In the second installment of the Internationalism series, Remi and Ahmed are joined by Bori, a South Korean student activist for a discussion of Korean history, the social dynamics underlying today’s political situation, the prospects for a left resurgence in RoK, and the elusive nature of South Korea’s much-maligned neighbor to the north and the unreality of reunification talks.

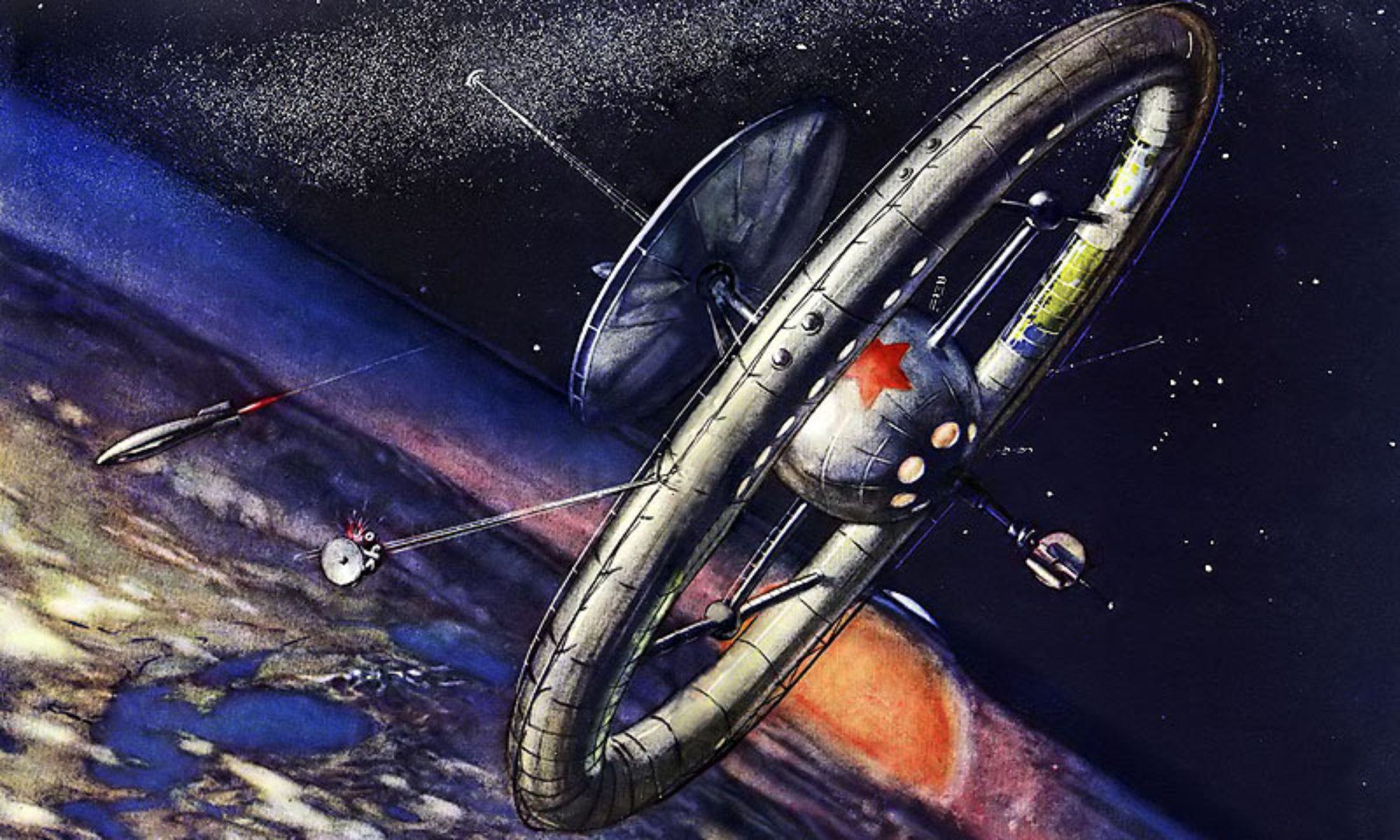

Terrestrial Shamanism against the Exterminist Leviathan

Renato Flores argues that a grand narrative is needed to unify and mobilize the exploited and oppressed against an exterminist world order.

I

The permanent news cycle paralyzes us. We wait in an anxious manner for the next push notification containing the latest breaking news item. It further spells our doom as a species. We share it on social media, screaming to the void that we are all doomed. We are validated. Tally up a few likes, regain some sanity, and wait for the next notification. International politics is predominantly reduced to a spectator sport and we can only watch in despair at how our side is losing: Bolivia, Corbyn, and the inaction on climate change after the Australian fires. Dreams of Fully Automated Luxury Communism (FALC) remain a fanciful hope for an earthly heaven, and not a practical political program. Instead, utopias are confronted by cruel reality. We are stuck on Spaceship Earth accelerating towards the dystopian future of exterminism outlined in the book Four Futures: neither the overcoming of scarcity nor the conquest of equality.1

Already, the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse appear lined up and ready to head the exterministic state: Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi and Johnson. But these four are far from the final product Capital needs to keep on going, and in some ways are just throwbacks to an older era. For example, Bolsonaro has received wide attention for his role promoting settler-colonialism in the Amazon. But in the Americas, accumulation by dispossession is centuries old and cannot be understood as a new phenomenon. The future state that Capital needs is darker. One that manages a society where there are not enough resources to go around, provided the economic and power structure stays the same. One where climate change and the limits of ecology mean capitalism cannot appropriate Cheap Nature to keep on reinventing itself.2 One where there is a population surplus that must be first pacified and eventually disposed of to ensure the stability of the system.

The combination of falling rates of profit, and a falling capacity to appropriate natural surpluses leads to surplus population. This concept was originally introduced by Marx, and is specific to an economic system. Because Cheap Nature is no longer as cheap, and production is overcapitalized, the wheels of capitalism are stalling. Within this framework, stating that there is a population surplus is simply reframing the fact that labor-power is being (over)produced in such quantities that capital cannot accomodate for a profitable use of it. The wage fund which would correspond to “normal” capitalist operation cannot pay the social reproduction costs. This means that the labor supply must be reduced, that is, the workers must be disposed of.

It is necessary to distinguish the concept of surplus population in an economic system from the Malthusian “overpopulation” argument that has been around for some time. The latter is a thinly-veiled racist red herring that basically states: (1) there are too many people on Earth; (2) we have gone beyond Earth’s carrying capacity, and (3) to return to sustainability we have to drastically reduce the population. This is often done by encouraging poor and racialized people to have less children. Because it is logically simple, distributes the blame equally among all of us, and does not challenge the power structure, it is repeatedly promoted and given intellectual currency. But this argument fails to acknowledge that most damage to the environment is done by a fraction of the world’s population. These people, who mainly reside within the imperial core, unsustainably enjoy what was best theorized by Brand and Wissen as the imperial mode of living.3 The imperial mode of living relies on “the unlimited appropriation of resources, a disproportionate claim to global and local ecosystem sinks, and cheap labor from elsewhere”. If this imperial mode of living were substituted with a more rational and ecologically sound system of food and commodity production, more than enough resources exist on Earth to provide a decent living for all.

With respect to surplus labor, the concept can bend in many directions. In a positive manner it promises freedom from toil. The automation utopians refer to “peak horse”, a real phenomenon: when cars were introduced, fewer horses were needed to draw carts around.4 Because of the declining demand for horse work, their population reached a peak in the early 20th century and declined after. The analogy is drawn to humans: it has become clear that the capitalist system cannot adequately employ large sections of the population, because these sections cannot contribute to profitability. In the global imperial centers, people remain underemployed in jobs which could perfectly be replaced by robots, or even eliminated. With this, the techno-utopians jump at the idea that advances in technology indicate that we have reached “peak humans” needed for production of essential commodities. Automation means that in the future we will need to work less. We will be in a post-scarcity society, and we will find a way of sharing the toils of labor adequately.

