Social Conservative defenses of the nuclear family pose it as the default natural form of kinship and blame working-class immiseration on its decline. Cam Scott takes aim at such arguments, including those made by leftists.

As the deepening crises of capitalism impel greater numbers of people to the left, the communist movement gains in strength. These numerical gains, however, bring about another slew of contradictions, as false friends and ideological seductions appear in a myriad of intimate guises. In imperial core countries such as the United States, a new brand of majoritarian socialism, backed by common sense, gathers around a program of drastic, but ultimately serviceable, reforms to the capitalist system. Within this recent ferment, opportunism flourishes, and right-wing talking points proliferate with the advantage of simplicity.

A persistent example of rightism within a widening socialist spectrum would be Angela Nagle, who made her debut as a cultural critic with the 2017 publication of Kill All Normies, a remedial ethnography of the online right and its misogynist ressentiment. Perhaps the author’s sympathies were already clear from this early screed against “Tumblr-liberalism,” in which Nagle more or less describes a penchant for denunciation from a “campus left” as a self-fulfilling prophecy, goading its nemesis into existence by sheer wishful hyperbole. But it was only after Nagle published a piece in the conservative journal American Affairs entitled “The Left Case against Open Borders,” calling internationalists “the useful idiots of big business,” that she attracted the interest and agreement of pundits like Tucker Carlson, and a reputation as an “anti-woke” culture warrior. Most recently, Nagle has turned her attention to the family—more specifically, to its defense against a deviant left—for The Lamp, a journal of “consistent, undiluted Catholic orthodoxy.”

As a moral institution, the bourgeois family proves a remarkably effective figure with which to condense Nagle’s racial and sexual politics. Her polemic opens defensively, like so many conservative rallying cries, positioning the family as an institution under attack: “The call to abolish the family has recently been revived by cultural revolutionaries who are getting their way on a number of issues to which most people had never given any consideration.” Beyond the lurching grammar of this curious assertion and its uncertain timeline lurks a fantasy of persecution. Nagle warns her reader of a return; but from whence does this renewed demand originate? Without addressing the pre-history of this apparently perverse fad, Nagle proceeds to ask a follow-up question: “Why is it being revived now, when the family has already been in decline for decades?”

Here one perceives a sudden and deceptive shift, for there’s a wide difference between ‘abolition’ and ‘decline.’ Any revolutionary will profess a desire for the abolition of capitalism, at the same time as they will almost certainly understand that any interval in which capitalism finds itself in decline is sure to be a time of intense cruelty, when its most oppressive institutions reassert themselves. Historical structures, particularly those that ought to be transformed altogether, often enter into periods of decline because of their own contradictions. Decline has never sufficed for revolution in itself; more often, it names the intolerable stage of an untenable state.

Leaving aside this sleight, the question remains: who are the cultural revolutionaries behind this revival? In a scaremongering rollcall of family abolitionists, Nagle includes “anarchists,” Black Lives Matter, one defunct magazine, and apparently, by implication, the Ford Foundation. With this roster of variously wretched and connected nemeses, Nagle panders to a moral majority, for whom—to the extent that she still claims any left politics whatsoever—she is determined to play the useful idiot. Nonetheless, only an extremely online reader could follow Nagle’s paranoid synopsis, in which she digresses upon the short-lived Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle, characterizing organizer Raz Simone as a “warlord” with the racist panache of a Fox News telecaster, and seethingly obsesses over the work of theorist Sophie Lewis on surrogacy.1

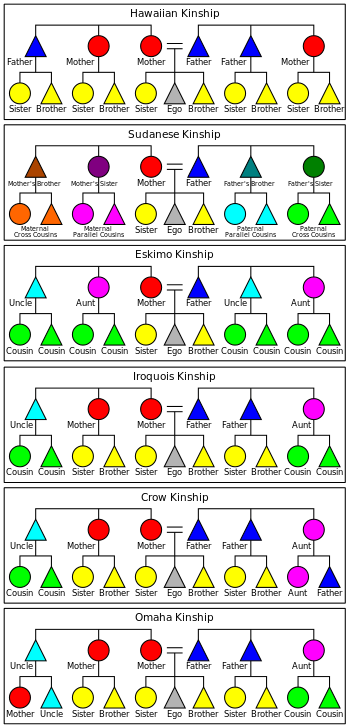

Nagle appears certain that the family, as a unit of social production and necessary (however often obliged, coercive) care, follows natural law, and can be extrapolated from biological descendence. The nuclear family, she asserts, is a cornerstone of “virtually every society hitherto observed in human history.” This is demonstrably false, as well-observed by many decidedly non-radical sociologists and anthropologists. But one needn’t heed any academic in particular, where innumerable cultures world-over call attention to the socially corrosive imposition of the nuclear family form on their own kinship practices and ways of belonging. Nagle is something far worse than incurious, however—she is a reactionary, and the willingness of some on the left to take her seriously warrants a materialist summary of the ground on which she intervenes.

