Communists must take a leading role in rebuilding the labor movement and fighting against anti-union laws like Taft-Hartley, argues Anton Johannsen.

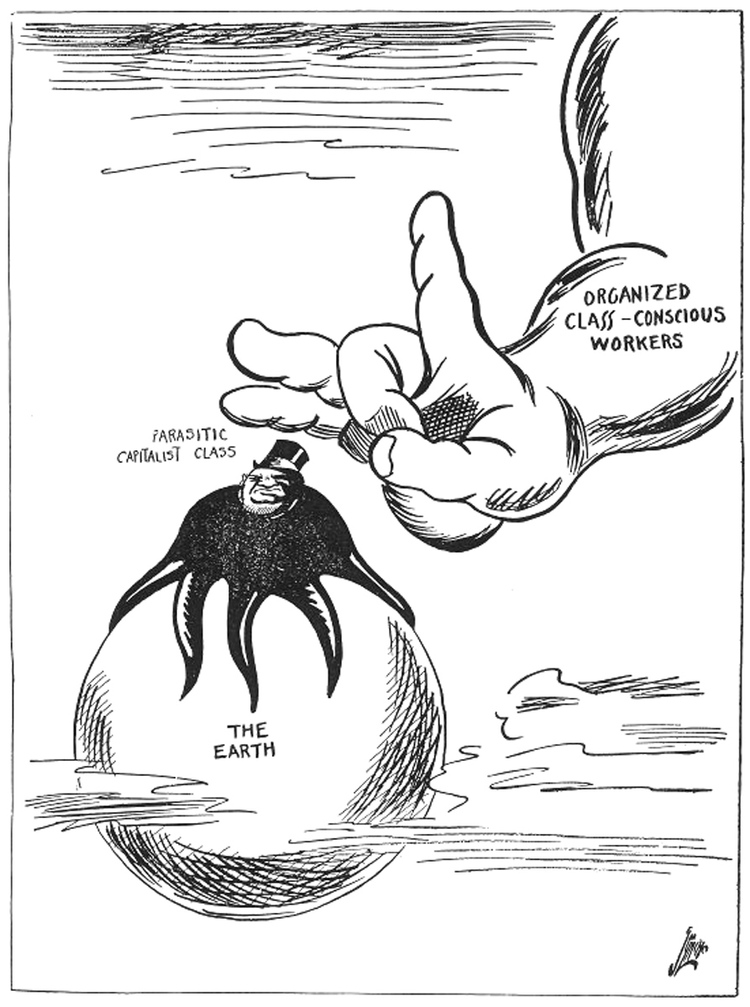

There is a continuum of left positions on unions. Syndicalism argues for very particular forms of unions as the central revolutionary organizational bodies, and often views existing unions as corrupt and useless. Trotskyists and most Stalinists see bureaucratic unions as in need of a leadership change; communists must lead them, and in turn the unions must be subordinated to the party. Anarchists, like syndicalists, often support unions of a particular anti-statist bent. With the exception of Bordigists, left communists see little to nothing of use in unions or involvement in union work. There are partial truths that all tendencies recognize across the board, yet none of these views are sufficient. In this piece, I will try to briefly outline an argument for why communists need to develop a unique strategy to help build unions and that communists must fight to strengthen workers’ rights by repealing Taft-Hartley’s provisions which treat U.S. workers like indentured servants.

Unions are on the front lines of the class struggle for workers under capitalism. By “union” here I mean some form of organization for defense and attack at work. Note that this is an abstract definition, i.e. a simple model or category. From this abstract model, we can then bring in factors of the world or the particular form a union takes in order to concretize the discussion and clarify problems with unions.

For example, unions charge members’ dues and use the money to pay staff and officers to carry out their work. We can concretize this further. Most unions pay executive national/international positions relatively fat salaries. In most unions, these positions are monopolized by bureaucrats, a form of legal corruption, and in some, outright illegal corruption.