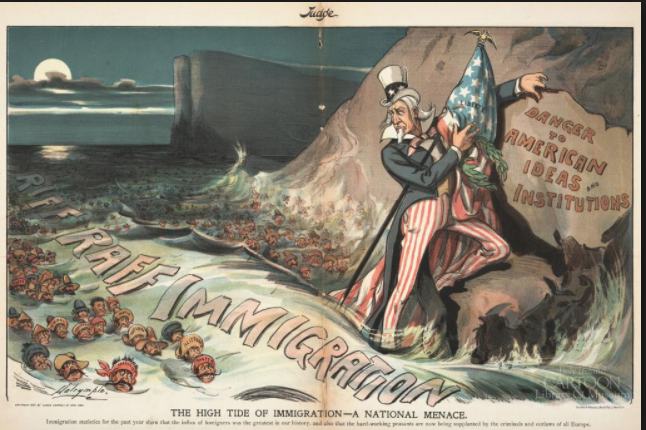

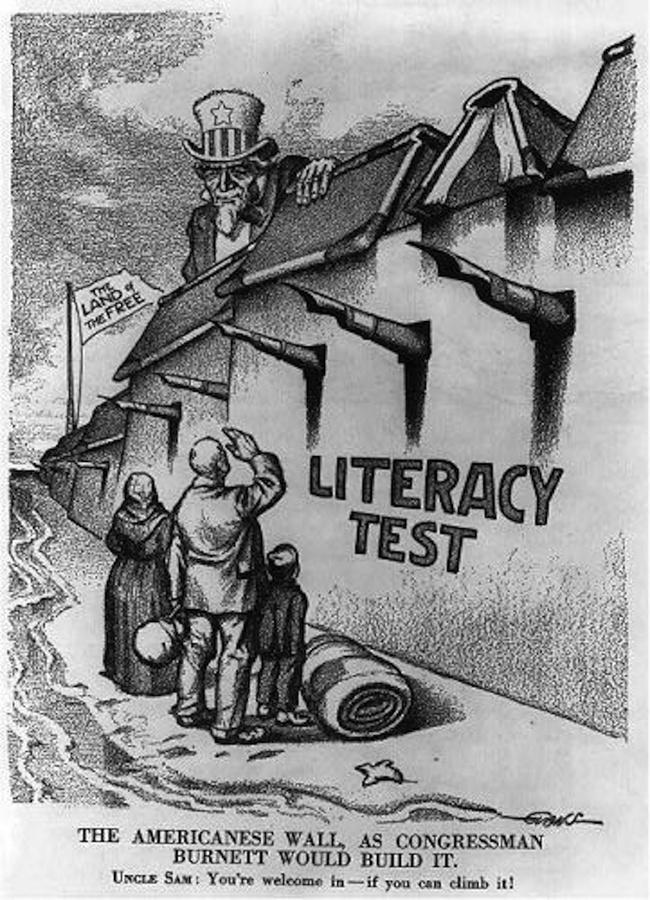

What the proponents of FALC fail to consider is that with automation, the surplus population might just as well be ignored or left to die. This is not a future designed by the Malthusian Thanos, the archvillain of the Avengers, who wanted to kill off half of the population selected at random. Instead, it will involve the isolation and elimination of the most vulnerable who no longer serve a purpose. The surplus population in the peripheries keeps on growing, becoming increasingly informalized and displaced from production, and at the same time forced to live in destitute housing, as Mike Davis studies in Planet of Slums. For millions of people, the costs of social reproduction aren’t being met, and they are either relying on the extended family and remittances from abroad, or simply waiting to die. On an individual basis, they can risk their lives to migrate towards the centers of capitalism. But the numbers are insufficient to provide structural relief. “Strong” borders make sure that the surplus population of the global South stays there, so transnational companies can reap the benefits of cheap labor.5

Instead of providing a fully automated future, the state returns to its basic skeleton of coercion and parasitism. And coercion can devolve into getting rid of the nuisance population that demands the means to live, but often has little to fight back with. There are several examples of this happening in history. The prime one is the recent fate of the Palestinians: in the 90s, due to the collapse of the USSR, a large number of Soviet Jews emigrated to Israel. They replaced the Palestinians at the lowest level of the Israeli class pyramid. This was very advantageous to Israeli capitalism, as it substituted cheap Palestinian labor, which had recently engaged in campaigns of civil resistance like strikes and boycotts, for more reliable workers. Palestinians were pushed out of the economy and slowly confined to their open-air prisons, which at the same time severely hurt their ability to engage in nonviolent campaigns.

An objection could be raised: Israel is not just a capitalist state, it is a settler-colonial state which attempts to erase Palestinians. Indeed, watching the working class in the Global North repeatedly vote to protect its privileges, it is tempting to adopt a “third-worldist” approach and deny that these classes are revolutionary at all, and that the potential for revolution lies in the Global South. However, these dynamics are barely contained to the centers of capitalism. Another current example is the role of Black people in Brazil. Brazil is similar to the United States in that it has a large black population directly descended from slaves. After emancipation, they were left in rural areas where opportunities did not abound. They chose to move towards the large cities (a Southward pattern in Brazil). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, their homes were demolished, and they were forced into neighborhoods full of informal housing: the favelas, which grew steadily during the 20th century. Their inhabitants often worked informal jobs, but as Brazil’s economic situation worsened, they were pushed out of the economy and into progressively worse jobs and even the criminal market. To deal with this, the police are increasingly empowered to indiscriminately enact violence, to deal with crime resulting from these transactions. In a racist society, this results in thousands killed at the hands of the police yearly.

So far, the picture painted does not differ much from the current situation in the United States, where police routinely kill people of color and walk away free. The murder of black councilwoman Marielle Franco is not that different from the murder of Black Lives Matter activists in the United States, if one sets aside the visibility of Marielle. But this would miss the point- more and more the quiet parts are said and acted out loud. Instead of Bolsonaro, who has his hands dirty in Marielle’s murder even if he denies it, we should be looking at another Brazilian politician. Rio governor Wilson Witzel was elected in 2018 on a platform of slaughtering “drug gangsters”. He has basically given carte blanche to the police to shoot on sight, and has proposed shutting down access completely to certain favelas. Witzel does this to wide applause, and it is not hard to imagine his reelection.

In the case of Brazil, racism comes into play, and is weaponized. But there are other examples of exterministic politicians who do not force themselves into office in the Global South, but are elected. One of the most infamous is Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte, who won the national election on a platform of slaughtering “drug-dealers”. Before jumping to the national stage, Duterte was the mayor of the city of Davao, and served seven terms. The emphasis here is placed on the fact that despite being known to command death squads, he was repeatedly re-elected as mayor. Later, he was promoted to the national stage, where he won a national election with 39% of the vote out of an 81% turnout. This is the barbarism which Rosa Luxemburg warned us about, with voters clearly electing barbarism. In the exterministic future which awaits us we will have more figures like Duterte and Witzel, who will openly shoot the increasing number of marginalized people to protect an ever decreasing community of the free who enthusiastically vote for them.

In the United States, the stage is set for something worse than Trump. Frank Rizzo, the police chief-turned-mayor of Philadelphia who supervised the MOVE bombing provides a historical example which was ultimately contained to just a mayoral position. The system produces many Rizzos, as a glance at any police “union” shows. Finding the cracks where stress will first concentrate in the US is not hard. Black and brown communities, both within the US and trying to access it will be prime cannon fodder. One just has to read history, or even the present news, to find that the list of affronts against them is long. However, the way the COVID-19 pandemic is being handled, and the inaction on climate change in the face of the fires in Australia, make it clear that the ruling classes do not care about any of us, and will do nothing to protect us from devastation if it inconveniences the death march of profit. The Climate Leviathan, an authoritarian planetary government led by a liberal consensus to adequately address climate change will never happen.6 The future where many Climate Behemoth states led by populist right-wingers, which simply refuse to deal with the structural problems of ecological destruction and population surplus, are much more likely. We are seeing this around the world, even in the centers of capitalism: rather than address the fires, the prime minister of Australia decided to outlaw climate boycotts. The time of monsters is coming.

II

Faced with this depressing prospect, how do we begin to organize? Postmodernism has repeatedly tried to kill grand narratives, while at the same time claiming the end of history has been reached. The underlying message was that class struggle is off the table. And it worked, for a while. But the house of cards is collapsing. The actually existing left is not prepared for the collapse of capitalism, often stuck in debates on theory that appear very important, but in practice make little difference in how they relate to the working class. Old-time socialists are disoriented as they face a working-class subjected to decades of ideological conditioning. They often forget that this is not the 20th century, and the same propaganda will not work.

We are missing both a unifying ethics of sacrifice and collectivity, and a sense of how merciless and brutal our enemies can be. Until this is regained, the confines of ideology channel rebellion into a simple solution- giving our powers to a terrestrial shaman, through the sacred ritual of the ballot box. The shaman knows how to interface between the world of the commoners and the sacred world of the political. He or she can lead us to salvation if we trust and follow his lead.

The shaman once again comes to ask us for our strength. We need to push him using all our might past the portal to take the sacred altar. Donations are requested, and we open our wallets. The most ardent canvass and phonebank to share the good news of “democratic socialism”. We study Salvador Allende and think, “well this time it could work, the US cannot coup itself?” And even if half the box of oranges is rotten, we believe that the bottom half must be good to eat. Once we get our shaman into office, he will be able to interface between the sacred and the common as long as we keep giving him our powers, delivering us to the utopia. Other kinds of shamans also draw from the collective, but our strength in numbers must be greater. We just need to show it in the ballot box.

But many cannot give their power through the ballot box ritual. And the other, darker shamans do not play fair. They control the tempo of the battle, and can cast their message across time and space much better. After all, the ruling class would rather have a dark shaman who doesn’t threaten its power than a red sorcerer who threatens capitalists profits. Our shaman plays by the rules of the game, and the most destructive weapons end up being unleashed by one side only. Even when backed by messianaic movements, Corbyn played fair, and lost. Sanders played fair in 2016, and also lost. Lula played fair, and was imprisoned to prevent his electoral candidacy. It remains to be seen what will become of the Sanders 2020 campaign, but the box of oranges is looking rotten. The dark shamans are able to weaponize our differences, to persuade others to give them powers. Our powers do not lie in the ballot box or within the constitutional framework at all. Until we achieve a grand narrative which not only includes all of us, the dispossessed, but speaks to all of us too, we are bound to lose again and again. Understanding this involves transcending the shamanistic and legalistic individual view to a collective, religious view of our historic mission of redemption and change.

I would be accused, fairly, of abusing the metaphor when describing the current state of politics. But narratives can be the best way to get a point across. We often make sense of the world around us with the use of metaphors and imaginary creatures. Our fears are often turned into monsters, and fear of monsters provokes hatred. The Right knows how to transform the Other into the monster: the Jew, the immigrant, the Muslim, the black, the LGBTQ… all of them ruining our society. They are deviants and criminals, and once we get rid of them, we will all be more prosperous. This narrative crystallizes a dominant group. It legitimizes the exterminist state, delineating the “us” from the “them”. It propels our bright leader to power not just through the gun but also through the ballot box. Because “they” are sabotaging us, we are not doing as well as we should. And when the left lacks the power to counter this monster-making with its own mythmaking, it can feel immobilized. Coexist stickers are not sufficient to unify a mass, and without a collective vision, as people like Elizabeth Warren are discovering, policy proposals amount to nothing.