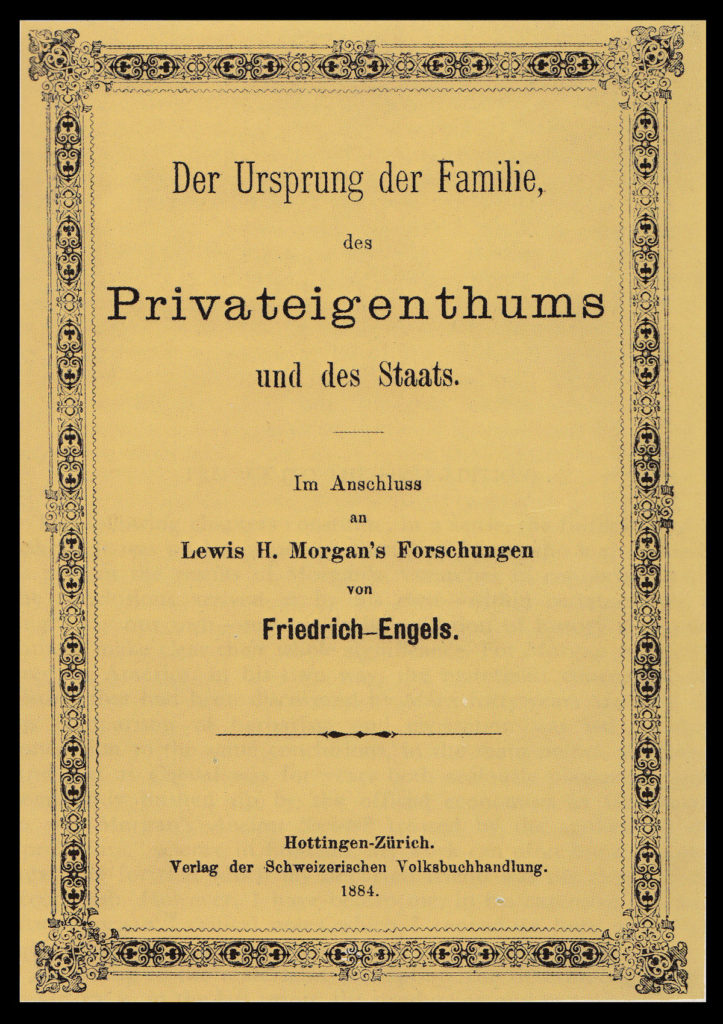

The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State

In 1884, Friedrich Engels published The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, a historical excavation of the development of the family in consequence of changing relations of production. While clearly dated, the work is a cornerstone of Marxist and feminist theory, in which Engels argues that the patrilinear organization of the modern family develops with the advent of private property, in order that “children of undisputed paternity (might) come into their father’s property as his natural heirs.” It is worth quoting at greater length from the text:

Monogamous marriage comes on the scene as the subjugation of the one sex by the other; it announces a struggle between the sexes unknown throughout the whole previous prehistoric period. In an old unpublished manuscript, written by Marx and myself in 1846, I find the words: “The first division of labor is that between man and woman for the propagation of children.” And today I can add: The first class opposition that appears in history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamous marriage, and the first class oppression coincides with that of the female sex by the male. Monogamous marriage was a great historical step forward; nevertheless, together with slavery and private wealth, it opens the period that has lasted until today in which every step forward is also relatively a step backward, in which prosperity and development for some are won through the misery and frustration of others. It is the cellular form of civilized society, in which the nature of the oppositions and contradictions fully active in that society can be already studied.

In Engels’ account, it isn’t only that the nuclear family appears at a particular moment in history as a requirement of capitalist accumulation. Rather, the patriarchal distribution of property in relation to a gendered division of labor preconfigures class society. Theorist Shulamith Firestone believes that “Engels has been given too much credit for these scattered recognitions,” and that his work perceives the “sexual substratum of the historical dialectic” only insofar as it aligns with his own principally economic concerns.2 But it is precisely this alignment to which Nagle and conservative socialists must be accountable. Any serious examination of the emergence and maintenance of capitalism has to account for the development of the nuclear family, and any thought that attempts to circumvent the historicity of this development by reference to natural advantage is unsuitable to the critique of capitalism.

Over the course of his influential work, Engels narrates the rise of institutionalized patrilineality as a means of transmitting private wealth from generation to generation; and the Marxist demand for the abolition of all rights of inheritance makes little sense without a firm historical grasp of the institutions by which unyielding, multi-generational ownership of the means of production is naturalized along patrilineal, and racial, lines. At the same time, socialist feminists such as Selma James and Silvia Federici have demonstrated the extent to which the family as a minimal unity was essential to the success of free labor, where women and children necessarily tend to a household owned by a man. This is not only a holdover from a feudal arrangement; rather, as John D’Emilio explains in his influential essay on gay identity formation, family members remain mutually dependent under the capitalist mode of production, even as the family ceases to function as a self-sufficient unit of production. As individuals struck out into the market, selling their labor power, new principles of social affiliation emerged. It is the decline of this mutual dependency that Nagle and other defenders of family values bemoan:

Robert Putnam’s famous work, for example, documents the steady decline of social trust, community, and cooperation in the same time period during which the family has declined, with loneliness and isolation increasing by every statistical measure to a greater extent now than at any point in American history.

One should ask, however, what else has taken place over the decades in question. Correlation does not imply causation, and as Nagle herself claims to have noticed, almost every collectivity has been threatened by massive deregulation over the last half-century, from organized labor to team bowling. This citation on its own is specious; if proletarianization erodes family values, it in no way follows that this erosion is the cause of other, related symptoms; nor does it follow that the nuclear family as a feudal vestige must be defended. Nagle disagrees:

In the Eighties, the wealth gap that opened up between the educated and less educated due to offshoring and the decline in opportunities for the working class is considered one of the primary causes of family break-ups by sociologists such as Andrew Cherlin, the author of Love’s Labour Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class Family in America. While the working-class family suffered under these economic conditions, family stability increased among the educated. This disparity has in turn exacerbated the wealth gap further. The many demonstrable positive benefits of growing up with two parents are among the many evils of the past from which the working class and the less educated appear to have been liberated.

Moving swiftly past the sleight of hand by which Nagle smuggles her economic nationalism into her defense of the family, she again confuses the disaggregation of the family by economic pressure, and the pains of further isolation from this minimal unity, with an abolitionist program of affirmative affiliation. Cherlin uses an apparent “marriage gap” to index the economic gulf between classes, and before any normative interpretation, this observation—that a stable family structure strongly correlates with economic security—is easily reconcilable with much Marxist and abolitionist thinking on the family. As noted, the family is a miniature unit of production and wealth-sharing in an otherwise atomized market society. As a legal institution, the family functions as a firm, by which wealth is inherited and inequality is reproduced. Otherwise, the security afforded to working people by the family is carefully annotated within Marxist sociology and feminist thought, which describes the family as a site of occluded labor, where unpaid domestic service is expected: the waged worker doesn’t reproduce themself alone.

Making and Breaking Kin

This reply is far too abstract, however, where Nagle’s racist innuendo is so brazen. Nagle’s assertions about the benefits of growing up in a two-parent household are either banally true, concerning the material advantages of pooling multiple incomes or having the full-time attention of an unwaged, stay-at-home caregiver—or they partake of the deep stereotypes used to ideologize American economic policy. Bluntly, Nagle’s determinism has less to do with Karl Marx than with Daniel Moynihan, whose 1965 report on Black poverty in the United States famously pathologized its subjects, venturing a dismal verdict on Black men and single mothers. As Angela Davis writes:

According to the report’s thesis, the source of oppression was deeper than the racial discrimination that produced unemployment, shoddy housing, inadequate education and substandard medical care. The root of oppression was described as a ‘tangle of pathology’ created by the absence of male authority among Black people!3

In this document, Moynihan framed the adverse effects of poverty and discrimination as evidence of the incompatibility of Black “matriarchal” custom with European American social mores and progress. Moynihan’s description of this alternative family arrangement was in no way ennobling—rather, this comparative term functioned to naturalize the bourgeois nuclear family and its constitutive divisions of labor and to prioritize this organization as a requirement of economic advancement.

