Doug Enaa Greene and Shalon van Tine discuss Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise in its historical context.

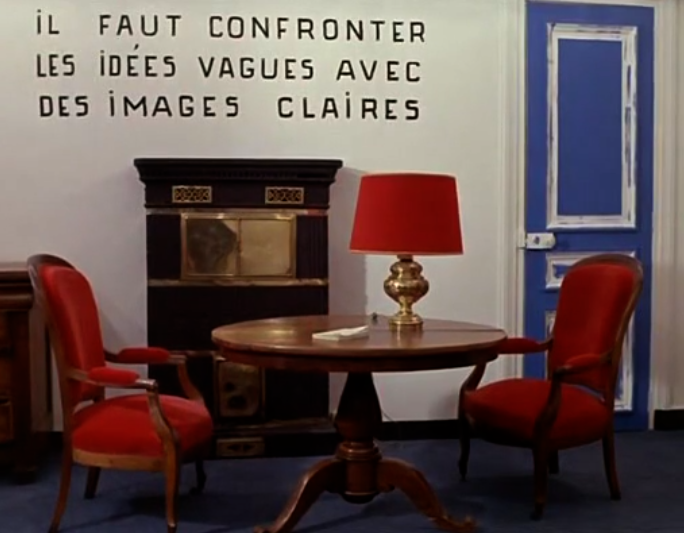

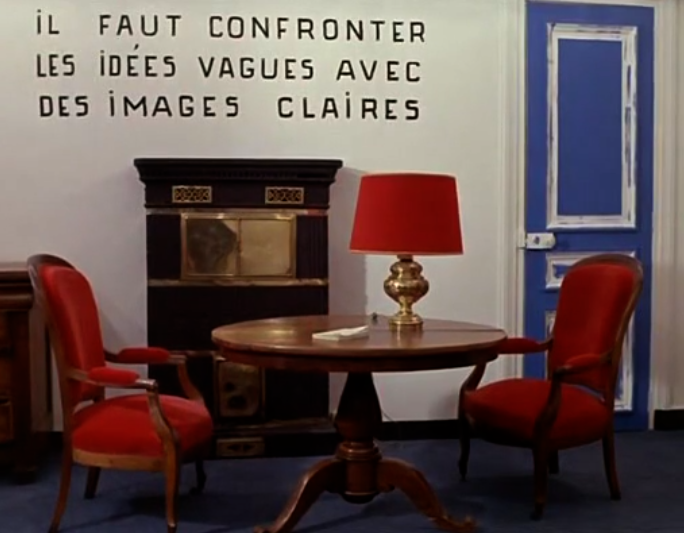

Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) is not an ordinary film. On the surface, La Chinoise seems simple enough: it tells the story of French students in the 1960s who form a Maoist collective, live together, have political discussions, and eventually turn to revolutionary violence. However, the film is difficult to follow since it not only lacks a coherent narrative structure, but the viewer is bombarded with slogans, images, and ideas on everything from popular culture to revolutionary politics. Anyone who attempts to analyze their meaning will easily feel buried by all the sights and sounds that Godard packs into it. Considering the chaotic nature of La Chinoise, the slogan found at the beginning — “We should replace vague ideas with clear images” — may well appear out of place, if not ironic.

However, this slogan encapsulates what Godard attempted to achieve in La Chinoise. Godard wanted to overcome the distortions of bourgeois ideology that prevents the viewer from seeing the world as it truly is. To achieve this aim, he wanted film to be a medium of revolution. That meant he could not rely on the way film had customarily been produced, which was usually formulaic and promoted passivity instead of rebellion. In contrast to traditional cinema, Godard wanted to create a revolutionary art form that would break with bourgeois conventions and serve as a call to arms.

He accomplished this goal by drawing upon two major sources. The first source was German playwright Bertolt Brecht and his theory of “epic theater,” a method of political theater that forces the audience to actively engage with the ideas presented to them as opposed to passively consuming them. For Brecht, the theater should be an effective tool for getting viewers to see the world as it really is, as riven by class struggle. The second source was Maoism, which gained popularity among French intellectuals during the 1960s and appeared to advance a revolutionary alternative to the stagnation found in Soviet communism. It was the impact of Maoism in the radical imagination that offered Godard an appreciation of Third World revolutionary struggles, a sophisticated theory of ideology and conjuncture mediated through the work of philosopher Louis Althusser, and the need to politicize culture in service of the revolutionary cause. While his earlier films began to toy with some of these concepts, it is in La Chinoise that Godard’s vital mix of Brechtian aesthetics and Maoist ideas is most fully realized.

Becoming Godard

Godard’s personal development contributed to his interaction with film later in his life. He grew up in a cultured home where reading literature aloud was a normal form of entertainment. As a child, he rarely went to the movies. Rather, he preferred to read philosophy, cultural theory, and the classics. His first attachment to cinema came from French intellectual André Malraux’s essay “Sketch for a Psychology of the Moving Pictures,” which made connections for him between film, literature, and theater. When Godard attended university, he studied under Brice Parain, a French philosopher whose work revolved around linguistics, communism, and existentialism. Later, Godard moved into the world of cinema, first as critic, and then as director. Godard would eventually quote Malraux and Parain’s ideas about the linguistic and political possibilities of film in one of his earliest essays “Towards a Political Cinema.” It comes as no surprise, then, that Godard’s philosophical and literary training prepared him for a whole new approach to film.

Along with his contemporaries, Godard was one of the key innovators of the French New Wave, a film movement that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. New Wave directors strayed from traditional film form by experimenting with editing and narrative techniques, giving homage to classic cinema, and using film for social commentary, especially as it applied to the younger generation. Many of the New Wave directors were intellectually tied to Cahiers du Cinéma, one of the first journals to analyze film as a serious art form. These filmmakers would later channel their theories and appreciation of cinema into their own movies.

In 1960, Godard released his first film, Breathless (À bout de souffle). Breathless is most remembered for its use of jump cuts, an editing technique where two shots are filmed from slightly different positions, giving the viewer a fragmented sense of time. Long before figures like filmmaker Quentin Tarantino referenced pop culture in his movies, Godard initiated this practice, paying tribute to Hollywood and classical music in all his early films. Godard also relied upon character asides, where characters break the fourth wall and speak directly to the audience. This theater technique forces the viewer to participate in the action within the film rather than passively observe it.

Godard continued to challenge cinematic conventions with his early films, eventually incorporating more experimental techniques into his movies that gave him his signature style. As he became more politically involved, he looked to cultural theorists for aesthetic inspiration and attempted to renovate the language of cinema altogether.

The Language of Cinema

As film director François Truffaut said, “There is cinema before Godard and cinema after Godard.” Before Godard, cinema had a traditional language and narrative structure that moviegoers had come to expect. Godard revolutionized filmmaking by upending the traditional storytelling techniques and cinematic language in the hopes of transforming film into a revolutionary art form.

By the 1960s, Godard believed that the majority of films were formulaic products that promoted consumerism and complacency, not revolutionary consciousness. In making this assessment, he was influenced by the ideas of Frankfurt School theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s analyses of the culture industry. Adorno and Horkheimer argued:

Culture today is infecting everything with sameness. Film, radio, and magazines form a system. Each branch of culture is unanimous within itself and all are unanimous together. Even the aesthetic manifestations of political opposites proclaim the same inflexible rhythm… All mass culture under monopoly is identical… Films and radio no longer need to present themselves as art. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce.

Often misunderstood as elitist or pessimistic, Adorno and Horkheimer criticized the ways that the culture industry mass-produced entertainment products for the sole purpose of profit. Mainly, they aspired to understand why the oppressiveness of capitalism did not spur revolution as Marxists before them had hoped. As they argued, the culture industry purposely suppresses people’s inclination to revolt by ensuring they have plenty of consumable products that are both easily pleasurable and familiar. After all, the culture industry is a business—a profit-motivated behemoth—so all products are designed with the intent to maintain the status quo, not stimulate revolutionary thinking.

