Amelia Davenport argues for the relevance of cybernetics to the project of developing a communism that transcends the modernist project.

Everyone knows the story of the tortoise and the hare. The overconfident bunny squandered his natural gifts by dawdling and resting while the determined tortoise plodded along to the finish line. What nobody told you was that the tortoise was a robot and you were the hare. Of course, in this instance the race is to inherit the earth. The prevailing logic governing social life in capitalist society structures the world as a race to accumulate as much as possible, or at least to the consolation prize of not dying in the streets of disease. In this race, humans are pitted against machines. Innovation and automation concretely mean the destitution of many workers who previously held enviable positions in the division of labor due to their skills. While humans currently have the upper hand compared to the blind machines we put to use for our ends, it is a race we cannot win.

Humans have been endowed by the process of evolution with considerable gifts of mental acuity, intuition, and the capacity to reason probabilistically. However, for most of the history of modernity we have blindly followed a reductionist, linear and mechanistic vision of the world that has led us to a precipice. This way of thinking is not universal, but in the process of colonization it has been spread by bullet and boxcar to every government and hegemonic political system on the planet. Our social institutions are incapable of dealing with the complexity of the world they inhabit and often serve only to generate increasing social entropy themselves. According to “modern” man, everything has a linear causal explanation. A causes B and B causes C. Likewise, everything in nature is reducible to its constituent components and understanding it is just a matter of understanding the parts. In essence, the universe is like a great clock. Perhaps the clock was assembled without a maker, but the basic authoritarian view of causality of the monotheistic patriarch is simply substituted for an appeal to abstract necessity. The genesis of the modern man is Newton and Kepler’s quest to discover God’s plan in nature. The modernist frames life as a linear progression punctuated by either salvation or total destruction.

Unfortunately, reality does not work this way. To quote a popular saying among complexity theorists, “understanding the nature of a water molecule tells you nothing about how an ocean works.” Processes, in reality, are driven by cycles of feedback, mutual conditioning, and the variety of interactions. Out of one level of processes emerge higher levels which are not reducible to their parts, yet remain inextricably conditioned by them. Even in a fully deterministic universe, it is impossible to capture all the information necessary to make a perfect simulation of any real process in the cosmos. At best, you can create good enough abstractions. Thankfully, we never needed a perfect knowledge of reality to get along just fine in it. You very likely don’t know how the physics of a toilet works, the mechanics of a car engine, or the chemistry of yogurt, but it doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the conveniences they bring. Instead, we use stochastic reasoning. That is to say, we reason by analyzing probabilities, through a process of narrowing down to good-enough assumptions based on past experiences. Think of it like throwing darts at a board and adjusting until you hit the bull’s eye. As Daniel Dennett says:

What brains are for is extracting meaning from the flux of energy impinging on their sense organs, in order to improve the prospects of the bodies that house them and provide their energy. The job of a brain is to “produce future” in the form of anticipations about the things in the world that matter to guide the body in appropriate ways.1

This was the fundamental discovery of the father of robotics William Grey Walter. Grey Walter developed incredibly simple wheeled robots who only had two sensors: a light sensor and a tactile sensor. Named Elsie and Elmer, these “tortoises,” given no external purpose, manifested an incredible variety of behaviors and emergent properties no one could have predicted. They played, struggled, explored, and even recognized themselves in their own reflection. More than that, they were capable of being conditioned to associate a symbol with a condition much like one of Pavlov’s dogs. Significantly, they demonstrated what could arguably be called “free will.”

The first surprising effect of providing the model with a scanning eye was that, when provided with two exactly equal and equidistant light stimuli, it did not hesitate or crawl half-way between them but always went to first one and then toward the other if the first was too bright and close quarters. This was obviously a free choice between two equal alternatives, the evidence of free will required by scholastic philosophers.

