For this episode, Parker and Donald welcome Cosmonaut editor and writer Medway Baker on to Canadasplain the Westminster system. Join us as we put on our inner socdem wonk to discover what went wrong for the Labour Party in the recent UK election.

Reviewing the debates over electoral strategy at the Second Congress of the Comintern, Donald Parkinson reviews the strategies of the Bulgarian Communist Party and their arguments against electoral abstentionism.

The early Bulgarian Communist party is often forgotten, with little in the way of historiography. This is shocking considering that it was one of the only Comintern parties that could say it had a majority of working-class support and control over the union movement.1 It was founded from the left-wing of a Social-Democratic movement that was far more radical than the rest of the Second International. The Bulgarian Social-Democratic Workers Party opposed World War I and supported the Bolshevik revolution. Their most Marxist faction would split from the reformists and form their own party, mirroring the Bolsheviks’ split from the Mensheviks. Yet the Bulgarian Party did not take up the ultra-left position of abstention from elections; instead, they brilliantly combined electoral tactics and revolutionary strategy without sacrificing militancy or giving into a “law and order” perspective of constitutional loyalty. A popular argument today is that participation in elections inherently leads a party toward reformist politics. Yet the experience of the Bulgarian Communist Party stands in contradiction to this claim. This reason alone calls for more attention to the early Bulgarian Communist movement.

Despite being essentially destroyed by a fascist coup in 1923 and only reemerging in the resistance to fascism during World War II, one can gather quite a bit of information on the party’s early years and mass success from the proceedings of the Second Congress of the Comintern, particularly where there is a sharp debate on electoral strategy.2 In this debate, the representative of the Bulgarian Communist Party, Nikolai Shablin, answers to the minority thesis presented by Bordiga against the notion of participation in parliament being mandatory for Comintern parties. This congress established the ‘21 conditions’ for membership in the Comintern, so the debate on the role of elections was intensified. The Bulgarian party played a key role in defending the Comintern majority theses put together by Bukharin, which called for participation in elections to agitate for revolution, a strategy of revolutionary parliamentarism.

The minority theses put together by Bordiga for electoral abstention, or boycott, made a historicist argument about elections once being useful but now being outdated, based on the historical possibility of an imminent revolution. Bordiga concedes that “participation in elections and in parliamentary activity at a time when the thought of the conquest of power by the proletariat was still far distant and when there was not yet any question of direct preparations for the revolution and of the realization of the dictatorship of the proletariat could offer great possibilities for propaganda, agitation and criticism,” but then goes on to argue that because the proletariat was now in a period of revolution, such tactics are a distraction from the central task of taking power (which cannot be done through parliament).3 From this, it followed that parliament should be abstained from. Essentially, the argument Bordiga presented is that electoral participation was historically useful to build up the forces of the proletariat in a non-revolutionary period but in a revolutionary period the aim was to discredit bourgeois democracy, which could only be seen as hypocritical if Communists didn’t boycott parliament. Bordiga added that:

Under these historical conditions, under which the revolutionary conquest of power by the proletariat has become the main problem of the movement, every political activity of the Party must be dedicated to this goal. It is necessary to break with the bourgeois lie once and for all, with the lie that tries to make people believe that every clash of the hostile parties, every struggle for the conquest of power, must be played out in the framework of the democratic mechanism, in election campaigns and parliamentary debates. It will not be possible to achieve this goal without renouncing completely the traditional method of calling on workers to participate in the elections, where they work side by side with the bourgeois class, without putting an end to the spectacle of the delegates of the proletariat appearing on the same parliamentary ground as its exploiters.4

This rejection of electoral tactics based on a broad historical abstraction such as “the era of revolutions” is contrary to the dynamic revolutionary strategy of Lenin, who correctly argued against such notions exemplified by Bordiga’s arguments in his Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder. Historically, on a grand scale, the era may have been one of revolution, but bourgeois parliaments were not discredited in the eyes of the proletariat, as reformists still maintained leadership of the labor movement. Thus the reformists had to be actively discredited through political struggle, not through empty measures such as boycotts but by directly agitating and fighting for communist politics in the halls of parliament. This also meant connecting parliamentary struggles with struggles outside parliament in factories and working-class communities. The delegitimation of bourgeois parliaments would be accomplished through active political struggle, not simply declaring the nature of the historical epoch.

Another protest against electoral participation was given by a delegate from England, William Gallacher, who represented the Shop Stewards Movement. Gallacher would go as far to say that the Third International was opportunist for participating in elections and took a position further to the left than Bordiga, who still accepted the 21 Conditions of the Comintern despite his disagreements. While lacking the grand historical pronouncements of Bordiga’s arguments, Gallacher’s argument is essentially the same in its tactical conclusion: that electoral work is a distraction from more important work, that energy put into elections in any form offers few returns for its efforts and risks, and that this energy could instead be put into something that will truly challenge the state or more directly organize the working class. He argues that one who enters parliament can “…make speeches there and thus agitate. The result is, however, that the proletariat becomes accustomed to believing in the democratic institutions.” In the end, the argument is that of “democratic mystification”, that by voting in bourgeois elections and supporting workers’ candidates the worker puts faith in bourgeois institutions and is “softened” by the system, compelling them to refrain from radical action. This argument is similar to Georges Sorel’s critiques of electoral socialism and embrace of vitalist syndicalism, which undoubtedly captured a certain class impulse but was an openly anti-scientific and irrationalist theory that relied on a notion of myth to hold itself together. Either way these anti-electoral arguments found popularity in the Comintern due to the prominence of syndicalists entering the movement, with backgrounds similar to Gallacher’s, aiming to push the Comintern into making immediate war on capitalism.5

Shablin answered Bordiga and Gallacher’s critiques in an excellent polemic that offers insight into the tactics of the early Bulgarian Communists and their effective merging of “the ballot and the bullet”. Shablin immediately attacks Bordiga’s detached historicist theorizing with recognition of concrete political reality:

“Even if the Theses Comrade Bordiga proposes to us proclaim a Marxist phraseology, it must be said that they have nothing in common with the really Marxist idea according to which the Communist Party must use every opportunity offered us by the bourgeoisie to come into contact with the oppressed masses and to help communist ideas to be victorious among them.” 6

Shablin recognizes that the conditions of revolutions are not simply created by epochs of history but by the strength of the proletariat organized as a political force. To accomplish this, Communists must fight for political hegemony in all spheres of civil society and actually win the masses to their politics. The electoral sphere is one of the most publicly visible and dominant spheres in civil society underdeveloped capitalism and therefore cannot be left purely to reactionaries and reformists. For Shablin, Bordiga’s theses represent the remnants of an antiquated, economist, and anti-political tendency in the labor movement that must be overcome. This tendency came from syndicalism—an anarchist school of the workers’ movement that the Comintern aimed to win support from. A challenge for the Comintern was not just overcoming the limits of Social-Democracy but also the anarchism and political indifference of syndicalism which also dominated the pre-war workers’ movement.

In his rebuke to the promoters of electoral abstention, Shablin highlights the history of Bulgarian Social-Democracy. Both Bulgarian Social-Democracy and the Bolsheviks shared a record of intra-party factional struggle in which revolutionaries and revisionists, unable to reconcile, separated into distinct organizations. The starkest divide was developed between reformists who hoped to appeal to “all productive strata” (meaning a class alliance with the petty-bourgeois), and Orthodox Marxists aiming to build a class independent party. This divide led to the party split in 1903, with the “narrow socialists” vs the “broad socialists” representing the revolutionary wing and the reformist wing of the Bulgarian labor movement. The “narrow socialists” captured most of the local leadership and would go on to become the Communist Party. Unlike other sections of the Second International they opposed World War I. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia granted them the honor of being the pre-October Revolution faction of Social-Democracy closest to Bolshevism.7 For example, their opposition to imperialism was matched only by Lenin in the Zimmerwald Left, boycotting the Stockholm Conference in 1917 because it didn’t call for peace without annexations.8 This similarity with the Bolsheviks can be seen in their mixture of revolutionary intransigence and uncompromising anti-imperialism with tactical flexibility. Yet the Bulgarian party themselves were unaware of the Bolshevik/Menshevik conflict, taking more influence from the German party.9

Having split from the right wing, the left Social-Democrats of Bulgaria were able to mount an opposition to imperialism. Against the notion that the rise of imperialism and revolutionary circumstances make electoral tactics obsolete, Shablin explained how the Bulgarian Revolutionary Social-Democrats used parliament to fight against war, citing their reaction to the Balkan wars of 1912-13 and WWI:

