This essay, written by anti-fascist militant Antonin Bernanos while in a French prison, provides an important perspective on the relation between the state and organized fascism in France. Bernanos was arrested in April 2019 and released mid-November. Translation and introduction by Joe Hayns.

In the last weeks of April, protests against police violence again erupted across France’s quartiers populaires, compounding with crises of health, work, even food.

Following the police’s ‘severely injuring’ a motorcycle rider in the Parisian suburb of Villeneuve-la-Garenne, rapper Dosseh said: ‘Don’t be surprised if it starts again like 2005’.

But if features of the recent riots are indeed similar to those of 2005 – a month of unrest across poorer working-class neighborhoods after a police chase resulted in the death of two teenagers – we might ask, how has the state itself changed? Are they more or less restrained, more or less empowered? How have successive waves of opposition – student protests, rail workers’ strikes, the Gilets Jaunes movement, et cetera, and only since Macron’s 2017 presidential win – fortified its repressive apparatus?

Below is an analysis of state revanchism in France, with a focus on the collaborations between the police and far-right forces against those progressive movements. It was written last summer by the anti-fascist activist Antonin Bernanos whilst held in the notorious La Santé prison – as he explains, less a legitimate sentence than evidence itself of such collaboration.

We thank the editors of Contretemps, and congratulate Bernanos on his freedom.

I am writing to you from la Santé, where I have been incarcerated following a legal process begun on 18 April against several people, after a confrontation between anti-fascists and far-right militants.

That makes it nearly six months that I’ve been imprisoned; six months through which I’ve suffered numerous pressures from both the judiciary and the prison administration. I was initially jailed in Fresnes prison, in Paris, where the management kept me solitary confinement for being a member of “radical and violent circles of the far-left”. Then, while in overnight transit to a secure establishment outside the Île-de-France region – according to the prison authorities I might have benefited from “outside support that could harm the security of establishments of greater Paris” – I was transferred here, to La Santé.

Two months ago the judge in charge of my case ordered the end of my provisional detention and for me to be freed – a decision that was annulled in an appeal court by order of the Paris prosecutor, who used his judicial powers to block my liberation. Such determination – fairly typical of the courts and penitential administration – is exercised against me when all others incriminated in the case have been freed and placed under license, and when there’s nothing in the case linking me in any way with the confrontation.

Nothing, except the word of an identitarian militant, Antoine Oziol de Pignol: a Kop de Boulogne hooligan with the Paris Militia, active with Génération Identitaire (GI), and close to the small nationalist group Zouaves Paris, who he was with at the time of the confrontation [Kop de Boulogne, the Paris Saint-Germain ultra’s terrace]. Pignol has lodged a complaint, and as plaintiff has claimed to recognize anti-fascist militants amongst the perpetrators of the violence he was victim to. He has declared that I was part of the group that routed him and his comrades on the evening in question.

At first glance, the fact that far-right militants, as members of these violent groups and themselves perpetrators of numerous attacks over the last months – from GI, against veiled women, migrants, and the youth of the Lycée autogéré (Self-Run High-School); from the Zouaves Paris again the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste rally during the Gilets Jaunes’ Act 11 – could collaborate so straightforwardly with the police and repressive agencies may seem surprising. It helps though to place this phenomenon in a wider frame, in the context of the social revolt and the generalized repression that we have seen since the struggle against the 2016 Labour Law and throughout the Gilets Jaunes’ movement.

Indeed, even if the links between the far-right and the police need little further demonstration – see the case of Claude Hermant (customs inspector, arms dealer, GI member), or the strange lack of interest in far-right leader Serge Ayoubm’s role in the 2013 murder of leftist Clément Méric – we should look closer into the specific melding of such groups and the police.

Génération identitaire has always positioned itself as the state’s helpmate – its occupying of mosques, as Islamophobic policies proliferate; the ‘Defend Europe’ campaign to stop migrants at the Alps and the Mediterranean, as European migration policies radicalize, and thousands of men, women, and children lose their lives crossing; and most recently, their occupation of the Caisse d’allocations familiales (family welfare) office in Bobigny, northeast of Paris, at a time of unrestrained repression against the largest movement in decades against precarity.

