On this episode of Cosmopod, Donald and Parker welcome Cosmonaut author Josh Morris on to discuss the history and historiography of the US Communist Party. Academic accounts of the party have largely fit in two camps; Josh’s upcoming book The Many Worlds of American Communism attempts to go beyond the standard story and rethink the scholarship for a post-Cold War era. Below we have included a preview of Morris’ book which is based on the preface.

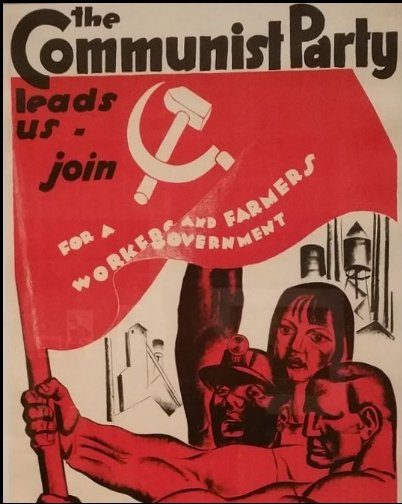

In 2019, amidst a wet and humid June afternoon, the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) held its 100th anniversary conference. There, members young and old gathered to meet and greet as well as vote in the new generation of Party leaders. The conference numbered over 500 and attracted a large number of youth activists ranging from students to hard working young adults. In recent years, a growing interest in the concepts of Marxism, communism, and anarchism developed around the world as the international economy reached a crisis point during the 2008 recession. After the publication of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century in 2013, which unveiled systemic conditions about income inequality throughout the modern world system, sales of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital soared throughout Britain and the United States. He Nian, a Chinese theatre director, re-created an all-singing, all-dancing musical to commemorate Marx’s work in 2014. English literature professor Terry Eagleton published Why Marx Was Right in 2011 while French Maoist philosopher Alian Badiou published The Communist Hypothesis to rally activists into a new era of communist theory.1 In the 2016 American Presidential Election, the CPUSA ardently advocated for opposition against Donald Trump in a manner that mimicked their historical attitude toward the ‘lesser of two evils thesis,’ earning them both attention and criticism from American activists, leftists, students, and unionists. Finally, in November of 2018, the Historians of American Communism gathered in Williamstown to discuss the 100 years of American communist history and its legacy in the United States.