Regarding Hollywood directors, Adorno and Horkheimer quipped, “Published figures for their directors’ incomes quell any doubts about the social necessity of their finished products.” Agreeing with this analysis, Godard accused the film industry of being “capitalism in its purest form,” and he argued that there was “only one solution, and that is to turn one’s back on American cinema.” Godard wished to counter this psychological hold by the film industry (or as he called it, “The Hollywood Machine”) with a new cinema that was innovative, challenging, and hopefully, revolutionary. To do so, he needed to change the very language of cinema itself.

Godard eventually began referring to his movies as “essays,” saying, “I don’t really like telling a story. I prefer a kind of tapestry, a background on which I can embroider my own ideas.” Engaging with the semioticians Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, Godard saw film as a sign system, or as film critic James Hoberman claimed, Godard was “the first filmmaker to perceive film history as a text.” This approach is evidenced in the ways that he spliced images with intertitles and dialogue as if he was making a philosophical argument rather than telling a story. However, Godard took issue with some of the prevailing structuralist views on cinema, considering them too rigidly focused on universal symbolism. In one heated debate about semiotics within film, Godard yelled at Barthes, declaiming “We are the children of the language of cinema. Our parents are Griffith, Hawks, Dreyer, Bazin, and Langlois, but not you!”, and questioning whether one can “address structures without sounds and images”.

In contrast to the films produced by the culture industry, Godard resisted the traditional film language by creating mostly plotless films with emotionless characters, often breaking the fourth wall to conduct a political rant or in dialogue that would be interrupted by the intrusion of unrelated images or voice-over commentaries. As film professor Louis Giannetti describes, these tactics remind the viewer that the film is “ideologically weighted” and that the audience “should think rather than feel, analyze the events objectively rather than enter them vicariously.” These methods allowed Godard to consider his films as treatises—not just as artistic creations, but as mediums for conveying a grab-bag of aesthetic and theoretical ideas. As English film theorist Peter Wollen explains:

There is no pure cinema, grounded in a single essence, hermetically sealed from contamination. This explains the value of a director like Jean-Luc Godard, who is unafraid to mix Hollywood with Kant and Hegel, Eisensteinian montage with Rossellinian realism, words with images, professional actors with historical people, Lumière with Méliès, the documentary with the iconographic. More than anybody else, Godard has realized the fantastic possibilities of the cinema as a medium of communication and expression. In his hands, as in Peirce’s perfect sign, the cinema has become an almost equal amalgam of the symbolic, the iconic, and the indexical.

For Godard, the language of cinema could be used as a powerful tool to get across ideological concepts that were more difficult to convey in an established, linear format. The epitome of this shift is seen in La Chinoise, which makes the case against the conventions of bourgeois culture and in favor of a revolutionary culture though dramatic visual fashion.

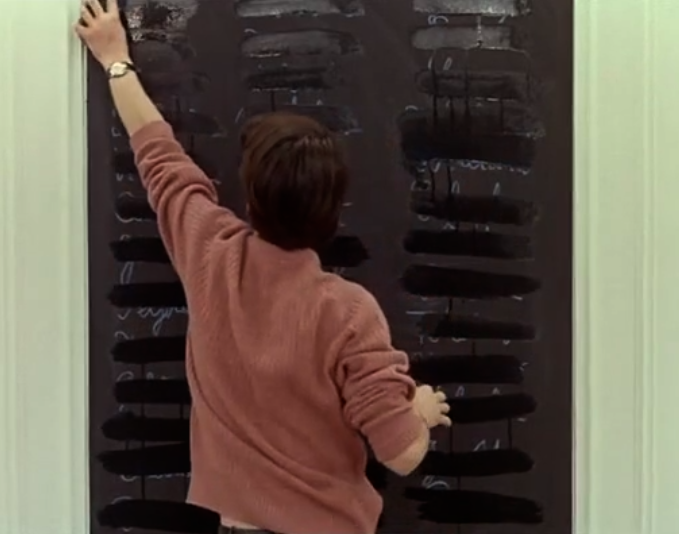

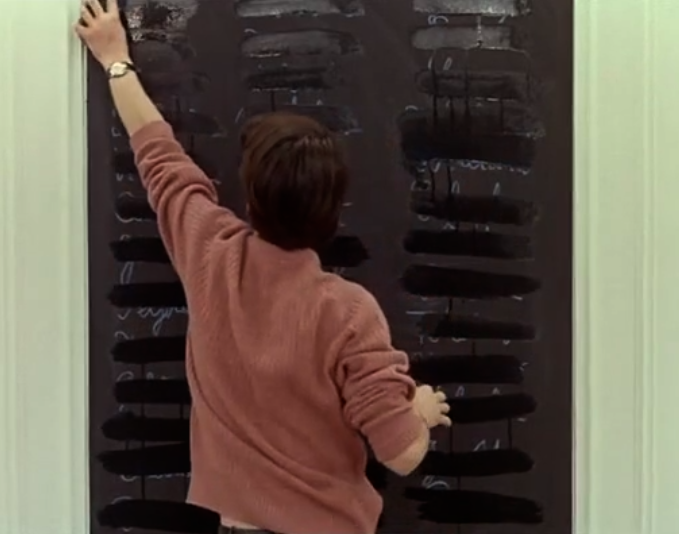

For instance, in the film’s second act, Guillaume, one of the militants, stands in front of a chalkboard. On the board are scribbled a couple dozen names of philosophers, writers, filmmakers, and artists. In the background, Kirilov, another militant, lectures on the purpose of art for the communist cause while Guillaume erases each their names one by one: Voltaire, Cocteau, Goethe—each eliminated leaving only one name: Brecht. Kirilov argues that the last century of artistic production has shifted from the creation of art-for-art’s-sake to “art as its own science.” Using poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein as examples of those “fighting for a definition of socialist art,” Kirilov asserts that art is no longer merely an attempt to represent reality, but is rather a social and political force that creates or reveals reality, or, as he puts it, “art doesn’t reproduce the visible—it makes visible.”

A key premise in Kirilov’s argument is that art is language that effects change or uncovers hidden truths. Those who resist this notion do so under the false pretense that the language of art is incomprehensible. Yet he points out that it is actually society itself that is “hermitic and closed up,” and that traditional political discourse is “the poorest of languages as possible.” Drawing upon the ideas presented in The Order of Things, Godard uses Kirilov’s lesson to expound on philosopher Michel Foucault’s concept of the episteme, the body of thought that shapes the knowledge of an era. For Foucault, standard language is wrapped up in the classical episteme, where ideas are subject to taxonomical representations. But the modern episteme embodies new linguistic conventions that transcend older paradigms.

Take the end of Kirilov’s lecture, for instance. He notes how the formalists demand specific techniques that adhere to long-held artistic rules: “Use only three colors. The three primary colors: blue, yellow, and red. Perfectly pure and perfectly balanced.” Godard uses these primary colors heavily in the film, but they are displayed in an ironically unbalanced way as if to blatantly ridicule traditional aesthetic form. Kirilov continues, saying that the aesthetic image is untrustworthy, that one must consider “the position of the seeing eye, the object seen, and the source of light” when evaluating a visual idea. Godard, through Kirilov, is applying semiotic language to artistic analysis. Godard focuses not just on the artwork itself, but he also places equal importance on perception. In other words, aesthetic analysis cannot be limited to the art object itself, but must include the perspective of the viewer. And in true Maoist fashion, Kirilov concludes his lecture by paraphrasing the Great Helmsman: “In literature and in art, we must fight on two fronts.”

The types of arguments made throughout La Chinoise could not be conveyed as effectively through a standard style of filming, which was committed to upholding the dominant ideology. Instead, Godard manipulated the language of cinema to challenge the prerogatives of bourgeois ideology and promote socialist politics.

