Debs Bruno and Medway Baker lay out the conditions of the current crisis, the political potentials it opens up, and the need for a socialist program to pave a path forward.

As COVID-19 rages through the shell of a global civilization systematically ravaged by five decades of catabolic capitalism, the facades of processual stability are crumbling and revealing, in their place, a crossroads for human society. The illusion of stability and robustness projected upon the delicate systems of production, distribution, exchange, and social reproduction has long been predicted to evaporate. Yet the prophets of this revelation have long been marginal– considered doomsday prophesiers and malingering malcontents besotted by their own unpopular utopian aspirations. Now, in the wake of a challenge to those processes’ perpetuation – a challenge unprecedented in the annals of fully-developed, advanced global capitalism – such grim prognostications are being rewoven, this time into the weft of history.

The tasks of socialists, spectating from within the structure as it has been stripped down to the girding beams and beyond, are to clear-headedly analyze the conjuncture at which we find ourselves, identify the opportunities and dangers that conjuncture creates, and to organize at the weak points which yield the greatest leverage for reusing the rubble that results. The first part of this charge promises us a head-spinning voyage. Almost nobody alive has experienced a societal crisis of this scale, and absolutely nobody alive has experienced a menace of this nature. Furthermore, the suite of contingencies within which this havoc has arisen and within which it is doing its work have never before existed.

The imperial core has, in the course of realizing its ineluctable tendencies, hollowed itself of the substance of its self-perpetuation. The production networks have exogenized themselves, expanding for their continued competitiveness beyond the outer membrane of the core itself and relocating in territories still fertile for exploitation. On the foundation of world destruction following the Second World War, capital has created a global network of energy and resource flows, sending the production of value and the extraction of resources to postcolonial and economically colonized nations in the Global South and the periphery broadly. In the core Western nations, coronated by the whorls of history as the center of this global web, the increasingly costly machinery of capital production has been either left to rot or cannibalized in favor of an ethereal finance economy. The tools of leverage and speculation are used to direct the operation of the global system as a whole while little of substance is produced in the formerly unrivaled center of commodity production. This, however, creates a contradiction. Absent the productive and social apparatus which put the core in this privileged position, the nerve center of global capital has stripped its muscle and hollowed the bone. The aberrant wealth and power resulting from the annihilation of the two imperialist wars of the 20th century have evaporated, and a crisis of reproduction– ecological, political, cultural, and economic– has matured.

The foundering of profitability, meanwhile, has required the abortion of such regulatory mechanisms as had previously placed a limit on self-destruction, leaving the interior composition of the capitalist core bound, sedated, and ripe for predation. The exportation of ecocide, genocide, and the iron-heeled boot have become impossible; there are no boundaries in interpenetrated systems, and the segmentation once feasible has given way to self-reinforcing, malign cycles of crisis in infrastructure, geopolitics, social degradation, and ecological death.

The political systems of the core’s constituent nation-states have responded accordingly, as the coalition of interested groups inherited from the Fordist Bretton-Woods system has steadily seen its legitimacy and ability to navigate exigencies eroded. In place of the ironclad sovereignty this coalition once enjoyed, chasms have yawned– and nature abhors a vacuum. Into this void have rushed various strains of reaction, most retrograde, whether from the right or the left. In a way, the current presidential contest in the United States represents a popularity contest between various past eras to which to return: Trump wants a return to the post-historical jouissance (or doldrum-plagued interregnum, depending on whom you ask) of a mythical 1990s; Sanders to the New Deal-inflected, postwar imperial sugar-high that reigned during the 1950s and 60s class compromise; Biden to the last-ditch resuscitation of the Third Way characteristic of the late 2000s; and Marianne Williamson to the Zoroastrian golden age of 1500BCE. None of these alternatives are viable, as the preconditions for their existence no longer exist. But some of them represent the extremely powerful but heretofore latent rejection of the absurdly non-functional status quo, while the rest do not.