The Bulgarian Communist Party fought energetically against the Balkan War of 1912-13, and, when this war ended with a defeat and a deep-going economic crisis for the country, the influence of the Party in the masses had grown so far that in the elections for the legislative bodies in 1914 it won 45,000 votes and 11 seats in parliament on the basis of a strictly principled agitation. The parliamentary group protested violently on several occasions against the decision of the Bulgarian government to participate in the European war and voted each time demonstratively against war loans. With the help of pamphlets and illegal leaflets, through zealous agitation and propaganda, the Party carried out a violent struggle against the imperialist war once it had been declared, not only inside the country but also at the front.10

This strategy, though bringing about a great amount of oppression from the bourgeoisie, was essentially the opposite strategy of the majority of the Second International during WWI. It combined both the ballot and mass action in a revolutionary way, and despite the repression that followed this brave anti-imperialist strategy, when the CP formed and entered elections in 1919 it was resoundingly successful:

This bitter struggle against the war, the complete bankruptcy of the bourgeoisie’s policy of conquest and the serious crisis caused by the war gave the Communist Party the opportunity to extend its field of work and its influence among the masses and to become the strongest political party in our country. In the parliamentary elections of 1919 the Communist Party received 120,000 votes and entered parliament with 47 Communist deputies. The social-patriots, the ‘socialists’, could only muster 34 representatives, although the Ministry of the Interior was in the hands of one of the leaders of this party, in the hands of the Bulgarian Noske of sad memory, Pastuchov.11

This was irrefutable proof that electoral struggle could indeed be used to further a revolutionary agenda, especially if a party is strong in its principles and has a real base among the working class. It also showed that by taking a strong anti-war stance, the Communists could gain credibility with the masses rather than conceding to chauvinism as their opponents to the right did. For the Bulgarian CP, electoral work and “mass action” were not counterposed but fed into each other. The party organized mass strikes and demonstrations, inspired by the Russian Revolution to increase the militancy of tactics. Yet this was not the end of electoral success for the Bulgarians. In 1920 their number of deputies rose to 50 even after parliament was dissolved and reformed by the government, while the reformists dropped down to 9 deputies.

This mere electoral success terrified the bourgeois into more white terror but also showed that through electoral contestations that Communists could weaken the right wing of the labor movement that held back revolution. Communists in 1920 held a majority in parliament, so the bourgeois reacted by ejecting CP deputies. The bourgeoisie had to abandon any formality of democracy to maintain its class dictatorship in face of a parliament subverted by communists that held the backing of the masses. Shablin summarized the general strategy of the party as follows:

The Communist Party is carrying out an unrelenting struggle in parliament against the left as against the right bourgeois parties. It subjects all the government’s draft laws to strict criticism and uses every opportunity to develop its principled standpoint and its slogans. In this way the Communist Party exploits the parliamentary rostrum in order to develop its agitation on the broadest basis among the masses. It shows the toilers the necessity of fighting for workers’ and peasants’ soviets, destroys the authority of and belief in the importance of parliament, and calls on the masses to put the dictatorship of the proletariat in the place of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.12

Against claims that participation in parliament would retain the stability of bourgeois democracy, the insurgent electoral strategy of the Bulgarian socialists and communists instead showed that through vigilant agitation in the halls of bourgeois power backed by a real mass movement, electoral action would break down the facade of bourgeois democracy by seeing the state resort to more dictatorial methods and creates “states of exception” in response to gains made by the working class through mechanisms of bourgeois democracy. As the Bulgarian CP “threw a wrench” into the normal “democratic” mechanisms for which the ruling class rules through the state, the bourgeois responded with white terror and dismantling of democratic structures themselves. This is what Marx called “the battle for democracy,” where the proletariat shows itself to be the class that represents the true “will of the people” while the bourgeois is revealed as a class of tyranny rather than democracy. The Bulgarian CP fought this battle, but to a degree to where a heavy price in human life was paid due to the repression of the propertied classes against a rising Communist movement.

Against the argument that elections “divert energy” from direct actions or general base-building in proletarian communities, the Bulgarian CP showed how these processes could be synergistic and build each other up, not simply see electoral activities parasitic toward the on-the-ground organization of workers. This synergy is particularly described by Shablin in his speech regarding industrial actions, which at this time were seen as the true focus of organization by the “left” critics of electoral practice in many cases:

“The Bulgarian Communist Party fights simultaneously in parliament and among the masses. The parliamentary group participated in the most energetic way in the great strike of the transport workers, which lasted 53 days from December 1919 until February 1920. For this revolutionary activity the Communist deputies were robbed of their legal protection by the government, and several deputies were arrested. Comrades Stefan Dimitrov, the representative from Dubnitza, and Temelke Nenkov, the representative from Pernik, were sentenced, the first to 12, the second to 5 years imprisonment, because they had opposed the state power arms in hand. Both comrades are today languishing in jail. A third Communist deputy, Comrade Kesta Ziporanov, is being prosecuted by the military authorities for high treason. The members of the Central Committee, three members of parliament, were prosecuted because in parliament and in the masses they carried out an energetic struggle against the government, which was supporting Russian counter-revolutionaries. They were provisionally released from custody on a bail of 300,000 Leu, which was guaranteed and paid in the course of two days by the proletariat of Sofia. All the Communist members’ speeches in the chamber against the bourgeoisie are of such violence that they frequently end in a great scandal, and the government majority and the Communist group come to blows.”13

These experiences, of course, did not prevent the rise of an anti-electoral faction in the party.

In 1919 a faction arose demanding the boycott of parliament, perhaps in reaction to the repression of Communists deputies. This was a weak faction in the words of Shablin, and was unanimously rejected when it came to a vote at the party congress. Rather seeing soviets and participating in bourgeois elections as counterposed, the Communist Party of Bulgaria worked to form soviets while running in elections at all levels of government. This was similar to the tactics of the Bolshevik party in the days leading up to October, where the Bolshevik party worked to win a majority within the Soviets around the program while also running in bourgeois elections at all possible levels. This created a synergy between the campaigns of the party to form Soviets and electoral campaigns:

So far, in the councils in which it has possessed a majority, the Communist Party has fought for their autonomy; it calls on the workers and poorer peasants to support by mass action the budgets adopted by the Communist councils, by which the bourgeoisie is to be burdened with a progressive tax, which can be extended as far as the confiscation of their capital, and frees the working class from all taxes. Big sums can then be spent for public works, elementary schools, and other purposes that serve the interests solely of the working class and the poor, and the special interests of the minority of the bourgeoisie and of the capitalists go completely unheeded.14

This relationship saw the existence of Communists in the mass organizations of the proletariat that were counterposed to the bourgeois state as well as within the bourgeois state not contradictory but rather complementary. Winning majorities in the Soviets and demanding their authority be recognized from within the government saw a way to combine the actions of the proletariat “from below” with an electoral strategy that was “from above”, to use a flawed metaphor that is nonetheless common in the left. For the Bulgarian CP, the question of power was not the ballot box or insurrection, but rather a political struggle that combined the two as necessary. When describing the workers’ soviets of Bulgaria and their relation to the communist deputies, Shablin argues that the working class struggle to defend their gains or ‘communes’ is an educational process that will train the working class to take power. It is clear, given the level of state repression Shablin describes, that he sees the necessity and importance of working-class self-defense.

In the next session on parliamentary strategy, Shablin continued to defend his position, this time the Swiss delegate Jakob Herzog joined in to represent the “minority” anti-electoral position. Herzog begins his argument by saying that participation in democratic institutions, by giving workers an ability to increase their standard of living, deadens the revolutionary spirit of the workers is the general cause for a pro-electoral communist trend. Russia is seen as capable of revolution not because of the Bolsheviks ability to agitate legally and illegally but because of the primitive nature of its democratic institutions, making the workers more desperate to revolt. This kind of muddled, catastrophist and economist thinking shows the level of theoretical sophistication that arguments against electoral participation had in the Comintern. Herzog then goes on to mock the Communist Party of Bulgaria itself and the idea it is a “model of revolutionary parliamentarism”, saying that he knows someone who saw the Bulgarian party itself and became anti-parliamentarian because of their disappointment.15 Shablin accuses Herzog of slander, saying that parties activities are well publicized and known to all.16 Either way, even if Herzog’s story is the truth, it is not an actual indictment of electoral tactics or the CP of Bulgaria, but simply the reflection of an individual. Herzog’s argument doesn’t carry the day regardless, with Bukharin successfully defeating the minority thesis proposed by Bordiga. The verdict of history on anti-electoral communism isn’t necessarily out yet either, but so far its track record in building long-lasting institutions of the working class is very poor.

