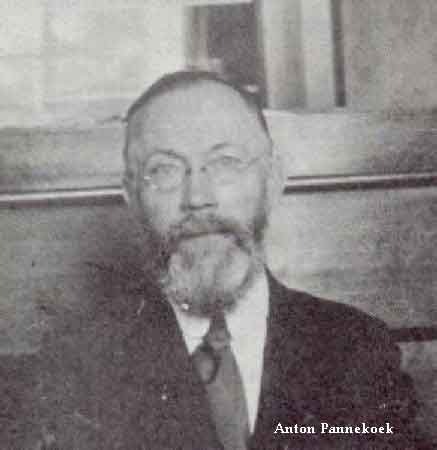

Translation and introduction by Rida Vaquas. The original text in German can be found here.

Anton Pannekoek is well-known as one of the principal theorists of council communism, a man who broke from both the traditions of Kautskyist social democracy as well as Bolshevism. By 1935, this break had crystallized into a clear attitude against the party as an instrument for working-class liberation: “a party is an organization that aims to lead and control the working class.”1 However, Pannekoek was very much a child of orthodox Second International Social Democracy, and a self-described pupil of Karl Kautsky, just as much as Lenin was. By presenting a translation of this short text, I hope to emphasize the Social Democratic inheritance of Pannekoek and the continuities of council communism with radical readings of Karl Kautsky.

The essay ‘The Propertied and the Propertyless’ was originally published in the SPD paper Leipziger Volkszeitung and eventually compiled as one of seven essays in a pamphlet Der Kampf der Arbeiter (The Struggle of Workers) in 1907. Much of Pannekoek’s early career in German Social Democracy resulted from his close friendship with Kautsky. After the German authorities prevented Pannekoek from taking up his position at the SPD Party School, it was Kautsky who found him alternative positions, including writing a weekly column for socialist newspapers. Kautsky’s aid hence embedded him into the German socialist movement and Pannekoek eventually moved to Bremen, where he was part of ordinary party life.

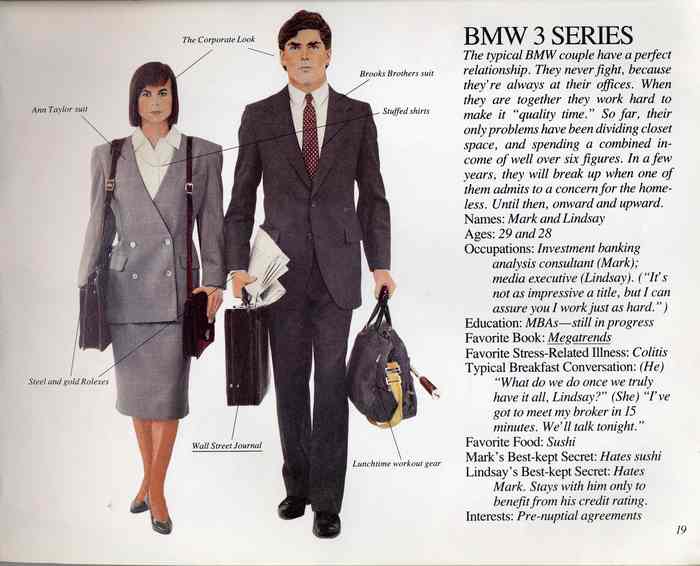

It would be wrong to construe this as simply a close personal friendship: Kautsky and Pannekoek shared a political outlook about the world. Both were representatives of the last great generation of scientific socialism. This was not ‘scientific’ in the sense of a vulgar determinism in which one keeps vigil for the final set of statistics that make revolution inevitable, but scientific in that it posited hypotheses and demanded proofs, one had to show their working when they claimed to solve the formula of social change. An amusing article in the SPD’s satirical magazine Der Wahre Jacob in 1912 aptly illustrated their affinity in approach, even when their conclusions differed. In an imaginary debate about fashion, Kautsky writes a beautiful chapter about the “genesis of trousers” in the emergence of humanity, ending with the proposition that had Adam had trousers, he may not have bitten into the fatal apple. Pannekoek, who had witnessed the conversations with Kautsky, reproaches Kautsky for having overestimated the role of trousers as a Marxist.2

This exchange mirrored the real split between Kautsky and Pannekoek that first became public in 1911-12 (one may note that Pannekoek split with Kautsky somewhat later than Rosa Luxemburg did) in a debate in Die Neue Zeit about mass action, in light of the 1911 strikes in England. Kautsky outlined a perspective in which the development of capitalism causes the emergence of mass actions by periodically creating conditions of extended unemployment, taxation pressure, inflation, and war.3 However, the development of the organized proletarian masses, through the institutions of Social-Democracy and the trade unions, changed the character of mass actions to ensure both that defeat is not a disaster and that victories are enjoyed by the proletariat, and not exploited by a faction of the enemy. Yet Kautsky’s case against embracing spontaneous mass actions as a tactical principle is simple: they are completely unpredictable and hence nothing can be said about what is to be done when they arise in advance, the party can only ensure that it is not caught off guard by them, by building up its own understanding of state and society and power.

