction in terms. And the truth is that the indigenous people have the right to this reform because they constitute in certain republics of America up to eighty percent of the population, they work hard and yet they live in slavery and misery. This is why heroic remedies are imposed.

As long as there are fierce semi-enlightened governments that, in short, think that economic freedom is reduced to lyrical discourse and the opportune madrigal, theoretical and material demagogues, who have solved the problem of the republic by taking the most succulent slices for themselves, this matter is lost. From when Castell came with an Argentine expedition, until today, a sentimental cry is being made for the equality and education of the Indian. President Morales, self-titled protector of the indigenous class, and other presidents, have had the naivety or the bad faith to try to improve their sad condition with decrees that are either not fulfilled, or that are impossible due to the poverty of the national treasury. So what must be done is to discard the political phenomenon and abandon it to the bourgeoisie. What does a plebiscite matter to the indigenous people! The proletarian class must simply demand its economic equality. Everything that is done in this regard is honest and fair. The American continent is the continent made for socialism, where it must bear its best fruits. The land, the environment, the common origin, the lack of lineage and fatal prejudices, predict it. Here they came to our land, naked Europeans without shoes, to eat our bread. Everyone should know that the only privilege in the new world is honesty and the only crime is laziness; that not even those born with talent can boast of this privilege which cannot be bought but which nature distributes for the good and social improvement.

However, it is not difficult to liquidate prejudices, nonsense and vested interests, in good harmony. The feisty and formidable spirit of the new continent cannot sit idly by waiting for material evolution. The spirit and coexistence must precipitate the socialist era without having any illusions that a prior development of capitalism is necessary. And here I want to stop for two minutes. The development of capitalism in the new states will only lead them to deliver them bound hands and feet to the Yankees. As our societies progress, the lack of a national capital, the lack of private initiative, and the fierce cries for foreign capital as an urgent need, will only result in these capitals coming, raising their arms and concluding by destroying their sovereignty. That is why I maintain that the American Revolution should not wait for capitalist flourishing but rather trap the national capital at every point and harmoniously seek its own development at the same time as its power.

The capital of America is the mines, the oil, the thousands of arms, the intelligence put at the service of the State. The rest does not lend itself more than to silly legends of sovereignty, when deep down all the countries of America, considered from the European point of view, are no more than colonial, without any political personality.

Social organization

A great organized community is the great dream of today’s new men. A community where men shake hands with men in wide loyal gestures, where everyone speaks to each other in a brotherly manner and without double-mindedness, where associates cater and work without being taxed by Europe or the United States.

This test can and must be done in Bolivia. No nation in America is as vigorous, as rich in wealth, and has the communist past as this one. And it will lose nothing in the experience of returning to the old and happy life that was diverted by the conquest. Many centuries before, these provinces were administered by the Incas with the best of successes. The Collasuyo was magnificent for their plans, and the communist idea and realization triumphed centuries ago in America. All the tests were done, the town was organized into families, into centuries and into large agricultural communities under the watchful eye of the central axis. The people thus organized never protested the regime to which they were subjected, on the contrary, the adherents grew, and the forward-looking communism gave its most opposing fruits. The small and large details, family life, fellowship, travel, traveler inns, temples to the Sun, art and science, everything was planned and regulated. Following Mr. Rouma in his commendable brochure “L’Empire des Incas et son communisme autocratique”, these latter words to satisfy the Belgian liberals. In addition to that, M. Rouma, married to a wealthy and rentier woman, finds it a bit dangerous to use inordinate praise for the Incas without naturally objecting to the communist system. That is why the subtitle is significant. The reader knows what it is about. A perfect but autocratic communism. In any case, the good connoisseur will understand, when Mr. Roma, satisfying his thirst for a scholar, gets to write this paragraph: “It cannot be denied that an administration that ends up radically suppressing poverty and hunger, which reduces crimes and offenses to a minimum that no modern civilized nation has ever reached, that makes order and security reign, that ensures impartial justice, that ignores the existence of social parasitism of the lazy, the badly rich, the speculators, etc. constitutes a unique phenomenon in the world and deserves our most complete admiration”.3 After saying this and obeying his petit-bourgeois nature, very enthusiastic about liberal principles and privileges – a chalet and athenaeum liberal- he adds that, nevertheless, this beautiful civilization was equal to a mechanism moved by a central axis where the individual or freedom did not exist. How many nations that live in disorder and anarchy would not wish to be moved by a single central mechanism that watches over, organizes and brings happiness! The enormous British Empire whose manifest organization and seriousness never denied, is it not perhaps a great modern mechanism? Have the disciplined German people not tried to conquer the world? Are not the Romans a great piece of history? Let us leave freedom to weak, disorganized nations that are eaten up by an unhappy philosophy.