Within the Comintern’s Second Congress, the Bulgarian CP defended a line on electoral strategy close to that of the original pre-revolution Bolshevik party, while other parties argued for, essentially, syndicalist influenced notions of a party that would only put its energy into direct opposition to capitalism, the party essentially being a battalion of workers ready to go to war with capitalism. This was certainly how Bordiga saw the Italian CP when under his leadership: an organization formed during a period of international revolution to wage war on the bourgeois state. Yet this vision of the party was not able to win over the masses and can be seen as being at the root of much that was flawed with the Comintern. The notion of impending revolution may have made sense given the level of global catastrophe and class struggle, but a fatalistic understanding of this world revolution as an inevitable event that the party simply had to line up for led to a sort of strategic sterility in many of the Comintern parties, especially earlier on. What was lacking was a long term strategy for revolution, which saw revolution not as something that would outburst at any moment, triggering the mass strikes that would lead to a Soviet Republic, but a process of which the party builds up its forces in a protracted process with tactical flexibility but programmatic clarity.

The Bulgarian CP, unlike the Bolshevik party, was not able to use their strategy to come to power. The party, despite its strength in combining electoral tactics with a revolutionary program, also had weaknesses. In 1923 a fascist coup took power in Bulgaria, triggering a spontaneous uprising. The Bulgarian CP refused to join in and take leadership, seeing the conflict as merely a squabble between two bourgeois factions. Yet spontaneous resistance without Communist leadership to fight for the dictatorship of the proletariat cannot defeat fascism. The result was that the uprising was defeated while the CP stood still. This was not an uncommon attitude in the Comintern in response to the rise of fascism, unfortunately, most famously repeated in Italy and Germany. Historian Julius Braunthal compares their attitude to that of the KPD during the Kapp putsch, where the reactionary officer caste attempted a coup and the Communist party stayed neutral to avoid ”defending capitalist democracy.”17 The Comintern Executive, particularly Zinoviev and Radek, was disgusted with this failure to take the lead in resisting the putsch and ordered the Bulgarian party to organize an uprising against the new government. While the leadership of the Party rejected this, the majority voted to follow the Comintern plan and overthrow the government to work towards a Soviet Republic. The result was a fiasco, where only “small isolated groups of Communist party members did take up arms, but only in scattered villages”.18 Zinoviev and Radek, on the other hand, had hoped the uprising would trigger a revolution in Romania and Yugoslavia, but they were blind to the actual on the ground situation in Bulgaria. Who was to blame? Was it the Comintern Executive for forcing an uprising on the party that it wasn’t prepared for, or the leadership of the Bulgarian CP for not supporting the initial mass uprising against fascism? Either way, such mistakes cannot be repeated, and mechanical uprisings engineered from abroad are unlikely to be a means success, as is refusing to take leadership in mass struggles against fascism. As for Comrade Shablin, he was murdered in 1925 by the Bulgarian police.

While the experience of the Bulgarian CP can show the use of electoral tactics, it also shows the limitations of a purely electoral approach. This is not to say the Bulgarian CP had such an approach, but rather that their success was due to the aforementioned “synergy” between electoral and mass action as well as their willingness to engage militant self-defense against the violence that the bourgeois will unleash on any attempt to throw them out of power, even if these attempts are made through legal democratic means. The Bulgarian CP faced an immense amount of repression and was only able to survive as an organization by going into illegality after 1923.

The insurgent electoral strategy of the Bulgarian CP and its predecessor Social-Democrats is far removed from the tepid reformism of much of the left, who promote an electoral strategy that tails the “left wing of the possible” and aims to compromise in every possible way, from the general notion that it is impossible to even work outside the democratic party with excuses being made for every capitulation made by a self-described social-democrats capitulation to the right. Yet on the other hand, due to the prominence of a reformist rather than insurgent electoral strategy, electoral tactics are dismissed altogether which sees the abandonment of a key weapon in the historical class struggle out of fear that such tactics can only lead to reformism. The experiences of the early Bulgarian Communist party during this period shows how electoral tactics can be a powerful tactic in the class struggle and help de-legitimate rather than legitimate the bourgeois system. The choice is not between voting and revolution, as some Maoists and anarchists like to put it. Rather, the choice is between engaging in all spheres of civil society possible where we can fight for our politics or simply leaving them as theatres for the bourgeois and their allies.

The United States is a mockery of what democracy is supposed to be. J.R. Murray unpacks the reality of a corrupt system that is designed to empower the rich against the working class majority.

In the eyes of global elites and much of the populations they govern, liberal democracy’s defeat of Fascism and Communism in the 20th century has left it the only viable political system. Many now assume Liberal Democracy sits among humanity’s crowning achievements – with no greater advocate than the United States. But for all the mythology around the concept, 21st century liberal democracy suffers from a crisis of legitimacy. Right-wing populism and its violence exercise power in a growing number of countries with the intention of preventing select populations from taking part in democratic processes. Simultaneously, Marxism, considered defeated and marginal, is seeing a modest resurgence.

Meanwhile, the United States, the wealthiest and most powerful liberal democracy in the world, experiences outrageously high inequality, stagnant wages, an abysmal healthcare system, a housing crisis, routine acts of police violence, and impending ecological catastrophe. The majority of people in the country are suffering with no end in sight. Shouldn’t a democratic political system address those problems? If so, then why are they only getting worse?

The fact is that the capitalist class erects such enormous obstacles to actual democracy that most people can’t or won’t participate in the token democratic processes that do exist. Liberal democracy is, as Lenin once said, “democracy for an insignificant minority, democracy for the rich.”

This is an overview of anti-democratic characteristics and institutions of the U.S. political system, the standard-bearer of democracy for the minority.

The United States, historically and presently, systematically suppresses votes. Black Americans, enslaved until the mid-19th century and then openly terrorized, segregated, and disenfranchised through the 20th and 21st centuries, did not get the vote until the 1960s due to various legal, illegal, and quasi-legal methods. Additionally, (white) women could not vote until 1920, and up to the mid-19th century, voting was commonly restricted based on property. Today, measures which produce voter disenfranchisement are still in place.

To start, election day is not a national holiday, but a regular workday. Working on election day makes it incredibly difficult to find time to vote. Higher income voters may be able to take time off, but the poorest workers cannot, and with polling places closing between 6pm and 8pm, it is impossible for some to get to the voting booth. Liberals accept early voting as an acceptable solution to the problem but some states enacted laws restricting early voting. For many, the chance to vote remains subject to the whim of employers.

But voter suppression goes deeper than simply making it hard for workers to find the time to vote on election day. Conservatives, in a cynical plot to suppress the votes of the poor, spread the myth of widespread voter fraud and use it to enact repressive voter identification laws in many states. Such laws restrict the types of identification polling stations will accept– work, college, and public assistance IDs are among the types not accepted. Those restrictions disproportionately affect minorities, immigrants, and the poor—populations which may not have the money, transportation, or time required to obtain appropriate identification.

Of course, voter ID laws are an obstacle only for registered voters. In some states, like North Carolina or Florida, state officials purge the roles of registered voters under spurious accusations of voter fraud. Up to 51 million eligible voters in the United States aren’t registered to vote, and right-wing lawmakers are attempting to make it more difficult to register. The simple solution is to automatically register everyone to vote, but the political capital to do so is nonexistent.

Only the working class faces myriad obstacles to cast their ballots, and the poorer the worker, the more obstacles appear before them.

