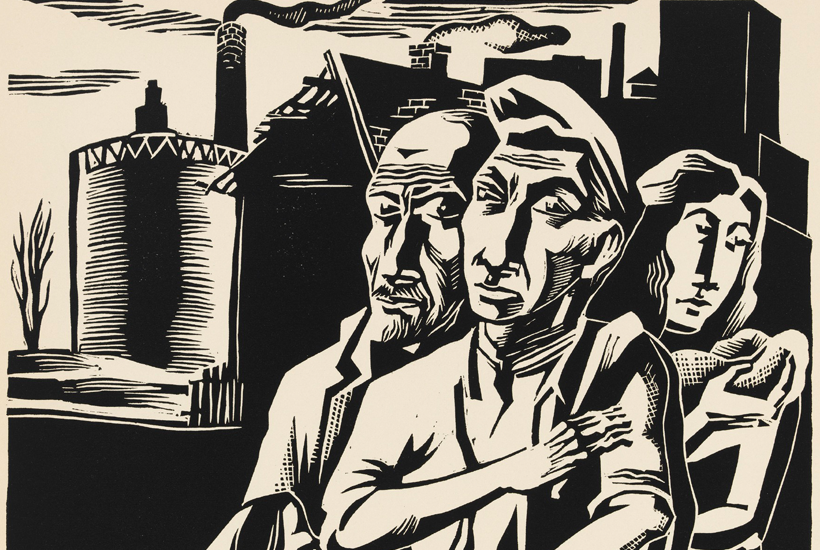

Chris Wright details the popular campaign for the Communist authored Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill, a moment in US labor history that is overshadowed by Roosevelt’s more conservative New Deal programs.

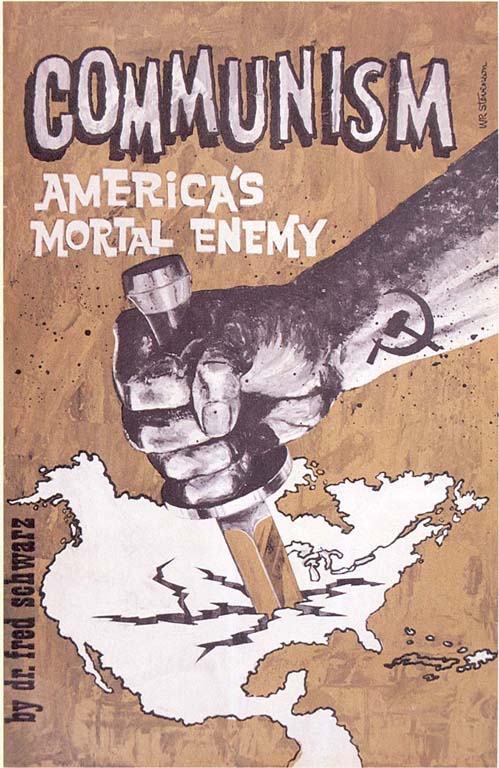

Historiography on the Great Depression in the U.S. evinces a lacuna. Despite all the scholarship on political radicalism in this period, especially the activities of the Communist Party, one of the most remarkable manifestations of such radicalism has tended to be ignored: the bill that was introduced in Congress in 1934, ’35, and ’36, the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill (called the Workers’ Social Insurance Bill in its 1936 version). This bill, originally authored by the Communist Party, was noteworthy in two respects: it was both very radical and very popular. In brief, it provided unemployment insurance for workers and farmers (regardless of age, sex, race, or political affiliation) that was to be equal to average local wages but no less than $10 per week, plus $3 for each dependent; people compelled to work part-time (because of inability to find full-time jobs) were to receive the difference between their earnings and the average local full-time wages. Commissions directly elected by members of workers’ and farmers’ organizations were to administer the system; social insurance would be given to the sick and elderly, and maternity benefits would be paid eight weeks before and eight weeks after birth; and the system would be financed by unappropriated funds in the Treasury and by taxes on inheritances, gifts, and individual and corporate incomes above $5,000 a year. In its 1936 form, it was particularly generous: it included insurance for widows, mothers, and the self-employed, appropriated $5 billion for the year 1936, established a Workers’ Social Insurance Commission to administer the system, and elaborated in much more detail than earlier iterations on how the system would be financed and managed.