We could try and play the same game of monsters. But the power of demonic imagery in the hands of the dispossessed is somewhat limited unless it is deployed as part of a wider struggle. At its minimum, it serves as a substitution used to relate to capitalism when it becomes something sublime and out of our control. In this disorientation, the structures of power are often reimagined through the imagery of monsters. This has a long history both in England and the Netherlands in the centuries of the ascendant bourgeoise, and has seen use in Haiti through the image of zombie-slaves.7 It is also present in contemporary Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, as each endures massive “structural adjustments” where the commons are privatized.8

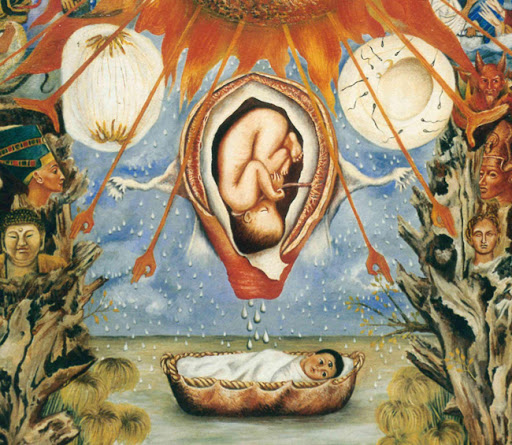

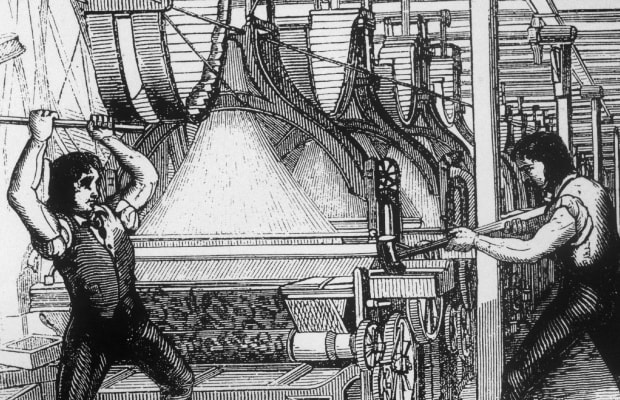

Monsters have served as valuable storytelling devices for progressives. Thomas Paine laid bare how the aristocracy was a cannibal system, in which aside from the first-born male everything else was discarded.9 In Frankenstein, the abilities of the new ruling class to lay claim to subaltern bodies and forming a monster provides a metaphor for the new factory system. Even before the Marxist analysis of capitalism, it was clear that the new proletariat of the nineteenth century was something historically distinct. The gothic, understood as the world of the desolate and macabre, was used to efficiently drive the political message home. It is not enough to understand something, dispossession must be felt. The warm strain of politics must be activated when the cold one is not enough, and as David McNally pointed out, they are still used in the Global South. While McNally focuses mainly on contemporary Sub-Saharan novels, he glances over the most effective present day example of this weaponizing: Sendero Luminoso’s use of the image of the pishtaco, a monster who would kill the children to rob them of their body fat so it could sell it in the market. Sendero was able to racialize the pishtaco as a white colonizer, and sow even more distrust of the Amerindians towards the white NGO workers. It was a key part of their Peruvian-flavoured Marxist story-telling.

At its best, Marxism with Gothic flavor appeals to the subconscious, making us feel the injustice, teaching us a primal instinct of repulsion to capitalism. It makes us gaze at the Monsters of the Market and understand that Capital lies behind them. Since his early correspondence with Ruge, Marx noted that he needed to “awaken the world from the dream of itself”. Marx’s Gothic imagery in Capital and the Eighteenth Brumaire was a way of telling the story of capitalism, and the conflict between bourgeoisie and proletariat, in a way that spoke to us directly, and mobilized us. The description of Capital as a vampire remains as memorable as ever.

Walter Benjamin took this much further.10 He wrote mainly in the interwar period- a time when psychoanalysis was a buzzword, and Lukacs had only recently published History and Class Consciousness in an attempt to link the subjective to the objective. It was also a time when the fascist monster was growing. Benjamin stressed the importance of imagery and revelation in bridging the gap between individuals and the collective understanding of capital. He brought insights from psychoanalysis into Marxism, and sought to break the hold of religion by means of what he called profane illumination– by intoxicating us with imagery to reach a revelation which inspires us. Heavily influenced by his Judaism, Benjamin sought out the historical memory for inspiration. By glancing at the Angelus Novus we understand that we must fight for the victims of Capital, to deliver a justice dedicated to their memory. In today’s world, we have no lack of sites to illuminate us: the lynching memorials; Standing Rock; the mass graves of the Paris communards or those of the Spanish Civil War; the river Rosa Luxemburg was thrown into; The Palace of La Moneda in Chile where Allende was murdered; the streets of the Soweto and Tlatelolco massacres; and of course the horrors of Auschwitz. The memory of the dispossessed stretches across time and space, waiting for justice.

III

Thomas Paine was not just trying to describe the kings as monsters, from which nothing could be expected except “miseries and crimes”.11 Paine also wrote, and attempted to put into practice, a political program for a better world. The formation of a mythology for the proletariat has been an integral part of the success of movements across the world. As Paine and Marx understood, gothicness is just the beginning. It gives us a way to tell a story which unveils the malice of our enemies, but we still require a positive force, a force of collectivity and millennialism to bring us together. Even the most mild form of leftist “othering”, the narrative of the 1%, presupposes the idea of a 99% that shares interests, and brings people together through their common dispossession.

Finding gaps in which Marxist ideology can be inserted has been one of the central research programs of Western Marxism. In essence, it articulates the Marxist view of the links between base and superstructure in a way that activates feelings, and the irrationality of being willing to suffer and die for a political program. The defeat of revolution in Western Europe came about from the strength of bourgeois ideology. It was able to perpetuate its hegemony. When the time came, there were not enough people willing to break their chains simultaneously. Many have written on this problem: Gramsci, Althusser and the Frankfurt School to name a few. After the Second World War, the golden age of capitalism provided a decent living for the working class in the centers of capitalism. Cultural critique or critiques of alienation were not enough to break the hold of the capitalist cultural hegemony. It could serve to identify weak points in societal cohesion, but it was never enough to inspire and guide a revolution. The Frankfurt School is an example of how critical theory can be divorced from practice when it is not grounded in class struggle.

Liberation theology provides a counterpoint of what is possible when class struggle advances ideology even within a reactionary institution like the Catholic Church. Taking inspiration from the Bible, religious figures reinterpreted passages that warned about the idolatry of money. Priests articulated how capitalism does not match the underlying values of society, and so were able to speak in the language of the people without abandoning their faith. Liberation theology set alight the underlying tensions present in many countries, and was particularly effective in mobilizing people in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Brazil. It was only defeated by an unholy combination of the Vatican and US imperialism, and has been replaced by religious faiths with a counter-revolutionary ethos.

Today, pessimism is warranted. To the historical defeat in the centers of Capitalism, we must add the collapse of the Eastern Bloc as well as the century of Latin American tragedies, where only Venezuela and Cuba barely hang on. Under a deluge of ideology the masses have abandoned liberatory faiths and embraced anti-communist worldviews. Socialism in our lifetime appears impossible, and the totems of revolution we hold dear have changed. This generation no longer venerates Che the way previous generations did. Che was not just a martyr who gave up a comfortable life for the cause— he was also someone who won. In this time of darkness, the voluntarism of a Che Guevara, who not only demanded, but exemplified a new type of person, a person who could challenge the US empire with dozens of “Vietnams”, fades away.

For a short while some heroic victories happened: US imperialism was forced to retreat from Southeast Asia and Nicaragua by guerillas. But this did not last. Today we look to more tragic figures like Rosa Luxemburg, and celebrate her supposed penchant for the spontaneity of the masses. We wait for the unplanned revolution, forgetting that Rosa was a tireless party organizer. A symptom indicating that we do not know where to begin. Somehow mass demonstrations against Trump and other right-wing populists are supposed to lead to a revolution, even when their politics are at best confused and the protestors hardly united by a material base. Those who praise spontaneity forget that groundwork has to be patiently lain, and even the most simple strike action requires tight organization. It is a wild dream to think that a social media hashtag will lead to the toppling of extremely resilient structures.

IV

Culture changes rapidly. As E.P. Thompson relates in his Making of the English Working Class, the pre-revolutionary wave of the late 1700s took root mainly through two mechanisms: the establishment of the Correspondence Societies and the Dissenting churches. Unlike the French one, the second English revolution never took place as it faced a stronger ruling class. This ruling class acted to break these societies, and the story of the late 1790s culminates in the Despard execution of 1803. During the early 1800s, a counter-revolutionary culture war was also taking place. A new faith of poor and rich alike was disseminated, while serving the cultural hegemony of the ruling classes: Wesleyan Methodism. Encouraged and financed by the upper classes, it was a denomination that emphasized social order. This picture resembles the birth, growth and defeat of Liberation Theology in Latin America. The streets and mountains where Catholic priests would lay their lives are today full of the churches which have propelled extremist politicians to power in Colombia and Brazil.

But English history offers us hope. The counter-revolution did not last forever, it was only a temporary sleep. The misery which caused movements to arise remained. After the cultural counter-revolutionary offensive wore off, Methodist churches provided an individual locus for community outside the official sanctioned channels. This was not the high Anglican church but a rough community center. Methodism would breed Luddites and Painites within its ranks. It became a path through which other rebels would rise up the ranks and use their organizing skills and access to the community to launch new counter-hegemonic offences. Some Methodist preachers became preachers of class consciousness, and explained how the values laid out by the church were opposite to those of Capital. They became involved first in the Luddite movement, and later in the growing Trade Union movement, over which they came into conflict with the church hierarchy. Chartists and Trade Unionists alike benefited from the organizer school that was the Methodist Church.12

Providing places where the dispossessed can come together and find their commonality is of utmost importance to the present socialist movement. Working-class ideology must be produced and reproduced. The German and Austrian Social Democratic parties of the late 1800s and early 1900s understood this, and built schools, sports clubs and all sorts of facilities in proletarian neighborhoods, which laid down the foundations for their success. While we might stare at the proliferation of churches in the American continent, and see them as a lost cause, the material roots that gave origin to liberation theology and many other working-class movements like the Poor People’s Campaign of Martin Luther King Jr. are still there, and will not disappear anytime soon. These communities will surely undergo re-radicalization.