In a historically sweeping, meta-psychoanalytic reading of the Moynihan Report, theorist Hortense J. Spillers explains its fatal logic and flawed terminology. The report, she says, purports to compare the “’white’ family, by implication, and the ‘Negro Family,’ by outright assertion, in a constant opposition of binary meanings … with neither past nor future, as tribal currents moving out of time.”4 These two family forms, insofar as they are binarized and reference only each other, lack historical substantiality themselves while operating within a racist imaginary that is itself a historical product. The synchronic Oedipality of Moynihan’s account evades the history of which it is a product. This supposed cultural difference only stands for failure and exclusion where the family is both an amenity and an institution of whiteness:

It seems clear, however, that ‘Family,’ as we practice and understand it ‘in the West’—the vertical transfer of a bloodline, of a patronymic, of titles and entitlements, of real estate and the prerogatives of ‘cold cash,’ from fathers to sons and in the supposedly free exchange of affectional ties between a male and a female of his choice—becomes the mythically revered privilege of a free and freed community.5

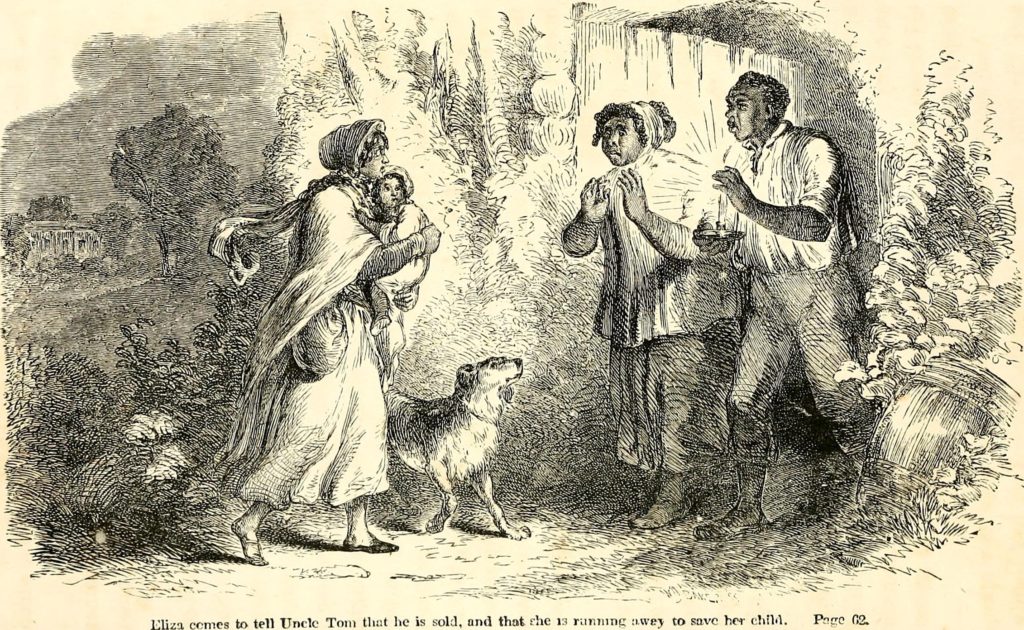

Any verdict as regards Black family life, Spillers suggests, is “impertinent” where enslaved people were forcibly dispersed from their own familial and social arrangements. Slavery is a system that makes kinship impossible, for if it remained so, Spillers explains, “property relations would be undermined, since the offspring would then ‘belong’ to a mother and a father.”6 Thus the Moynihan report’s improper speculation as to the obstinacy of a Black “matriarchal” culture suggests that Black women have been empowered to claim their children throughout history, on a model of inheritance that was systematically denied them.

As one can see, it isn’t simply that the nuclear family has outlived a once-upon-a-time utility, but that it has served continuously as an instrument of subjugation. Where many cultures were suppressed by European colonizers and prohibited access to the conceptual and material resources afforded by the family, others were disciplined into accepting its strictures over the course of forced assimilation. As Europe colonized North America, a patriarchal family unit proved particularly beneficial to the new economy, which in turn transformed vast territories shared by First Nations into private property. The family, as the maximum society permitted by this dispersal, doubled as a workforce; and the drive by individual households to maximize productive capacity changed the demography of North America. As Dakota scholar Kim TallBear explains:

Growing the white population through biologically reproductive heterosexual marriage—in addition to encouraging immigration from some places and not others—was crucial to settler-colonial nation-building … At the same time that the biologically reproductive monogamous white marriage and family were solidified as ideal and central to both US and Canadian nation building, Indigenous peoples who found themselves inside these two countries were being viciously restrained both conceptually and physically inside colonial borders and institutions that included residential schools, churches and missions all designed to “save the man and kill the Indian.”7

For all of her concern about child welfare and the breaking up of homes, Nagle remains ignorant of how the mandate of the nuclear family has been used to destroy other systems of multi-generational care. The seizure of Indigenous children by the state has been a permanent feature of colonization, from residential schooling to Sixties Scoop— the massive abduction of Indigenous children from their communities throughout the 1960s, and their adoption into middle-class settler families across North America. In Canada today, there are more Indigenous children in the custody of Child and Family Services than were placed in residential schools; which have been named an officially genocidal institution. These apprehensions have been similarly denounced by human rights advocates, and often proceed on the basis of discrimination against young, “single” parents or the greater role of older community members in care. On this point, TallBear quotes Cree-Métis feminist Kim Anderson: “Our traditional societies had been sustained by strong kin relations in which women had significant authority. There was no such thing as a single mother because Native women and their children lived and worked in extended kin networks.”8

Throughout her work, Marxist anthropologist Eleanor Leacock makes a forceful case for the historical subversion of the labor of women, and the consequent transformation of social relations, in the development of capitalism. Based on her time with the Innu people, and less fanciful accounts of Indigenous North American life and customs than Engels’ third-hand characterization of the Haudenosaunee, Leacock observes the even dispersal of rights and responsibilities among men and women, in a collective arrangement that considerably surpasses the narrowness of the nuclear family. In these societies, Leacock explains, “women retained control over the products of their labor. These were not alienated, and women’s production of clothing, shelter, and canoe covering gave them concomitant practical power and influence.”9

Having observed the economic equality of genders as independent parties to exchange in non-European societies, Leacock argues adamantly for a Marxist theory to account for the subordination of women in the emergence of the family, as a crucial prerequisite to the capitalist transformation of work into abstract labour and cooperative production into private property relations. For want of such an account, anthropologists and laypersons alike will repeat “the widespread normative ideal of men as household heads who provision dependent women and children reflects some human need or drive … (and) the unique and valued culture history and tradition of each Third World people will continue to be distorted, twisted to fit the interests of capitalist exploitation.”10

In arguing for a trans-historical family integrity, Nagle and her fellow moral crusaders implicitly condone a trans-historical—that is to say, natural—dependency of women upon men. This imputed dependency serves in turn as a firm foundation for a rigid conception of sex and gender, extrapolated from a division of labour and its concomitant system of property. Little wonder, then, that Nagle’s declensionist account of the American family fixates upon the project of queer liberation as a scene of turpitude. But even she may be surprised at certain reevaluations of the family from the moral right.