This is beneficial to the bourgeoisie and they prefer it this way. In the 1990s, members of the Teamsters voted out the union’s president, Jimmy Hoffa Jr., the notoriously employer-friendly son of the mobbed-up union boss, Hoffa Sr. Ron Carey, a reform candidate endorsed by the Teamsters for a Democratic Union, won on a platform of slashing bloated union-executive compensation and waste, democratizing the union, and supporting the drive to strike against UPS in order to bring part-timers into full-time positions, among other demands. In 1997, with Carey at the helm, 185,000 Teamsters went out on strike for 3 weeks after years of preparation through a rank-and-file organizing drive among members. The union brought UPS to its knees, and they were not happy. Carey himself recalls the negotiating meeting where UPS accede to the union’s demands:

“I recall an incident which occurred in the last hours of those strike negotiations which illustrates the level of animosity the corporate community felt for me: one of the negotiators for UPS said, in the presence of then-Secretary of Labor Alexis Herman, “Okay Carey, we agree on the union’s outstanding issues,” and he proceeded to leave the conference room. As he was leaving, he leaned over the conference table and said to me, “You’re dead, Carey, and you will pay for this, you s.o.b.” I looked at Ms. Herman, and asked, “Did you hear that?” She responded, “I heard nothing.”1

Over the next four years, Hoffa Jr., UPS, the corporate media, and House Republicans led a smear campaign against Carey that saw him barred from running for re-election and eventually banned from the Teamsters for life. They alleged that Carey had knowledge of a scam worked out by his campaign consultant, Jere Nash, to use union money to fund the election campaign, a significant chunk of which was kicked back to this consultant’s business,

“”Nash’s testimony also revealed that he may have been neck-deep in a shady conflict of interest. In 1996 he received $128,000 from Martin Davis’s consulting firm, which was the largest vendor for the Carey campaign. This pay was ostensibly for six months of part-time work Nash did related to the Clinton-Gore campaign. (Nash’s compensation from the Carey campaign was much less: $2,500 a month.) Nash simultaneously was managing the Carey campaign and employed by its biggest creditor. The swaps occurred when Nash and Davis were looking for money to pay for a $700,000 direct-mail push for the Carey campaign–a direct-mail effort to be handled by Davis and one that would result in large profits for his firm. With Davis his main income source, Nash, then, may have had a financial incentive to go along with Davis’s swap scheme and not inform Carey of it. And as Carey’s attorneys noted, Nash, who is cooperating with the U.S. Attorney, might be testifying against Carey to win a reduction in sentence.”2

In 2001, Carey was acquitted by a jury of any knowledge of the scams. By that time, Hoffa Jr. had won a re-election campaign for President of the Teamsters. The business community was ecstatic, with the trade magazine Transport World writing in 2000:

‘United Parcel Service, the nation’s largest transportation company, feels that it has taken part in one of the great trades of all time in labor: James P. ‘Jimmy‘ Hoffa for Ron Carey as president of the Teamsters union.’3

To be clear, the bourgeoisie rule through legal corruption, and delight at the illegal corruption of workers’ organizations. This helps them maintain hegemony over these organizations or crack down on them through the state. By legal corruption, I mean access and retention of office by means of money. This is legalized through restrictive pressures put on political campaigns by money: it’s much easier for the wealthy to reach a broad audience. As well, access to public relations firms and resources to carry out an election campaign, even within a union, require a lot of resources.

Jere Nash, Carey’s consultant, was a Democratic Party insider and campaign strategist. The set-up to Carey’s downfall was also the decades of corruption fostered in the Teamsters by Hoffa Sr., which led to the standing Federal monitoring of Teamster elections through an Independent Review Board, the representatives of which also played a role in bringing Hoffa Jr. back to power.

The key here is that the anti-democratic features of the Teamsters, their corruption, led to the political intervention of the state, not in the direction of ending corruption, but ensuring the corrupt leaders retained control.

The other features of bureaucratic unions are liberal and anti-republican organizational rules such as meaningless referendums, powerful executive bodies, and non-representational forms of organization. Strong executives in unions and a lack of membership vote (let alone membership control over bargaining and negotiations) are preferable to the bosses because they make it easier to wring a favorable solution out of the union by buying off union bureaucrats or taking advantage of divisions between the leadership and the membership to compel agreement.

