Gil Schaeffer responds to Chris Maisano’s “The Constitution and the Class Struggle” to clarify the meaning of the “class point of view in Lenin and what it can tell us about the struggle for democracy.

When I first ran across Seth Ackerman’s “Burn the Constitution” back in 2011, I thought: wow, here is some writing with the power and incisiveness of I. F. Stone, Malcolm X, Carl Oglesby. I immediately went to the Jacobin website, expecting to find a radical democratic publication. It turned out to be something much more tentative and diffuse. Alongside Ackerman’s searing indictment of the U. S. political system, there was a mix of articles wrestling with the problems of postmodernism and identity politics in the academy, of the unfulfilled promise of social democracy in Europe, and of what life in a socialist society might look and feel like. Over the next five years, Jacobin stuck to this editorial policy of publishing a wide range of views on the left and its history without feeling any pressing need to define a distinctive ideology and strategy of its own. But that changed with Bernie Sanders’s 2016 campaign for President. Trying to catch up to and influence the hundreds of thousands of young people drawn to the idea of socialism through Sanders’s campaign, Jacobin has since put a great deal of effort into articulating its strategy of a “democratic road to socialism.” I laid out my criticisms of this strategy and the selective use of Karl Kautsky’s writings to justify it in “The Curious Case of the ‘Democratic Road to Socialism’ That Wasn’t There”. The aim of this article is the opposite. Its purpose is to pick out what is positive in Jacobin’s thinking about a democratic road to socialism and carry its logic beyond the scope of that publication.

At the end of “Why Kautsky Was Right (and Why You Should Care)”, after presenting his case for a strategy of winning elections within the “capitalist democracy” of the U. S., Eric Blanc tacks on the qualification that the U. S. actually has an “extremely undemocratic political system.” Blanc doesn’t think that calling the U. S. both democratic and undemocratic at the same time is a problem and patches over this paradox by adding that the strategy of winning elections should also “prompt socialists to focus more on fighting to democratize the political regime.” As examples of how this two-pronged strategy of winning elections and democratizing the political regime at the same time might work, Blanc links to two proposals put forward by Jamal Abed-Rabbo1 and Chris Maisano2, respectively. Because Abed-Rabbo’s piece only focuses on the particular problem of first-past-the-post electoral systems and does not even mention the problem of disproportionate representation in the Senate or the unaccountable power of the Supreme Court, it doesn’t really address the most serious anti-democratic features of the Constitution and can safely be put aside. Maisano’s article, on the other hand, does confront the full scope of the Constitution’s undemocratic structure and therefore merits closer examination.

I’m going to break down Maisano’s article into three parts: its solid political and historical core, its weak tactical and agitational recommendations, and the theoretical question about the relationship between democracy and the class struggle suggested in the title.

Like Ackerman, Maisano lists the many ways in which the Constitution violates the basic democratic principle of one person, one equal vote, but Maisano goes further and places the problem of democracy in a larger historical and international context. Urging the DSA to “develop a national political platform that includes a call for the establishment of a truly democratic republic for the first time in our country’s history,” Maisano emphasizes that the demand for a democratic republic has been at the center of working-class and socialist movements from the start, beginning with the U. S. Workingmen’s Party and the Chartists in the 1820s and ’30s, continuing in the work of Marx and Engels, and finally becoming the primary political demand of pre-WWI European Social Democracy and the U. S. Socialist Party. He ends with the assertion that the democratic republic is “the framework in which the transition from capitalist oligarchy to democratic socialism will eventually be achieved.”

So far, so good. Maisano has outlined the classic Marxist conception of the relationship between winning the battle for democracy and the transition to socialism. The next question is what tactics and forms of political agitation the demand for a democratic republic calls for. Here Maisano abandons any reference to how working-class and socialist movements fought for democracy in the past and shifts to a legalist constitutionally loyal framework, concluding that “Given the egregiously high barriers to calling a constitutional convention or amending the current constitution, a demand for a wholly new constitution would be utopian.” Not surprisingly, this statement triggered criticisms that Maisano was giving up the fight for democracy before it had even begun. Tim Horras in particular zeroed in on this statement as proof that “the reformists turn back before even reaching the limited horizon of bourgeois legality.”3

However, Horras’s criticism of Maisano’s tactical timidity, unfortunately, did not include a reassertion of the political centrality of the goal of a democratic republic. To be sure, Horras agreed with Maisano that the U. S. political system is undemocratic, but for Horras this lack of democracy is just one more reason to begin to prepare immediately for armed insurrection and socialist revolution. Maisano responded that Horras’s insurrectionist strategy would lead only to the left’s political isolation. To avoid isolation, Maisano argued4 that participation in elections should be the primary focus of socialist political activity in “a formal democracy like the U. S.” Now, notice the funny thing that has happened in the course of this back and forth: the demand for a democratic republic has dropped out of the picture. What started out as a promise by Maisano to explore the relationship between the Constitution and the class struggle ended up with Maisano falling back into calling the U.S. a democracy and forgetting about the democratic republic. I think Maisano’s original promise to discuss the relationship between the Constitution and the class struggle is too important to let go.