The Brooks Debate

In an improbable piece for The Atlantic, conservative commentator David Brooks narrates the rise and fall of the American family with considerably less dread than one might expect. Brooks notes the social supports offered by the “corporate” family structure of the nineteenth-century, where multiple households supported a family business; and the subsequent decline of multi-generational habitation with the rise of an urban proletariat throughout the twentieth-century. Citing a middle-class cult of “togetherness,” Brooks correctly regards the nuclear family as an idealization, or an abstraction from a statistical average. The 1950s, Brooks declares, “was a freakish historical moment when all of society conspired, wittingly and not, to obscure the essential fragility of the nuclear family.”

Brooks, who for our purposes appears a better vulgar Marxist than Nagle, periodizes the decline of the nuclear family; marking a fall in real wages through the 1970s and a correspondent uptake in competitive individualism, alongside real gains in mobility for women by the feminist movement. (In this observation, he’s a better dialectician than Nagle, too.) Today, Brooks says, American marriage and birth rates continue to fall and the nuclear family seems on its way out. But this is only half the story. America, Brooks continues, “now has two entirely different family regimes.” Here Brooks winds up veering eerily close to the prognosis of The Communist Manifesto, where Marx and Engels declare that the bourgeois family, based on private gain, exists only for the bourgeoisie, while immiserating conditions have already abolished the family among proletarians. Now Brooks:

Among the highly educated, family patterns are almost as stable as they were in the 1950s; among the less fortunate, family life is often utter chaos. There’s a reason for that divide: Affluent people have the resources to effectively buy extended family, in order to shore themselves up. Think of all the child-rearing labor affluent parents now buy that used to be done by extended kin: babysitting, professional child care, tutoring, coaching, therapy, expensive after-school programs.

Brooks, like Nagle, cites Cherlin’s “marriage gap,” arguing that marriage is not only an amenity but an instrument of wealth. For moralists like Brooks, however, economic fortunes are an index of social behavior, and a secondary cause at best; and he’s quick to seek out sociological determinations of economic disparity, reading rates of divorce and remarriage as harbingers of poverty and very nearly parroting the Moynihan report’s foreclosure of Black sociality. The practical difference is in policy, where Brooks proposes a deemphasis of family life in favor of extended and experimental kinship structures.

“The good news is that human beings adapt, even if politics are slow to do so. When one family form stops working, people cast about for something new—sometimes finding it in something very old,” writes Brooks. Were the source concealed, one might almost agree. Surely politics trails actual developments within the lives of people, and the ways in which those lives are organized is nothing if not changeable. As Leacock explains, human beings only demonstrate a “potential for social living which cultural traditions then supply with specific goals. The notions of private property, or the monogamous family, are culturally learned goals.”11

In a series of anthropological overtures, looking to pre-capitalist and communal cultures throughout history and across the globe, Brooks strives to remind his reader that “throughout most of human history, kinship was something you could create.” This is doubtlessly true; though the recommendation is scarcely credible in Brooks’ voice, as a frontier mentality underwrites his canvassing of human custom writ large. Moreover, his account of the American family, however economistic, fails to apprehend the relations of production that subtend his broader thesis. Nothing about Brooks’ perspective is exemplary, except for its part in a broad consensus that the family isn’t working as one might expect.

The Lawful Structure of Love

In a response to Brooks, as part of an online symposium about his essay hosted by the Institute for Family Studies, Cherlin accuses sentimentality: large extended families form a nostalgic backdrop to a bygone way of life, he says, but rarely figured in the everyday; and those who have “innovated” their families outside of the white mainstream rarely did so by choice, and struggle in the present to repair conventional family bonds. All told, Cherlin opines on the side of natural law:

But one must recognize that forged families have some limitations. These kinship ties are easier to break because they are voluntary; neither strong norms nor laws stand in the way of ending them. They also take continual work to maintain: Although your sister is always your sister and your spouse is always your spouse, your close friend is part of your forged family only as long as you and she actively support each other.

This is a popular, and for many definitive, defense of the family bond, which takes on an ethical character insofar as it is both immutable and received. And yet, in setting forth their materialist determination of the family, Marx and Engels faced down an incredibly sophisticated version of this prejudice, in an account that forms a basis for many liberal defenses of the family today.

In his 1820 work, Outlines of the Philosophy of Right, G.W.F. Hegel characterized the loving family as the “immediate substantiality of mind”—a paradigm of individuality in essential unity with an external group.12 But even Hegel’s portrayal of the family as a social metabolism requires a moment of departure from this cozy interdependence, where the individual’s life within this group attains its meaning only when the group begins to dissolve. At this point, the family member in question sets out into the world; not as an act of secession but succession, to marry and recommence the cycle by which the family is “completed”—or, why not, abolished.

The act of marriage, Hegel continues, is a willed arrangement by which family capital is exchanged: “The family, as person, has its real external existence in property; and it is only when this property takes the form of capital that it becomes the embodiment of the substantial personality of the family.”13 In this description, free exchange motivates exogenous marriage rite, which market relation Hegel imbues with spiritual necessity, defining marriage as an ethical exemplum—a necessarily loving and conscious unity between consenting individuals. This subjective accord finds its objective unity in a child, to which both parties are absolutely obliged. One could always choose to end a marriage; but this new, dependant relation is non-elective, and thus forms a natural basis for social responsibility and property alike, as the objectification of the family’s intersubjective will.