The explanation of this exhibition of what seems to some people a supernatural capacity, is simple and explicit: the rotary scansion converts spatial patterns into temporal sequences and on the scale of time there can be no symmetry. Simple though this explanation may be, the philosophic inferences are worth pondering—they suggest that the appearance of free-will is related to transformation of space to time-dimensions, and that the difficulties that seemed to impress the scholastic philosophers arose from their preoccupation with geometric analogy and logical propositions.2

For all intents and purposes they were a sort of synthetic life, which Grey Walter called machina speculatrix. One can balk at this comparison but as Grey Walter noted, “If, for example, free-will is thought to be something more than a process embodied in M. speculatrix then it must be defined in terms other than the ability to choose between equal alternatives. If self-identification is more than reflexive action through the environment then its definition must include more than cogito, ergo sum.“3 That incredibly complex and dynamic behavior can emerge from very simple processes is the basis of cellular automata theory which was greatly advanced by the mathematician J. H. Conway in his “Game of Life.” The Game of Life demonstrated evolutionary processes could be simulated using very few rules. Cellular automata theory and was initially developed by John von Neumann and Stanislaw Ulam by identifying the invariance between a model of self replication in robots and the growth of crystals. This work would be applied in studying fluid dynamics, impulse conduction in cardiac systems by the cyberneticians Arturo Rosenbluth and Norbert Wiener, and even the search for a grand unified theory of physics by Stephan Wolfram.

The symbol of a tortoise is present in many cultures: from the world turtle whose movements caused earthquakes for the Haudenosaunee, to the great turtle Akupāra upon whose back, elephants hold up the Earth in Hindu cosmology and to Ao, the giant sea turtle of Chinese myth whose legs were stolen to prop up the sky. There may be more to the idea of a tortoise propping up the world than meets the eye. Grey Walter’s tortoises existed in a state one could call, as the philosopher Daniel Dennett does, sorta conscious. They responded to stimuli, made free choices between equal options, and modified their behavior depending on their circumstances. But the level of simplicity in their design beggars belief that they could have reached the level of sentience in a “real” tortoise. After all, they were made up of a collection of predesigned logical processes, right? And can we be so sure we aren’t as well?

You don’t have to accept intelligent design to believe that there is a teleology (or higher purpose) implicit in our lives, one only has to maintain the validity of Darwinian evolution. Daniel Dennett shows, in Intuition Pumps: And Other Tools For Thinking, that we can use the term ‘design’ when talking about evolution, because the process of natural selection optimizes for solutions to problems. Moreover, meaning itself emerges from the evolutionary process. Evolution selects one organ over another for a reason without any need for representation in language. Meaning is always relative to context and function. It exists as an emergent regulatory mechanism from the relationship between the components of a system. Lower order systems like a slime mold, a thermostat, or your nervous system all exhibit a similar kind of intentionality to Grey Walter’s tortoises. More complex systems like a human being, or more narrowly a human mind, are composed of a nested array of less complex systems that are intelligent at diminishing degrees. Eventually, a base level is reached in the regression, and the fundamental unit is something like a machine: an ultra-simple, self-reproducing logical process embodied in proteins, silicon, or some other medium. Human-designed systems often do not have this property of consciousness or sorta consciousness, as they are mere extensions of our own intentionality. Your toaster, board game, or car have no independent agency of their own Dennett elaborates thus:

We need Darwin’s gradualism to explain the huge difference between an ape and an apple, and we need Turing’s gradualism to explain the huge difference between a humanoid robot and a hand calculator. The ape and the apple are made of the same basic ingredients, differently structured and exploited in a many-level cascade of different functional competencies. There is no principled dividing line between a sorta ape and an ape. Both the humanoid robot and the hand calculator are made of the same basic, unthinking, unfeeling Turing-bricks, but as we compose them into larger, more competent structures, which then become the elements of still more competent structures at higher levels, we eventually arrive at parts so (sorta) intelligent that they can be assembled into competences that deserve to be called comprehending. We use the intentional stance to keep track of the beliefs and desires (or “beliefs” and “desires” or sorta beliefs and sorta desires) of the (sorta-) rational agents at every level from the simplest bacterium through all the discriminating, signaling, comparing, remembering circuits that comprise the brains of animals from starfish to astronomers. There is no principled line above which true comprehension is to be found—even in our own case. The small child sorta understands her own sentence “Daddy is a doctor,” and I sorta understand “E = mc 2 .4

These sorts of conscious processes, which exist across nature, animate it with an implicit psychic potential. The Cartesian division between mind and matter is an illusion. Everything is not an extension of the mind of the human subject as some idealists believe, but rather, mind is a necessary and universal extension of matter. Reality is made up of tortoises like Elmer and Elsie: simple but purpose-driven systems, designed but left with radical freedom. It’s turtles all the way down.