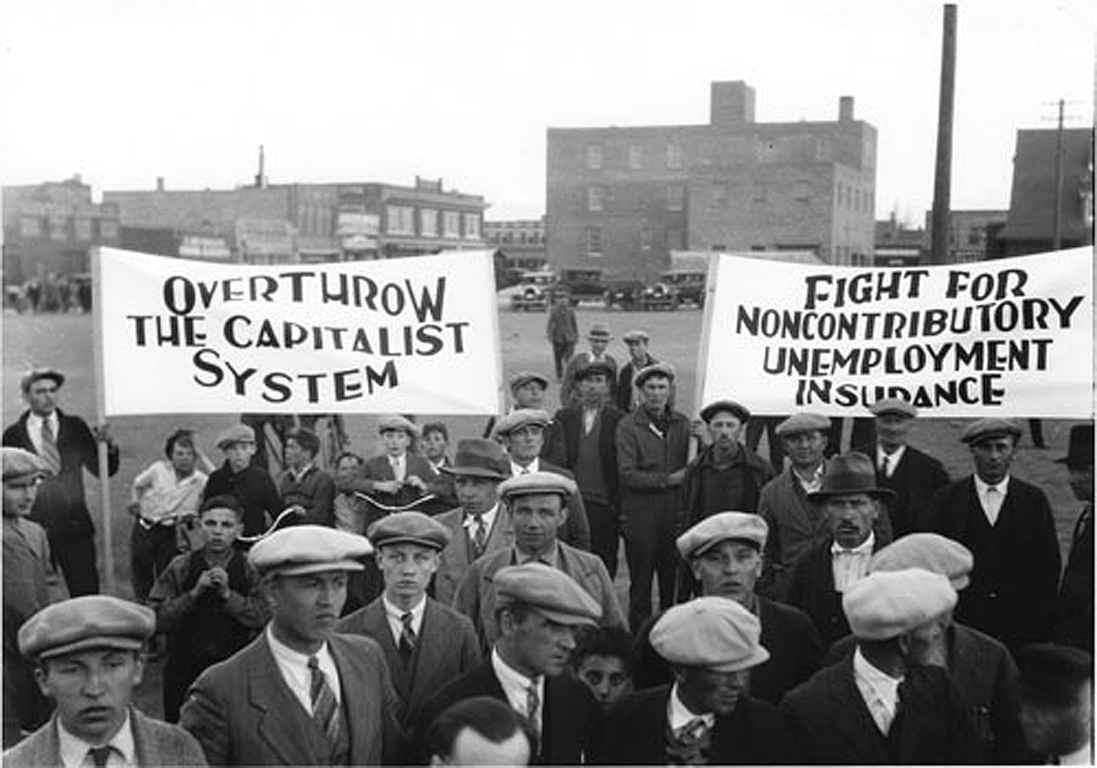

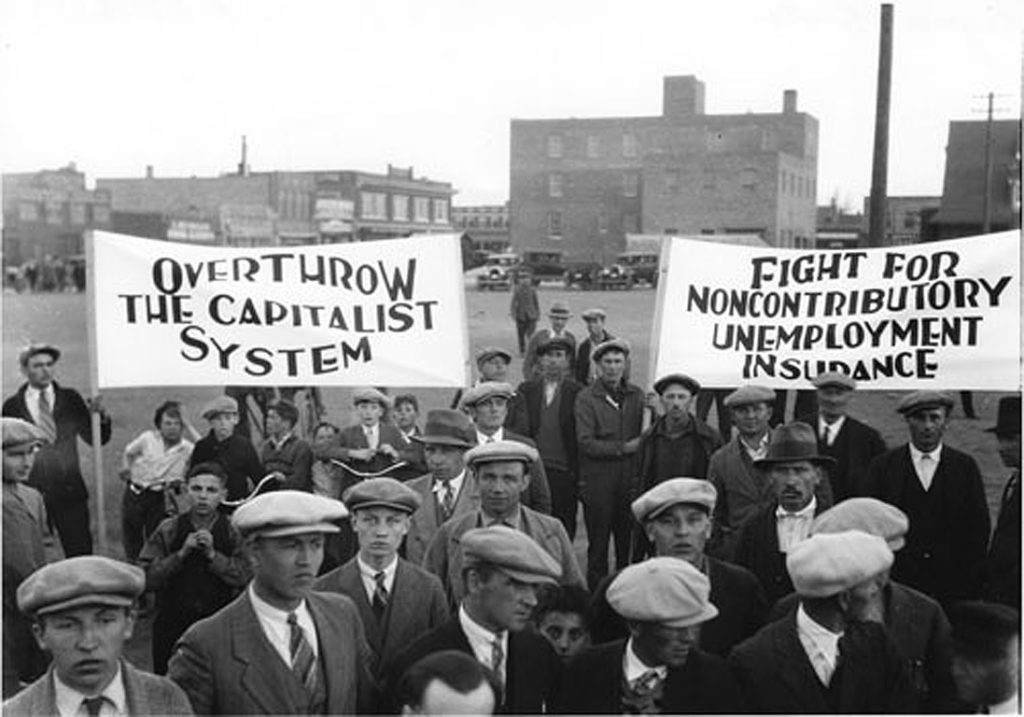

Despite, or rather because of, its radicalism, the Workers’ Bill attracted broad support across the country. To quote its advocates, by early 1935 it had been endorsed by “more than 2,400 locals [eventually about 3,500], and the regular conventions of five International and six State bodies of the American Federation of Labor; practically every known unemployed organization; thousands of railroad and other independent local and central bodies, fraternal lodges, veterans’, farmers’, Negro, youth, women’s and church groups…[and] municipal and county governmental bodies in seventy cities, towns and counties,” in addition to millions of individual citizens who signed postcards and petitions in support of it.1 All this support was not enough to get the bill passed in Congress, although in 1935 it was reported on favorably by the House Labor Committee. In fact, its provisions were so terrifying to the business class that it never had a chance of becoming law. What is interesting, however, is the momentum that developed behind it, despite what amounted to a virtual conspiracy of silence from the press and extreme hostility from conservative congressmen, business constituencies, and the Roosevelt administration.

Given the political and social significance of the Workers’ Bill, it is unclear why historians have largely ignored it. In a book called Voices of Protest (published in 1983), Alan Brinkley does not devote a single sentence to it. Neither does Robert McElvaine in his standard history, The Great Depression: America, 1929–1941 (1984). David Kennedy devotes half a sentence to it in volume one of his 2004 history of the Depression and World War II, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. Likewise, neither Ira Katznelson nor Jefferson Cowie mention it in their recent popular books, respectively Fear Itself (2013) and The Great Exception (2016). One reason for the neglect may be that the mainstream press tended to ignore it at the time, instead giving far more attention to the less radical—but also, arguably, less popular—Townsend Plan, an emphasis that historians have followed. In any case, in this article, I intend to rectify the historiographical oversight by telling the story of the Workers’ Bill—from the perspective of the popular enthusiasm it inspired—and arguing for its importance.

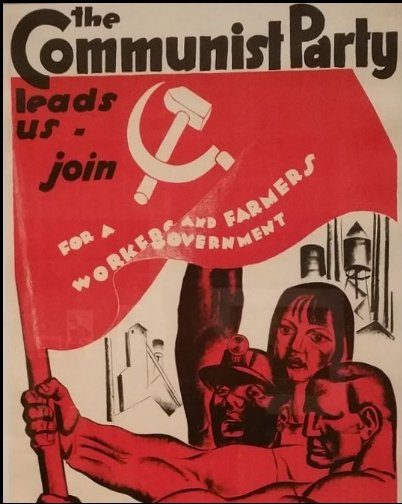

The history of the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill (in its various forms) began in the summer of 1930, when the Communist Party proposed its first iteration—an incredible $25 per week to the unemployed and $5 for each dependent—and immediately proceeded to agitate on its behalf. The reception that the unemployed gave this campaign suggests, contrary to what historians have sometimes argued, that it did not take long at all for a large proportion of the Depression’s victims to reject the voluntarist ideology of the 1920s and the Hoover administration in favor of massive government intervention in society for the purpose of income redistribution. By late summer of 1930, in the very early stages of the Depression, the Daily Worker was already reporting mass petition signings and continual demonstrations for the bill in scores of cities.2

