Border control offers nothing to the working class and must be actively opposed in favor of a roadmap to a borderless society, writes J.R. Murray.

Toward the end of 2018, Angela Nagle, leading partisan of the “anti-identitarian” Left, wrote a piece called The Left Case Against Open Borders, published in the right-wing journal American Affairs. It received a lot of attention, as contrarian takes often do, because it flies in the face of over a century of Marxist theory and strategy. Nagle puts forth the following argument: historically, the socialist Left has been pro-borders and anti-immigration. The Left has only recently adopted it’s anti-border position. We have done so as a knee-jerk reaction to the rise of Trump and the nativist Right, and because the elites have duped us by “wearing a mask of virtuous identitarianism.” Mass migration is an exploitative system which causes brain drain in developing countries, the exploitation of immigrants as cheap labor in developed countries, and is used by big business to drive down wages and attack unions. Since certain sections of the capitalist class support open borders, this means the anti-border Left is tacitly giving its support to and aligning itself with the capitalist class. Mass migration is unpopular for all of the above reasons and if the Left ever wishes to take power it will have to make a choice between embracing popular pro-border sentiment or allying with libertarian capitalists to suppress the masses and open the borders. In the end, immigration and open borders serve the rich elite, and the only way to end mass migration is to end global inequality, anti-labor free trade deals, and the imperialism of both global finance and the Pentagon.

This argument is not a “left case against open borders” but an essay-length dog-whistle written in an attempt to attract working-class elements of the far-right to social democracy. It knocks down straw men, misinterprets the Marxist position on borders, ignores nuance, and falsifies history. What follows is a debunking of Nagle’s claims and an argument for the abolition of borders.

Revisionist History

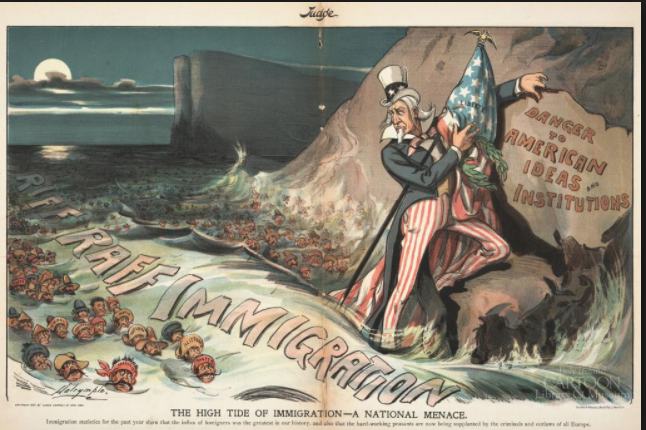

Nagle asserts that “the transformation of open borders into a ‘Left’ position is a very new phenomenon and runs counter to the history of the organized Left in fundamental ways.” It’s a bold claim, in that it is barely even a half-truth. The ambiguity of the term “organized Left” allows for Nagle to construct a false narrative of U.S. labor history. What Nagle means by the “organized Left” is unions, specifically anti-socialist unions like the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Unions are a powerful tool that have helped to extract massive concessions from the capitalist class and protect workers from the worst excesses of the capitalist system. But the union movement is ideologically broad. The AFL (now the AFL-CIO), the largest union confederation in the United States, has been anti-socialist since its founding. The Left calls these types of organizations “business unions.” Business unions are run by bureaucrats set on partnering with employers to stave off labor unrest. A major project for socialists in the United States today is to wrest power back from these bureaucrats and/or build entirely new organizations. Nagle’s argument is essentially a defense of the worst politics to come from the right wing of the labor bureaucracy. Despite all the talk of universalism from “anti-identitarians” like Nagle, her argument exists in contradiction to the more universalist approaches to class struggle. She puts forth the domestic American worker as the historical subject of U.S. labor organizing despite a rich history of socialist solidarity with immigrant workers. She erases this history to advance the erroneous claim that the entire left has been pro-border until a misguided turn to identity politics.

Historically, there has been an alternative to business unionism, such as the IWW and the CIO, the former being decidedly socialist and internationalist. Additionally, the working class has not only organized itself through unions but also through a number of different political parties that aimed to bring the working class to power and end capitalism. It is only by ignoring radical unionism and working class parties while narrowly focusing on anti-socialist business unionism that Nagle can make the argument that the organized Left has been anti-immigration and pro-borders. One can trace the importance of internationalism and the abolition of borders from Marx to Debs to Lenin to Luxemburg, American Trotskyist parties, Che Guevara, Fred Hampton, and all the way to socialists today who have fought and continue to fight for immigrant rights. It is not a new phenomenon, and certainly not merely a reaction to Donald Trump.