On the Zouaves Paris, we should recall their multiple attacks against students and militants during the 2018 university shut-downs and occupations against the Student Orientation and Achievement (OAS) Law.

It is also the Zouaves who on 1 May 2018 attempted to ratonner (‘rat-hunt’) demonstrators at the Place de la Contrescarpe (a central Paris square), at the very moment when Alexander Benalla and his heavies were beating those people refusing to leave – and this following a day of furious police violence against an international demonstration of workers.

If this event was emblematic of the articulation between the violence of the police, the violence of armed state groups such as Benalla’s, and the violence of far-right groups, it is amongst the movement of the Gilets Jaunes that we can see this shared strategy deployed and consolidated.

Though far-right groups have finally been chased from the movement at the national level, recall that during the first weeks their presence was very real – and remember especially the repeated discourse in the mass media, according to which the violence against the forces of order was committed by nationalist groups who had ‘infiltrated’ the movement.

If it is true that certain far-right groups such as the Zouaves and their Bastion Social clique participated in confrontations with the forces of order from the beginning, we should understand this fact and its media representation in the context of a larger strategy, one beneficial to the state. It was necessary to develop a moral repression, stigmatizing the Gilets Jaunes as of the violent far-right, which made possible the ferocious police repression that we would come to see.

The presence of far-right groups was thus established, maintained, and instrumentalized in order to legitimize, in the eyes of the public, the huge number of arrests, the expedited courts and sentencing, the imprisonments, the violence, and the mutilations. Maintaining the presence of the far-right – and its publicity – was the means for the state to render a movement, followed by a large majority of the population, illegitimate.

Yet another attempt at manipulation of public opinion, which was deployed to its maximal extent during the polemics surrounding the ‘assault’ of right-wing media personality Alain Finkielkraut, and the ‘antisemitism of the Gilets Jaunes’. To be clear: This is not to deny the antisemitism and conspiratorial thinking that was able to spread throughout the movement but to reveal the state’s tools of moral repression – and to understand that fascism and its ideas are amongst the most important.

