In a comparative study of Austro-Marxism, the French Socialist movement, and Bolshevism, Medway Baker argues for the left to seek unity around a programme of constitutional disloyalty.

What does party-building look like? This has been a topic of great contention in the past months and years, especially as conflicts within and about the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) come to the fore, and as a “base-building” tendency has begun to develop on the left, most notably around the Marxist Center organization (MC). That this question is once again on the left’s radar is a sign of organizational and intellectual resurgence in our ranks, and this must be celebrated. But in the process of these debates, misconceptions have been propagating, in large part because of the linguistic baggage inherited from various traditions: “dual power”, “base-building”, “cadre formation”, “mass work”, and much more.

These terminological debates, although sometimes useful, often obscure the core issues at hand. In an article published by Regeneration (MC’s publication), Comrade JC counterposes “mass work” to “base-building”, proposes the “creation of autonomous mass organizations capable of collective action to further class power”, and claims that programmatic unity “amounts to a return to… blind-alley sectarianism”. JC, mischaracterizing the concept of programmatic unity, asserts that “for a socialist intelligentsia largely cut off from the wider working class and lacking meaningful structures of counter-power, programmatic unity puts the cart before the horse.” JC’s solution is “cadre formation through mass work”—a nice-sounding phrase, but hardly a new idea. This is simply base-building elevated to a strategy, retheorized with a more Marxist-sounding phraseology.1

As I have argued previously, we must be clear about revolutionary strategy if we are to build a communist party.2 This means that a party in formation, even before attaining a mass base, must be built on the basis of a programme. “Cadre formation through mass work” is itself the process of party-building, and unity within and between cadres can only be forged on the basis of a shared programme. A party without a programme is no party at all, and a cadre without a party can never hope to win the proletariat’s confidence and take power.

So the question remains unanswered: What does party-building look like? What does “unity” mean, and how can we transcend the theoretical unity model of the microsects? We will explore these questions by comparing the “fanaticism for unity”3 exemplified by the Austrian Social-Democrats, the debates within French Socialism surrounding prospects for unification with the Communists, and the Bolsheviks’ conduct towards other socialist parties during the October Revolution. We will find that programmatic unity can and must be found through comradely debate and shared struggles, and that unity must be constructed on a shared basis of disloyalty toward the bourgeois constitutional order and democratic centralism: freedom of debate combined with unity in action.

According to Otto Bauer, a leading member of Austrian Social-Democracy’s left-wing, Austro-Marxism “is the product of unity… [and] an intellectual force which maintains unity…. [It] is nothing but the ideology of unity of the workers’ movement!”4 Drawing on the course of the Second International’s split, he explains:

“Where the working class is divided, one workers’ party embodies sober, day-to-day Realpolitik, while the other embodies the revolutionary will to attain the ultimate goal. Only where a split is avoided are sober Realpolitik and revolutionary enthusiasm united in one spirit…. The synthesis of the realistic sense of the workers’ movement with the idealistic ardour for socialism… protects us from division…. It is more than a matter of tactics that we always formulate policies which bring together all sections of the working class; that we can only get unity, the highest good, by combining sober realism with revolutionary enthusiasm. This is not a tactical question, it is the principle of class struggle…”5

Bauer clearly bends the stick too far towards unity at any cost. Unity with the sorts of reformist social-traitors who urged workers to war and drowned popular revolts in blood (such as the Ebert government in revolutionary Germany) is neither desirable nor possible. But this must be understood in the context of Austrian Social-Democracy, which—while it failed to offer any opposition to the imperialist war of 1914-18, and should be critiqued for this—was not nearly as bankrupt as German Social-Democracy. The Party initially did support the war effort on defencist grounds—defense of the Austrian proletariat from Russian autocracy—but upon coming to power in the aftermath of the war, the Social-Democrats did not turn the repressive apparatus of the state against the proletariat, but rather sought to neutralize the state’s repressive capacity.6 Bauer analyzed the early Austrian Republic as a state “in which neither the bourgeoisie nor the proletariat could [rule], both had to divide the power between them.”7 Further, the Austrian Republic’s Social-Democratic government was one of the few to recognize and trade with the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919.8 We should critique the Austrian Social-Democrats for their timidity and avoidance of using force when given the opportunity (Bauer himself would later do just this)9, but we cannot say that they took an openly counterrevolutionary position when revolution came to Austria and actively sided with the bourgeoisie against the proletariat.