It is not clear what moved Maisano to take up the subject of the Constitution in the first place and to urge the DSA to include the demand for a democratic republic in its platform. Although Jacobin has continued over the years to publish articles on the Constitution and the history of the working class’s struggle for democracy, its main political and theoretical preoccupation has been the failure of post-WWII European social democratic parties in genuine parliamentary democracies to continue down the road to socialism. The Bread and Roses caucus of the DSA has codified this Eurocentric focus in its “Socialist Politics: A Reading List,” which leans heavily on the work of Miliband and Poulantzas. Maisano raising the problem of the Constitution and the possibility that the U. S. isn’t a democracy at all is definitely an outlier in this theoretical scheme. Obviously, something bugged him about the peculiarity of the U. S. political system and he felt the need to write about it. This willingness to question and expand the received categories of prevailing socialist thinking is the positive element in Jacobin’s strategy of a democratic road to socialism. My aim is to follow Maisano’s turn down the road toward a democratic republic to the end.

Maisano himself stops and then veers off this road. He stops in the first article because he thinks the immediate demand for a democratic constitution would be “utopian” and he veers back onto the electoral road in his reply to Horras, reverting to the fairy tale that the U. S. is a democracy, that its electoral system possesses a controlling legitimacy, and that participation in this system is the main way to constitute the working class as a collective political subject. I’m not going to try to get inside Maisano’s head to figure out why he veered back or to polemicize too strongly against this electoral road. Rather, I’m mainly going to measure Maisano’s political positions against his own references to the history of the struggle for democracy. Let’s start with utopian. Utopian means adhering to an ideal that is not humanly realizable. What does Maisano mean when he says that the demand for a wholly new constitution would be utopian? The working-class movements of the past that Maisano references did not think the demand for democracy was utopian, and a good number of countries now have democratic political systems as a result. Maisano is misusing the word and seems to be saying that the demand for a democratic constitution in the U. S. is not immediately realizable. But no one would dispute that. The issue is what demands are for. They are not just for what is immediately realizable; they can also be analytical, educational, and aspirational. The history of Marxism is largely made up of debates about what demands should be included in a political program and how these demands might best be communicated to workers in the hope they will adopt them as their own. Maisano doesn’t delve very deeply into this history and drops the subject altogether when he switches over to his dispute with Horras.

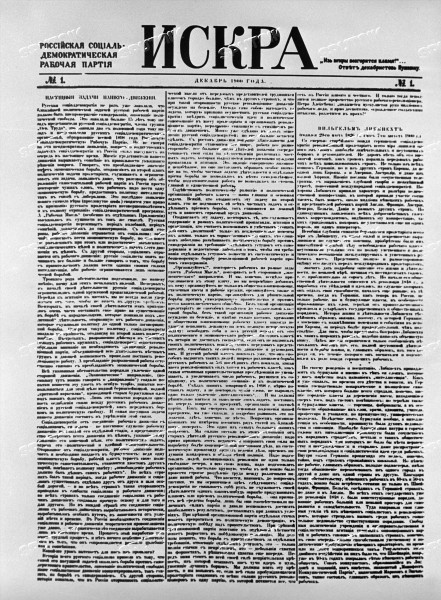

Horras is an easy target, a modern-day reincarnation of one of Lenin’s left-wing communists. Because capitalism is historically obsolete and ultimately can only maintain itself through armed force, Horras thinks the main job of socialists is to pound away at this truth and to get ready militarily for the final showdown. He forgets Lenin’s admonition that what is historically obsolete is not necessarily politically obsolete. Lenin was certainly a believer in Marx’s theory of the state when he launched Iskra, but that newspaper’s purpose was not to repeat Marx’s doctrine of the state over and over again and urge immediate military preparedness but to take mass political sentiment as it existed in order to develop it into a political movement demanding that society’s laws be made by a democratic assembly of the people. Building the consciousness for such a political movement was his main preparation for the ultimate conquest of power. Luxemburg’s approach was the same when German workers rose up to demand suffrage reform in 1910. Horras completely ignores this history of how Marxists went about building mass political movements. Maisano makes a similar criticism of Horras’s stunted conception of mass politics and argues that “Political Action Is Key.” He is right. The question is what kind of political action.

For Maisano, political action is overwhelmingly electoral action. In his reply to Horras he writes, “elections and participation in representative institutions plays a crucial role in constituting classes as collective political subjects. As Carmen Sirianni has argued, parliaments ‘have been the major national forums for representing class-wide political and economic interests of workers… there was no pristine proletarian public prior to parliament, and the working class did not have a prior existence as a national political class.’”5 Really? I have no idea what a “pristine proletarian public” is supposed to be, but I do know that the Chartists and the European workers’ organizations and parties that led mass campaigns for the right to vote already had a sense of themselves as a national political class in order to demand the vote in the first place. And even after they had won the right to vote but were trapped within systems of unequal representation, the leading expressions of national political class consciousness were centered in the literature, protests, demonstrations, and strikes demanding further suffrage reform and complete democracy. Of course, electoral campaigns and parliamentary oratory also played a role in these movements, but the working class’s sense of political legitimacy was invested in the goal of true democratic representation, not in the restricted power and choices of existing unrepresentative parliamentary elections and institutions.

