Djamil Lakhdar-Hamina examines the labor theory of value and references philosophy of science to defend it from critics. Features a reading guide to works on the philosophy of science, Marxism, and their relations.

The epistemological and scientific foundation of classical political economy was the “labor theory of value” (LTV). Perhaps a more fitting description is the “labor law of value.”

The LTV predicts that the prices of commodities vary proportionally with their labor-content. If a commodity contains “more labor” than another, then in all probability the first will have a higher price. The LTV makes substantial law-like claims and is not a moral proposition.

Marx did not discover the LTV. However, he did make specific contributions to the theory, including, but not limited to, the hypothesis that labor is only represented as exchange value in societies with private ownership and atomized production for exchange, the distinction between labor and labor-power, and the concept of surplus value as functionally prior to its division between profit, interest, and rent.

Attack on the Labor Theory of Value

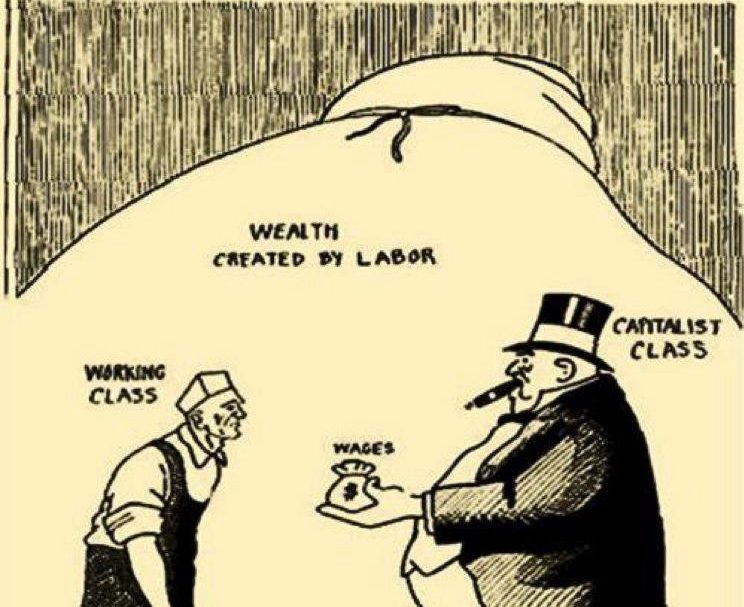

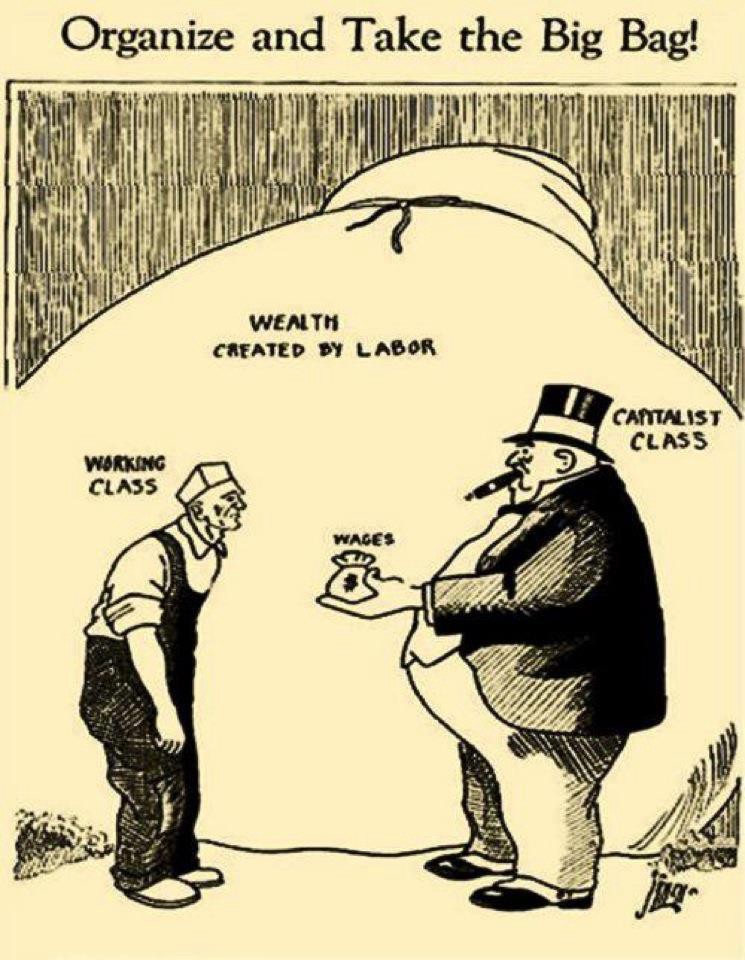

Since the publication of Capital, the labor theory of value has been closely associated with socialism. For this reason, it became a major project of orthodox economists to “refute the labor theory of value.” With the rise of marginalism and the notion that prices were grounded in the subjective appraisals of individuals, orthodox economists had a political apologia and substitute theory.

The first criticisms of the labor theory of value were logical refutations of the supposed fallacies in the transformation of labor-values to prices of production. The first version of this critique was made by the Austrian economist Bohm van Bawerk. In 1895 van Bawerk became minister of finance. It is not a coincidence that, in 1896, he published Karl Marx and the Close of his System to challenge the rising socialist movement.

Essentially, the argument was that the premise of Marx’s theory implied a contradiction, that by a reductio ad absurdum the theory was logically contradictory. More specifically, the presupposition of exchange of commodities at equal values in Capital Volume I contradicts the conclusion of the formation of prices of production and a general rate of profit laid out in Volume III.

Within Marxist economics, there has been a tedious accumulation of literature attempting to show that there is no logical contradiction. This project is closely tied and is almost reducible to giving various interpretations of Marxist theories. One attempts to find the logically consistent interpretation in order to come up with a testable labor theory of value. We have all sorts of competing interpretations intended to solve the transformation problem: the simultaneist versus temporal, single-system versus dual, commodity-form, etc.