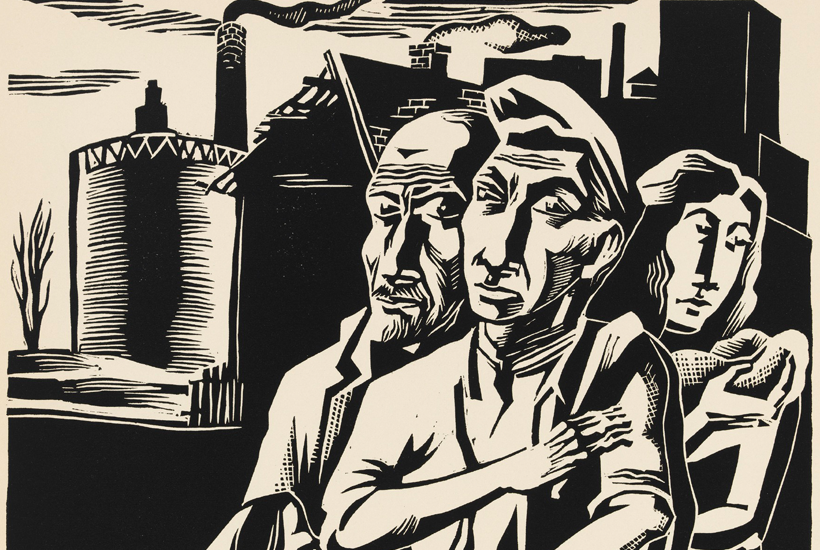

My research examines the American communist movement from its origins in the spring of 1919 until the transition into what is increasingly being called the New Communist Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. I examine the role of communists in U.S. history by dividing up the narrative into multiple worlds of activity and engagement; particularly political activism, labor organizing, community organizing, and the experiences of anticommunism. I argue that American radicalism in the 20th century took on features that distinguished it from a specific effort, such as civil rights legislation or collective bargaining agreements. Whereas communism as a movement in the United States has been depicted historically as a rather exceptional and unique movement, I understand it as an expression of American radicalism. American Communism has a difficult and sometimes contradictory history; conflated between questions about ideological motivation and the practical gains netted by both American workers and citizens as a result of such motivation. American communist history is not a history of organizations, nor is it a history of how certain ideologies had effects on the actions of individuals. It is a history of people at the grassroots and how they chose to balance their lives within the context of American democracy and through the ideals of Marxian socialism.

This research asserts that American Communism can be understood in a variety of ways depending upon the context from which the examined organizers and activists engaged with American citizens. As Perry Anderson pointed out, to write a history of a communist party or movement one

“must take seriously a Gramscian maxim; that to write a history of a political party is to write the history of the society of which it is a component from a particular monographic standpoint. In other words, no history of a communist party is finally intelligible unless it is constantly related to the national balance of forces of which the party is only one moment, and which forms the context in which it must operate.”2

People engage in social movements with a passion that expresses the very conditions of societal pressure and a desire to change specific said conditions. When one examines the work of communist political activists, they will find experiences that unveil a deeply ideological political movement. By switching to an examination of communist labor activists, one reveals a much different narrative; focused on legal strategies for obtaining collective bargaining rights, and cared less about the conclusions of a political committee than it did the demands of local workers. Finally, if one examines the work of communist organizing in the communities against institutionalized forms of societal oppression, they will find a more emotional and cultural narrative that sees American radicals trying to balance the ideals of the nation with the ideology of Marxism.

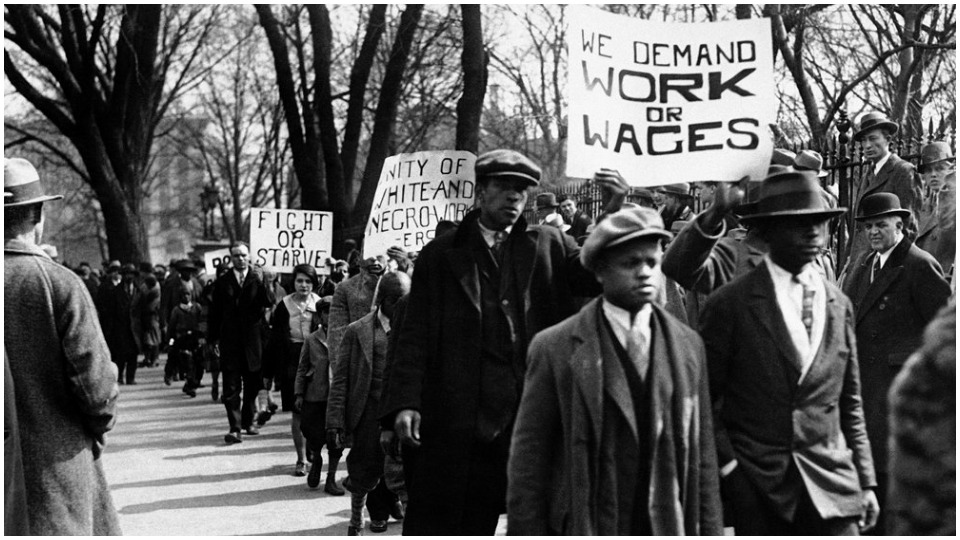

I refer to the “many worlds” of American Communism as the variances of experience displayed in the historiographical and biographical record in an effort to unpack how American Communism meant different things to different people, and most importantly that these meanings changed with people as the years went by. American Communist history is best understood as one component of a larger history encompassing a variety of radical political, labor, and civil rights movements dating back to the late 19th century; the history of Pan-Socialist Left in the United States. 3 By the 1930s, American Communism was indeed a “world political movement,” but it also existed as a domestic movement with localized influences that varied in experience from person-to-person. As a movement in the United States from the 1920s through the 1950s, American Communism varied from state-to-state, dependent upon geopolitical circumstances, social tensions over issues such as race, the extent of unemployment in dominant industries, and the palatability of industrial unionism within a given workforce.