Brecht and Socialist Theater

Politics have always played a role in the theater, but political theater took new form in the twentieth century. Rather than simply remaining an outlet for social commentary, theater became a medium for political action. Communist revolution spurred agitprop within the arts, but this style often made characters flat and unrealistic. Brecht instead created a sophisticated political theater (which he deemed “dialectical theater”) that conveyed Marxist ideas and forced the audience to face the realities presented to them. As he noted:

Socialist Realism means realistically reproducing the way people live together by artistic means from a socialist point of view. It is reproduced in such a way as to promote insight into society’s mechanisms and motivate socialist actions. In the case of Socialist Realism, a large part of the pleasure that all art must inspire is pleasure at the possibility of society’s mastering human fate. A Socialist Realist work of art lays bare the dialectical laws of movement of the social mechanism, whose revelation makes the mastering of human fate easier. It provokes pleasure in their recognition and observation. A Socialist Realist work of art shows characters and events as historical and alterable, and as contradictory. This entails a great change; a serious effort has to be made to find new means of representation. A Socialist Realist work of art is based on a working-class viewpoint and appeals to all people of goodwill. It shows them the aims and outlook of the working class, which is trying to raise human productivity to a tremendous extent by transforming society and abolishing exploitation.

Brecht felt that the classical view of theater as catharsis left the audience complacent and indolent. He wanted the audience to think critically about exploitation, oppression, and class struggle. As opposed to the dramatic techniques of the past, epic theater reminded the viewer that the play is merely a representation of reality rather than reality itself, and thus the reality presented could be changed, making theater a catalyst for revolutionary action.

Godard was strongly influenced by Brecht’s theories and used them in his films, particularly his concept of verfremdungseffekt, or the alienation effect. Brecht described the alienation effect as performing “in such a way that the audience was hindered from simply identifying itself with the characters in the play,” and that the viewer’s “acceptance or rejection of their actions and utterances was meant to take place on a conscious plane, instead of, as hitherto, in the audience’s subconscious.”

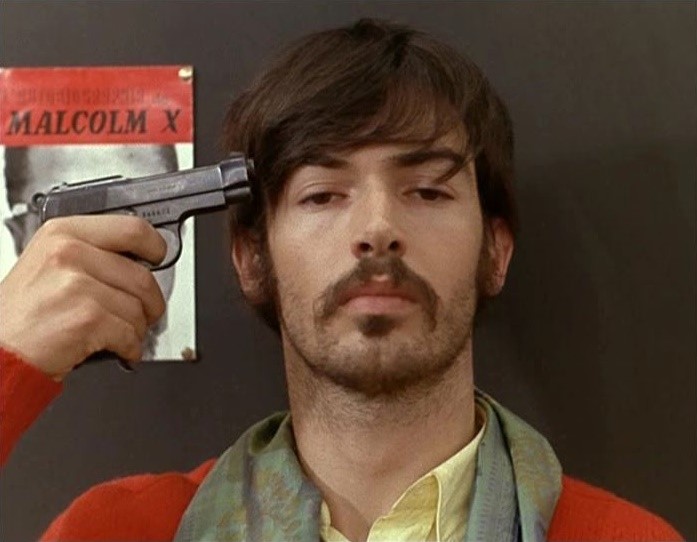

Godard employs the alienation effect frequently in La Chinoise by making his characters speak directly to the audience and juxtaposing seemingly unrelated imagery side-by-side. Take the scene in which Guillaume, after arguing that revolutionaries need “sincerity and violence,” looks directly at the camera and says, “You’re getting a kick out of this. Like I’m joking for the film because of all the technicians here. But that’s not it. It’s not because of a camera. I’m sincere.” Guillaume continues to address the viewer by explaining what “socialist theater” is by telling a story about Chinese students protesting in Moscow. In this story, one student approached the Western reporters with his face covered in bandages, yelling, “Look what they did to me! Look what the dirty revisionists did!” When the students removed the bandage, the reporters eagerly awaited a cut-up face of which to take sensationalist photos. But when the bandages were removed and the student’s face was fine, the reporters became angry saying, “This Chinaman’s a fake! He’s a clown! What is this?!” But the reporters did not realize the significance of the demonstration. Guillaume explains: “They hadn’t understood. They didn’t realize it was theater. Real theater. Reflection on reality. Like Brecht or Shakespeare.”

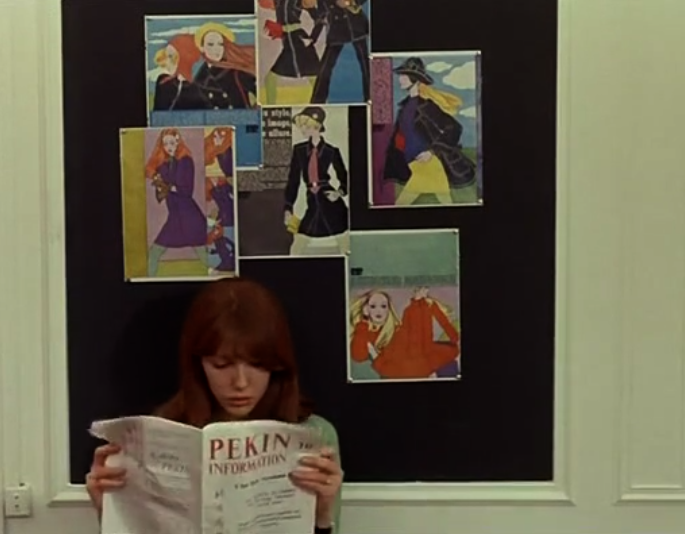

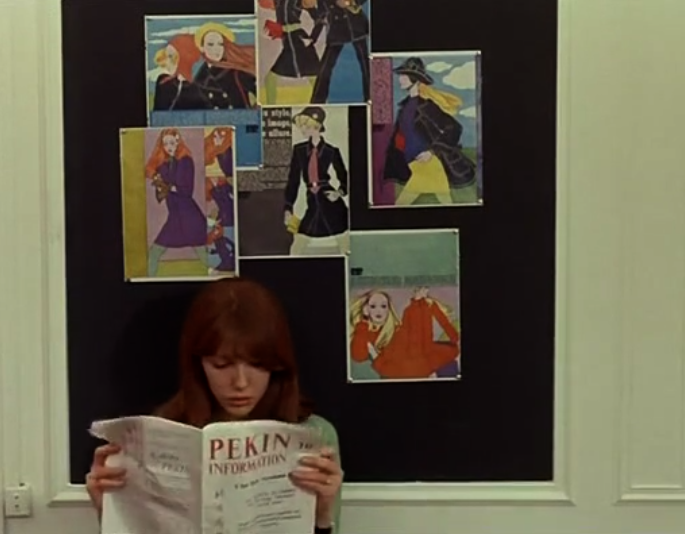

Godard also applied Brecht’s theories on theater by either confronting the audience directly or interrupting the natural narrative flow. In one instance, Godard turns the camera directly on the viewer, creating an uneasy sense of self-reflexivity as if it is the viewer who is being filmed and questioned. As writer Susan Sontag claimed, this tactic was Godard’s way of “effectively bridging the difference between first-person and third-person narration.” Additionally, most scenes in La Chinoise layer seemingly unrelated images on top of one another, forcing the audience to critically examine their meaning. For example, one scene shows a decrepit Christ statue against the recurring motif of a shelf displaying Mao’s Little Red Books while a disembodied voice pleas, “God, why have you forsaken me?” only to be answered by another faceless voice: “Because I don’t exist.” In another instance, Guillaume lectures on the importance of “seeing the inherent contradictions” in analyses of the revolutionary situation, while the camera focuses on Véronique, copy of Peking Information in hand, against a background of fashion magazine advertisements. This tactic of juxtaposing rebellious youth against culture industry images was used frequently by Godard as a way to demonstrate the contradictory nature of student activists during the 1960s — or as he called them, “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola.”

Another technique Brecht used was interrupting his plays with seemingly unconnected songs or stage directions. Godard took up this approach as well, often placing intertitles or music unexpectedly in the middle of scenes. Consider the scene where Véronique intensely studies Maoist theory as the radio plays a satirical pop song with the lyrics “Johnson giggles and me I wiggle Mao Mao,” or the way that Godard inserts a Baroque concerto in between discussions about revolutionizing old art forms. Brecht and Godard both understood the power of contrast in political imagery, and they compelled their audiences to find connections amidst the contradictions.

Consider too the various scenes within the film where Véronique and Yvonne act out skits about American imperialism or the Vietnam War. These miniature plays-within-a-play at once parody both the contemporary events being acted out and the actions of the characters themselves. These scenes were also Godard’s way of employing the Brechtian technique of spass, literally translated as “fun.” By including comedic bits in between serious political rhetoric, making sense of the commentary is left up to the audience. In other words, Godard makes the audience work for their understanding of the ideas rather than passively absorbing them.

