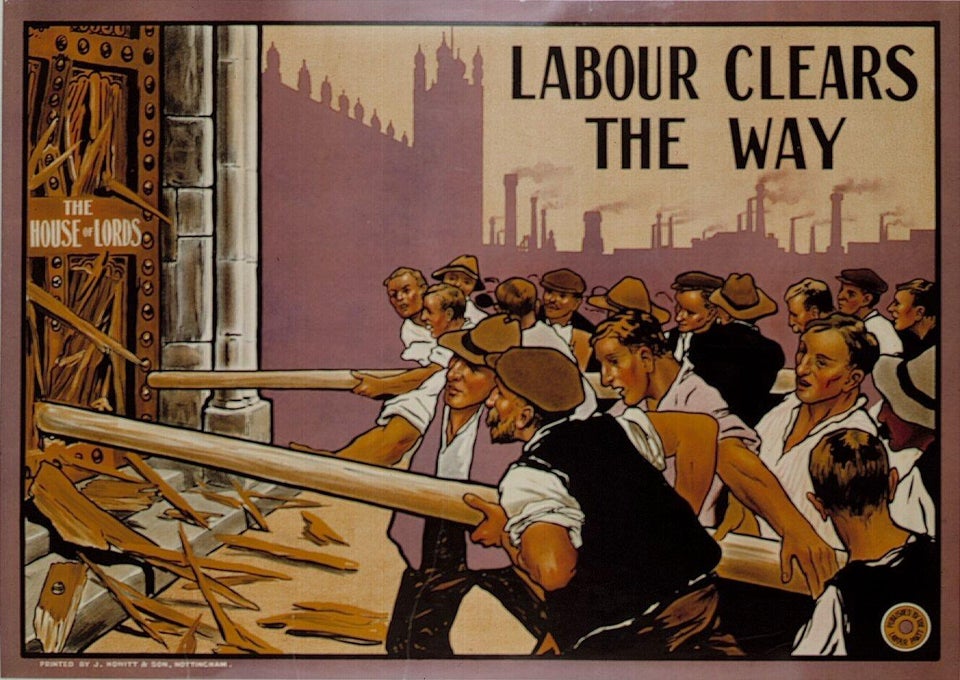

Is the UK Labour Party a possible vehicle for working-class emancipation? Alfie Hancox argues in the negative, posing the regroupment of communists independent of the Labour Party as an alternative.

‘The belief in the effective transformation of the Labour Party into an instrument of socialist policies is the most crippling of all illusions to which socialists in Britain have been prone.’

Ralph Miliband, ‘Moving On’ (1976)

Regroupment on the left

After five years of being swept up in Corbyn mania, socialists in Britain are faced with a rather dismal balance sheet. In retrospect a defining feature of the Labour left revival was its relentless draining of grassroots activist energies in the service of a permanent campaign footing, along with a collective biting of tongues while Labour councils across the country continued to implement cruel austerity measures. Corbyn’s perpetual compromises, not least on the issues of NATO imperialism and racist immigration controls, were blithely accepted on pragmatic grounds as sacrifices necessary for electoral success. A year has now passed since Labour’s general election defeat and the party’s subsequent reversion to Blairism, but parliamentary maneuvering continues to occupy center stage in socialist discourse. At a time of accelerating inequality which demands working-class unity against the capitalist onslaught, the left remains aimless and fragmented. There’s been worryingly little organized opposition to Tory wage freezes, the crackdown on trade union rights, and cuts to the health and social care sectors, which have had lethal consequences in the viral pandemic context.

There has nevertheless been some shakeup and rethinking within the radical left milieu, facilitated by the exoduses in 2013 in response to sexual violence cover-ups in the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Socialist Party (formerly Militant), as well as smaller splits from several nominally-‘Communist’ groups from 2016, in response to extreme anti-LGBTI+ attitudes (especially transphobia), national chauvinism and abuse apologia. The reconfigurations have led to networks of socialists which tend to be younger and socially progressive, committed to organizational democracy, disillusioned with the monomania of electoral ultimatums, and more attuned to the realities of working-class precarity. It is these issues that comprise the most significant fault lines within the left, rather than the old sectarian divisions inherited from the Cold War era. Among the new formations are Revolutionary Socialism in the 21st Century (rs21), formed by ex-members of the SWP, which defines itself as ‘a socialist, feminist and anti-racist organization’; Red Fightback, a non-dogmatic and intersectional communist (‘Marxist-Leninist’) group; and Anti*Capitalist Resistance (a recent merger of Socialist Resistance and Mutiny). There is also a more diffuse extra-parliamentary left including collectives organizing against carceral and border violence, small trade unions representing precarious workers and migrants, and organizations in the autonomist and left-communist traditions like Angry Workers of the World.

