Translation and introduction by Ian Scott Horst. Buy a copy of his new book on Ethiopia, ‘Like Ho Chi Minh! Like Che Guevara!’ here.

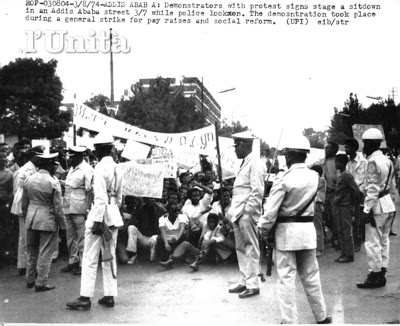

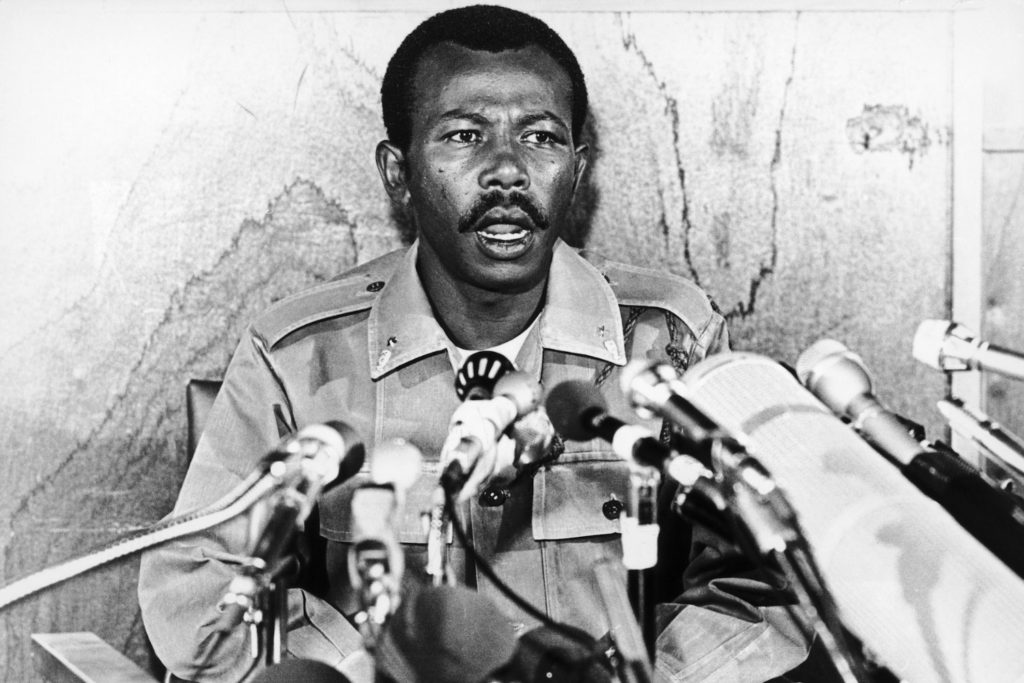

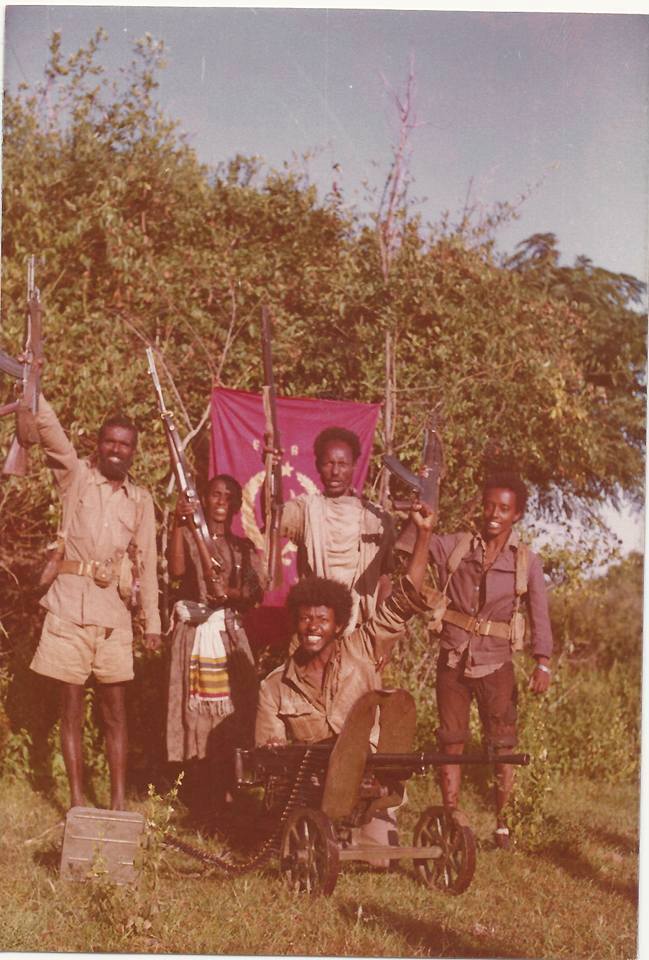

The following article was published by the European office of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party in Rome in 1980. It appeared in the first and only issue of the Ethiopian Marxist Review, an English-language periodical the EPRP’s foreign section hoped would engage the world left. In 1980 that left was then largely (and unfortunately) singing the praises of Mengistu Haile Mariam, the military chief of state and leader of the Derg, the military organization that had governed Ethiopia since the revolutionary year of 1974. Sadly, the Review took several years to become a reality after it was first envisioned by the Party, and by 1980 the EPRP’s resistance to the military regime was in deep retreat, having suffered massive loss of life during the period of the so-called Red Terror. The EMR received little exposure and made little impact. At its 1984 Congress held in a remote rural area of Ethiopia, EPRP would in fact largely jettison explicit Marxism-Leninism as a guiding ideology. But the contents of the Review are fascinating, well-written, and largely devoid of the stilted prose and dogmatism that marred so much leftist literature in the 1970s.

One of the most interesting and important articles from the Review is a direct challenge to the many leftists, African or otherwise, who gutted Marxist theory in order to rationalize and excuse regimes that claimed a mantle of socialism made unrecognizable to those revolutionaries who once envisioned socialism as a form of radical mass democracy. The article is credited to one “F. Gitwen”; it can now be revealed that the moniker is a pseudonym employed by Iyasou Alemayehu, one of the founders of the EPRP (and today still one of the post-Marxist party’s leaders in exile). I presented excerpts of this important piece in the concluding chapter of my new book, Like Ho Chi Minh! Like Che Guevara! The Revolutionary Left in Ethiopia, 1969–1979, being published in September 2020 by the Paris-based Foreign Languages Press. I am extremely happy to present the entire piece to today’s Cosmonaut readers. While the era of the left-talking military regime has faded and thus the immediate circumstances of this article are somewhat dated, the subject it tackles remains profoundly relevant as Africa — today a battlefield in a new cold war between the United States and China — confronts the failures of post-colonial states to