Colin Drumm’s “Beyond Denial and Abstinence” argues that we should define economic growth in terms of meeting human needs, as opposed to the prevailing definition centered on ruling-class interests. This argument is important when responses to climate change tend to center around issues of economic growth as either positive—as something that needs to be decoupled from carbon emissions—or inherently negative—as something that needs to be reversed. While we, the Cosmonaut Editorial Board, would argue for a more drastic economic change than the policies proposed at the end of this article, we believe that its general arguments are an important jumping-off point for a debate about how we understand economic growth in the context of climate change.

I am often, as I suspect so many of us are, paralyzed by an overwhelming sense of impending loss. The enormity of climate change and what it means for us and all that we hold dear induces in me physical anxiety that sometimes makes it almost impossible to think. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes once wrote that thought, or at least most thought, was guided by a passionate intention: our thinking, he said, is put into order by a desire. There is a desire, this desire is in the future, and it is in the service of this desire that we do our thinking. We think that we can get what we want. A simplistic model, no doubt. But I cannot help but notice that it offers, in its way, a diagnosis of my predicament: it has become impossible to think because it has become impossible to imagine a future that has any room for my desire in it, a future which “holds space” for my desire and thus makes it possible, in Hobbes’ terms, to think my way towards it. When I think of the future it has become impossible to think of anything but loss. I do not think I am the only one.

Conceived of in this way, it becomes possible to think of the problem of climate change as the problem of what another philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, would have called the problem of “sad affect.” An affect, for Spinoza, is not only a “feeling” or an “emotion” but also a relation to another entity: a sad affect is caused in me because I am interacting with another entity in such a way that my power, or my ability to produce and reproduce the conditions of my own existence, is reduced. We feel sad, that is, because there is something out there influencing us and making us less powerful, which means that we are less able to continue to be and to flourish. This makes us anxious. Climate change is a sad affect in precisely these terms: it is something “out there” which we relate to in such a way that it freezes our thinking and makes it less and less possible for us to react constructively to what is already happening all around us. This is a very dangerous situation. We are all, even those of us who claim to “believe” in climate change, a bit like a deer caught in the headlights of the future, and we must find a way to break ourselves out of this spell.