Children are not property themselves, Hegel continues, but must be raised at expense of the family’s common capital until they reach self-subsistence and are capable of holding property of their own; in which case the dissolution of the family is nearly complete, pending inheritance on the death of the father. Regarding this transaction, Hegel is clear: “the essence of inheritance is the transfer to private ownership of property which is in principle common.”14 Hegel notes that certain earlier ideas of inheritance favored appropriation by proximity, insofar as death transforms private property into wealth without an owner, and the family was simply nearest to the deceased. This, however, “disregards the nature of family relationship,” which necessitates the transmission of property from generation to generation as a principle of ethical life.

In spite of his idealism, Hegel grasps the essential relationship between the family and private property, and the difficulty of accounting for family bonds outside of the latter logic. Here we can perform a simple Marxist manoeuvre and turn Hegel on his big head; for a re-historicization of bourgeois right—which extrapolates private property relations from personal embodiment and filiation—suggests that the custodial family models itself on private property relations, much as the productive family is a staple institution of an earlier feudalism. Moreover, the ethico-legal function of marriage in Hegel’s system models the calling of the authorizing state—to assuage an antagonism immanent to society itself.

Certainly, Marx and Engels oppose this metaphysical scheme in their demand for the abolition of the right to inheritance; otherwise, the redistribution in advance of lineal wealth allocation. But can the normative social function of Hegel’s family extend beyond the bourgeois property relations that it otherwise models? What, if anything, of this order might remain after the abolition of bourgeois right and property?

The Logical Structure of Love

In their work, Hegel and the Logical Structure of Love, philosophers Toula Nicolacopoulos and George Vassilacopoulos attempt to rewrite the account of familial love offered in the Philosophy of Right, in a manner that proves generative for a communist program of generalized care. As many rebuttals construe the family along similar lines to Hegel, as a timeless unit of ethical life, this work imagines other forms of objective solicitude, irrespective of sex, station, or relation.

Hegel’s description of familial love is based on an ideal unity, which may or may not be present in other intersubjective relationships. Altruism and solidarity, for example, needn’t recognize the particular individuality of the other; friendship proceeds without a public witness. If recognition is a crucial litmus, Nicolacopoulos and Vassilacopoulos argue, then the dynamic individuality that Hegel prizes is even absent from single-parenting, where the love of a parent for a child is initially asymmetrical; the child doesn’t recognize its self-unity in the parent as yet, and must move from undifferentiated identity with the parent to an atomic individuality before doing so.15 This insight is less disturbing than it sounds at first; for it only rejects the prospect of an unmediated ethical relationship. As noted above, the “single parent” exists only with reference to a double standard—nobody parents alone.

But what of marriage, the lawful relationship that culminates in the family? It’s true that the conceptual sacrament of marriage in Hegel is heterosexual, monogamous, dyadic; but its ethical necessity consists in loving and mutual consent. In Origins of the Family, Engels submits this implausible ideal to historical scrutiny, staging a dialectic of recognition; for where bourgeois property relations obtain, “the marriage is conditioned by the class position of the parties and is to that extent always a marriage of convenience,” if not outright captivity. Elaborating on a theme from the Manifesto—that in many respects, the family has already been abolished for the proletariat—Engels ventures that real mutual love can only exist amid the formal equality of the oppressed:

Sex-love in the relationship with a woman becomes, and can only become, the real rule among the oppressed classes, which means today among the proletariat—whether this relation is officially sanctioned or not. But here all the foundations of typical monogamy are cleared away. Here there is no property, for the preservation and inheritance of which monogamy and male supremacy were established; hence there is no incentive to make this male supremacy effective … The proletarian family is therefore no longer monogamous in the strict sense, even where there is passionate love and firmest loyalty on both sides, and maybe all the blessings of religious and civil authority.

Engels offers a historically specific definition of monogamy, as descended from property relations, that precludes the requirement of free consent. In this way, the disintegration of the family as a unit of production actually conditions love; though of course there are many other power differentials between people in a concrete situation, and in a patriarchal society marriage remains a point of access to a family wage. But Engels’ amoral claim by no means construes proletarianization as emancipatory in itself. One century later, John D’Emilio would ambivalently observe the correlation between “free labor” and free sexual association in a landmark essay on capitalism and gay identity, in an analysis that patiently attends to the domestic constraints placed upon women in the same conjuncture. These key materialist texts illuminate the difficulty of describing the family in terms of affective ties, and the impossibility of extrapolating affection from its legal sanction.

Nicolacopoulos and Vassilacopoulos understand the necessity of monogamy for Hegel, as “immediate exclusive individuality,” to denote the singularity of the beloved, where “exclusivity” denotes the relationship between a beloved’s attributes and their rare person, rather than a pact pertaining to exclusive use.16 This ingenious reading opens away from legalistic monogamy, affording ethical status to all manner of potentially concurrent relationships, but fails by the standard of property, where the institution of marriage presides over the distribution of economic benefit. But where the matter of family capital is concerned, Nicolacopoulos and Vassilacopoulos point out that Hegel defines family property as property that the family holds in common, that cannot be used by any family member in the capacity of the atomic individual. Truthfully, Nagle’s defense of the family as predictive of economic security, following Cherlin, is little more than a defense of this common property, to which empirical banality one must ultimately assent; it is better to have some wealth than none. But to expand the remit of the family beyond present recognition would surely change the meaning of collective wealth as well, including any protocol against the alienation of family property.

Most importantly, “although Hegel repeatedly invokes the biological family … he does not conflate this with the source of the ethical bond between parents and their children,” Nicolacopoulos and Vassilacopoulos and explain. Rather, “the ethically significant relationship between parents and children concerns the ‘second or spiritual birth of the children,’” namely their upbringing.17 Parenting for Hegel is ethically imbued because it has the negative aim of raising children out of instinct into the freedom of personality, beyond which Hegel offers no instructions or prescriptions as to the cultural situation or particulars of parenting. Thus the Hegelian approach of Nicolacopoulos and Vassilacopoulos “can recognise people sharing responsibility for raising children with a wider circle of intimate others. What matters for the ethical significance of parenting is whether or not those raising the children are related to each other and/or to the children through their mutual loving feeling.”18

Against heteronormativity—and an inconsequential homonormativity sourced from the reifications of queer theory, which seeks a universal figure of desire in historically proscribed behaviors—Nicolacopoulos and Vassilacopoulos recommend a social fabric of “multiple loving forms.” Where Cherlin’s churlishness is concerned, it suffices to say that his thinking is entirely constrained by a society based on generalized self-interest and competition. One needn’t believe in an alternative, nor in the possibility of change; but then one needn’t be a Marxist, either.