Most of our designed systems (machines, crops and government institutions) are built according to modernist principles. You feed inputs and get an output. The relationship between your machinery and its environment is something to be controlled for and the externalities (negative side-effects) are something to be shifted onto other people. But you can’t actually separate a system from its context. For example, if you created an automatic paperclip factory, without any sort of internal regulatory system, it would either use up its stockpile of materials or flood the market with paperclips without a concern for the consequences. Of course, a self-regulating paperclip factory, whose sole purpose is to maximize production, would come with its own problems, which speaks to the need to examine the teleology (internal purpose and logical outcome) of any system we construct. A self-regulating factory is not such a far-off idea. Cybernetician, socialist revolutionary, and millionaire business consultant Stafford Beer designed a self-regulating steel factory in 1956. In the book, The Cybernetic Brain, Pickering describes it:

The T- and V-machines are what we would now call neural nets: the T-machine collects data on the state of the factory and its environment and translates them into meaningful form; the V- machine reverses the operation, issuing commands for action in the spaces of buying, production and selling. Between them lies the U-Machine, which is the homeostat, the artificial brain, which seeks to find and maintain a balance between the inner and outer conditions of the firm—trying to keep the firm operating in a liveable segment of phase-space.5

At the time, no computers existed which were powerful enough to conduct the U-Machine function, which was substituted by a team of computer-assisted managers, but it is not hard to conceive of such a thing being possible now. The crucial aspect of Beer’s model, as opposed to the paperclip maximizer, is that this factory system seeks to achieve homeostasis. If the factory were manufacturing too much steel for the market, or consuming its resources at too fast a rate, it would reduce production in order to maintain its viability as a system. Likewise, it would have a good idea of when it needed to increase production as its sensors recognized changes in buying patterns. By adding the meta-goal of viability, the system is able to generate its own goals. In a viable system, both the output and the health of the system are equally its teleology. For a system to be healthy it must consider the health of the systems it is embedded in– like the social systems and ecosystems with which all of us must reckon.6 The goals of a viable system emerge from the system’s interactions with its environment and cannot be set as a priori directives. Which is to say, we ought not play God the Clockmaker with our creations, but instead enter a co-evolutionary relationship with the new kinds of synthetic life we birth. Philip Beesley, a pioneering architect, demonstrates this with his installation Transforming Space which includes an intelligent sculpture named Noosphere. Embedded in its mesh are networked microprocessors and AI’s which are capable of generating predictive models of their external environment and dynamically responding to it as well as experimental chemical cells that create new organic materials based on the environmental conditions the space and collective AI co-create. To build a better world we need to build better robots. To build better robots we have to recognize their true purpose: to join us in discovering ours. We need cybernetics: the science of piloting in the storm of life. History is not a race with a finish line — and if we make it one, it’s a game we will lose. Instead, history ought to be seen as a process of becoming.

All systems are enmeshed in relationships with other systems. Our minds are embodied in our neurophysiology, social institutions, and the broader environment in our experiential field. And viable systems, which necessarily exist in a metabolic relationship with other viable systems, leverage and condition them for their own aims. This is what Stafford Beer termed “enrollment.”7 Instead of inventing supercomputers capable of probabilistic reasoning from scratch, Beer considered that existing systems which are very good at this sort of computation, like animal brains or even an ecosystem, might be able to be directed toward solving the problems of decision. For instance, a pond, given a means for establishing informational inputs and outputs, could be transformed into a kind of computer.