In the immediate term, there is thus a need to crystallize through dialogue and pragmatic organizational unity a forward-thinking revolutionary socialist movement, rather than endlessly seeking, from a position of relative weakness, diplomatic fronts with reformist leaders in which political differences are submerged. The last thing that’s needed is more of the ramshackle broad left coalitions (the Socialist Labour Party, Respect, Socialist Alliance, Left Unity etc.) which have invariably sought to ‘replace New Labourism with one or another version of old Labourism.’ Conversely, attempting to construct in splendid isolation new ‘vanguard parties’, based on fetishized notions of ideological unity in lieu of mass roots, will simply reproduce the old harmful patterns of sectarianism, abuse, and political irrelevancy. There may be scope for the progressive socialist networks to coalesce around a minimum revolutionary programme, purposefully differentiated from the moderate state-capitalist policies of the Labour left – i.e., a reassertion of the traditional communist united front approach.

In North America, the Marxist Center ‘base building’ initiative, for all its limitations (some of which are discussed below), has succeeded in bringing together socialists from an unprecedented number of tendencies, and represents ‘a serious commitment to centering revolutionary praxis above leftist infighting and bickering.’ The embryonic British Marxist Centre should aspire to fulfil a similar function. It can draw inspiration from the example of the foundation of the original Communist Party of Great Britain one hundred years ago, which brought together surprisingly divergent forces including syndicalists, ‘left communists’, anti-colonial militants and British Bolsheviks, with the shared aim of approaching a critical mass of committed revolutionaries necessary to have a qualitative impact on the class balance of forces in the country. As Sai Englert stresses in his thoughtful ‘Notes on Organisation’, any attempted construction of a new socialist unity must simultaneously acknowledge ‘that rejecting the old divisions that have plagued the socialist left will not make important political differences disappear … the aim should be to achieve practical unity wherever possible, while maintaining political tension and disagreement.’

We’re at a historical flashpoint with world capitalism slipping ever deeper into systemic crisis, which makes it all the more pressing to re-establish a strategic orientation towards building counter-power and planting deep roots in working-class communities, rather than hedging all our bets on the next election cycle. Conceptual clarity on the specific nature and role of the ‘left-wing’ of reformism is critical, in light of the organizational setbacks that occurred during the Corbyn years. The euphoria at the surprise 2015 breach in the neoliberal status quo meant there was no sober assessment of the politics of the Labour left, and the moderating role it has historically played in relation to working-class struggle. Of specific relevance for the Marxist Centre project, it is also important to avoid the temptation of viewing community organizing as in itself some kind of shortcut out of the pitfalls of gradualism and opportunism. Political lines of demarcation remain necessary to prevent base building from becoming just another avenue of front work for reformist politicians, a problem which has arisen in the US context in relation to the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA).

The terminal sickness of Labourism

Decades of normalized despair under neoliberal hegemony blindsided the extra-parliamentary left to the treachery of social democracy, or what the New Left theorist Ralph Miliband referred to as the ‘sickness of Labourism’.1 As Carson Rainham notes in The Lever, ‘the energy poured into the Labour Party since 2015 by the radical and liberal Left felt necessary but only because it arose from the desperate state of the left-wing politics in Britain which still lacks any semblance of political power or organisational method.’ The ‘cult of non-personality’ that grew around Corbyn obscured how he was propelled to the Labour leadership upon a groundswell of existing anti-austerity sentiment, which was subsequently demobilized by being redirected into electoralism. Even Plan C, a libertarian-communist organization, ended up encouraging its supporters to cast their votes for old Labour-style state ‘socialism’. The myopic obsession with parliamentary activity lingers on, with groups like Socialist Appeal calling for continued agitation inside Labour to get Corbyn reinstated as an MP. The prevailing view that we must abstain from criticizing Corbynism for fear of strengthening the Labour right is precisely the outlook that maintains the British left’s eternal farce, of assuming the end goal of a ‘socialist’ Labour government justifies the most self-defeating means: permanent class collaborationism, equivocations and lesser evil-ism, betrayal of proletarian internationalism, and the erasure of ‘left’ reformists’ longstanding occupation as unwitting agents of the ruling class.