In these early months, much of the agitation for the proposed bill was being done by the Unemployed Councils. We should recall that the Councils were being organized already in January and February 1930 and that urban areas of the country were in ferment a mere three or four months after the stock market crash of October 1929. Almost every day the Daily Worker reported mass meetings and marches on city halls in cities from Buffalo to Chicago to Chattanooga and beyond, by the spring spreading even to the Deep South. In the next few years the mass protests, including hunger marches, “eviction riots,” collective thefts, bootlegging, relief demonstrations, occupation of legislative chambers, etc., would surge from coast to coast; “hardly a day passed,” the historian Albert Prago writes, “without some major demonstration taking place in some town, city, or state capital.” As historians such as Roy Rosenzweig and Randi Storch have argued, at the forefront of much of this turbulence were the Communist Unemployed Councils.3

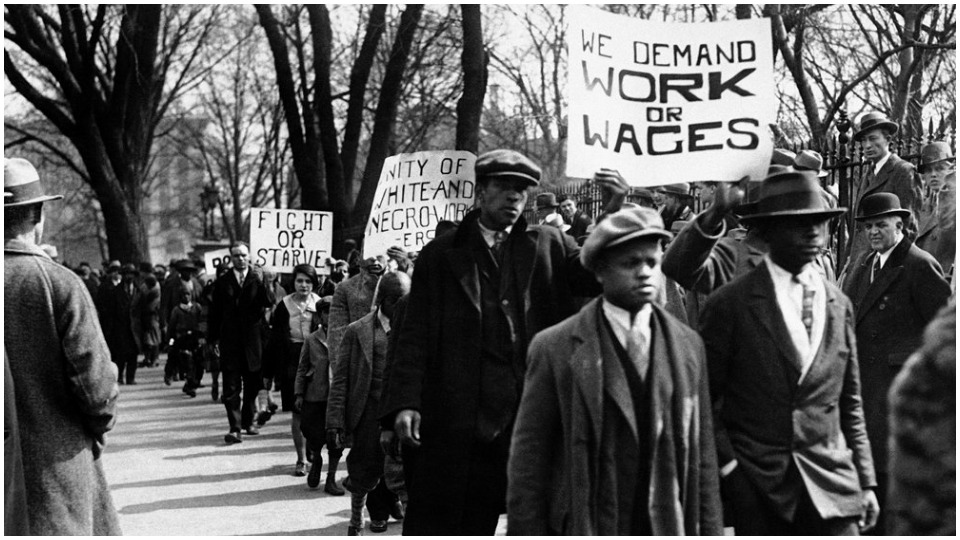

Even in February and March 1930, before the CP had officially proposed the Workers’ Bill, enormous demonstrations in cities nationwide featured the demand for “Work or Wages,” meaning either give us work or give us relief at full wage-rates. This demand already anticipated the Workers’ Bill, and within months evolved into the even more radical provisions of that bill. As the Unemployed Councils grew in the early 1930s, so did awareness of and support for the Communist bill.

The pace of actions died down a bit in the fall of 1930 but picked up again in December and January, in preparation for February 10, 1931, when 150 delegates elected from around the country were going to present the bill and its hundreds of thousands of signatures to Congress. Requests for signature lists flooded into the New York office of the National Campaign Committee for Unemployment Insurance from not only the large industrial centers but even towns and farms in the South and West, and Alaska. Metalworkers in Chicago Heights got involved in the campaign; railroad workers and section hands in Reno, Nevada signed petitions; letters like the following were sent to the Daily Worker:

Let me know what I can do to help carry forward the fight for unemployment insurance? This is the greatest need at this hour. I am the only reader of the Daily Worker here in Ashby, Minn., and am one of four Communist votes cast here in the elections. I am a woman of 60 years, living on land; I pass out all my Daily Workers to neighbors and am getting new subscribers. Will help all I can to get signatures for the bill.4

Countless united front conferences of workers’ organizations took place in cities around the country, for instance Gary, Indiana, where the keynote of one conference was sounded by an African-American steelworker and veteran of World War I who said, in part, “It’s no use going way over to France to fight. We can demand things here just as good as we can there, fight here just as good as there, and if need be, die here just as good as there… Let’s fight for ourselves, right here, now.” They fought in Charlotte, North Carolina; Ambridge, Pennsylvania; Wheeling, West Virginia; Minneapolis, Grand Rapids, and San Antonio; Hartford, Buffalo, and San Francisco. City hunger marches were so numerous in these months that the Daily Worker could not keep track of them. The Workers’ Bill, of course, was not the only or even the most pressing issue addressed by all these actions, but it did figure prominently among their demands. On the big day, February 10, demonstrations and state hunger marches occurred in at least 63 cities as the delegation in Washington, D.C. interrupted a session in the House and was forcibly ejected by police. In St. Paul, Minnesota, a certain type of action that was already becoming rather common: demonstrators broke through police lines around the state capitol and occupied the legislative chambers, announcing that they would not leave until the legislature had acted on their demands for relief and unemployment insurance.5

In short, arguably even before churches, charities, and benefit societies had conclusively demonstrated their inability to meet the economic crisis, well over a million people nationwide were demanding that the federal government become in effect a radically social democratic welfare state. In general, the statist orientation that Lizabeth Cohen discusses in Making a New Deal, which often was an extremely collectivist orientation (as embodied, e.g., in the Workers’ Bill), did not have to wait for Roosevelt and the New Deal to act as midwives, as Cohen and other historians seem to suggest. It emerged organically on the grassroots level, stimulated both by radical groups and by suffering people’s sense that society, with all its abundant resources possessed ultimately by the federal government, had to do something to end the epidemic of unjust suffering. Roosevelt and the New Deal were products of the country’s growing collectivism more than they were causes of it. And for many millions of Americans, they never went far enough.