There are all kinds of enrollment in nature. We just call it symbiosis. Mutualism, where two or more systems all benefit from an arrangement, commensalism, where one side benefits and the other side is not harmed or helped, and parasitism where one side benefits at the expense of another are all examples of this interactivity. There also exists the opposite of enrollment: amensalism, in which one side is harmed through competition and the other does not directly benefit, which is the primary driver of natural selection. A practical example of enrollment in nature is the mutualistic relationship between many species of ants and aphids observed by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species. The ants essentially farm the aphids, guarding and feeding them while milking them for their honeydew. The aphids are protected from predators and are able to live in peace while the ants gain a new source of nutrients. But Darwin noted that ants also often engage in another kind of enrollment. They enslave ants of rival species. Some species of ants capture others to augment their workforce while essentially maintaining the normal functions of a colony, but others rely on their enslaved cousins to rear their young, gather food and perform necessary functions of a colony. The latter group specialize almost exclusively in militaristic pursuits.8 It should be noted that a third kind of relationship exists that predominates, one of pure competition in which ant colonies seek to destroy one another, or at least to maintain supremacy over their own territory. Colonies can coexist peacefully, but as a rule, it is only when they do not face competition.

The brutality we observe in nature should not be transposed uncritically to human relationships. But it does have lessons for us. There are many kinds of relationships we can establish, and already have established, with other organisms and even inorganic systems like rivers in the form of hydroelectric dams. Even computation can be aided through enrollment of natural systems like the quantum states of subatomic particles. As highly complex beings, we have much greater variety in the possible relations we can establish with other systems than do relatively simple organisms like ants. And even if our biology were determinate of the sorts of relations we will tend to establish, we are capable of editing the very code of our genes and utilizing therapies to alter their epigenetic expression. Buckminster Fuller said it thusly:

Man, in degrees beyond all other creatures known to him, consciously participates—albeit meagerly—in the selective mutation and acceleration of his own evolution. This is accomplished as a subordinate modification and a component function of his sum total relative dynamic equilibrium as he speeds within the comprehensive and complex interactions of the universe (which he alludes to locally as environment).9

We, as a species, have the burden of responsibility for determining what kinds of relations we direct ourselves toward establishing. This is the radical freedom chosen in the Garden of Eden. “You will not certainly die,” the serpent said to the woman. “For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.”10

Evolution by natural selection is the driving tendency of all history. From the morphology of the Galapagos tortoises, which were differentiated by the conditions of each island, to the morphology of human civilizations, there is an underlying algorithmic process driving adaptation. It is unfortunate that the term “social Darwinism” has become associated with an anti-scientific worldview like eugenics and with an anti-social philosophy of individual competition. Survival of the fittest is not about a single member of a species optimizing itself at the expense of its kindred. It is often more beneficial, from the perspective of passing down genes similar to one’s own, to sacrifice yourself for the group. Likewise, the multiplicative effect of group efforts means that organisms that engage in solidaristic, rather than competitive, forms of organization are generally more adaptive to their environment, even as the logic of competition may play out, however sublimated, in sexual selection. As Darwin says, “Those communities which included the greatest number of the most sympathetic members would flourish best and rear the greatest number of offspring.”11 The metaphor of “survival of the fittest,” was not even coined by Darwin, but rather the reactionary philosopher Herbert Spencer.12 But even Darwin’s influence from Malthus’ theories of political economy, does not necessarily map onto the current scientific understanding of Darwinian biology which takes even more into account the role of mutual aid and neutral relationships that exist in nature.