Godard’s attempt to make La Chinoise his version of socialist theater is most realized in the larger story itself. The film is loosely based on Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Demons, which follows five disgruntled radicals who plot to overthrow the Russian regime through insurrectionary violence. The radicals hold meetings to flesh out their various ideological positions, yet these gatherings often turn into pissing contests or merely the recitation of empty platitudes. Dostoevsky suggests that the radicals are idealistic and hubristic, and that revolution will inevitably fail.

It is curious, then, that Godard would choose this story as the basis for La Chinoise. Dostoevsky’s critiques stemmed from a conservative position, yet Godard was a staunch Marxist (from 1968 onward) and a strong supporter of revolutionary student movements. Throughout the film, the characters are portrayed as being serious in their objectives but also childish in their approach. One could deduce that Godard intended this foundational storyline as a warning: revolution is indeed necessary, but it requires discipline and maturity.

Godard’s innovations in cinema reflected his desire to make the screen a vehicle for socialist politics. As his personal politics continued to move leftward, his filmmaking became increasingly political as well. For Godard, the cinema was more than just an art form—it was becoming for him a mode for revolutionary action.

Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win

a. Power to the Imagination

It was not just Brecht who informed Godard’s ideas, but those of Mao. Like the characters in La Chinoise, Godard was caught up in a Maoist revolutionary fever that was shared by many French intellectuals and students during the 1960s. Godard’s Maoist commitment went beyond cinema. Three years after the film was released, Godard was involved in the French Maoist movement. When the Maoist publication La Cause du Peuple was banned by the French government and its editors in the spring of 1970, Godard helped to collate the paper while the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre took over as editor. Godard was willing to risk arrest in service of the revolutionary cause.

According to Maoist philosopher Alain Badiou, this period was a “red decade” that

stemmed from the intellectual effect of the Sino–Soviet ideological conflict and the Cultural Revolution, and was followed decisively by the events of May 1968 and their aftermath. Its watchwords were those of Maoism: direct joining of forces by intellectuals and mass workers; ‘it is correct to revolt’; ‘down with the bourgeois university’; ‘down with the PCF revisionists’; creations of autonomous organisations in the factories against the official unions; defensive revolutionary violence in the streets against the police; elections, betrayal; and so on. Everyday life was entirely politicised; daily activism was the done thing.

Indeed, revolution truly seemed to be in the air.

However, in an ironic twist, this new French adherence to Maoism and the Chinese Revolution was coupled with a profound ignorance of its practice in the East. When it came to the reality of Maoism in China, most French radicals preferred viewing the experience through rose-colored glasses. As historian Richard Wolin observed, for French radicals, “Cultural Revolutionary China became a projection screen, a Rorschach test, for their innermost radical political hopes and fantasies, which in de Gaulle’s France had been deprived of a real-world outlet. China became the embodiment of a ‘radiant utopian future.’”

In other words, for many French leftists, the importance of Maoism was its myth. For example, the Maoist activist Emmanuel Terray recognizes that his comrades embraced a myth, but does not disavow his political past:

I was like many others a fervent partisan—from France—of the Cultural Revolution. But I don’t consider this to be a regrettable youthful error about which it would be better to be silent today, or, on the other hand, to make an ostentatious confession. I know today, of course, that the Cultural Revolution we dreamt about and that inspired part of our political practice didn’t have much in common with the Cultural Revolution as it was lived out in China. And yet I am not ready to put my former admiration into the category of a mental aberration. In fact, the symbolic power of Maoist China operated in Europe at the end of the sixties independently of Chinese reality as such. “Our” Cultural Revolution was very far from that, but it had the weight and the consistency of those collective representations that sociology and anthropology have studied for so long.

Similar to Terray and other French Maoists, Godard’s Maoism was not so much about the reality on the ground in China, but rather acted as a mobilizing myth to inspire and formulate a new revolutionary, democratic, and egalitarian politics.

b. The Stormcenters of Revolution

By the mid-1960s, it is no accident that Godard looked to Mao Zedong, the Chinese Revolution, and the Third World as a source of inspiration. For a generation of young revolutionaries, like the Maoists portrayed in La Chinoise, the Algerian War was a watershed event that proved both the French Communist Party and the USSR were insufficiently anti-imperialist.

From 1954 to 1962, France fought a brutal war against the National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria, which was characterized by guerrilla warfare, terrorism, and the widespread use of torture by the French Army. The war brought down the Fourth Republic, led to the return of Charles de Gaulle to power, and brought France to the brink of civil war. According to Marie-Noelle Thibault:

The Algerian War opened the eyes of a whole generation and was largely responsible for molding it. The deep horror felt at the atrocities of the colonial war led us to a simple fact: democracies are imperialist countries too. The most important feature [was that] political action, including support for national liberation struggles, was conceived of as a mass movement.

No doubt the Algerian War shaped the anti-imperialist worldview of future Maoist cadre.

The Maoists would have been familiar with the behavior of the French Communist Party (PCF) during the war. When the war began, the PCF offered only tepid solidarity to Algeria, preferring a negotiated settlement and condemning the actions of the FLN as terrorism. Two years later, the PCF voted in favor of granting emergency powers to the government, which allowed France to send troops to Algeria. Eventually, the PCF came around to supporting Algerian independence, but their support was lukewarm and half-hearted at best. The PCF position on Algeria gave the Maoists in La Chinoise plenty of ammunition for denouncing the party as revisionist.

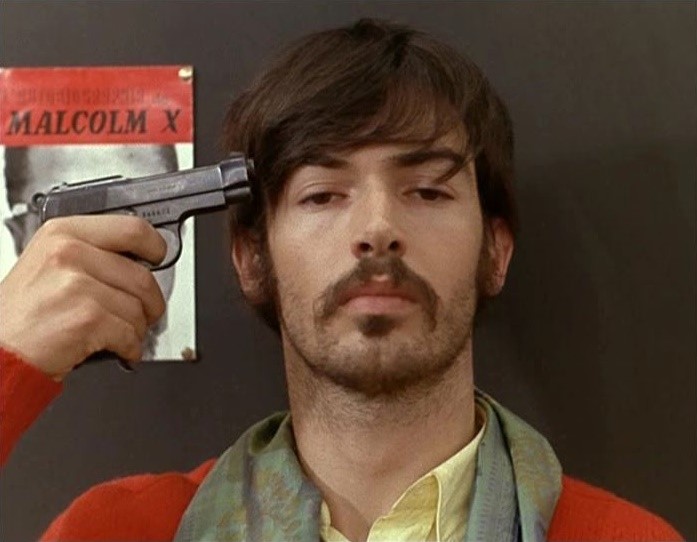

This gulf between the PCF and the French Maoists is vividly on display in La Chinoise. When Henri defends the PCF line of a peaceful transition to socialism and defense of the USSR, he is denounced and heckled by his comrades as a counterrevolutionary and a revisionist. Eventually, Henri is driven from their cell. To the Maoists, there could be no peaceful coexistence under the same roof between revolutionaries and revisionists. They remembered how the PCF and USSR failed to support the struggle in Algeria and to intervene in the then- ongoing Vietnam conflict.

The PCF’s caution on Algeria opened up space for a new generation of leftists or “gauchists” to lead opposition to the war. These gauchists ranged from future Maoists, Trotskyists, and independent leftists such as Sartre and Francis Jeanson (who played himself in La Chinoise, debating political violence with Véronique, acted by real-life student Anne Wiazemsky). These gauchists encouraged draft resistance in the French army, passed out leaflets in support of the FLN, and conducted mass demonstrations that were met with violence. Some, such as Jeanson and the Trotskyists, went further by smuggling arms and funds to the FLN. To the PCF, the leftists’ actions were beyond the pale, and the party

rejected the “harmful” attitudes of gauchiste [leftist] elements who had preached insubordination, desertion, and rejection of the very fundamentals of the national community and the national interest of the working class in peace. Their irresponsible actions, the party argued in 1962 and in 1968, had only served to assist the policies and the provocations of the Gaullist regime and the ultras.