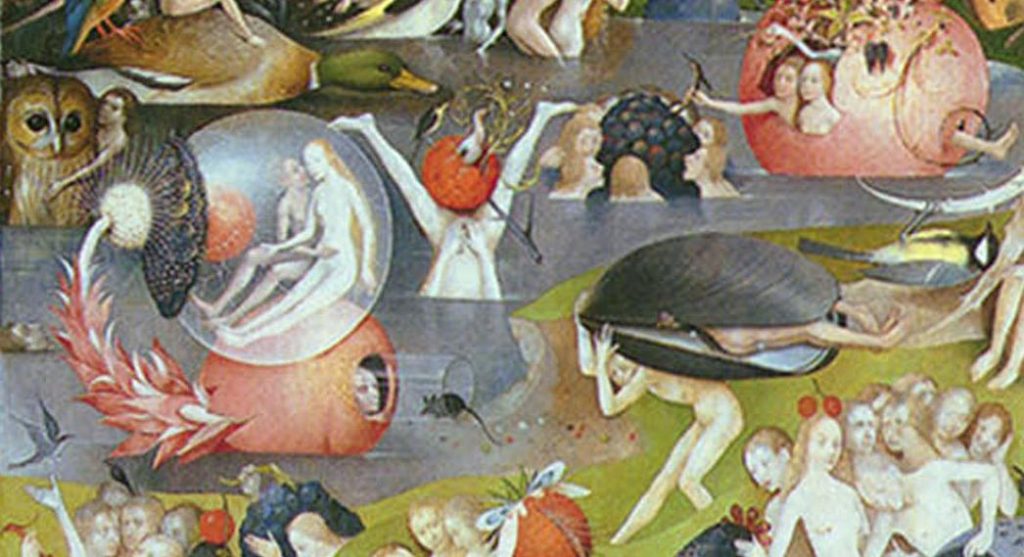

The issue, I think, is that we are in the habit of thinking of climate change as punishment for our sinful desires, and are thus caught in a trap “between denial and abstinence” in the way we approach the problem. On the one hand, denial: if climate change is real, and it is caused by our sinful desire, then that means I will be asked to give up my desire – not to drive and not to eat meat and so on – and I ward this off by pretending that climate change does not exist, or that it is not as bad as all that. I become a climate change denier in order to protect my desire. And on the other hand, there is abstinence: if climate change is real, and it is caused by our sinful desires, then I must renounce my desire by abstaining from consumption of various kinds in the hopes that this repentance might lead us to be forgiven and thereby saved. If we can just renounce enough of our desire, then climate change doesn’t have to happen: I give up on my desire in order to become a climate change abstainer. The problem is that no matter which side we take – denial or abstinence – climate change makes the future of desire impossible: either we give up what we want in order to save the world, or the world ends, in which case we can’t get what we want either. And when desire becomes impossible, we are overwhelmed by sadness and we cannot think.

Can we, then, refigure the problem of climate change in our political imagination such that we can escape from the trap of overwhelming and paralyzing sad affects? To do so would be to conceive of climate change in the mode of gain, rather than that of loss, to think of what it can enable us to desire rather than what it forbids us from desiring or shames us for desiring. How can our fight against climate change be guided by the passionate intention for a new and better world, rather than by sadness for a dying one?

To answer this question, we need to understand more precisely what is meant above by a “sinful desire.” We can give it a name: “economic growth.” The problem of climate change has generally been framed as a problem about the relationship between, on the one hand, the total carbon budget of the planet, and, on the other, the rate of growth of the economy. What capitalism desires is economic growth, and this desire is sinful: it is sinful because it seems to produce structural immiseration of some portion of its population alongside structural affluence of some others (the more traditional “paradox of poverty” in political economy), and it is also sinful because it burns carbon and thus threatens the continued availability of ecosystem services on which our lives depend. Debate about climate change, therefore, is generally structured by the question of the relation between the sinful desire, economic growth, and the consequences of that sin: climate change. This debate can, therefore, be understood in theological terms. Conservatives, for example, have tended to deny the existence of sin in the first place: economic growth is desire, sure, but there’s nothing sinful about it, because the poor deserve what they get and climate change isn’t real. They further argue that any attempt to fight climate change must necessarily harm economic growth, and that we therefore shouldn’t do it.

Mainstream liberals, on the other hand, have tended to argue that growth and carbon can be reconciled: that we can achieve a state of what is called “absolute decoupling” in which a growing economy is combined with carbon emissions falling in absolute terms. The first strategy for achieving this reconciliation is what we might call a logic of indulgence, exemplified by the sale of “carbon credits:” an indulgence in a sinful desire (flying on an airplane, for example) can be “offset” by paying money to a philanthropic organization which, supposedly at least, uses it to sequester carbon elsewhere. The second strategy revolves around a technological optimism: the idea that economic growth produces technological progress, so that if we grow the economy, technology will improve, and improved technology will allow us to solve the carbon problem.

Those to the left of the mainstream liberals – call them ecosocialists – have rightly tended to be suspicious at this optimistic framing of things. They point out that the sale of carbon indulgences and schemes like carbon cap-and-trade may exacerbate, rather than ameliorate, the social justice implications of climate change, and they view the liberals’ narrative of technological optimism with justified suspicion: such rhetoric is just as likely to be a veil over cynical profit-seeking as it is to be in the service of a genuine attempt to confront the problem. The ecosocialists thus agree with the conservatives that it is impossible to fight climate change without ending economic growth, but simply take the opposite conclusion: that we must “degrow” the economy in order to save the planet.

