Renato Flores responds to Cam W’s argument for Maoism and the mass line.

Global warming is progressing. Millions are going hungry and do not know whether they can make the next rent payment. The houseless crisis is intensifying. We know we cannot just stand by, and we have to do something. But how do we do something, how do we slay the monster? How do we become free? It is not going to be easy. Everyone has ideas, some more or less thought out than others. What is clear is that we need a plan, and we need one fast, or the monster will devour us all.

In Cosmonaut, we wish to have an open forum for debate, where these ideas can be shared and discussed. Three contributions have been published, with responses, counter-responses and synthesis. This piece is meant as a (short) reply to Cam’s intervention on the debates around the party form started by Taylor B’s piece “Beginnings of Politics” and Donald Parkinson’s piece “Without a party we have nothing”. Cam’s intervention is heavily influenced by, and largely follows Joshua Moufawad-Paul’s (JMP) ideas on how Maoism has been historically defined, what problems it is responding to, and how it must be applied today. Cam’s main thesis is that Maoism, being the only ideology that has correctly absorbed the knowledge produced by the learning process of the Paris Commune and the Russian and Chinese revolutions is uniquely poised to provide an answer to the problem of the party. And that answer comes in the shape of the mass line, which is “a mechanism to transform the nature of the party into a revolutionary mass organization which can resist the neutralizing force of the party-form”.

I take issue with this last statement, and that is what I will try to elaborate on in this article. I start by agreeing with Cam that we must emphasize the points of both continuity and rupture of our revolutionary process. But I diverge from him in seeing the evolution of Marxism as something much more complicated than the picture drawn by JMP. Indeed, in 2020, the experiences of revolutionaries both in overthrowing the old state and in running a new revolutionary state can fill entire libraries. We know much more about what to do, and especially what not to do, than we did in Marx’s time. However, the process through which knowledge has been accumulated and synthesized cannot be reduced to a single path of advancement of the “science of revolution”. By doing this, we risk ossifying slogans, and allowing spontaneity to fill in the gaps, harming our organizing. The picture painted by Cam, which is inherited from JMP, suffers from the same problems Donald is replying to in his piece: a simple periodization is being imposed into a complex process of knowledge production. This periodization is then used to make a dubious point, namely that through an event a lesson was learned that marks the death of a paradigm and the birth of a new one. Everyone stuck in the previous paradigm is at best naive and at worst, unscientific. This is an extremely loaded word that produces a hierarchy of power: my theory is more powerful than yours because it is scientific. No burden of proof is necessary, because I am being scientific and you are not. I have successfully absorbed the lessons of history while you haven’t.

To begin to deconstruct the claim that Maoism is the highest paradigm of revolutionary science, we have to understand that one of the axioms on which it stands is flawed, namely that progress is linear and happens through a single path. Biology and evolution provide a practical counter-example. In a very simplified manner1, organisms face a problem, the environment, and try to find a solution through adaptation. Faced with similar environments, organisms will find similar solutions, even when they are in geographic isolation.2 This is called convergent evolution, and there are many examples in Nature. Bats and whales both evolved the ability to locate prey by echos as an adaptation to finding food in dark environments. Wings have been evolved by pterosauruses, birds and mammals separately. Silk production appeared separately in spiders, silkworms and silk moths. In a similar manner, some characteristics can be devolved. For example, some species of birds have lost the ability to fly after having gained it. It is not correct to view organisms as more evolved, as if evolution was something that accumulates.

In the same manner, progress in all branches of science is far from neat and linear. Geniuses have been forgotten or dismissed for centuries just to be rediscovered. Dead ends are often reached which require looking back into the past to reinvigorate theories that were previously thought dead. More importantly, co-discoveries happen, and happen often. Wallace and Darwin both came to the theory of evolution. Newton and Leibniz both developed calculus. In both of these cases, the co-inventors were resting on similar theoretical knowledge and facing similar questions. It is therefore unsurprising that they would come to the same solution. Even more, scientists working within very different paradigms, say like Mach and Boltzmann, were both able to contribute immensely to the field of physics despite working from vastly distinct starting points.