Useful Idiots

Nagle wholeheartedly approves of business unions’ perspectives on immigration. She argues:

From the first law restricting immigration in 1882 to Cesar Chavez and the famously multiethnic United Farm Workers protesting against employers’ use and encouragement of illegal migration in 1969, trade unions have often opposed mass migration. They saw the deliberate importation of illegal, low-wage workers as weakening labor’s bargaining power and as a form of exploitation. There is no getting around the fact that the power of unions relies by definition on their ability to restrict and withdraw the supply of labor, which becomes impossible if an entire workforce can be easily and cheaply replaced. Open borders and mass immigration are a victory for the bosses.

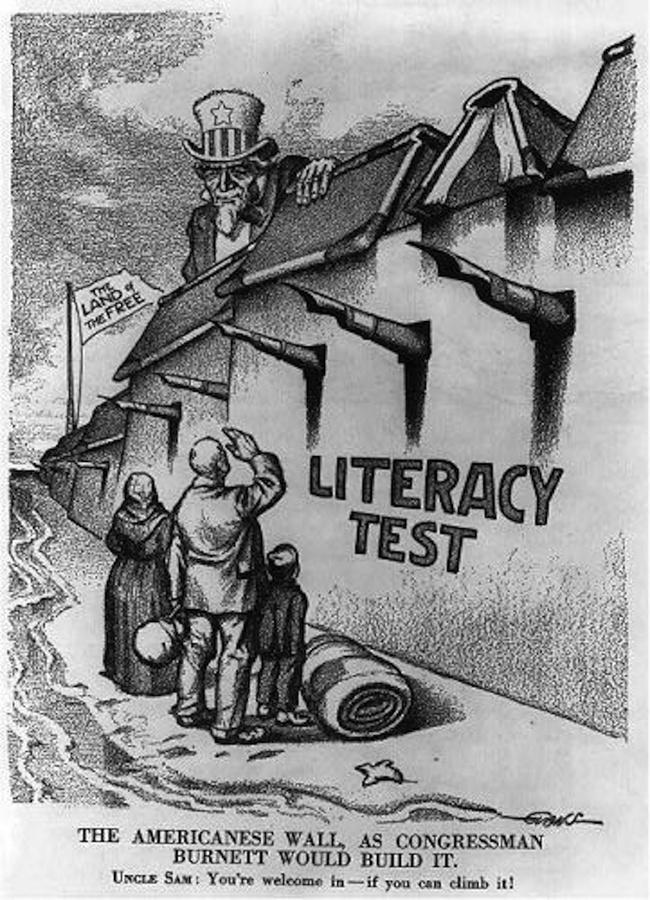

Employers often do use undocumented immigrants to break strikes, flood the labor market, and drive down wages, but Nagle completely misdiagnoses the root of the problem. The distinction between legal/illegal labor, only possible through the existence of the border, is a powerful weapon in a capitalist’s arsenal. Undocumented workers live in fear of being arrested and deported. Employers use this fear to bully and threaten these workers into accepting lower wages. If they try to organize for better pay or working conditions, their undocumented status becomes an enormous liability — the workforce can simply be deported and replaced. The ease with which undocumented workers can be exploited by their employers undercuts legal laborers (both organized and unorganized) and breeds nativism in their ranks. It is a wedge used to divide the working class. The solution is not to be against immigration, but to organize all workers, regardless of legal status, and fight for an end to the legal/illegal distinction. Immigration and open borders are not a victory for the bosses; in fact the opposite is true: the abolition of borders would entail the end of the illegal/legal distinction that employers wield to keep workers divided and wages down.

Nagle ignores this common socialist argument and instead chalks up socialists’ pro-immigrant/anti-border stance to a misguided moral impulse:

With obscene images of low-wage migrants being chased down as criminals by ICE, others drowning in the Mediterranean, and the worrying growth of anti-immigrant sentiment across the world, it is easy to see why the Left wants to defend illegal migrants against being targeted and victimized. And it should. But acting on the correct moral impulse to defend the human dignity of migrants, the Left has ended up pulling the front line too far back, effectively defending the exploitative system of migration itself.