The underlying problem with Maisano’s analysis and with the Jacobin/Bread and Roses political tendency is that they take as their baseline the world of post-WWII European social democracy. There are two reasons why this model is inadequate for understanding the challenges facing the U. S. left. The obvious one is that the U. S. is still a pre-democratic state in which elections are vastly less representative than in European social democracies. The less obvious one concerns the historical and political origins of Europe’s social-democratic institutions themselves. It must be remembered that fascism crushed the European workers’ parties and movements and was only defeated by the Allied armies in WWII. In the western part of Europe, the U. S. then oversaw the construction of parliamentary institutions remarkably more democratic than its own in order to neutralize the appeal of more radical left and Communist political forces; yet these new national governments were enmeshed in a web of super-national Cold War military and economic structures dominated by the U. S., a dominance that continues today. Jacobin talks very little about this difficult history, but it is a decisive factor weighing against their position that contemporary European social-democracy is a useful guide for understanding how our own struggle for democratic political institutions is likely to develop.

In arguing that the DSA should include the demand for a democratic republic in its platform, Maisano linked to the 1912 Platform of the U. S. Socialist Party, which called for the abolition of the Senate and the veto power of the President, the removal of the Supreme Court’s power to abrogate legislation enacted by Congress, the election of the President by popular vote, and the ability to amend the Constitution by a majority of voters in a majority of the states. Where have these demands been for the last one hundred years? Very roughly, WWI and the Bolshevik Revolution not only split socialists into hostile revolutionary and reformist camps, they also gave rise to the entirely new concepts of soviet vs. parliamentary democracy and one-party rule vs. multi-party elections. For Marxist-Leninists, the old goal of a democratic republic was no longer enough and was summarily dismissed as just another form of bourgeois democracy. On the reformist side, liberal capitalist republics like the U. S., no matter how distorted and unrepresentative their political systems, were increasingly referred to as democracies in contrast to the Soviet dictatorship. The reputation of the U. S. was further enhanced by the contrast between the New Deal and fascism. This democracy/dictatorship dichotomy so dominated political thinking over the last century that even democratic-minded comparative historians such as Barrington Moore, Eric Hobsbawm, Perry Anderson, and Michael Mann were not able to break away from classifying the U. S. as a liberal or social democracy. They couldn’t see that we are still in the Age of the Democratic Revolution.

There was a brief revival of democratic language and thinking in the Civil Rights Movement and in the participatory democracy of the New Left, but that gave way by the late 1960s to revolutionary anti-imperialism and Maoism. After twenty years in the doldrums, which included the collapse of the Soviet Union, some new thinking began to emerge in the mid-1990s. On an intellectual level, fundamental critiques of the Constitution’s structure started popping up, beginning with Thomas Geoghegan’s “The Infernal Senate” (1994), followed by Daniel Lazare’s much more comprehensive The Frozen Republic: How the Constitution Is Paralyzing Democracy (1996), Robert Dahl’s How Democratic Is the American Constitution? (2001), and Sanford Levinson’s Our Undemocratic Constitution (2006). Popular dissatisfaction with the political system grew in parallel. The list of offenses is long: the Democratic Party’s failure to reverse conservative policies and pro-corporate economic dogma after twelve years of Republican rule; the Supreme Court’s intervention in the 2000 election; the lies and deception of the Iraq war; the failure, again, of the Democrats to come to grips with the economic and health care crises, this time hiding behind the fig leaf of the filibuster; and then the 2016 election and the absurdity of the Electoral College. The response has been Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, increasing working-class activity, Bernie Sanders, DSA expansion, and the electoral victories of Justice Democrats. Maisano has attempted to pull these historical, intellectual, and political strands together into a coherent ideological and strategic whole. He doesn’t get it right, but he does raise the right question: What is the relationship between democracy and the class struggle?

There is no way to answer this question without first pinning down more specifically what we mean by democracy. Maisano and Jacobin in general wobble back and forth between defining democracy as universal and equal suffrage or just universal suffrage.6 The 1912 Platform of the Socialist Party contained no such ambiguity and neither did the programmes of the socialist parties of the Second International. The most comprehensive analysis of this issue by a Marxist was made by none other than Karl Kautsky in his 1905 essay, “The Republic and Social Democracy in France.”7 In a comment on my last article, Jacob Richter called this essay “State and Revolution before Lenin’s pamphlet, minus overheated polemical language.” This characterization is accurate because the aim of both was to use Marx’s writings on the Paris Commune as the measure of the meaning of democracy and the institutional requirements of a truly democratic republic. The target of Kautsky’s critique was the Third French Republic, which had universal and relatively equal voting for the lower house of its legislature but restricted and indirect voting for its Senate and powerful centralized presidency. Engels had called this system “nothing but the Empire established in 1799 without the Emperor,” and Kautsky’s argument was that social democrats should not take ministerial positions or expect adequate reforms within such a system but should concentrate their agitation and activity on complete democratization. The logic was simple: If the leaders of a bourgeois republic were truly open to meaningful reform, they would remove the electoral barriers preventing reform. Means and ends went together. Without a fully democratic political system, it was a “republican superstition” to expect democratic results. When Maisano and the Jacobin/Bread and Roses group choose only universal suffrage rather than universal and equal suffrage as their standard of democracy, they are falling for this republican superstition.