During the Cultural Revolution, when Mao asked where the capitalist roaders were located, he answered: in the Communist Party. Many French Maoists saw this warning confirmed in the PCF’s behavior, as they played an increasingly bourgeois role (whether during the Algerian War, or in 1968, when the party stood with the French state against a student-worker general strike).

Unlike the PCF, who saw themselves as French communists and defenders of the republican tradition, the reality of the Algerian War spotlighted for the far left the hypocrisy between France’s official humanist and universalist proclamations of liberté, égalité, fraternité, and the reality of colonialism. As Sartre eloquently put it in his preface to Frantz Fanon’s Wretch of the Earth:

First, we must face that unexpected revelation, the strip-tease of our humanism. There you can see it, quite naked, and it’s not a pretty sight. It was nothing but an ideology of lies, a perfect justification for pillage; its honeyed words, its affectation of sensibility were only alibis for our aggressions. A fine sight they are too, the believers in non-violence, saying that they are neither executioners nor victims. Very well then; if you’re not victims when the government which you’ve voted for, when the army in which your younger brothers are serving without hesitation or remorse have undertaken race murder, you are, without a shadow of doubt, executioners. And if you chose to be victims and to risk being put in prison for a day or two, you are simply choosing to pull your irons out of the fire. But you will not be able to pull them out; they’ll have to stay there till the end. Try to understand this at any rate: if violence began this very evening and if exploitation and oppression had never existed on the earth, perhaps the slogans of non-violence might end the quarrel. But if the whole regime, even your non-violent ideas, are conditioned by a thousand-year-old oppression, your passivity serves only to place you in the ranks of the oppressors.

Once the Algerian war ended, this experience shaped a new generation of leftists (including future Maoists) in understanding the connection between anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism. By the mid-1960s, the Third World appeared to many leftists to be a “storm center of revolution” with anti-imperialist movements, often led by Marxists, leading struggles in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. To the Maoists in La Chinoise, the following expression of Mao would have seemed a simple statement of fact:

There are two winds in the world today, the East Wind and the West Wind. There is a Chinese saying: “Either the East Wind prevails over the West Wind or the West Wind prevails over the East Wind.” I believe it is characteristic of the situation today that the East Wind is prevailing over the West Wind. That is to say, the forces of socialism have become overwhelmingly superior to the forces of imperialism.

Vietnam was like Algeria—a small David defying the American imperialist Goliath. The victory of the Vietnamese could only enhance the prospects for world revolution, so their struggle, like that of Algeria, must be supported. In La Chinoise, the Maoists recognized the progressive character of the Vietnamese struggle by repeating a quotation from Mao: “All wars that are progressive are just, and all wars that impede progress are unjust. We communists oppose all unjust wars that impede progress, but we do not oppose progressive, just wars.”

In the film, the characters note the different response of the Soviet Union and China to the Vietnam War. In this disparity, the Maoists believe they see what separates the real communists from the revisionists. As Guillaume notes in a lecture devoted to the Vietnam War, the Soviet Union is not supporting the Vietnamese, but is more interested in making deals with the United States. He believes this proves that

there are two types of communisms. A dangerous one, and one not dangerous. A communism Johnson must fight, and one he holds out his hands to. And why is one of them no longer dangerous? Because it has changed. The Americans haven’t. They’re an imperialist power. Since they haven’t changed, then it’s the others who’ve changed. The Russians and their friends have become revisionists that the Americans can get on with, while the real communists that haven’t changed need to be kicked in the face. That’s what Vietnam’s about. Whether intentionally or not, both the Russians and Americans are fighting the real communists, in China. That’s the general conclusion.

While Vietnam, like Cuba, was a source of inspiration and action for sixties leftists, they remained firmly allied to Moscow. By contrast, China and Maoism openly challenged the Soviet Union for leadership over the international communist movement by presenting a revolutionary alternative. In contrast to the Soviet line of upholding the international status quo, the Chinese preached that there could be no “peaceful coexistence with imperialism” (though in actuality, Chinese foreign policy was more characterized by cynical realpolitik):

It is one thing to practice peaceful coexistence between countries with different social systems. It is absolutely impermissible and impossible for countries practicing peaceful coexistence to touch even a hair of each other’s social system. The class struggle, the struggle for national liberation and the transition from capitalism to socialism in various countries are quite another. thing. They are all bitter, life-and-death revolutionary struggles which aim at changing the social system. Peaceful coexistence cannot replace the revolutionary struggles of the people. The transition from capitalism to socialism in any country can only be brought about through the proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat in that country.

The appeal of Maoism was not only that Mao was anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist, but because the Chinese Revolution appeared to offer a living example of renewing communism compared to the exhausted Soviet model. Maoism also offered a coherent worldview that linked anti-imperialism with anti-capitalism, showing that all are involved in the same struggle against imperialism, whether in France, Algeria, or Vietnam.

The Maoist call for revolutionary struggle against imperialism—as opposed to cutting deals—found receptive ears among communists throughout the world, including the students in La Chinoise. In fact, the response of French leftists to the Vietnam War appeared to follow the same pattern as during the Algerian War. The PCF anti-war group Mouvement de la Paix presented uninspiring slogans of “Peace in Vietnam,” while conducting no militant work in the factories, the schools, or the streets. It seemed more concerned with maintaining its respectable image and winning votes than effectively opposing the Vietnam War. By contrast, the Maoist UJC (M-L), who organized around Comite Vietnam de base, openly called for “FNL Vaincra” (“Victory for the Vietnamese Liberation Front”). More than their respective slogans, the Maoist anti-war movement conducted a very different politics than the PCF by undertaking direct action and organizing not only on the campuses, but in the streets, outside the factories, and in immigrant neighborhoods.

In the film, there is a sharp contrast between the Soviet and Maoist positions on Vietnam. While Guillaume delivers his lecture, Yvonne is dressed as a bloodied Vietnamese peasant who is being attacked by toy American planes. She cries out in despair for help to the USSR: “Help, help, Mr. Kosygin!” (Aleksej Kosygin was then one of the leaders of the Soviet Union). No help comes. By contrast, the Maoist position is dramatically symbolized by throwing dozens of Red Books to knock over a toy American tank.

c. The Althusser Encounter

It was not just Third World Revolution and China’s challenge to Soviet hegemony among communists that Godard portrayed in La Chinoise. He was also interested in the revolutionary and intellectual fervent that was beginning to be felt among French students in the shape of Maoism. La Chinoise foretold the student radicalism and Maoism that was brewing before the explosion of May 1968, only a year after the film’s release.

In 1966, Anne Wiazemsky (the actress who played Véronique and Godard’s romantic interest at the time) was a student at Nanterre, which was located in a working-class neighborhood that was a hotbed of leftist activism. Godard met Véronique’s leftist friends and professors (including Francis Jeanson, who subsequently appeared as himself in La Chinoise), but he wanted to meet the most dynamic of them, who were cloistered around the Maoist journal Cahiers Marxistes-Léninistes (featured prominently in the film), located at the prestigious École normale supérieure (ENS).

A contact was arranged with Godard by Yvonne Baby (her father was a leading Communist Party member expelled for Maoism), a film critic at Le Monde. One of Baby’s colleagues was Jean-Pierre Gorin, a literary critic who happened to have gone to school with the student Maoists. Upon meeting Gorin, Godard informed him that he wished to make a film on the French Maoists. Gorin seemed interested enough, and he began meeting regularly with Godard. Later, Gorin introduced Godard to the Maoists at ENS. Among their leaders was Robert Linhart, who had been expelled from the communist student group and was a former student of Louis Althusser.

Louis Althusser was a Communist Party member, a quiet critic of the party line, and a professor at ENS. He published For Marx and Reading Capital in 1965, propelling him into intellectual stardom. While Althusser was a leading communist theorist, he was also a subdued critic of the party’s reformist line and a Maoist sympathizer. Godard himself took Althusser’s ideas seriously since they informed the worldview of the Maoist militants at the center of La Chinoise. As a result, La Chinoise’s Maoism possesses a distinctive Althusserian tinge, placing emphasis on the necessity of ideological and theoretical struggle.