How do we go about challenging this claim of self-contradiction? How can we stop the endless proliferation of interpretations in order to construct a testable and well-supported theory?

Using the Philosophy of Science to Approach the Problem

The critique of the LTV took on a deeper dimension with the philosophy of science. Pre-1968, the only living philosophy of science was logical positivism. Joan Robinson, a student of John Maynard Keynes, himself a student of the great logical positivist Bertrand Russell, was one of the first to make forcible epistemological arguments against the LTV.

According to the neo-positivists, science is in the business of coming up with theories, bodies of declarative sentences organized into a deductive-system. Some of these statements are couched in theoretical terms, while others are couched in observational terms. Each statement is true if and only if it is verifiable, i.e. observable. If it is not verifiable, then the statement is neither true nor false, but simply meaningless. It is a piece of metaphysics that should be eliminated from consideration.

As theoretical statements are not directly observable, they must be reducible to statements about direct observations. If they are not reducible to such statements, then the theoretical statements and terms are meaningless. Robinson argued that “value” was such a term. It could not be seen on an object. It was not a visible but a “metaphysical” property. Therefore, it was a meaningless term and should be eliminated from the conceptual framework of economics.

With time, the philosophical combined with the logico-mathematical in the line of work represented by Piero Sraffa and Ian Steedman. In fact, the LTV became the prime example of a discarded theory in the history of economics within the academy. The only conclusion worth making is that LTV should be discarded as a piece of anti-scientific ideology, relegated to the museum of pseudoscientific oddities alongside “phlogiston” and “ether.”

Many Marxists began accepting these ‘arguments’ around the time that the socialist movement was losing confidence and power. Neoliberalism had its effect on the economic academy and on those persons confined to a position of internal resistance. As part and parcel of the assault of capital and the defeat of labor, these Marxist intellectuals and economists were unprepared to defend the most basic propositions of Marxian political economy.