Many of us had hoped to have at least the ten remaining years promised us to avert certain climate catastrophe as a political deadline, and some had projected relative stability further into the future. Socialists within or adjacent to the Sanders campaign and its attendant parapolitical formations had hoped that a demonstration of its inability to implement its program would further the radicalization and cohesion of a left mass politics. This was a form of impossibilism, it has been argued, but one which could conceivably have worked along the lines it promised. The handlers of the neoliberal consensus had hoped that an exposition of the (clutch pearls now) utter incivility of the perfunctory right-populism of the Trump orbit would enable them to slowly reorient the official political sphere back into carefully-managed, popularly unaccountable, and technocratic halcyon typified by the Obama years. Neither of these alternatives are any longer possible, and the mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic points to the deeper systemic reason why, illuminating with it our overdetermined spiral into the event horizon of total catastrophe.

The structural impossibility of an effective response to the economic crash of 2007-8 made it inevitable that a more deeply impactful repetition of that crisis would manifest within the normal course of the capitalist business cycle. The overextension and simultaneous neutralization of fiscal and monetary measures introduced to reinflate doomed financial mechanisms and speculation has additionally made certain that the next capital-elimination event would be largely intractable to the top-down treatments required to sustain neoliberal suspension of profit-rate decline. In sum, we knew that another, more system-shattering crisis was coming and that it was coming soon. We could not know what event would precipitate it nor even foggily apprehend what the result would be. It is very possible that we now know the first. What we must do now is to address the second.

Intimations as to the sorts of social and political reactions to this crisis are beginning to coalesce. In recent days, the social-democratic proposal for the maintenance of the slowly disintegrating capitalist system having been roundly rejected, two main strains of response have surfaced. The first of these is a cataclysmic abdication of the concept of governance and even of society as an organ. This is best embodied in the United Kingdom’s policy of pursuing what is misnamed “herd immunity”. Actual herd immunity is not the purpose or result of this strategy. Instead, what it proposes is inaction. While the United States has de facto gone the same route due to incompetence and the total absence of social infrastructure, Boris Johnson has affirmatively asserted that the UK’s response will be to not respond. This will, as everybody knows, result in the expiration of approximately 3% of British people and the utter disintegration of the British economy, but, in Johnson’s theory, will then produce returned stability after everyone who could die from this virus has done so. Perhaps he views the lives lost along the way as more extirpation than expiration.

The Johnson approach is consonant with that of the United States and, oddly, Sweden. The key difference is that, while the central political figures in the US are surely indifferent to the eventuality spelled out above, they are at least feigning interest in taking tepid steps toward mitigating the catastrophic effects of that approach. Proposals from such figures include the following: from Trump, lying about having already accomplished the initial stages of a pandemic response; from Joe Biden, providing limited financial assistance to healthcare providers and public health organizations for the duration of the first wave of infections, thereby allowing otherwise helpless populations to access treatment; from Bernie Sanders, the same universal healthcare proposal he has advocated for decades; and from Nancy Pelosi, et al., provision of two weeks’ paid sick leave for about 20% of American workers. This constitutes a less-than-total abdication of governmental responsibility– with just enough prevarication to ensure that levels of hatred for the US stay steady but do not increase.

More interestingly, however, is the second strain of political response to the many-sided crisis precipitating around COVID-19. This strain is one that has been developing potentiality for many years, but which has, until very recently, remained embryonic and subterranean. Slavoj Zizek recently assessed the political situation in the United States as increasingly four-faceted. His categories fell roughly along the lines of neoliberal-establishment, neo-conservative establishment, right-populist, and left-populist. There are valid objections to this framing, but in the interest of this analysis, we can retain the idea that, despite appearances, the political polarity is between neoliberal-neoconservatism, straining mightily to maintain its stranglehold on the formal-political, and rupture-seeking populisms on the left and the right. Zizek’s analysis suffers from diffraction: there are not four faces, but two. There exists a backward-looking political contingent, comprising the cores of both major parties. And there is a rapidly-condensing sentiment which is formulating from the far right a politics which, in the United States, at least, is entirely new. If we accept the notion that politics is only politics in the millions, there is no forward-looking left.