V

Shamans and totems provide an initial bridge to radicalizing people, because they break their social conditioning. But in the long run we cannot rely on the shamans because, even if they recognize that their power comes from us, we are tempted into the lie that without them we are nothing, and this gives them undue control over the movement. In fact, the opposite is true. They are nothing without us. Socialism is about collectivity, much more a religion than a magic. Magic is always a private thing, while religion relies on collective experience.

Today it is hard to ignore that religious feelings abound in the community that follows the terrestrial shamans. Bernie Sanders’ supporters do not care if the man is flawed, or if the odds are stacked against him. What matters is the process that brings them together towards political power. Their recipe is insufficient: the community needs to learn that their power lies not in their vote, but in their ability to stop the economy if they wish. By bringing people together in the same spaces, they are laying down the seeds for something bigger. The dispossessed need to realize that they already are bigger than the shaman who leads them. Shamanic movements suffer from the domination of a person. We can relate to this person, but he or she can have too much control over the movement and in crucial moments can initiate its downfall. Sendero Luminoso disintegrated after Abimael Guzman went from the invincible Inca Sun to a man behind bars. It was not their terrible treatment of other leftists within their territory, but the shattering of the shaman that ended them. We should ensure that a movement does not base itself on a leader but produces organic leadership. Otherwise tragedy awaits: Chavismo could survive Chavez because he actively trusted and followed the masses. Lula’s Sebastianism required the masses to follow instead of lead, which left the Brazilian Left disoriented and defeated, a situation that worsened after the personalist “Lula livre” demand was won.

The odds facing Lenin, Mao, Castro and Ho Chi Minh were never good. And the odds facing us today might be even worse. But by looking at history we can learn how they were able to unify, motivate and mobilize the people behind their program with grand narratives. These narratives are mixed and intertwined with religion, even if they are subconsciously secular versions of the prevailing faith. Demonstrating how the values of people do not correspond to the social system is a great weapon in the hands of organizers. Like Paulo Freire and Amilcar Cabral recognized, rearticulating and recreating our own culture is inherently revolutionary. The bridge to turn religions of the dispossessed into socialist movements is very buildable. In the West, Bloch understood this the best. In Latin America, Mariategui’s theorization surely had an influence on both liberation theology and Sendero Luminoso.

The history of revolution is plagued by millennialism. From those who died in the German Peasant War demanding omnia sunt communia during the Reformation, to the North Koreans inspired to fight against unthinkable odds by Juche, a thinly-concealed revolutionary Cheondoism13, religion serves as an inspiration. Any serious revolutionary should explore his local culture, and weaponize cultural cues to show the dispossessed how to stand together, and make us aware that we’re all in the same fight. Of course, not all cultures and icons are built the same: for example, American nationalism is hardly redeemable, tied as it is to white supremacy. But most icons are mixed, with Chavez’s reclamation of Bolivar as a positive example. Whatever the case, inspiration is needed to break social conditioning, reinstall a collective ethic, and defeat the exterminists.

This comes through understanding that the revolutionary fights for a terrestrial paradise, and makes the highest of wagers to do so. In today’s world, where religion remains the last relief of the masses, utopia and brotherhood blend in as a starting point. Religion has two sociological functions: integrating communities, and resisting change. The latter can be a double-edged sword, serving both a counter-revolutionary purpose and a revolutionary one, when people feel their entire livelihoods are being swept from underneath them. It is not strange to see that many revolutionary movements against accumulation by dispossession end up triggering religious feelings. There are many examples, from the earliest records of the new faiths sweeping Europe during the Reformation in the German Peasant War, to 17th century England, to more current examples across the world. It is hardly surprising that the hardest enemies of late-stage capitalism are indigenous people fighting for their lives. The rallying cry during the Standing Rock protests was to “kill the black snake”, the pipeline threatening water. The cosmovision in which water is life proved itself revolutionary when faced with settler-colonialism. It was armed to face the monsters of the market, and able to unify the dispossessed. We would be fools to ignore it.

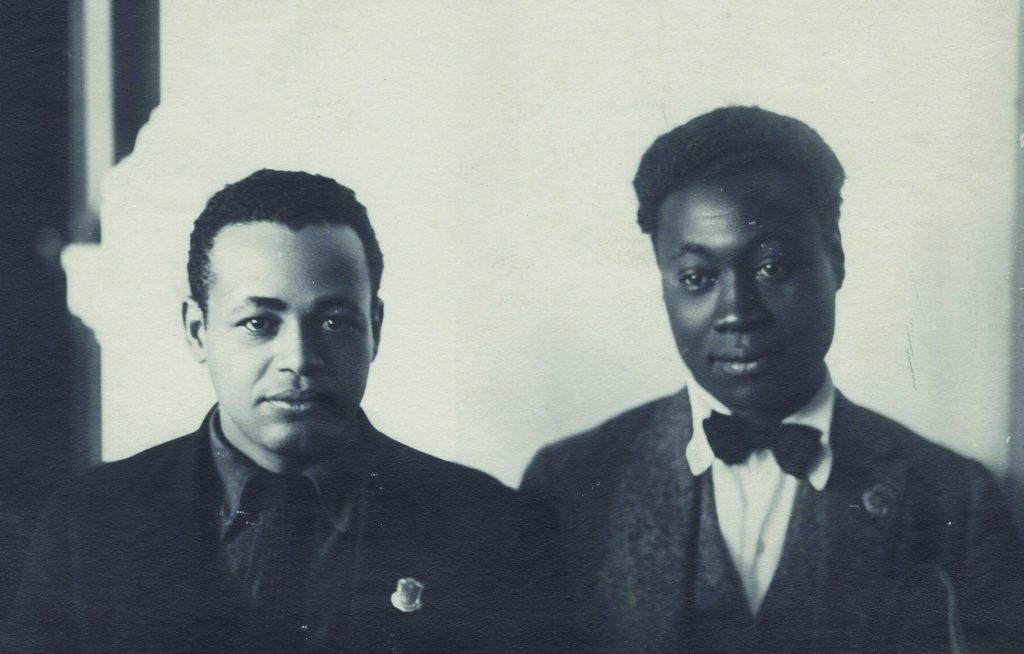

The African Blood Brotherhood and the Origins of Black Communism in the United States

Ian Szabo writes on the history of the African Blood Brotherhood as part of a broader tradition of black liberation that merged with International Communism after the Bolshevik Revolution.

From 1928 to 1934 the slogan “Self-determination for the Black Belt” became the core of the Communist Party of the United States’ (CPUSA) approach to Black Liberation. A common understanding among the non-Stalinist left of this strategy is that it was cooked up by Stalin in the late 1920s in order to purchase a positive image for his bureaucratization of the Communist International (Comintern) as he ascended to power.1 Because of this narrative, among many others, we are left in the communist movement with a false dichotomy between national liberation and social revolution, despite the reality that self-determination has always been a necessary part of the revolutionary transformation of society. Surrendering it to Stalinism betrays a fundamental basis of revolutionary Marxism rightly referenced by Lenin: “[to] not be a secretary of a tred-union but a people’s tribune who can respond to each and every manifestation of abuse of power and oppression[.]”2

Nothing exposes this false dichotomy between socialism and self-determination better than the history of black struggle and its relation to the US Communist movement. To fully grasp this history we must look at how black radicals developed a tradition of struggle on their own and merged it with the practice of international communism in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. This requires looking at the history of the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), the first Black Communist organization, as well as its founder Cyril Briggs.

Briggs hailed from the Caribbean island of Nevis where he had refused to abandon his heritage as a black man and integrate into society with his lighter-skinned complexion.3 Alongside many other native West Indians of the period, he immigrated to the United States, eventually Harlem, in 1905. Due to a stutter that prevented him from being able to speak fluidly with others, Briggs chose to focus on writing rather than organizing, becoming an intellectual and writing for the Amsterdam News in 1912. The particular event that sparked his transformation into a Marxist was in the period just before the October Revolution in 1917; Briggs was faced with the ugly reality that Woodrow Wilson’s call for all nations to have the right to self-determination was bankrupt, revealed by the execution of 13 black mutineer soldiers in Houston, Texas.4 Although the unveiling of Wilson’s Fourteen Points later on would cause Briggs to waver, his primary political orientation would be towards the Socialist Party; and despite the SP’s tendency towards a class-first politics that failed to fully comprehend the oppression of African Americans, Briggs would put forward the argument that for black people, “no race would be more greatly benefited by the triumph of Labor”.5

Briggs’ disillusionment with liberal insincerity and movement towards socialist politics was accompanied by the development of what would become known as the Black Belt Thesis. During his last months at the Amsterdam News Briggs would write an essay entitled: “Security of Life’ for Poles and Serbs- Why Not for Colored Americans”, where he put forward the idea of a “colored autonomous state” somewhere in the upper northwest or far west. He chose these regions because he believed they had not been as settled as most regions in North America. Although there are differences in terms of the region this model aimed to use, this shows that the idea of an autonomous African American nation within the American continent was not simply a project cooked up by Stalin in the late 1920s. Rather than a foreign product, the Black Belt began as an attempt by an African American socialist searching to synthesize the aspirations of the African liberation struggle from which he came with the politics of revolutionary Marxism.