Counter-Attack and Defense of the Labor Theory of Value

The basic point, however, is that logical argumentation is not how scientific theories are ultimately accepted or rejected. A theory is accepted or rejected only if it is tested and supported by the facts. No economist tried to reject the LTV by testing and showing that it was not supported by the facts. Therefore, all talk of the LTV being “disproven” is moot. All these idiots have done is shown how particular mathematical formalisms are inconsistent, i.e. entail contradictions. That says nothing about the real relation between prices and labor.

In the middle of this one-sided ideological massacre, two mathematicians named Farjoun and Machover published a book called “Laws of Chaos” (LOC). LOC is one of the most important and overlooked works of Marxism ever written. The philosophical, epistemological, and scientific implications of this book are revolutionary.

Farjoun and Machover transform the whole of the Marxist research program in political economy. The authors believe that all economics, including Marxian, flounder on a false assumption: that the economy tends towards a stationary state of equilibrium. In this deterministic picture of the capitalist economy, economic categories such as price and profit gravitate around this one point of equilibrium, so e.g. there is an economy-wide rate of profit.

Farjoun and Machover begin by rejecting the deterministic picture of capitalism that is tacitly assumed in such a theory. Logic and evidence exclude the possibility of such a system. In rejecting such a picture, they adopt a more realistic understanding of capitalism, but also of scientific practice and theory.

In a brilliant instance of scientific modeling, Farjoun and Machover recognize that physics has already produced successful theories about anarchic and disorganized systems, and they use these theories to analyze the capitalist economy. They argue the capitalist economy is anarchic and disorganized, as millions of producers and workers, millions of buyers and sellers interact such that at the macro-level the effect is uncoordinated, and as such resembles a container of millions of gas-particles colliding, acting against one another, and moving in unpredictable ways.

Statistical mechanics is precisely the science that studies such anarchic and disorganized physical systems, and it does so in irreducibly non-deterministic and probabilistic terms.

Physics tells us that such systems have ‘many degrees of freedom,’ and that the movement of each individual particle is ‘random.’ We cannot predict with certainty the micro-properties of a specific molecule. However, and this is extremely important, we can make statistical statements about aggregates of molecules. In like manner, we can make statistical statements about the aggregate economy, distributions of prices and profit-rates, but not about one profit rate. There is no “economy-wide profit rate” but a dynamic distribution of profit rates in which, at the granular level, individual profit-rates (firms) constantly change and switch positions.

Now whatever science is, it is certainly in the business of describing and explaining causal mechanisms. In the process of understanding, prediction is used as a means of testing, keeping, or discarding a theory.

However, when we use a theory to make a prediction we should always specify beforehand the set of relevant competitors. If the theories make the same predictions it is difficult to determine which to choose. If two competing theories make different predictions, then by observation or experiment we can eliminate one. This scientific method allows us to discard those theories that we know to be false while keeping those theories that do best faced with the evidence.

Neo-classical economics’s predictions concerning prices and labor-content are falsified. Orthodox economics predicts that there will be no connection between labor-to-capital ratios and profit. Farjoun and Machover’s probabilistic theory of labor-content, continuing the classical program of Smith, Ricardo, and Marx, predicts that industries with a high labor-to-capital ratio will be more profitable than those with a lower ratio. The prediction checks out as a statistical generalization. The statistical generalization falsifies the orthodox claim and provides support for the claim that the price of a commodity varies proportionally to its labor-content i.e. the labor theory of value.

Since the publication of Farjoun and Machover’s work, there has been a proliferation of literature that supports the LTV (Shaikh, Cockshott and Cottrell and Michealson, Zachariah). Time and again, prices of commodities have varied proportionally with labor-content. As with any statistical law, an individual price might not be exactly proportional with its labor-content, but in aggregate commodity prices cluster tightly around labor-values. For instance, a paper by Cottrell and Cockshott finds that labor-content is an extremely efficient (but biased) predictor.

It would seem that Marxist political economy is the victor unless there is another more likely and better-supported theory on price.