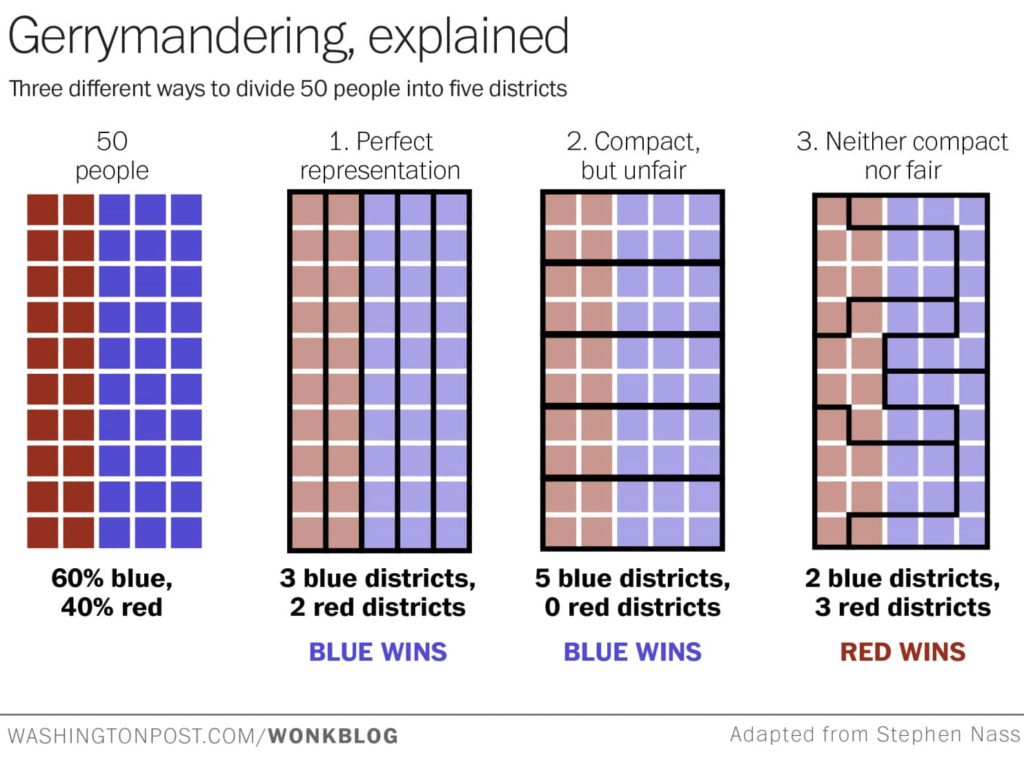

Gerrymandering is essentially the redrawing of voting districts by a political party to gain an electoral advantage. It is a concept easier to understand with a visual (from the Washington Post):

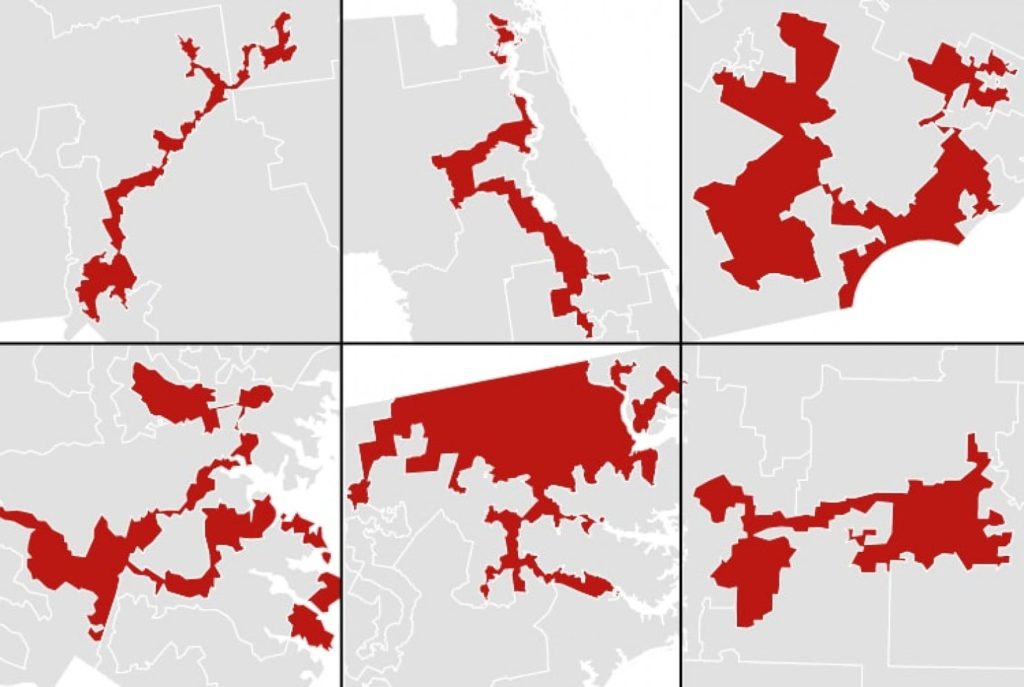

The party in charge of drawing congressional districts can divide the map any way they want, which often means cutting up known progressive population areas into little pieces and then grouping those pieces with larger conservative districts. This essentially dissolves the left-leaning vote. Notice how absurd the shapes of these districts get:

In the 2014 midterm election gerrymandering allowed Republicans to retain control of the House, despite being outvoted. Mother Jones provides a good visualization of the 2014 election here:

In the 2018 midterm elections, Democrats took the House, but by a smaller margin than expected due to gerrymandering. It’s clear that the process is both deeply bureaucratic and anti-democratic, but as long as those who benefit are in charge, it will continue.

Presidential elections are just as bureaucratic and convoluted as legislative ones. On election day it appears that you are casting your vote for president, but really it’s more complicated. While drawing up the Constitution, there was a major disagreement centered on whether to have Congress or all land-owning men elect the president. They compromised by creating the Electoral College.

The Electoral College works like this: before the presidential election, a slate of “electors” are nominated by each political party. When you cast your ballot you are not voting for a candidate, but a political party’s electors. The Electoral College consists of 538 electors, with 270 forming a majority. All but two states have a “winner takes all” system. For example, the state of New Jersey has 14 elector spots to fill or 14 “electoral votes”. If a majority of the population votes for the Democratic Party, then all 14 elector slots go to the Democratic Party electors, who vote for the Democratic candidate at a later date. This occurs in each state until one party has 270 electoral votes. Everyone who voted Republican in New Jersey? Their votes never make it to the Republican candidate. Everyone who voted Democrat in Texas? Their votes are effectively thrown out.

To simplify– each state counts for a certain number of points. NJ 14, Utah 3, California 55, etc. Whichever party gains the most votes in California receives 55 points for their candidate. Your vote does not actually count toward your preferred candidate. Instead, it decides which candidate gets the points your state has to offer. This means that the President of the United States is not chosen by popular vote. This has serious consequences. There are presidents who have lost the popular vote but won the election—most recently, Donald Trump and George W. Bush.

While it’s necessary to examine individual policies that restrict democracy, it’s also important to analyze anti-democratic social and economic structures the policies operate within. A simple explanation of capitalism illuminates and contextualizes these structures.

The world can be divided into two broad groups of people: those who own the things necessary for society to function and for people to survive, and those who do not own these things. The first group, the capitalists, owns everything from factories to transportation infrastructure, farmland to real estate, and everything else used to produce our society. The rest of us—the workers—write the code, drive the trucks, stack the shelves, work the call centres, serve the food, pack the packages, and ensure that the things capitalists own operate correctly. It is not a symbiotic relationship, but an exploitative one. The workers own only their labor power, which they sell to a capitalist in exchange for wages. But wages are always less than the profit that workers produce for the capitalist.

One way that the capitalist class maintains this exploitative system is through the state.

The state’s primary function is as a tool used by one class to suppress another. Under feudalism, it was used to exploit and oppress serfs for the benefit of lords. In modern society, it is used by capitalists to exploit and oppress workers.

We are conscious of this when we speak of “money in politics“. U.S. elections, presidential or otherwise, are primarily funded by wealthy individuals and corporations. “Citizens United”, the Supreme Court decision allowing corporations to funnel a previously unheard of amount of money into political campaigns via “Super PACs,” is the most famous example. But even if Citizens United were repealed the rich would continue to buy our democratic process. Besides individual capitalists bankrolling entire political campaigns, billionaires own the media whose job it is to report on elections, coordinate with and fund influential think-tanks that shape policy, and even draft legislation.

Lobbying by capitalists is particularly detrimental to authentic democracy. Each lobby organizes by industry to convince lawmakers to enact profitable legislation for that industry. Pharmaceutical companies, oil companies, defense manufacturers—every single industry—have powerful lobbyists in Washington. In what amounts to bribery, lobbyists treat members of Congress to expensive dinners, sporting events, and expensive vacations where they plead the case for their industry. During these one-on-one meetings, politicians are often promised jobs as lobbyists if they comply with the industry’s demands. The transition from public servant to private lobbyist comes with a pay raise and mostly consists of calling in favors from old friends and colleagues to influence policy. This “revolving door” permeates through all levels of government from high ranking officials to congressional staffers and bureaucrats.

This “revolving door” is a clever metaphor masking a more insidious truth—capitalists and politicians are identical. Legislators, cabinet members, and administration bureaucrats all slide effortlessly between the role of a public official and companies like Goldman Sachs, ExxonMobile, and Lockheed Martin. This is most explicit in the Trump administration, where former CEO of ExxonMobile ran the State Department, and the Environmental Protection Agency is currently run by a former coal lobbyist. And this is not to mention Trump himself, a billionaire real estate developer.