Old Habits

In 1920, Soviet feminist Alexandra Kollontai wrote extensively on the family for the journal Komunistka, or ‘The Woman Communist.’ Kollontai stages the question directly:

Will the family continue to exist under communism? Will the family remain in the same form? These questions are troubling many women of the working class and worrying their menfolk as well. Life is changing before our very eyes; old habits and customs are dying out, and the whole life of the proletarian family is developing in a way that is new and unfamiliar and, in the eyes of some, “bizarre”.19

Noting the oppression of women within the traditional family, who are obliged to domestic labor and increasingly subject to the necessity of waged work outside the household, Kollontai observes that the family as a unit of production is disaggregated by capitalist expansion: “The circumstances that held the family together no longer exist. The family is ceasing to be necessary either to its members or to the nation as a whole.”20 Kollontai doesn’t simplistically bemoan this decline or superfluity, in which the family appears as an archaic form of organizing and disciplining labor, but presses further in observation of the historical character of this organization. The family is principally charged with education, in the Russian case; rather than expand this function, Kollontai wonders if it can’t be relieved of this task as well, envisioning the end of housework and domestic hierarchy.

As the individual household ceases to be productive, greater demands are to be made of the state; and Kollontai describes this movement in the precise terms of socialist transition. “Just as housework withers away, so the obligations of parents to their children wither away gradually until finally society assumes the full responsibility.”21 Kollontai’s subsequent proposals for dividing childcare in the service of “solidarity, comradeship, mutual help and loyalty to the collective,” and to overcome the strictures of “the old family, narrow and petty, where the parents quarrel and are only interested in their own offspring,” would surely scandalize readers of The Lamp every bit as much as Nagle’s lurid paraphrase of more recent, ultraleft opinion against the family.22

Yet Kollontai deals with the two facets or temporalities of family transformation that Nagle conflates—abolition and decline—as part of a movement: “There is no escaping the fact: the old type of family has had its day. The family is withering away not because it is being forcibly destroyed by the state, but because the family is ceasing to be a necessity.”23 To this way of thinking, the family is not destroyed by voluntarist deviancy, but in the same way that any culture opens itself to change in an orthodox Marxist description—insofar as its private remit enters into a contradiction with increasingly socialized production. Kollontai consoles the caring parent:

Working mothers have no need to be alarmed; communists are not intending to take children away from their parents or to tear the baby from the breast of its mother, and neither are they planning to take violent measures to destroy the family. No such thing! The aims of communist society are quite different. Communist society sees that the old type of family is breaking up, and that all the old pillars which supported the family as a social unit are being removed: the domestic economy is dying, and working-class parents are unable to take care of their children or provide them with sustenance and education. Parents and children suffer equally from this situation.24

In a recent summary of Marxist thinking on the family, Alyson Escalante reminds the reader that Kollontai, like Marx, “points to capitalism’s own destruction of the family among the workers” as proletarianization proceeds apace. Moreover, Escalante notes, Kollontai writes to counsel the necessity of change, not a program of abolition per se, where capitalism has already weakened, and perhaps destroyed, the productive substrate of the family. Because of this insight, Kollontai’s hundred-year-old words can help one to imagine an objective and affective future for innumerably many loving, fighting forms. As Escalante writes:

In the face of the capitalist destruction of the role of the family, (Kollontai) simultaneously argues that attempts to hold on to the old family are both doomed and also naturalize women’s subordination, while simultaneously insisting that a new type of family is possible. She does not tell concerned workers that they must suck it up, that their fears are reactionary and that they must embrace a world without the family. Rather, she preserves the language of the family but reinterprets it into a collectivist, that is to say, a communist, version of the family. The old family is dead, capitalism has killed it, and so we have been invited to build and define a new family.

Family Borders

This is a powerful reply, if not to Nagle and to Brooks themselves, then to the conditions that they differently, and partially, address. While Brooks’ thought experiment attempts to recompose the American social fabric after the fashion of a corporation, he fares considerably better than Nagle in observing the necessity of change. Faced with the specter of collectivism, Nagle taunts: “but where will the village, this hypothetical replacement network of solidarity that will recreate and even improve upon the intense loyalty and selfless caregiving of parents and their children in the family unit come from?” One might suggest that this network will necessarily come from those parents and children whose fortunes require a total transformation of society, but that would be only too logical. As Nagle refuses to see communal supersession as a solution to, rather than a cause of, the objective decline of the bourgeois family, she misapprehends the bearing of its discontents. The support network that Nagle disparages is already immanent to the crisis of the family—which is only ever a crisis of capitalism, shored at home—and her language of “replacement” alludes to a different set of anxieties altogether.

Nagle’s unsuitable nostalgia for a recent period of social cohesion, shored in the miniature family as a bulwark against social chaos, is perhaps too typical of the American left, though her conservatism is near-total:

Nobody would have believed just a few months ago that, say, abolishing the police would become a tenet of mainstream American liberalism. Even rightwing politicians have been cowed more or less overnight into publicly agreeing with things beyond the wildest dreams of the most radical anarchist of just a few years ago. If the abolition of the family is the next demand of our successful cultural revolutionaries, it is easy to imagine how the legal infrastructure undergirding could be dismantled; its moral and cultural foundations are already vulnerable old structures just waiting to be tipped over. Who exactly is going to stop them?

Who, “exactly,” does this call intend to summon to the family’s defense? Nagle’s culture war proceeds on many fronts, and it’s certainly handy that she can’t turn in a 1500-word screed on the family without calling the police. But an inventory of her various journalistic stunts paints a fairly clear picture of her ideology. The cause of the American family has facilitated racial and sexual panic for more than a century, and unspecified concern for the health of “the family” as a reproductive project has long been a polite expression of anxiety over racial purity and demographics.

In The Left Case against Open Borders, an execrable piece from 2018, Nagle punches left again. Here Nagle argues that “open borders radicalism ultimately benefits the elites within the most powerful countries in the world, further disempowers organized labor, robs the developing world of desperately needed professionals, and turns workers against workers.” Almost clause for clause, this sentence does the work that it attributes to irrational radicals, pitting workers against one another to the benefit of the ruling class. At any border, the contradiction between capital and labor means a relative porosity for capital flows and increased brutality and scrutiny for migrants; and an international division of labor is responsible for the domestic fortunes of a country’s working class in any case.25 “But the Left need not take my word for it,” Nagle gloats. “Just ask Karl Marx, whose position on immigration would get him banished from the modern Left.”

