The failure of the German left to unite against Hitler is often used as a warning to those who fail to build unity with liberals in order to stop the far-right. Why did the German Communists and Social-Democrats not unite against the Nazis? John K argues not all blame can be placed on the Communists for their failure to build a proper united front, as their uneasy relationship with the Social-Democrats was based on the treacherous behavior of the Social-Democrats themselves. We publish this despite believing that the reductionist and ultra-left politics promoted by the Stalin-dominated Comintern deserve heavy critique and that ultimately the party made major strategic and political errors in leading the working class with its lack of democratic flexibility and exercise.

On the night of February 27th, 1933 in Nazi Germany, not even one month after Adolf Hitler became Reich Chancellor, the Reichstag, home of Germany’s parliament, was destroyed in a fire. This fire, an act of arson, was a pivotal and tragic moment for the German left. In Hitler’s “Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the People and State,” issued the following day “as a defensive measure against Communist Acts of violence endangering the state,” the Communists were blamed for the terrorist act.1

With this decree, Hitler began a process that effectively crushed any and all potential political resistance to the Nazi regime. The left, not just the German Communist Party, but also the German Socialist Party which had enjoyed national prominence during the Weimar Republic years, was silenced. In a matter of months following the decree, Germany’s political left was assaulted by the Nazi state, and its leaders sent to Concentration Camps or into exile. In the months and years leading up to the Nazi triumph over the left, a unified right developed in Germany while the left remained divided. In particular, the Communists ( the Kommunistiche Partei Deutschlands, or KPD) was never willing to work in an alliance with the Social-Democrats ( the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands or SPD). While both parties drew on Marxism for their ideological platform, the more radical KPD considered the SPD to be a social fascist enemy. Thus, while the right was unifying behind the Nazis during the 1928-1933 period, the KPD devoted its resources to fighting both the Social-Democrats and the Nazis.

Why did the KPD adopt such a course of action? Many scholars, such as Beatrix Herlemann argue that the KPD had evolved, by the late 1920s, into a Stalinist party whose interests were subservient to the orders of the Communist International. As Herlemann argues, the KPD “followed without reservation the Comintern’s political line – namely the “social fascism” thesis launched in 1928 to 1929, by which the KPD directed its entire force toward the fight against social democracy and enormously neglected the growing danger of National Socialism.”2 The view taken by Herlemann is not without merit. The KPD leadership did advocate action against the SPD, and even reached out to Nazi rank-and-file workers for an alliance against the SPD Union leadership.3

It is wrong, however, to assume that the KPD devoted all of its resources to a fight against the SPD and neglected the Nazi threat. On the contrary, most of the political violence practiced by the KPD during 1928-1933 was directed against the Nazis, not the Socialists. It is also incorrect to assume that the divide between the KPD and the SPD was entirely motivated by the orders of the Comintern. Certainly, the Comintern heavily influenced the KPD’s course of action, but deep divisions had existed between the KPD and the SPD from the very day that the KPD became a political entity. Further, the differences between the two parties were not merely ideological. KPD and SPD membership came from different economic spheres, they lived in different neighborhoods, and they experienced the Weimar Republic in different ways. The SPD, for much of the Republic’s existence, was one of the main parties of government. When the KPD accused the SPD of Social Fascism, they were not targeting another radical left party; they were focusing their criticisms on one of the most powerful political entities in the Republic. Related to this, the SPD had in its position of power pursued repressive tactics against the KPD. Thus, the KPD’s view of the SPD as social fascists was not merely the result of ideological dogmatism but was in fact shaped by the actual experience of the KPD in the Weimar Republic.

To fully understand the schism between the KPD and the SPD, one must turn to the fall of Imperial Germany at the end of the First World War in 1918, and the revolutionary period that followed, before turning to the formation of the Weimar Republic in 1919. Before the First World War, the Marxist left was united as the SPD. By the time the Great War began, the SPD was the most popular political party in Germany and had gained more seats than any other political party in the Reichstag. The unified SPD, however, was internally divided between those who wanted to achieve the party’s ideological goals through participation in the government and those who wanted to actively pursue Revolution. The tension between these two groups erupted after SPD delegates to the Reichstag, representing the more moderate wing of the party, voted unanimously in favor of Germany entering the First World War. The more radical elements of the party that opposed this action, who were eventually cast out of the SPD in 1917, became the genesis for the KPD.