empower the great masses of African people in controlling their own destinies. It is also a profound rebuttal to the apologias of those leftists who deny the agency of an African proletariat in favor of military men or bureaucrats with a taste for leftist props. Beyond its relevance to African specifics, the article’s discussion of bourgeois democracy — something now seeming to fall out of global favor in the era of neoliberalism, rising fascism, and an apocalyptic pandemic — is relevant and useful in understanding the relationship of class and class struggle to the political forms that rule our lives.

I have corrected a few typos and Americanized spelling and typographic conventions but not otherwise edited this text from the 1980 original.

In many parts of Africa where the word “socialism” has more or less become a shibboleth, Lenin’s affirmation that “proletarian democracy is a million times more democratic than any bourgeois democracy” seems to have a bizarre ring to it. In fact, it is precisely in those African countries where the regimes claim adherence to “Marxism-Leninism” that one notices the virtual absence of democracy and the existence of rule by terror. In countries ruled by such regimes and actually in greater parts of Africa, the ruling classes consider “democracy” as a tainted word, “un-African and western” and, at best, as “the unrealistic demand of hyphenated or De-Africanized intellectuals.”

The negation of democracy revolves around two basic premises. The first one considers Africa’s tasks as being one of “coming out of economic backwardness” and this is assumed to be incompatible with notions of democracy which “sap discipline,” “scatter the nation’s forces” and “invite anarchy.” In such cases, democracy is counter-posed to economic development and rejected consequently as a “luxury that the African masses cannot afford.” The second premise attributes to socialism the function of negating democracy, the limitations of democracy within bourgeois society are taken to exclusively define democracy, and, consequently, a rejection of what is termed as “fake bourgeois democracy” becomes in reality a rejection of “democracy as a whole.” In such cases, the declared attempt to establish a “socialist” society is deemed incompatible with all notions of democracy, and the “need for the iron fist of the proletarian dictatorship” is invoked in order to justify the extensive repression which, as in Ethiopia, claims the proletariat as its main and favorite victim. Official socialism in Africa, whether it takes the label “African” or “scientific” to define itself, is basically authoritarian and professedly anti-democratic.