We need to be clear that Labour has never been a ‘centrist’ party like the German Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), straddling a line between reform and revolution. Lenin correctly recognized Labour as a ‘thoroughly bourgeois party, because, although made up of workers, it is led by reactionaries, and the worst kind of reactionaries at that, who act quite in the spirit of the bourgeoisie’. A common mistake among British Marxists is to extrapolate Lenin’s point in “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder about the need for communists to agitate within conservative trade unions – which entails combating ‘spontaneous’ economism and sectionalism – as applicable to engagement with reformist political parties. Trade union officials are at one remove from the immediate class struggle, and under pressure from the rank-and-file can be forced leftwards and sometimes even be brought into confrontation with Labour governments (as during the Winter of Discontent in 1978-9). The Labour Party, however, was from its inception twice removed from struggles at the point of production.2

‘Socialist’ politicians in Labour do not represent the working class; rather they have traditionally attempted to mediate between the conservative trade union bureaucracy and the bourgeois establishment. They remain committed to class compromise under the rubric of ‘national unity’, and do not side with workers against the capitalist state – the ruling-class dictatorship – which is why, despite their frequent radical phraseology and apparent conflict with Labour’s right wing (especially when the party is in opposition), they are routinely complicit in the crushing of independent working-class action.

The Labour left is loyal firstly to the Labour Party, which is in turn loyal to capitalism. Left Labourites have no coherent ideology of their own; they live ‘in a dream-world in which block vote millions take the place of the flesh and blood millions outside the conference chamber and committee room, in which the radical policy resolution substitutes for the real struggle of class against class.’3 As Mike Macnair puts it: ‘The Labour left, to the extent that it remains within the circle of nationalism, legalism and class-collaboration, is umbilically tied to the right.’ The rapid adaption of the early Labour Party to the disciplinary operations of the bourgeois parliamentary arena effectively defanged an entire generation of radical trade union leaders. Upon being elected as Labour MPs, the Red Clydesiders who had once ‘struck terror in the hearts of the upper class’ displayed ‘but the palest reflection of that earlier militancy.’ Likewise, the Labour MP George Lansbury who made a name for himself in the early 1920s as the hero of municipal socialism, defying the punitive government attacks on poverty relief, had by 1925 put his hopes in electoral action and called off a strike by council workers.4

Marxists defending their political dependence on the Labour Party will inevitably refer to how in 1920 Lenin instructed the newly-formed British Communist Party (CPGB) to attempt to affiliate with Labour. However, this was a strictly tactical gambit, based on Lenin’s (rather questionable) assessment that Labour was still a flexible political federation, in which revolutionaries would retain ‘sufficient freedom to write that certain leaders of the Labour Party are traitors … [and] agents of the bourgeoisie in the working-class movement.’ In the ten decades since Lenin’s death, a defining feature of most ‘revolutionary’ groups in Britain laying claim to Leninist doctrine has been their replacement of Lenin’s tactical formulation with its ensemble of caveats, by a pursuit of strategic alliances with the ‘left-wing’ of (often governing) reformism, in which key political differences are submerged. Lenin had recognized the need to continually expose the brand of opportunists who ‘flaunt before the workers’ high-sounding phrases about recognizing revolution but as far as deeds are concerned go no farther than adopting a purely reformist attitude’; emphasizing how the capitalist class ‘needs hirelings who enjoy the trust of a section of the working class, whitewash and prettify the bourgeoisie with talk about the reformist path being possible, throw dust in the eyes of the people by such talk, and divert the people from revolution’. This duplicity was exemplified by the Labour pioneer (and Corbyn’s idol) Keir Hardie, a self-professed Marxist who could talk left when it suited, for instance claiming his party was ‘revolutionary in the fullest sense of the word’, while simultaneously reassuring the capitalists by stating that ‘it is a degradation of the Socialist movement to drag it down to the level of a mere struggle for supremacy between two contending factions. We don’t want “class conscious” Socialists.’

After Lenin’s death in early 1924, Leon Trotsky elaborated the analysis of ‘left-wing’ reformism in his writings on the ‘Problems of the British Labour Movement’ (1925-6). Trotsky was able to pinpoint how Labour lefts ‘reflect the lethargy of the British working class’, converting workers’ emancipatory aspirations into ‘left phrases of opposition’ that place no real obligations on the pro-capitalist reformers. He explained that the Labour left functions as ‘a sort of safety valve for the radical mood of the masses’, by channelling ‘the political feebleness of the awakening masses into an ideological mish-mash. They represent the expression of a shift but also its brake.’ This moderating role was apparent during the climax of interwar class struggle in Britain: the General Strike of 1926, in which several million workers struck for nine days, withstanding acute state repression, only to be sold out by the Labour and Trades Union Council (TUC) leaderships. While communists played a central role in the Councils of Action at the local level, the CPGB, under the direction of the Communist International (Comintern), made a crucial strategic error in failing to expose the reactionary role of the reformist leaders. This was despite the fact that the 1924 Labour administration had paved the way for the ruling-class reaction, by setting in motion the Emergency Powers Act enabling the government to use troops against workers.