The left-ruptural cohort has yet to promulgate a political vision which supersedes what it has already tried: a politics it has never stopped fighting to implement in the course of US labor history. The right-ruptural faction, on the other hand, appears to have formulated something novel and unspeakably dangerous. The mere appearance of an articulation seeking an alternative rather than a facially-improved continuation of the present arrangements is revolutionary in the post-neoliberal moment. And, as in all revolutionary epochs, the possibility for seizing the vlast – for challenging the sovereignty of the present regime and seizing it for one’s own political project – flows to the right as well as to the left. It is evident that the political center has almost fully fallen away and that a new center of gravity which will frame a new political polarity is inevitably on its way. The neoliberal hell-halcyon is as good as dead. The question that remains to us is what new social conjuncture will follow it.

The gravest threat, therefore, is neither (as most readers will agree) Donald Trump or “Trumpism”, as the liberals bray, nor the Democratic Party inertia-machines. Nor is it mass catatonia, although that threat and its ecological implications rank higher than either of the two former monstrosities. Instead, the true nightmare scenario against which we must be vigilant and organized is presented by what we have called the “Carlson Effect”. Sensing, as anyone with cortical function probably has, that the winds are shifting, elements of the American right (parallel to various European right parties and populations) have at least rhetorically embraced a vigorous right-populism tending, even, to social-fascism. At the time of writing, there have been at least three calls from prominent figures in or adjacent to the Republican Party for social provision to those deemed to be “real Americans”. Mitt Romney, the billionaire Mormon, ex-presidential candidate, and longtime denizen of the lounges of Republican Party officialdom, last week called for a $1,000 payment to offset the financial ruin in store for half of US workers in wake of the indefinite suspension of their employment. Crypto-fascist Senator Tom Cotton today decried the ersatz and indirect system of tax credits used for social provision, calling instead for a similar UBI-esque policy.

While, at first glance, these programs appear to be much-needed and overdue relief for millions of Americans barely clinging to the economic margins, they are very likely the opening shots in a coming salvo of right-populist political sentiment. A salvo which will certainly vouchsafe the irrelevancy of any left movement – and maybe even violently suppress such a movement – for generations. Of course, we would never take a position counter to the material alleviation of the suffering of the working class over insignificant political quibbles regarding who is providing that relief. The objection, however, that we should raise to this politics is not insignificant quibbling.

Any program of social provision implemented by the virulently nativist, white supremacist US ruling class or their political lickspittles will contain within it exclusionary mechanisms that will demarcate the populations they wish to recruit to their politics. Communities most affected by the grindstone of capitalist destruction will inevitably fall shy of program requirements. They may lack sufficient citizenship status or be in debt to the Internal Revenue Service. They may have criminal records or (god forbid!) low credit scores. As the Democratic Party – never a champion of the working class despite over a century of too-clever-by-half attempts to subvert it from within – has withdrawn its constituency to the extent that it now solely serves the whims and aesthetics of a shrinking, cosseted coastal elite, the space for any collectivism has gone unfilled. This will not persist as the existing pressures intensify and new ones arise. Reform movements led or won by social-democrats do not carry us further from revolution and the emancipatory project. Reform movements helmed by fascists certainly do.

The goals of any politics which falls under the scattershot term “fascist” are bounded by the class nature of their constituent population segments. Fascism, in its minimum identifying features, is a socio-political movement that hijacks an existing mass-political framework or creates an ersatz mass-political appeal in service of the perpetuation of the current class relations. Fascism arises in times of capitalist crisis; they are socio-political responses to the possibility of revolutionary upheaval. They seek to curtail this possibility by forging unitary social institutions, crushing any deviant or dissenting factors, and accommodating the reintensified cannibalization of the social fabric and its extrinsic environment, both ecological and geopolitical.