The struggle waged by African revolutionary forces for democracy, be this within the framework of a general struggle for socialism or within limited perspectives, cannot revolve around a banal defense of democracy in general. The essence of the question itself lies in posing the question in the concrete, within the framework of the class struggle and social development of the given society. Admittedly, the level of development of each country and the class struggle within each demonstrate different stages and features. However, a general look, with all the apparent drawbacks of such generalizations, discloses that Africa’s problem is not so much the existence of “limited western type of democracy”—the problem lies in the absence of even a limited variety of democracy. For, a closer look at some of the countries which claim to have adopted parliamentary forms of rule or western-type bourgeois constitutions reveals that this adoption remains virtually at the formal level, with no actual democratic guarantees and with a presidential system giving wide executive and legislative powers to the president. The existing political parties, in many cases the president’s party, being caricatures of political parties within the western bourgeois republics.

The whole situation is entwined with the level of social development, with the fact that the majority of African societies are just emerging from various degrees of pre-capitalist relations and being integrated into the fold of international capitalism. The process of integration is itself a complex one, the imperialist domination militating against the emergence of a national bourgeoisie in the classical sense, and the introduction of capitalism in this form perpetuating, in a weak and distorted form, the old relation with all the backwardness involved. The absence of an “independent” bourgeoisie and the impossibility of an independent capitalist development militates against the existence of bourgeois democracy even in its restricted form. What exists is in fact a caricature of bourgeois democracy that takes the limitations of the latter as virtual excesses and, instead, establishes an all-embracing authoritarian rule.

The struggle for democracy in Africa cannot be equated with a yearning for bourgeois democracy per se. But, at the same time it is also indisputable that, with all its limitations, bourgeois democracy represents an advance over feudalism or absolutist rule. While it is true that proletarian democracy is qualitatively higher and broader than any type of bourgeois democracy, it is also a fact that bourgeois democracy represents an advance over feudalism. Hence the argument that bourgeois democracy is “bourgeois” and “totally unimportant” for those struggling for socialism in Africa is wrong and exhibits the infantilism castigated by Lenin in his celebrated text: Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder. Africa doesn’t necessarily need to pass through capitalism to arrive at socialism, but Africa necessarily needs democracy to get anywhere near socialism.

The struggle for socialism requires and is significantly assisted by the democratization of society. The more democratic concessions the proletariat and the masses wrest from the ruling classes, the more the situation improves for the struggle towards socialism, for carrying out the fight to get rid of the limitations imposed by the bourgeoisie on democracy. This is why Lenin affirmed that the bourgeois revolution is not only highly advantageous to the proletariat but is also absolutely necessary in the interest of the proletariat. The proletariat’s attitude to the bourgeois-democratic revolution is summed up by Lenin as follows:

“…The very position the bourgeoisie holds as a class in capitalist society inevitably leads to its inconsistency in a democratic revolution. The very position the proletariat holds as a class compels it to be consistently democratic. The bourgeoisie looks backwards in fear of democratic progress which threatens to strengthen the proletariat. The proletariat has nothing to lose but its chains, but with the aid of democratism it has the whole world to win. That is why the more consistent the bourgeois revolution is in achieving its democratic transformations, the less it will limit itself to what is of advantage exclusively to the bourgeoisie. The more consistent the bourgeois revolution, the more does it guarantee the proletariat and the peasantry the benefits accruing from the democratic revolution.”

The fashionable argument amongst the apologists of existing African regimes is that the struggle in Africa for democratic rights (freedom of the press, of association, etc.) is either “bourgeois!” (in which case “reactionary”) or “elitist.” The tragedy is that this type of argument is also echoed by certain African left-wing groups in an ironic reproduction of the infantile “leftists” of Lenin’s time: “we are struggling for socialism and hence it does not interest us to struggle for democratic rights under the bourgeois system.” The argument that bourgeois democracy is limited should at least be justifiably presented within a context of existing socialist democracy. In the concrete context of Africa, bourgeois democracy is absent and thus the rejection of it by the regimes and their apologists amounts to no more than a rationalization of authoritarian rule. As for the socialist struggle, it is, as Lenin pointed out, effectively assisted by the democratization of society.