What I have done above is to describe the problem of climate change as a version of what theology would call “theodicy” or the problem of evil. Simply put, the problem is that if God is omnipotent and benevolent, then why is there suffering in the world? Why wouldn’t God just make the world such that nothing evil existed in the first place? If economic growth has become a kind of “God” of our world, a God which grants us each day our daily bread and which we must serve if we are to retain his good pleasure, then the problem is why “sin” (that is, poverty and ecological collapse) still exist in the world. The conservative response is a kind of “low church” or protestant response: it says, the sacrifice of Christ means that we are in a state of grace, we have already been forgiven for our sins, so there is nothing to apologize for, and everything that happens is part of God’s plan, anyway. The mainstream liberal response is, by contrast, a “high church” or perhaps a Catholic response: it says, yes, we are always in danger of stepping into sin as a result of our desire, at every moment, but this does not mean you have to give up your desire – all you have to do is make a sacrifice, in the form of a monetary indulgence, to a churchly bureaucracy which will fix things by “balancing the books.” The ecosocialist response, finally, is a gnostic one: it says, in fact, the God of economic growth who made this world of capitalism is not a true God but a false, evil one, not God at all but a mere demiourgos, and the only way out of a world which has been irredeemably corrupted by its worship is to renounce this false God entirely. If economic growth is “what we want,” then we have no other choice but asceticism: the voluntary renunciation of desire aimed at a total escape from a world in which, as it is sometimes put, “no ethical consumption is possible.”

In framing the problem in this way, I do not want to take up sides for one theodicy or another. Rather, my goal is to see if it is possible, once we understand the problem as being the problem of theodicy, to step outside of it entirely and think about things in a radically different way. How can we think of a way to approach the climate change problem that would be neither denial, nor indulgence, nor abstinence? If we could, we might be able to put desire back into the future, so to speak, and escape from the trap of “sad affect” in which we cannot think because we have lost the capacity to find a place for our desire in a future we can believe in. If we could, we might regain the ability to face the future with a renewed sense of purpose and yes, perhaps, even a feeling of joy. And this would make us immeasurably more powerful. So. How to begin?

I want to propose, in the remainder of this essay, that the problem can best be attacked not by attempting to resolve the contradiction between carbon and growth but by contesting the social construction of the category of “growth” in the first place. That is, while the amount of carbon in the atmosphere is simply an objective fact that can be measured more or less precisely, what we call “economic growth” is not an objectively real category. It is, essentially, an arbitrary accounting framework that can be, and has been, constructed in radically different ways over the relatively brief history of this concept’s existence. The Good News that I have come to offer is that there is, objectively speaking, no such thing as “economic growth,” and that because it doesn’t exist, we don’t need to worry too much about whether or not we have to give it up or whether it can be redeemed. In other words: “we got ninety-nine problems but economic growth ain’t one.” Let me elaborate upon and defend this assertion, and then conclude by offering an alternative.

As Brett Christophers has argued, there is nothing “natural” or “inevitable” about the way in which the national income accounts (GDP) construct the category of “economic growth.”1 Following his argument, I suggest that the “fake objectivity” of GDP statistics can be understood as being the consequence of three “ideological slippages” in which normative claims are falsely represented as objective ones. Our quantitative and descriptive claims about the growth of the economy depend in an irreducible way, it turns out, upon prior normative or moral assumptions about how the world should be. I will focus on three “slipping points” at which normative or ideological claims are presented as objective or scientific ones, and thus produce the illusion of economic growth as a natural category: 1) the slippage between growth as the production of goods and services vs. growth as a return on investment, 2) the “banking problem,” or the question of the difference if any between “real” and “fictitious” capital and how to represent banks in national accounting terms, and 3) the problem of inflation and “hedonic value.” The upshot of this argument, to which I will return in closing, is that the “degrowth” analysis of the climate change problem is founded upon a mistaken premise: that the situation we are currently faced with is one of compounding economic growth combined with an accelerating carbon burn. Instead, I will argue, most if not all of the apparent “economic growth” in the United States for a number of decades is simply an illusion produced by a completely arbitrary and highly misleading accounting system. Measured in a more honest way, we are already, and have been, in a situation of declining economic growth in real terms. We are, therefore, in fact faced with the rather different scenario of an accelerating carbon burn accompanied not by economic growth but rather by an economy which is stagnant and declining and which has, indeed, been this way for some time. This change in the underlying assumptions that frame the problem has, as I hope to demonstrate, important consequences for the question of “what is to be done.”