As Revolution erupted in Germany once it became clear that the war was lost, the more radical group of Marxists, calling themselves Spartacus League, issued their November 26th Manifesto declaring that “the revolution has made its entry into Germany. The masses of the soldier, who for four years were driven to the slaughterhouse… and the masses of workers… have revolted.”4 While the Spartacus League declared a revolution, the majority of the SPD continued to work with the crumbling German State. The split between Germany’s left, apparent with the issuance of the Spartacus Leagues Manifesto, became final when Marxist leader Rosa Luxemburg authored the “Founding Manifesto of the Communist Party of Germany, [KPD].” In the manifesto, Luxemburg declared “that it is time to shake ourselves [the KPD] free of the views that have guided the official policy of the German social democracy down to our own day, of the views that share responsibility for what happened on August 4, 1914.”5 Luxemburg further asserted that “what passed officially for Marxism [in the SPD] became a cloak for all possible kinds of opportunism, for persistent shirking of the revolutionary class struggle, for every conceivable half measure.”6

As can be seen, it was not simply the orders of the Communist International that spurred the KPD into opposing the SPD. The Party’s very birth came as a result of profound disagreements within the German left: disagreements that were not simply theoretical, but deeply political in the form of the more moderate elements of the SPD’s support for German involvement in the First World War. During the revolutionary period and the early Weimar Republic years, the KPD also experienced oppression and violence as a result of SPD actions. Historian Eve Rosenhaft notes that after the Weimar Republic was established, the radical left, including the KPD revolted, “demanding… socialist programmes…. Freikorps and paramilitary police under Social Democratic administration put down the disturbances in two months of bloody fighting.”7 Historian Eric D. Weitz similarly notes that “the SPD’s alliance with the police, the army, and the employers undermined its popular support, which redounded in part to the benefit of the KPD.”8 Of equal importance is Rosenhaft’s assessment that “the political division between the Communists and the Social Democrats that had emerged between 1917 and 1919 was reinforced by increasing divergences between the interests of different sections of the working class.” 9 The wealthier, more skilled proletariat joined the SPD while semi-skilled laborers became the rank-and-file members of the KPD. Thus, when one examines the later actions of the KPD’s declaration of the SPD as Social Fascists, one must understand that the reasoning did not suddenly develop as a result of the Comintern’s policy directives, but that the KPD had actually experienced oppression from the SPD. The KPD had evidence of the SPD working with the right and conceding fundamental goals of socialism, whereas it had yet to experience the far more brutal repression of the Nazis.