The CPGB’s muted criticism of Labour was based on its desire not to alienate TUC and Labour Party ‘lefts’ like George Hicks and Albert Purcell. However, when the Labour Party headquarters spearheaded the anti-communist witch hunts in 1924-5 the foremost left-wing Labour politicians, including Hicks and Purcell, had sided with the right and backed the expulsion of CPGB members, while Lansbury denounced communist sympathizers as ‘wreckers’. It was only in the aftermath of the Strike that the communists issued a declaration pointing out that the left reformists ‘were only with the miners while it was a question of phrases and resolutions … When the crisis came they ran away.’5 The experience demonstrated that Trotsky was correct to recognize that ‘in certain circumstances, the Labour left was actually more dangerous than the out and out imperialists such as [Ramsay] MacDonald and [J.H.] Thomas in that they misled the workers, providing left cover for the right only to betray the workers equally badly when the crunch came.’ Trotsky also predicted that if the Labour left did get into power it would immediately capitulate to the right, and indeed when Lansbury inherited the Labour leadership in 1932 he pursued a policy of ‘MacDonaldism without MacDonald’, and blocked proposals that Labour-controlled councils refuse to enforce the draconian Means Test on unemployment relief.6

It must be said, however, that in subsequent years Trotsky’s analysis of Labour became rather confused. His politics were overdetermined by his break with the Comintern, after which he often mirrored its policy vacillations. During the Third Period (1928-35) when the Comintern’s foreign policy veered sharply to the left, Trotsky lurched in the other direction and eventually began claiming Labour was not a ‘bourgeois labour party’ (as Lenin argued) but ‘a workers’ party’ which should be ‘critically supported’ (including against the Communist Party!) because, unlike the governing Tories, it ‘represented the working class masses’.7 Trotsky also, like Lenin, harboured millenarian expectations that a general crisis of capitalism would engender the rapid demise of reformism, and as early as 1926 he claimed that ‘Much less time will be needed to turn the Labour Party into a revolutionary one than was necessary to create it’ – in hindsight a ludicrous statement that has nevertheless been seized upon by Trotskyist advocates of ‘entryism’ in Labour like Rob Sewell. Typically, the surviving Labourphilic Trotskyist parties today produce very selective agitational materials omitting ‘any of Trotsky’s extremely sharp polemics with his supporters on when to leave reformist organizations and of the opportunism of those who did not.’

The lack of conceptual clarity on the nature of reformism expressed by both the post-Lenin Comintern and Trotsky has contributed to endless confusion about the true role of the Labour left. The existing Communist Party of Britain (a splinter group that survived the original CPGB’s self-liquidation in 1991) laments the historical ‘predominance of the social-democratic trend over the socialist trend’ within Labour, with the latter supposedly being hostile to monopoly capitalism.8 Likewise, Socialist Appeal, a successor to the Militant Tendency, states there are ‘two Labour parties’ and that ‘The Labour Party’s right-wing always considered the Marxist left a threat to their pro-capitalist policies … It is no accident that Stafford Cripps [one of the founders of Tribune] was expelled at the Labour Party conference in 1938, and Aneurin Bevan had the whip withdrawn’. The reality of this supposed ‘Marxist left’ was less than heroic. Immediately after the Second World War the new Labour government-imposed wage constraints and efficiency measures in the nationalised industries, provoking a series of industrial disputes. From 1945-51, Labour declared two states emergency and on 18 different occasions deployed troops to take over strikers’ jobs. In secret, the government also revived the Supply and Transport Organisation, used two decades earlier to undermine the General Strike, with the active involvement of prominent ‘left wingers’ including both Cripps and Bevan, who sat on the Ministerial Emergencies Committee in 1945, and was briefly Minister of Labour in 1951. Even the champion of ‘democratic socialism’, Tony Benn, oversaw the closure of 48 power stations in defiance of the National Union of Mineworkers when he was Energy Minister in 1977-6 (he also signed a deal to extract uranium from apartheid-ruled Namibia).9 When it comes to the treachery of reformists it is useless to talk of ‘betrayal’. As the above historical overview has demonstrated, when it comes down to the crunch even the most ‘left-wing’ Labour leaders will sacrifice the working class on the altar of ‘party unity’ or ‘the national interest’.