Eventually, socialist politics and opposition to WW1 would put Briggs in conflict with editors of the Amsterdam News. At the same time Briggs was forging friendships with the likes of Otto Huiswood, Grace Campbell, Richard B. Moore, W.A. Domingo, Hubert Harrison, Claude Mckay, and other radicals in Harlem. It was from this milieu that the journal Crusader was born. The period following the October Revolution in the United States saw a great deal of confidence and energy in the American left, signified in part by the Crusader and the ABB. This energy combined the turmoil that broke out after WW1 with the re-alignment of the global socialist movement and the birth of the Comintern. Briggs would be the intellectual powerhouse of the Crusader, continuing his arguments for the benefits of uniting with the workers’ struggle, while also theoretically uniting the African diaspora’s desires for self-determination with the Comintern’s goal of a Socialist Co-operative Commonwealth.6 For Briggs, Black liberation did not necessarily require a communist vision, but it was the preferable grounds or stepping stone by which to achieve it. In order to understand why Briggs believed that the communist vision of national liberation was superior to Marcus Garvey and the UNIA, we have to take a look at the radical transformations that had occurred in the Comintern.

It cannot be understated how profoundly the formation of Third International widened the international character of the historical socialist movement, to which Briggs was responding. As Donald Parkinson has pointed out, “the Third International was an improvement of the Second. Marxists moved towards a truly internationalist universalism which saw the entire world as having agency in the revolutionary process and struggled politically against internal European chauvinism.”7 Taking direction from Nikolai Bukharin’s remarks on the subject, the resolutions put forward in the fourth congress of the Comintern cemented the point that the global communist movement had everything to gain through an alliance with oppressed people seeking national self-determination in the colonized world, as the task of the “[Comintern] on the national and colonial question must be based primarily on bringing together the proletariat and working classes of all nations and countries for the common revolutionary struggle.”8 This allowed Briggs and those around him to find a place they felt they did not have in the old socialist parties connected to the Second International, while also pulling them away from reactionary forms of nationalism that failed to properly deal with the nature of imperialism and colonialism.

At the same time that the Comintern was making strides towards a more forward-thinking international, Marcus Garvey was revealing his political commitments to reject socialism and even anti-racism. Already before the founding of the Crusader, W.A. Domingo had been fired from Garvey’s newspaper, Negro World, for espousing socialist politics. He would later become a collaborator with Briggs and co-found the Liberator with fellow ABB member, Richard B. Moore.9 According to Briggs in the foundational documents of the ABB, Garvey’s form of capitalist separatism would necessarily lead to the downfall of any attempt to gain self-determination, as inevitable capitalist crisis would wreck such attempts and sap morale from the liberation movement.10 A decade later, Briggs would more brutally relitigate this issue, pointing out that the Garvey movement failed to combat racism by ceding the American continent to white people, resulting in at least tacit collaboration with the Ku Klux Klan.11 In these criticisms, Briggs remained consistent with his argument that although socialism is not necessary for black for liberation, a socialist commonwealth on an international scale nevertheless provided the best chance for that task.

Although Theodore Draper characterized the ABB as being a typical iteration of the propagandist organizations of early century Harlem, it was equally familiar to the history of intellectualism in the worker’s movement, from Marx’s own Communist League to the circles the Bolsheviks emerged from.12 Of course, like any political organization it also had a program which formulated its basis on four points: “(1) the economic structure of the Struggle (not wholly economic, but nearly so); (2) that it is essential to know from whom our oppression comes… and to make common cause with all forces and movements working against our enemies; (3) that it is not necessary for Negroes to be able to endorse the program of these other movements before they can make common cause with them against the common enemy; (4) that the important thing about Soviet Russia… is… the outstanding fact that [it] is opposing the imperialist robbers who have partitioned our motherland and subjugated our kindred, and… [it] is feared by those imperialist nations.”13 The 1921 program fully articulated the class-based form of Black liberation Briggs sought to convey, utilizing the anti-imperialist commitments of the Comintern to build a bridge with the Bolshevik Party in Russia.

To fully grasp the historical importance of the ABB we must look not only to Briggs but to the entire membership. Drawn into the orbit of the ABB through her activism with the Committee on Urban Conditions among Negroes in Harlem, Grace Campbell was a social worker, court attendant, and prison officer convinced by the ABB’s call for socialism, black liberation, and decolonization.14 Alongside Hermina Dumont, Campbell was further radicalized by the international character of the communist movement. However, despite her involvement, the ABB was unfortunately an organization dominated by men, and so Campbell was relegated to secretarial tasks despite being on the “Supreme Council” of the ABB.15 Campbell dealt with the male chauvinism of the ABB through her involvement behind the scenes, as she held Supreme Council meetings and distributed the Crusader from her home.

According to McDuffie, Grace Campbell took the role of a mother figure for the ABB and much of the early communist left in Harlem. Not only a hub for the movement itself, Campbell’s home was open to anyone in need of food and shelter. It is true that this was a deeply gendered role to be given and taken up by Campbell, but the flipside of this is that it was also a source of power for a woman in the ABB able to “consciously construct and strategically perform this matronly persona to exert influence with women and to challenge the sexist agendas of black male leaders and to exercise influence in male-dominated political spaces”.16 Although much of this essay deals with the political orientation of the ABB, what is present in its history, as in most early socialist history, is a profoundly male-dominated dynamic which may be highly capable of dealing with the questions of decolonization and imperialism but fails to factor in, let alone fully integrate, the struggle of women workers.

A number of Grace Campbell’s comrades in her time as a socialist organizer would join her in Briggs’ ABB, but few would grow as close to Briggs himself as Richard B. Moore. A fellow radical from the Caribbean that found himself in Harlem, Moore came into Briggs’ orbit through his journalistic work and eventual founding of the Emancipator alongside W.A. Domingo.17 One point made by Moore himself about the ABB is worth keeping in mind: that although most of the history of the organization generally paints it as either a response to Marcus Garvey’s UNIA or a recruitment operation for the communist movement, this ignores the actual dynamics that produced the ABB. The reality is much more complicated, as many of the figures that made up the ABB had worked together prior to the organization’s formal founding. This means that the ABB was not necessarily a response to another organization but something which emerged from the intellectual and practical work black socialists had been committed to for years beforehand. Although many of these members certainly saw an ally in Leninism and the Comintern, their project had already developed its own political lines which the communist movement spoke to.

The campaign against Garveyism is a particular subject in which one can clearly see what Moore was getting at when he made this claim, as he did not fall in line with it. The aforementioned campaign was certainly in the right with regards to principled communist politics, but Moore refused to take part, preferring not to “[join] with the oppressors of your own people” and “betrayal of the right to speech.”18 As these debates were in the pre-Stalinized communist movement, the assumption that there needed to be a principled black united front with a right to criticism and free speech was prefigured within the movement and Moore’s conception of black socialist politics. If the ABB were simply made to respond to the UNIA or recruit black people to the communist movement, Moore would not have had any incentive to refuse to engage in this campaign, as it would have been perfectly consistent with the raison d’être of the organization. Instead, Moore’s response at the time was perfectly consistent with an organization that had always had its own agenda and vision of liberation.

In 1919-20, the ABB’s vision of liberation was encapsulated by a moment in Bogalusa, Louisiana, discussed by Moore in an article named after the city. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (UBCJ), International Union of Timber Workers (IUTW), and American Federation of Labor (AFL) had been organizing across racial lines in the city but were eventually attacked by an organization that synthesized both the redemption narrative and ethos of the Ku Klux Klan and the nationalism of the first red scare: the Self-Preservation and Loyalty League.19 Their target was the head of the union of African American sawmill workers and loggers, Sol Dacus, who would be saved by his shotgun-carrying white comrades, Stanley O’Rourke and J.P. Bouchillon. Gunfights broke out because of this, resulting in the deaths of O’Rourke and Bouchillon, alongside the president of the Central Trades and Labor Council Lem Williams and carpenter Thomas Gaines. Moore’s and Brigg’s own articles would have been known to the multi-racial workers of Bogalusa too, as they were avid readers of the Messenger and Crusader. After the killings, Moore’s article in the Messenger praised these men for having put lives on the line for their fellow black workers in his article “Bogalusa”:

Williams, Gaines, and Bouchillon have given their lives. O’Rourke imperilled his life, in the cause of true freedom. Not for white labor, not for black labor (though they died defending a [black worker]), nor yet for any race or nation, did they make the supreme sacrifice, but for Labor, that great university of fraternity of striving, suffering human-kind which though despoiled, despised, and rejected, alone holds promise for the emancipation of the race.20

This further demonstrates Moore’s argument that the ABB was a novel organization that neither responded to nor was subservient to another organization. Just as the theory of an autonomous African American nation was not cooked up by Stalin but a theory developed by Briggs, so too was the program of the ABB an expression of totally independent thinking of its members.