Going back to the revolutionary movement, our theory and our practice have been developed to surpass obstacles in our liberation. Even if these obstacles are not identical, they have been very similar. In the same manner as biological evolution, the science of revolution develops very similar solutions to address the problems revolutionaries face. We should expect that similar ideas will arise from similar contexts, a convergent evolution of tactics. From experience, the more scientists independently arrive at the same conclusion, the more likely that this conclusion is correct. In this context, Donald is correct to emphasize Lenin’s unoriginality. Like scientists, practitioners of revolutionary politics are faced with questions that they must answer, both before, during, and after seizing power. They learn from each other, and try to apply the common mindset to their local conditions.

If one revolutionary movement progresses and breaks new ground in the process to establish socialism, changes in the environment give rise to new problems that were previously not recognized. They might have seized power, but what now? As the Bolsheviks repeatedly pointed out, they thought building socialism was going to be easier than it actually was. Before the Russian revolution, Hilferding had stated that it would be enough to seize the ten largest banks to get to socialism. Hilferding, among others, believed that this was the great mistake of the Paris Commune, and if revolutionaries had just seized these banks, they would have been able to build a socialist system. But as we know, that was far from enough for the Bolsheviks. They did this, and much more. They were forced to continuously experiment, finding ways that could lead to socialism without losing the support of the peasants and workers. The lessons from Leninism cannot be simply reduced to the necessity of smashing the state: they are much more extensive and valuable than this.

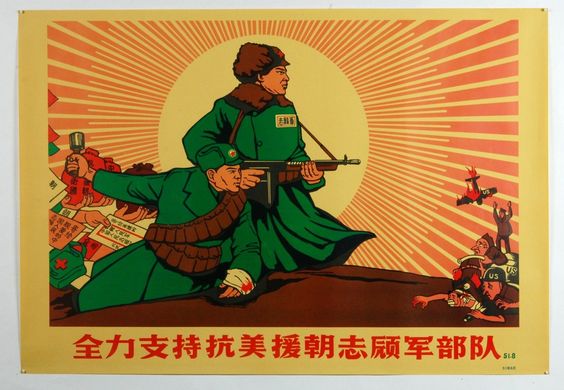

In the same vein, the Chinese Revolution was a gigantic experiment in emancipation that involved old and new questions, with old and new methods to answer them. And Mao diverged from Lenin in many aspects. Mao’s theory of change outlined in “On Contradiction” is quite different from Lenin’s understanding of dialectics. The Maoist theory of New Democracy also diverges from Lenin’s ideas of how a revolution should proceed. It is hard to answer if they are improvements or regressions. It is probably better to say that the Marxist canon was enriched by both thinkers.

Another example of returning to the Marxist canon and reevaluating or rediscovering old hypotheses can be seen in Kautsky, Lenin, Kwame Nkrumah’s theories of Imperialism. In his celebrated Imperialism, Lenin (rightfully) told Kautsky that the world was not heading towards an ultra-imperialist system where different imperial powers share the world peacefully—instead he argued that imperialist conflict was on the table. Indeed, Lenin was correct in that conjecture. World War I and World War II were both driven mainly by inter-imperial conflict.3 But after WW2, their differences would be sublated. A single capitalist superpower was able to set the rules on how the spoils would be divided. Nkrumah captured this in his Neo-Colonialism, basically rediscovering parts of Kautsky’s thesis and adapting them to the present. In this case, an exhausted paradigm was resurrected after significant adaptations were made.

You can see where I am going: it is impossible to lay out a simple evolution of knowledge for Marxism, with clean breaks from one another where knowledge only really had three leaps. Mao was correct in saying that socialism or communism was not permanent in the USSR and that a reversion to capitalism could happen, but he was surely not the only one to note the problems of socialist construction in the USSR. Revolutionary experience has been accumulated, and it has, for better or worse, been synthesized by revolutionaries. There are points where synthesizers like Lenin or Mao have made key contributions that have left a permanent imprint. Lenin was able to stabilize a revolutionary state, which allowed further problems of socialist construction to be posed. Mao was able to mobilize the masses against a stagnating party, which opened the problem of how to deal with class interests inside the party, and how to open a public sphere in a socialist state. Rather than having done science, it is probably better to think of them as having set up the stage for the further development of scientific socialism.