Support for the Workers’ Bill grew during the next few years, with the help of continued demonstrations, petitions, postcard campaigns, and the efforts of radical unionists to enlist union members’ support. Hunger marchers in many states demanded that legislatures pass state versions of the bill. To take one example, Illinois saw at least four such marches to Springfield between 1931 and 1933, at the culmination of which a delegate delivered a speech before the legislature requesting enactment of the bill. The two national hunger marches Communists organized in December 1931 and 1932 gave publicity to the bill; on February 4, 1932, which the Communist Party had dubbed National Unemployment Insurance Day, hundreds of thousands of people around the country demonstrated for it. Petitions garnered thousands of signatures: in Chicago, for instance, during just three weeks in March 1932, over 30,000 people—in factories, AFL locals, public shelters, and neighborhoods—signed the bill, in preparation for May 2, when 200 workers “from all important industries from every section of America” were again going to present the petitions to Congress. Across the country, 1933 saw the organizing of numerous conferences of unemployed groups to coordinate the campaign for unemployment insurance and to prepare for the CP’s National Convention Against Unemployment in February 1934.6

Meanwhile, workers were waging their own battles in their unions, trying to get members, unions, and federations on record as supporting national unemployment insurance, preferably in the form of the Workers’ Bill. By late 1930, despite the opposition of the AFL (which was committed to the anti-government principle of voluntarism), many constituent organizations had called for legislation, including eight state federations of labor, the central labor bodies of nine cities, and the American Federation of Teachers, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, the ILGWU, the United Textile Workers, the United Hebrew Trades, and a number of other Internationals. Public pressure continued to mount in 1931, as 52 bills for unemployment insurance were introduced (unsuccessfully) in state legislatures. But at the 1931 AFL convention, the leadership was still able to smother the growing demand that the Federation change its voluntarist position. A rank-and-file movement, therefore, was organized in January 1932, when Carpenters Local 2717 in New York City called a conference of AFL unions. Representatives of 19 locals passed a resolution to appoint a committee—the AFL Trade Union Committee for Unemployment Insurance and Relief (AFLTU Committee)—that would gauge sentiment and build support among unions for the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill. In part because of its activities—and despite its being viciously persecuted by the national office as Communist—by the spring of 1934 over 2,000 locals and many central bodies had joined in its endorsement of the Communist-authored bill that Representative Ernest Lundeen had just introduced in Congress.7

The head of the AFLTU Committee was Louis Weinstock, a Communist member of the Painters’ Union in New York City. To advocate for the Workers’ Bill, which became the Lundeen Bill in 1934, he conducted a national tour that year, in each city contacting unionists who helped him organize meetings that hundreds of workers attended. Some cities had their own local AFL Committee for Unemployment Insurance, while in others Weinstock helped create one (or several). In reports to the Communist Party, he made some telling observations about the left-wing militancy of the local unions he encountered, as contrasted with the conservatism of the Internationals to which they belonged. For example, while some locals insisted that unemployed members should be able to remain in good standing even if they could not pay dues, Internationals were more likely to want to purge their out-of-work members. In many cities, building trades unions followed the practice of the Unemployed Councils in electing small relief committees to take members to a charity office and demand more relief. They often even united with the Councils in these activities, a tendency that, from the perspective of higher union officials, was growing to “alarming proportions” all over the country. Internationals, on the other hand, usually followed the conservative AFL line in its absolute rejection of cooperation with Communists, to the point that members who participated in Unemployed Council demonstrations risked being expelled from the union. In a case in Minneapolis, for instance, a local refused to accept the decision of its International that one of its members be expelled for having taken part in a Communist demonstration. The International replied that unless the union expelled her, it would have its charter revoked.8

But already by 1932, sentiment in favor of unemployment insurance had swept the large majority of rank-and-file unionists, in addition, of course, to the long-term unemployed whether unionized or not. Members were radicalizing, growing friendlier with Communists in their disgust at the inaction of union leaders. To quote Mauritz Hallgren, a keen observer of the labor movement,

although in the early years of the crisis they had tended to drift away from the unions, [jobless members] were in 1932 taking an increasingly active part in union affairs. The fear was expressed that in some organizations the unemployed might even come into control of the bureaucratic machinery. That they exercised a tremendous influence over local unions and city and state central bodies was seen from the avalanche of radical demands that poured in upon the quarterly meeting of the Federation’s executive council at Atlantic City in July [1932]. The rank-and-file workers, whether unemployed or not, were no longer to be put off with windy promises of action…9

After the powerful United Mine Workers endorsed the principle of government action at its convention in early 1932—which followed endorsements in 1931 by the Teamsters, the International Association of Machinists, the Molders’ Union, and many others—the AFL’s executive council saw the writing on the wall. It could prevaricate and postpone no longer; it had to accept, and propose at the next national convention, a version of compulsory unemployment insurance, thereby accepting the idea of government “interference” in the affairs of organized labor. But it certainly did not endorse the Workers’ Bill, or even the principle of federal action; instead, at the 1932 convention in November, the executive council recommended that the AFL endorse the idea of state unemployment insurance. Many of the delegates present considered this proposal too conservative, but nevertheless the convention approved it by an “overwhelming margin.” Not content with this victory, the AFLTU Committee continued its activism in the following years.10

As stated a moment ago, the growing support for the Workers’ Bill finally managed to get it introduced in Congress in early 1934, when Ernest Lundeen of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party sponsored it in the House (as H.R. 7598). While it fared even worse in this session of Congress than it was to fare in 1935, its presence at the federal level increased the momentum of its popularity among the working class. In Chicago, for example, leaders of the conservative local Federation of Labor began to have less success than in previous years preventing unions from endorsing it, as locals of the Railway Conductors, Railway Clerks, Machinists, Painters, Metal Polishers, School Custodians, Women’s Upholsterers, Granite Cutters, Millinery Workers, and many other unions sent delegates to a Communist-sponsored unemployment insurance conference in the summer of 1934. In July, representatives of 43,000 workers who were organized in fraternal and benevolent societies (specifically, in the Federation of Fraternal Organizations in Struggle for Unemployment Insurance) attended a hearing before the Chicago City Council to demand that that body support the bill; committees also visited aldermen in their wards to demand the same. In September, at another conference in Chicago, delegates from the National Unemployed Leagues, the Illinois Workers Alliance, the Eastern Federation of Unemployed and Emergency Workers Union, the Wisconsin Federation of Unemployed Leagues, and the Fort Wayne Unemployed League—in the aggregate claiming a membership of 750,000—endorsed the measure. Similar conferences occurred in other regions of the country.11