The interchangeability of capitalists and government officials is not unique to the current government, but a fact of every presidential administration. After his stint in government former Attorney General Eric Holder, who chose not to prosecute any of the big banks after the 2008 financial meltdown, rejoined Covington & Burling, a law firm that represents the largest banks on Wall Street. Holder now works alongside Michael Chertoff, Secretary of Homeland Security from 2005–2009. Chertoff is the co-founder of the “Chertoff Group”, a risk-management and security consulting company that employs former members of the U.S. government including Michael Hayden, former director of the CIA and NSA; a man responsible for Guantanamo Bay, CIA black sites, government surveillance, and countless extrajudicial killings abroad.

The Chertoff Group is far from the only influential business employing former government officials. Lisa Jackson, head of the EPA from 2009-2013 now works for Apple. The former director of the Domestic Policy Council, Melody Barnes, sits on the board of directors for the defense contracting giant Booz Allen Hamilton. Obama’s former Deputy Chief of Staff, Mona Sutphen, went on to work for UBS, a global financial services company. She was also a partner for Macro Advisory Partners, whose purpose—which is clear even when coated in sterile language—is to develop strategies for corporate clients to exploit the global poor. Rich Armitage, Deputy Director of the Bush administration’s State Department, is a board member for ManTech International, a defense and national security company whose other board members include a former CIA official who helped assess intelligence information during the lead up to the Iraq war, the head of an investment management firm, and a retired Lieutenant General. Samuel Bodman, Deputy Secretary of the Department of Commerce from 2001-2004, Deputy Secretary of the Treasury from 2004-2005, and Secretary of Energy from 2005-2009, joined the board of directors for the chemical giant Dupont shortly after leaving the White House.

The list stretches on forever. Every administration official, senator, representative, and congressional staffer comes from or moves onto powerful law firms, lobbying firms, think tanks, NGOs, defense contractors, transnational corporations, or other powerful private institutions.

These are the people socialists refer to as “the ruling class”, and they cannot be voted out of power. If a congressman loses an election he merely becomes a lobbyist and gains even more influence. If the term limit of an administration ends, the individual functionaries and bureaucrats join institutions that hold enormous power over the state. No election can rid the state of capitalist interests; no election can force the state to work in the interest of the working class.

In 1956 W.E.B. Dubois explained his refusal to vote, “I shall not go to the polls. I have not registered. I believe that democracy has so far disappeared in the United States that no ‘two evils’ exist. There is but one evil party with two names, and it will be elected despite all I can do or say”. Dubois’s analysis is still applicable. The Democrats and Republicans are factions of the same party—the capitalist party. The division between the two occurs over a difference in strategy, not a difference in goals.

Each party is ultimately beholden to the special interest groups funding them, all of whom wish to maintain capitalism and ensure their industry benefits from its maintenance. A base of committed voters must be catered to, but only within the boundaries set by elites. If possible, all debate is restricted to “culture war” issues that, while important, are debated in a way that refuses to confront capitalism. Additionally, while it is generally true that people suffer more under Republican administrations, people continue to suffer immensely under Democratic ones. Both parties are culpable in creating the conditions for misogyny, racism, poverty, exploitation, and all the ills of capitalism.

Republicans appeal to the economic interests of small business owners and the most backward elements of the working class to cut social programs and attack minority groups, while the Democrats appeal to urban professionals and progressive sections of the working class, to surreptitiously implement policies with similar consequences. Democrats helped lay the groundwork for the Trump administration’s worst authoritarian excesses. Some examples include mass deportations, expanding the war on terror, prosecuting whistleblowers, expanding mass surveillance, increasing fracking, and regime change.

Despite not being banned outright, third parties face various anti-democratic measures ensuring their defeat at the polls. During a presidential election, the Electoral College represents the most blatant obstacle to democracy. A candidate, third party or otherwise, can gain 49% of the vote in a state and receive no electoral votes. First past the post voting extends downwards to most congressional and state elections, guaranteeing a loss of representation for everyone who did not vote for the winning candidate. Third party candidates often can’t be voted for at all. In the 2016 presidential election cycle, the Libertarian Party was the only alternative party with ballot access in all 50 states. The Green Party gained access in 45. This was possible because they had the money and full-time organizers to petition for ballot access. Explicitly socialist parties do not have the resources to navigate the complexities of gaining access to the ballot.

First past the post voting and ballot access aside, it is still an uphill battle for alternative political parties. Campaign funding reimbursement is only available to parties who receive 5% of the popular vote during federal elections. Any prospect of obtaining it is hindered by poor media coverage and the 15% poll requirement to gain entry into national debates, which are run by an organization completely dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties.

Every U.S. civics textbook explains that the government is built upon a series of “checks and balances”. The Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches of government balance power between themselves and check the power of any branch hoping to gain an advantage over the other two. It is said that these checks and balances are necessary to sustain democracy, and yet, as we have seen, we live in a deeply undemocratic society. The reality is that each branch of government is itself undemocratic, and the most democratic of the three, the legislature, has the most checks restraining it.

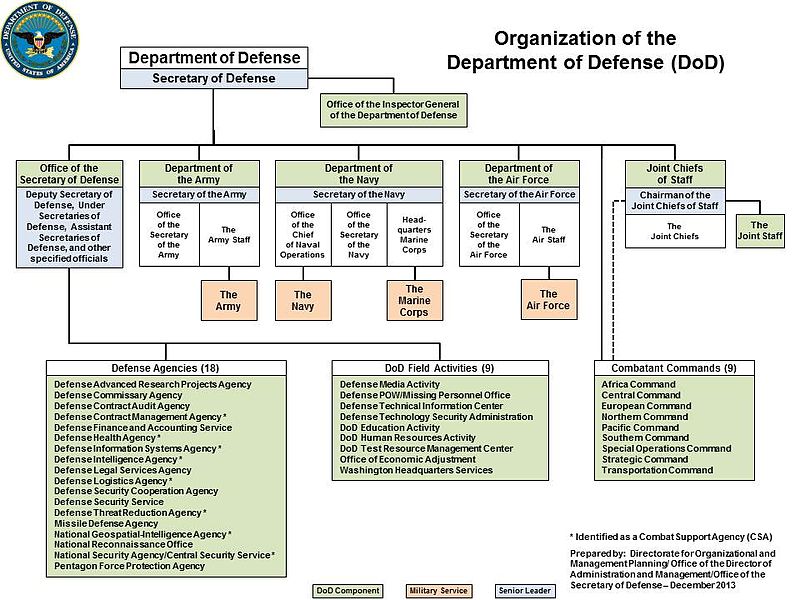

The Executive branch is a sprawling bureaucracy (headed by a president selected through an undemocratic election process) that gains more power every decade. Each department of the executive branch unfolds into a vast bureaucracy of unaccountable functionaries. The Department of Defense alone encompasses the office of Secretary of Defense, Defense Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, National Reconnaissance Office, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Department of the Navy, Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, and accounts for 21% of the federal budget. On election day voters elect one candidate, and that one candidate appoints and oversees this military bureaucracy.

The Executive controls almost all aspects of foreign policy with this endless bureaucracy. The Executive’s power in this regard is made clear by the numerous “conflicts” it has initiated over the heads of Congress since the invasion of Vietnam. Congress, allegedly vested with the sole power to declare war, hasn’t done so since World War Two. Under Obama, the executive branch improved and formalized its ability to kill anyone around the world at will. Congress was unable to prevent the Trump Administration from tearing up the Iran Nuclear Deal. Now the administration threatens to take military action, likely without approval from Congress. There are no checks or balances on the United States war machine.