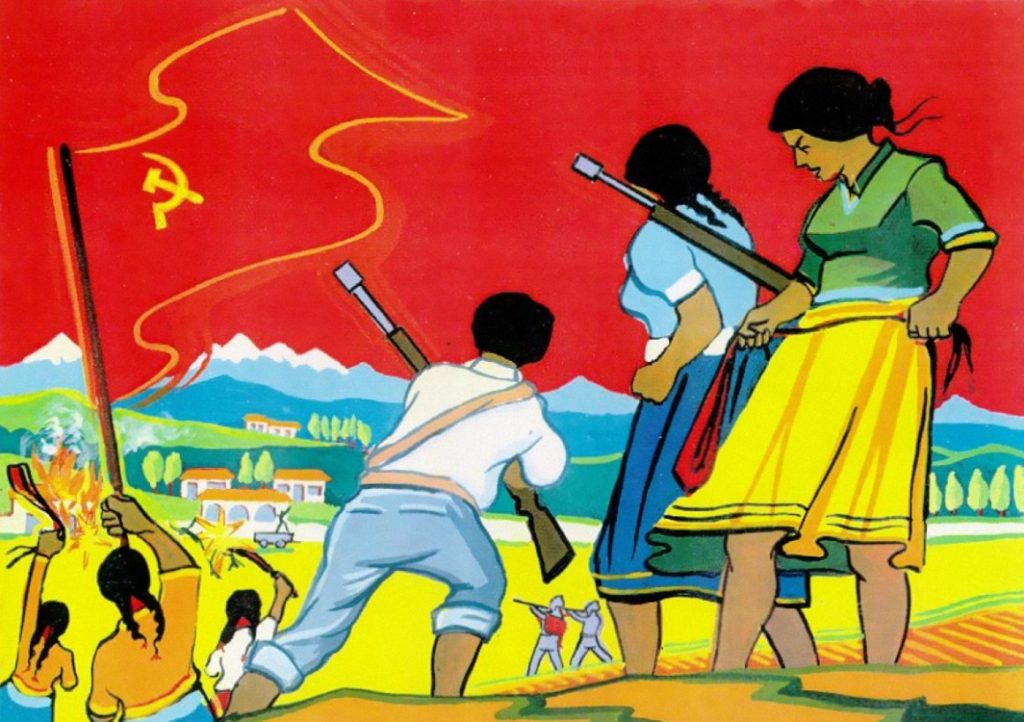

Whether Lenin and Mao were scientists or whether they set the stage for new science is a pedantic point— the important point is that periodizations of revolutionary science are not just meant to convey this, they are often used as discourses of power. When Stalin wrote “Foundations of Leninism”, “Trotskyism or Leninism”, or even the Short Course, he was not only trying to synthesize the knowledge gained from the construction of socialism in the USSR and set a roadmap for the future. It was an operation through which he declared himself to be the one true heir of Lenin and excluded others such as Trotsky or Bukharin. When the Indian Maoist Ajith wrote “Against Avakianism”, he was attempting to exclude Bob Avakian’s Revolutionary Communist Party from the mantle of Maoism. In the same way, JMP’s periodization is an attempt to claim for Maoism the mantle of the one science of revolution and exclude other Marxists from possibly contributing to this. But his claim ignores the complexity of knowledge development, something we have been addressing in this piece. Furthermore, even if one takes this periodization at its word, and we take Maoism to be a third synthesis, JMP’s periodization is not the only one in attempting to explain Mao’s epistemological breaks. Marxist-Leninists-Maoists—principally Maoists—who claim the legacy of the relatively successful Peruvian Shining Path, center Gonzalo’s theoretical contributions around People’s War in defining Maoism, rather than recognizing the Revolutionary International Movement (of which SP was a [critical] part) as the principal synthesizer of Maoism.4

More importantly, why is Maoism the only ideology that can claim to have absorbed the knowledge from revolutionary history? In terms of seizing power, or battling the state to a standstill, what have the Indian Naxalites achieved that has not been achieved by others, as for example by the Zapatistas who started from different premises5 yet face similar material conditions of indigenous dispossession? Are the Zapatistas somehow less scientific than the Naxalites? Or are they responding to different pressures of dependent capitalism in countries with backgrounds of settler-colonialism and casteism?6 Is there really nothing the titanic struggle of the African National Congress against apartheid can teach us, when the pitiful state of the ANC reminds us of how the Maoist revolution in Nepal has become increasingly coopted? What about the many other names of the long list of Latin American or African revolutionaries such as Amilcar Cabral or Paulo Freire, that are written out of this evolution? The successes and failures of the Arusha Declaration and Ujamaa or the Yugoslav experiment in self-management provide way more data points that enrich our knowledge, going way beyond the MLM straight line periodization that only really joins three points and attempts to exclude everyone else. In this spirit, it is worth noting that geographically diverse groups such as Matzpen in Israel and Race Traitor in the United States independently developed very similar ideas on what it means to be a race traitor, and how settler-colonialism and white privilege work to stabilize society.