Marxists do know for sure that “bourgeois democracy and the parliamentary system are so organized that it is the mass of working people who are kept farthest away from the machinery of government.” But the Marxist criticism of bourgeois democracy is directed not at democracy per se but at its limited and restricted nature under bourgeois rule. In the criticism, there is no underlying exaltation of “pure democracy.” So long as classes exist, it is not possible to speak of “pure democracy,” says Lenin in his celebrated polemics against Kautsky. And even in ancient Greece, despite Nyerere’s assertion that pure democracy existed, what was evident was not so much the rule of the people (demos) but, as Thucydides said of Athens, the rule by “the greatest citizens.” If Marxism lays bare the fallacy of “pure democracy” and situates the question within its relations to classes and class struggle (“under communism democracy will itself wither away and will not turn into ‘pure democracy’”—Lenin), the criticism of bourgeois democracy does not fall within infantile limitations. The question is not one of rejecting the forms of bourgeois democracy (parliament and the like) but of rejecting the basis of the democracy envisaged by the bourgeoisie and of asserting in its place a qualitatively higher and different form of democracy. To the argument of Kautsky projecting parliament as “the master of government,” Lenin countered with the people as “masters of parliament” — in other words the suppression of parliament as such. But this position bases itself on a fundamental premise involving the question of power and the establishment of a new order. The suppression of parliaments and constitutions in several African countries does not fall within the category of a revolutionary action as it is not an art directed at eliminating the limitations of bourgeois democracy. On the contrary, the suppression manifests the regime’s unwillingness and incapacity even to tolerate the limited rights granted by bourgeois democracy, it is a recourse to blindly authoritarian rule. The “people as masters of parliament” means the abolition of the separation of power from the masses, it means the concrete assertion of the people as the holders of power and the end of the subordination to it. What is at issue is thus not the mere change of forms or a quantitative problem — it is the destruction of the old order and state (“the mechanisms of the bourgeois state exclude and squeeze out the poor from politics, from active participation in democracy”) and the replacement of the institutions of the old order by other institutions of a fundamentally different order. Hence, a seizure of power which is accompanied by the preservation of the state and old order cannot surpass or come out of the limitations of bourgeois democracy, and, as many African cases show, will actually exhibit more retrograde and repressive institutions and rule.

The critics of the struggle for democracy in Africa sever Lenin and Marx from the above fundamental points and seek to legitimize their anti-democratic actions of criticism [of] bourgeois democracy. But a genuine criticism of bourgeois democracy cannot be viewed outside of a genuine struggle for socialism, i.e. a real effort to eliminate the limitations of bourgeois democracy establishing a fundamentally different type of democracy, proletarian democracy. A seizure of power or even a revolution that perpetuates the separation of the masses from power and their dependence on the State cannot be considered socialist or will not, at least realize the transition toward socialism.

In many countries in Africa, the struggle for democracy is being waged in a situation in which bourgeois democracy as practiced in the developed countries of Europe and America does not exist. The struggle is waged in a situation in which the winning of even limited democratic rights becomes a significant victory. The winning of bourgeois-democratic rights represents a contribution to the struggle for socialism, overcoming the existing practice of total censorship and prohibition of organization opens up broader possibilities for revolutionary struggles and helps to eliminate the limitations imposed by clandestine struggle. The struggle cannot be waged as part of a strategic belief that one can gain concessions from the ruling class and through this win over a majority in parliament and … institute fundamental changes. This is nothing but a reformist illusion. The struggle for bourgeois-democratic freedom is waged in the correct perspective only when posed as a stepping stone, as a useful and necessary step for the proletariat’s struggle for power, for the destruction of the State and the creation of a new society. Consequently, this assumes that there should be no continental or economic indexes set for prescribing broad democracy for one people and limited ones for others. For, there are those who call themselves “communist” but who do not hesitate to declare that while demanding broad democracy may be justifiable in Europe, such is not the case for Africans and others from the so-called “underdeveloped” countries.