Since the mid-1990s, scholarship on American Communism has expanded as newer sources became available, the Russian Center for the Preservation and Study of Documents of Recent History (RTsKhIDMII/RGAJPI) digitized its archives on the CPUSA, and new methods of interpreting history, such as an emphasis on personal experiences—sometimes referred to as social history—became more widely used. James Barrett’s William Z. Foster and the Tragedy of American Radicalism along with Randi Storch’s Red Chicago were among the first works to benefit from newer sources and demonstrated a clear break between the ‘traditional’ and ‘revisionist’ schools of thought, as put by Vernon L. Pedersen in The Communist Party in Maryland, 1919-57. The traditionalist school, best represented by Theodore Draper’s The Roots of American Communism and Harvey Klehr’s The Heyday of American Communism, viewed the ideological link between the CPUSA and the Soviet Union as the most significant aspect of this history, particularly when defining the boundaries of what made a particular strike, event, or organization “communist.” These historians depicted American Communism as a wholly unique phenomenon; so unique that to be a member of the CPUSA was to already be considered anti-American. Seeking to understand American communism as a domestic ideological movement, the revisionist school countered with an emphasis on the “correction of injustices in American society,” with works such as Mark Naison’s Communists in Harlem during the Depression and Robin Kelley’s Hammer and Hoe: Black Radicalism and the Communist Party of Alabama.4

The traditionalist school suffers from a general negative perspective of communist ideology and treats it as a foreign/alien movement that only existed because of the Soviet Union. The revisionists suffer from a nuanced and overly positive perspective and make very little effort to explain why such a history requires a methodology that emphasizes context both internationally and domestically. In turn, criticism of revisionist scholarship on the subject by traditionalist historians, particularly Draper’s essays in the mid-1980s, do not take into account how by 1985 younger history scholars were in the midst of transformative academic overlapping fields of study. Michael Brown identified some of these overlaps which contributed to a shift in how revisionist scholars approached American communist history as: anthropological studies concerned with links between power and social differentiation, a more critical understanding of “resistance” and “identity,” intersectional feminism and its focus on gender and the relationship of social norms to heterogeneity, and new sociological studies on the cultural dialectics of populist activism. Both schools, however, unveil an over-arching handicap that prevents the writers and readers of the subject from fully grasping the complexity of American Communism.

At the root of the traditionalist and revisionist schools of American Communist history is the placement of the CPUSA and its leadership class as the nucleus of the entire history; where the narrative both begins and ends as a political history of dissidents and radicals. This depiction convinces the reader that they are examining a fundamentally un-American concept; a history of radicals in America as opposed to a history of Americans who turned to radicalism. Both schools use the CPUSA as the nexus from which their conclusions are drawn: The CPUSA’s ideological link and involvement in the Comintern as well as the policies of the Soviet Union served as the foundation for traditionalist claim that American Communism was merely a front for Soviet espionage and subversive activities. The CPUSA’s promotion of African American, labor, and civil rights as a political policy served as a foundation for the revisionists rejecting the significance of traditionalist claims and focusing on the positive contributions of communists toward labor and social history. In both instances, the CPUSA is the beginning and the end of the narrative, while the externals are used as contextual links and exceptions to the rules. A prime example is the preferential use of the term “ex-Communist;” which according to Draper and Klehr does not express someone’s rejection of socialism and Marxist ideology but rather merely their former membership in the CPUSA. Additionally, the individual testimonies of low-ranking communists and communists with shared membership across various organizations are overlooked in most analyses. Rather than see leaders and ex-members of the CPUSA as the cohort of what communists were, the examination of ‘many worlds’ asserts that all participants, from leaders to rank-and-file activists to so-called ‘fellow travelers’, must be understood as involved in the movement to varying degrees in overlapping efforts, even if only some of their efforts are associated with the CPUSA.