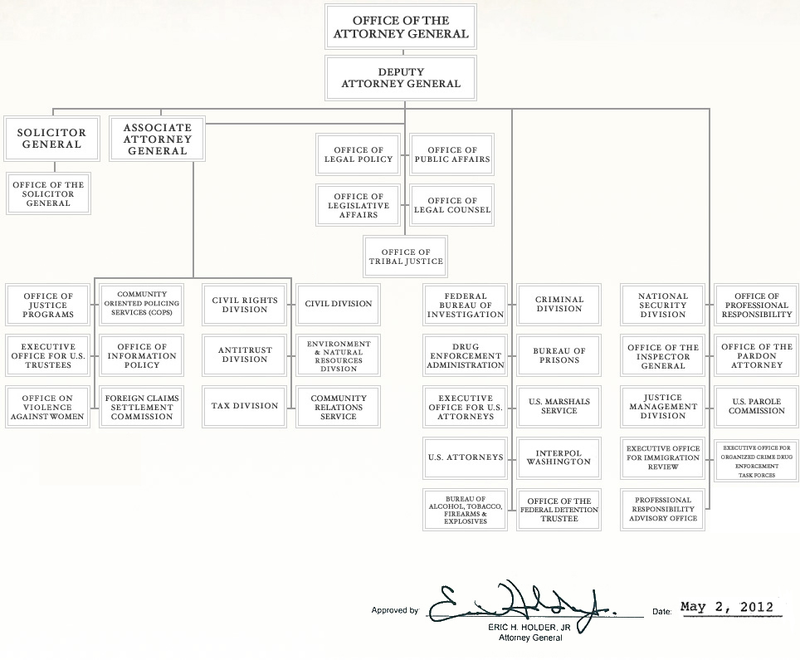

Of course, this is simply one section of the sprawling Executive branch. Every section of the branch is similarly large and complex. Here is the Department of Justice:

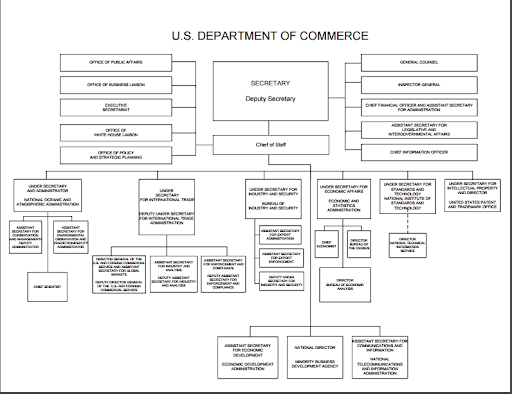

And this is the Department of Commerce:

These bureaucrats are far removed from any democratic accountability, and as we have seen, often use their positions to make themselves rich and advance the interests of their capitalist friends. Bureaucracy is not inherently undemocratic, and when managing a country of 350 million people some form of it is necessary, but minor checks on Executive bureaucracy do nothing to hold it accountable to voters.

Additionally, the President appoints unelected “czars” to coordinate between different departments. In this way, the Executive unifies its bureaucracy around different issues in an attempt to bypass Congress. Writing for Dissent magazine, Mark Tushnet explains,

Presidents appoint czars to deal with new policy problems that cut across regulatory areas, like managing the recent automobile bailout. In a different political environment, presidents might send legislation to Congress. Believing that to be pointless, however, most presidents have decided to appoint czars to pull together everyone who has existing statutory authority in a particular field of policymaking. The czars have no power to develop new regulations, but their prominence and White House credentials give them enormous influence over those who do the regulatory work—and this helps enact presidential policies without congressional oversight.

Ostensibly, it is the purpose of the Legislative and Judicial branches to hold this vast, powerful, bureaucracy accountable, but the Executive has checks on these branches too. Popular legislation passed by Congress can be vetoed by the president, ending the democratic process with a single signature. Additionally, the president nominates which judges sit on the Supreme Court, and no president will nominate a judge keen on limiting executive power.

However, Executive checks on the Legislative and Judicial branches are not the root cause of their ineffectiveness. The two branches are internally dysfunctional and authoritarian on their own.

The Legislative branch is the most democratic of the three branches. Unfortunately, this means very little. The Executive branch constantly bypasses Congress, which is evident in the creation of policy czars, the top-down bureaucracy, and the “deep state” that it represents. It is further compromised by the two-party system and the revolving door and is subject to the same voting restrictions and voter suppression detailed above.

Beyond these limits and restrictions, the Legislative branch resists popular demands all on its own. Much of the blame for this falls at the feet of the Senate, the most reactionary, undemocratic, elitist institution of any modern liberal democracy. Its existence is predicated entirely on suppressing the more democratic House of Representatives.

The Senate does not abide by the democratic principle of “one person, one vote”. Instead, it practices “one state, one vote”. While states send representatives to the House proportionate to their population, the Senate is selected on the premise of equal representation of all states. Wyoming, population 584,000, has the same number of votes in the Senate as New York’s almost 20 million people. This is how Senators representing a small minority of the country block the will of the majority. The anti-democratic mechanisms are so blatant that a political party receiving more votes than its opponent won’t necessarily gain more Senate seats. Senators representing sparsely populated states effectively hold democracy hostage not only through voting down popular legislation but also through filibustering, which allows 41 Senators representing less than 11% of the population to block legislation from being voted on at all. Any legislation passed by the House can be rejected or altered by the Senate. It has veto powers over executive appointments and treaties. Two-thirds of the Senate is required to pass a constitutional amendment.

The Senate is a powerful minority ruled institution, with members bankrolled by capitalists, acting as a bulwark against popular progressive legislation. As such, it plays an important part in the Right’s domination of American politics. Daniel Lazare, writing for Jacobin, explains:

Over the next decade or so, the white portion of the ten largest states is projected to continue ticking downward, while the opposite will occur in the ten smallest. By 2030, the population ratio between the largest and smallest state is estimated to increase from sixty-five to one to nearly eighty-nine to one. The Senate will be more racist as a consequence, more unrepresentative, and more of a plaything in the hands of the militant right.

As time goes on the Senate will become more dominated by populist white nationalists at the expense of popular working class demands.

The Supreme Court is the final interpreter of the U.S. Constitution. It can overturn legislation passed by Congress through the power of judicial review. Each justice is nominated by the Executive Branch and confirmed by the Senate, and every justice serves for life. The House of Representatives has no power in the process of selecting justices.

For a moment, in the 20th century, liberals viewed the Supreme Court as a vehicle for positive social change. But lasting social change only comes from below. It cannot be handed down from the courts, and so the brief time of progressive rulings inevitably passed. Despite occasional small gains won by the Left, the Supreme Court remains what it was meant to be—a reactionary servant of power guaranteeing the destruction of left-leaning legislation.

The Supreme Court is the greatest threat to legislation born from a mass working-class movement. Popular legislation passed by Congress and signed by the President can be overturned in part or in full by an unelected body of nine people, serving a life term, tasked with upholding and interpreting an outdated and inherently undemocratic document.

If Bernie Sanders is elected in 2020 and manages to shepherd Medicare For All through the House and the Senate, the risk of the Supreme Court ruling the law unconstitutional would remain. If this occurs there would be little recourse. A constitutional amendment is the only way around the Supreme Court, and the requirements are so onerous it took the Civil War to implement recent meaningful amendments.

If all other restrictions on democracy fail the Supreme Court serves as the ultimate negation of popular policy. It is the final backstop against the will of the majority.

Similar to feudal lords who owned the land and the serfs forced to work it, today a few wealthy capitalists own the means of production that wage workers must work. If the serfs were allowed, through a convoluted process stacked against them, to vote for their lords, would we call that democracy? True democracy is only possible when workers have control over their lives, their communities, and the means of production.

Our economy is not a democracy. Workers have no say in how companies are run, how resources are allocated, or how production is arranged. Political democracy is meant to be a consolation for economic dictatorship— at least we are free to pick our leaders. But in the “Land of the Free” even political democracy eludes us.

The working class is the majority of people in the United States. An average worker spends most of their life producing for society, making society function. And yet the working class has no control over the society that depends on them to survive. What we are living under is the dictatorship of the capitalist class. They control the means of production and use the state to maintain that control. The tyranny of CEO’s, Wall Street executives, corrupt politicians, and bureaucrats decide the fate of the majority.

What is needed is a “dictatorship of the working class” i.e. a dictatorship of the majority in the form of a “workers’ republic”, a true democracy where workers have wrested control of the state from the capitalists, control the means of production, and democratically plan the economy. Democracy, freedom, liberty, equality, the pursuit of happiness are all impossible while the majority of people are ruthlessly exploited and have no control over their lives, where they are denied even the most basic political freedoms promised by liberalism. Humanity’s potential cannot be fulfilled without the emancipation of the working class. Until that day comes democracy is a reality only for the ruling elite and remains an illusion for the rest of us.

Jacob Richter weighs in on the Kautsky debate centering around revolutionary strategy, arguing for a balance of power approach.