The Quichuas, great statesmen, understood that this rigorous state mechanism was precisely what guaranteed them abundance and peace, because without this order in their life and that prudence in their actions, they would have returned to the primitive source where crime and violence. misery was frequent.4

Freedom in fact and in practice was better understood than today. The Quichua, after fulfilling his obligations, a travail pas trop penible, adds M. Rouma, could rest or distract his spirit. The field was eternally green and joyous and wherever it went there was always an open door and a friendly and brotherly hand. The current civilization with all its machines and inventions has not brought us, on the one hand, that comfort at a very expensive price, and on the other, the werewolf, the wolf of bail and industry, who has a thirst for vileness and insatiable blackness. This singular man, who for the law, civilization, and justice wages fierce wars and kills each other. Who in homage to freedom assassinates defenseless races and distributes the oil fields and mines; who has divided today’s society into two definite classes that hate each other. Famous western civilization! I have traveled all the states of Europe and have lived for several years in one of the most industrialized countries, in Great Britain, and I have seen with my own eyes, the long lines of workers dressed in rags, some without shoes, black from coal, and exhausted from work, sleep under a canvas tent and fed by just a loaf of bread and a cup of tea. In this powerful country, I have seen how the workers live by sharing one room between eight, with no hygiene, without bedding, without fire in winter, in the most appalling misery. And even worse things I have witnessed in that industrial country of lords and slaves.5

Wanting to overthrow Inca communism with the infallible argument that liberals or millionaire democrats claim, is not understanding what brotherhood means when it is practiced from the heart, giving it all its reality and its value. Men can easily get used to being very free on the condition that they live by hunting and fishing. But when freedom is widely proclaimed, those same bourgeois democrats call it anarchic and persecute it. The people of the city must remember, even though they may want to avoid it, that they have to eat and dress, and for these pressing needs it is necessary to work hard without all their effort being rewarded and without having any security in the future. For this, it is better to live within a regime that organizes production and wealth. Freedom at the present time is reduced to practically nothing. A beautiful poetic plot! Freedom within the current period of civilization is a privilege of the chosen, of capitalists, of profiteers who, thanks to their cunning and talent, placed at the service of the strongest or of crime, enjoy it as an unlimited inheritance. These will be the only ones who can dream on the côte d’azur, Mr. Rouma! As for the millions of workers, they hardly have the freedom to take the tram that will take them to the factory and to glimpse the delights of nature through an eighth-floor window. The famous English liberty, after the war, has been reduced to letting the pipe smoke everywhere! … When the poor English go to the countryside, they only have a path to walk. On the right and left, large insulting and aggressive signs against poverty warn that anyone who dares to step foot on private property will be prosecuted and persecuted. The shade of the trees, the air we breathe, the pheasants, also constitute private property …

If freedom were a palpable, tangible fact and something man could conquer forever, if it were possible to return to the primitive and human state, without laws, without police, without modesty or honor, man as absolute owner of his life and his actions without knowing what is a crime – since there are no laws there would be no crimes – and if above all, it were very easy to live on fruit trees, hunting and fishing, I would be in love with freedom, just as was Jack London, the great American writer. But like all this, it was nothing more than a dream of Rousseau, a theoretical and wonderful dream that had the virtue of enthralling the men of the last century and even some today, backwards thinking for convenience, and certain politicians who exploit it wonderfully for their electoral purposes. I am in favor of organizing society within a more human and just realistic sense, using all forces, whether they come from man or nature. This is what the Incas did more than five centuries ago and they had the greatest of successes, and this is what we must do at the present time. To return to the same communism with the advantages of modern advances, with the perfected machine that saves time and leaves the spirit free for another kind of speculation, is not a literary rambling or a fantasy in a country full of resources of all kinds that only audacious hands and convinced workers await. The dangerous thing is to live without a compass or to disorderly imitate civilizations that have another origin and unforgettable prejudices. In fact, in Europe, revolutions and things take centuries. Small details cost rivers of blood because it is the natural homeland of selfishness. Civilization of iron and blood! In our America, man is more daring, more courageous and more selfless. Things go on impatiently, spurred on by an insatiable thirst for improvement. There is a desire for improvement that has not been sufficiently understood. Then, people fraternize easily and forget grudges and hatreds. Our direct way is to go toward a purely American communism with its own manners and tendencies. We have two things in front of our eyes that assure us success: the fertile land ready for every trial and the industrial improvement that we freely collect from the Western civilization. Then we will not lack prudence, talent and justice, to make good use of the machines and serve us in the interest of all.