What marks Pannekoek’s response to this analysis is his own disappointment with a great master of Marxism. In his view, although no one had proven the significance of Marxist theory as much as Kautsky did in his historical writing, in this instance Kautsky had “left the Marxist tools at home” and hence obtained no result.4 For Pannekoek, contemporary mass action differentiated itself from the mass actions of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries because the class who carried it out had changed: from bourgeois to proletarian. The distinction between the unorganized and organized is irrelevant, as many of the unorganized are capable of the same proletarian discipline and solidarity through the conditions of their work. In Pannekoek’s most cutting perspective, Kautsky “is not doing himself justice” in claiming he is unable to ascribe a particular political character to the masses when he has successfully done so for parliamentary politics.

It becomes clear that Pannekoek’s first critiques of Kautsky’s Marxism emerged from wanting to push it beyond its limits and seek to apply it to new scenarios. Pannekoek’s ultimate conclusion in 1912 was that the party must instigate revolutionary action at the right moment, not when the masses can simply no longer be held back, but when the conditions mean that large-scale actions by the masses have a chance of success. Only later disillusionments turned him away from the party form altogether. There is much merit in Pannekoek’s objection to Kautsky that one has not determined very much at all if the determination is that the masses are unpredictable. Yet it was clear that Pannekoek’s own formulas didn’t hold up in the light: the masses by no means tend towards radicalism in all cases, and there has been no guarantee that they would rise against war. In their final parting of ways, both Kautsky and Pannekoek sought a more rigorous application of a Marxist framework they shared from each other.

This translation demonstrates the analytical clarity that this Marxist framework had to offer at its strongest.

The political struggle that the socialist working class leads and of which every election campaign is an episode is not in the first instance a struggle about particular political institutions and legal demands, but instead a universal struggle between the propertied and propertyless class. To understand it correctly, it is necessary to take a close look at the combatants, the causes, and the aims of this struggle.

According to this classification of both of the parties in conflict, it may appear that the ownership of money or income is the basis for class division. This is how it’s often understood by our bourgeois opponents. They take income or assets statistics in their hands, draw a few lines that separate the low from the middle incomes and the middle from the high incomes, and believe that they’ve obtained an insight into the class relations of the present-day. Even more comically, they do this when they present a statistic from the Middle Ages or the eighteenth century and from this prove that there were proportionately just as many low, middle and high incomes at the time as there are now and with this they believe they have refuted the concentration of capital, the demise of the middle class and the escalation of class contradictions.

These poor jokers, who want to demonstrate away the obvious facts of the great social upheaval in this way, clearly don’t have the faintest idea of what a social class actually is. A class is not a group of people that have the same size of income, it is instead a group of people who fulfill a particular function economically in social production. We say ‘economically’ so that you don’t fall for the idea that the technical side of work is understood as the social function. A weaver and a typographer professionally have a different function, technically their work is varied, but economically they are both waged workers and belong to the same class.

In the manifold diversity of the social production process it is no wonder that a colorful picture of the most diverse social classes appeals to the eye. In industry, capitalist employers stand against waged workers; from this universal fundamental relationship, different class relationships are built up, according to the scale of the industry. The independent craftsman concurs with the capitalists that he is an independent businessman, but he employs no waged workers. And the small masters of artisanal small enterprises, just like shopkeepers, are even described in colloquial language as separate from the large-scale capitalists, as the middle class. Their difference consists in the smaller number of workers and the smaller amount of capital, without it being possible to identify firm boundaries between the two groups. In large industry, a group of overseers and technical work managers slide in between the capitalists and the workers. The high technical and scientific demands placed on today’s large and giant conglomerates have called into being a class of private technical and scientific officials that form the ‘intelligentsia’ alongside similar and equally-placed public officials. Economically they belong to wage workers as even they sell their labor power—a special intellectual labor power trained by long studies and better paid—for wages. The higher level of wages, i.e. their very different living standards, again separates them from workers. At the same time, the development of large industry has effected a separation between the industrial entrepreneur, who lives off profits, and the owners of money, who live off interests, through the vast amounts of capital that it demands. In the stock company, a paid official even steps into the role of the employer, the director. The double function of the capitalist, to direct production and to pocket the surplus-value, has been divided between two types of people. However, all finance capitalists cannot be lumped together, just like all industrial capitalists. According to their size, a differentiation persists like in the world of fish in the sea: the big devour the little. A little rentier is as much a finance capitalist as a member of high finance, but to these stock market wolves he is a stock market lamb as it were and hence his social role is another one.