Earlier this year a series of articles in Jacobin on the Marxism of Karl Kautsky triggered a discussion of socialist strategy. It took a while for an article on Karl Kautsky (when he was a Marxist) to come out which got past the strawmen presented by the Eurocommunist-sounding James Muldoon and the Luxemburgist-sounding Charlie Post. In his original article, Eric Blanc suggests the taking up of defensive parliamentary strategy, the basis of the Finnish Revolution, as the socialist model of revolutionary change in the most developed capitalist countries:

[Kautsky’s] case was simple: the majority of workers in parliamentary countries would generally seek to use legal mass movements and the existing democratic channels to advance their interests […] even when a desire for immediate socialist transformation was deepest among working people, support to replace universal suffrage and parliamentary democracy with workers’ councils, or other organs of dual power, has always remained marginal.

In other words, socialists should win a majority in parliament, thus provoking anti-socialist forces to move against parliament, thus triggering a massive socialist response.

There are major problems with this defensive parliamentary strategy. While it should not be stated that its conceptions of “legitimacy,” “power,” “majority,” and “support” are crude, those same conceptions are too shallow. The best of Kautsky the Marxist is not enough, not because it is not left enough but because its revolutionary centrism is not developed enough. What follows is both a fuller criticism of this strategy and advocacy of post-insurrectionary strategy in a very specific form of party revolution: the mass party-movement making the anti-capitalist rupture on the basis of majority political support from the working class.

The defensive parliamentary strategy does not acknowledge constitutional limits. Every country has a process to amend its constitution which requires much, much more than a simple majority. Even further democratization of liberal-constitutional orders faces this as a major obstacle. Whether it’s replacing elections altogether with sortition (demarchy), getting past fetishes regarding universal suffrage (which will be discussed later in the article), establishing separate legislative bodies for social policy and for economic policy, ensuring that every public official has standards of living comparable to the median professional worker, implementing multiple avenues to recall any public official where there has been abuse of office, or some other fundamental democratic change, the defensive parliamentary strategy evades the constitutional amendment question. History has shown, time and again, that small-d democratic routes to socialism are incompatible with liberalism and its insistence on the constitutional order.

The defensive parliamentary strategy does not recognize the existence of multiple kinds of majorities, whose individual distinctions are key to advocating any anti-capitalist rupture in an informed manner. There are constitutional majorities, parliamentary majorities, electoral majorities, class majorities, and of course the demographic majority. The first of these has already been discussed. The second, the very underpinning of the defensive parliamentary strategy, ignores the ordinary system of checks and balances in liberal-constitutional orders, be they bicameral legislative setups or the politically unaccountable judicial review. Blanc has already noted the need for major democratic reforms, not least because electoral majorities are not the same as parliamentary majorities.

The longer-term concern is the distinction between electoral majorities and class majorities. Without venturing into Lenin’s emotional outbursts against the renegade Kautsky in 1918, it should suffice to be stated that the defensive parliamentary strategy relies too much on universal suffrage to bring about the socialist government capable of the anti-capitalist rupture. Not for nothing did the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) arrive at the position of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) that capitalists should not be allowed to participate in elections, precisely because of the anticipation of big business resistance. If anything, given the pervasiveness of lobby money and quid pro quo arrangements today, why should they not be excluded from the entire political process altogether?

The distinction between electoral majorities and class majorities gains greater significance when non-worker classes other than capitalists are concerned. Not for nothing did Marx and Engels advocate the self-emancipation of that socioeconomic class which depends on the wage fund – the working class. Even in the most developed of capitalist economies, the various non-worker classes other than capitalists number as much as a third of the population. A defensive parliamentary strategy which somehow wins over supermajority support from these classes, yet which cannot command the majority political support of the working class, cannot be seen as the self-emancipation of the working class!

The defensive parliamentary strategy does not recognize the existence of multiple kinds of support, whose individual distinctions are key to advocating any anti-capitalist rupture in an informed manner. The relevant ones, in this case, electoral support, political support, and class support. When none other than Engels mistakenly judged the individual vote under universal suffrage to be a gauge, he did not anticipate the possibility of protest votes by individuals ordinarily not supportive of the party selected, nor did he anticipate the possibility of spoiled ballots by socialist individuals. The former should not count as political support, while the political support of the latter should be found elsewhere.

Not all political support is mere electoral support. Both Blanc and Post mentioned the need for independent organization and mass action outside parliament and the rest of the electoral arena. However, even that is not the best gauge for political support.

The best gauge is voting membership. Individual commitment to political principles, to a political program, as expressed by economic support (not necessarily financial support) and an appropriate degree of “non-activist” participation (to avoid careerism and burnout), signifies real support that a passive, periodic vote could not express.

Class support, within the context of the voting membership, necessarily entails a workers-only voting membership policy. The likes of Engels understood that the extension of voting membership to those not of that socioeconomic class dependent on the wage fund went against the principle of self-emancipation for that class. While he was a Marxist, Kautsky argued for the mass party-movement to which he belonged, the then-Marxist Social-Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), to maintain this policy, even against the likes of August Bebel and his working-class credentials!

Historically, the workers’ movement did not create bodies exclusive to itself but which met in continuous session. The concept of the continuous session has historically been the one saving grace of parliaments in relation to trade union bodies or workers councils. Meeting at this most frequent level is required to hold bureaucracies to account, which neither trade union bodies nor workers councils did.

The defensive parliamentary strategy is reductionist in advocating that only the existing parliaments are capable of meeting in continuous session so as to hold bureaucracies to account. The limitations of these establishment bodies are well known.

Instead, what is needed is a mass party-movement or class-for-itself:

It has already been asserted that the mass party-movement as defined above must have majority political support from the broader class in order to have legitimacy. Although the defensive parliamentary strategy does recognize the possibility of anti-socialist forces moving against a socialist-won parliament, as well as an extra-legal socialist response, in turn, the obsession with legal means restricts excessively the resort to extra-legal means to the very end. Legal obstacles, such as hard constitutional limits and regular checks and balances, have already been mentioned.

Legal means ought to be pursued where possible, and extra-legal ones when necessary. The degree of violence should be determined by the extent of violence committed by the opposition.

Eric Blanc’s usage of the word “center” is inaccurate. There was indeed an orthodox Marxist center, but it existed before the vulgar “center” from 1910 onwards. The orthodox Marxist center, or revolutionary center, very much included the likes of the Bolsheviks. They opposed both the strategy of reform coalitions, advocated by those to their right and the strategy of shutting down the state with mass action, advocated by those to their left. The latter strategy had its genesis in the insurrectionary general strike of Mikhail Bakunin, flowered in the violence romanticism of Georges Sorel, and continued in very diluted form in the works of Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky.

Since the original exchanges advocating for or against the defensive parliamentary strategy, the likes of Mike Taber, Donald Parkinson, Tim Horras, and Chris Maisano have furthered the debate. So have Stephen Maher and Rafael Khachaturian contributed, via Verso.

Earlier in my discussion, I outlined the fundamentals of a post-insurrectionary strategy that address the shortcomings of both the defensive parliamentary strategy and the usual insurrectionary strategy. Although not all electoral support is political support, and although not all political support is mere electoral support, electoral support remains too big an elephant to be ignored.

It is woefully true that adherents to the usual insurrectionary strategy have been reluctant quite often to step into the electoral arena (Maher & Khachaturian). Electoral participation has usually been treated as a token means to be a tribune of the people. Those even further to the left abstain altogether, leaving no opportunity whatsoever for working-class expression of discontent at the ballot box, however insufficiently “woke.”

On the other hand, it has been argued by Marxists such as Sophia Burns that there are four types of committed people on the left: government socialists, protest militants, expressive hobbyists, and base builders. Base builders who are more supportive of the usual insurrectionary strategy have identified supporters of the defensive parliamentary strategy as “government socialists.” In other words, every “government socialist” is an office-seeker.

At the beginning of my discussion, it was asserted that the best of Kautsky the Marxist is not enough, not because it is not left enough, but precisely because its centrism is not developed enough. While the broader post-insurrectionary strategy is an attempt at further centrist development overall, the non-tactical, systemic electoral approach for this strategy is one of Balance of Power.

Simply put, the Balance Of Power approach strives to achieve a legislative presence that, while deliberately insufficient for a legislative majority, is unambiguously large enough to hold the legislative balance of power. The electoral accomplishments of the Nazis in July and November of 1932 are the most notorious example of a Balance Of Power approach. Recent electoral milestones by radical “populist” right forces in the European Parliament are another example of a Balance Of Power approach. In the North American context, the Canadian New Democratic Party held the balance of power between 1972 and 1974, during the parliamentary minority government of the Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau.

The systemic application of this approach would include not just federal legislatures, but also provincial and regional legislatures as well as municipal councils.