Miliband once observed that ‘people on the left who have set out with the intention of transforming the Labour Party have more often than not ended up being transformed by it’. For example, the post-war Communist Party dropped its programme for working-class revolution in favor of seeking ‘progressive’ parliamentary coalitions, and by the 1970s it had relegated its role to that of a think tank for the class-collaborationist policies associated with the Labour left’s ‘Alternative Economic Strategy’. Another extreme example of adaptation to reformism was the entryist Militant Tendency, which pursued a ‘legal revolution’ in the form of full nationalization. Entryism was born in the 1930s as a pragmatic response to the extreme weakness of Trotsky’s supporters vis-à-vis both communist and centrist parties in Europe. It was only meant to be a temporary measure carried out until the Trotskyists found their feet, although a desperate Trotsky certainly exaggerated the prospects for success. In its pursuance of ‘deep entryism’, Militant became politically indistinguishable from the Labour left whose coattails it clung to, and infamously wound up condemning oppressed communities fighting the police and army in the north of Ireland and Britain’s inner cities. As Trotsky put it, ‘even in the minds of “socialists” the fetishism of bourgeois legality [forms] that ideal inner policeman.’

A more subtle approach to Labour was pursued by the Socialist Workers Party, which adopted an ‘open party’ perspective that in theory preserved its political independence. However, the SWP’s economistic obsession with ‘workers’ self-activity’, inherited from its early pre-party years, created a tendency to gloss over ‘the political problem of how to break the hold that Labourism has over workers, and implies that bigger and better strikes and demonstrations alone will provide the solution to the question of working-class consciousness.’10 The SWP’s permanent slogan ‘vote Labour without illusions’ is rather more passive than Lenin’s call to support Labour ‘as a rope supports a hanging man’ (or the communist Tommy Jackson’s promise to take Labour leaders by the hand ‘as a preliminary to taking them by the throat’). In practice, the SWP has sought endless broad fronts with Labour lefts (e.g. the Anti-Nazi League and Stop the War Coalition) in which its approach is to ‘fudge differences by diplomatic agreement to windy generalities, [or] self-censor and thereby pretend that there is more agreement than there actually is.’ Donald Parkinson identifies a similar trend in North America in relation to joint campaigns between Leninist groups like the Party for Socialism and Liberation, and the reformist Democratic Socialists. Likewise, one of the founders of the US Marxist Center has complained of a tendency among the affiliated organisations to ‘just focus on local shit’ and avoid political struggle against the hapless left-liberal leaders of the DSA.11

There is of course still a need for socialists to have some engagement with mass reformist organisations, and we can’t ignore the fact that Labour ‘could recruit hundreds of thousands of working-class members over a period of five years without ever turning these into active members’. But any such engagement must be aimed at crystallizing, not diluting, an unofficial Left Wing movement opposed to the social-democratic opportunism of the scab ‘soft’ left leaders like Corbyn and McDonnell. As Trotsky explained, ‘One must seek a way to the reformist masses not through the favor of their leaders, but against the leaders, because opportunist leaders represent not the masses but merely their backwardness, their servile instincts and, finally, their confusion.’ It is a shame that British Trotskyists have generally failed to heed their prophet’s own sound advice, that: ‘The Communist Party can prepare itself for the leading role only by a ruthless criticism of all the leading staff of the British labour movement and only by a day-to-day exposure of its conservative, anti-proletarian, imperialist, monarchist and lackeyish role in all spheres of social life and the class movement.’

Five wasted years

Since 2015, the left has been hamstrung by its failure to recall the painful lessons learned under old Labour. Corbyn’s ‘radicalism’ was severely overstated by both supporters and detractors, given that Labour had won office on more left-wing platforms in the 1970s. Corbynomics essentially presented a programme for capitalist growth based on technological innovation, with John McDonnell invoking ‘the Entrepreneurial State’ and ‘socialism with an iPad’. McDonnell quickly dropped his initial talk of nationalizing all the main banks, in favor of ‘people’s quantitative easing’ through a single state investment bank which, as Marxist economist Michael Roberts points out, is hardly extreme when there is already a European Investment Bank, a Nordic Investment Bank and many others, ‘all capitalised by states or groups of states for the purpose of financing mandated projects by borrowing in the capital markets’. McDonnell’s industrial strategy took its lead from ‘such uncompromisingly capitalist regimes as Singapore, South Korea, Japan – and most of all, the United States.’12 In any case state ownership does not amount to workers’ control, and neither does putting a few workers on company boards to involve them in the planning of their own exploitation.