This dynamic toward corruption is often cited as a reason to oppose the “bureaucratic unions” by anarcho-syndicalists and for the left communists, at times a reason to abstain, forsaking any kind of struggle for influence and leadership in the unions. But there is another logical step. Left communists argue that unions are naturally prone to becoming corrupt in this way by virtue of their form, no matter the ideology. On the other hand, anarcho-syndicalists point out that unions are like any social organization: they reflect the choices of members and leaders in their form and their activity. Thus, unions must be anarcho-syndicalist in nature in order to succeed. So far, so good. The problem with this? The reduction of virtually every anarcho-syndicalist union in the world to national membership levels of less than 10,000 across the globe. For anarcho-syndicalists, especially in the U.S., the form of a union is in equal measure to the strategic choices of the union participants in determining the more or less effective or revolutionary aspects of the union.

Direct Unionism, a view of union organizing promoted by a tendency in the American and Canadian sections of the IWW, proposes the following as an alternative to “bureaucratic unionism”:

“. . . that instead of focusing on contracts, workplace elections, or legal procedures, IWW members should strive to build networks of militants in whatever industry they are employed. These militants will then agitate amongst their co-workers and lead direct actions over specific grievances in their own workplaces. The goal of such actions will not be union recognition from a single boss. Instead, the goal of the actions is to build up leadership and consciousness amongst other workers. Once a ‘critical mass’ of workers have experience with, and an understanding of, direct action the focus will be on large scale industrial actions that address issues of wages and conditions across entire regions or even whole countries. It will be from this base of power that the IWW will establish itself as a legitimate workers’ organization.”

The Direct Unionists want to build up networks of union activists, essentially. In practice, this is little different from the Labor Notes strategy. The following argument is not that this strategy is in error, just that it is incomplete. How then would the Direct Unionists proceed?

“When organizing without contracts—as direct unionist believe we should be—it is of great importance the IWW is (1) very strategic and tactical in our organizing and (2) honest with ourselves about how much power we can effectively exert in any workplace or industry.”4

The record of the I.W.W. over the past 20 or so years has shown that regardless of how well committee organizers performed according to item 1 above, with respect to item number 2 the reality is that lasting power was never really built.

Partly this must derive from their illusion that there could be a linear growth in the number of committees in the “network” that would work together without some organizational glue to coordinate and facilitate this increasing scale. What Direct Unionism does, in fact, is ideologize a component of many other types of organizing pursued in industries and areas difficult for unions to get a foothold in. This is often called “minority unionism” because the committee, no matter how plugged-in and representative of the workforce, is in the position of not being recognized by the company or the state as the representative agent of the workers.5

Nevertheless, the Direct unionist attempt to deal concretely with the challenges faced by organizers, given the slate of anti-union policy in the U.S., is admirable. But the naiveté of trying to build an industry-wide strike via ad hoc committee-building without any plan of centralization from the beginning reveals an underlying decentralist-anarchist ideology, whether explicitly held by the authors or not. Again, this is made clear by the persistent failure of what end up being isolated campaigns of volunteer committees associated with the IWW in various cities.

The other component to the Direct Unionist line is anti-contractualism. This rightly identifies the pernicious way that most contract provisions which employers are able to get into contracts are contrary to the interests of the workers and that the particular strategy of unions relying on contracts works to demobilize the membership in favor of emphasizing the role of thestaff and officers of a union. The problem with anti-contractualism is that it turns this criticism of particular strategies utilized by unions under current conditions into a dogmatic opposition to contracts that holds back effective organizing that can win long-term power on the shop floor. The very existence of a contract results in the development of a staff corps in the union, marshaled by an entrenched officialdom to rotate throughout the country, servicing bargaining units as their contracts come to expire, and leaving as soon as they are negotiated.