To further develop a rich image of the ABB we must look not only to understand its political dimensions, but also its cultural contributions. To do so we must look at another one of its members, the great poet Claude McKay. In the pages of the Liberator, Max Eastman’s newspaper, McKay would publish his seminal poem “If We Must Die” only two months after the founding of the African Blood Brotherhood, a poem which presented an explicitly revolutionary perspective which contained “no impotent whining… no prayers to the white man’s god, no mournful Jeremiad.”21

Shortly after its program was fleshed out and articulated, the ABB was integrated into the Communist Party. Earlier in May 1920, a convention was called among the various emergent communist parties that had not yet merged, the United Communist Party (UCP), Communist Party of America (CPA), and Communist Labor Party (CLP). The UCP had displayed a particular sensitivity to the question of Black liberation but the ABB remained officially distant due to the other parties’ lack of similar commitments. However, by 1921, Briggs would appear as a delegate for the ABB at the founding conference for the Workers Party of America (WPA) in 1921, later to become the Communist Party of the United States of America.25 Otto Huiswood became the head of the WPA’s “Negro Commission”, which was a good start for dealing with racial antagonism in the emerging party despite the persistent presence of neglect, and patronizing attitudes towards black members of the party.26

During this same period, the ABB experienced a bump in membership that forced it to choose between languishing in sectarian obscurity or fully integrating into the CP. A number of the leaders from Marcus Garvey’s UNIA had come on side to the ABB due to the former organization’s sketchy business practices, but these members were not particularly enthused with the idea of affiliating to the emerging Third International.27 To make things more difficult, the result of this growth convinced the ABB leadership to attempt a fundraiser for the creation of a new newspaper to named the Liberator, which not only failed to emerge but exhausted the continuation of the Crusader. With Briggs’ journal out of commission, he began working at the national office of the Friends of Soviet Russia in 1922, becoming an organizer at the Yorkville branch of the WPA, and managing to reclaim the name of his former journal in the form of the twice weekly Crusader News Service with the assistance of Grace Campbell.28 Although the UNIA continued to hemorrhage membership due to nonsense like bartering with the KKK, Briggs found himself unable to convince its membership to join the struggle for communism, and the ABB began to decline despite attempts to keep it afloat through sponsoring cooperative stores. By 1924, the ABB would become fully integrated within the WPA.

Ultimately, the ABB itself only existed for a short five years, but it left a huge impression on the American communist movement and its core membership would re-emerge in the nascent communist movement as the American Negro Labor Congress. Those who had built the ABB went on to become active organizers long after its demise, empowering African American workers throughout the southern United States. Their legacy is the idea that communism was, and still is, a vehicle towards self-determination and emancipation of all of the world’s oppressed. Solidarity of the entire international working class was at the core of their day to day political organizing, knowing that they could never be free so long as workers elsewhere were not.

Which Side Are You On?: The Challenge of the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution

The Ethiopian Revolution teaches modern leftists an important lesson about international solidarity, argues Ian Scott Horst.

Way back in 1848, the young Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels admonished in their Manifesto of the Communist Party, “Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things.” This basic prescription for political solidarity flows obviously and organically from the understanding of global political economy that they (and their ideological heirs) spent decades investigating, defining, and fighting for on street barricades. Marx and Engels diagnosed that the vast majority of the world’s population shared a mutual interest by virtue of its exploitation and oppression at the hands of a global class system, here in corrupt decay, there in bloody infancy. They suggested a liberatory class struggle as a path of resistance that was conveniently locked inside that global political and economic system and enabled by its own contradictions. To reject, indeed to overturn, that global system of exploitation and oppression of the vast majority of humanity by a tiny controlling minority of kings, political elites, and captains of industry, Marx and Engels prescribed not only moral outrage, but an understanding they called “scientific” of how those oppressed and exploited people could employ their vast majority in numbers and their strategic social relationship to the means of production to win the class struggle, and with it a better future for humankind based on cooperation and the communal good.

The phrase “Solidarity Forever” may have originated in radical trade unionism, but it was a damned effective compass for orienting one’s place in a combative world divided into potential comrades and bloodthirsty enemies. As leftist watchwords, the phrase reinforces an intuitive impulse growing out of the human experience of living and working together in a class-divided world, and neatly reinforces the deeper ideological explorations of theoreticians in the Marxist tradition. As a concept it rightfully suggests a deep connection between the daily struggles to survive, as experienced by the unpropertied classes and the political prescriptions of communist ideology. So why does it seem that so many of today’s heirs to Marxist tradition have discarded this time-proven compass when it comes to orienting themselves in today’s world of struggle? How did it happen that the first impulse of wide swathes of the Marxist left is to oppose the masses turning out into the world’s streets and avenues?

Leftists in the belly of the beast are morally (not to mention strategically) obligated to oppose the actions of our “own” imperialism. The dividing line this commitment creates is pretty easy to see in the separation of a “hard” left from a social-democratic one, even though the numbers of people identifying with either is much reduced in this post-Soviet century. But dialectical thinking should enable us to see that rejecting “our” government is actually not an automatic reason to express political support to every regime in conflict with the one we live under, and this is where much of today’s left seems to have stumbled away from the basic starting place located by Marx and Engels back in 1848.

It would be naive to suggest there are no differences in the mass popular mobilizations that have rocked the world’s streets in the last decade: The so-called Arab Spring and its stepchildren in Syria and Libya. Occupy Wall Street. Iran. Thailand. Zimbabwe. Venezuela. Nicaragua. The yellow vests of France. Hong Kong. But what unites these popular struggles is that, by degrees, much of the left reflexively rejected them out of hand, in some cases siding with the brutal police or military repression that would follow. Solidarity was discarded. In truth, some of these movements have had intensely reactionary elements, and in several cases that reactionary element is certainly at their core; but much of the left’s response was predictable, sudden, and utterly lacking in nuance, or importantly, any willingness to investigate the contradictory natures of these mass revolts or suffer any mild interest in the causes of mass grievance. The left has repeatedly rushed to identify the American CIA as the unquestionable locus of all global discontent. In several of these instances, the pretensions of the targets of mass resistance to some mantle of social progress were given greater credibility than the cries coming from the street. In many cases, the relationship of each country to the imperialist hegemon is factored larger than the class relationships within them. Let us not be naive: certainly, the CIA is engaged in subversion as a matter of routine. But what does it say about the possibilities for human liberation (and perhaps more importantly, about our abilities as professed revolutionaries to evangelize a universal message of revolt) that every spark of rebellion is reflexively dismissed? Put in another way, do “Black Lives Matter” only in the United States?

This phenomenon didn’t begin in the last decade. It really goes back to the halcyon days of left-talking military revolutionaries who dominated large swaths of the global South in the period between post-war decolonization and the fall of the Soviet bloc. With socialist revolution seemingly more distant than ever in the so-called liberal democracies of the global North, the left came to embrace many of these military figures with minimal critique or challenge, seemingly forgetting that printing up posters of Lenin isn’t quite the same thing as following his prescriptions for waging proletarian revolution or building socialism.

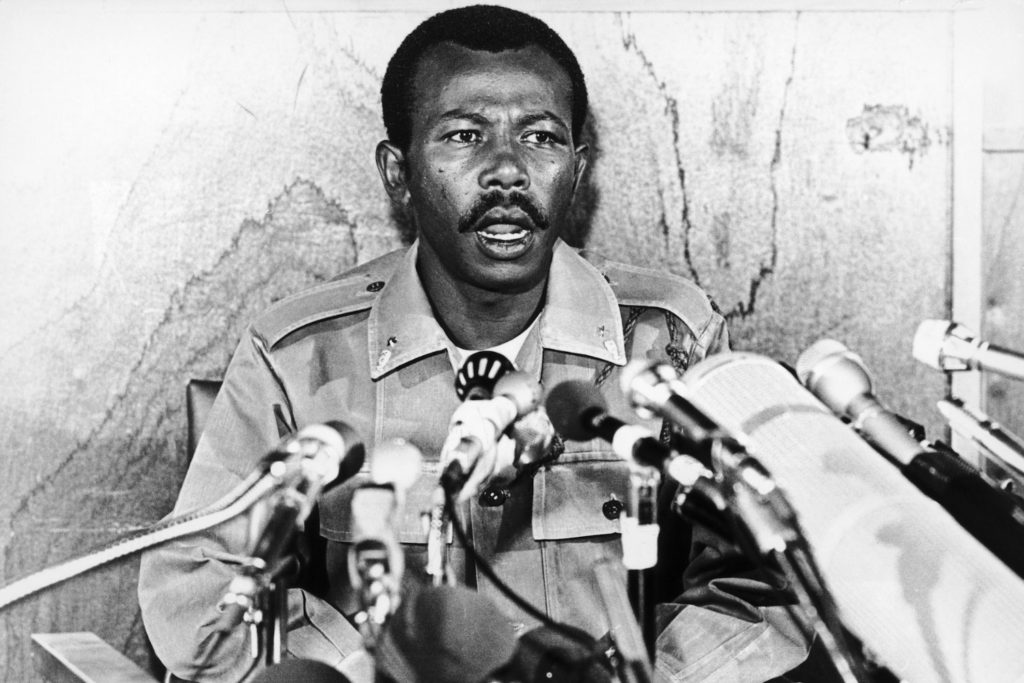

One of the clearer cases of this phenomenon — indeed one of the most tragic cases — was the embrace by much of the left of Lt. Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam and the military regime which ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991.

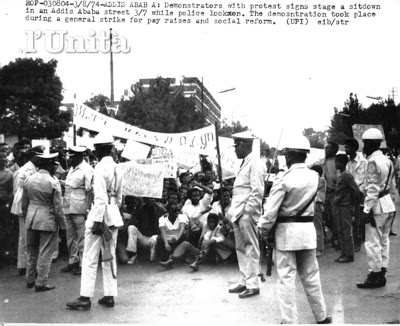

In February of 1974, a wave of labor strikes and mass protests swept the empire of Ethiopia. Tightly ruled by an aging Emperor Haile Selassie since the early decades of the century, now confronted with an increasingly harsh and vivid contrast between the haves and have-nots, the Ethiopian population stayed in the streets for weeks. They were soon joined by elements of the military which threatened a full-on mutiny. Taxi drivers, teachers, Ethiopia’s small industrial workforce led by what had been presumed to be a docile and captive trade union confederation in the pocket of the AFL-CIA, and most importantly, many thousands of dissatisfied high school and college students made economic and political demands, including that of popular democracy in the form of a people’s provisional government. There were mass demonstrations of priests and prostitutes, of minority Muslims; and the country’s vast peasantry began eyeing the land they worked in a variety of exploitative feudal land tenancy schemes. A country without political parties or press freedoms soon engendered a vibrant political culture in which underground publications written by communists soon dominated the national discourse.