Throughout the Labour Party’s history, a reinvigorated left-wing has served the function of successfully drawing disillusioned radicals back into the party’s orbit. To many ‘revolutionary’ socialists, the Labour left appears as a ‘bridge’ to the party’s rank-and-file; but as Miliband wrote the bridge ‘does not, so to speak, open out leftwards but rightwards’. The Bevanite politician Richard Crossman admitted the illusory character of democratic pressure on Labour, explaining how the party ‘required militants, politically conscious socialists to do the work of organizing the constituencies’; hence the utility of a party constitution ‘which maintained their enthusiasm by apparently creating a full party democracy while excluding them from effective power’.13 The same drive to assimilate and defang characterized Corbynism, with its notion of creating a ‘social movement party’ or what McDonnell described as ‘going into government together’. The grassroots anti-austerity campaigns that arose post-2010 were undermined when young socialists once again flocked into a Labour Party intent on implementing cuts at the council level. Corbyn supporters mourning the ‘inexplicable’ defeat of Laura Pidcock, the ‘anti-austerity’ candidate for North West Durham, at the 2019 general election were presumably unaware that as councillor for Northumberland she voted for £36m worth of spending cuts in 2017-20. In the 1980s left-wing Labour councils at least offered some resistance with their policy of ‘three noes’ – no cuts, no rent rises, no rate rises – although they were soon enough called to heel by Neil Kinnock.

Labour appropriates and disposes of activists’ demands as proves convenient: the Labour Campaign for Free Movement poured its efforts into securing a nonbinding resolution and was subsequently ‘betrayed’ by the 2019 manifesto, as was the campaign to get Labour to commit to net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. Corbynism even reinforced the passivity of left-wing trade unions like the FBU, which re-capitulated to their traditional ‘don’t rock the boat and ruin Labour’s electoral chances’ posture. Englert notes that investing all hopes and energies into the Labour left ‘leads activists all around us to pessimisms, demobilization, and/or – much worse – a moralistic sense of superiority that dismisses the very people on which the success of our struggles depends, as inherently reactionary, backward, or unorganizable.’ This accounts for the emotive social media displays of Labour canvassers lashing out at working-class voters in the wake of the December 2019 election.

The idea of a ‘democratic grassroots’ undergirding Corbynism was also frequently overstated. Momentum, led (and to a considerable extent owned) by millionaire-property developer Jon Lansman, was always relatively small, fractured and politically moderate. As Tom Blackburn writes in New Socialist, after ‘four-and-a-half years of acrid civil war, both the structures of the [Labour Party] and the political composition of the Parliamentary Labour Party remain essentially unchanged’; mirroring the failure of Benn’s Campaign for Labour Party Democracy in the 1970s, the error of which was to assume there was ever a possibility of democratization ‘in and against’ the capitalist state machine. As for the post-Lansman factions, they have all fallen into the trap of viewing ‘the causes of defeat in cultural or organizational issues, and refuse to acknowledge the real failure – a series of political errors’. The Forward Momentum splinter has committed to democratising a Labour Party in which the iron grip of Keir Starmer’s right-wing has been consolidated. As Richard Seymour points out, if what these groups want is a genuinely democratic Labour Party ‘they will be trying to bring about something that has never before existed, and which goes against all the dominant tendencies in parliamentary democracy.’14

Socialist Appeal has boldly proclaimed that ‘Corbyn’s serious mistake was not to move immediately after his election to purge the party of the right-wing Trojan horse in the parliamentary Labour Party’ – as if Corbyn (or any other left Labourite) ever possessed either the means or motivation to do so. Again, this framing is part of the eternal Labour left mythos, just like in 1988 when the Labour leadership contest between Benn and Kinnock (who paved the way for Blairism) was ‘portrayed by the bourgeois press and most of the ostensibly socialist left as a David and Goliath battle for the “socialist soul” of the party’ – upon his narrow defeat Benn and his followers of course immediately called for ‘unity’ with the right. Similar conciliatory attitudes were expressed by left-wing MPs when Corbyn was suspended in October by the Labour leadership, for pointing out the political motives underlying many of the allegations in the EHRC anti-Semitism report. McDonnell called Corbyn’s suspension ‘profoundly wrong’, but cravenly added that ‘my appeal is not the launch of some civil war or for members to leave the party … My appeal is for unity.’ Dianne Abbott likewise affirmed that ‘the priority right now for everyone in our party is to come together’, while another eminent Socialist Campaign Group MP, Nadia Whittome, stated she ‘cannot agree’ with Corbyn’s stance.