Admittedly, the path to be traversed by each country towards socialism will differ, however, it is incongruous to assert that there can be any transition to socialism without the existence of broad democracy for the people. Santiago Carrillo, the leader of the Spanish Communist Party, states in his book, Euro-communism and the State, that to demand pluralism in countries like Vietnam is like braying at the moon. This is not because Carrillo considers the demand unrealizable, but it is because he considers such a demand is not relevant for the masses of these countries due to their level of development. Carrillo’s position has also been echoed by others who justify the anti-democratic actions of the juntas in Africa by asserting that though these acts may be considered undemocratic and paternalistic in Europe they are not so in Africa. It is a vicious argument that victimizes the African masses — their economic level of development, which is itself linked to the existing state of oppression and exploitation, is invoked to deny them the right to demand broad democratic rights. While it is true that the level of democracy existing in a given country is determined by a combination of factors (level of development, class struggle, etc.), there is absolutely no justification for severing democracy from socialism when the latter is applied to Third World countries. In fact, the demand for advanced or broad democracy is as legitimate in Gambia as it is in Spain and as relevant in Ethiopia as it is in Europe, despite the existing differences in the degree of development on the socio-economic level. If freedom and democracy are not to be viewed through racially-tinted glasses, the struggle for democracy waged in Africa, the opposition to unique parties, the rejection of despotic and paternalistic rule, etc. … are more than justified. As to economic development, while it is true that men are the products of circumstances, it is all the more true, as Marx explained, that circumstances are changed by men. The way out of economic backwardness is via a revolution assuring the masses power and a qualitatively different kind of democracy. In other words, democracy is not only necessary for the transition towards socialism, it is also indispensable for the success of the struggle of the proletariat to assume power. This is why the struggle for democracy assumes its importance, this is why in waging the revolutionary struggle it is repeatedly emphasized that the revolutionary forces must themselves have democratic structures, working-methods and the alternative organization of the masses (in clandestinity, in the liberated areas, etc.) must manifest the existence and practice of democracy and the exercise of power by the masses themselves. Viewed from this angle, many of the movements waging armed struggle in Africa are found lacking — their opposition to the antidemocratic regimes is not expressed by an alternative different democratic practice and, in fact, in some so-called “liberated areas” the only change for the masses is the change in the identity of the oppressors. Like the regimes, the movements also invoke “revolution” and “socialism” to stifle democracy and the militarist bent is assisted by the dominant form of the struggle being waged.

The struggle for democracy in Africa is also an affirmation of the existence of classes and class struggle in Africa. In this way, it is a clear rejection of the views which project pre-colonial or traditional Africa as essentially being devoid of class differences and antagonisms. Though the 1960s’ brand of “Africanists” who denied the existence of classes in Africa has become more or less extinct, the recognition of the class divisions pertaining in Africa has not been accompanied by a consistent admission of the reality of class struggle. The link between the denial of the reality of class struggle and democracy is highlighted by the position of many African regimes and their apologists vis a vis the organization of political parties and the right of dissent and assembly/association. In the rationale presented to defend the unique party and to reject pluralism or the right to freely organize, there appears a firm rejection of class struggle.

Many years back, one of the fervent defenders of the unique party system, Madeira Keita, put it as follows:

“We think that there are forms of democracy without political parties. We also state that if a political party is the political expression of a class and the class itself represents interests, we cannot affirm that the African society is without classes. But we state that the differentiation of classes in Africa does not imply diversification of interests let alone opposition of interests.”

Thus, the unique party, whether identified as a mass party or a patron one, becomes an identification or actualization of the “oneness of the community” and the mesmerism of the name of the people and the ‘oneness of the community’ is invoked to oppose all attempts to form other parties. And, as Sekou Touré stated in 1963, the unique party is identified with the people and the regime has the virtue of being the expression of the people within a party. The arguments of the advocates of the unique party, ranging from M. Keita to Sekou Touré, Nyerere, and Kaunda, revolve grosso mondo around the denial of class antagonisms, an invocation of a non-existent ‘oneness’ of the people as a whole, and the need for “unity” to overcome “backwardness and other enemies.” The denial of the right to organize parties is only an aspect of the absence of democracy but it emphasizes the problem. While for those like Madeira Keita, democracy does not imply the plurality of parties (the issue is actually as to whether the denial of the right to organize implies a restriction of the right of the people, a negation of democracy), for Nyerere, and others like him, the foundations of democracy are more firm if there is one party (“identified with the nation as a whole”) rather than many (“which represent only a section of the community”). For the latter, the existence of several parties in a country, as in the Congo of the 1960s, leads to division and anarchy. Nyerere’s argument not only mixes up cause and effect — parties are the political expression of existing class struggles not vice versa — but is not supported by empirical observation: the one-party states are, if not more, at least as trouble-prone and as problem-ridden as the ones with several parties.