Left-wing politics follow a predictable pattern in political regimes with universal suffrage but unequal representation. Those who are under the influence of the republican superstition elevate the winning of elections over agitation for full democracy. Then, because little or nothing changes, large sections of the population lose patience with politics-as-usual and rise up in protest. Those willing to pursue electoral victory on the lowest possible political basis then typically react by accusing the protesters of undermining the chances for electoral success. The dispute between Luxemburg and Kautsky in 1910 followed this pattern, as did the confrontation at the 1964 Democratic Party National Convention over the seating of the Mississippi Freedom Democrats, and, in our own recent mini replay of this drama, we have Dustin Guastella in Jacobin condemning militant protest activity and identity politics for endangering his bread and butter electoral strategy (his final rant coincidentally appearing on the same day as George Floyd’s murder).8 Guastella’s remarks may have been unusually crude, but they were still well within Jacobin’s current ideological framework that distinguishes “anti-electoral movementism” from their strategy of “class struggle elections.”9 Of course, this either/or dichotomy is incomplete and misleading because it leaves out Jacobin’s and Maisano’s own historical reminders that the first priority of the class struggle in classical Marxism was the fight for universal and equal suffrage. They seem to forget that in an undemocratic political system there can be such a thing as a movement for electoral democracy.

Just as the meaning of democracy gets whittled down in Maisano’s post-Constitution article to fit his electoral strategy, so too does the concept of the class struggle. In his Constitution article, Maisano emphasized the broad political content of the class struggle in traditional socialism. A combination of the Utopian Socialist critique of capitalist property relations and the radical democratic egalitarianism of Tom Paine and the French Revolution, Marx and Engels created a theory of the class struggle that was opposed to exploitation and oppression of every kind, whether economic, political, religious, national, racial, or patriarchal. In the Jacobin/Bread and Roses strategy of “class struggle elections,” this broad conception of the class struggle gets narrowed down to across the board economic demands such as Medicare for all, raising the minimum wage, and support for unions. Racial, feminist, LGBTQ, and immigration struggles, even when fully justified and deserving of support for moral reasons, fall outside the category of “class” politics in Jacobin’s formulation.10 While this position has rightly been called class reductionist, Jacobin’s critics on this point haven’t entirely overcome their own form of reductionism, much as Horras couldn’t offer an adequate conception of mass politics to counter Maisano’s form of electoralism. Tatiana Cozzarelli’s “Class Reductionism Is Real, and It’s Coming from the Jacobin Wing of the DSA” is both a good summary of where this debate now stands and an example of how many self-described revolutionary socialists come up short when formulating an alternative.

Cozzarelli begins by defining class reductionism as “the belief that class causes all oppression and, in turn, that economic changes are enough to resolve all forms of oppression.” Eugene Debs’ view of race and socialism fits this definition— “There is no Negro question outside the labor question. The real issue… is not social equality but economic freedom. The class struggle is colorless.”—but Jacobin and Bread and Roses are not reductionists of this kind. They do not deny that there are struggles against particular oppressions that socialists should support and they do not hold that economic changes by themselves will resolve all other forms of oppression. They say that socialists should fight both the class struggle and other oppressions at the same time, though they view their so-called class-wide demands as strategically primary. Cozzarelli recognizes the difference between Jacobin and Debs and consequently adjusts her definition of class reductionism. Rather than saying that Jacobin reduces race to class, she, like R. L Stephens’ critique cited in note 11, says that Jacobin shrinks the concept of class to exclude race and other struggles from class. Quoting an often-cited passage from What Is to Be Done? (WITBD), Cozzarelli agrees with Lenin that a real socialist should “react to every manifestation of tyranny and oppression, no matter where it appears, no matter what stratum or class of the people it affects… and produce a single picture of police violence and capitalist exploitation… in order to set forth before all his [sic] socialist convictions and his democratic demands.”11 She then interprets this passage to mean that “fighting against racism is a class-wide demand,” that taking “up the demands of the most oppressed sectors of society… strengthens class consciousness and working-class unity,” that “socialists should be able to show that… socialist revolution is the path towards liberation for all oppressed and working-class people,” and that it is time for a mass politics not of the Jacobin economic electoral type but of socialist revolution.

There is a blind spot in this critique. The passage from Lenin that Cozzarelli quotes comes from the section of WITBD titled “The Working Class as Vanguard Fighter for Democracy,” and the quotation itself says that socialists should set forth not only their socialist convictions but also their “democratic demands.” Cozzarelli doesn’t ask why Lenin would call the working class a vanguard fighter for democracy rather than socialism. Nor does she inquire into what he meant by democratic demands or acknowledge that Lenin’s primary political goal was the establishment of a democratic republic. This neglect of the difference between democratic and socialist demands is its own form of reductionism and involves viewing and treating non-socialist mass struggles as if they were primarily opportunities for socialists “to show that socialist revolution is the path towards liberation for all oppressed and working-class people.” That’s a recipe for sectarian socialist preaching, not political leadership. Lenin’s approach was different.

I started reading Lenin’s agitational writings in late August 1971. After three years in SDS, I had joined the Revolutionary Union in Oakland following the invasion of Cambodia and the national student strike. On August 21, 1971, George Jackson was killed at San Quentin Prison, and I got the job of writing an article for the RU’s local monthly newspaper explaining why it was important for the working class to support the struggle that Jackson had waged against the prison industrial complex and for Black liberation. Putting the Black liberation struggle together with an as yet non-existent revolutionary workers’ movement in a coherent way was proving difficult, so the RU leader heading up the paper suggested I read “The Drafting of 183 Students into the Army,”12 a 1901 article by Lenin from Iskra, to get some ideas. The article, which was a report on the punishments meted out to university students demanding academic and political reforms from Tsarist authorities, read more like something from I. F. Stone’s Weekly than one of Lenin’s dense major polemics; but the bigger surprise came at the end of the article. In the conclusion, Lenin argued that “The workers must come to the aid of the students,” that the working class “cannot emancipate itself without emancipating the whole people from despotism, that it is its duty first and foremost to respond to every protest and render every support to that protest,” and that any “worker who can look on indifferently while the government sends troops against the student youth is unworthy of the name socialist.”