If we now take a look at agriculture, we find the same gradations, even if not in exactly the same way, as in industry. Only a class is added here, because the landowners, through their monopoly, can extract a ground rent from the yield of agriculture without playing any active role.You have dwarf peasants, small farmers, medium and large farmers and farmworkers. Here the hybrid and transitional forms are emerging that confuse the picture of social classes to an untrained eye. The agricultural workers often have a small plot of land, while owners of smaller plots of land, too small to live off, seek additional income as agricultural or even industrial workers. They are hence simultaneously independent landlords and wage workers. In the home industry we find supposedly independent craftsmen that are totally dependent, body and soul, upon capitalist businessmen. That the legal form of waged service doesn’t suffice to ascertain class is shown by the numerous transitions from the paid director to the worker, via subdirector, head of department, chief engineer, technician, draughtsman, supervisor. Here one will often be at a loss to define precisely, in the gradual transitions, which class distinctions one must accept and where their boundaries lie.

So social life offers a colorful picture of the most diverse classes whose functions, and hence interests, directly show sharp contradictions and enormous differences and even gradual transitions. Isn’t this picture a resounding refutation of our assertion that only two classes stand against each other in the social struggle? And doesn’t a look at the varied functions of classes immediately show that the definition of two groups, only according to their assets is unscientific and unsustainable— a fictitious assertion only for the purpose of demagogic sedition?

No. This definition is substantiated in the social order in its deepest essence. It emerges from the specific role that money plays since the advent of capitalism. All money has the characteristic of being able to work as capital, i.e. when the owner buys the means of production with it, rents workers, and sells the commodities they produced, it comes back in their hands as more money, as larger, as capital blessed by surplus-value. They do not even have to do it themselves, with the greatest pleasure others will take away the stress and worries of running a business and pay them part of the profit as interest for the use of their capital. Money has acquired the characteristic of bringing its owner interest through capitalism. Whoever has access to money can hence secure an income without any work.

This income comes from surplus-value which formed in the process of production. The working class brings into being vast quantities of value through their work; they only receive a part of it back as wages. The remainder is surplus-value which falls to the capitalists. This surplus value must be distributed amongst the different capitalists and groups of capitalists because they all live from it. The landowners demand their share, the businessmen and middlemen ask for their share, the directors and highly paid industrial managers take their piece, the finance capitalists obtain their interest or dividends. They fight amongst themselves about the distribution of surplus-value. The distribution is partly decided by economic laws and partly by political power balances. What matters to us here is the fact that all those who have money are thereby entitled to a certain extent to some of the surplus-value, provided of course that they do not hide it in an old stocking like the former misers. The surplus-value is created by the exploitation of the lower classes whose work produces that surplus; all those classes who share the surplus value among themselves together form a great society of exploitation, and everyone who has money is thereby, by the grace of Mammon, a shareholder in this excellent corporation.

This is the reason we can speak about a great class contradiction between the propertied and the propertyless. It is because these words are synonymous with the exploiting and the exploited classes. Whoever doesn’t own anything is forced to sell their labour-power to the owners of the means of production, i.e. indirectly to the owners of capital, in order to live. These capital owners give them a wage for long and hard work, which only suffices for a poor living standard, and the remainder of the worker’s produced value goes into their pockets. Whoever does not own anything must allow themselves to be exploited, the private ownership of the means of production cuts them off from any other way out. The situation remains mainly the same even when the worker owns a little bit of money, the interest of which forms a small subsidy to their wages. Even if they have money at the bank, they are still not exploiters. In this interest, they only gain a tiny little piece of the great mass of surplus-value which is squeezed out of the entire working class, and this little bit doesn’t even come into view next to the surplus-value they contribute to the total mass by their own wage labor. They increase surplus value and are exploited, they find themselves in the same situation as their comrades. And as a rule, they regard this money not as capital but as a saving fund by which they will meet their needs in the case of unemployment or accidents.

But as soon as the wealth exceeds a certain level, it enables the owner to live from exploitation instead of his own work, modestly if he is a small rentier or entrepreneur, lavishly if he is one of the rich. As much as there are class differences among these people, as much as they perform different active or passive functions in the exploitation process, as much as they still struggle with each other for their share of the spoils – the reason why their property is not always secure – they do have a common interest because they are all participants in the exploitation. In the great social opposition between exploiters and exploited, the size of the fortunes within the community of exploiters is not important. Equally, it follows from this discussion that we do not claim that society consists only of these two large groups. There is a layer between them, of which it is impossible to say whether it is closer to one or the other group, such as a peasant who exploits workers and are themselves exploited by the landlord, or a civil servant who receives a mediocre salary. How they will stand in the great political struggle can only be determined from a particular examination of their class situation. But for the greater masses of people and classes, in the vast political struggle their various specific social functions will stand behind the basic question of whether they belong to the propertied or the propertyless, that is, to the exploited or the exploited.