The traditionalists focus on what I call the political world of American Communism; which indeed developed into a highly centralized political movement by the 1930s, with direct connections to the Soviet Union, centered on the CPUSA; but filtered out into other organizations such as the Communist League of America (CLA), the Workers’ Party of America (WPA), and later the Workers’ Party of the United States (WPUS). Little effort was made to understand the internationalist link; instead preferring to merely depict it as an act of subversion. The revisionists focus generally on one of two different worlds, the labor and community worlds of American Communism and also tend to generalize the distinctions between the two around issues such as racial equality in the workplace and at the community despite the fact that organizing for racial equality in the workplace was fundamentally different from organizing in the community. Randi Storch was among the first scholars to abandon the approach of a single narrative history by examining the social dimension of communist political culture during the Third Period (1928-1934) and utilized a geographical approach of focusing on Chicago. While not ignoring the overt ideological connection with the USSR, Storch demonstrated that amidst the early portion of the Great Depression, American communists both inside and outside the CPUSA “learned how to work with liberals and non-Communists” by developing “successful organizing tactics and fight[ing] for workers’ rights, racial equality, and unemployment relief.”5 Jacob Zumoff expanded on Storch’s approach in his work The Communist International and US Communism, 1919-1929, where he demonstrated that while the traditionalists were indeed correct in the overt connection between the Communist International (Comintern) and the CPUSA, they failed to address the nature of the relationship parties shared at the international level, such as how the Comintern emphasized that the CPUSA “Americanize” itself and act as a more independent political organization and did not ask of them to blindly follow the dictums of another communist party.

The division of American communist history into multiple narratives complicates the historiography and at the same time more accurately portrays the experiences of those who participated in the movement. Storch observed that the historiography had a few particular avenues; one which observes the political dimension of communist activity, one which examines the community-based organizations and localized communist activism for localized projects such as the Unemployment Councils, and one which observes the movement’s interconnection with other scholarship, such as labor and cultural studies.6 The concept of “many worlds” or “rival histories” is a common claim in the field of International Relations where “competition between the realist, liberal, and radical traditions” consistently reassess our understandings of social movements. International Relations scholar Stephen M. Walt argued this concept on a broad level when discussing the nature of international political ideology throughout the mid-to-late Cold War (1960-1991). In a subject where multiple interpretations exist in addition to multiple variances of experiences among sources, “no single approach can capture all the complexity” of a social and political movement. Furthermore, the end of the Soviet Union and the availability of new sources did little to resolve the struggle of competing theoretical interpretations of the history. Instead, it “merely launched a new series of debates” about the extent to which social movements were domestic in nature versus the by-product of international relations. For Walt, this was a matter about “contemporary world politics” using a variety of sources and contextual evidence to develop a well-rounded approach to policymaking.7

The notion of multiple worlds of a single movement also incorporates observations from world literature scholars about how “writers frame their respective cultures as ‘windows on the world.'” Daniel Simon asks, given the subjective nature of writing about international issues, “how do we read world literature?”8 This same question applies to almost any social/political movement at the domestic level: How do we read the histories of social/political movements that are invariably linked at the international level to various other cultures, movements, and people? The answer, whether conscious of it or not, is that we read it divided: When we want to understand American Communism as a political movement, we look to its international roots and its ideological links abroad; when we want to understand American communist activism in labor, we look to its temperament and palatability with specific working groups, such as industrial auto workers and non-white agricultural workers; when we desire to understand anticommunism, we look to the Cold War for contextual explanations for the violation of domestic constitutional rights. The particular ‘world’ focused on―labor, community, political―is invariably written with a subconscious emphasis of the specific circumstances of each case, but rarely do historians take the next step of linking these various worlds as multiple experiences of the same history; as subjective relationships to the same movement. Instead, each approach tends to emphasize itself as the history to be examined; be it the history of American Communism’s ideological roots in Europe, the history of the American labor movement and its tendency to utilize radical and militant communist organizers, or the history of individual American communist’s resistance to racial injustice and social inequality.