The identification of the unique party with the whole nation automatically makes all attempts to exercise the right to association “subversive.” It also opens wide the door for apologetic positions vis a vis the repression unleashed by the regimes in such countries against the opposition which is ipso facto considered “anti-national” and “divisive.” Writing about the one-party government in Ivory Coast, Zolberg put forward a striking apology of the repressive actions of the state in the following manner:

“Sanctions (of coercion), however severe, are usually temporary; and coercion is not used methodically to induce a climate of terror. Relationships between rulers and dissenters retain the air of a family quarrel, followed by grand reconciliations when the crisis is over.”

A “family quarrel” resulting in massacres, a “grand reconciliation” that is consumed with corpses or presumed from the absence of opposition due to repression — it is bizarre to say the least, and very characteristic of the apologists of the repressive African regimes.

The resort to sanctified arguments about the unity of the community, the absence of diverse, let alone antagonistic, interests is a practice of both the exponents of “African socialism” and of the declared adherents of “scientific socialism.” The basic approach in both cases is “productionist”: dissent or opposition is ostracized under the guise of the need for unity to combat backwardness and t come out of the mire of underdevelopment. Thus, the whole people, from the president downwards will for one regiment of disciplined citizens (Nkrumah) and the unique party “assures discipline by molding the amorphous collection of people into an organic and dedicated body of men and women sharing an identical view of human society.” The party accomplishes this task by “curbing those social groups struggling for influence” and by impeding them from “unleashing class warfare inimical to the collective interests of the nation.” And this collective interest is expressed, as Senghor maintains, by the State, which means that obedience to the State and loyalty to its policies is the “necessary duty of the responsible citizen.”

The regimes that claim adherence to “socialism” of the Moscow variety have other justifications in their arsenal. They resort to the fallacious Soviet conception of “the party of the whole people” (that dissent in the USSR is considered a schizophrenic sickness is quite indicative of the consequences of this conception) and conjure up the name of the proletariat, whose name and power they have actually usurped, in order to raise the spectre of proletarian dictatorship. The problem is not solely the fact that the dictatorship being exercised is not that of the proletariat (be it in Ethiopia, Angola or Mozambique, for example) but that the conception of the proletarian dictatorship itself is wrong. The proletarian dictatorship, at least as conceived by Marx and Lenin, basically assumes the possession of power by the proletariat itself, its organization and self-administration in the concrete and the prevalence of broad democracy for the workers and broad masses. The suppression of the bourgeoisie is linked to this basic conception and thus contradicts any premise which bases itself on the use of power in the name of the proletariat and against the proletariat by a party or any other body. If the pro-Moscow African regimes make repeated reference to the Soviet experience, especially during the Stalin period, the critical evaluation of this experience itself lays bare the weakness of the arguments. The fact is that the particular features of Bolshevism in practice and especially the limitations and aberrations imposed, and adopted as temporary measures, during the period of the Civil War and War Communism, cannot be equated with the basic tenets of socialism even if these were affirmed as dogma in the 1930s. The issue raises the problematic of the role and nature of the proletarian party, but identification of proletarian dictatorship with the exclusion of the workers from the exercise of power and the impositions of restrictions on the democratic rights of the masses cannot trace its rationale/justification to Marxism or socialism.

The struggle for democracy in Africa gives politics its rightful place of dominance over mere economics, it asserts that there can be no deliverance from the grip of underdevelopment unless political power is captured by the masses and an economic endeavor that claims as its purpose their emancipation is undertaken. Official socialism, of all varieties, upheld by the regimes in Africa does not take such emancipation as its motive force: democracy is thus considered as an “obstacle” on the path of economic development. If Kaunda says that the “whole idea of opposition is alien to Africans” he reflects more the desire of the African ruling classes to stamp out all opposition as “un-African.” The idolization of a president as a “father figure” or the substitution of an omnipotent and unique “Vanguard party” for the oppressed masses is all directed at strengthening the authoritarian rule of the classes in power and the perpetuation of the subordination of the people to the State. Therefore, the struggle for democracy in Africa embodies a rejection of the paternalist and elitist conception and affirms the right of the masses to appropriate power and to govern themselves, to organize themselves, etc….