Two-line struggles and “bourgeois” ideology

A periodization of history must be accompanied with explanations for the choices taken to divide one epoch from another. These divisions are usually used to give primacy to a political event or concept, after which one theory was proven absolutely correct and the other false. In the case of Taylor’s piece, he follows Badiou by stating that the Cultural Revolution showed that the party-form was an exhausted concept and brought forward the idea that new forms of organization must supplant it. In the case of Cam, who follows JMP’s periodization of MLM, the cultural revolution brings to the forefront the importance of the ‘two-line’ struggle and the mass line. Essentially, Mao reached a breakthrough realization: the ideological struggle between proletariat and bourgeoisie continued in socialism, and (a part of it) happened within the Communist party in the shape of a line-struggle. Stalin was wrong to declare that the USSR had achieved communism, and that this process could not be reversed. Indeed, capitalist roaders inside the party could reverse it and we have to struggle against them, and with the masses. A party which is properly embedded in the masses can successfully struggle against those who would reverse the revolution. And this is why Mao called for the Cultural Revolution: to rebuild those links between party and masses, and to battle the propagation of capitalist ideas in the party.

This framework is very appealing. It explains the restoration of capitalism in the USSR and China: the bourgeois wing of the party gained power because it was never defeated, despite the Cultural Revolution. It offers a simple and comforting answer to the question of socialist construction: just struggle hard enough against the capitalist roaders. It sounds a lot like a Manichean struggle for the world, and is especially well suited to an American mindset which is based on binaries. But while there definitely are undesirable elements within all Communist parties (just think of Yeltsin or Milosevic) the two-line struggle is a gross simplification that collapses all of the problems of revolutionary science into something that looks a lot like a magic trick: the masses will redeem us if we struggle with them. The whole problem of societal management, both politically and economically (which usually go together) is not a struggle between good and evil. It is the problem of how to control a totality, which risks becoming dysfunctional at places where faults happen, be it either improperly balanced alliances between classes such as the peasantry and the proletarians, existing monopolies on resources like technical skills, or sites of power which reproduce antisocial ideology. Mao was correct to identify some problems as originating from capitalist values and beliefs, which originate and are replicated from the existing conditions and require a cultural revolution to solve. But all of these problems cannot be all cast as bourgeois or capitalist, even if their sources come from constructing socialism on top of a capitalist society.7 By taking this simplification we risk allowing spontaneity to creep in in all places and hoping that high spirits will solve things for us.

There is an in-jest comment that asks: tell me which year you think the Russian Revolution was defeated and I will tell you which tendency you belong to. Was it with War Communism? Kronstadt? The disempowering of the Soviets? The retreats of NEP? Rapid and often brutal collectivization? The purges that destroyed the Old Bolsheviks? Kruschev’s or Kosygin’s reforms? Were Gorbachov’s efforts doomed already or did he make serious blunders along the way? Worse even, did he sell the USSR out for a slice of Pizza? The bitter truth is there is no simple answer to when the USSR was defeated. There was a long list of decisions that strengthened some groups while weakening others, eroded the revolution’s mass base of support, slowly created alienated groups of people who felt displaced from power, and eventually created a stagnated, even ossified, society. No longer able to progress toward socialism, it disintegrated under pressure. Until we digest that tough conclusion we risk searching for magic bullets to solve all our problems.