In January 1934, another organization had been founded that was to play an important role in lending academic respectability to the bill: the Inter-Professional Association for Social Insurance (IPA). While not officially affiliated with the Communist Party, it had close ties to leading Party members and coordinated its campaign for passage of the Lundeen Bill with organizations of the Left. Within a year it had dozens of chapters and organizing committees around the country, made up of both individual professionals and representatives of groups—nurses, physicians, actors, teachers, engineers, architects, authors, etc. The distinguished social worker Mary Van Kleeck of the Russell Sage Foundation led an army of her colleagues in supporting the bill and, in some cases, proselytizing for it in the press and before Congress. Economists and lawyers associated with the IPA testified to the economic soundness and constitutionality of the measure, especially in 1935, when Lundeen reintroduced it as H.R. 2827. Left-wing professionals considered it vastly superior to the Wagner-Lewis bill of 1934 and 1935—what became the Social Security Act—a professor at Smith College, for example, damning the latter as “a proposal to set up little privileged groups in the sea of misery who would be content to sit on their small islands and watch the others drown.” The Lundeen Bill (or Workers’ Bill) was certainly not without flaws, including its vagueness and, arguably, the financial burden it would impose on the country, but evidently, its Communist-style radicalism was so appreciated that even experts in their field were willing to overlook its defects.12

Significantly, it was in fact far more extensive than the Soviet Union’s measures for unemployment and social insurance. While the Lundeen Bill provided (among other things) for unemployment benefits for an unlimited period of time equal to 100 percent of wages—or much more, since an unskilled laborer with a wife and four children who might be lucky to get $16 a week would get $25 if unemployed!13—in Soviet Russia only about 35 percent of the customary wage was paid, and that for a limited time. Moreover, the various forms of insurance that H.R. 2827 would establish (unemployment, old age, maternity, disability, and industrial injury) were to be administered by councils of workers and their representatives, thus embodying a “workers’ democracy” that the Soviet system only lived up to on paper. In effect, then, the millions of Americans who advocated the measure desired a system that was, in some respects, more authentically communist/socialist than the Soviet one.14

A few days after Lundeen reintroduced his bill on January 3, 1935, the National Congress for Unemployment and Social Insurance was held in Washington, D.C., at the Washington Auditorium. Organized by the CP and its many allies, the congress comprised almost 3,000 delegates who had come by truck, jalopy, rail, box car, and on foot from every region of the country and forty states. To quote one historian, “cowboys from Colorado and Wyoming, black sharecroppers from Alabama, Texas oil hands, Florida housewives, skilled and unskilled workers, employed and unemployed” in the dead of winter made the pilgrimage to the nation’s seat of power, guided by visions of an egalitarian society, conscious that in their aggregate they directly represented millions and indirectly represented well over half the country. Unions of all types—professional, AFL-affiliated, independent; fraternal organizations and political groups; farm organizations and shop delegates; women’s groups, church groups, veterans’ groups, and unemployed groups—hundreds of such organizations, in an anticipation of the Popular Front, managed to overcome the congenital sectarianism of the Left and call as one for unprecedented social democracy. A few of the scores of lesser-known unemployed groups that were represented included the Chinese Unemployed Alliance, the Farmer Labor Union, the Italian Unemployed Groups, the Relief Workers League, the United Mine Workers Unemployment Council, the Workers Union of the World, the Right-To-Live Club, and the Dancers Emergency Association. The National Urban League, which endorsed the bill, also sent delegates.15

The legendary socialist and feminist Mother Bloor, who addressed the congress, pithily summed up its significance to a reporter from the Washington Post: “‘The congress is a success. It’s proved a big crowd of people can break down barriers of race, social position, political opinions, and convictions for a common cause. Why, there are white people and yellow people and black people out there.’ She nodded toward the mass meeting going on in the auditorium. ‘There are Communists and Socialists and Republicans. There’s even some Democrats.’” At the Congressional hearings on H.R. 2827, the chairman of the congress stated, not implausibly, that it had “formed the broadest and most representative congress of the American people ever held in the United States.”16

The Congressional hearings themselves were noteworthy. While the executive secretary of the IPA may have exaggerated when he wrote, “The record of the hearings on H.R. 2827 is one of the most challenging ever placed before the Congress of the United States and probably the most unique document ever to appear in the Congressional Record,” that judgment is understandable. Eighty witnesses testified: industrial workers, farmers, veterans, professional workers, African-Americans, women, the foreign-born, and youth. “Probably never in American history,” an editor of the Nation wrote, “have the underprivileged had a better opportunity to present their case before Congress.” The aggregate of the testimonies amounted to a systematic indictment of American capitalism and the New Deal, and an impassioned defense of the radical alternative under consideration. Witness after witness described the harrowing suffering that they and the thousands they represented (in each case) were enduring, and condemned the Wagner-Lewis bill as a sham. From the representative of the American Youth Congress, which encompassed over two million people, to the representative of the United Council of Working-Class Women, which had 10,000 members, each testimony fleshed out the eminently “class-conscious” point of view of the people back home who had “gather[ed] up nickels and pennies which they [could] poorly spare” in order to send someone to plead their case before Congress. Most of the Congressmen on the Labor subcommittee they were addressing were strikingly sympathetic.17

For example, when Herbert Benjamin, one of the leaders of the CP, had this to say on press coverage (or the lack thereof) of the Lundeen Bill—

So much has been said in the last few weeks about the Townsend plan [for old-age pensions]. I have discussed this question with a number of Members [of Congress], and they tell me that, outside of California, they received not a single postcard on the Townsend plan, but they received thousands of cards from all over the United States on the Lundeen Bill, asking for the enactment of this bill. Yet the newspapers, by reason of the fact that they really fear this measure and do not fear the Townsend plan, knowing that the Townsend plan can be a very good red herring to draw attention away from social insurance, have given publicity to the Townsend plan, and have yet avoided very studiously any attention to the workers’ unemployment and social-insurance measure—

the chairman of the subcommittee, Matthew Dunn, interrupted to say,

I want to substantiate the statement you just made about the Townsend bill and about this bill. Now, I represent the Thirty-fourth District in Pennsylvania, which is a very large district. May I say that I do not believe I have received over a half dozen letters to support the Townsend bill; however, I have received quite a number of letters and cards from the State of California. In addition to that, I have received many letters and cards from all over the country asking me to give my utmost support in behalf of the Lundeen bill, H.R. 2827.18