In what has been described as a slow-motion coup, a committee of junior military officers known as the Derg began edging its way into the seat of power, forcing the autocrat to readjust his government repeatedly. They claimed that the spontaneous popular revolt needed direction and that the military was the only organized force in the country that could offer it. In September of 1974, the Derg pushed the emperor from power and shortly afterward proclaimed Ethiopia a state guided by “Ethiopian Socialism,” defined very loosely and not yet implying an imitation of, or connection to, the avowedly socialist countries of the Soviet bloc.

The new regime was ruled by a provisional military government, a triumvirate junta in which Mengistu was a junior partner. Mengistu had been trained in Fort Benning, Georgia, and displayed no apparent ideological sympathies. But ominously, in a year marked by remarkably little bloodshed, the Derg promptly executed sixty people, mostly prominent officials of the former regime and members of the nobility, but including a small number of leftists. In what was to set a pattern for government personnel changes in the Derg era, also killed was the head of the Derg himself, a liberal general named Aman Andom. While Mengistu remained a junior partner in the Derg, he was widely recognized as the agent of these executions. The military junta was now to be headed by another non-ideological figure, a brigadier general named Teferi Bente.

Over the next two years, the Derg government engaged in a number of revolutionary reforms, greeted with degrees of enthusiasm and skepticism by the revolutionary population. Some businesses were nationalized, but foreign and private investment was guaranteed. Feudal land tenancy was ended, but the land was turned over to the state, not the tiller. Students were sent to the countryside to evangelize Ethiopian socialism, but they, and the peasants they instructed, were punished for taking things too literally. The government tried to disband the independent labor movement and replace it with a captive state-run union that would focus on production and class peace. And all the while the regime continued the imperial wars against restive national minority populations, most notably the rebellious Eritreans in the country’s northern Red Sea region. The regime posed as anti-imperialist, but relied on U.S. aid, including all that military hardware being used against Eritrean peasants.

By the end of 1976, elements within the Derg lost patience with the quickly growing Ethiopian left which had continued its agitation for popular democracy and began to wage a brutal campaign of repression. This repression was met with violent resistance from the civilian left, which began its own urban guerrilla campaign against government officials guilty of acts of repression.

In February of 1977, Mengistu resolved some serious internal contradictions inside the regime with a preemptive coup d’etat, killing Teferi Bente and a handful of other officers of questionable loyalty. He immediately moved to make an alliance with the Soviet Union. He also unleashed what he would eventually christen as the “Red Terror,” a series of death squad campaigns against any and all civil opposition. While totals remain the subject of debate, the body count has been compared to that of the 1994 genocide in nearby Rwanda. By the time of the terror, the U.S.-trained Mengistu had become proficient at employing Marxist-Leninist rhetoric, and he claimed, invoking early Soviet history, that his purges were directed against counter-revolutionary “white terrorists,” which he defined variously as anarchists and Maoists as well as agents of imperialism and the former nobility.

When the quixotic and also avowedly Marxist-Leninist military leader of neighboring Somalia, Jaale Maxamed Siyaad Barre, invaded eastern Ethiopia and renounced his own Soviet sponsorship in favor of U.S. aid, Mengistu pleaded to Cuban leader Fidel Castro for assistance, and soon massive numbers of Cuban troops and Soviet bloc weapons flooded the country. Mengistu, with Soviet and Cuban aid, attempted to rally progressive global opinion against the Somali invasion, now marked as a proxy for imperialist meddling. Soon, Somali troops were driven out, and with massive donations of police surveillance technology from East Germany, the “Red Terror” found success by the end of 1978, wiping out all traces of opposition in the country’s urban areas.

A generation of political exiles fled the country, leaving behind a variety of guerrilla struggles polka-dotting the country’s rural expanses, one of which eventually snowballed into the rebellion that swept the regime from power in 1991. That rebellion also allowed the Eritrean rebels to consolidate their own victory and secede from Ethiopia. But in 1978 the future looked bright for Mengistu. He eventually built a captive state communist party (which he headed, of course), called the Workers Party of Ethiopia. Posters of himself, and Marx and Lenin were soon ubiquitous. Despite famine, economic disaster, and the occasional coup attempt, the regime lasted until about the same time as the Soviet bloc faltered. That global dust-plume of Soviet collapse undercut the stability of Soviet clients across the globe from Afghanistan to Benin, from Madagascar to South Yemen, from Kampuchea and Vietnam to Cuba; only the strongest survived and that did not include the Mengistu regime.

The great majority of the global left lauded Mengistu’s Ethiopia, accepting official government narrative as gospel. Socialist groups like the U.S. Workers World Party accepted state press junkets, interviewing regime members by day while nighttime neighborhood roundups left piles of bloody children’s bodies on street corners for the morning trash. Most Maoists and Trotskyists expressed degrees of critique, especially as regards the controlling influence of the USSR, and the global national liberation support movement anguished over the idea of the Cuban revolution suddenly in contradiction with the Eritrean national liberation struggle; but lasting orthodoxy seeping into 21st century leftist discourse holds that the Mengistu regime may have had its flaws, but it was another experience of Marxism-Leninism squelched by imperialism.

Most of the barebones narrative I have repeated above is not unlike the way much of the left recalls the Ethiopian Revolution in its totality, though perhaps I’ve been a bit more critical. They focus on the claims of the Mengistu and the Derg. They write off the dissent from the left. They are embarrassed by the violence, but since it was probably unreasonable infantile ultraleftists consciously or unconsciously acting in the interests of imperialism, it’s all well and good. As a model for socialism, well, it was a revolution from above, but it works that way sometimes.

As a verdict of history, let us be clear: an interpretation of Derg-era Ethiopia as actually socialist is completely shameful, and reflects miserably on the compass of solidarity used by the left. Nostalgia for Mengistu (still alive in a villa in Zimbabwe, by the way) is deeply and intensely misplaced. The global left embraced yet another left-talking military strongman, accepted his rhetorical claims at face value, and turned its back on what was one of the largest mass, civilian communist movements in African history. It’s worth remembering here one of the most useful axioms of Maoist praxis, “no investigation, no right to speak.” So let’s take a second look.

To really understand the Ethiopian revolution, one has to go back to at least 1960. While on one of his many foreign excursions, the emperor was briefly overthrown by military officers led by the Neway brothers. The rebellion was crushed and the Neways were executed, but it was a critical crack in the absolute rule of the emperor in a volatile period of continental decolonization. By 1965, a radical student movement formed the first of many clandestine organizations, the Crocodile Society, which organized demonstrations calling for “Land to the Tiller” and other democratic reforms. Against the backdrop of a growing world radicalization, resistance to the American aggression in Vietnam, the selfless albeit tragic guerrilla exploits of Che Guevara, the labor and student explosions of 1968, and the rise of a younger, more vibrant, New Left detached from Soviet orthodoxy, the Ethiopian student movement became the arena for revolutionary debate and discussion that was otherwise banned. Student publications were filled with nothing but theoretical articles debating the application of Marxism-Leninism to Ethiopia. This revolutionary student movement dominated academic culture in Ethiopia as well as among the many diaspora Ethiopians who were seeking higher education abroad.

The first Ethiopian left organization was formed secretly in France in 1968. Called Meison, the Amharic abbreviation for the All-Ethiopian Socialist Movement, it was the brainchild of an Ethiopian linguist named Haile Fida, who would become a notorious figure in the revolutionary era. The group had distinct views it argued for in the student diaspora, but as an organization, it remained completely clandestine until after the events of 1974. In 1969, a group of radical students led by Crocodile Society veteran Berhane Meskel Redda hijacked an airplane from Ethiopia to Sudan. They soon found themselves in revolutionary Algiers, were given a vacated pied noir villa by the Algerian government, and set up a base from which to coordinate revolutionary activities while they hobnobbed with Eldridge Cleaver and the Black Panthers and representatives of dozens of other global national liberation movements.

Things at home took a dark turn with the assassination at the end of the year of a popular student leader, Tilahun Gizaw, in what was presumed to be a government hit. A wave of repression killed many students, imprisoned more, and sent thousands of others abroad. Ethiopian student discourse took a serious turn: they knew a crisis was coming and with it the promise of a popular explosion, and they began to make plans to transform themselves from radical students to professional revolutionaries; they knew they needed a revolutionary party and started to plan how to build one. In 1972, they founded a second radical organization at a congress held in West Berlin, again in total secrecy. Calling itself the Ethiopian People’s Liberation Organization, its supporters were based everywhere there were Ethiopian students, from New York to Moscow, from Rome to Addis Ababa. It approached the most radical Palestinian organizations for military training, which it received. It competed for covert leadership of the movement with Meison, whose politics were not dissimilar but which had quite a different perspective. EPLO felt revolution was imminent, Meison prepared itself for a long march lasting many years.

It is true that the embryonic Ethiopian left did not lead the February 1974 uprising, though the ranks of people rising up included many young people who had spent their school years learning about revolution in the campus crucibles. Both Meison and EPLO immediately understood the importance of the moment, and most of their cadre who were based abroad returned home, where they began to publish and distribute regular underground newspapers and flyers. The most important of these was Democracia, published by EPLO, although that was, for the moment, left unsaid. They understood students couldn’t do it alone and they began to expand their social base. The revolutionary movement started to take off. It greeted the military coup with concern and suspicion; the welcome exit of the emperor tempered by the expectations about the predictable trajectory of a military regime. This was when the call for a people’s provisional government was formulated, at first supported by all factions on the left.