Seeking redemption through the masses is just one more illusion from a suitcase of quixotic tricks meant to bring us to socialism. Even if it is pointing at a real problem8, the solution is little more than a slogan. The careful and difficult balancing act of institutional design meant to construct a system that would, among many things, grant political freedom as to everyone, abolish permanent managerial roles by ensuring that “every cook can govern”, and eliminate existing oppressive systems carried over from capitalism, is reduced to making sure the proletarian line is upheld by “going to the masses”. This confuses tactic and strategy, and allows ossification and spontaneity to creep into all the missing spaces. Think about it for a minute. Some problems are easier to solve than others: if a local administrator is behaving badly and abusing their powers, we should discipline them through re-education or even removal. But what if they’re the only one in town that can actually run the irrigation systems? If they’re removed agricultural output will underperform or fail. If this administrator is reinstated, the masses, who are our ultimate allies, will feel betrayed. They didn’t fight a revolution for this. The administrator could feel justified in their privileges and try to go even further in their pursuit of even more privileges and power. But if they aren’t reinstated, the masses might go hungry due to crop failures, or freeze in the winter. Either way, they will be frustrated with the party.

These sorts of dilemmas around specialists and local administrators were a repeated problem in many societies attempting socialist construction, including the USSR and Maoist China. Mao sought a solution through the mass mobilization of the Cultural Revolution. The first stage dispersed the agglomeration of specialists in the city by sending them to the countryside. This was meant to break their privileges and urban strongholds, and (re)rally the support of the peasants for the revolution. The declassed specialists would then participate in the second and protracted struggle of breaking the monopolies on knowledge by educating the peasantry and opening rural schools. By ensuring that the peasants were able to administer their own affairs as a collective, they would not be beholden to a single, and potentially corrupt, expert. Mao’s solution was implemented at a scale never seen before, especially in a country of China’s size and its deep city-countryside divide., But Mao wasn’t the only one to come up with this sort of solution to the specialist problem: Che Guevara tried to enforce a smaller-scale cultural revolution in Cuba to persuade managers and specialists to throw in their lot with the revolution. Other revolutions came up with their own solutions: the Yugoslavs had a persistent problem with managers monopolizing knowledge and tried to solve it through factory schools and deepening education—without forcing existing specialists to undergo a cultural revolution. This did not end well.

Another more complicated problem was faced by the USSR repeatedly during its history: what happens when the lack of proper food procurement to the cities forces the party to choose between extracting food by force from the peasantry or making significant concessions to it, either through paying higher prices or devoting higher investments. Which of these solutions is ‘proletarian’? The USSR was forced to constantly oscillate between disciplining the peasants by force and granting them concessions because it could not solely rely on the stick or the carrot. Neither of these can be labeled more ‘proletarian’ than the other. Especially when contrasted with alternatives not taken, which can be regarded as capitalist, such as the full liberalization of rural China in the Deng era.

With this short digression, I hope to have laid out an important point: the working of a society is the working of a complex totality, where relations can become dysfunctional, threatening the whole. It is not (just) a matter of conducting line-struggles between “proletarian” and “bourgeois” lines. It is a matter of sitting down and diagnosing the system, understanding where the dysfunctions are, what groups they are serving or harming, and how the socialist construction can proceed by removing these dysfunctions. Politics is not a Manichean struggle. It is somewhere between a science and an art of organization. Compromises must be made, and we must constantly be asking how the power relationships in society will change if we are to undergo these changes.

The successive educational policies of the USSR in the 1920s, meant to both democratize knowledge and improve production, ended up empowering a new class of “red specialists” who would control the party 30 years later. The Yugoslav experiment tried to disempower the federal state and empower factory councils to devolve power to the workers, but ended up empowering factory managers and creating a comprador class that would trigger a Civil War. The agricultural reforms enacted by the Great Leap Forward meant to increase food production but ended up causing a food crisis. The type of historical analysis we need is a tough one, but being honest results in a better framing of things which goes beyond simply good and bad lines, and higher or lower scientific tendencies, or who betrayed what revolution.

Beyond the mass line: deciding how and where to struggle

The same framework, with some caveats, can be applied to formulate the principles of a revolutionary party. The party inserts itself in a capitalist society while simultaneously attempting to destabilize the capitalist totality and replace it with a new totality.

How do we begin to construct such an organism? Cam’s suggested plan of action is taken from JMP’s book Continuity and Rupture:

The participants in a revolutionary movement begin with a revolutionary theory, taken from the history of Marxism, that they plan to take to the masses. If they succeed in taking this theory to the masses, then they emerge from these masses transformed, pulling in their wake new cadre that will teach both them and their movement something more about revolution, and demonstrating that the moment of from is far more significant than the moment of to because it is the mechanism that permits the recognition of a revolutionary politics.

This poses several questions and problems, but the main thing is that we begin with participants in a revolutionary movement who are armed with theory that they take to the masses.