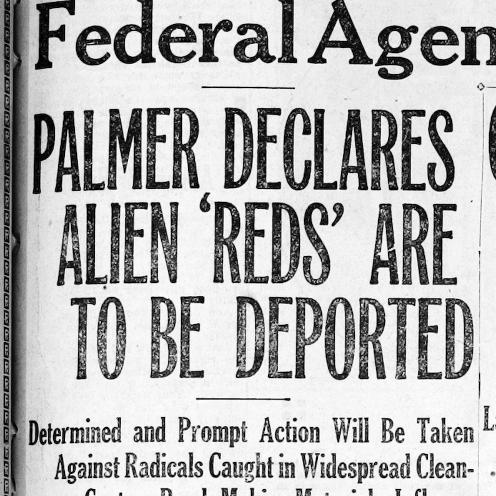

Incidentally, Benjamin’s complaint about press coverage was justified. Overwhelming press attention was devoted to the much less radical—and less economically sound—Townsend Plan, while virtually no coverage was granted the Lundeen Bill except during and after the subcommittee’s hearings, and even then it was mostly local papers that covered it. According to the executive secretary of the IPA, “forty-three news releases to all the news agencies and newspapers of the major cities during the course of two weeks [i.e., during the hearings] were, with few exceptions, suppressed, although in those outlying districts where organization has made the demands of the workers more articulate, some papers carried workers’ testimony as front page news.”19 As mentioned earlier, historians have followed newspapers’ lead by tending to ignore the Lundeen Bill and focus on the Townsend Plan, in some cases condescendingly interpreting the popularity of the latter’s provisions as evidence of the credulousness and simple-mindedness of the American public.20 This emphasis is unfortunate in that (1) it was the press that was significantly responsible for propagating the Townsend Plan (presumably to divert attention from the Lundeen Bill), and (2) the supposedly simple-minded public had the organizational sophistication and political savvy to build momentum behind a more reasonable bill premised on both the reality and the valorization of class conflict, not only without help from the press but despite active hostility from nearly all sectors of power—the press, the AFL, the Roosevelt administration, reactionary Southern landowners and politicians, and big business in general. Under such conditions, for example, organizers’ ability to get over five million signatures on their petitions was no mean achievement.21

Admittedly, compared to the number of signatures they likely could have collected had they possessed more resources, five million is not terribly impressive. In the spring of 1935, the New York Post conducted a poll of its readers after printing the contents of the Lundeen, the Townsend, and the Wagner-Lewis bills. Out of 1,391 votes cast, 1,209 readers supported the first, 157 the second, 14 the third, and 7 none of them. Of the 1,073 respondents who were employed, 957 supported the Lundeen Bill, 100 the Townsend Bill, 7 the Wagner-Lewis Bill, and 5 none. It would not be outlandish to infer from these findings that, had they known of the contents of the bills, a majority of working-class (and perhaps even many middle-class) Americans would have preferred Lundeen’s Communist-written one. This is also suggested by the enormous number of letters congressmen received on the measure, such as this one sent to Lundeen:

The reason I am writing you is that we Farmers [and] Industrial workers feel that you are the only Congressman and Representative that is working for our interest. We have analyzed the Wagner-Lewis Bill [and] also [the] Townsend Bill. But the Lundeen H.R. (2827) is the only bill that means anything for our class… The people all over the country are [waking] up to the facts that the two old Political Parties are owned soul, mind [and] body by the Capitalist Class.22

Feeling the pressure of this mass support, both the subcommittee and the House Labor Committee voted in favor of H.R. 2827 that spring, making it the first unemployment insurance plan in U.S. history to be recommended by a committee. It had no chance in the House, though. The Rules Committee refused to send it to the floor, although it allowed Lundeen to propose it as an amendment to the Social Security Bill (as a substitute for the unemployment insurance provisions in that bill). It was defeated in April by a vote of 204 to 52.23

As far as its advocates were concerned, the fight was not over. Throughout the spring and summer of 1935, the flood of endorsements did not stop. The first national convention of rank-and-file social workers endorsed it in February; the Progressive Miners of America followed, along with scores of local unions and such ethnic societies as the Italian-American Democratic Organization of New York (with 235,000 members) and the Slovak-American Political Federation of Youngstown, Ohio. Virtually identical state versions of H.R. 2827 were, or already had been, introduced in the legislatures of California, Oregon, Utah, Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and other states. Conferences of unions and fraternal organizations were called in a number of states, including the Deep South, to plan further campaigns for the Workers’ Bill. That year’s May Day was one of the largest in American history, “monster demonstrations” (to quote the New York Times) of tens of thousands taking place in New York City, for example; and in many cities, included among the marchers were united fronts of church groups, workers clubs, fraternal lodges, and Communist and Socialist groups parading under banners demanding the passage of H.R. 2827. While the majority of AFL unions never endorsed the bill, perhaps because William Green and the executive council were exerting intense pressure on them not to do so, it is probable that most of the rank and file supported it.24