Bauer himself made just such an argument in late 1917 when the left-wing of the Party (to which he then belonged) was agitating for a split. He impressed upon his cothinkers that “such a division would be justified only if the majority of the party were in a position to make compromises with the bourgeois elements of the state. Given such a condition, an independent socialist body might exist to prevent reformism.”10 Bauer argued that such conditions were present in Germany—thus justifying the split of the Independent Social-Democrats (USPD)—but not present in Austria. This raises the question of what actions constitute such collaboration with the bourgeoisie, and why support for the imperialist war does not fulfil this condition; perhaps Bauer was more narrowly concerned with ministerialism and direct attacks on the proletariat, or perhaps it can be explained simply by the fact that he himself failed to oppose the war at the decisive moment and did not want to indict himself.11 However, the extent to which this stance constituted cynical opportunism can and has been argued elsewhere, and is not relevant for our purposes.

Friedrich Adler, who—unlike Bauer—opposed the war from the very beginning, nevertheless took a parallel stance. He wrote, only several months before his assassination of the Austrian Minister-President:

“All party activity consists in common action toward the realization of the party program. Every individual act rests on the majority decision of a solidary community. Two dangers threaten the party, one from the side of the majority and one from the side of the minority. The majority is always in danger that its decision does not correspond to the party program, that it contradicts the basic principles of the whole movement which it represents, the principles that give the party meaning. The minority is in danger of destroying the community of action, of not complementing the majority, of going its own way and thereby disturbs the majority decision.”12

In essence, Friedrich Adler believed that even when the majority violated the party’s programmatic unity, it was the duty of the minority to correct the movement’s faulty course by way of both inner-party struggle and independent agitation among the working class13; to be, in essence, an opposition within the party that fought against the sins of the majority while remaining loyal to the party itself. This is a shakier justification than Bauer’s, as Adler fails to define a circumstance under which a split might be acceptable. It is, however, consistent with Adler’s personal relationship to the Party, and should be understood in that context.14 It should also be noted that Adler was a political thinker of less depth and breadth than Bauer, and was not as enmeshed in the practicalities of Party and state politics during this period as Bauer and other Austro-Marxists were.

In summation, these leftist Austrian Social-Democrats believed that unity of the workers’ movement was essential, even if it meant remaining in a party that violated its own revolutionary (or at least anti-reformist) programme. They are unable to define which conditions would justify a split, outside of vague platitudes. Bauer provides a well-reasoned argument as to why this unity is so important, but he has no answer to the challenge of overcoming reformism. We will see later his failed attempts to rectify this problem following the triumph of fascist counter-revolution in Austria.

If Austro-Marxism was the “ideology of unity” in practice, then French Socialism saw unity as an essential aspiration which was to be actively pursued. Similarly to Austrian and German Social-Democracy, the French Socialist movement coalesced into a single party throughout the end of the 19th and the dawn of the 20th century, emerging in the form of the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) in 1905. It would be sundered in two only 15 years later, with the foundation of the French Communist Party (PCF). More than the Austrian Social-Democrats, the French left-Socialists not only strove to maintain unity within the Party, but also actively sought unity in action and even reunification with the Communist Party. Before moving on to a discussion of reunification efforts between the two workers’ parties, however, it is useful to discuss what unity meant to the SFIO in the first place: on what basis did the French Socialist movement first unify, and what were the outcomes?

There were several currents which merged into the Party in 1905, but the two most prominent were Guesdism15(named for the political leader Jules Guesde, who was credited with introducing Marxism to France) and Jauressianism (named for the leader Jean Jaurès, a reformist who supported alliances with the bourgeoisie16). The dynamics of these currents and others are not interesting for our purposes, but the manner in which they unified is.