The insufficiency and brutality of the US sociopolitical system was enough to spark in its populace anger, despair, non-participation, and social disease. Its collapse will generate a deconstruction of the former system’s constituent parts and their reassemblage into something new, which, as in all ruptural processes, will come into existence as a chimera of those parts and will gradually metamorphose into something entirely new. In a society based fundamentally on settler genocide, racialized caste relations up to and including race-based slavery, aggressively-pursued imperialism, and thoroughly insinuated anti-collectivism, that recombination is very likely to yield an atrociously destructive lusus nature.1

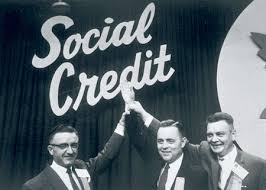

A peculiar manifestation of this kind of settler right-wing populism took shape in Western Canada during the Great Depression. This movement called itself “Social Credit”, after the economic theories of British engineer CH Douglas, although it rapidly took on a life of its own, separate from Douglas’s original formulations. Informally led by the deeply religious educator and radio show host William Aberhart, the movement rapidly acquired a grassroots base among the impoverished farmers of Alberta during the early 1930s, and swept Aberhart to electoral victory in 1935, heralding a virtual one-party rule in the province for the following 36 years.

Although Douglas’s economic theories are not particularly relevant for our purposes, it is useful to elucidate his philosophy, particularly his conception of “cultural heritage”, which, he said, entitled citizens to dividends based on their participation in society—essentially, an early form of universal basic income. In his own words:

“In place of the relation of the individual to the nation being that of a taxpayer it is easily seen to be that of a shareholder. Instead of paying for the doubtful privilege of being entitled to a particular brand of passport, its possession entitles him to draw a dividend, certain, and probably increasing, from the past and present efforts of the community [i.e., nation] of which he is a member…. Not being dependent upon a wage or salary for subsistence, he is under no necessity to suppress his individuality”.2

Douglas himself never intended to inspire a populist movement; he rather wished simply to influence economic policy through dialogue with the powers that be.3 It was Aberhart who brought social credit to the masses. Aberhart was quite literally a rabble-rousing preacher, spreading the word of God and social credit, denouncing the establishment politicians and finance capitalists, and promising his constituents a miraculous cure to the Depression. His radio audience ballooned as the economic crisis deepened, and his conviction inspired thousands to believe in him and his cause.

The specific financial measures he proposed were not so important as the message he propounded: There is no reason for our poverty! The bankers are robbing us! We, the people who work this land, must take what is rightfully ours! Douglas himself noted that

“it would not be possible to claim that at any time the technical basis of Social Credit propaganda was understood by [Aberhart], and, in fact, his own writings upon the subject are defective both in theory and in practicability…. [However,] it was at no time Mr. Aberhart’s economics which brought him to power, but rather his vivid presentation of the general lunacy responsible for the grinding poverty so common in a Province of abounding riches, superimposed upon his peculiar theological reputation.”4

Aberhart, in line with Douglas’s own theories, proposed that the state apparatus was in the hands of bankers who cared only about their own profits, not the common people. Although he attempted to convince the political establishment in Alberta of social credit policies, he was rebuffed, so he went to the people. Through his radio show, he tapped into the alienation of the impoverished workers and farmers of Alberta, their anger at the banks which drove them into eternal debt, their despair at the neverending Depression. He denounced, too, the mainstream media, the newspapers, for their failure to publish “the truth about the financial racketeers.”5 He framed himself as a man of the people, bringing the truth to the masses which the elites concealed from them. This scenario will be familiar to many of us today, in the age of television talk show hosts who seem to be displacing serious journalism in the popular consciousness.