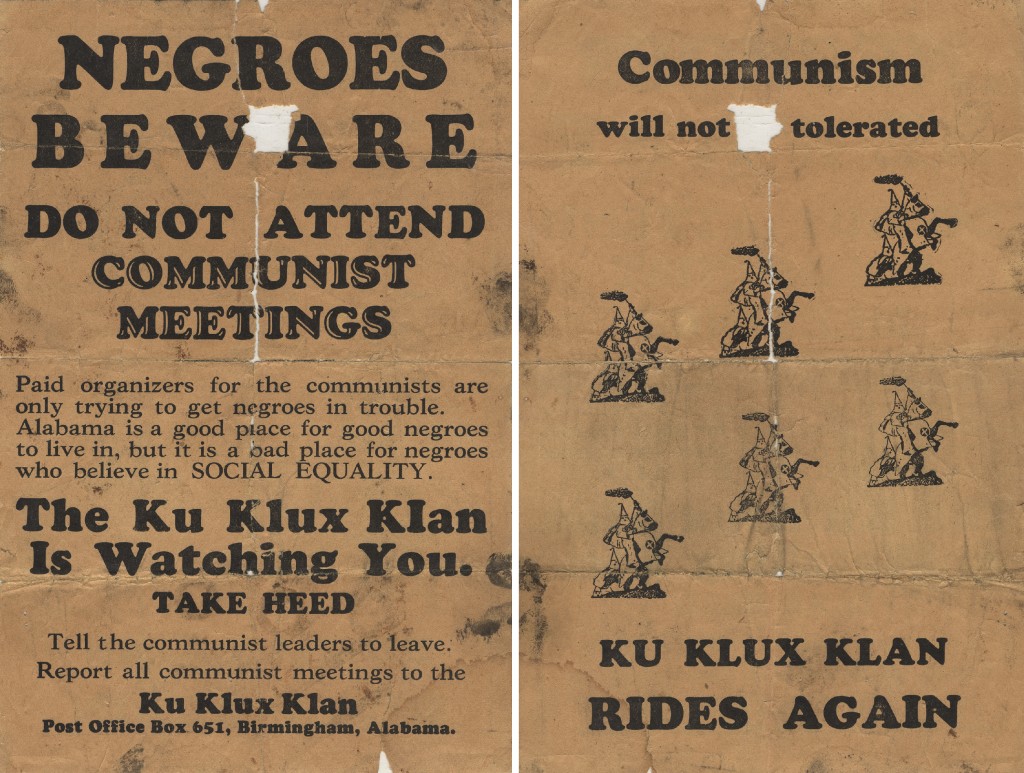

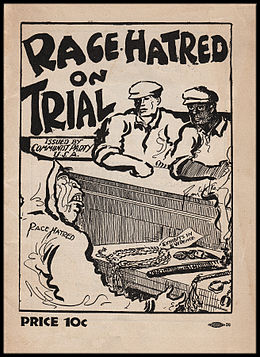

In January 1936, Ernest Lundeen and Republican Senator of North Dakota Lynn Frazier introduced in their respective houses of Congress a more sophisticated version of the bill, which the Inter-Professional Association had written. Again it was endorsed by unions, labor councils, and other institutions, including the 1936 convention of the EPIC movement in California. The National Joint Action Committee for Genuine Social Insurance, which had grown out of the 1935 Congress for Unemployment and Social Insurance, coordinated a nationwide campaign. In New York, “flying squads” from the Fraternal Federation for Social Insurance visited lodges and fraternal organizations throughout the city (e.g., Knights of Pythias, Woodmen of the World, Workmen’s Circle, etc.) to secure their support. In Philadelphia, Baltimore, and several other cities, united-front conferences and committees were organized to campaign for the bill. The hearings before the Senate Labor Committee in April resembled the hearings on H.R. 2827, with academics, social workers, unionists, and farmers testifying as to the inadequacy of the recently passed Social Security Act and the necessity of the Frazier-Lundeen Bill. A representative of the National Committee on Rural Social Planning spoke for millions of agricultural workers, sharecroppers, tenants, and small owners when he opined that this bill was “the only one which is likely to check the fascist terror now riding the fields” in the South (directed against the Southern Tenant Farmers Union).25

The fascist terror continued unchecked, however, for the bill did not even make it out of committee. After its dismal fate in 1936, it was never introduced again.

From a certain perspective, one might say that the Workers’ Bill, in its radicalism and collectivism, departed from traditions of “Americanism,” whatever that word is taken to mean. From another perspective, however, we might see the bill as something like the apotheosis of radical collectivist strains that for many decades had been embedded in American popular culture. The class solidarity it embodied in its frontal attack on fundamental institutions of capitalism—private appropriation of wealth, determination of wages by the market, maintenance of an insecure army of the unemployed—has perhaps just as much claim to the title of “Americanism” as anything else, for U.S history abounds with the solidarity of the wealthy and the solidarity of the poor. It so happens that with regard to the Workers’ Bill, as on so many other occasions, the solidarity of the wealthy triumphed—because, as always, of the greater resources at the disposal of the wealthy.

In any event, it should be clear from the foregoing discussion that the Workers’ Bill deserves more attention from historians than it has received, not only as an intrinsically interesting phenomenon but also because its popularity suggests that “ordinary Americans” in the Depression years were a good deal more radical than historiography has tended to assume. If a significant proportion of Americans favored the Workers’ Bill, to that extent they must have been quite dissatisfied by the comparative conservatism of the Roosevelt administration.

On one hand, there is much truth to Jefferson Cowie’s argument, for example, in The Great Exception, that the comparative radicalism of the New Deal moment in American political history was a result of very specific and contingent circumstances, such as the damming of the flood of immigration to the U.S. in the early 1920s. Whether people would have expressed so much support for the explicitly class-conscious Workers’ Bill in the absence of these circumstances is an open question. It is quite possible that the “labor aristocracy” of white men in particular would have shunned such a bill in the 1920s or earlier, given its premise of cross-racial and cross-ethnic class solidarity. Nor is it very likely that by the late 1940s, in a political environment of increasing conservatism, an ever-more-economically-secure working class would have expressed the same enthusiasm for the Lundeen Bill that it did during the 1930s, when radical horizons opened up and a new world briefly seemed possible.

On the other hand, I can detect no significant differences in support for the bill between races, genders, or regions of the country: women and men, white and Black, industrial worker and sharecropper, Northerner and Southerner signed petitions, attended rallies, and organized meetings to advocate for a legislative measure they saw as a final guarantee of economic security. Its promise to radically disrupt the American political economy was no bar to their advocacy; indeed, it is more apt to say that such disruption is precisely what attracted them to the measure.