The Guesdists had the majority at the unification congress, but according to Claude Willard, the foremost historian of Guesdism, it was a “deceptive victory”.17 The programme around which the Party united rejected reformism (although not reforms) and declared its irreconcilable opposition to the bourgeoisie and its state, and proclaimed a “party of class struggle and revolution.” But this was a false programmatic unity: the party apparatus was too decentralised to enforce party discipline, and in practice the programme was violated both by local party organisations and by Socialist parliamentarians. In addition, the “tendencies” inside the Party were essentially “parties within the Party”; Willard notes that “the SFIO, more than a merger, [was] the affixation of assorted ideological and political currents.”18

The existence of factions within a party is, of course, a sign of healthy discourse, which is necessary for a workers’ party to adapt to changing circumstances and remain in constant contact with the workers’ movement in all its diversity. However, for a workers’ party to present a consistent opposition to bourgeois rule and ultimately take power, it must be united in action. That is to say, all sections of the workers’ party, from local cadres to parliamentarians, must conduct their activity on the basis of the party programme, which lays out the path to workers’ rule and communism. When party activists and parliamentarians flout the programme, both democracy and centralism within the party break down, and unity in any meaningful sense is impossible.

Nevertheless, even this half-unity “constitute[d] a pole of attraction for those who had been repelled by the internecine wars between socialists”: by 1914, the Party’s membership had nearly tripled.19 However, much of this new membership, for one reason or another, was not committed to proletarian revolution, facilitating the Party’s reformist turn.20 When the imperialist war arrived, the Party was torn: many believed it was the duty of all classes to defend the Republic from Prussian militarism; a minority pled for peace, and a few declared the death of the International. The Russian Revolution in 1917 and the formation of the Communist International in 1919 intensified the tensions in the SFIO, and so, in 1920, the majority of delegates at the Tours Congress voted for affiliation to the Comintern and left the SFIO behind.

This was the beginning of a new era for the French workers’ movement. Not only did the entry of the Communist Party into the political arena have massive implications for France at large, but the inner dynamics of the Socialist Party itself underwent a shift. New personalities emerged into the heights of Socialist politics. Factions which had emerged in response to the war and the Russian Revolution morphed and new factions arose.

This split must not be understood as a simple split between reformists and revolutionaries. It is perhaps more accurate to understand the Tours Congress as a split within the left-wing camp.21 So what were the dynamics of this split, and of the Socialist Party left behind?

As the war dragged on and workers revolted in France and across the world, the pro-war majority began to adopt the pacifist rhetoric of the minority, although failing to take an active stance against the war.22 The advent of the Comintern, within this context, divided the Party into three general currents: the right-wing “Resisters”, who supported a continuation of the Second International and rejected the application of Bolshevik methods to Western Europe; the centrist “Reconstructors”, who also rejected the application of Bolshevism to France but defended the October Revolution, and wished to “reconstruct” a united International “with the still-useable materials of the Second and the new framework of the Third”; and the left-wing, which supported joining the Comintern without reservations (or, at least, any stated reservations).23

Léon Blum, for the Resisters, defended the SFIO’s unity on the basis of the socialist pluralism which had characterized French Socialism from 1905. He argued that the Comintern, after the Second Congress which had laid out the famous “21 Conditions” to which all member parties had to submit, was ideologically rigid and wouldn’t allow for internal factions and debate. In his famous speech to the Congress, in which he pleaded for broad proletarian unity, he proclaimed:

“Unity in the Party… has, up to today, been a synthetic unity, a harmonic unity; it was a result of all [of the Party’s] forces, and all the tendencies acted together to determine the common axis for action. It is no longer unity in this sense that you seek, it is absolute uniformity and homogeneity. You only want men in your party who are disposed, not only to act together, but to commit to thinking together: your doctrine is fixed, once and for all! Ne variatur! He who does not accept will not enter into your party; he who accepts no longer must leave.”24