Even though I had read through most of Lenin’s major works over the previous year and a half, they were obviously too much to take in all at once. I hadn’t picked up at all on the parts of WITBD that called for opposing oppression of every kind. In SDS, support for the Panthers and the Black freedom struggle had always relied more on the national liberation rhetoric of Che and the NLF than on Lenin, partly because the Progressive Labor Party’s anti-nationalist workerism and bloc voting within SDS had given Lenin a bad name and partly because most discussions of Lenin were still centered on the hoary controversies over organizational centralism and socialist consciousness coming from outside the working class. The Iskra article forced me to reconsider what I thought I knew.

Reading back and forth through the first five volumes of the Collected Works, particularly the programmatic and agitational articles in volumes 2, 4, and 5, it became obvious that Lenin’s advocacy of “socialist” consciousness or “Social-Democratic” consciousness in WITBD did not just refer to consciousness of the need for socialism versus the Economist theory of trade union reformism, but also to consciousness of the need for already convinced socialists to support all other classes and groups in conflict with the Tsarist autocracy. On top of this double meaning of socialist consciousness, Lenin also used the terms “democratic” or “all-round political” at times instead of the more general “socialist” or “Social-Democratic” to refer specifically to the democratic content of anti-Tsarist political agitation and consciousness. Thanks to the work of Neil Harding13 and Lars Lih14, most of these terminological ambiguities in Lenin’s writings have now been cleared up, but not all. In my last article, I pointed out how Lih substituted the limited goals of freedom of speech and association for Russian Social-Democracy’s larger political goal of a democratic republic. In a related narrowing, Lih also blurs what Lenin meant by “class consciousness,” the “class struggle,” and “the class point of view.” Because I think the controversy between Lenin and his critics over the political content of these words is the most important ideological debate in the history of Marxism, we need to go over it in some detail.

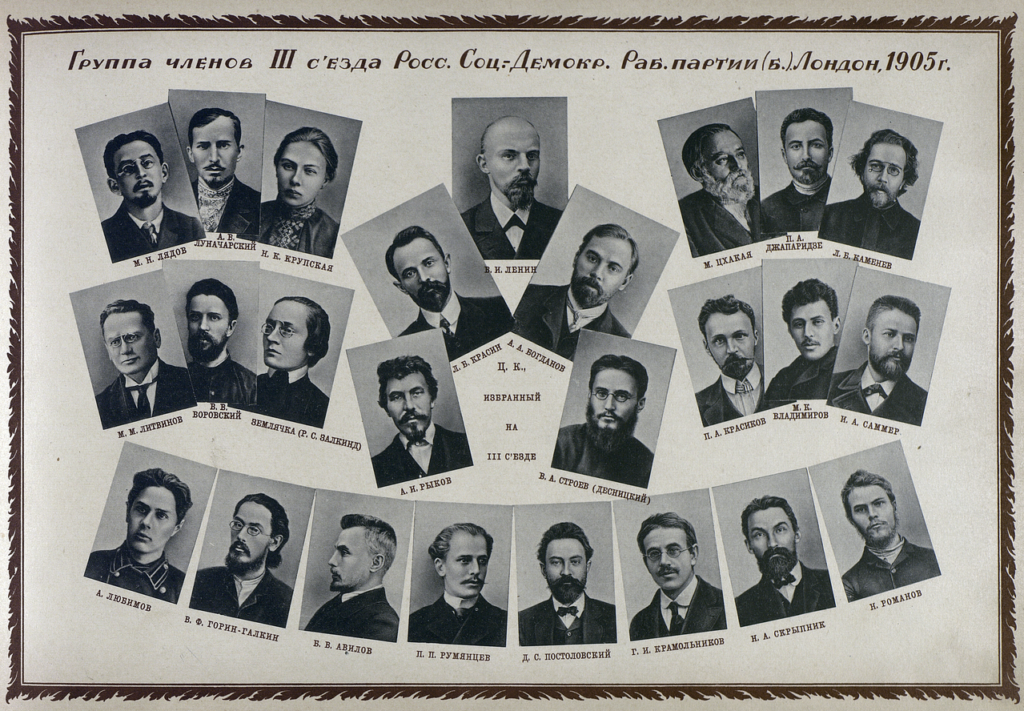

During the crucial years 1901-1904, both his Economist critics prior to the Second Congress and his Menshevik critics after the Bolshevik-Menshevik split accused Lenin of forgetting “the class point of view” because he placed the all-class democratic struggle against Tsarism ahead of the class struggle between workers and capitalists. Lenin’s eventual response to this criticism was that the strategy of the all-class democratic revolution was “the class point of view,” but it took him several tries and several months to state this theoretical position clearly. The phrase had first popped up in a letter sent to Iskra in late 1901, which Lenin printed and responded to in “A Talk with Defenders of Economism.”15The authors of the letter differed with Iskra both on the empirical evaluation of the readiness of the working class to engage in the political struggle against the autocracy and on the theoretical matter of how to engage in that struggle. They claimed that Iskra was seeking allies among other classes to fight the autocracy because it felt that the working-class movement was too weak to challenge the autocracy on its own. It was, they said, this impatience with the low level of working-class activity that led Iskra to depart from “the class point of view” and downplay the working class’s differences with these other classes. In the authors’ opinion, the working class first needed to build up its own strength in the economic struggle against the employer class before it could graduate to the political struggle against the autocracy. It was therefore the fundamental task of Social-Democratic literature to criticize the bourgeois system and explain its class divisions, not to obscure these class antagonisms by seeking allies among other classes.