Neither advocates of the defensive parliamentary strategy nor advocates of the usual insurrectionary strategy have taken into consideration the right to spoil ballots. Naturally, for the former, this gets in the way of office-seeking. Particular advocates of the latter strategy have carried on the electoral abstentionist line established long ago by Bakunin, in spite of the many flaws pointed out by Marx and Engels. It is no accident that ballot spoilage is considered by these people to be something that legitimizes the existing system somehow. Still, if a disgruntled voter can spoil but chooses not to spoil, said person has “no right to complain” – to adopt the conventional adage against voter abstention.

The Balance Of Power approach carries the advantage of flexible electoral organizing. Specific groups of people striving to achieve the legislative balance of power can engage in the usual electioneering. Specific groups of people who are rightfully skeptical about the electoral process can engage in spoiled ballot campaigns.

In 1900, the Paris Congress of the original Socialist International resolved unanimously in favor of illusions in municipal socialism. Not even Kautsky the Marxist expressed concerns. In fact, Rosa Luxemburg was even enthusiastic about this. Logically, the resolution extended to illusions in provincial socialism. Leaving aside the problems of opportunism, the main problem is that neither level of government can print its own currency to fund entertain illusions of “socialist achievement” at its respective level. Budget cuts from higher levels of government override illusory ambitions. “Red mayors” and “red governors,” not even those of the Italian Eurocommunist tradition, are not the answer.

Again, a systemic application of the Balance Of Power approach means achieving in provincial legislatures, regional legislatures, and municipal councils, a legislative presence that, while deliberately insufficient for a legislative majority, is unambiguously large enough to hold the legislative balance of power. Contemporaneous examples would be the city councils of Chicago and Seattle.

Jonah Martell lays out a vision of socialist electoral strategy.

In January 2018, the Democratic Socialists of America adopted an ambitious new electoral strategy. It denounced both the Republican and Democratic parties as “organs of the capitalist ruling class,” and declared that its goal was to build “independent socialist political power.” The resolution was a clear break from the strategy of DSA’s founder, Michael Harrington, who hoped to gradually realign the Democratic Party to the left.

However, the resolution did not call for DSA to reconstitute itself as an independent political party. It remained open to running candidates in Democratic primaries, and even to local chapters endorsing non-socialist politicians on a case-by-case basis. This flexible approach is helping DSA members win unprecedented electoral victories—most notably with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s stunning upset in a New York congressional primary. But it also has its fair share of detractors who argue that any engagement with the Democratic Party is misguided and opportunistic.

Whether this assessment is accurate or not, DSA’s decision to avoid an all-out break with the Democrats has a rational basis. As the organization stated before its leftward shift, “the process and structure of American elections…[have] doomed third party efforts.” The United States has perhaps the most repressive electoral system in the developed world. Most states enforce draconian ballot access requirements on third party candidates and strictly regulate the organizational structure of political parties. Meanwhile, gerrymandering by both major parties has seated undemocratic legislatures, entrenched incumbent politicians, and made many elections uncompetitive.

Perhaps most importantly, nearly all American elections are based on plurality voting in single-member districts. This system creates the media-hyped “spoiler effect” in which marginal candidates draw voters away from one of the two major parties and unintentionally help the other. In 2000, the spoiler effect made an infamous contribution to George W. Bush’s presidential victory. More recently, it helped the vicious reactionary Paul LePage win two gubernatorial elections in Maine—once with less than 38% of the vote. Over time, the spoiler effect has frightened the public away from voting for third parties, contributing to their near-total marginalization.

Only extensive reforms can remove these obstacles to third party success, but the Republican and Democratic parties are both firmly invested in the existing political order and will never willingly change it. To most observers it seems like a hopeless situation, and even some socialists have called on the American Left to accept that we must work within the two-party system.

We should reject this defeatist outlook. The socialist project has always strived to “win the battle of democracy,” to achieve universal suffrage and other reforms that challenge the capitalist class. If our goal is to build a principled socialist movement with revolutionary ambitions, the very idea of two-party rule should be noxious to us and we must fight it tooth and nail. We need to conquer the ballot—to force a democratizing overhaul of the American electoral system.

And in Michigan, a grassroots campaign is showing us how.

In December 2017, a Michigan activist group called Voters Not Politicians (VNP) announced that it had collected enough petition signatures to put a novel initiative on the ballot in November 2018. If it is passed, it will alter the state’s redistricting process by stripping the Republican-dominated legislature of its power to draw congressional and state legislative districts. Instead, redistricting will be conducted by an independent panel of citizen volunteers, selected by lot in a manner similar to juries. In a state like Michigan where gerrymandering is rampant, this would represent a groundbreaking democratic reform.

The success of the signature drive is particularly impressive because it was an all-volunteer campaign run on a shoestring budget, without a single paid petition circulator. Over 425,000 people have signed the initiative and polls indicate that a clear majority of Michigan voters support it. If they are given the chance, they will almost certainly pass the initiative—which is why its opponents, backed by the state’s Chamber of Commerce, fought bitterly to block it in the courts. In July this year, they lost, with the Michigan Supreme Court ruling that the measure would remain on the ballot in November.

Despite right-wing attempts at obstruction, the lessons of the VNP campaign are clear. Even with limited resources, grassroots organizers can use ballot initiatives to bypass establishment politicians, fight for electoral reforms, and win.

Twenty-four states, Washington, D.C., and countless local governments allow for some form of a citizen-led ballot initiative. If one group in Michigan could mount such an intriguing campaign, what could a national organization like DSA accomplish if it adopted a strategy for electoral overhaul through ballot initiatives? What kind of electoral reforms should socialists demand and which are the most important?

If we want to use ballot initiatives as a springboard for mass mobilization, we should emphasize broadly democratic reforms like the Michigan anti-gerrymandering measure. American voters on both the Left and Right are acutely aware of gerrymandering, and they universally hate it. They also hate the influence of corporate money in politics, so we should demand extensive public financing of elections to make races more egalitarian. If we tap into popular rage against the political elite, the public will increasingly view socialists not as a threat to democracy, but as its greatest champions. We could establish ourselves as a unique force willing to challenge both Republican and Democratic hacks, winning over a mass constituency not only from liberal demographic groups but also from traditionally conservative ones.

The same principle applies to reforms that more directly challenge the two-party system. Over 60% of Americans and 71% of Millennials feel that the United States needs a competitive third party. With their support, we should push initiatives to scrap unfair ballot access requirements and deregulate the structure of political parties. Ending plurality voting in single-member districts will be another crucial task. In state legislatures, we could implement proportional representation (PR), an electoral system that gives political parties representation directly tied to their percentage of the vote. Under PR, even single-digit support can often guarantee a party at least a few legislative seats. For a fledgling socialist group seeking a political foothold, this would be a godsend. There are many different types of PR—some of which would be more palatable to American voters than others—but all would represent an improvement over the current system.

At first glance, it might even seem possible to pass an initiative in a given state to have its members of Congress be elected with proportional representation. Nothing in the Constitution forbids a state from doing this. But sadly, federal law does: since 1967, it has mandated that all House representatives be elected in single-member districts. This means that at least in the beginning, our efforts to win proportional representation will have to focus on state legislatures and local governments.

Thankfully, federal law does not require that representatives be chosen by plurality vote. This opens up the possibility of an alternative federal-level reform: instant-runoff voting, which allows voters to rank multiple candidates in order of preference instead of choosing only one. If no candidate receives a clear majority vote, a series of simulated runoffs are conducted until one candidate emerges as the victor. Instant-runoff voting does not produce proportional representation, but it helps third-party candidates compete by largely eliminating the spoiler effect. Last year in Minneapolis, where instant runoff has been used for nearly a decade, Ginger Jentzen ran for city council on a Socialist Alternative ticket, with additional support from the local DSA chapter. She won 34% of the vote in a four-way race, with more people selecting her as their first choice than any other candidate. Jentzen did not win the election, but her performance was excellent when compared to the single-digit results of most American third party campaigns.

Working state by state, we could implement instant-runoff voting for both House and Senate elections. Just a few successful initiatives could have tremendous political implications: Florida and California both allow ballot initiatives, and together they account for almost 20% of the seats in the House of Representatives.

In summary, our electoral reform program should raise five key demands: citizen-controlled redistricting to counter gerrymandering, public financing of elections, elimination of restrictive ballot access laws, deregulation of political parties, and an end to plurality rule in single-member districts—which could entail proportional representation in state legislatures and instant runoff voting at the federal level. Taken individually, these reforms would be policy tweaks that any liberal technocrat could propose. But if we push them collectively, as part of a broader radical movement, they could revolutionize working-class politics and smash the two-party system forever.