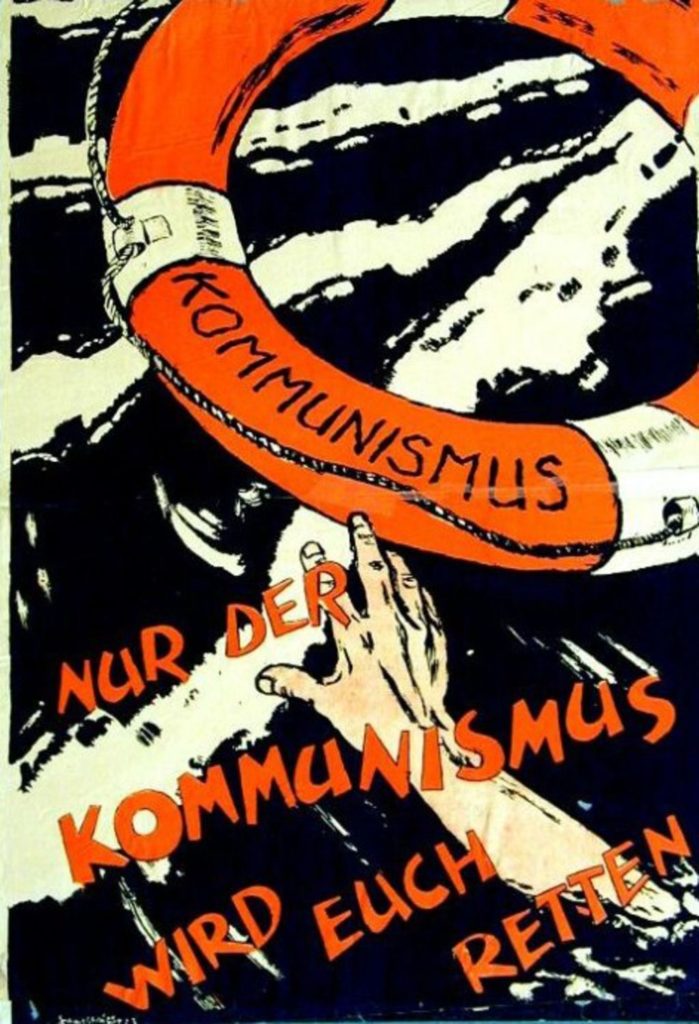

The 1929 Program of the Communist International, issued as the Nazis were beginning to gain significant national prominence, outlined the Social Fascism concept that would prevent the KPD from uniting with the SPD in opposition to the Nazis. The program detailed the attempts of the Proletariat to ferment revolution in the wake of the First World War, which led to the creation of the USSR but also the defeat of the Communist left in a number of other countries, such as Germany. The program declared that “these defeats were primarily due to the treacherous tactics of the social democratic and reformist trade union leaders” as well as the fact that Communism was just starting to become a popular political ideology.10 The Comintern further argued that “Fascism strives to permeate the working class by recruiting the most backward strata of workers to its ranks by playing upon their discontent, by taking advantage of the inaction of social democracy.”11 The Comintern also asserted that “in the process of development social democracy reveals fascist tendencies which, however does not prevent it…[in other situations from operating as] an opposition party [to the bourgeois].”12

To further understand the position taken by the KPD against the SPD, Ernst Thälmann’s 1932 speech “The SPD and NSDAP are Twins” reveals how the KPD leadership envisioned its struggle against fascism in all forms. Thälmann’s incendiary speech declared that “joint negotiations between the KPD and the SPD… there are none! There will be none!.” 13 This was not to say that the KPD did not recognize the Nazi threat, as Thälmann articulated that “KPD strategy directs the main blow against social democracy, without thereby weakening the struggle against Hitler’s fascism; [KPD] strategy creates the very preconditions of an effective opposition to Hitler’s fascism precisely in its direction of the main blow against social democracy.”14 It is imperative to recognize, though, that the KPD only advocated the blow against the SPD leadership. As Thälmann argued, The KPD’s policy envisioned, the creation of a “revolutionary United Front policy… [that mobilized the masses from below through] the systematic, patient and comradely persuasion of the Social Democratic, Christian and even National Socialist workers to forsake their traitorous leaders.”15

Thus, KPD invective was not aimed at the average member of the SPD, but at its leaders. The KPD was also not devoting resources to fighting Social Democracy instead of fighting Nazism. Rather, it was pursuing a strategy in which it believed that the defeat of Fascism would only be possible through the unification of the proletariat into one Revolutionary mass. This helps explains the KPD leadership’s focus on attacking the SPD rather than completely focusing its energies on Hitler. The KPD believed that what it viewed as a socially fascist SPD was dangerous because it claimed to advocate socialist policies while in reality, it subsumed a large portion of the proletariat into supporting a political entity that actually benefitted the bourgeois. This prevented the proletarian class from achieving true Marxist socialism. KPD leadership devoted its energies to attacking the SPD more so than the NSDAP because the Nazis were an overtly fascist group, whereas the SPD, in the KPD’s view, furthered fascism under the auspices of a claimed leftist ideology. To the KPD, the SPD was an insidious threat that needed to be exposed to all of the working class to see. The KPD did, in fact, want a united left or unified front to fight the fascists. It just did not want to unite with the leaders of the leftist parties. Instead it envisioned a United Front of the masses that would seek revolution to secure the goals of the proletariat, also termed a “united front from below”.