The history of American Communism must be understood through a lens that emphasizes the particulars of the society within which the movement existed; American society and the traditions as well as conflicts common to American people—both communist and non-communist. American Communism as a movement possessed a reach that extended into the political, the legal, and the civil corners of the United States during multiple transformative periods of American society. While both the revisionist and traditionalist schools of thought have added important contributions to this history, they have also both suffered from an approach that treats a multi-faceted social movement as a singular, monolithic phenomenon. Despite the depiction of acting as mere conduits between Soviet policy and American communist activism, grassroots rank-and-file communists in the United States channeled increased political energy into specific areas thought to be effective at, or at least open to, organizing for social change and typically sought only tacit approval from their local Party club. For example, by utilizing a geographical approach, Storch was capable of examining outside a framework that centered on the national CPUSA from 1928 to 1935 to demonstrate how “a wide variety of communists coexisted in Chicago,” including high and low ranking Stalinist cohorts and also non-Stalinist activists engaged in social, political, and labor-oriented activities. Additionally, both the break-away CLA and the CPUSA enjoyed the increasing romanticism and popularity of the Bolshevik Revolution among youthful activists, which by 1929 had “sparked the imagination of liberals and radicals throughout the United States.”9

Elements of the pan-Socialist tradition, which in urban areas like Chicago included “socialist, anarchist, and militant trade-union traditions,” rushed to engage with their society under an increased sense of urgency. The CLA and the CPUSA sought to gain momentum by seizing control of the increasing interest in revolutionary theory, Marxism, and the idealism of the Bolshevik Revolution by a newer and younger generation of scholars and activists.10 Under this context, it should be easy to understand that the term “American Communism” does not refer to exclusively one group, one organization, or one political party—as it has been used in the past. The tendency to view the movement as a “monolith,” where the degree to which someone is or is not a communist is measured by the degree to which they are separated or under the thumb of the CPUSA, dominates the existing scholarship on American Communism. It is important, however, to understand the subtle and theoretical differences of this movement if one is to understand the totality of its impact on American history.

The Communist International, or Comintern, played a role in the development of American Communism but it was not the sole actor as it did not have, and ultimately lacked the means of, direct influence over all communist organizations in the United States throughout the CPUSA’s heyday. Factional disputes and power struggles internally—themselves an inheritance of the first generation of communist party leaders from 1919 – 1921—contributed significantly to the redirection of local American communist politics during the Third Period (1928 – 1934). Although much of this factionalism was not alien to the Soviets and the Comintern, the acute and specific conditions of the factional disputes were linked to disputes about American labor traditions and conflicts with American political organizations, such as the Socialist Party. The CLA continued to operate throughout the Third Period, but its work focused on advancing “Left Opposition” to the CPUSA instead of pushing a general political policy for the United States. The CPUSA, in turn, resisted oppositional groups like the CLA as endemic of what they called “social fascism.”11 This dynamic forced the CPUSA to act politically and organizationally in ways the Comintern could never predict. Following the 1928 presidential campaign and the formal separation of anti-Soviet groups, the political agenda of the CPUSA “had neither a beginning nor an ending point,” as it sought to “register the extent of [the] Party’s support in the working class by mobilizing the maximum number to vote for candidates.”12 Throughout the Third Period, American Communism solidified into a social movement through the emergence of grassroots communist activism and the rise of multiple areas of strategic importance for communist work in the United States, areas that I call the many worlds of American Communism.

The primary sources chosen for my research are broad, and for good reason: to understand what American Communism was we must examine not just Party records and the memoirs of Party leaders but also the memories of the lived experiences of the movement across different geographic and socioeconomic backgrounds. The sources break up into two categories. First, there are the Party’s own documents and those archived by the Soviet Union; usually referred to as the Comintern Archives. During the Third Period, the primary means of distributing communist theory in the United States was through a wide variety of Comintern and CPUSA publications, such as The Communist, The Daily Worker, and its regional variants such as The Southern Worker and The Western Worker. For communists outside of the CPUSA, such as those that filled the ranks of the CLA and the SWP, periodicals such as The Militant served as the basis for discussion and followed a format similar to that of CPUSA publications. These publications were unabashedly anti-Soviet in their rhetoric and ultimately central to understanding how communists thought domestically about issues such as unemployment, race, gender, and the day-to-day struggles of working people during the Depression. As such, these resources are the best remaining examples of American communist thought throughout the late 1920s and 1930s and include theories both constrained by and liberated from Soviet oversight, as some of the sources extend from groups disassociated from the USSR.