First slippage. According to what might be called the “liberal constitution” — in the older sense of the word, not as a written document setting down fundamental rules, but rather a sort of governing sensibility that animates a political order — GDP is the central proxy measure for the “success,” and therefore the legitimacy of, a government. GDP is assumed to be “what everyone wants,” to be a universal consensus good, and thus functions as what Jean-Jacques Rousseau would have called the “General Will” – an object of desire which is good for everyone and to which, therefore, individual interests should be made to bend. It becomes the job of the government, therefore, to serve GDP: the government is seen to be a kind of fiduciary steward of “the economy,” the growth of which is supposed to be what is good for everyone without being bad for anybody and which can therefore be seen as a proxy for the interests of the people as such.

But there are some obvious problems with conceiving of the maximization of GDP as the ethical foundation of state legitimacy. For one thing, there is the question of growth of what and for whom? We only have to open our eyes to the world around us to see that there are many people who do not seem to be benefitting from “economic growth,” and who are in fact being actively harmed for it: people who are pushed into homelessness as a result of gentrification and rising rents, for example. We might begin to suspect that “economic growth” really has much less to do with the question of whether the economy is serving the people who depend on it and much more to do with the question of whether investors will receive a good return on their investments. We might suspect that “economic growth” is really more about whether rich people get richer than whether all people in general experience a qualitative increase in the value of goods and services available to them. The fact that mainstream media commentators often use the phrase “economic growth” when what they are really talking about is the value of equities on the stock market is a symptom of this ideological misdirection. But we will need more than a suspicion. We need an analysis.

This brings us to the second slippage: the banking problem. Simply put, this is the “problem” that when banks are represented in the same way as other sectors of the economy in the national income accounts, what they show is a negative contribution to the total product of the economy. This is because the net interest payments accruing to the financial sector – the difference between what banks pay to borrow money and what they charge to lend it – seems to be simply a transfer of money out of the “productive” economy where it might have been invested in producing goods and services. When banks are treated in the most straightforward way in the accounts, they show up as being nothing more than a “drain” on the real economy, and in fact this is how they were usually treated in accounting prior to the post-War period, in accordance with the distinction that was made in classical political economy, from Smith to Marx, between “value” and “rent.” According to this way of thinking, the “real” economy produces value, while the “fictitious” economy doesn’t produce anything but only extracts rents from other sectors that do.

Since the introduction of the first international accounting framework by the United Nations in 1953, GDP measures have attempted to “solve” the banking problem in various ways so that the financial sector could be represented as making a productive contribution to the national product. The SNA 1953 framework represented the net interest payments to banks as an “intermediate product” supplied to other sectors of the economy as inputs: producing a refrigerator could, in other words, be said to “consume” bank credit in the same way that it consumes aluminum, and the banking sector’s contribution to total product could be represented as such. This method was politically controversial, however, as it increased the imputed product of the banking sector at the expense of other sectors, and it also had the curious implication that the product of a sector would vary according to its capital structure, or whether it was funded by debt or equity. An alternative framework, the SNA 1968, was introduced that solved this problem by taking an even further step into absurdity, inventing a wholly fictitious notional sector of the economy that could be said to “consume” the product of the financial sector without thereby detracting from any of the others.

These two frameworks were superseded in 1993 by a new System of National Accounts which, finally, succeeded in defining finance as unambiguously productive. It did so by disaggregating the lending and borrowing activities of banks, and treating each of them separately as a productive function in their own right. Rather than seeing banks as collecting a spread between their cost of funds and returns and lending, that is, this new framework conceived of them as making a profit on both sides by introducing the concept of the “reference rate” or the “pure cost of borrowing funds.”2 Banks were understood to make a profit, and thus a contribution to national product, on the borrowing side by borrowing at a rate below the “pure cost” of borrowing funds, and on the lending side by lending money at a rate above it. Since interest rate spreads are understood in financial theory as being compensation for risk, this framework answers the question of what banks “produce” by representing them as being paid for the service of assuming financial risk by moving it off the balance sheets of their counterparties and onto their own. The experience of 2008 shows, however, that we have good reason to doubt this justification since the doctrine of “too big to fail” asserts that the state is under an implicit obligation to assume the systemic risks of the banking sector. If the state pays to bail the banking sector out when its risks go bad and then offloads this payment to the population through austerity, how can it still be possible to say that banks provide a service to the economy by assuming its risk?