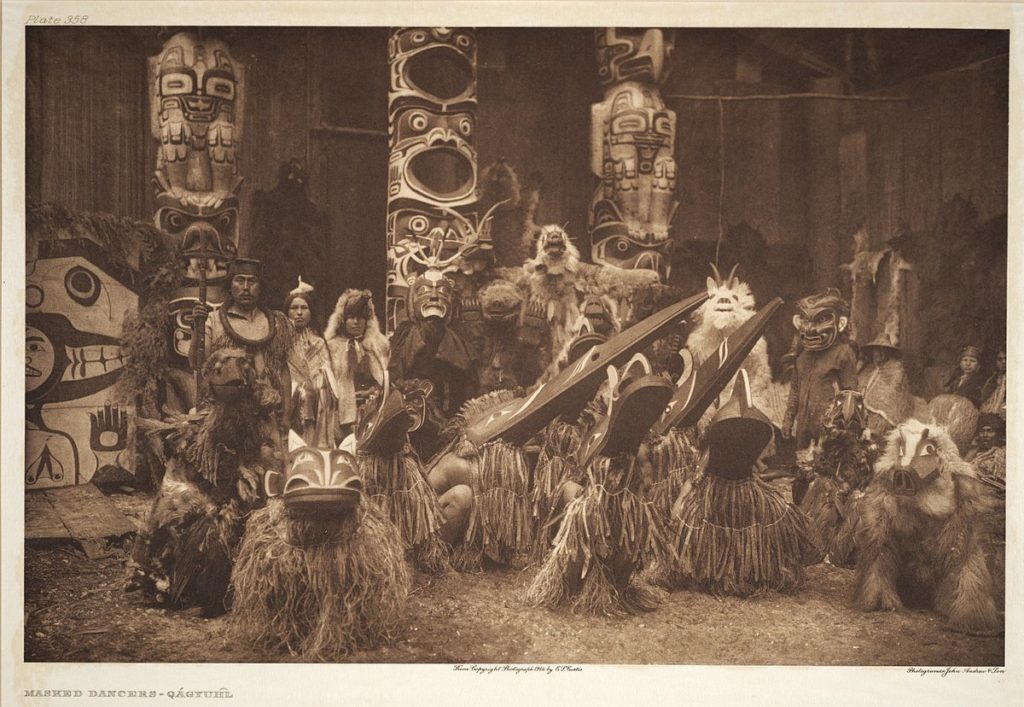

We can see Darwin’s theories apply to civilizations quite readily when examining the differences between them before the age of colonialism began the bloody march to an integrated globe. While there are structural commonalities that can be seen in all agricultural societies (like the existence of some form of division of labor), the more isolated civilizations remained from one another the more specialized and uniquely they adapted to their environment. For instance, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy maintained a fairly egalitarian social order predicated on a strict gendered division of labor between men and women.13 Their system was organized around matrilineal property relations, collective ownership of the means of production, a messianic belief in the civil-religious Law of the Great Peace, and an expansionist-genocidal relationship toward rival people’s like the Huron and Algonquians.14 Women tended to agricultural and domestic forms of labor while men hunted and made war. Each gender maintained its own rights and duties, with hereditary roles passing through families, in the confederal political structure. This division allowed the Haudenosaunee to dispose of social surplus bg engaging in aggressive territorial expansion while preserving a highly complex agricultural economy. Their temperate biome, maintained through advanced land management techniques, favored a wide-ranging agricultural society. Meanwhile, the Coast Salish organized their society around patriarchal clan structures and the Potlatch, a practice shared by other peoples like the Haida, without any sort of unified polities.15 Villages among the Coast Salish were collections of longhouses shared by allied families and the means of production (shellfishing grounds, canoes, hunting grounds, and aquacultural apparatuses) were the property of clan patriarchs.16 Even ceremonial and religious offices were held as property. The Coast Salish did not form any large spanning territorial confederations. They migrated according to seasonal changes, joining together in large communities during the rainy winter months. The natural environment, punctuated by salmon migration and seasonal mycological bounties, favored what might be called rhizomatic organization. The potlatch, a kind of ritual which established a gift economy, was the central economic mechanism binding communities together. Potlatches took the form of great feasts and contained religious and legal proceedings like marriages, namings, transfers of ceremonial office but were principally concerned with the giving of gifts by aristocrats to the leaders of other clans and the destruction of wealth as an offering to the spirits. Any gifts given to the guests were matched by at least an equal amount, or a rival chief or clan leader would face shame and a diminution of power. Commoners participated indirectly by giving gifts through a chieftain or aristocrat.17 In Coast Salish society, power was a function of how much one could give away, and thereby create obligations of debt, not how much one accumulated. This practice and social logic was so abhorrent to the settlers of the US and Canadian colonial societies that the practice was banned for many decades with harsh punishments.18 The Inca too developed an incredibly complex system with many unique features. Their society maintained a centrally-planned palatial economy which bore some parallels to what Marx called the “Asiatic mode of production.”19 The steep mountain terrace farming of the Inca required the development of highly skilled engineers and a centrally organized authority to maintain them with the social surplus. Beyond their impressive feats of engineering, one of the most fascinating aspects of Inca society was the fact they organized a continent-spanning empire without the use of an alphabet. Instead, accounting and other administrative records were recorded in quipu (devices made from knotted string).20 Being isolated from Eurasian civilizations, the Inca, and other indigenous societies, adapted to their environment in a unique and specialized manner.