Partway through the film, the young Maoists gather for a forum on the “Prospects for the European left.” Presiding over the event is a guest speaker named Omar Diop, the only authentic Maoist revolutionary to appear in La Chinoise. Diop would later work closely with May ‘68 student leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit, and eventually was arrested and probably murdered by the Senegalese authorities in May 1973.

In the scene, Omar stands by the lectern and addresses the Maoists. He says that that the death of Stalin

has given us the right to make a precise accounting of what we possess, to call by their correct names both our riches and our predicament, to think and argue out loud about our problems, and to engage in the rigors of real research. This moment has allowed us to emerge from our theoretical provincialism, to recognize and engage with the existence of others outside ourselves. And on connecting with this outer world, to begin to see ourselves better. It has allowed us to develop an honest self-appraisal by laying bare where we stand in regard to the knowledge and ignorance of Marxism. Any questions?

Omar’s speech is, in fact, a close paraphrase from Althusser’s introduction to For Marx. The death of Stalin and his subsequent denunciation by Nikita Khrushchev in 1956 had caused a crisis in the international communist movement. Althusser argued that Stalin had “snuffed out not only thousands upon thousands of lives, but also, for a long time, if not forever, the theoretical existence of a whole series of major problems,” eliminating “from the field of Marxist research and discovery questions that fell by rights to the province of Marxism.”

According to Althusser, bourgeois ideologies like humanism filled the theoretical void that remained after the death of Stalin. By adopting humanism, Althusser argued that communists were

following the Social-Democrats and even religious thinkers (who used to have an almost guaranteed monopoly in these things) in the practice of exploiting the works of Marx’s youth in order to draw out of them an ideology of Man, Liberty, Alienation, Transcendence, etc.—without asking whether the system of these notions was idealist or materialist, whether this ideology was petty-bourgeois or proletarian.

The political effect of theoretical humanism among Marxists was the promotion of the peaceful transition to socialism, which justified class collaboration and a rapprochement with social democracy. This theoretical humanism was something eagerly embraced by the PCF since it provided a justification for their reformist politics (and ferociously rejected by the Maoists in La Chinoise).

Contrary to the PCF, Althusser argued that Marxists who were beholden to humanism were incapable of providing a viable scientific basis for Marxism. Althusser believed that it was the mission of Marxists such as himself to provide that theoretical and scientific foundation. One source that Althusser utilized in that task was Mao’s writings on dialectics, especially the distinction between primary and secondary contradictions, found in his 1937 work, On Contradiction. Here, Mao argued that every situation is characterized by many contradictions, but that at any time, “there is only one principal contradiction which plays the leading role.” Under capitalism, the principal contradiction in capitalism is between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, and other contradictions, such as between imperialism and colonized peoples, were secondary. Furthermore, the proletariat was the principal aspect of the contradiction, which would eventually triumph over the bourgeoisie. However, since reality is dynamic, contradictions develop unevenly and dynamically, and thus contradictions and their aspects often shifted, rather than being pinned in place. In connection with this Mao emphasized that

at every stage in the development of a process, there is only one principal contradiction which plays the leading role… Therefore, in studying any complex process in which there are two or more contradictions, we must devote every effort to funding its principal contradiction. Once this principal contradiction is grasped, all problems can be readily solved.

The concrete lesson that Althusser drew from Maoist dialectics was the need for a conjunctural analysis, defined as the present moment that is made up of a combination of the social contradictions and the balance of class forces. According to Althusser, an investigation of a conjuncture needs to take into “account of all the determinations, all the existing concrete circumstances, making an inventory, a detailed breakdown and comparison of them.” A conjunctural analysis is an inventory of the relations between classes, social contradictions, and the role of the state. However, a conjunctural analysis not a neutral research project, but according to Louis Althusser, it “poses the political problem and indicates its historical solution, ipso facto rendering it a political objective, a practical task.” Mao and Althusser’s theory of contradictions and their mobile nature meant careful investigation was needed to determine when to act and what appropriate strategies were to be pursued. As Véronique, Henri, Guillaume explain to Yvonne:

Because an analysis of a specific situation, as Lenin says, is the essential… the soul of Marxism… It’s seeing the inherent contradictions… Because things are complicated by determining factors. Yes, Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin teach us to carefully study the situation very conscientiously. Starting from objective reality, not from our subjective desires… We must examine the different aspects, not just one.

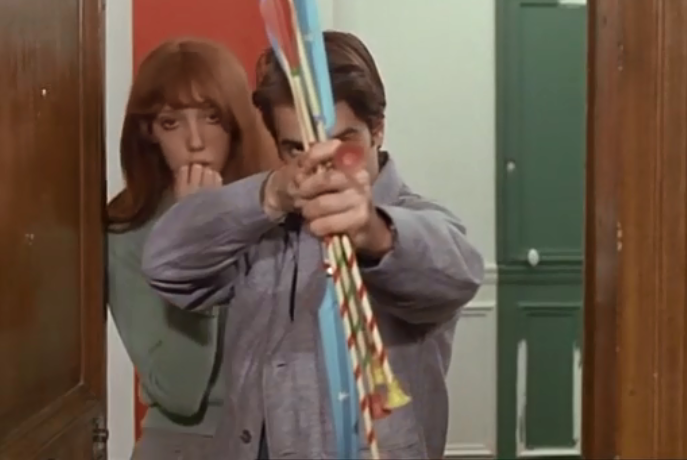

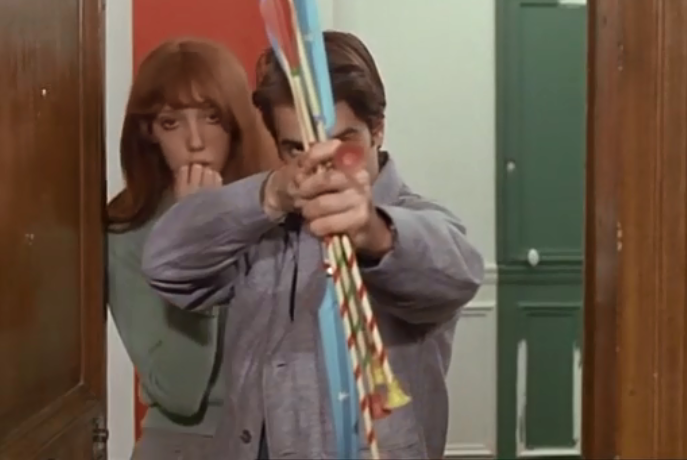

The Maoists of La Chinoise share Althusser’s rejection of the PCF, coupled with the conviction that Marxism should be understood as a practice—a guide to action and not a dogma. While their approach to investigation is often stilted and repeated by rote, the young revolutionaries are faithful to the Maoist approach of investigation. They draw truth from facts, replace vague ideas with clear images, discover the link between things and phenomena, ask what the relation is between different contradictions, discuss the weight of internal and external factors, and analyze the relation between objective and subjective factors in order to make a conjunctural analysis to advance the revolutionary cause. As Guillaume says while aiming his arrow: “How to unite Marxist-Leninist theory and the practice of revolution? There’s a well-known saying: It’s like shooting at a target. Just like aiming at the target, Marxism-Leninism must aim at revolution.”

d. Politicization of Culture

Throughout La Chinoise, Godard defends the view that a socialist revolution in an age of mass culture and capitalist affluence requires the politicization of culture. Naturally, Godard turns to Mao Zedong, who was concerned with the role of cultural politics in raising political consciousness amongst the masses. According to Mao, intellectuals and youth must politicize culture both before and after the revolution — particularly after, when a cultural revolution is needed against the compulsion of bourgeois culture which, if left unchecked, can lead to capitalist restoration.

The foundation of Mao’s views on culture can be found in On Contradiction, particularly his understanding of the different contradictions. Following his theory of shifting contradictions, Mao argued against the reigning Stalinist orthodoxy and mechanical materialism that reduced culture to the economic base. Instead, Mao argued that true Marxism recognized that the ideological superstructure could play a paramount role in impacting the economic base: “But it must also be admitted that in certain conditions… the creation and advocacy of revolutionary theory plays the principal and decisive role.” According to Mao’s Marxism, it was indeed possible for culture to take precedence over economics.