Right-wing witch hunts date from Labour’s earliest days, initially targeting CPGB members. Cripps and Bevan were both kicked out in 1939 for advocating a Popular Front with the communists; however they soon gained readmission after agreeing ‘to refrain from conducting or taking part in campaigns in opposition to the declared policy of the Party.’ In 1961 Michael Foot was expelled from the Parliamentary Labour Party when he rebelled over air force spending, but two decades later, as Labour leader, he embraced NATO and backed Thatcher’s imperialist war in the Falklands. Corbyn himself has now put out a grovelling statement pledging to ‘fully support Keir Starmer’s decision to accept all the EHRC recommendations’ and to ‘do what [he] can to help the Party move on … and unite to oppose and defeat this deeply damaging Conservative government.’ Obviously, even the soft left should be defended against the forces of overt reaction – since as Trotsky noted, the ruling class’s fear is that ‘behind the mock-heroic threats’ of reformist leaders there ‘lies concealed a real danger from the deeply stirring proletarian masses.’ But at the same time we are not obliged to cover for reformists’ opportunist vacillations and self-delusions, which only helps them maintain their parasitic vice over the more politically-conscious sections of the working class.

All this is not to argue that anti-electoralism should be made into a dogma. Under certain conditions, the parliamentary arena can be weaponized by socialists for agitational purposes, as with Karl Liebknecht’s heroic stand against the imperialist First World War in the German Reichstag; or the fiery House of Commons speeches by the British communist MP Shapurji Saklatvala, condemning Labour’s ‘enlightened’ colonial policy. However in general when it comes to electoral work, the Comintern’s guidelines laid down at its Second Congress remain applicable, namely that communist MPs must ‘subordinate all their parliamentary work to the extra-parliamentary work of their Party’; and must not only expose the bourgeoisie, but also ‘systematically and relentlessly’ expose reformists and centrists – communist MPs are principally agitators ‘in the enemy camp’. The socialist movement firstly needs its own infrastructure and political independence, in order to be able to engage with reformists from a position of relative strength. As Macnair summarises:

‘Marxists, who wish to oppose the present state rather than to manage it loyally, can then only be in partial unity with the loyalist [i.e. reformist] wing of the workers’ movement. We can bloc with them on particular issues. We can and will take membership in parties and organisations they control – and violate their constitutional rules and discipline – in order to fight their politics. But we have to organise ourselves independently of them. That means that we need our own press, finances, leadership committees, conferences, branches and other organisations.’

Counter-power and the long revolution

The revolutionary left in Britain has lost its nerve and its capacity for strategic thinking.

Intensifying inter-imperialist antagonisms and the climate crisis ensure an existential sense of urgency, but we can’t lose our heads and seek out revolutionary shortcuts, as happened with the Comintern in the turbulent years between the world wars. The economic conditions that enabled the ‘golden era’ of social-democratic ascendency are a relic of the past, but reformist consciousness does not mechanically disappear. Trotsky, in one of his more sober insights, noted of crisis-ridden Britain in the 1930s that ‘the political superstructure of this arch-conservative country extraordinarily lags behind the changes in its economic basis.’ Political tactics must be appropriate to the particular national conjuncture of class struggle. As against the CPGB’s Popular Front policy, Trotsky recognised that pursuing diplomatic unity with ‘progressive’ reformists and liberals as a preventative against fascisation was an absurdity that only weakened the position of the British working class, at a time of sharpening social antagonisms. The arrival of classical fascism is only possible after a ‘decisive victory of the bourgeoisie over the working class’, as in Italy and Germany; but ‘the great struggles in Britain [were] not behind us, rather ahead of us.’ In a context like today in which the fascist danger is ‘still in the third or fourth stage away’, Trotsky rightly argued that:

‘British reformism is the main hindrance now to the liberation [of the British proletariat] … The policy of a united front with reformists is obligatory but it is of necessity limited to partial tasks, especially to defensive struggles. There can be no thought of making the socialist revolution in a united front with reformist organizations. The principal task of a revolutionary party consists in freeing the working class from the influence of reformism.’

This is why uncritically supporting Corbyn at all costs as a path of lesser evil in the face of Tory savagery was self-defeating. Our strategic outlook should be that which would’ve been most appropriate for the CPGB in the post-1926 period of revolutionary downturn, namely a ‘practice based on attempting to build a solid, stable core of revolutionaries with an eye more for the horizon than for the next strike’ (or election cycle).15 Lenin explained how Bolshevik success in toppling Tsardom in 1917 owed to the fact that for many years legal and illegal networks and structures were ‘systematically built up to direct demonstrations and strikes’. The problem is that in Britain today the culture and infrastructure of working-class resistance has been completely hollowed out, and needs to be rebuilt from the ground up.