There are more details to this history, which are quite interesting in their own right, but our present purposes will be served by this brief summary. The point I want to make here is simply that the notion of “GDP” is only about 65 years old, and during this history it has undergone some fairly drastic changes revolving around the question of whether banks should be understood as a productive sector of the economy and how to represent them as such if they are. It is only by doing this, crucially, that we can show “growth” in the figures at all: if we accounted for the financial sector in the way it was done in the early 20th century, by treating banks just like any other sector of the economy, then our figures would say that the economy has not grown, or has not grown very much, or has perhaps even been shrinking, for something like the last 40 years. While some critics from the left, the economist Michael Hudson for example, have advocated reviving the value/rent distinction from classical political economy and thus redefining finance as inherently unproductive, we do not even need to accept the rather dubious and moralizing claim that financial activities are essentially and inevitably “sterile” to doubt the legitimacy of counting, by definition, all profits accruing to the financial sector as a real contribution to the total productive output of the economy. Certainly, it seems intuitively plausible that financial activities might, at least in some cases, represent a pure parasitic burden on the economy and thus not a contribution to a product at all but simply a form of rent or extraction.

Thus, showing growth at all in the national accounts requires that we make certain assumptions rather than others about the productivity of finance. But this is only speaking in nominal terms: about the difficulties involved in measuring the size of the economy in present dollars. This brings us to the third and final slippage: the problem of inflation. We are accustomed to being presented graphs of various economic phenomena measured in graphs of dollars “adjusted for inflation,” with the implication that this is a trivial or at least completely technical operation which must be carried out in the background before we begin to think about what we are looking at. But there are, in fact, deep conceptual and even political difficulties involved in the construction of a “deflator,” or an index of the value of money over time which allows the “nominal” prices which actually physically exist in the world to be normalized to an ideal standard of “real” prices which remain commensurable with themselves over time. The first and most obvious problem is that the construction of the deflator requires the construction of a consumption basket: we need to imagine an ideal person who consumes a certain basket of goods and then measure the change of price of this basket over time. Since we are concerned to ask about the relationship between economic growth and carbon emissions, we need, in order to compare their relationship quantitatively, to construct a deflator for the period of about a century-spanning from the emergence of the petroleum economy in the early 20th century to the present day.

As Robert J. Gordon has illustrated quite forcefully in The Rise and Fall of American Growth, the construction of such a “hundred-year deflator” is faced with the dizzying task of organizing the sweeping and revolutionary changes in technology and standard of living that took place during this period. In order to construct the hundred-year deflator, we need to actually produce a couple of dozen different consumption baskets, a new one for each time a major new innovation is produced or when new products replace old ones and then stitch them together to produce the illusion of a continuous series. We have to ask, that is, not only what happens to the value of money as goods get cheaper or more expensive, but what happens to the value of money as it becomes able to purchase qualitatively new goods or goods which have improved in quality. The construction of the deflator thus requires a qualitative — and therefore normative and value-laden — assessment of not only what counts as “a good” but also how good it is. The most notorious and commonly cited example of this problem is the television: as the number of pixels in the television increases, the “hedonic value” of the television rises, which means that the value of the dollar in the inflation measure rises with it. When someone reports to you what the rate of inflation is, therefore, they are also implicitly ordering you to care about televisions and their number of pixels and to accept that they matter for determining the value of money. Now, I don’t know about you, but there are few things in the world that I care about less than televisions and their pixels, so this kind of thing makes me a little suspicious.