The left did not ignore the military. In Bolshevik fashion, they reached out to the military rank and file. EPLO even formed caucuses of revolutionary soldiers. Some oriented to various officers within the ruling military committee. Meison’s Haile Fida and one Senay Likke, a veteran of the diaspora student movement who had repeatedly clashed politically with partisans of EPLO, wound up becoming confidants of key Derg figures, including most importantly Mengistu, who was a veritable political tabula rasa packed with personal ambition. Shortly after some of the dramatic reforms announced by the regime, Meison dropped its calls for democracy in favor of cooperation with the military. Haile Fida and Senay Likke were soon referred to as the Derg’s politburo, and they and many of their followers were given portfolios in government ministries and charged with applying a socialist varnish to military rule.

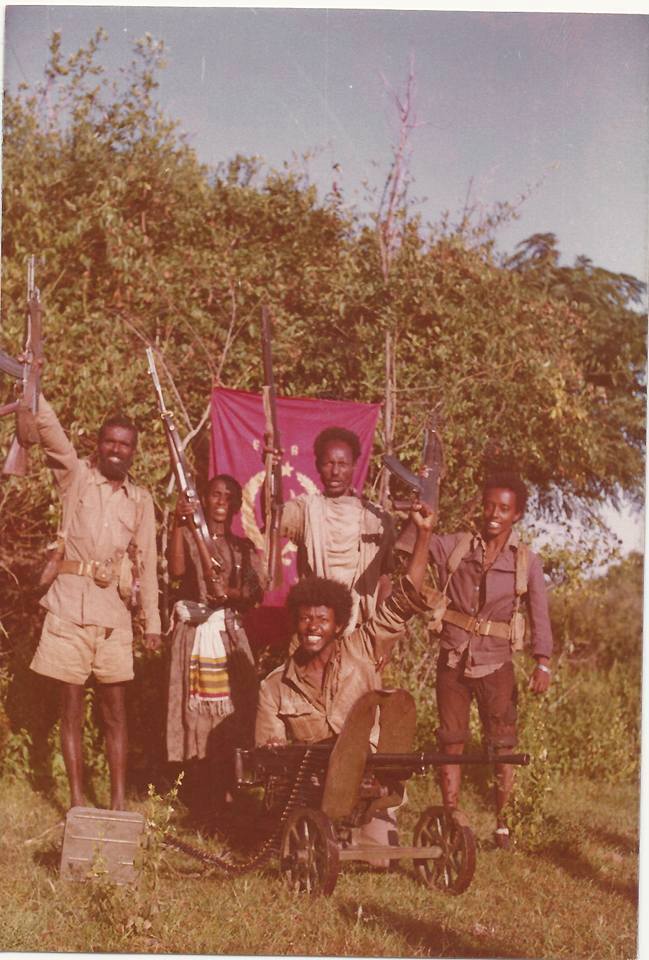

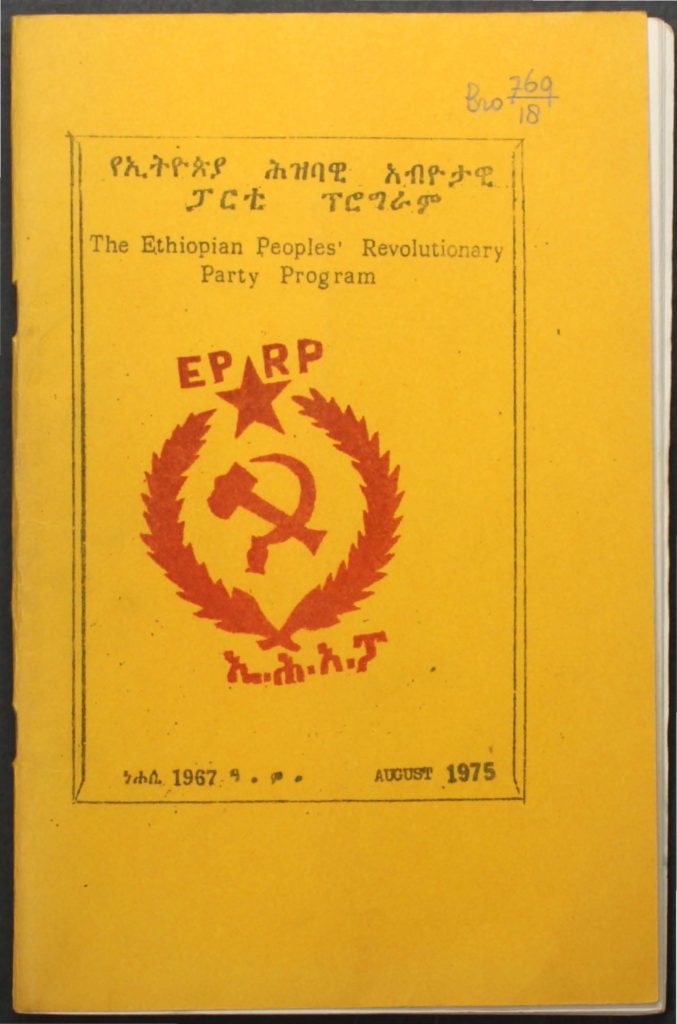

In 1975, EPLO transformed itself into Ethiopia’s first political party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party or EPRP. It had an elaborate nationwide network of clandestine cells and semi-open mass organizations. They established the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Youth League which attracted tens of thousands of eager revolutionary youth. They had a mass organization for women and their cadre kicked the CIA out of the Ethiopian labor movement. After that was suppressed, they formed their own red labor movement. They attempted, though ultimately unsuccessfully, to build an alliance with Eritrean rebels. At one point they were even accused of seizing control of national distribution of red chili pepper. At their height in 1976, they had thousands of members and tens of thousands more supporters and sympathizers. A rural base area in the north of the country was home to the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Army, which hoped to replicate the Chinese successes of waging people’s war and building peasant support in the countryside. EPRP has been called one of the largest communist parties ever seen on the African continent. It showed up to mass demonstrations with huge contingents carrying red flags, warning of the dangers of fascism from the regime and calling for the people to take power.

The politics of both EPRP and Meison started where one might expect for groups originating in the late 1960s: heavily influenced by Maoism, holding Che Guevara and the US Black Panthers in high regard. Meison tended more toward a kind of Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, but EPRP was ideologically quite iconoclastic. Its surviving propaganda materials reveal a commitment to revolutionary democracy and popular empowerment unparalleled in other left movements of the day. Surviving veterans of the movement talk of study groups where the reading lists may have started with Lenin and Mao, but ended with Frantz Fanon, new leftist economists like Huberman and Sweezy, and even Isaac Deutscher. Its ground-breaking 1975 program includes planks for workplace daycare to enable women to work and participate fully in society; it called for the recognition of the right to strike and laid forth a vision of a democratic society on a path to socialism. The EPRP’s formation threw off course the Derg’s own plans to form a political party; that didn’t fully materialize until 1984.

A comparison of how the EPRP organized for socialism with the way the Derg tried to impose it is stark. Again and again, Derg initiatives were clearly exercises in population control painted in red Marxist-Leninist language, devoid of popular empowerment but stressing obedience to “the revolution” and production. EPRP appeals called for the people to take what is theirs.

As Meison integrated into the state apparatus, simmering sectarian differences between the two groups became exacerbated. The EPRP accused Meison of compiling lists of its members to turn over to government agencies of repression, which were stocked with Meison supporters. The first person EPRP assassinated in reprisal for the government’s repression in late 1976 was a Meison cadre, a popular college professor, but one who was accused of having overseen a roundup of EPRP sympathizers.

1977 was a complicated year. Senay Likke lost his life collaterally during Mengistu’s coup. Meison eagerly participated in the first waves of “Red Terror” directed at the EPRP, but pulled back from supporting the government when Mengistu invited the Soviets in. Shortly before May Day, EPRYL youth preparing for celebrations were set upon by death squads and thousands were killed. During this period in general, the EPRP leadership was decimated. Its most important leaders were gunned down in the street; internal factionalism split the party, forcing Berhane Meskel off to the countryside to regroup and turning other factionalists into snitching enemies. Horrifying torture by the Derg including rape and genital mutilation was widespread. Parents were made to pay for the bullets used to execute their children.

When Meison broke from the regime, Haile Fida and its other leaders went underground. Meison lost its seat at the edge of power and joined the other victims of the terror. Thousands of its members and supporters were then killed or imprisoned, including Haile Fida himself. Ironically, both Berhane Meskel and Haile Fida were executed in the same prison in 1978, strangled by a graduating class of military cadets. Soviet advisors urged Mengistu to purge any traces of Maoism or Chinese influence, and so the last remnants of the civilian left were exterminated. By the end of the year EPRP was reduced to a struggling guerrilla force in the countryside; it survived through the end of the Derg era, but was banned by the new government. That, as they say, is another story; EPRP today calls itself social-democratic but it jettisoned the most radical Marxist parts of its program in the 1980s.

EPRP, Meison and the Derg all waved hammers and sickles. But an investigation of what they meant by those hammers and sickles reveals conflicting visions of socialism and a fundamental dishonesty on the part of the Derg. The Derg was always the creature of the military officer corps: it propounded a theory of the “men in uniform” meant to rationalize the role of the military as agents of social change. The Derg was not made up of the soldiers of the 1917-era Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies, it was the creature of Kornilov’s officer corps. Like the emperor before them, it repeatedly and openly said that the Ethiopian people were not ready for democracy. It acted out of expediency, not principle. The EPRP’s base included a layer of the urban petty bourgeoisie, but the Derg’s base included the massive layer of lumpenproletariat displaced from the countryside and crowding Ethiopia’s cities who could be counted on, sometimes mildly coerced, to turn out to pro-government rallies. But even with the transformation of the regime from a provisional one to a formalized single-party state over the course of the 1980s, military figures kept a tight grip, making up the majority of “Workers” Party membership.