Nagle believes the U.S. deportation machine and Fortress Europe are obscene, but she cannot see that ICE, the mass drownings in the Mediterranean, and detention centers are all the direct result of borders and the criminalization of immigration. There is no middle ground here; as long as the border exists people crossing it will be deemed criminals.

She continues this accusation that we are simply bleeding hearts unable to rationally analyze border policy:

Today’s well-intentioned activists have become the useful idiots of big business. With their adoption of “open borders” advocacy—and a fierce moral absolutism that regards any limit to migration as an unspeakable evil—any criticism of the exploitative system of mass migration is effectively dismissed as blasphemy. Even solidly leftist politicians, like Bernie Sanders in the United States and Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom, are accused of “nativism” by critics if they recognize the legitimacy of borders or migration restriction at any point. This open borders radicalism ultimately benefits the elites within the most powerful countries in the world, further disempowers organized labor, robs the developing world of desperately needed professionals, and turns workers against workers.

Recognizing the “legitimacy of borders” and migration restriction as a way to protect domestic laborers and reserve access to parts of the welfare state, real or desired, for American citizens only, is nativism by definition. If the term “useful idiot” is being thrown around, then it should be applied to Nagle and her cohort who provide cover for far-right nationalists. Socialists support immigrant rights, including demands like open borders, not because the left has abandoned labor for “social justice” issues, but because they must organize the working class, millions of whom are immigrants. The question is not merely one of moralism but of the necessities of class struggle and organizing the working class as a class.

It would be interesting to hear Nagle answer the question “what makes borders legitimate?” To recognize the legitimacy of borders means accepting everything that comes along with that legitimization. If borders exist, then they must be defended. In order to defend the border, force must be used. A closed border is a militarized border, and a militarized border is a place where poor people are terrorized, brutalized, and even murdered. Borders can only be maintained through the use of fences, guns, deportation, and detention centers. By arguing that any call for an alternative to this system is just “moralism” is to ignore the possibility of a world beyond this system of terror.

Nagle consistently refers to mass migration as an “exploitative system” that bleeding heart moralizing leftists are propping up. But mass migration is not a system. It is a social phenomenon, a consequence of imperialism, the creation of a global market in labor, and climate change. Nagle contorts the stance of supporting victims of these consequences into the stance of supporting the consequences themselves. For her, to support open borders means supporting the exploitation of cheap labor by employers, supporting brain drain from the third world, supporting the tragedy of people having to uproot their lives and move to the United States. But we support open borders precisely because we recognize the tragedy and horrors that imperialism, global inequality, and climate change produce. Immigrants leave their homes because they are forced to. We demand that their trauma is not compounded by the violence inherent in maintaining a border.

Nagle assumes that the demand for an open border exists in a vacuum. She lists a set of demands in place of open borders:

Reducing the tensions of mass migration thus requires improving the prospects of the world’s poor. Mass migration itself will not accomplish this: it creates a race to the bottom for workers in wealthy countries and a brain drain in poor ones. The only real solution is to correct the imbalances in the global economy, and radically restructure a system of globalization that was designed to benefit the wealthy at the expense of the poor. This involves, to start with, structural changes to trade policies that prevent necessary, state-led development in emerging economies. Anti-labor trade deals like NAFTA must also be opposed. It is equally necessary to take on a financial system that funnels capital away from the developing world and into inequality-heightening asset bubbles in rich countries. Finally, although the reckless foreign policies of the George W. Bush administration have been discredited, the temptation to engage in military crusades seems to live on. This should be opposed. U.S.-led foreign invasions have killed millions in the Middle East, created millions of refugees and migrants, and devastated fundamental infrastructure.

In fact the anti-border Left agrees with all of these demands. The hard truth is that the above terrible things are happening and socialists must fight to defend people fleeing the from the resulting poverty and violence. Why would we support the border security apparatus that harms people fleeing from the violence and inequality that we demand an end to? Nagle gives us insight into her reasoning when she states,

But whether they like it or not, radically transformative levels of mass migration are unpopular across every section of society and throughout the world. And the people among whom it is unpopular, the citizenry, have the right to vote. Thus migration increasingly presents a crisis that is fundamental to democracy. Any political party wishing to govern will either have to accept the will of the people, or it will have to repress dissent in order to impose the open borders agenda. Many on the libertarian Left are among the most aggressive advocates of the latter. And for what? To provide moral cover for exploitation? To ensure that left-wing parties that could actually address any of these issues at a deeper international level remain out of power?