Considering what Bolshevisation would entail for the PCF, Blum’s concerns may not be entirely without basis.25 The Comintern and PCF ultimately did clamp down on internal debate, driving many Communists out into a myriad of sects or back into the arms of the Socialist Party. What Blum fails to acknowledge, however, is that the SFIO’s pluralism was of a type that was unable to enforce unity in action. In practice, due to the Party’s decentralized nature, one militant might agitate for total hostility to the bourgeois state and the seizure of power by the workers, at the same time that a Socialist parliamentarian participated in a bourgeois coalition. Blum nevertheless insisted that the Party had enough bottom-up disciplinary mechanisms to guard against abuses by the leadership.26 At the same time, he defended this loose unity, on the basis that the duty of the Party was to assemble “the working class in its totality” in one party—no matter the cost:

“Begin by bringing together [the proletariat], this is your work, there is no other limit on a socialist party, in scope and in number, than the number of labourers and waged workers. Our Party has thus been a party of the broadest recruitment possible. As such, it has been a party of freedom of thought, as these two ideas are linked and one derives necessarily from the other. If you wish to group, in one party, all the labourers, all the waged workers, all the exploited people, you cannot bring them together except by simple and general formulas…. Within this [socialist] credo, this essential affirmation [of replacing capitalism with socialism], all varieties, all nuances of opinion are tolerated.”27

This view, much as Bauer’s and Adler’s, clearly bends the stick too far towards unity at any cost. It allows for the violation of the party programme by activists and parliamentarians in the name of pluralism, and attempts to reconcile revolutionaries and avowed class-collaborationists in a single party. It is clearly impossible to proceed towards the socialist aim when such fundamental strategic differences remain unresolved. However, Blum raises an important issue: How should socialists maintain an internally democratic spirit, without on the other hand allowing for the encroachment of reformism and opportunism?

This worry would later be echoed by Marceau Pivert, even as he called for unity between the Socialist and Communist Parties. Pivert was a leader of the SFIO’s “new left”, which arose in the years following the Tours Congress, as Blum reconciled with the Reconstructors and the space of a “left opposition” was left open.28 The new left was firmly opposed to compromise with the bourgeois state or the middle classes, and sought reunification with the Communists.29 It was also fundamentally committed to the principle of democracy. Pivert specified that, while he saw the formation of a “parti unique” (united party) as one of the highest priorities for the workers’ movement, the condition of such a merger was internal democracy, which “means that the sections designate their secretaries, that the federations choose their officials and their delegates, that only the national congresses will be sovereign.” Most importantly, internal democracy for Pivert meant “that all the nuances of opinion, socialist and communist, will be associated to the collective work, in conformity with majority rule; for this, currents of opinion (‘tendencies’) will have a legal existence, will participate in free investigation, in free internal critique, to the distribution of their theses among militants, and their representation will be assured at all levels of the organization, proportionally to their forces, and evaluated in the assemblies by regular polling.”

This conception of unity is still tinged by French Socialism’s traditional haphazard “affixation” of factions noted by Willard. Pivert defends this, however, on the basis that the Party majority may itself betray revolutionary politics, and in such a situation it would be necessary for the minority to act on what it believes to be right. “There are cases,” he says, “where formal discipline is not possible: when the Party refuses to rectify certain problems.”30 For example, he claims that Party members should be able to engage in direct actions against fascism or join mass organizations, against the instructions of the leadership. The question is, then: what kind of unity can there be in a party where even unity in action cannot be guaranteed?

In fact, Pivert was very concerned with unity of action; but he believed that it was the spontaneous direct action of the proletarian masses which would forge unity within the workers’ movement, rather than any precepts from above. I have dealt with the issue of spontaneism elsewhere; suffice to say, history has proven this “strategy” (or more properly, non-strategy) to be a dead end. It is true, however, that a united party of the working class cannot be forged simply through conferences of party or sect bureaucrats. Pivert believed that the starting point for unity should be open meetings between local Socialist and Communist party organizations, at which the membership could find common ground and coordinate further united action.31 A key aspect of this strategy was the formation of antifascist paramilitaries consisting of revolutionary workers.32

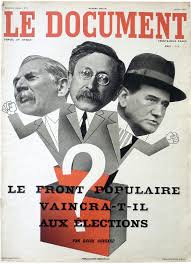

Indeed, spontaneous mass action by workers exploded across France with the election of Blum’s Popular Front government in 1936, celebrating the working class’s newfound unity (of a type).33 However, these mass actions failed to achieve “organic unity”, that is, the formation of the parti unique through the merger of the two workers’ parties. In fact, the Socialist Party bureaucracy worried that “the party was being by-passed by events”, and worked to distinguish the Socialist Party in popular imagination from the greater Popular Front movement, while combatting Communist influence in the workers’ movement. 34