The first critique of this position is that the party is seen as some sort of external agent, formed by intellectuals, who have acquired knowledge and will bring it to the masses. It sets the party aside, as the unique interpreter of Marxism, and the object through which the people’s demands are translated to communist ones. It hopes that with the bringing of theory to the masses, the party will transform itself. We can contrast this approach to the merger theory. In 1903, Kautsky wrote:

In addition to this antagonism between the intellectual and the proletarian in sentiment, there is yet another antagonism. The intellectual, armed with the general education of our time, conceives himself as very superior to the proletarian. Even Engels writes of the scholarly mystification with which he approached workers in his youth. The intellectual finds it very easy to overlook in the proletarian his equal as a fellow fighter, at whose side in the combat he must take his place. Instead he sees in the proletarian the latter’s low level of intellectual development, which it is the intellectual’s task to raise. He sees in the worker not a comrade but a pupil. The intellectual clings to Lassalle’s aphorism on the bond between science and the proletariat, a bond which will raise society to a higher plane. As advocate of science, the intellectuals come to the workers not in order to co-operate with them as comrades, but as an especially friendly external force in society, offering them aid.

The difference between these two conceptions is that the first pays little to no attention to the self-organization of the masses and the ways they are already resisting capitalism. It asks us to go to the masses, without specifying which masses and how to talk to them. The second conception is that of the merger, where the intellectuals come to co-operate with the workers and see them as comrades, inserting themselves into existing struggles and amplifying them.

This difference is especially critical because it explains the way in which Maoists in the United States fill in their lack of clear tactics and strategy with spontaneity, leaving them lacking a clear plan, something they are slowly coming to realize. “Go to the masses” is left as a magic bullet. This raises the second problem: the identification of the “masses”. Cam suggests we start by “serving and interacting with the people”. A detailed study of the conditions of the people is a prerequisite of any revolutionary movement; just ask Lenin or Mao, but as with JMP, Cam grazes over the question of who the masses are that we are supposed to be interacting with in the United States. This is a question worth some reflecting on: the US is a unique creature in the history of the world. It is an advanced imperialist country, which leads to comparisons with Western Europe, but is also a settler-colonial society scaffolded by whiteness. It has a significant labor aristocracy who have much more to lose than their chains, and also has a significant surplus population that is easily replaceable and has little power to stop the monster.

Which groups are going to lead the revolution and which groups are expected to follow? How will hegemony over these groups be won? Essentially, who is the revolutionary subject in the United States? Who will bell the cat? Without making this explicit we run the risk of fetishizing the most oppressed subjects who unfortunately do not have the power to change the system.

It is important to remember that Marx located the revolutionary subject in the proletariat because (1) he studied the workers’ self-organization, how they had the power to stop accumulation if they wanted to, and what they were capable of achieving under adequate leadership and structure, and (2) the proletariat had less to lose from overthrowing the system because it possessed nothing. It could only lose their chains. But as we well know, the proletariat in the centers of capitalism failed to revolt. The Paris Commune, which so enthralled Marx, would move East, and the working class of the capitalist centers was pacified at best, or at worst enlisted in imperial or fascistic projects.

The cat would not be belled because some mice were getting good spoils. Starting with Lenin, there have been plenty of attempts to rationalize why there were no more large-scale revolts, like the Paris Commune, in the centers of capitalism. The labor aristocracy, understood as those who have more to lose than their chains, did not live up to Marx’s tasks. And if they are not willing to revolt and pick up the sword, who will then finish the job? This question is especially pressing in the United States, where capitalism is strongly racialized and where poor whites have been used to stabilize settler-colonialism for centuries. This is where the question of “who are the revolutionary masses” appears. Spontaneity fills in when the prescriptions are vague, which is why so many “mass line” organizations fall into a pattern of providing service aid, in the form of food or legal means, to the most oppressed in hope of activating them for the struggle. I do not wish to repeat a full critique of mutual aid that was already done in an excellent manner by Gus Breslauer. The two basic points are: people do mutual aid because it’s easy and makes us feel good, but in the end what we are doing is redistributing the labor fund and not threatening the state or the bosses in the process. Even if mutual aid can sometimes create useful auxiliaries, such as unemployed committees, they often cannot substitute for the main event. They also require massive amounts of energy and fund expenditures to keep alive, energy which could be spent more efficiently in amplifying existing struggles. We run the risk of burning resources and ourselves in doing something that does not center class struggle and is of minor use in fighting against the capitalist system.