Aberhart insisted that social credit would never involve confiscations of property, and that “production for use does not necessitate the public ownership of the instruments of production.”6 The explicit aim of social credit was an agreement between social classes, in which all citizens (i.e. members of the national community) would be taken care of. Aberhart explicitly counterposed class struggle to the “brotherhood of man”.7 “If we do not change the basis of the present system,” he exclaimed, “we may see revolution and bloodshed.”8 It was through “the common people stick[ing] together” that class warfare and violent revolution would be averted. 9

Indeed, while the labor movement was on the rise in other parts of the country, and the social-democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, now the NDP) was making gains in the neighboring province of Saskatchewan, the left was utterly crushed in Alberta, which remains a right-wing stronghold to this day despite the death of the Social Credit Party. The victory of right-wing populism in Alberta destroyed the capacity of labor activists and socialists to have any success for generations. In uniting the workers and petty bourgeoisie against the banks and the political establishment, social credit simultaneously staved off the threat of a genuine workers’ movement which could pursue its own, independent interests.

A comprehensive history of Social Credit rule in Alberta is well beyond our scope, but it is useful to highlight one incident which occurred under Aberhart’s Premiership, which involved government officials calling for the “extermination” of political opponents, termed “Bankers’ Toadies”. The leaflet they distributed read:

“My child, you should NEVER say hard or unkind things about Bankers’ Toadies. God made Bankers’ Toadies, just as He made snakes, slugs, snails and other creepy-crawly, treacherous and poisonous things. NEVER therefore, abuse them—just exterminate them!”10

This incident epitomises the type of threat presented by right-wing populism. While liberalism openly detests the masses and pretends at enlightened nonviolence while enacting the violence of the state, right-wing populists are unafraid to whip up popular sentiment against political opposition. This is the language of pogromists.

Although Aberhart was committed to realizing his program through constitutional means, the social credit movement did not remain committed to democratic principles. The right-wing thinks nothing of using force to crush dissent. If they are willing to take coercive and even violent measures against the capitalists to enact their program, the measures they are willing to use against workers are a thousand times worse. We must give the populist right the same treatment they would visit on us: we must exterminate them.

Regardless of what exigencies arise in the coming years’ political landscape, most of which are entirely obscured to us now, we can be certain of the crux of every political question: ecological collapse. Beyond the most obvious horror of this central question, the high-visibility catastrophes which will increase in magnitude and frequency, the tendrils of crisis will reach outward into every level of our social systems. Drought will spark agricultural collapse, which will cause multiple deluges of human migration, often all at once. Severe storms, flooding, weather-pattern changes, and sea-level rise will render major metropolitan areas functionally uninhabitable. The desertification of regions now devoted to large-scale monoculture or husbandry will disrupt critical commodity chains. This will doubtless cause armed conflict within and between nations.

We have likely all read these and many other dire projections and do not need to systematically enumerate them in order to demonstrate that whatever new mode of social organization coheres from the ashes of the old, it will be structured first and foremost by ecological catastrophe. This means, however, that during the collapse or slow disintegration of this social formation, a revolutionary program of clarity, urgency, and mass appeal never before attainable is possible to pursue.

Climate change is the skeleton key that unlocks the barred gate between us and the better world we struggle for. Every demand we now pursue in the interest of social justice, proletarian self-activation, and relief of sheer human misery will become a critical factor of our social system which has to be radically transformed in order to mitigate climate collapse. This means that any progressive, affirmative program of socio-ecological collapse constitutes, by the very nature of the adaptations required, a minimum program– a suite of demands which, when implemented, create the dictatorship of the proletariat and bring into the world real democracy for the first time. All other potential courses of action responsive to the general crisis coming down the pike are not only reactive and politically reactionary but will be insufficient to the scale of the calamity they respond to. The disastrous, sublime, terrifying situation we are now faced with lays down the gauntlet: we must either overcome our inhumanity and for the first time realize our collective potential, or consign the project of humanity to ignominy and extinction.