Pivert fought against this tendency in the SFIO leadership and demanded that the Party encourage the creation of a cross-party antifascist paramilitary and allow members to join “popular committees”. In this way, the working class would transcend the limitations of not only each of the workers’ parties, but also of the Popular Front itself, and thus overcome their political leaderships to form a new, bottom-up proletarian unity.35 The fact that the Socialist and Communist leaders were opposed to the masses’ revolutionary impulse was irrelevant, he claimed, because “what counts is not really the supposed intention of a particular leader, but the manner in which the proletarian masses interpret their own destiny.”36The movement would be reborn with a new vitality, all types of socialist views would be tolerated, and mass action would inevitably lead the proletariat to seize power. Presumably, reformist illusions would be discarded by the masses under the pressure of events, and so undemocratic purges and discipline would not be necessary to secure the revolutionary orientation of the party.

Jean Zyromski was another leader of the new left in the French Socialist Party who was a longtime ally of Pivert’s although they diverging with the advent of the Popular Front. Zyromski admitted to being influenced by both Lenin and Bauer, among other diverse thinkers37, and was even more committed to the formation of the parti unique than Pivert. He only gave up on the endeavor in November 1937, when Georgi Dimitrov, then-head of the Comintern, demanded that the interests of the Soviet state be treated as paramount. Zyromski treated the USSR as a proletarian beachhead in the class war, which was to be defended from capitalism and fascism so that it could continue to exert pressure on the international bourgeoisie but rejected “idolatry” of the Soviet Union or the Comintern.38

Zyromski’s conception of proletarian unity was more sophisticated than Pivert’s and relied less on the spontaneity of the masses. He hoped that the synthesis of Socialism and Communism would allow the workers’ movement to transcend the limitations of each. He called for “real Unity, solid Unity, that which results from a merger of the existing Workers’ Parties, based in a Marxist synthesis of the general conceptions of the two movements of the working class…. To achieve this result,” he elaborated, “it is evidently necessary to find the points [where our programmes] intersect.”39 Against those who called for a “return to la vieille maison” (the old house—a common term for the Socialist Party, whereas the Communists belonged to the “new” house), Zyromski contested that “the destruction or liquidation of any given branch of the workers’ movement does not seem, to us, to be the path to unity. Once again, we must bring about a merger of the forces of the organized working class. This task, this merger, will be possible if the points of divergence, upon which the split was justifiably made, are reconciled in view of the facts.”40

Without denying the validity of the split at Tours, Zyromski argued that with the rise of fascism, and the USSR’s resultant shift in foreign policy, the Socialist and Communist parties had lost any real grounds for maintaining the split: both recognized the need for prioritizing antifascism, and both advocated the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat. Strategically, both parties favored the combination of legal and illegal means in the class struggle. The Popular Front was the ultimate result of this shared orientation, and although he insisted that it had no revolutionary possibilities, Zyromski believed that it could serve to combat the forces of fascism, and that a Soviet-allied France could allow the proletariat to improve its position, not through insurrectionary means, but rather through supporting a Soviet war effort against German fascism, and through combatting fascism on other fronts as well. Through pursuing these shared aims, the Popular Front might encourage the two parties to merge, as their common programmatic points and actions would trump whatever other differences remained.41

It was therefore neither “bottom-up” nor “top-down” unity that Zyromski sought, but rather organic unity brought about by unity in action, which was precipitated in turn by programmatic unity. We can thus see that programme and action are inextricable from one another, and unity on the basis of shared programmatic points is not synonymous with unity on the basis of a shared ideology.42 Rather, it constitutes unity on the basis of a shared strategy for the conquest of power, a strategy that necessarily informs present-day tactics. Programme is the immediate basis for both splits and unifications in the workers’ movement. However, Zyromski fails to propose any practical mechanism for maintaining this programmatic unity.