I’ll return to this problem of hedonic value adjustment in a moment, but first I want to strengthen the point by giving an example that cannot possibly be dismissed as a quibble. It is bad enough that it may be somewhat difficult to decide which goods count and how good they are, but there is, even more troublingly, an ambiguity about whether some “goods” might not, in fact, be “bads.” It is, in other words, not only a question of magnitude but also of sign which must be decided by the normative accounting process by which a deflator is constructed. Let me begin with a more obvious example before proceeding to some subtler ones. A point around which the above discussion of the banking problem hinged was the relation between the financial sector and non-financial firms: should the money flowing out of the non-financial sector towards the financial sector be understood as a transfer payment or instead as representing the provision of an intermediate good, just like coal or steel? What we did not consider, at that point, was the question of how to understand income accruing to the financial sector from households directly: are these payments to be considered a transfer payment (i.e. a rent) or as a final good, or something which households consume and enjoy and benefit from? Because, in the standard accounting, finance is defined as productive, it is treated as the latter: everything that the household sector pays to the banking sector is, by definition, a payment for goods rendered. To define things in this way is to deny outright and on a priori grounds the mere possibility of “predatory finance,” or credit which does not improve the ability to debtor to repay it and is thus very difficult to ever escape. Might it not be more reasonable to see at least some forms of consumer finance as more of a way to extract money from people who don’t have any, than as the provision of any real good or “service”? The ever-escalating cost of the insurance needed to pay arbitrarily inflated costs of medical care in the United States is only one obvious example of a situation in which we should be leery of assuming that all forms of consumer finance are actually “goods.”

We do not, however, need to appeal to the especially problematic financial sector in order to find cases in which “goods” might be better understood as “bads.” The automobile is one example. Now, there’s no question that a lot of people like cars, find them exciting and aesthetically pleasurable, enjoy being able to go places in them, and so on. From this perspective, the automobile is a good: you pay money for it, you get the good, that’s growth! But this perspective can be turned on its head if we consider the idea that owning an automobile is now, at least for many people, a requirement for participation in society in a way that was not the case for people who lived in the past because they inhabited built environments which did not take the ownership of cars for granted. Is being forced to buy and fuel and service an automobile so that you can sit in traffic while commuting to a job across low-rise sprawl something that you get to do with your money, or is it something that you have to do with your money? If it’s the latter, the automobile might start to seem more like a tax than a good, a suspicion which is hardly allayed by the fact that many cities intentionally dismantled their public transportation infrastructures at the behest of automobile manufacturers in the early 20th century. Or suppose, in another example, that a new kind of laundry detergent is produced which costs half as much as the old kind. Since this makes the value of the dollar go up, it will show up as growth in the inflation-adjusted national income accounts. Now suppose, also, that this new detergent, unbeknownst to anyone, happens to give you cancer. The medical care you receive to treat this cancer will also be treated in the accounts as growth, since it’s a service that you pay for and thus counts as a good! In this case we have not only what mainstream economics calls a “negative externality,” or a cost which is not accounted for in the price of a good, but a negative externality which is actually counted as a good in another section of the accounts. We thus have a system of accounting in which the production of sickness is counted as a good and in which the improvement of the overall level of health of the population, such that it consumed less healthcare, would be counted as an economic disaster. While this situation may indeed be “growth” in the sense of providing elites with the opportunity to accumulate assets, it cannot, with any honesty at all, be counted as an increase in the amount of real goods and services produced by the economy.

All of this is, I hope, enough to demonstrate the point that all possible measures of “economic growth” are not natural categories but rather normative, value-laden, and politically contingent constructions, which are, most fundamentally, designed to provide a theoretical legitimation of the status quo rather than to faithfully represent anything that is actually going on in the world. I will, therefore, leave my critique here, and turn to a more important question: what is to be done? The climate crisis makes it unavoidably obvious that the maximization of GDP as it is constructed is no longer satisfactory grounds for the legitimacy of the state: what good is it that the state brings us a higher GDP if it doesn’t act in order to ensure our very survival? Very well — but then what? What should we do? My answer, in a slogan, is that any serious response to the crisis must be prepared to “seize the means of accounting” and impose new frameworks for measuring inflation and economic product which are aligned with, rather than opposed to, the necessity of protecting and cultivating essential biosphere services. That is, we can, if we gain control of the government institutions whose job it is to define and produce these statistics, simply order them to create a measure to replace GDP which goes up when we do things that save the planet, by construction. Since there is no particular reason that we have to measure growth and inflation in the way that we do, there is no particular reason that we cannot simply decide to measure them in a radically different way. To produce such a measure in all of its details would be well beyond the scope of this essay, so instead, I will close by putting sketching an outline of what I feel would be the most relevant considerations.