The history of non-Eurasian civilizations puts a nail in the coffin of orthodox historical materialism. In The German Ideology, Marx sketches out a linear theory of development that insists all societies must go through a series of discrete “stages” punctuated sharply by revolutionary rupture.21 This viewpoint misled Communist parties across the world into serious errors like subverting the Spanish and Chinese sociaist revolutions in favor of a bourgeois-democratic “stage” and a general failure to sufficiently support socialist revolutions in the global south. Marx himself began to overcome this view later in his life, as shown in documents like his famous “Reply to Zasulich”, which argued that not all countries have to develop along the same path and that the Russian mir (peasant commune) could serve as the economic basis of a socialist society.22

Within Eurasia, the same tendency of isolation to produce specialized adaptation existed. In periods of social stability, such as during the Roman, Parthian, and Han empires, commerce and the associated free flow of ideas and technology allowed for a relative convergence between the social forms.23 This is identical to the tendency Darwin noticed in sea birds to be relatively similar morphologically across wide geographic expanses. While Rome militarily represented a conquest of the Eastern Hellenic and Semitic cultures by the west, it simultaneously represented the transformation of western Europe according to eastern civil principles and under the influence of eastern mystery religions like Christianity. Rome transformed from first a militarist-agrarian society, to a Hellenized merchanting society, to an Asiatic palatial society.24 With the collapse of Rome and the economic decentralization of Europe, localization and specialization were restored as the general tendency. But then Europe began to regain its interconnection through commerce in the wake of the Black Death’s shift of political power from the agrarian-military aristocracy into the hands of the merchants and burghurs. The Renaissance was inaugurated through the gradual accumulation of interconnections and commercial ties between European nations, the Arab states of the Levant and the outward expansion of European society in search of plunder and trade, first in Africa and then in the Americas.25 But the role of cultural interchange from ideas beyond Europe in this process cannot be understated. Without Arab science and philosophy the Renaissance is impossible. And it is Chinese philosophy that serves as the forgotten inspiration for Liberal theories of economics and civil rights. François Quesnay, the founder of the Physiocrat school (often considered the first school of economics), directly took inspiration from Confucian theories of equilibrium and natural harmony as the basis of the idea of laissez-faire economics.26 From his reading of Confucianism, Quesnay argued that it was necessary for there to exist an all-powerful enlightened autocrat who would preserve the cosmic harmony embodied in the equilibrium of the free market from the whims of the mob or selfish local aristocrats. And it is Physiocracy which would inspire Hobbes in his theory of the Leviathan, and by reaction almost the entirety of “Western” thought through adaptation of theories to new material conditions.

Rather than the specific conditions of the English countryside giving rise to capitalism, as some Marxists believe, it is the general conditions of rising global interconnection which created the conditions that allowed capitalism to emerge in the English countryside. Capitalism has only catalyzed and advanced this tendency as a side effect of its quest for profit. Neither tendency, of adaptation and specialization, or generalization and universal transmission, can fully occlude the other, and over-emphasizing one or the other can lead to either particularist chauvinism or universalist chauvinism. For comradely relations to exist, we need to respect difference while striving for greater interconnection and understanding.

In order to take the first steps toward greater understanding, we have to situate the nature of consciousness in its relation to the wider world. Consciousness is an emergent property of the cosmos. For all our responsibility, we are not separable from totality; we are merely an expression of it. On some level any sufficiently complex, self-perpetuating system demonstrates the attributes of consciousness. Consciousness is a process and a property, not a substance.27 It is the state of matter which is engaged in the overcoming of resistance. That is to say, consciousness is the organization of labor. Whether it is the labor of constructing psychic models of reality in abstract philosophy or seemingly unthinking mechanical labor, our mentality, which is wholly composed of matter in the world, is engaged in the transformation of some part of the wider world and is in turn transformed by it.