The idea of socialists getting rooted in working-class communities is of course not novel. The CPGB in the 1920s-30s managed to establish ‘Little Moscows’ in mining towns such as West Fife, Rhondda and the Vale of Leven: ‘The local Communist parties of these industrial villages were deeply integrated with every aspect of the community’s social life and culture as well as exercising their strengths in the workplace.’16 Agitation around wages, poor relief, and housing was coupled with the creation of red schools, sports leagues, and even music bands. There are a number of avenues today for building ‘dual power’ alongside the existing capitalist state, such as shop-floor committees, mutual aid societies, educational groups, trade and tenant unions, various anti-austerity campaigns, and migrant support networks. It’s also encouraging to see the emergence of new communist publications committed to producing analysis and theory that transcends the ossified twentieth-century dogmas of ‘official’ Marxism-Leninism, including Ebb Magazine, Cosmonaut, and The Lever. Dual power strategy should further address the role of working people’s councils at the district level. The surviving ‘Leninist’ parties in Britain have largely forgotten the need for independent working-class self-organisation capable of displacing the capitalist state machine, amounting to a paradoxical situation of ‘Bolsheviks without soviets’.

While the necessarily protracted nature of building counter-power is clear, this does not imply a return to the pre-1917 Kautskyan gradualism that is currently being promoted by Marxist theorists in the DSA including Eric Blanc. For ‘democratic socialists’ like Blanc, the state itself is seen as a zone of class struggle autonomous of capitalism. Teresa Kalisz of Red Bloom, another US Marxist Center affiliate, has also recently advocated a path between social democracy and revolutionary insurrection by drawing on the writings of the late E.O. Wright, who called for socialists to ‘control the capitalist state apparatus (or at least parts of it) and to use that apparatus systematically in the attack on capitalist state power itself.’17 The problem with this argument is that once within the existing state machinery, political organisations (like Labour) are ‘bound by thousands of threads’ to the dictates of capital accumulation and the reactionary governing bureaucracy, as the entire history of democratic socialism in practice has demonstrated. And behind the trappings of bourgeois parliament and the entrenched state bureaucracy as the first line of defense against working-class insurgency, there still stand the forces of the courts, police, and military – ‘the “bodies of armed men” which guarantee the power of the state whichever government is nominally in office.’18 The capitalists will never willingly give up power, and as Sophia Burns puts it socialism ‘isn’t a gradual process where reforms (or mutualist co-ops!) stack on top of each other until one morning, you wake up to find that capitalism is gone.’ There remains the inescapable question of the point of total rupture, or insurrection, beyond dual power to the replacement of the capitalist dictatorship with a workers’ government.

As capitalist violence is centralized through the state and cannot just be dismantled at the local level, there is still a need for some kind of general revolutionary (i.e. not broad left) organization on a national basis – an independent workers’ party. The American Marxist Center provides a useful model in bringing regionally-dispersed dual power initiatives together in a shared network, and enabling socialists of various leanings to begin to identify strategic points of unity. Ideally the British MC, in addition to foregrounding practical alternatives to parliamentary canvassing, will similarly function as a political centre that encourages dialogue between existing progressive tendencies. There is a pressing need to work towards a new socialist unity in diversity, in contrast to the ideological uniformity of the old sects. As Parkinson and Parker McQueeney have argued in the US context:

‘A party is simply an organization of political actors organized around a certain strategy and vision for change: a program. It is essential that the Marxist Center does not become another micro-sect that clings to a certain theoretical vision of Marxism with a priori shibboleths that define the group’s politics, whether Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyist, left-communist, etc. The organization must be internally democratic and oriented towards building working class political power independent from the bourgeois parties. Without this, any debates over the correct political line, while potentially useful intellectual exercises, will be effectively pointless.’

As suggested in the beginning of this article, there is in Britain a socialism that is dying and a socialism that must be reborn. In the first instance, however, this necessary regenerative process can only materialise through the recognition that the bourgeois Labour Party – ‘left’ flank included – never was and never will be anything but a brake on working-class liberation. The rupture in the oppressive logic of capitalist realism which 2015 heralded was of course itself extremely significant, and as the editorial collective of The Lever state:

‘Our task now, is not to let the dreams of emancipation which fuelled the Corbyn movement wither in defeat. We must steel ourselves, and divert these energies into building real counter-power, into long term revolutionary institutions, to re-build a base for an emancipatory politics, and one that can be lead into a revolutionary confrontation with the current system.’