First, let’s return to the problem of “hedonic value adjustment” in the calculation of inflation statistics. According to the theory that governs the construction of these measures, an improvement in the quality of a good must be measured as deflation, or as an increase in the value of the dollar since you can now get a better microwave or a better car or a better computer for the same price. Some economists, of late, have even gone so far as to argue that inflation is overestimated because it fails to take into account how many apps our smartphones have on them, and thus how much-increased value we get out of owning them. Thus, the inflation statistics are very careful to try to capture and incorporate all of the “upside” of the fossil economy in the sense of representing the way in which modern people seem to be able to “enjoy” a number of qualitatively novel good that were unavailable in previous epochs. But these statistics do not incorporate the downsides of the fossil economy in the same way. For example, consider two houses which are otherwise identical, with all the same faucets and all the same windows. However, when you open the faucets in one house, clean water comes out, while the faucets in the other house produce only a reeking brown ooze. Open the windows in the first house, and clean air comes in, while doing the same in in the second house gives rise to wafts of acrid, toxic smoke. Surely, for any reasonable person, this would qualify as a severe hedonic value impairment: but inflation statistics make no mention of such phenomena. Rather, to the extent that it spurs the sale of bottled water and air masks, such a situation would only be counted as yet more growth. Another example is that of produce: while monoculture and factory farming have produced a secular decline in the levels of nutrition in our food, and thus our health. While it would be reasonable to suppose that a tomato with less vitamins in it, or a tomato which has been bred for color at the expense of flavor, should be “hedonically adjusted” downwards in value, this sort of consideration plays no role in the accounting. But it could. If we took into account the negative hedonic value adjustments that accompany industrial monocultures and the fossil economy in assessing the changing “real” value of the consumption basket, we would produce much higher estimates of inflation and thus much lower estimations of inflation-adjusted growth.

Second, the banking problem and the question of inequality. The modern method of accounting assumes, purely by definition and by means of extremely creative accounting, that all financial activities must be productive and all revenues accruing to the banking sector must be payments for some good which the banking sector has provided. Now, our problem here is the truth almost surely lies somewhere between the classical view that banking is sterile and the modern view that all banking is necessarily productive. While it seems obvious to me that much financial activity, especially in our own time, is more or less purely parasitic, it also doesn’t seem quite right to deny flat-out that the financial sector “does something useful.” Indeed, the attempt to distinguish between productive credit and predatory credit is an old problem, perhaps even one of the oldest problems in legal history: while it was generally agreed that there was or should be a difference, lawyers and theologians have labored for millennia attempting to put their finger on exactly what that difference was. I therefore disagree with Hudson and others who call for a revival of the distinction in classical political economy between value and rent, on the grounds that the legal questions involved are simply too thorny.

Instead, I propose to sidestep the problem by recognizing that what is really at issue is not the inherent morality of any particular financial contract but rather the role that the financial sector has in driving wealth inequality. Wealth inequality is not only, as I believe and as you should too, a bad thing in itself, but a driver of climate change due to the fact that the propensity to burn carbon has been shown to vary linearly with income — as opposed to life satisfaction, for which additional income has marginal returns. 100 dollars means much more to a poor person than to a rich person, in terms of how much it improves their life, but the amount of carbon they end up emitting as a result will be about the same.

The real problem with the financial sector, then, is that it redistributes money away from the poor and towards the rich, who use it to squander more and more carbon in an increasingly vain effort to become slightly more happy (riding helicopters to the tops of mountains to take selfies, e.g.). Rather than attack the financial sector directly by wading headlong into the quagmire of attempting to legislate the difference between a speculation and a hedge, therefore, I propose that we simply attack wealth inequality directly by normalizing GDP over the Gini coefficient. This would have the effect of counting growth at the bottom as “more” than growth at the top, with the effect that progressive redistribution would “count” as growth in itself. While this aspect of the proposed accounting framework would not contribute to reducing the total amount of carbon emitted directly, it would help ensure that the carbon we do emit is used more efficiently to promote the well being and life satisfaction of the mass of the population rather than of an elite few. It would, that is, improve the ratio of “happiness per ton,” as well as helping to ameliorate, as a good in its own right, the deleterious and disruptive effects of rampant inequality on society.