It is important to locate this new fetish with mutual aid not only in the realization that people are suffering immensely but also in the failure of locating a revolutionary subject willing to fight to the bitter end. Mutual aid attempts to activate the most oppressed layers in the United States, but Marx’s other principle still holds: look for subjects that have the power to change society, rather than just the most oppressed. We should be looking at the sites of class struggle that are actually happening in today’s world and how these can be amplified to throw the capitalist totality into disarray. For this, we could start by reading studies of material conditions, such as Hunsinger & Eisenberg’s Mask Off, in great detail. An important place of struggle in the US right now are the struggles around social reproduction, specifically those around housing, childcare, and healthcare. Teachers’ and nurses’ unions, as well as the tenants movement, are in the front lines of struggle, and they are hurting capitalists because they are breaking into the capitalist totality in a way food distribution among the houseless is not.9

For some people, the natural starting place might be their union, especially if it is an active and fighting one. But for those who do not have that option, focusing on the tenants union movement allows us to connect to pre-existing struggles in the masses, amplify them, and understand their conditions in a very different way than food distribution does. Tenant unionism also provides us with targets that are actually defeatable, such as a local slumlord, which motivates our members, gives us publicity, and allows our organization to grow while further embedding it in the struggle. Other and larger targets can be tempting, but these are often heroic feats. The fight against Amazon, led by Amazonians United and other unions, is fighting an enemy at a scale much larger than what the proletariat is capable of organizing against right now. Their fight will be an extremely tough one, as the working class in the US (or even internationally) is still in a state of learning. Victories can be quickly stolen from us. For example, German workers defeated Amazon in Germany, so Amazon simply moved across the border to the Czech Republic, continuing distribution in Germany while avoiding their laws.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the introduction, we are in a seriously demoralizing moment. There is a rapidly changing conjuncture, where the pandemic and climate change fill us with urgency but make organizing hard due to increasingly scarce resources. We want to do something that is effective and brings liberation fast, but we are faced with the weight of the failures of the socialist movement, be it revolutionary or reformist. We want answers on how to do this and are attracted to things that do not sound that dissimilar to what we already know, or the ways in which our brains are programmed.

JMP’s style of Maoism is particularly well suited to the American mind. It provides relatively easy answers and provides enough silences that we can choose to interpret in ways that are not dissonant with our previous mindset. JMP also borrows plenty of epistemological concepts from American Pragmatist philosophy10, such as how truth is evaluated through practice, which makes it even more amenable to the underlying concept of science already present in US society. JMP writes well and clearly and is very articulate in his interviews. Because of this, it is not strange to see him becoming increasingly popular for a younger generation searching for these quick answers on what to do. This Maoism can also claim the mantle of the few revolutionary movements which are still vibrant today: the Philippines and India, which gives us something hopeful to root for internationally— something not as stale as defending an increasingly capitalist China.

However, to develop a proper science of revolution for the United States, whatever doctrine we decide to base ourselves, has to be heavily enriched with anti-colonial thought. One of the referents of Maoism, the Naxalites in India. have not properly dealt with Adivasi culture, and have sometimes misunderstood the way it operates, facing local resentment and resistance.11 This should raise a warning flag on the operating methods of the “mass line”, where the party is left as an interpreter because of its knowledge of Marxism. Furthermore, Naxalites have not successfully linked their struggle with the struggles in Indian cities. A strategy that bases itself on the most oppressed in the US would surely face similar problems. In this respect, the Phillipino Communists do this linking much better, through the use of broad quasi-popular fronts. However, they also went as far as endorsing support for Biden in the last US presidential election. How to adequately interface with the labor aristocracy and win hegemony over them is going to be a gigantic tactical and strategic problem here.

So to end, I am proposing we do not rely on slogans that can be ossified and filled in with spontaneity. We do not have a Yunnan to build a red base in the US, geography is not as favorable here. Our fight is a long one that will not be solved with tricks but will require years and decades of changing tactics and reevaluating strategies. In this spirit, Cosmonaut is an open forum where revolutionaries can talk to each other and propose ways forward. I know this contribution raises more questions than gives answers, but I hope it serves as a starting point for asking better questions.