While the KPD leadership devoted much of its rhetorical attack towards the SPD rather than the Nazis, the same can not be said of the actions of the rank-and-file party membership. Between 1928-1933 the party primarily practiced non-violent opposition towards the SPD while political violence was reserved for the NSDAP and its paramilitary SA stormtroopers. Thus, Hearlmann’s contention that the KPD neglected the growing threat of Nazism only holds true if one relegates themselves to examining the documents of the KPD leadership and the Comintern. The reality is that during the 1928-1933 time period, as Eve Rosenhaft shows in her study of the KPD’s use of political violence during this period, the KPD pursued a “wehrhafter Kampf [against the SA] as a fight to maintain or recover actual power in the neighborhoods.”16 As stated before, the KPD and the SPD attracted different groups amongst the proletariat. In the harsh final years of the Depression-era Weimar, though, the Nazis and the KPD were fighting for the hearts and minds of the unemployed and unskilled segments of the proletariat. In cities such as Berlin, this translated to street-fighting between the KPD and SA over control of the neighborhoods these segments of the working class lived in. As Rosenhaft so eloquently puts it, “the terror of the SA… [was] a threat specifically directed against working-class radicalism, [that] evoked a response with the weapons familiar to the neighborhood [violence].”17 Historian Dirk Schumann largely concurs with Rosenhaft’s assessment of the KPD’s use of political violence, noting that “while Communists and Social Democrat’s hardly ever clashed in physical confrontations, both appeared on the scene as enemies of the right-wing groups.”18 Thus, while the KPD leadership advocated opposition to the SPD and the Nazis. The reality on the streets, where political violence served as a potent form of expression for the proletariat, was that the left devoted its energies to fighting the right rather than each other.

In the end, the policies of the KPD failed. What came about in 1933 was not the revolution of the proletarian masses, but rather the Nazi seizure of power and the twelve-year reign of Adolf Hitler. The united revolutionary front against the fascists never materialized and the KPD, along with the rest of the German left, was subjected to repression, exile, and imprisonment. Ernst Thälmann, when he gave his “The SDP and the NSDAP are twins” speech in 1932, did not have the benefit of knowing that twelve years later he would die in the Buchenwald concentration camp. In the final years of the Weimar Republic, the KPD leadership and the Comintern that helped shape its ideology and actions were unaware of what would soon occur. What the KPD did have, however, was the memory of its experiences during the Revolutionary period following Imperial Germany’s collapse, the everyday experience of an SPD that did not pursue revolutionary Marxist goals, and a party membership that was suffering under the hardships of the Weimar Republic, particularly during the depression years.

In hindsight, the Nazis were clearly the greater threat, but the KPD had experienced more than a decade of an SPD that had, from the Communist’s perspective, disregarded and undermined the Revolutionary goals of the party. The KPD may have made a terrible miscalculation in identifying its threats, but that miscalculation was not the result of ideological dogmatism, but rather experience. The idea that the KPD could have simply pursued a unified front with SPD leadership ignores the very circumstances and reasons for the party’s existence in the first place. Furthermore, the KPD did not devote all of its energy to combatting social fascism while ignoring the threat of the Nazis. The reality of the political violence experienced during the Weimar Republics final years demonstrates that the KPD and the SPD practiced violence, not against each other, but against the Nazis and the right.

Ultimately, the one form of political opposition -violence- which both the SPD and the KPD used against the NSDAP, in part led to the destabilization of the Weimar Republic, which allowed for the Nazis to be elected into office. As Dirk Schuman notes, “National Socialism stood in a tradition of bourgeois-national opposition to the Weimar Republic, which it radicalized so successfully against the backdrop of crisis that voters flocked to it in large numbers.”19 If the KPD and the SPD had presented a united front, would it have made much difference in the end? It was not the division between the left that caused the Depression or spurred the political violence of the SA. In light of the fact that both of these conditions would have existed even if the SPD and KPD had presented a truly united front against Nazism, it is worth questioning what this united front would have achieved. After all, the Nazis did not come to power in a violent revolution. Though violence surrounded their rise, the Nazis were democratically elected into office. Because of their ideology, the KPD and the SPD were permanently parties of the working class. A united left might have allowed for the KPD to devote its full energies to attacking Nazism, but in the end, the only ones that would have listened would have been the proletariat. Would this really have prevented the Nazi electoral victory?

In light of all this, how should KPD actions during 1928-1933 be judged? In terms of preventing fascism, the policy was an unequivocal failure. With regards to the KPD’s fight against what it perceived to be the social fascism of the SPD, though, the evidence suggests that this policy should not be judged too harshly. While it failed to recognize the events that would eventually occur, it was grounded in the KPD experience in Germany and was not simply the result of the dictates of the Comintern. KPD resistance to the SPD was elemental to the very existence of the party. Not only that, but the KPD had actually experienced repression from the SPD. Thus, while the policy failed to recognize the true threat of the Nazis, it should not be viewed as patently ridiculous. The failure of the left to form a United Front also did not prevent the KPD and the SPD from actively fighting the Nazis in the streets. While this political violence only increased electoral support for the Nazis, it was amongst groups such as the Bourgeois-Nationalists, that actively despised the left and everything it stood for.