Nagle’s staggeringly incorrect reading of Marx quotes from a letter regarding the division of English proletarians and Irish proletarians: “The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself,” she recites. It’s difficult to enumerate the errors in thinking here. Where Marx sees a process of ethnic scapegoating, obscuring the true contradiction of labor and capital, Nagle chooses to see a contradiction between national interests, and her own racism is clear from her abuse of this citation. In the letter quoted above, Marx goes on to compare this divisive scenario to the enmity of “poor whites” for former slaves in the United States, anticipating W.E.B. Dubois’ description of whiteness as a “psychological wage,” preventing white workers from practicing solidarity by conferring public and legal benefits beyond simple remuneration.

It’s worth noting that there’s almost no chance that Nagle was familiar with Marx’s argumentation on this matter before seeking recourse to his authority. Rather than cite Marx’s 1870 correspondence with Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, in which this passage appears, Nagle’s bibliography points to an article by David L. Wilson, in which he quotes from Marx’s letter in order to make a very different argument. Wilson notes Marx’s assertion that Irish immigration precipitated a reduction in English workers’ wages—before theorizing the ideological utility of this national division for the ruling class, one might add—but is careful to note how racism and xenophobia create the climate in which migrant laborers face lower pay and worse conditions of work, putatively forcing wages down. The problem, Wilson concludes, is exploitation, not immigration.

Nagle’s national chauvinism is intimately related to her defense of the family; for closed borders and private families are two means of attempting to ensure the homogeneity and mores of a population. In Kill All Normies, Nagle portrays the online “alt-right” as a negation of the family-values conservatism evolved by pundits such as Pat Buchanan in the 1990s, which characterization both exaggerates the novelty of this phenomenon and paves the way for a rehabilitation of family values from the left. But as Sophie Bjork-James shows in her research into white nationalist web forums, the family is a central occupation, even a primary concern, of today’s online and alternative right:

Over the past few decades, changes in economic conditions and gender norms have created a proliferation of new family forms, further destabilizing the nuclear family—changes that effectively reduce the space of patriarchal power and disrupt the perceived division between personal and economic life … These conservative and racist activists fight to restore a model of the family, race, nation, and economy that has lost its hegemonic status.26

Bjork-James ventures a determination that eludes Nagle, where the family functions for its staunchest defenders as a fantastic unity beyond the economy and state, despite its historical existence as an expression of both. Ironically, it’s because of Nagle’s crude “class reductionism” that her economic analysis bottoms out at the usual racist canards—“cheap illegal labour,” “single parents,” and so on. Nagle attributes declining economic fortunes to the same scapegoats as the right—once an ethnographic quarry, now her preferred company.

Fordism and the Family Wage

For all of her dalliances with the right, it’s crucial to note that Nagle’s merely reflexive arguments have far more rigorous, if rigorously reactionary, precedent on the chauvinist left. One could look to sociologist Wolfgang Streeck, for example, whose grim assessment of the postwar welfare state was influential in the 2018 formation of Aufstehen, a German political coalition of “the materialist left, not the moral left.” Like Nagle, Streeck has a record of xenophobic invective, accusing refugee and asylum policy of serving elite interests by importing a foreign labor reserve.27 Streeck takes a special interest in the family, too—annotating its transformation after the decline of American industrial occupation in the postwar era, and the relative safety net extending from the factory to the father to his dependents. According to Streeck:

The social and family structure that the standard employment relationship had once underwritten has itself dissolved in a process of truly revolutionary change. In fact, it appears that the Fordist family was replaced by a flexible family in much the same way as Fordist employment was replaced by flexible employment, during the same period and also all across the Western world.28

Such an account offers the periodizing detail that Nagle omits. But Streeck also laments the disappearance of jobs from core capitalist countries at the same time as he divides the working class by national origin; thus his account of family “decline” is both tellingly chauvinistic, and elucidating in overlay. According to Streeck, “intensified commodification of labor, in particular the increased labor market participation of women, and the de-institutionalization of family relations,” are key factors in the decline of fertility in advanced industrial countries and not others.29 Political scientist Melinda Cooper calls attention to the apparent sexism of this description:

It was feminism, after all, that first challenged the legal and institutional forms of the Fordist family by encouraging women to seek an independent wage on a par with men and transforming marriage from a long-term, noncontractual obligation into a contract that could be dissolved at will. In so doing, feminists (whom he imagines as middle class) robbed women (whom he imagines as working class) of the economic security that came from marriage to a Fordist worker. By undermining the idea that men should be paid wages high enough to care for a wife and children, feminism helped managers to generalize the norm of precarious employment and workplace flexibility, eventually compromising the security of all workers.30

One ought to note the parallels between Streeck’s account of the flexibilized family and his characterization of the welfare state destabilized by rapid demographic change, in which he describes European immigration policy as an executive adjustment to wages and employment opportunities for domestic workers, enacted after the progressive desires of “liberal-cosmopolitans.” In broad strokes, Streeck’s sketch of the post-Fordist dissolution of the family implies an infiltration of the national economy from within—a domestication of the national economy transpiring in tandem with the global operators of deindustrialization. As with his disparaging remarks about the role of multiculturalism in economic deregulation, Streeck’s paranoia leads him to non-dynamically assert the leading role of culture in the family’s transformation:

Cultural change—the spread of non-standard forms of social life—may have paved the way for economic and institutional change, in particular the rise of non-standard forms of employment, with the deregulation of society as a forerunner to the deregulation of the economy … Clearly, the decisive development in this context was the mass entry of women into paid employment, which eventually came to be celebrated across the political spectrum as a long-overdue liberation from servitude in the feudal village of the patriarchal family. Especially for the liberal wing of the rapidly growing feminist movement, the associated increase in economic uncertainty and social instability appeared to be a price worth paying for what was seen as secular social progress.31

Streeck glancingly counters his own hypothesis with a more substantive claim—that a decline in real wages might have forced more members of a given household into the workforce in order to support their middle-class standard of living, for one—but doesn’t really attempt to mediate these two perspectives. As one should understand, social movements do not emerge under conditions of the participants’ choosing; and the abatement of the family organization isn’t a revenge fantasy of its feminized discontents. By Streeck’s account, incorrigible women en masse appear too covetous of precarity to recognize that they are about to destroy the patriarchal family wage, of which they are the foremost beneficiaries.