In this respect, then, the struggle for democracy in Africa is not an elitist struggle, as some so-called “Africanists” from the metropoles seem to suggest. For example, a certain Marina Ottoway writing about the Ethiopian Revolution declares that workers in countries like Ethiopia (“with dual economy”) are members of the “modern system and as such a very privileged group”; she bases herself on this argument to label the Ethiopian workers’ demand for democracy as “elitist demands.” Another writer, Santarelli, argues in the same vein and characterizes the EPRP as “westernized” and “representative of the intelligentsia emanating from the most privileged classes.” Such arguments, and to some extent the extended “labor aristocracy” analysis of Arrighi, lead up to or are directed at favorably counter-posing the ruling juntas — “representative of the rural population”! — to the “privileged” urban masses: workers and intellectuals. Behind the seemingly-populist arguments of this genre, it is possible to discern a basically distorted premise: the rural population and way life, at least till the colonial period, represent the “ideal” while the urban masses and way of life, “connected with imperialism,” represent what should be extirpated. Consequently, anti-worker and anti-intellectual juntas are generously called “progressive” and the “representatives of the rural people” by such writers. Connected with this is the recurring theme which asserts that the “bread question” (economic development) is more important than the “freedom question” (democratic rights).

The arguments, which in some cases demonstrate prejudices outside the scope of theoretical/empirical analysis, are fallacious. Colonialism did not bring bourgeois democracy to Africa but neither did it put end to an African “Golden Age of democracy and classless society.” Nyerere’s argument about the existence of a communal classless and idyllic African traditional society is very well known but it is known for its baselessness. A correct presentation of the question indicates that Africa’s problem does not lie in the existence of what some call “the modern system” but rather then in the limitation of “the modern system,” the preponderance of an isolated rural populace, and, above all, the existence of a system of exploitation and oppression which subjugates the masses. The exaltation of the rural areas or the peasantry can satisfy the populist and complexridden conscience of western writers but cannot respond to the exigencies of Africa for coming out of the system of oppression. The democratic forces in Africa approach the question of imperialism not by counter-posing it with some idyllic and illusory rendition of a classless traditional society but by attacking imperialism’s domination and exploitation. The spread of factories and industries, the breakup of the rural state of isolation, etc. … are not by themselves reactionary; in fact, the break-up of feudal relations and ideology and its replacement by bourgeois ones is an advance when evaluated per se. Thus, to label the forces struggling for democratic rights in Africa as “western” and “elites” while exalting repressive and retrograde juntas (such as the one in Ethiopia) and leaders (Amin and Bokassa not excepted) as the “true representatives of Africa’s majority” or as the “mirrors of the souls of Africa untouched by the west” is to manifest crass ignorance and prejudices.

Socialism is a step towards complete human emancipation which will be realized, in the words of Marx, “when the real individual man has absorbed in himself the abstract citizen, when as an individual man, in his everyday life, in his work, and in his relationships, he has become a social being and when he has recognized and organized his own powers as social powers, and consequently no longer separates this social power from himself as political power.” The existence of “bourgeois right” (to each according to his labor rather than according to his needs) under socialism does indicate that actual inequality persists and that the stage is but the first phase of communism. But the criterion for evaluating the level of development of socialism is none other than the level of development of democracy. The more power the masses have and the more extensive their self-administration, the more it can be said that the level of development of democracy is higher, and so also the progress in the transition from socialism to communism. In a country where power is monopolized by a bureaucratic elite, where centralism stands against the self-administration of the masses, where the State/party apparatus converge to marginalize or eliminate the rights of the workers and the masses in the field of organization and administration, etc., in other words where political power is separated from the masses and where this separation continues to deepen, what is in place is not socialism. Socialism is not identified by the existence of a ruling party claiming adherence to Marxism-Leninism, it is not derived from external alliances, or as a consequence of nationalization measures or adoption of the Plan in the economic sphere. The political transition period in which the dictatorship of the proletariat is deemed necessary is also a period which should realize the development of the level of democracy existing in the society, the use of the state in suppressing the bourgeoisie or defending the proletarian power cannot be extended to the suppression of the masses and their exclusion from power. The self-administration of the masses and the free expression of this at the organizational level must be extended, the masses as the holders of power, armed and organized, must be the main defenders of their own power from bourgeois assaults.

The struggle for democracy in Africa justified itself not merely by a general reference to the tenets and ideals of socialism even though this by itself is a heavy indictment against the antidemocratic regimes in the continent who claim to be “socialist.” There is also the question of practical experience, of historical lessons. The experience of the USSR and its satellites as well as that of African “socialist” regimes show that without democracy, without power fully evolving into the hands of the masses, it is not possible to realize even mere economic ambitions let alone socialism. If socialism or the transition towards it is to have any meaning in Africa it must be posed in such terms with firm emphasis on the question of power and democracy. The revolutionary forces presently struggling in Africa must, thus, address themselves to the question in a Marxist manner. The struggle for democracy is not an end in itself and is truly subservient to the struggle for socialism but the latter cannot be realized without political democracy for the masses. This is made especially clear in the countries like Ethiopia where regimes allied to the USSR and following in its repressive conceptions are ruling. As Marx said, “freedom consists in transforming the State from an organ dominating society into one completely subordinate to it, and even at the present time the forms of State are more free or less free to the extent that they restrict the ‘freedom of the State.’”