Mao fleshed out his cultural views during the 1942 Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art. Here, he argued against “art for art’s sake,” and instead opted for the politicization of culture, suggesting that intellectuals must use it as a weapon against the bourgeoisie:

If we had no literature and art even in the broadest and most ordinary sense, we could not carry on the revolutionary movement and win victory. Failure to recognize this is wrong. Furthermore, when we say that literature and art are subordinate to politics, we mean class politics, the politics of the masses, not the politics of a few so-called statesmen. Politics, whether revolutionary or counter-revolutionary, is the struggle of class against class, not the activity of a few individuals. The revolutionary struggle on the ideological and artistic fronts must be subordinate to the political struggle because only through politics can the needs of the class and the masses find expression in concentrated form.

It cannot be emphasized enough that, for Mao, the politicization of culture was considered essential for a communist victory. So how were intellectuals to play their proper role in the class struggle? For one, intellectuals need to shed their traditional habits of subservience to the ideas of the ruling class and stand with the people. However, it was not enough for intellectuals to merely speak about popular struggles, but in order to effectively convey those struggles, they had to adopt new forms of expression by making their ideas accessible.

In order to accomplish this goal, intellectuals and cultural workers could not just represent the masses in art and literature. They had to take an active part in their struggles by living among them. According to Mao, intellectuals must embrace a “mass style” and learn

the thoughts and feelings of our writers and artists should be fused with those of the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers. To achieve this fusion, they should conscientiously learn the language of the masses. How can you talk of literary and artistic creation if you find the very language of the masses largely incomprehensible?… If our writers and artists who come from the intelligentsia want their works to be well received by the masses, they must change and remould their thinking and their feelings. Without such a change, without such remoulding, they can do nothing well and will be misfits.

This was precisely what happened during the Yenan period when intellectuals flocked to the communist base area in order to fight and work alongside millions of ordinary people against the Japanese and for a new society. This was a clear example of the fusion of large segments of Chinese intelligentsia with the masses, an intelligentsia who were traditionally elitist, prided themselves on not performing manual labor, and disdained the peasantry (since entering communist-held territory meant risking imprisonment and death). While Mao’s theory of subordinating culture to politics can easily lead to abuse (as ended up being the case), there can be no doubt that it was effective as a tool of mass mobilization during the Chinese Revolution.

The Maoist understanding of culture and intellectualism is prevalent throughout La Chinoise, most symbolically in the name of the Maoist collective: Aden Arabie. The name of the collective was taken from the title of the most famous novel by communist Paul Nizan. Aden, Arabie is a semi-autobiographical story of a man who attempts to escape the suffocation of bourgeois life in France by traveling to the Middle East. Instead of liberation, he discovers that oppression exists there too. Ultimately there was no escape from the forces that crush humanity, but they must be fought without mercy or pity. As Nizan himself said:

There is nothing noble about this war. The adversaries in it are not equals: it is a struggle in which you will despise your enemies, you who want to be men. Will you be forever sitting at your catechism? You will have to refuse them a glass of water when they are dying: they pay notaries and priests to attend them in death… I will no longer be afraid to hate. I will no longer be ashamed to be fanatic. I owe them the worst: they all but destroyed me.

Nizan understood the reality of class struggle, and that one had to firmly choose sides and see that commitment through to the end.

For Maoists, Nizan was a kindred spirit since he was someone who took up his pen in the service of the revolution. As Sartre noted:

But now was the time to slash. It would be up to other men to sew the pieces together again. His was the pleasure of cheerfully ripping everything to shreds for the good of humanity. Everything suddenly took on weight, even words. He distrusted words, because they served bad masters, but everything changed when he was able to turn them against the enemy.

Nizan’s works were largely forgotten after his death, but they were rescued from oblivion in 1960 when Aden, Arabie was republished with an explosive preface by Sartre, selling twenty-four thousand copies upon its release. Sartre’s preface not only lifted Nizan’s reputation from purgatory, but presented an image of a rebellious, potent, and ferocious figure—all very in tune with the times. “[Nizan] issued a call to arms, to hatred. Class against class. With a patient and mortal enemy there can be no compromise: kill or be killed, there is nothing in between.”

e. Proletarianizing the Intellectuals

Like Nizan, the majority of the Maoists in La Chinoise come from intellectual and affluent backgrounds. Véronique is a philosophy student at the University of Paris-Nanterre and her boyfriend Guillaume is an actor. Serge Kirilov is a painter. Only two have proletarian credentials: Henri is a chemist, and his partner Yvonne is a young woman from the countryside. However, the cells largely live as bourgeois bohemians in an apartment borrowed from Véronique’s bourgeois relatives for the summer of 1967.

The characters spend their days studying Marxist texts, delivering lectures to each other, and figuring out how they can apply Maoism in order to make revolution. The atmosphere in the cell has an almost surreal quality; mornings are spent doing calisthenics to the chants of Maoist slogans, and revolutionary culture is calmly discussed in the evening while sipping tea from fine china. Classes and discussions are regularly held with guest speakers on a variety of topics, not unlike a revolutionary university. Although much of this display is comical and satirical, Godard’s portrayal of the Maoist cell is one of youthful rebels excited by the discovery of Marxist ideas and wedded to a newfound stridency that marked the times.

However, Aden Arabie is not a model of egalitarian relations. Despite the Maoist dictum that “women hold up half the sky,” Yvonne functions largely as the group’s maid. She brings her comrades tea, cleans the windows, and polishes their shoes. Yvonne even prostitutes on the side when the others cannot bring in money. While Véronique and Guillaume have a relatively sophisticated understanding of Maoist theory, Yvonne struggles with comprehending theory to a much greater extent than her comrades. Yvonne is isolated from the others during lectures and discussions, often residing in the background where she does menial chores that occupy her attention. For all of Aden Arabie’s calls about solidarity with the working class, the irony is that they are unable to connect with their own working-class roommate.

Despite the Maoists’ claim to be promoting a working-class culture that breaks with old values, their erstwhile comrade Henri still retains his bourgeois tastes (as demonstrated by his love of the Nicholas Ray film Johnny Guitar). Henri is the most pragmatic member of the group, the only cell member to vote against the creation of a new organization dedicated exclusively to combat through armed struggle and terror. This causes Henri to leave by himself, failing to take Yvonne with him. After leaving Aden Arabie, Godard spends a long time interviewing Henri, who makes many artful comments on the group as “too fanatical” and lacking concern with more practical issues (something expressed visually by him buttering his toast). Considering his pragmatic nature, Henri plans to join the French Communist Party once he has work in Besancon, or maybe East Germany. Henri’s character demonstrates the gap between the abstract rhetoric of Maoists and the concrete needs of non-revolutionary workers. Coincidentally, Henri himself resembles Ivan Shatov in Demons, whose character also deserted his leftist ideals.

It would be easy to ascribe the failure of the Aden Arabie cell as the fault of patronizing intellectuals unconcerned with the needs of the working class. An easy solution would be to say that the Maoists simply needed to dispense with intellectuals in favor of workers. However, all revolutionary movements need intellectuals—people with skills and training to develop a comprehensive critical analysis of a complex society and what its transformation entails.

Acknowledging this role for intellectuals is not denying agency from the oppressed, but rather, it recognizes that they play a vital role in constituting a fully formed collective revolutionary subject. Whether Marx, Lenin, or the Maoists of Aden Arabie, history has shown that intellectuals from the petty-bourgeois and even the ruling class can devote themselves to the cause of the oppressed, and they are critical to the initial formation of revolutionary organizations. For intellectuals who join the revolutionary movement, their choice entails enormous self-sacrifice and they must commit “class suicide” if they are to stay faithful to the goal of liberating working class. This requires a mutually transformative process of fusion of the ideas from the revolutionary intelligentsia with the working-class movement. The failed attempts do not negate this necessary step. Véronique herself recognizes her estrangement from the workers and the need to overcome it going forward: “I know I am cut off from the workers. After all, my family are bankers. I’ve always lived with them. None of that’s very clear. That’s exactly why I keep on studying to understand first and then to change, and then formulate a theory.”