In the post-Fordist Genesis of Streeck’s simplifications, it seems inconceivable that women could make political demands upon capital, for liberation from the household, or for a subsequent social wage. Notably then, even though his own politics offer no greater destination than the recent past, Streeck already sees this post-Fordist deregulation of the family culminating in a paradoxical redistribution of responsibility. Streeck observes a trend toward the socialization of reproduction in a number of countries, including free childcare and wages for stay-at-home caregivers—and compares this to a shameful situation in the United States, where single parents have fewer real supports than any core capitalist country.

New Poor Law

When Nagle cites the outcomes of single parenting in North America without any reference to the paucity of available resources, she imputes the violence of the state to proletarian parents, exaggerating and denying their agency all at once. This is a fairly standard manoeuvre, that construes systemic obstacles as failings of personal morality. In its perfected form, this ideology makes moral demonstration into a condition of social support; which is, in broad strokes, exactly how the American welfare system was rearticulated during periods of neoliberal restructuring. Thus, as Melinda Cooper explains, broad neoliberal reforms in the period following the collapse of the Fordist paradigm sought to resuscitate a kind of poor law, emphasizing marital responsibility and familial relation as crucial institutions of economic security, apart from the welfare state.

This powerful ideology justifies the low participation of the United States government in social assistance programs, as observed by Streeck. But for all of his cultural fixations, Streeck’s empirical comparison between American and European data sets omits crucial mediations of data. The crisis of the 1970s was a crisis of the racial state, writes theorist M. Jacqui Alexander, in which “poverty had to be colored black”; and the reconstructed welfare system that emerged from this decade further entrenched this expectation. This era’s debates fixated on the issue of single parents, “as a way to animate state policy and mobilize a manufactured popular memory that made (black) poverty the causal derivative of welfare.”32

Cooper observes the special scrutiny reserved for federal assistance programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which was accused by the conservative left and the right alike of “undermining the American family and contributing to the problem of inflation.”33 This program comprised an important arm of the new poor law, establishing a state chaperone of ruthless prurience—“man-in-the-house” rules, for example, permitted random home inspection to determine whether or not a program participant was in a sexual relationship with a man. If they were, Cooper explains, benefits were revoked, as the male houseguest was deemed “a proper substitute for the paternal function of the state.”34 In this respect, the new liberal welfare regime and its flagship programs functioned as the precise obverse of the Fordist family wage system—presuming male attendance to betoken financial stability. In this lawful arrangement, Alexander says, the state assumes the position of “white fathers to blackness,” recalling the “memory of secret yet licit white paternity under slavery and its possible vengeful reemergence at a different historical moment.”35

As both Cooper and Alexander discuss, the AFDC program proved especially controversial for its perceived benefit to single Black mothers at public expense, even though it was relatively inexpensive among social security programs and the majority of recipients were white. Where the paternal function of the state is concerned, Alexander diagnoses a conservative moralism according to which “it was an irresponsibly absent black masculinity that made the potential conjugal couple incomplete and shifted the fiduciary obligations of the private patriarch onto the public patriarch, thereby forcing an uncomfortable and unwanted paternity onto the white public patriarch.”36 With this dynamic in mind, conservative attacks on single parents appear less a matter of superior morality than an ironic disputation of responsibility, historical and present.

Democrats and Republicans alike accused the AFDC program of fostering dependence on state support, even though benefits had declined precipitously since 1970; and AFDC was replaced with the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWORA) by President Bill Clinton in 1996. PRWORA replaced AFDC with a highly conditional program called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), offering benefits at approximately one-third of the poverty level; and proliferating conditions that were found to contravene human rights, even permitting states to withhold benefits from mothers who can’t identify the biological father of their children. In this respect, Cooper suggests, PRWORA is both precedent-setting and paradoxical—using the conservative sacrament of the heterosexual family to pursue a radical neoliberal agenda of atomized personal responsibility.

The “ideological blackening of welfare,” Alexander says, also adversely affects other racialized groups. She calls attention to the “ideological proximity between PRWORA (and) the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act also of 1996,” which work at once to “make welfare, labor, and immigration deeply intertwined.” Here Alexander follows the work of Payal Banerjee:

Banerjee argues that the state derived support for PRWORA from the widely held belief that “illegal” and “legal” immigrants relied on state public support and that prohibiting immigrants from receiving public assistance would act as a powerful deterrence to immigration. As a result, both “legal” immigrants (noncitizens) and “illegal” immigrants became ineligible for certain provisions under PRWORA.37

Weighing the Anchor

This complicated saga of targeted racism, massive deregulation, and misogynist stricture forms the basis for Nagle’s assertions as to the non-viability of single-parent homes and the apparently poor outcomes of non-patriarchal care. These are the family values that Nagle defends—a mercenary hodge-podge of spiritualized economic precepts, essentialized market relations, phobic prohibitions, and paranoia. It goes without saying that families of all kinds are places of intense care and devotion, among many other things; but that guise is ultimately incidental to Nagle’s rallying cry, where she knows very well that it is not being criticized by Marxist feminists for any of those occasional features. As noted above, the ethical dimension of family life is itself contingent, consisting of a collective life that can even help to envision its historical transformation.

The family is not only a historical phenomenon, subject to alteration; but as Bjork-James notes, can also serve as “an anchor of stability in a time of increasing economic and social change.”38 At its most constructive, Nagle’s argument tends to nostalgia for mid-century conditions of capital accumulation, in which sweeping and systemic exclusion procured limited security for a politically enfranchised section of the working class and their preordained dependents. This is a Trojan horse for racism and xenophobia—MAGA with medicare, to be blunt.

Where the family is an obvious synecdoche of nation, Nagle’s convenient narrative of its decline dovetails with her isolationism. This is a unified position, and a fascist one; such talking points have always traveled by way of a superficial socialist concern, and aren’t difficult to spot in their enthusiasms and vendettas. One might even ask whether Nagle herself is worth the trouble. But arguments like hers prove oddly persuasive in certain socialist circles. The Class Unity subgrouping of the DSA, who profess a materialist Marxist politics, enthusiastically promoted Nagle’s article on social media, for example; and her prejudices mirror those of a “traditional left,” characterized by Donald Parkinson as “socially conservative, economically leftist.” As the meaningless abstraction of “populism” tempts a back and forth traffic between these conventional poles, it is more vital than ever to insist upon the Marxist legacy of abolition; “to find the new world through criticism of the old one,” one might say. For communists don’t rally to the recent, nor the distant, past. Our real descendancy is in a better future—one in which family chauvinism, white supremacy, and class privilege are given to history in their entirety.