So we return to Otto Bauer. By this time, he had developed an idea he called “integral socialism”: a synthesis between Socialism and Communism, which would unite the positive characteristics of each while discarding their negative characteristics.

“On the one hand, we have the great mass workers’ movements: the English Labour Party, the social-democratic parties and unions of the Scandinavian countries, of Belgium, of the Netherlands, with their success, the unions of the United States, the workers’ parties of Australia—all these great mass movements are democratic and reformist. On the other hand, we have the conscious struggle for a socialist society which is realised in the USSR, the influence of which dominates the revolutionary socialist cadres of the fascist countries, makes itself felt in the mass socialist movements in France and Spain, and also in the revolutionary movement of the Far East. The link between the reformist class movement and conscious socialism, this is the problem which we must grapple with in order to devise an integral socialism.

Marx and Engels surmounted the opposition that existed between the workers’ movement and socialism in the age of bourgeois revolution. They taught the workers’ movement that its aim must be the socialist society. They taught the socialists that the socialist society could be nothing other than the result of the struggles of the working class. But the opposition between the workers’ movement and socialism could not be definitively surmounted. The unification of the movement of the working class and the struggle for a socialist society, the work of Marxism, must be redone in each phase of the development of class struggle…. Surmounting this tension which reappears ceaselessly, uniting the workers’ movement and socialism; this is the historic task of Marxism.”43

What Bauer is describing has elsewhere been termed the “merger formula”. This was no groundbreaking idea in the socialist circles which Bauer frequented. However, what he stresses is that this merger must take place on an ongoing basis, as the objective tendency of the workers’ movement is to obtain the best deal for the working class within capitalism; that is, the tendency is towards reformism, especially under bourgeois-democratic regimes.

Understanding this fact, for Bauer, is the first step towards reuniting the workers’ movement, a necessary precondition (in his view) for the defeat of fascism. He claims that the polar opposition between reform and revolution, manifested with the formation of the Comintern, was a mistake; in fact, the struggle for reforms (which is inevitable in the workers’ movement) is what will inevitably raise the class struggle to the point where only two outcomes are possible: fascist dictatorship or proletarian dictatorship. The duty of revolutionaries in the meantime, he counsels, is to support the workers’ struggles, propagate the tenets of revolutionary socialism, and organize revolutionary cadres within the workers’ movement to accomplish these goals. In addition, Marxism “must transmit to revolutionary socialism the great heritage of the struggles for democracy, the heritage of democratic socialism… [and] transmit to reformist socialism the great heritage of the proletarian revolutions…”.44

That is to say, the struggle for democracy and the struggle for the proletarian dictatorship must be united in a single party-movement in a single programme. The great split in the workers’ movement had separated these struggles into two internationals, and it was the task of true revolutionaries to reunite them. However, Bauer—much like Pivert—relies too much on the spontaneous will of the masses, which he claims will naturally progress towards revolution under the pressure of events and the influence of the revolutionaries.

Therefore neither Bauer nor Zyromski can say how it is that the workers’ party can avoid domination by reformist politics, or rebellion of reformist elements against a revolutionary programme. Zyromski comes the closest, in his advocacy of unification around shared programmatic points, while allowing for multiple factions with different theoretical bases to coexist in the same party. But he refuses to draw a definitive line which party members would not be permitted to cross. It is clear that there must be both a minimum political condition for membership in the workers’ party, and a structure which is able to ensure the application of the party’s revolutionary programme in action.

Ideological conditions—requiring that members agree with a set of theoretical tenets, such as socialism in one country, permanent revolution, protracted people’s war, or what have you—are obviously not the answer. These only serve to perpetuate the preponderance of leftist sects, which have proven themselves incapable of transforming into a mass workers’ party.

Perhaps the answer lies neither in a broad party, nor in the “party of a new type” advocated by the Comintern and inherited by the sects, but in another part of Bolshevik history: the October Revolution itself.