Instead, contracts should be seen for what they are: a measure of strength. The provisions of a contract illustrate the power of the workers to compel an employer to agree to the given provisions. Ultimately, a contract is a piece of paper with rules that must be enforced. The problem to which the Direct Unionists ought to respond is that of the balance of power between members and officials, to the extent that the officialdom and staff enforce poor contracts against members. The other side to this is the role the state plays in limiting the actions and types of demands unions may make, as well as in regulating their internal structure.

Direct Unionists, members of the IWW that they are, are very quick to point out the importance of membership-involvement, democracy, and hold a general anti-staff position. But from here we run into a problem in the question of concrete form. To make a comparison, the UAW (United Auto Workers) and IWW both have general conventions of elected delegates as the main decision making body, with executive boards making decisions in the interim. The UAW has a presidential office, which is an anti-republican office, so that’s one notch against them. The point is that every aspect of ‘form’ betrays a particular interpretation of the world, the structure of society, who can or ought to be able to make what decisions, and so on. Ultimately, the form gives way to the politics. The UAW has a particular form for the same reason they have lengthy provisions about collective bargaining: they have a root theory about how best to defend and help the working class and that theory is at odds with communism.

So, we have an organizational form on the one hand, and politics on the other. The organization is the means to accomplish the ends you seek, and the political ends that liberal union bureaucrats seek are collective bargaining, contracts that track in new members, land nice lump-sum payouts from profit sharing, and the like. At a minimum, through the AFL-CIO, the idea runs that collective bargaining is the best way to defend and attack for the working class. The classic line from the IWW or some leftists is that the bureaucratic unions are just a means for the bureaucrats to make money, and that the best method is committee-driven direct action; strikes and street protests are what show the workers’ true power. This approach bends the stick too far.

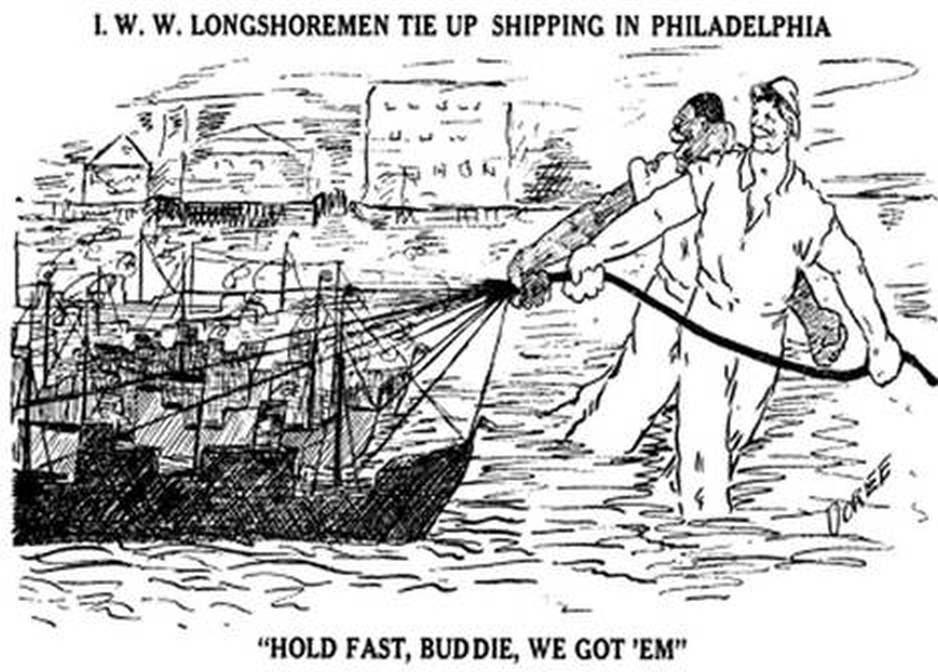

After all, isn’t collective bargaining all that unions do anyway? Even the Local 8 longshore workers in the IWW in the 1910s were engaged in a type of collective bargaining. They made agreements with the employers, independent of whether or not these were drawn up on paper or arbitrated by a state agency. What mattered was that every member of the local was educated about the agreement and ready at a moment’s notice to enforce it through industrial action.