The near-universality of working-class support is suggested by an unusual incident in March 1936, which may serve as a coda to the story of the Workers’ Bill. In order to advertise its liberal position on freedom of speech, CBS invited Earl Browder, General Secretary of the Communist Party, to speak for fifteen minutes (at 10:45 p.m.) on a national radio broadcast, with the understanding that he would be answered the following night by zealous anti-Communist Congressman Hamilton Fish. Browder seized the opportunity for a national spotlight and appealed to “the majority of the toiling people” to establish a national Farmer-Labor Party that would be affiliated with the Communist Party, though it “would not yet take up the full program of socialism, for which many are not yet prepared.” He even declared that Communists’ ultimate aim was to remake the U.S. “along the lines of the highly successful Soviet Union”: once they had the support of a majority of Americans, he said, “we will put that program into effect with the same firmness, the same determination, with which Washington and the founding fathers carried through the revolution that established our country, with the same thoroughness with which Lincoln abolished chattel slavery.”26

Reactions to Browder’s talk were revealing: according to both CBS and the Daily Worker, they were almost uniformly positive. CBS immediately received several hundred responses praising Browder’s talk, and the Daily Worker, whose New York address Browder had mentioned on the air, received thousands of letters. The following are representative:

Chattanooga, Tennessee: “If you could have listened to the people I know who listened to you, you would have learned that your speech did much to make them realize the importance of forming a Farmer-Labor Party. I am sure that the 15 minutes into which you put so much that is vitally important to the American people was time used to great advantage. Many people are thanking you, I know.”

Evanston, Illinois: “Just listened to your speech tonight and I think it was the truest talk I ever heard on the radio. Mr. Browder, would it not be a good thing if you would have an opportunity to talk to the people of the U.S.A. at least once a week, for 30 to 60 minutes? Let’s hear from you some more, Mr. Browder.”

Springfield, Pennsylvania: “I listened to your most interesting speech recently on the radio. I would be much pleased to receive your articles on Communism. Although I am an American Legion member I believe you are at least sincere in your teachings.”

Bricelyn, Minnesota: “Your speech came in fine and it was music to the ears of another unemployed for four years. Please send me full and complete data on your movement and send a few extra copies if you will, as I have some very interested friends—plenty of them eager to join up, as is yours truly.”

Harrold, South Dakota: “Thank you for the fine talk over the air tonight. It was good common sense and we were glad you had a chance to talk over the air and glad to hear someone who had nerve enough to speak against capitalism.”

Sparkes, Nebraska: “Would you send me 50 copies of your speech over the radio last night? I would like to give them to some of my neighbors who are all farmers.”

Arena, New York: “Although I am a young Republican (but good American citizen) I enjoyed listening to your radio speech last evening. I believe you told the truth in a convincing manner and I failed to see where you said anything dangerous to the welfare of the American people.”

Julesburg, Colorado: “Heard your talk… It was great. Would like a copy of same, also other dope on your party. It is due time we take a hand in things or there will be no United States left in a few more years. Will be looking forward for this dope and also your address.”27

In general, the main themes of the letters were questions like, “Where can I learn more about the Communist Party?”, “How can I join your Party?”, and “Where is your nearest headquarters?” Some people sent money in the hope that it would facilitate more broadcasts. The editors of the Daily Worker plaintively asked their readers, “Isn’t it time we overhauled our old horse-and-buggy methods of recruiting? While we are recruiting by ones and twos, aren’t we overlooking hundreds?” One can only imagine how many millions of people in far-flung regions would have flocked to the Communist banner had Browder and William Z. Foster been permitted the national radio audience that Huey Long and the wildly popular “radio priest” Father Coughlin were.

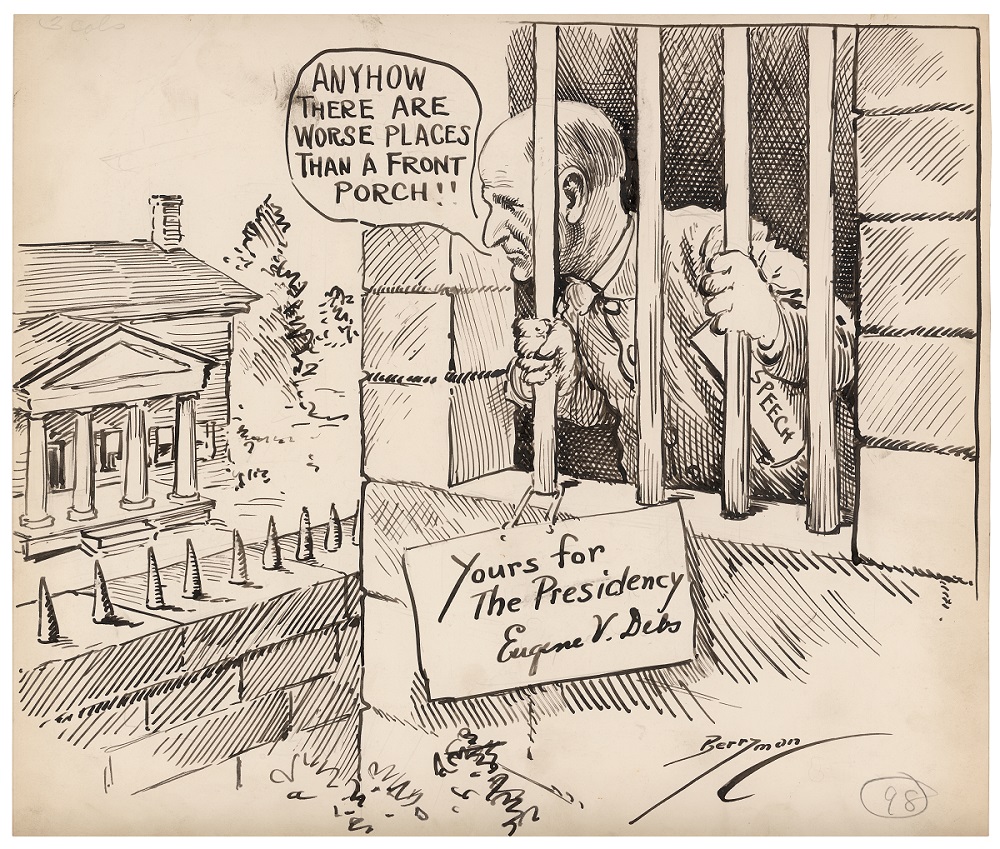

But such is the history of workers and the unemployed in the U.S.: elite efforts to suppress the political agenda and the voices of the downtrodden have all too often succeeded, thereby wiping out the memory of popular struggles. Indeed, to the extent that anti-statism and “individualism” have reigned in American political culture (as Cowie, among many others, emphasizes), it is largely because opposing tendencies and traditions have been actively suppressed, even violently crushed. But if we can resurrect such stories as that of the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill, they may prove of use in our own time of troubles, as new struggles against political oppression are born.