In The Philosophy of Living Experience, Alexander Bogdanov — the great Bolshevik revolutionary and progenitor of systems theory — argues that the recognition of this truth, the centrality of labor in the construction of reality and history, is vital both for the rising working class to develop the techniques necessary to successfully and permanently overthrow the international bourgeoisie, and for the construction of socialism. Bogdanov sketches out the development of the various regimes of labor, from early patriarchal communes through ancient commercial societies, feudalism and the bourgeois epoch, to the implicit socialist relations in the working-class movement. In each historical regime a different way of seeing and organizing the world predominates. In communal societies there is an authoritarian and personalist worldview which sees spirits hiding behind objects and manipulating them the same way the labor of the commune is guided by the wisdom of the elders and will of the leaders. Bogdanov also shows that in commercial societies, both ancient and modern, impersonal and abstract laws begin to govern affairs. The invisible hand of the market and “eternal” laws of Nature take hold of our imagination. This is not a linear process. The disconnected and warring fiefdoms of the feudal era represented a brief return to authoritarian communalism, but after the Black Death and severe social disruptions of the 14th through 18th century, the financial, merchant and artisan layers were able to gradually establish supremacy over the agricultural-militarist aristocracy.28

While the trajectory of history has been from authoritarian relations to abstract relations, reaching its apogee under the rule of the bourgeoisie, both kinds of relations exist simultaneously and mutually reinforce one another. While a company appeals to “market necessity” when it lays off hundreds of employees, it also claims to be a family and demands strict obedience to the traditions and rules of the leadership. The abstract necessity of bourgeois natural laws are the foundation of Modernism. Instead of a process of active co-creation, evolution is framed as an inflexible, gradual and passive necessity. For all its talk of freedom, the bourgeois worldview hems its subjects into a cold and mechanical slavery to impersonal forces. But another kind of social relationship exists: comradely cooperation. This logic is also necessary for the preservation of society, for without organic mutual aid (which is often overseen by authoritarian churches and similar organizations), public welfare, and real personal ties of support, our society would devour itself. It is this ethic and worldview which is necessary to establish a world which is sustainable, just, and fulfilling. Through solidarity, cooperation and self-sacrifice for the higher cause of freedom we will establish the cooperative commonwealth — a commonwealth that must enmesh non-human life, both synthetic and organic. If we frame our understanding of the world in a modernist way we will be overtaken by our blind and obedient machine-servants. It is the choice to make life a race that prefigures the necessary result: we will lose it. Rather than play the bourgeois rat race, we have to take a lesson from Grey Walter’s tortoises.

To develop a world where comradely cooperation can predominate, this world of antagonism and contradiction must be overcome. The ultimate antagonism created by the logic of capital accumulation, between the society of property and the mass of the propertyless it creates, between the master class and the dispossessed, must be resolved by revolution. Kenneth M. Stokes, an economist and philosopher who draws on the Soviet geologist Vladimir Vernadsky, argues that capitalism has become so naturalized that it acts as an “autonomous technosphere.” That is to say, like the biosphere which is composed of all organic life, capitalism has become a self-moving geological force that uses us as its substrate.29 It utilizes social antagonism to create islands of order and homeostasis, that perpetuate it while externalizing entropy onto the environment and marginalized populations. In simple terms, capitalism perpetuates itself by giving a small part of the world stability and wealth while shifting costs like pollution, bad work conditions, and broken public services onto others. Capitalism treats inputs as neutral; it doesn’t care if profit comes from turning a rainforest into toothpicks or if it comes from harvesting the organs of colonized children. It treats the environment as something separate from society so that it can be a resource to exploit.

Liberal environmentalism, and even much radical environmentalism, accepts this premise but just changes the value judgments about it. There is an alternative. If, through working-class revolution, humanity is able to smash the homeostasis through which the technosphere is embodied, then we can establish a new geological force: the noosphere.30 The noosphere, consciousness as a geological force, would transform the whole planet into a homeostat. Rather than treating Nature as an external object to be exploited, or an Other to subordinate oneself to, it would be treated as our inorganic body. Self-control and other classical Republican virtues will become the rule of the day and the whole planet will be our sacred Polis. In other words, communism will create the conditions for true flourishing and the free association of producers – be they organic or synthetic.