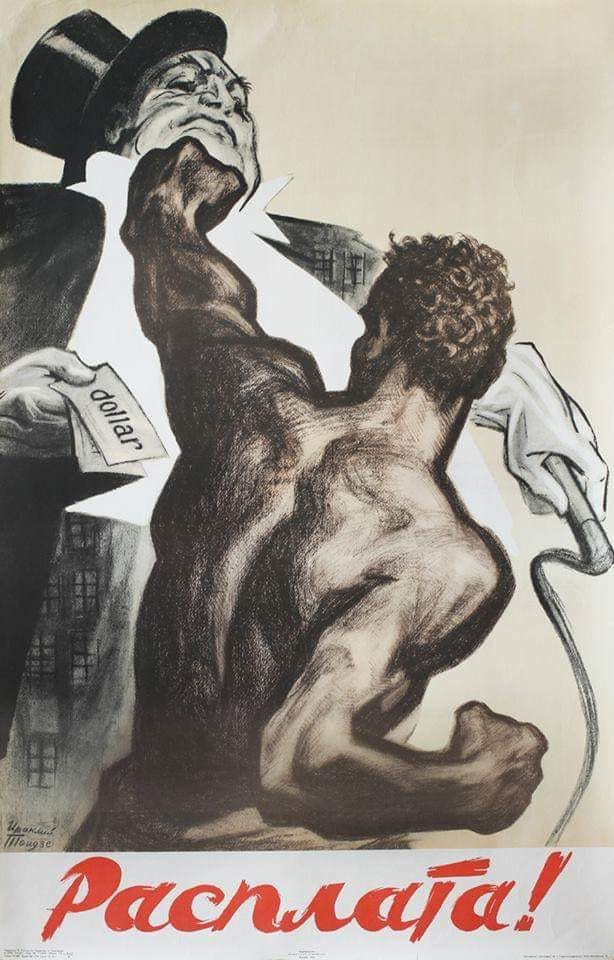

Antisemitism, of which the state boasts itself the staunchest opponent, must be understood as a tool: as a reality deliberately maintained. If the notoriously antisemitic theses of (far-right author) Alain Soral have been able to spread through the movement via the militants and auxiliaries of the far-right, it is because they have been hugely exacerbated and relayed by the mass media and the government. And if this is the case, it is because these supposedly “anti-systemic” theses are, in reality, at that system’s service, and are mobilized according to its methods.

From the outside, the state uses it to delegitimize the movement in the eyes of the public. From the inside, the theses on ‘Jewish finance’, or the Rothschilds, allows real enemies – such as finance in a broader sense, and capitalism as a system of domination and exploitation – to be isolated off, to be brushed aside. The target becomes an alleged part of the problem, not the problem itself: and, yet again, the state’s repressive aim and the fascist strategy are as one against the social movement.

To return to the movement. The presence of far-right groups such as Zouaves Paris amongst the Gilets Jaunes was not merely a regime scarecrow. The group was there to hunt antifascists, and autonomist and revolutionary militants; to attack those people already targeted by police forces, due to their giving logistical and strategic support to the movement both during demonstrations and economic blockades and as an active self-defense force against the police.

Part of the far-right’s military strategy was the attempt at infiltration of the services d’ordre (stewards), as revealed by the presence of infamous identitarian militant Victor Lenta as self-proclaimed member of the ‘Zouaves de service’. Once again, the fascist strategy plainly echoed a strategy for maintaining order. The far-right had to cohere the leading parts of the movement in order to attack antifascist groups, and impose an authoritarian framework onto demonstrations – in order to repress any and all outbursts, and muzzle those new forms of offensive struggle specific to the Gilets Jaunes, as they surged across the political field.

This was the last real organizational effort of the fascist forces. By staking out an antifascist terrain, militants and anti-racist Gilets Jaunes chased out the far-right in Paris, Lyon, and elsewhere: their presence was unacceptable and non-negotiable. Through becoming an actor within the movement, ignoring injunctions to boycott it – often coming from ‘militants’ in our own camp, fooled by the state’s formula: ‘Gilets Jaunes equals Far-Right’ – our everyday efforts paid off.

The struggle every Saturday over numerous weeks would not have happened without our close collaboration with groups of Gilets Jaunes at the local and national level – it did not only involve street clashes with fascist militants. Autonomous activists and antifascists placed themselves at the service of the movement, both strategically and logistically, accepting the numerous contradictions it involved, transforming and accepting being transformed, thereby breaking away from sclerotic forms of political contestation.

For this mobilization, it was necessary to use new strategies and new forms of struggle: Physically confronting far-right groups, organizing the protection of their targets, and starting party and anti-racist rallies, and also participating in local general assemblies, being present on roundabouts and the blockades, mobilizing our skills and knowledge to organize anti-arrest groups, and protecting the rallies against the violence of forces of order.

All of this was made possible thanks to the collaboration between comrades with often very different political horizons and, most importantly, thanks to our alliances with Gilets Jaunes at the local level, particularly the young gilets of Rungi in the south Paris region, without whom the successes of Paris would not have been possible. And it is precisely these alliances, these encounters, this political work that is targeted by the judicial process that has led to me being incarcerated today, and which places autonomous antifascism itself in the dock: a shared strategy of the far-right and the repressive institutions which via the law aims to attack the movement and its different protagonists.

What I have written above is nothing new. For decades the French state and the far-right have been intimately linked in the defense of neo-colonial capitalism – since the Algerian war and the inauguration of the first state of emergency, which was again utilized to quell the revolts of the popular neighborhoods in 2005, and again against Muslims under the pretext of anti-terrorism. Now it is wielded against a social movement and society as a whole, following the constitutionalization of the emergency prerogatives used following the November 2015 attacks.