The ideology of the bureaucrats is a reformism that collapses toward liberalism. It isn’t simply a question of the existence of the bureaucrats, but the nature of their grip on the organization and the ideas they offer to the members and public to justify this arrangement. These ideas are political positions of the bureaucrats.

The dominant ideology of the labor bureaucracy in the United States has been a form of liberal, as opposed to republican, democracy. These political positions matter because they undergird the organizational forms and strategies adopted by union leaders, distributed among members and new recruits, and lay the foundation for close links between labor and the Democratic Party. But why has this ideology persisted through generations? One interpretation is this: bureaucrats in capitalist society in general are prone to liberalism in the philosophical sense, that is, their fundamental political commitment will be to discrete individual rights, with property rights at the center, rather than democracy and equality. This is because bureaucracy is a form of private property in skillset or office. Of course, most U.S. unions are still more ‘democratic’ than the U.S. government. This is partly because they have to be, in order to mobilize enough workers to strike at least for initial recognition, but also because of the ideology of the core organizers and members. So the particular form of organization is tempered and guided by the political outlook of those who found, organize, and accompany its development. To demonstrate this point, we can briefly look at the respective constitutional preambles of the UAW and the IWW. Though they have some similarities in governing form (and many divergences) their preambles couldn’t be more different. Let us first look at the preamble of the UAW:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident; expressive of the ideals and hopes of the workers who come under the jurisdiction of this INTERNATIONAL UNION, UNITED AUTOMOBILE, AEROSPACE AND AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENT WORKERS OF AMERICA (UAW): “that all men and women are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men and women, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Within the orderly processes of such government lies the hope of the worker in advancing society toward the ultimate goal of social and economic justice.

The precepts of democracy require that workers through their union participate meaningfully in making decisions affecting their welfare and that of the communities in which they live.

Managerial decisions have far-reaching impact upon the quality of life enjoyed by the workers, the family, and the community. Management must recognize that it has basic responsibilities to advance the welfare of the workers and the whole society and not alone to the stockholders. It is essential, therefore, that the concerns of workers and of society be taken into account when basic managerial decisions are made.”

Note that while the UAW asserts the ‘rights of workers’ as individuals in a democracy to have their voices heard, they don’t deny the right of management to manage, or the right of the idle rich to exploit. This is reflective of a liberal-democratic outlook, amenable to workplace reconciliation and democracy through collective bargaining. Note too that the material basis for the labor bureaucracy is this regime of collective bargaining. Their salaries are based on their success in this field.

On the other hand, the IWW’s preamble asserts that class struggle is the governing mode of the worker-capitalist relation:

“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth.

…It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.”

The world outlook of the IWW argues that class struggle shapes the relationship between worker and employer and that this will be the case until the workers get organized and overthrow the capitalist system of governing society. Unions play the role of defending the day-to-day needs of the class, educating workers about the class struggle, and drilling them into fighting shape.

The point here is that there is a limit to the ‘structuralist’ critique of form. At a certain point, the question becomes what the political commitments of those advocating the particular form are, and what political commitments are implied and accomplished through an organizational form. This needs to be viewed with respect to particular classes in society. Petit-bourgeois professionals and bureaucrats are perfectly happy with an organization investing significant powers in salaried officials and staff. Their role as lawyers, managers and the like endears them to the ‘noble’ applications of their skills in helping out the little guy. This is where the anarchist critique of the bureaucracy has a truth: the position of the bureaucrats does incline them to act differently.

However, this is true for the bureaucrats as a class. The form this self-interest takes hold ideologically or politically is through reformism. Anarchists say that reformism creates bureaucrats. While this true in the sense that particular reforms may create funding for more bureaucrats, it elides the origin of the given reform in the efforts by particular forms of bureaucracy organic to capitalism: the lawyer, the manager, the organization official, and so on. The development of reformism as an ideology is a cyclical process. The bureaucracy requires justification, both for the bureaucrat’s own conscience, and because the bureaucrat must get some support in wider democratic society, especially among the workers.