While Godard’s La Chinoise was hailed for prophesying the burgeoning French Maoist movement that came into its own during the early 1970s, he was wrong in seeing a turn to armed struggle as the natural outcome of this radicalism (as did occur elsewhere in the sixties). After the student protests of 1968, thousands of student Maoists abandoned the universities and libraries and went to work with immigrants, shantytown dwellers, and rank-and-file factory workers. Their proletarianization became a rite of passage and self-sacrifice whereby Maoists could prove their revolutionary credentials, shed their bourgeois origins, and gain acceptance by the people. Maoist missionaries who had never previously performed manual labor had a difficult time adjusting to their new roles as workers. If revolutionary politics is to prove long-lasting, then this required undertaking the long and patient work of “educating the educators” and going to the people.

However, the strategy that the Aden Arabie cadre formulate is not to proletarianize themselves, but to close the universities through terror. Their armed actions resemble more individualistic acts of desperation than mass struggle called for by their own theory. A lengthy scene between Véronique (who is actually receiving her lines from Godard through an earpiece) and Francis Jeanson shows that the Maoists have no coherent strategy—their violence is divorced from the masses of working people, and they are attempting to invent a revolution through an act of will. Jeanson rightfully predicts their outcome: “You’re heading towards a dead-end.” In fact, that is precisely what happens. The assassination of the commissar leads to the death of an innocent bystander and causes their comrade Kirilov to take his own life. In the end, the armed campaign ends in a fiasco.

The ending of the film presents an ambiguous message. While Aden Arabie dissolves and the Maoists go their separate ways, revolutionary politics are not necessarily abandoned. As Véronique says: “A struggle for me and some comrades. On the other hand, I was wrong. I thought I’d made a leap forward. And I realized I’d made only the first timid step of a long march.” As evidenced by real life as much as in La Chinoise, the challenge of proletarianizing intellectuals, building a mass base, and finding the appropriate tactics for revolution is easier said than done.

f. Cultural Revolution

For Mao, the political role of culture only increased after the communist seizure of power in 1949. Mao argued that even though the old ruling classes were overthrown, the contradictions of socialism gave rise to new bourgeois elements. Despite the seizure of power and the establishment of a new economic base, class struggle continued:

In China, although socialist transformation has in the main been completed as regards the system of ownership, and although the large-scale, turbulent class struggles of the masses characteristic of times of revolution have in the main come to an end, there are still remnants of the overthrown landlord and comprador classes, there is still a bourgeoisie, and the remolding of the petty bourgeoisie has only just started. Class struggle is by no means over… The proletariat seeks to transform the world according to its own world outlook, and so does the bourgeoisie. In this respect, the question of which will win out, socialism or capitalism, is not really settled yet.

Following his earlier writings, Mao argued that the superstructure did not automatically change in response to the base, but there was a considerable lag as the old culture hangs on.

As time wore on, Mao recognized that those in the Chinese party and state who sought a return to capitalism needed to be combated. This culminated in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (as it was officially known), which launched in May 1966. The purpose of the Cultural Revolution was described in its opening manifesto as follows:

Although the bourgeoisie has been overthrown, it is still trying to use the old ideas, culture, customs and habits of the exploiting classes to corrupt the masses, capture their minds and endeavor to stage a comeback. The proletariat must do the exact opposite: it must meet head-on every challenge of the bourgeoisie in the ideological field and use the new ideas, culture, customs and habits of the proletariat to change the mental outlook of the whole of society. At present, our objective is to struggle against and overthrow those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic “authorities” and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art and all other parts of the superstructure not in correspondence with the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.

The Cultural Revolution was the culmination of Mao’s politicization of culture. The struggle on the cultural front would prove decisive in the proletariat’s battle against revisionism, and it would keep China on the socialist road.

Communists in France took note. Althusser, writing an anonymous article in Maoist Cahiers Marxistes-Léniniste (displayed prominently in La Chinoise) in November/December 1966 claimed that the Cultural Revolution was an “unprecedented” and “exceptional historical fact” that demanded a deep reflection on “Marxist theoretical principles.” Several years later, Althusser would go so far as to claim that the Cultural Revolution overcame the exhaustion of the Soviet model because it was

the only historically existing (left) “critique” of the fundamentals of the “Stalinian deviation” to be found—and which, moreover, is contemporary with this very deviation, and thus for the most part precedes the Twentieth Congress—is a concrete critique, one which exists in the facts, in the struggle, in the line, in the practices, their principles and their forms, of the Chinese Revolution. A silent critique, which speaks through its actions, the result of the political and ideological struggles of the Revolution, from the Long March to the Cultural Revolution and its results.

Indeed, the impact of the Cultural Revolution was felt far beyond China, something acknowledged in La Chinoise by Véronique, who quoted Althusser: “Exporting cultural revolt is impossible, as it belongs to China. But the theoretical lessons belong to all.”

When it came to carrying out the Cultural Revolution, Althusser argued that students played a vanguard role:

At the same time, the C.C.P. declares that these are mass youth organizations, principally urban youth, therefore made up for the most part of high school and university students, and that they are currently the vanguard of the movement. It is a factual state of affairs, but its political importance is clear. On the one hand, in fact, the teaching system in place for the education of the youth (we should not forget that school deeply marks men, even during periods of historical mutation), was in China a bastion of bourgeois and petit-bourgeois ideology. On the other hand, the youth, which has not experienced revolutionary struggles and wars, constitutes, in a socialist country, a very delicate matter, a place where the future is in large part played out.

The appeal of the vanguard role of students held an obvious appeal to not only Chinese Red Guards, but Althusser’s disciples and the Maoists of Aden Arabie.

According to Althusser, what was unprecedented about the Cultural Revolution was its recognition that “the ideological can become the strategic point at which everything gets decided. It is, then, in the ideological sphere that the crossroads is located. The future depends on the ideological. It is in the ideological class struggle that the fate (progress or regression) of a socialist country is played out.” For Althusser, the Cultural Revolution showed that “class struggle can continue quite virulently at the political level, and above all the ideological level, long after the more or less complete suppression of the economic bases of the property-owning classes in a socialist country.”

Therefore, it is fitting that the one act of violence that the Maoists do carry out is Véronique’s farcical assassination of the Soviet Minister of Culture, Mikhail Sholokhov (author of And Quiet Flows the Don and winner of the 1965 Nobel Prize in Literature). Sholokhov is an ideal target for those who think culture is a revolutionary weapon, since he represents a form of artistic revisionism which the Maoists believe needs to be smashed.

It is true that Maoism led the militants in La Chinoise into a cul-de-sac of Blanquist adventurism and burnout, but it also provided a revolutionary alternative to the PCF, offering a theoretical justification for students playing the vanguard role in the class struggle, as well as the necessity of ideological struggle against bourgeois and revisionist ideas and the promotion of revolutionary culture.

The Future Is Bright, the Road Is Torturous

Ironically, the Maoist students who inspired La Chinoise despised it. The Maoists thought Godard made them look foolish and stupid. Some believed that Godard was little better than a police agent and threatened to hold a “people’s tribunal” for him. One militant said that Godard “exploited a need for romanticism. He described a fanatical little group that has nothing Marxist-Leninist about it, which could be anarchist or fascist… It’s a film about bourgeois youth who have adopted a new disguise.” During May 1968, radical graffiti mocked Godard as “le plus con des suisses pro-Chinois” (translation: the biggest ass among the Swiss pro-Chinese).

Godard deserved better. While La Chinoise did poke fun of Maoism as radical chic and satirize revolutionary ideology as another fashion to be consumed, the film itself was a serious experiment at creating a new art form and grappling with how to make revolution. In a 1967 interview, Godard explained his motivations in producing La Chinoise:

Why La Chinoise? Because everywhere people are speaking about China. Whether it’s a question of oil, the housing crisis, or education, there is always the Chinese example. China proposes solutions that are unique… What distinguishes the Chinese Revolution and is also emblematic of the Cultural Revolution is Youth: the moral and scientific quest, free from prejudices. One can’t approve of all its forms… but this unprecedented cultural fact demands a minimum of attention, respect, and friendship.

Arguably, Maoism and the Cultural Revolution did not provide the answers that Godard believed they did. However, the questions raised by Godard on art and communist politics are far from superficial, but remain ones with which every artist and revolutionary must grapple with.