Contrary to popular belief, the October Revolution was not an insurrection by one party against all the rest; rather, it was a battle between the soviets and the Provisional Government for absolute authority (vlast, normally translated as “power”), in which the soviets won—thanks to the efforts of not only the Bolsheviks, but also the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries. Even those socialists who opposed the transfer of “all power to the soviets” often continued to work within the soviet state institutions, playing an active part in legislative work and frequently debating government policy in the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, or VTsIK. The government itself—the Council of People’s Commissars, or Sovnarkom—was, from December to March, a multi-party coalition, consisting of both Bolsheviks and Left SRs. But why did the Bolsheviks include the Left SRs and not the other socialist parties? What distinguished these socialists from the rest?

Lars Lih explains this in terms of “agreementism” versus “anti-agreementism”; the “agreementists” (that is, the “moderate socialists”) favored an alliance between “revolutionary democracy” (that is, the workers and peasants) and the bourgeoisie, whereas the “anti-agreementists” believed that the programme of the democratic revolution could be carried out only by revolutionary democracy, untethered from the burden of the bourgeoisie.45 This was very clearly explained before the revolution by Stalin:

“The Party declares that the only possible way of securing these [democratic] demands is to break with the capitalists, completely liquidate the bourgeois counter-revolution, and transfer power in the country to the revolutionary workers, peasants, and soldiers.”46

The fundamental message here is that in order to complete the revolution, the workers and peasants had to overthrow the Provisional Government and the constitutional order it had constructed and then replace it with their own organs of governance. The moderate socialists had betrayed the revolution, even as they claimed to defend it, because they refused to break with the bourgeois parties and declare a soviet government. The priority was not a Bolshevik government, but a soviet one, which would refuse all compromise with the bourgeoisie.

The Left SRs formulated this idea as the “dictatorship of the democracy”47, a more succinct appellation for the old Bolshevik formula of the “revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry”. The workers and peasants alone—revolutionary democracy—would exercise power, against the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie. The Left SRs actively sought to bring all socialist parties into the coalition on the basis of soviet power, and the Bolsheviks were not necessarily opposed to this goal, either (although they were not overly concerned with courting the moderate socialist parties). The debates in the VTsIK are illustrative of this:

“Kamkov, for the Left SRs: From the start the Left SRs have taken the view that the best way out of our predicament would be to form a homogenous revolutionary democratic government…. We hold to our view that the soviets are the pivot around which revolutionary democracy can unite…. If no agreement [with the moderate socialists] is reached, or if the government consists exclusively of internationalists, it will be unable to surmount the enormous difficulties facing the revolution.

“Volodarsky, for the Bolsheviks: There is scarcely anyone present here who does not want an agreement. But we cannot conclude one at any price. We cannot forget that we are obliged to defend the interests of the working class, the army, and the peasantry…. I move the following resolution:

“Considering an agreement among the socialist parties desirable, the [VTsIK] declares that such an agreement can be achieved only on the following terms:

“… 3. Recognition of the Second All-Russian Congress [of Soviets] as the sole source of authority.”48

The points of contention between the Left SR and Bolshevik positions are relatively minor; their unifying point is the primacy of the soviets, as anti-agreementist organs, which represent the workers and peasants while excluding the bourgeoisie. Their unifying point is a common revolutionary strategy of overthrowing bourgeois constitutionalism in favor of a new constitutional order, one resting on the authority of the armed masses.

Their unifying point is, in short, constitutional disloyalty. The moderate socialists’ insistence on compromise with the bourgeoisie represents a commitment, on the other hand, to playing by the rules of the bourgeois constitutional order. It is not sufficient to declare oneself a partisan of the revolution (as did many of the moderate socialists); what is necessary, for the most basic kind of unity, is a refusal to abide by the constitution.

This essential point is what drove all the coalition talks. One Left SR even proclaimed that “the government should base [its policy] on the Second Congress of Soviets. All parties that do not agree to this we consider as belonging to the counter-revolutionary camp.”49 Any party which advocated collaboration with the bourgeois parties, regardless of its stated commitment to socialism and revolution, was a liability. Lenin hinted at this in 1915, in a more raw form:

“The proletariat’s unity is its greatest weapon in the struggle for the socialist revolution. From this indisputable truth it follows just as indisputably that, when a proletarian party is joined by a considerable number of petty-bourgeois elements capable of hampering the struggle for the socialist revolution, unity with such elements is harmful and perilous to the cause of the proletariat.”50

So we must return to the issue of party unity. Although the Bolsheviks were not looking to unify with the Left SRs, the fundamental principle which drove the coalition talks remains relevant. Programmatic unity, for communists, does not mean a shared commitment to certain theoretical tenets, but rather a shared commitment to constitutional disloyalty. Only on this basis can a common programme be constructed.