The retooling of society has already begun But we are in the premonitory tremors, so we cannot see around the curve. The present mode of economic relations, production methods, distribution mechanisms, political engagement, and energy production; our understanding of humanity’s position relative to “external nature”; the system of politically adversarial nation-states; those same nation-states’ positions in a rigid world-economic system; the presence of military conflict; social atomization – all of these elements of social existence and countless more will be altered by the metamorphic pressures of the coming total crisis. This inevitability creates two types of potential outcomes: the construction of an emancipatory, livable, fully-realized society; or the fall into a society increasingly composed along the barbaric trend-lines evident today. This epochal moment either breaks left, or it breaks right.

COVID-19 is not the harbinger of doom many subconsciously await with the sense of one waiting for the hammer blow to fall. It is, however, a signal and a model of the type of crisis we must anticipate and prepare for. The failure of the present could not be better illuminated than it is in the present disintegration. The present is intolerable and the future unthinkable. But to explore and demand the impossible is the task of revolutionaries, and our failure to take on this mantle will ensure our inability to seize the moment when future calamities emerge. To that end, we must formulate a program responsive to the needs of the masses of people, integrate ourselves into those groups most profoundly impacted by the implosion we are living through, and patch them together into a coalition capable of carrying our struggle forward into this brave new reality.

Responsive to this mandate, the formation of a new minimum program is the first and most urgent task of socialists today– particularly those in the West. We must begin to build a structured movement capable of responding, and even of assuming power the next time a civilizational collapse-level event emerges. And the first step in the way toward doing that is to build a program that addresses the critical needs of the masses of working people. The role of money, debt, stratospheric financial wizardry, foreign policy and international trade, and the structure of employment as a means of social control has never been more material than it is now. The purpose of those systems as a means of the restriction of access to resources has never been illustrated as clearly and starkly as it is right now. It is crystal clear which forms of labor are productive of value and which merely distribute, realize, and circulate value. It is also becoming clear how little of the value produced goes to the producers or to the general social good.

Critically, at a moment in which the US left is more nationalist than ever, this crisis is the first in an escalating series of crises that can only be remedied by internationalist socialism. The opportunity to promulgate a thoroughly internationalist politics and weave it into the existing left is the crux of this historical moment. Whether we do that will structure the outcome of the general collapse on its heels. Which fork in the path we choose may determine the survival of the species. The crossroads at which we stand must be understood as a unique opportunity to a) expand the class composition of the western socialist left; b) direct its politics in the necessary directions; c) incorporate swathes of working people toward a socialist politics of mutual self-interest; and, d) collectively take over the process of rebuilding (or not) the capital that will be destroyed by this many-sided crisis.

Moreover, this is a social rather than merely economic crisis, meaning it can only be effectively combatted through social solidarity, mutual aid, and democratically-run governmental initiatives. Economic crises often breed individualism, while more general, social crises breed mass politics and social cohesion. This is the first opportunity of this scale in many of our lives thus far, and we cannot let it pass.

In order to accomplish this essential task, the precondition for a socialist politics in the advanced capitalist core is being increasingly illuminated. This cornerstone is the precipitation of a mass, organized social movement with material social power which forms itself independent of and prior to participation in “official” politics. It cannot be wished into existence by way of electoral campaigns– especially not within the existing bourgeois unipolar political structure– or by trading in liberal-NGO cultural appeals. It must be built through the arduous, lumbering work of on-the-ground organizing. Fortunately for socialists, crises often catalyze the formation of such networks. We must attend to the material needs of our communities, build a package of demands responsive to those needs, and, in a coordinated campaign, target the crumbling mechanisms of maldistribution and social repression, and withhold our participation in them. There is no greater opportunity in recent memory to do so: people will be unable to comply with coercive maldistribution mechanisms such as rents and debt obligations, they will lack income but require the necessities of life, they will require medical care but be systematically denied access to it, and they will be exposed to hazards in the course of their work (should they have any) by indifferent or malicious capitalist corporations.

The contradictions are sharpening and they are incandescently clear for all who care to see. The socialist left often bandies this jargon about, often to the end of promulgating bad strategy and inadequate theory but in this case the process is actively accelerating and presents a crucial window of opportunity for real organizing toward social rupture.