The flip side of this is that some bureaucracy is necessary as a result of the uneven development of capitalism. That is, given the social division of labor based on property relations, bureaucrats do often possess necessary skills for the growth and survival of the organizations they serve in. The dilemma then is one of whether or not an organization is governed by or governed in the interests of bureaucrats.

Unfortunately, the IWW is also reliant on Robert’s Rules of Order, as are most bureaucratic unions. While parliamentary procedure is important, it can be a tool to monopolize discrete knowledge of procedure and rules for the benefit of bureaucrats to maneuver and control the process. This can be seen in both the UAW and the IWW. Anyone who has been to an IWW convention, or has paid attention to the internal controversies in the organization, can attest to the fact that it is often the case that for a democratic decision to be taken, it has to overcome technical machinations of process. On the other hand, when faced with a seemingly obscure set of unfamiliar rules, the membership response is to simply pressure the parties involved or move the debate away from substantive disagreements and toward interpersonal conflict. The IWW lurches from one political-crisis-as-personal-dispute to the next. Effectively, by adhering haphazardly to some fundamental principles of bourgeois law, the IWW has crafted a situation where every member must be a bureaucrat in order to participate. Rather than abolish bureaucracy, it has abolished any other role for members.

New members elected to leadership positions in the IWW often find themselves in the middle of a handful of formally and informally organized cliques in the union with overlapping members based on political positions. This is to be expected in any large organization, but the goal of the structure of an organization then should be to overcome the dynamic that this fosters, frustrating any resolution of political disagreements to the effect of frustrating effective growth and successful execution of the organization’s program. Instead, the mechanisms of the organization should draw out and clarify political distinctions in order for the membership to become openly apprised of them and to select at congresses or conventions the positions they support.

This is not to let officers off the hook. As leftists tend to point out, there are indeed problems with the leadership of unions. This leadership is exceedingly liberal-democratic in their outlook, which leads to definite problems with respect to organizational form and strategy. As anarcho-syndicalists often point out, business unions invest too much in PR campaigns, officer salaries, and staff-driven symbolic stunts. And as some left communists argue, the tendency toward the development of and coup by bureaucracy is persistent in capitalist society, both in parties and in unions.

But our response to these problems shouldn’t be abstention from unions as a principle or the simplistic alternative of a change to a structureless organization. Instead, we should fight for changes in the governing structures and principles of unions. That means putting the maximum program of socialism in the constitution and making structural changes that allow for transparency and democracy, as well as preparing workers to govern as a class.

A central aim of communists in unions, then, is to build working class power on the shop floor. Workers without a union are barely citizens, as a result of their inability to enforce any rules in their favor at work. Mere inputs for business, workers are disposable, replaceable, and reminded of it daily. The employers exercise a dictatorship over their employees. Workers are completely at their mercy. The union offers an alternative. It offers a democratic formalization of the workers’ own authority. Organized workers are prepared to act in unison. They’re educated and aware of their rights on the job as a result of the work done by the union. They can stand and look their exploiters in the eye as equals, not in terms of bourgeois law, but in terms of power. They can begin to assert themselves as the inheritors of the fight for human emancipation.

Democratic, member-led bargaining has a history of wrenching contracts from employers that got better wages, better conditions, and restricted the grievance procedure to a short process, or, better yet, enabled workers to strike or take action to resolve grievances rather than do so through arbitration. Judith Steppan-Norris and Maurice Zeitlin have shown this in their work on left-led unions during and after WWII and the nature of their contracts and constitutional provisions. The authors write, with regard to “pro-labor” contract provisions:

“The crucial finding is that the comparative odds of the Communist camp’s local contracts being prolabor, as opposed to those in the anti-Communist camp, were consistently much higher on each provision, as follows: The comparative odds that the contracts did not cede management prerogatives were 4 to 1 in favor of the Communist camp; that they did not have a total strike prohibition, 7 to 1; that they were short-term, 4.6 to 1; that they had a tradeoff, 11 to 1; that a steward had to be present at a grievance’s first step, 11 to 1; that the grievance procedure had no more than three steps, 3 to 1; and that each step had a time limit, 2 to 1.” 6