What Lenin called a truism, the fact that bourgeois democracy is progressive as compared to medievalism, cannot be termed as such in many places in Africa. Distortion of the nature of pre-colonial societies, illusory attempts to “return to the source” and popular mystification by so-called “Africanists” have militated against a correct appraisal of the whole question. If we insist that bourgeois-democratic freedom can assist the struggle for socialism, it implies no “liberal twaddle to fool the workers” or to present this as the aim of the struggle. Our emphasis is that “the proletariat and the revolutionary forces must unfailingly utilize it in the struggle against the bourgeoisie.” At the same time, it falls on the revolutionary forces themselves to evaluate the concrete situation so as to avoid tactical and strategic blunders. By firmly struggling for democracy and by linking this to the struggle for socialism, it is possible to assert the proletariat’s dominant role as the fervent and vanguard fighter of the rights of the masses. Any advance made or victory gained in the democratic struggle will be advantageous for the socialist struggle.

If so-called “Africanists” inclined towards apologetic positions vis a vis existing regimes tend to negate the importance of democracy and to champion “firm rule,” “discipline” and “an all-out drive to combat economic backwardness,” there are also others of the same brand who hail to the sky every national liberation movement or organization which claims to be waging armed or political struggle against the existing regimes. The movements are labelled “revolutionary,” “democratic” and their radical rhetoric is identified with a commitment to socialism. In this way, another mystification and distortion is let loose. A closer observation indicates, however, a different reality.

To be sure, the struggle waged against national oppression has a democratic content in so far as it is directed at the practice of national domination and affirms the right to self-determination of the people. Struggles waged by movements with mere bourgeois-democratic demands have also their progressive content in so far as they stand against absolutist rule and authoritarian domination. However, these struggles are fundamentally different from the struggle for socialism waged by revolutionary forces for whom the struggle for democracy is directed not only at overcoming the limitations imposed on democracy by the bourgeoisie but also for realizing the transition towards socialism and communism, i.e. towards the withering away of democracy itself. Aside from this fundamental difference, there is also the question of the actual feature of the so-called national liberation movements themselves. If these movements in the objective and limited sense assume a progressive function, it is also to be borne in mind that they present no socialist alternative in the concrete. Their method of work, of organization, their relations with the masses, and their conception of the future organization of the society manifest no substantial difference from that of the regimes they are combatting. Thus, underneath their radical rhetorics, in some cases itself an eclectic mixture of nationalism and socialism, and the catchword of anti-imperialism, there stands a basically elitist, anti-democratic, and authoritarian position. The leadership of these movements is in most cases in the hands of the petty-bourgeoisie, populist, and radical in words but repressive and hegemonist once it appropriates power.

The struggle for democracy in Africa manifests, therefore, various features. The one upholding the perspectives of the proletariat is radically different from the others; the latter cannot be called socialist and fall within the framework of the system of exploitation and domination itself. The African petty bourgeoisie, in general, be it as the leader of nationalist movements or declared “democratic organizations,” cannot break out of the limitations of the bourgeois conceptions of society. By coming to power, it can and does reorganize the society in accord with interests; however, its general weakness and class optics account for extremely repressive actions once it comes to power. Contrary to this, the revolutionary forces struggle for democracy having in mind an objective that will asset the workers and masses as the rulers of society. For such forces, the question of the struggle is not “to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another” but to smash the whole state apparatus and set-up new, fundamentally different institutions which reflect and make possible the self-government of the masses and their rising to the level “of taking an independent part not only in voting and elections, but also in the everyday administration of affairs.” For, as Lenin added, “under socialism all will govern in turn and will soon become accustomed to no one governing.”

The struggle for democracy waged to realize this objective needs no other raison d’etre; its commitment to the emancipation of the people from domination and subjugation is its primary and strongest rationale. This commitment and this aspiration overcomes all artificial barriers, be they continental, racial or economic, and it is thus that the struggle for democracy in Africa assumes its importance and forms an integral part of the world-wide struggle for socialism, for communism.