Of course, Lenin disputed every one of these points. The spontaneous awakening of the workers and other social strata had already outgrown the ability of the Social-Democrats to keep up. This spontaneous upsurge demanded that the Social-Democrats abandon their local insularity and join Iskra in forming a nationwide organization to coordinate the struggle against the autocracy. As for abandoning “the class point of view” and neglecting “close, organic contact with the proletarian struggle,” Iskra was proud of its efforts to rouse political discontent among all strata of the population and never obscured “the class point of view” when doing so. It was Social-Democracy’s obligation to lead the democratic struggle against the autocracy, otherwise political leadership would fall into the hands of the bourgeoisie and cripple the working class’s ability to shape the future of the country.

The main thing to note about this response is that Lenin did not claim at this point that the democratic struggle against the autocracy was a direct expression of “the class point of view.” He was still operating within the framework laid out in his programmatic essay from 1898, “The Tasks of the Russian Social-Democrats,” before Economism had emerged as an explicit trend. In “The Tasks,” Lenin divided the working-class struggle into two branches, the “socialist (the fight against the capitalist class aimed at destroying the class system and organizing socialist society), and democratic (the fight against absolutism aimed at winning political liberty in Russia and democratizing the political and social system of Russia).”16 To be sure, Lenin held that both of these struggles were parts of the single overall Social-Democratic class struggle of the proletariat, but his emphasis was on delineating the different characteristics of each. The rhetorical move of the Economists in 1901 was to appropriate the socialist/economic half of this dual class struggle and claim that it alone constituted “the class point of view.”17 Lenin bridled at this attempt by the Economists to seize the high ground in the rhetoric of the class struggle, but he did not yet directly counter it.

Lenin had received the Economists’ “Letter” while he was already in the middle of writing WITBD and immediately made it the focal point of his critique. As he wrote in the “Preface” to WITBD, “A Talk with Defenders of Economism” “was a synopsis, so to speak, of the present pamphlet.” The last part of the section in Chapter III titled “The Working Class as Vanguard Fighter for Democracy” (the section from which Cozzarelli draws her quotation) was devoted to responding in more detail to the Economists’ letter. However, although there is more detail, Lenin’s theoretical framework remained essentially the same. While he added many passages where he argued that “Working-class consciousness cannot be genuine political consciousness unless the workers are trained to respond to all cases of tyranny, oppression, violence, and abuse, no matter what class is affected,” when he came to the “the class point of view” phrase his tactic was to undermine its pretensions rather than to take it over as his own. It was not until the article, “Political Agitation and ‘The Class Point of View,’” that he made the latter move.

Although “Political Agitation” appeared in the February 1902 issue of Iskra before WITBD was published in March, it was written after WITBD was completed.18 My guess is that the time pressure of getting WITBD out to the activists in Russia precluded any more modifications, yet Lenin felt there was still a loose end that needed tying up. “Political Agitation” starts off with a review of an incident in which a member of the Russian nobility by the name of Stakhovich gave a speech to a local Zemstvo [landlord] assembly calling for freedom of religion. The pro-autocracy conservative press denounced the speech and reminded the noble that it was only because of the power of the police and the Orthodox Church’s theology of absolute obedience to authority that the landlord class could keep its control over the peasantry and continue to eat well and sleep peacefully. Lenin then commented that the state of affairs in Russia must really be in dire straits if even members of the nobility were becoming dissatisfied with the tyranny and incompetence of the priests and the police. Of course, Lenin went on, we know that the conservative press cannot discuss openly why dissatisfaction with the autocracy was reaching even into the ranks of the landlord class, but it was a real mystery why many revolutionaries and socialists seemed to suffer from the same disability: “Thus, the authors of the letter published in No. 12 of Iskra, who accuse us of departing from the ‘class point of view’ for striving in our newspaper to follow all manifestations of liberal discontent and protest, suffer from this complaint.” They were like the writer who asked Iskra in astonishment: “Good Lord, what is this—a Zemstvo paper?”

Lenin continued:

“All these socialists forget that the interests of the autocracy coincide only with certain interests of the propertied classes, and only under certain circumstances…. The interests of other bourgeois strata and the more widely understood interests of the entire bourgeoisie… necessarily give rise to a liberal opposition to the autocracy…. What the result of these antagonistic tendencies is, what relative strength of conservative and liberal views, or trends, among the bourgeoisie obtains at the present moment, cannot be learned from a couple of general theses, for this depends on all the special features of the social and political situation at a given moment. To determine this, one must study the situation in detail and carefully watch all the conflicts with the government, no matter by what social stratum they are initiated. It is precisely the ‘class point of view’ that makes it impermissible for a Social-Democrat to remain indifferent to the discontent and the protests of the ‘Stakhoviches.’”

It is in the last line of the quotation above that Lenin turns the tables on his critics and introduces for the first time his own conception of “the class point of view.” He then proceeds to explain where this conception comes from:

The reasoning and activity of the above-mentioned socialists show that they are indifferent to liberalism and thus reveal their incomprehension of the basic theses of the Communist Manifesto, the ‘Gospel’ of international Social-Democracy. Let us recall, for instance, the words that the bourgeoisie itself provides material for the political education of the proletariat by its struggle for power, by the conflicts of various strata and groups within it….