The other condition, then, is structural: multiple factions (each committed to constitutional disloyalty) must be able to coexist in the same party while remaining united in action. This requires both democracy (so that each faction can be represented in proportion to its support among the membership, and each will accept the legitimacy of the central party organs’ decisions), and centralism (so that the central party organs’ decisions will be binding in fact on the actions pursued by local party organizations and by the party’s representatives in parliament). Without democracy, the party will inevitably fracture, as factions chafe under a leadership they may view as illegitimate; without centralism, the party will inevitably crumble, as unity in action breaks down. This does not mean the type of “democratic centralism” (perhaps more properly termed bureaucratic centralism) imposed by the Comintern’s “party of a new type”, which developed under the pressures of civil war and general societal breakdown in Russia. This type of centralism was hardly democratic at all, and while it may be defensible in the circumstances that the Bolshevik party found itself in, it can hardly serve as the basis for a mass workers’ party which has yet to take power—never mind a pre-party formation, which has yet to win a mass base for itself.

Programmatic unity is not an appeal for unity around theoretical tenets, nor is it an appeal for a broad left party. Both of these extremes have proven to be dead ends and it is time that we leave them behind. Communist programmatic unity means unity around a shared strategy for taking power and initiating the socialist transition, which means a shared commitment to constitutional disloyalty and pursuing multiple tactics simultaneously, all directed towards the common aim. This requires both intellectual and political pluralism and democratic centralism, which means allowing multiple factions to coexist within a single party, but acting only on the democratic decisions of the majority. In a healthy mass workers’ party, it is improbable that any one faction could hold a majority on its own, and all factions would presumably be represented in permanent party organs in proportion to their support among the membership.

In today’s context, where no such parties exist, the existing left should seek common programmatic points with each other, and unite their efforts on that basis. Adherence to a theoretical framework or opinions on the class character of various countries are not programmatic points, although they may inform certain tactics or slogans. These things, however, are things that can and should be debated, and actionable slogans should be decided through democratic deliberation, without fracturing the movement.

The starting point is not bureaucratic wrangling between sect leaderships or spontaneous mass revolts that will bypass the existing left, but rather unity in action among the left and comradely debate between communists. This is what the Communist International termed the “united front”. This does not mean glossing over theoretical, strategic, or tactical differences but rather,

“Communists should accept the discipline required for action, they must not under any conditions relinquish the right and the capacity to express… their opinion regarding the policies of all working class organisations without exception. This capacity must not be surrendered under any circumstances. While supporting the slogan of the greatest possible unity of all workers’ organisations in every practical action against the united capitalists, the Communists must not abstain from putting forward their views…”51

Through such united fronts for action—through common fights for shared aims—similar currents will be drawn together, and the memberships of various socialist and workers’ organizations will begin to move towards organizational unity. They will come to understand which issues are really important in the concrete, ongoing struggle against the capitalist onslaught, and which issues can be put to the side in day-to-day organizing. They will begin to develop a common programme, not only through theoretical debates (although these certainly hold an important place in party formation), but through mass, democratic deliberation and the practical work of organizing the working class side by side.

In short, common action around common demands will inevitably lead to a common programme. This consolidation is necessary if we wish to form a mass workers’ party. This does not mean that everyone we work with in day-to-day struggles must be a constitutional disloyalist, or that all constitutional disloyalists will choose to work alongside us; but with a true communist consolidation, both the right-opportunists and the ultraleft sectarians will be swept aside, into the dustbin of history. So let’s seek our common programme, a programme of constitutional disloyalty. The revolutionary party of proletarian unity will march forth, and its programme will bring the proletariat to power and towards communism.