Third: inflation statistics should be “adjusted for climate change” not only through the negative hedonic value adjustment of existing goods, but by the introduction of a fictitious accounting entry representing a basket of non market biosphere services into the consumption basket. (If the economics protest at this, we will remind them that the SNA 1968 introduced a wholly fictitious sector into the economy in order to justify the productivity of finance, and that that they are not the only ones who can play at such games). This can be accomplished simply by having the government issue everyone a sum, say a thousand dollars, and then immediately taxing it back in the form of a mandatory fee to a public biosphere services utility. This would therefore be counted as an item in the consumption basket without impacting the consumer’s flow of funds in any way, and its value could then be pegged to an index of air quality, water quality, biodiversity, and so on. If the index declined, then this would show up as inflation, since the same fee was being paid for a worse service, and that would negatively impact the growth figures. If the index went up, however, this would count as deflation and thus a contribution to growth.

Fourth: long-term debt markets should be forced to account for the risk of climate-change driven disruption by the introduction of “mark-to-climate” accounting. As I write in August 2019, the major financial news is that the yield curve has inverted (meaning that investors, anomalously, have a preference for long term debt over short term) and that the yield on the 30 year Treasury bond has dropped below 2 percent, which would be a jaw droppingly low figure were it not much higher than current rates in peer economies around the world. Since financial theory takes yield or interest to be a payment for risk, this means that financial markets currently see the middle term future as much less risky than the immediate present, which is a curious implication at a time when forests are burning over the world from the Arctic to the Amazon. Surely the 30 year time horizon cannot be so un-risky as all of that, and it is therefore hard not to get the impression that the financial markets themselves are in a state of intense climate change denial.

I propose, therefore, that “mark-to-climate” accounting should to seek to force debt markets to reflect climate reality in two ways. The first is that since bond markets play, or at least seen to play, a disciplining function in the fiscal activity of the state, all bondholders should be paid a premium upon expiry which varies with the biosphere services index proposed above: the higher the index goes, the higher the premium, which might in addition become a haircut should the index fall below a certain threshold. This would incentivize bondholders to allow states to borrow cheaply in order to pursue projects that improve the index, and disincentivize them from punishing states for engaging in such activities. The second main prong of mark-to-climate accounting would be the construction of a “climate chaos” index which measured the volatility of a basket of indicators like temperature, rainfall, and so on, accompanied by the requirement that financial institutions purchase insurance against it. This can be justified on the grounds that the doctrine of “too big to fail” offloads systemic financial risk onto the state as a liability, and because climate change increases the risk of systemic social and financial failures, financial institutions should have to pay more for this implicit insurance policy the more erratic the weather gets. These institutions would therefore be disincentivized from funding economic activity that fueled climate change and therefore raised their premiums, and incentivized to fund activity that stabilized the climate in an effort to reduce them.

It is my hope that the foregoing is enough to show that such a project is not only possible, but eminently practical, and open to a great deal of flexibility: many more proposals along the lines of those above could be given. The most important point I wish to convey here is that the apparent contradiction between “growth” and an ecological future has nothing to do with anything inherent in any supposed “laws of economics.” This so-called problem of growth is not actually a problem at all, but an ultimatum, issued to us by those who would rather see the world burn than allow their power and wealth to be diminished. We must refuse to take this ultimatum at face value, as the liberals do when they seek to show how the fight against climate change can be reconciled with growth, or as the ecosocialists do when they argue that growth is an objective thing which is the source of our problems and which we must therefore oppose. It is, I think, a matter of basic strategy that the best response to an ultimatum is another ultimatum: the demand that we must not count what the economy gives us separately from the continued existence of a world in which we could enjoy it. In this way, perhaps, we can once again make the future a place where desire is possible.

Seize the means of accounting! We have a world to win, and nothing to lose but our despair.