Let us recall also the words that the Communists support every revolutionary movement against the existing system. Those words are often interpreted too narrowly, and are not taken to imply support for the liberal opposition. It must not be forgotten, however, that there are periods when every conflict with the government arising out of progressive social interests, however small, may under certain conditions (of which our support is one) flare up into a general conflagration. Suffice it to recall the great social movement which developed in Russia out of the struggle between the students and the government over academic demands [the drafting of the students], or the conflict that arose in France between all the progressive elements and the militarists over a trial [the Dreyfus Affair] in which the verdict had been rendered on the basis of forged evidence. Hence, it is our bounden duty to explain to the proletariat every liberal and democratic protest, to widen and support it…. Those who refrain from concerning themselves in this way (whatever their intentions) in actuality leave the liberals in command, place in their hands the political education of the workers, and concede hegemony in the political struggle to elements which, in the final analysis, are leaders of bourgeois democracy.

The class character of the Social-Democratic movement must not be expressed in the restriction of our tasks to the direct and immediate needs of the ‘labour movement pure and simple.’… It must lead, not only the economic, but also the political struggle of the proletariat….

It is particularly in regard to the political struggle that the ‘class point of view’ demands that the proletariat give an impetus to every democratic movement. The political demands of working-class democracy do not differ in principle from those of bourgeois democracy, they differ only in degree. In the struggle for economic emancipation, for the socialist revolution, the proletariat stands on a basis different in principle and it stands alone…. In the struggle for political liberation, however, we have many allies, towards whom we must not remain indifferent. But while our allies in the bourgeois-democratic camp, in struggling for liberal reforms, will always look back…, the proletariat will march forward to the end, …will struggle for the democratic republic, [and] will not forget…that if we want to push someone forward, we must continually keep our hands on that someone’s shoulders. The party of the proletariat must learn to catch every liberal just at the moment when he is prepared to move forward an inch, and make him move forward a yard. If he is obdurate, we will go forward without him and over him.

There is a lot packed into this short seven-page manifesto, and we can’t expand on all of it here, so I’ll just make a few comments before continuing with “the class point of view.” First, if anyone thinks that Lenin’s emphasis on democratic questions can be dismissed as a peculiarity attributable to living under an absolute monarchy without civil or political rights, think again. The Dreyfus Affair in France, a thoroughly modern bourgeois republic, is one of the two examples he gives of a seemingly minor conflict that flared into a general political conflagration. Lenin thought the Dreyfus Affair was so important as an illustration of why it was necessary to pay attention to even minor political conflicts, he pointed to it again in “Left-Wing” Communism”19 as a lesson for doctrinaires. Second, Lenin’s statement that there is no difference in principle between bourgeois and proletarian democracy, only a difference in degree, might sound strange to some; but that then is an indication of just how much has been lost in our understanding of the political content of classical Marxism. Third, when Lenin says that the proletariat “cannot emancipate itself without emancipating the whole people from despotism,” that should not be taken to mean that the emancipation of the whole people is a byproduct of the proletariat emancipating itself. Rather, as the vanguard fighter for democracy, the proletariat both leads and needs allies in the fight for democracy. Now, back to “the class point of view.”

Faced with the undeniable fact that the democratic political struggle against the autocracy was a multi-class struggle but that the economic struggle against the capitalists was a purely working-class struggle, Lenin had to find some standpoint from which he could claim that the democratic struggle represented the true working-class point of view. He did this by appealing to the Communist Manifesto, the “Gospel” of International Social-Democracy. Lenin argued that the theory of the working-class movement developed by Marx and Engels constituted the only true working-class point of view. Of course, Lenin was then accused of insulting the workers’ intelligence and perverting the meaning of socialism for claiming that socialist political consciousness could only be brought to the workers by bourgeois intellectuals from without. On this issue, I agree with Lih that this accusation was baseless and misguided from the beginning.20 Lenin and other orthodox Social-Democrats had the same right as any other political grouping to claim they represented the interests of the workers. On the flip side, however, neither they nor anyone else possessed any power to make the workers do anything they didn’t want to do. Workers have minds of their own and can choose to follow or become Marxists themselves, or not. Marx and Engels believed that the working class was the social force that embodied the potential to end all exploitation and oppression and dedicated their lives to helping realize that potential. Lenin followed in their path and elaborated his own distinctive interpretation of how to go about it in WITBD and “Political Agitation and ‘The Class Point of View.’” Whether we want to call it “the class point of view” or simply the democratic point of view, I think Lenin’s theory of democratic strategy and political agitation is still essential today because it is egalitarian, universal, systematic, and non-reductionist.

That finishes my review of Lenin’s theory of “the class point of view.” Because Lars Lih also discusses “the class point of view” extensively in Lenin Rediscovered, and because it seems that many people’s knowledge and impression of Lenin has been shaped or influenced over the past ten years by Lih’s work, I think a brief comparison of how our interpretations differ can further clarify the issues at stake.