Among the most significant and dominant publishers for communist literature for American communists were Progress Publishing, based out of Moscow, and International Publishers, based both in New York and Chicago. International Publishers Company started in 1924 in a joint-venture investment project started by A.A. Heller, a wealthy socialist who had ties to production industries in the Soviet Union. The publishing company struggled for over 15 years. At first, it was held up only by Heller’s overinvestment. It later gained a significant amount of support and cohort of dedicated readers from the Workers’ Party of America. The Workers’ Party of America later became the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) in 1927, but it helped Heller find outlets for the publisher to distribute. To compete with the publication of Marxist and communist works by other publishers, International Publishers focused on books “not yet published in English” but written by prominent socialist thinkers.13 Progress Publishers, based in Moscow, printed the various works of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and the Comintern’s theoretical journal, The Communist, in multiple languages for communist parties in Europe and the United States. Since most American communist political philosophy had its origins in the broad theoretical traditions published by both International Publishers and Progress Publishers, they can be seen as the lens through which the political, labor, and community communist activism evolved throughout the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

The next category of sources are personal memoirs, autobiographies, historical biographies, and oral histories. Part of this analysis accepts that party documents, government reports, and political newspapers present one interpretation of the historical narrative. But it also asserts that in between the depiction of events in official records and the memories of those events by people there exists some semblance of the truth. Autobiographies, like that of Peggy Dennis, provide insight into the way American communists thought about Party leaders and their experiences with Soviet policy decisions in the immediate aftermath of major political shifts. Similarly, autobiographies of grassroots communists, such as musician and chronic traveler Russell Brodine, do not focus exclusively on their identity as communists but rather incorporate their ideological experiences into their broader life experiences. The same case applies to the autobiography of the CPUSA’s oldest living member, Beatrice Lumpkin, who published Joy in the Struggle in 2015. Lumpkin’s work, like Brodine’s, uses her involvement in ideologically-motivated events as tangential and parallel to her overall life experience and thus provides a dynamic look into the life of a communist involved in multiple aspects of political, labor, and civic engagement. Personal memoirs, like George Charney’s A Long Journey, as well as historical biographies such as The Narrative of Hosea Hudson: Life as a Negro Communist in the South by Nell Irving Painter do a similar service of discussing communist activism as part of what these American radicals believed to be a component of their own personal and learned American ideals. Similarly, memoirs that focus exclusively on specific, chronological, and widely-known historical events, such as James Yate’s Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, help connect what grassroots communists believed to be patriotism to their ideological investment in socialism and Marxism.

Oral histories are continuing to serve historians as the ideal ways to understand what lived experiences mean to individuals still to this day. One of the most important aspects about oral histories of a movement such as American Communism is how they convey a tremendous gap between the average activist and the ideological world of politics. While possessing the fault of any primary source in terms of questionable validity, oral histories do possess a fundamentally unique trait: they are guaranteed to be real in the mind of the person telling their story. Over the course of eleven years my research has built upon over 10 oral histories of living and deceased American communists. Some of those interviewed remain active members of the CPUSA, others are part of political clubs in different parts of the country, and others prefer to remain anonymous for personal reasons. All of their stories, however, help fill in the gap of meaning for a movement that is told mostly through the lens of ideologically driven reports. In total, the sources used are intended to provide a broad examination of the American communist movement from multiple angles. The sources chosen for this research were picked because of their desire to tell their personal side of the story, and to explain why some individuals dedicated years, often decades, of their lives to a movement regardless of how the majority of the nation viewed them at any given time.