If the convergence between working-class neighborhoods and the Gilets Jaunes remains, for the moment, in an embryonic state, we must remember that the state’s violence has for a long time linked the inhabitants of the banlieues with the fringes of the popular classes, as currently organized through the Gilets Jaunes, making them now prime targets.

The violence falling on the Gilets Jaunes movement has been developed over many decades. The doctrine of ‘maintaining order’ was elaborated first during the repression of people struggling for freedom in the former French colonies – the BRAVs (mobile police units) are simply the successors of the BAC, as created to punish the internally-colonized people after the war for Algeria. The flash-balls and stun grenades that have so mutilated the Gilet Jaunes are instruments perfected over the years in the great cities’ banlieues.

And behind all this violence, fascism watches, always ready to mobilize as an instrument of the same violence. Since the Organisation armée secrète1 the far-right has recruited amongst the police and military to commit attacks against Algerians. Since the 1980s – when fascist groups ‘rat-hunted’ foreigners – the baton has been handed to the forces of order, who simply retook the monopoly of racist violence – and now we see everyday police aggressions, which continue to humiliate, mutilate and kill the residents of working-class neighborhoods, because they are poor, black, Arabs, or Muslims.

For a long time then, the police and fascist groups have shared this racist violence, and today it is this same violence, co-built by the far-right and the forces of order, which is mobilized against the Gilets Jaunes movement and its different actors. The police and the far-right collaborate on a shared project: to quash the popular revolts and defend the capitalist system.

The last weeks have offered a concentrated spectacle of this process, one that never ceases to amaze. The police, radicalizing without restraint, increasingly act as an autonomous force: We think of Steve Canico of Nantes, killed during a music festival; of the illegal demonstration outside the HQ of La France Insoumise, as called by the far-right group Alliance; and, most recently, of the police’s questioning of Assa Traoré2 for holding a children’s self-defense event – yet another insult, in a trial without apparent end. At each step, the police get the unqualified support of the government; with each new crime, they can count on its systematic protection.

Over the same period, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen3 and far-right commentator Éric Zemmour have competed over the viciousness of their rhetoric, and call without embarrassment – on television, watched by millions of French people – for pogroms against Muslims.

And Macron, who did well presenting himself as a bulwark against the far-right, hasn’t only been content to blindly follow an unleashed police force, but has also decided to launch an anti-migrant campaign, using the literal words of the far-right.

The proper position is not, as passive, scared social-democrats think, to see the symptoms of some shadowy future, the stirrings of some coming fascism, against which the only defense is trust in self-described “progressives” and other defenders of a “republican front”. The situation before us is quite the contrary: fascism is not on the horizon, but a material tendency developing in the present, amongst even official institutions – and one that Macronism, far from serving as a bulwark against, is itself accelerating.

It is with this authoritarian mutation of the state that the nascent social movements – in their tentative alliances and reciprocal reinforcement – will be confronted.

I am not therefore only claiming my own freedom and the dropping of charges against the accused antifascists. Even if it is one of the fronts of struggle before us, it would be sterile and sectarian to remain centered only on ourselves – to ensure only the defense of our own forces – when the repression is crashing against the fringes, larger and larger, of the popular classes. If one of the great strengths of the state is the art of deception, of the deconstruction of truth, of the manipulation of facts and their mediatized rewriting, own our role as antifascists is to reaffirm the real, fundamental link which unites these current struggles, from antiracism to the struggles against precarity.

We must not forget the Gilets Jaunes wounded and imprisoned in the jails of the state. I have come across many of them behind the bars, so often isolated, forgotten, destitute of any political support; and we must not forget all those who dwell in French prisons, locked up for what they are, for what they represent. If it is to be, all revolutionary struggle will be anti-carceral.

We must not forget that all these things are linked in a project that we must fight, but also, and above all, we must not forget that all the words, all the texts, all the principled postures mean nothing if they are not concluded with acts. The sequence of emerging struggles must come from the alliances wove, from common fronts built over the years – for a popular self-defense of all revolts.