Probabilistic Political Economy and Its Philosophical Meaning

There is a deeper point to take out of all this, a deeper point about science and the world we live in. Quantum physics was a revolution that unsettled previous conceptions on the universe. This unsettling led to some bizarre doubts: some philosophers went to the extreme of claiming that quantum physics ‘eliminated matter,’ made reality a function of ‘subjective perception.’ Those who took a more cautious stance towards the quantum revolution drew better lessons.

Quantum physics weakened the Enlightenment perspective of the world as a well-oiled machine, and with it the belief of science as the production of a universal explanation that is a total prediction of every event in time.

Likewise, Farjoun and Machover have built a theory that does not presuppose capitalism to be a machine. Instead, capitalism is quasi-determined (in production) while also ruled by unpredictable changes and circumstances (in exchange). Science is a project of understanding, describing, explaining, and questioning the determined and chancy process of nature, and prediction enters in as one kind of epistemic act of many.

Take the typical critiques of Marxism as a failed scientific research program that rested on a prediction that did not check out. There were perhaps some Marxists who had an extremely deterministic picture of history. Whether it was the productive forces or the working-class, some irreversible process in capitalism would necessarily lead to socialism. But to be a Marxist is to understand that our material, like our social world, is no machine with a central brain; it is both determined and subject to unpredictable changes and circumstances, and like anything, there is no guarantee of socialism. Marxists must always live with this chanciness, uncertainty.

Awful though it is, this is the way Marx saw history: No guaranteed finalities. Just the fight.

Reading List

I know that going through different academic disciplines to parse out the good from the bad takes a lot of time, so I have provided a reading list of my inspirations in writing this piece if you would like to learn more and engage with the problems.

Philosophy of Science

Summary :

Okasha, Samir. Philosophy of Science: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2016. An excellent and easy-to-read introduction on the field of the philosophy of science. Particularly strong in describing verificationism and neo-positivism, charting the neo-positivist versus anti-positivist debate on the character of science and theory.

Harre, R. (1972). The Philosophies of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Older edition, but gives a great summary of the competing philosophical positions on the character and structure theory and science e.g. instrumentalism, conventionalism, realism.

Positivism:

Carnap, R. (2012). Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Dover Publications. One of the first text to introduce the positivist philosophy of science with its concomitant analysis of theory, description, explanation, the place of physics and the distinction between observation and theory.

Hempel, C. (1965). Aspects of Scientific Explanation and Other Essays in the Philosophy of Science. New York: Free Press. The classical statement of neo-positivism in philosophy of science. A pivotal work and guide for many years on theory, description, explanation, and prediction, and on the difference between observation and theory. Also, an interesting critical essay on “functional explanation” relevant to Marxism.

Falsificationism:

Popper, K. (2002). Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge Classics. Written in 1962, this was Karl Popper’s most popular work. It was a response to the neo-positivists and an attempt to overcome various paradoxes in the research program by developing a new conception of scientific growth and justification. Scientific growth does not proceed by testing the true, but coming up with theories, deducing observational consequences, and eliminating the false. This philosophy was known as falsificationism.

Lakatos, I. (1978). The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lakatos was actually a communist in the Hungarian Communist Party before he moved to London to study with Karl Popper. This is a book of essays, and the most famous essay carries the same title as the book. In it, he charts a more ‘nuanced’ version of falsificationism, ‘naïve’ versus ‘sophisticated’ falsificationism. Needless to say, Popper did not like this distinction and did not appreciate Lakatos’s close friendship to Paul Feyerabend.

Anti-Positivists:

Kuhn, T. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Thomas Kuhn, a physicist by training, wrote this famous work in 1962. It was an attack on the neo-positivist philosophy and its conception of scientific change. Famous for introducing the now abused term “paradigm shift” into the study of theories.