Outside of strictly industrial workspaces, individuals across the nation joined the American Communist movement for a wide range of reasons and from an even wider range of backgrounds. As a Jewish second-generation immigrant from New York City, Lumpkin spent years learning about the plight of workers from her leftist parents and family, as well as fellow community members, as the nation descended into the Depression. William Z. Foster joined after facing difficulty within AFL and syndicalist unions in the post-World War I strike wave. Danny Rubin joined after witnessing anti-Semitism in Philadelphia and linking the treatment of the local Jewish population with the general treatment of the working people in his city. Hosea Hudson joined the CPUSA in the wake of the Scottsboro case and the rising influence of the International Labor Defense (ILD) as an organization to fight discrimination. James Cannon, like many who eventually held leadership in either the CPUSA and/or other organizations such as the CLA, became inspired by the actions and tenacity of Russian Marxists to restore the “unfalsified Marxism in the international labor movement” and the romanticism of the Russian Revolution.14 Len DeCaux joined the CPUSA as a result of his perception of “herd impulses” he felt from teenage conformities while attending the Harrow School during World War I and the subsequent shortcomings of the IWW with regard to a practical plan to organize the masses. Russell Brodine joined after experiencing difficulties at his college’s local organization of fellow musicians in securing spots on the orchestra and defending against a cut of existing pay rates. In short, there never was a single particular reason as to why American communists became American communists—just like any political/social movement, American Communism attracted people by the message it delivered and the hopes it promised. The outlets for these citizens were the organizations previously mentioned and the subsequent labor and community organizations, such as the Unemployment Councils, the CIO, the ILD, and countless civic organizations that emerged out of the struggle.

While not exceptional by American political standards, the American communist movement was without-a-doubt one of the most diverse of all communist movements worldwide. The political idealists who crafted domestic communist policy in the United States under various organizations, clubs, and union locals faced a constituency with American values and American experiences, regardless of what their ideological schools of thought taught them. Either they, their parents, or their grandparents immigrated from Europe, or were liberated through emancipation subsequent to the American Civil War, to escape political and personal persecution. Many who came to publicly identify as communist during the ‘heyday’ of the movement viewed the tenants of socialism as compatible with or parallel to the virtues of American liberty, while others viewed the American system as a viable Republic merely corrupted by the special interests of an oligarchic elite. In this sense, American communists by the late 1920s were genuinely American first, and communist second. This is not to say that the majority of communists in the United States lacked a fundamental understanding of class analysis and awareness; but rather to suggest that the majority of American communists sought to relate their American experiences to their understandings of Marxism as opposed to use Marxism as a means to alter the social conditions of the United States. Furthermore, the diffusion of communists across various organizations masks the numbers of active communists throughout the Third Period and Popular Front, as noted by more recent scholarship. Many of the organizations and unions commanded by communists were not “numerically dominated” by members of the CPUSA, the CLA, or the SPA. The International Labor Defense (ILD), for example, operated as an independent organization of 2,520 individuals but was led and organized by a small group of 150 CPUSA members, and given a substantial amount of funding to operate in cities like Detroit and Chicago. Auxiliary organizations, which combined political members with union numbers and groups such as the ILD, “suggest a much wider support base than membership numbers allow.”15

Moving forward in the subject of American communist history requires a more radical departure from traditionalist narratives than provided by revisionist scholars. The approach of understanding the complexity of a movement through its “many worlds” of experiences is not merely a new historical account of the CPUSA; it is a history of a social movement of which the CPUSA is a significant part of. A critical analysis of American Communism must focus on the everyday, the grassroots. This approach is an attempt to create what Michael Brown described as necessary for the subject: a theoretical and methodological defense of what is legitimately unorthodox about traditionalist claims of American Communism. Rather than treat participants of a social movement as mere functionaries or as a component of a heterogeneous mass, this approach places participants at the front and center of the narrative. It also acknowledges the existing schools of scholarship on the subject as the product of an intellectual culture of all fields, not just tendencies in the discipline of history. Acknowledging the “many worlds” of American Communism is not just an acknowledgment of the complexity of the experiences of American communists, it is an acknowledgment of the complexity of all social movements—of which American Communism is one example of. It is only from that point that it becomes possible to expand upon such a method—critique it, develop it, modify it—thereby establishing some semblance of a history that is liberated from the contextual constraints of the high and low Cold War.