Lih discusses the “the class point of view” in three places in Lenin Rediscovered, but none of these discussions include any mention or analysis of the “Political Agitation” article. As a consequence, Lih leaves out how Lenin turned the tables on his Economist opponents and took over “the class point of view” for his own purposes by basing it directly on the Communist Manifesto’s democratic political imperatives. Failing to acknowledge that Lenin put the phrase to this new use, Lih operates throughout Lenin Rediscovered with the Economist/Menshevik definition of the term, leading him to say at one point that Lenin’s political agitation focused so much on the theme of political freedom “that often it is difficult to remember that the author is a Marxist socialist. Of the twenty-seven articles in the [Iskra] series, only two contribute to the reader’s strictly Marxist education.” More than just a poor choice of words designed to highlight how different Lenin was from his opponents, Lih here completely muddles the question of what constitutes Marxism. Satisfied with Karl Kautsky’s general formula about the merger of socialism and the workers’ movement, Lih avoids confronting Lenin’s insistence that a more definitive dividing line between real Marxism and lip service Marxism can be drawn based on Marx’s and Engels’ political writings. With this overview in mind, let’s see how Lih’s approach plays out in his specific comments on “the class point of view” controversy

Of Lih’s three comments on “the class point of view,” the one on the Economists’ “Letter” is the most important. The other two, both of which involve a later dispute with the Mensheviks, are variations on the first.21 Lih’s summary of the Economists’ “Letter” and mine are the same, except on one point. Lih writes that “The central dispute is empirical [about the strength of the mass movement] rather than theoretical.”22 I find this minimization of the theoretical differences between Lenin and the Economists baffling. Lenin’s and the Economists’ disagreement over what constituted “the class point of view” was a disagreement over the political content of the class struggle, not just “optimism” or “skepticism” about the strength of the popular movement at a particular point in time. Clear evidence that the content of class political consciousness was a distinct issue separate from any estimation of the strength of the mass movement comes from the attitude of one of Lenin’s other political opponents, the newspaper Rabochee delo.

Rabochee delo was, like Iskra, also enthusiastic about the strength of the mass movement in 1901, but that did not then cause it to adopt Iskra’s politics and Lenin’s “class point of view”. When faced with this dispute between Iskra and Rabochee delo over ideology and tactics rather than the dispute over the level of the mass movement, however, Lih chooses not to take a position on which of the two was more grounded in the works of Marx and Engels. He settles instead for the noncommittal observation that both were principled advocates of Erfurtianism who happened to differ on how “to apply Erfurtianism in the current Russian context.”23 It is here that the weakness of Lih’s concept of Erfurtianism comes into play. Lenin’s whole point was that general pledges of allegiance to the goal of socialism were insufficient. The struggle for democracy and socialism also required specific tactical plans and a commitment to developing a specific kind of political consciousness, imperatives that Lenin claimed were drawn directly from Marx, Engels, and the Communist Manifesto. While Lih refrains from any detailed investigation into whether Lenin’s claim was justified, he does make a long comment in a footnote24 on Lenin’s “The Tasks of the Russian Social-Democrats” regarding Kautsky’s merger formula that indicates he genuinely does not understand what Lenin was saying. Because his comment is long, I’ll put my reply to it in a footnote25 and end this review of Lih with the conclusion that Lenin was justified in his claim that his political theory was drawn directly from Marx and Engels and that it is right to say that Lenin’s theory of democratic political consciousness and the goal of a democratic republic was and is the “strictly Marxist” position.26

I’ll end this article where it began, with the beginning of Jacobin. The same Issue 2 that contained Ackerman’s Constitution article also contained an article by Chris Maisano titled “Letter to the Next Left,” a reflection on C. Wright Mills’ “Letter to the New Left” from fifty years earlier. Maisano argued that Mills was wrong to think that intellectuals were the new agents of historical change who could take over the leading role traditionally played by the working class in Marxist ideology. Believing in the working class as the leading historic agency for radical change is not a “labor metaphysic,” Maisano wrote, “it’s a recognition of the enduring realities of life under capitalism.” In the next issue, Pam C. Nogales responded to Maisano in “Two Steps Back,” arguing that Maisano misunderstood what Mills was trying to say. Mills wasn’t saying that intellectuals were a new class that could replace the working class as the central agent of historical change, but that intellectuals had an important role to play in examining the reasons why the working class had ceased to act as a transformative historical force. Nogales was right about Mills. He was asking the Left to reflect on its history and its current condition in order to formulate new perspectives and new theories that might help reconstitute the Left as a political subject. He wasn’t dismissing labor as a potential political actor— “Of course we cannot ‘write off the working class.’… Where labor exists as an agency, of course we must work with it”— what he meant by political agency was the traditional Marxist commitment to liberate all of humanity from the terrors of war, colonialism, economic exploitation, and racial oppression. During the Cold War in the U. S. and Great Britain, there was no longer any mass working-class movement actively interested in these goals. Mills was saying that intellectuals should not stand by and wait for the working class to act but should begin on their own the intellectual and political process of reviving the discussion of the traditional Marxist goal of human liberation. His final bit of advice to the New Left at the end of his letter was “Forget Victorian Marxism, except when you need it; and read Lenin again (be careful)— Rosa Luxemburg, too.” In this cryptic shorthand, Victorian Marxism stood for the economic interests of the working class while Lenin and Luxemburg represented the universal emancipatory core of Marxism. When Maisano, Ackerman, and Jacobin in general explore the history of the struggle for democracy over more than two centuries in the U. S. and Europe, they are acting in the emancipatory tradition of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Luxemburg. When they settle for the strategy of “class struggle elections,” they are falling back into Economism and the labor metaphysic.