Feyerabend, P. (2010). Against Method. London: Verso. Feyerabend moved to England to study with Wittgenstein at Cambridge. However, Wittgenstein died and so he went to study with Karl Popper the London School of Economics. He became a fierce critic of every philosophy of science and adopted a position known as ‘theoretical Dadaism’ or ‘theoretical anarchism.’ Essentially, in the war of science, any means of victory are permissible, there are no rules. Marxists may like that he tries to bring Lenin into his philosophy as an inspiration to think of science in strategic terms, i.e. as a conflict.

Realists:

Harre, R. (1972). The Principles of Scientific Thinking .London: Macmillan. An extremely interesting work that criticizes the neo-positivists and builds a new philosophy of science. The position is essentially that science is not in the business of describing and explaining observations, but the causal structure and mechanisms that produce observable events in both regular and irregular ways. The main product of science is a deductive theory, but a model of the causal structure and mechanisms ‘behind’ our world.

Hacking, I. (2010). Representing and Intervening. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stakes a similar position against neo-positivism. However, approaches the Marxist understanding of science not just as a process of representing (theory) but intervening in our world (practice). In short, the criterion for the murky word ‘real’ is if something has causal effects, and if it affects us, then it is real.

Marxism

Lesser-Known Marxist Philosophy:

Gasper, P. (1998). Marxism and Science. An introduction to Marxist philosophy of science that stakes out the major claims and goes through the history of the tradition. Also, gives a reading list of works of science.

Sheehan, Helena. Marxism and the Philosophy of Science: A Critical History: The First Hundred Years. Verso, 2017. An excellent book that traces the history of the engagement of Marxists with science from Marx and Engels to the “British Scientific Socialists.” Does justice to the specificity and achievements of the Marxist understanding of science.

Ruben, David-Hillel. Marxism and Materialism. Harvester Press, 1979. A good synthesis of the Marxist and analytic traditions of philosophy.

Wright, Erik Olin, et al. Reconstructing Marxism: Essays on Explanation and the Theory of History. Verso, 1992. An excellent work in the analytic tradition which is actually the best-produced criticism of GA Cohen’s technological determinism. Pursues powerful analogies between evolutionary theory and historical materialism, and defines a class of social theory which attempts to study irreversible processes. Also is one of the first works to systematically interrogate the nature of explanation in Marxism.

Introduction to Marxist economics:

Mandel, Ernest. An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory. Pathfinder, 2006. This work was actually published in 1974 by Ernest Mandel, a Trotskyist leader, economist, and writer. Before judging his political origins, I have found that this work is a fun introduction for the novice.

Sweezy, Paul M. The Theory of Capitalist Development: Principles of Marxian Political Economy. Monthly Review Press, 1970. Written by the famous Harvard Marxist economist and one of the founders of Monthly Review. A terrific analytic introduction to the basics of Marxist political economy. However, nearly everything said about the transformation problem is worthless and should be avoided.

Advanced Texts:

Farjoun, Emmanuel, and Moshé Machover. Laws Of Chaos: A Probabilistic Approach to Political Economy. Verso ed., 1983. I spoke of this monumental work above.

Shaikh, Anwar. Capitalism: Competition, Conflict, Crises. Oxford University Press, 2018. This massive work is, in my opinion, the greatest achievement theoretical and empirical achievement of Marxist economics since Capital. The goal of the work is to systematically re-found the whole of economics on the inspiration of the classical tradition of Smith, Ricardo, and Marx. Rather than obsessing over ‘micro-foundations,’ ‘perfect competition,’ and ‘general equilibrium,’ Shaikh demonstrates how a few principles of political economy can serve as the basis for the ‘turbulent dynamism’ of capitalism.

Studies of the LTV :

Gillman, Joseph M. The Falling Rate of Profit; Marx’s Law and Its Significance to Twentieth-Century Capitalism. Cameron Associates, 1958. The first major attempt by someone to test the labor theory of value and the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

Cockshott, Paul & Cottrell, Allin & Michaelson, Greg. (1993). Testing Labour Value Theory with input/output tables.

Zachariah, Dave. “Testing the Labor Theory of Value in Sweden” (2004).