Instead of doing the work to convert chauvinist, nativist elements of the U.S. working class to internationalism and socialism, Nagle hopes to harness their racism as a way to build electoral support for social democracy. It is a cynical calculation: if Corbyn or Sanders simply take a right-wing view on immigration, then they will get more votes.

Nagle asserts that a political party wishing to govern will have to choose between accepting the “will of the people” or repressing dissent in order to enact open borders. This is a false dichotomy that must be rejected. Socialists have the responsibility of explaining our position and convincing the U.S. working class of their shared interest with immigrants in fighting the capitalist class, working toward socialism, and abolishing borders. To become a class that can govern in the interests of all humanity, the working class must go through a protracted process of political struggle and education, transforming itself as a class in the process. Chauvinism within the working class is not something revolutionaries should bend to, but fight against. This is not elitist — it is chauvinist ideology that is elitist.

In a particularly cynical move, even by this piece’s standards, Nagle warps Marx’s words in defense of her pro-border position:

Marx went on to say that the priority for labor organizing in England was ‘to make the English workers realize that for them the national emancipation of Ireland is not a question of abstract justice or humanitarian sentiment but the first condition of their own social emancipation.’ Here Marx pointed the way to an approach that is scarcely found today. The importation of low-paid labor is a tool of oppression that divides workers and benefits those in power. The proper response, therefore, is not abstract moralism about welcoming all migrants as an imagined act of charity, but rather addressing the root causes of migration in the relationship between large and powerful economies and the smaller or developing economies from which people migrate.

Here is Marx’s original letter that Nagle quotes. Marx did point out that low paid migrant labor is bad for domestic and migrant workers, but he did not advocate for the legitimacy and maintenance of borders as a solution. Instead, Marx wrote about the necessity of the working class residing within two different nation-states uniting to fight their common oppressor. This would entail the English working class fighting alongside the Irish working class for the end of English colonialism in Ireland. It would also include Irish workers residing in England uniting with English workers to fight for better wages, working conditions, and socialism. This is the same strategy advocated by the anti-border Left today.

A socialist, borderless, future

Abolishing borders is essential to building socialism. Unfortunately, Angela Nagle and the milieu around her have no intention of building socialism. Their goal is the creation of a reformist electoral party that can win elections and implement social democracy. They dream of universal healthcare and free college tuition for every American citizen while keeping everyone else out through deportation, fences, and an e-verify system that ensures no undocumented worker will find employment. Of course, they pay lip service to ending imperialism and global inequality, but these are essential features of capitalism, which social democracy cannot transcend.

To build socialism we must first build a working-class party with a political program. In our program, we will need to lay out and patiently explain our position on immigration. Our position should not be to maintain borders while we try to end imperialism and global inequality. Our position should be to smash the capitalist state apparatus, replace it with a workers republic, and begin the process of abolishing all borders — not as an idealist fantasy but as a necessary part of building socialism.

At a minimum our program should explain that a workers’ government will immediately:

- Abolish ICE and CBP

- Abide by the internationally recognized asylum process

- Abolish all immigration quotas and limits

- Eliminate all fees associated with applying for a green card or visa

- Give amnesty to all undocumented immigrants currently residing within the United States

- Grant citizenship to any permanent resident living in the United States for at least a year

Additionally, our program should explain our long term goals regarding borders and immigration. Examples include signing agreements with future socialist governments, ending all border and travel restrictions between these countries, and working towards a common citizenship shared by residents of all socialist countries that recognizes universal rights for all humans of the world, working towards a notion of global citizenship as a step toward abolishing the concept of citizenship altogether (which is tied to the sovereignty of the nation-state).

These demands are not, and will not, be made in a vacuum no matter how hard Nagle wishes to characterize them as such. Socialists must organize documented and undocumented workers alike, as well as recognize the special revolutionary potential of migrants, whom Badiou calls the “nomadic proletariat.” Immigrant workers carry traditions of labor activism with them and are often at the vanguard of class struggles. Mass migration is part of what makes the working class a class with no country. The struggle against borders is a class struggle, one that goes beyond mere economic implications. Socialists must make connections and work with workers’ organizations in other countries, end foreign coups and occupations in foreign countries, end funding, training, and arms sales to despotic regimes, appropriate and redistribute money and property from the capitalist class, etc. Fighting for and eventually building socialism will go hand in hand with abolishing borders. It is a unitary process. The moment the two are separated is the moment socialism is no longer a possibility.