That rank-and-file- and socialist-led unions are more effective is also demonstrated by the aforementioned Local 8 of the Marine Transport Workers’ Union in the I.W.W.’s past. They were able to wrench concessions from their employer and enforce workplace conditions through direct action. If the employer tried to bring in a work gang of non-union members, the work delegates would ensure that the workers immediately ceased work and walked off the job.7 Communists must work to break the reliance of workers on their employers and reorient them to the institutional forms of union self-government: the shopfloor committee, the Industrial Union Local, and the International Union. This means employing the known committee-building tactics, promulgated by the IWW Education committee and groups like Labor Notes, in the context of an explicitly Socialist effort to rebuild organized labor, across the country. Workers without a union rely on the mercy of their employers. They are subjected to an undue and illegitimate authority, forced to produce profit for shareholders and lavishly wealthy corporate executives in order to get crumbs with which to get by. The only way to fight back is to build up the democratic self-reliance of the working class into fighting unions where workers can make collective decisions to wage class war effectively.

Democratic organizing gets concrete results. Union workers are involved not just in voting for a union that will bargain on their behalf, but in fighting for their own demands through group effort, and will not soon forget the power that they build, nor ignore the broader political opportunity to use such power. Witness the West Virginia teachers’ strike that violated the law successfully, not just for narrow demands for teachers, but for demands that would benefit teachers and the public. Union organizing prepares the working class to take part in politics, at the granular level. As Eugene Debs once argued:

“Voting for socialism is not socialism any more than a menu is a meal. Socialism must be organized, drilled, equipped and the place to begin is in the industries where the workers are employed. Their economic power has got to be developed through efficient organization, or their political power, even if it could be developed, would but react upon them, thwart their plans, blast their hopes, and all but destroy them.”8

For these reasons, union organization raises the dignity and education of the workers themselves which opens up the possibility of workers becoming a conscious and active political constituency, fighting for their own interests. Rather than dependent wage workers, union workers build independence by organizing to fight the employers at work. They force the boss to treat them with dignity and exert equal power in that relationship.

Building this alternative democratic authority calls forth all the intense political questions we face under capitalism. The workers’ chains are money, and workers spend most of their living hours for it and end up losing it through high prices, rents, and loan scams, all the while facing disenfranchisement through corruption and bureaucracy. As the bosses, challenged by workers, call on the state to enforce their interests to the exclusion of the workers, they will be forced to ask: who does the state serve? Who ought it serve? And how do we break these chains? Bureaucratic unions often have to deal with these political questions even as their power weakens. But they retreat into the realm of lobbying bourgeois politicians in ways that are often extremely ineffective.

In stark contrast to this, communists must pose a two-pronged strategy. First, there must be a commitment to organizing workers based on democratic principles of membership, sovereignty, and transparency. This entails organizing the working class to use direct action for enforcement of every demand and contract provision as well as a bargaining strategy aiming for zero-recognition of management rights and no-strike clauses, and lengthy grievance procedures as far as possible. Second, communists must augment this work with political work mobilizing votes to repeal Taft-Hartley. Taft-Hartley is a federal law which requires advanced notice for strike action wherever workers hold a contract with an employer. This severely limits workers’ abilities to enforce their contracts through direct action and attain the robust and fighting labor movement we aim for, outlined above.

Prioritizing the repeal of Taft-Hartley means making it a litmus test for any candidate for office. This further requires that there be a broad enough base of support in elections, but ultimately in the streets and at work, as the French Yellow Jackets and West Virginia teachers have shown. Politicians are important to help spread our ideas and eventually pass reforms, but street protests and industrial actions are key to winning and keeping them. This is why the need to begin organizing now is so important. Communists must combine the day-to-day fight to rebuild the labor movement with a national political campaign to repeal Taft-Hartley. In turn, Taft-Hartley’s repeal will bolster union organizing and help strengthen the fight for a communist movement based on democracy.