Donald Parkinson weighs in how communists should relate to our difficult history. We can neither be in denial of our failures or refuse to own up to them.

As communists living in the aftermath of the 20th century, we inherit a legacy that is tainted by violence and corruption. This legacy is haunted by misfortunes that we rightfully wish to distance ourselves from. Yet we are inevitably attached to it, regardless of how much we denounce it. It is not only the name of ‘communism’ that is associated with the crimes of Stalin, the images of Soviet ‘totalitarianism’, and the arbitrary violence of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Any grand attempt to change the world in the name of universal humanity and do away with the regime of private property carries these associations. The legacy of communism as a mass social project, not merely an idea, is tainted by a difficult past. To simply find a new name or symbolism as a way to distance ourselves from the legacy of brutality associated with communism will not work; we carry this legacy regardless of our appearance.

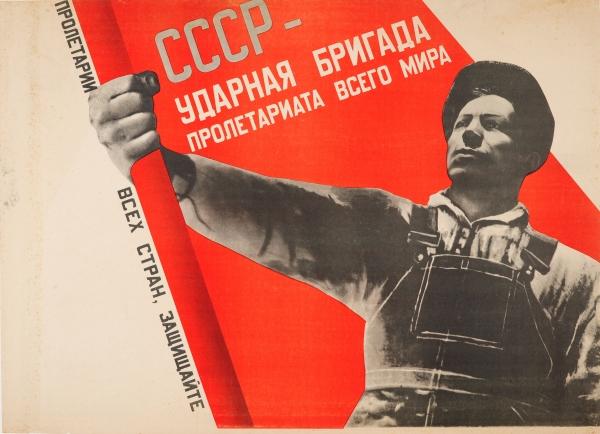

Lucio Magri calls this legacy “the burden of communist man” when discussing the Italian Communist Party. Magri used this term to discuss the contradiction of the party seeking legitimacy as a mass movement that stood for all that was progressive and democratic, while at the same time existing in continuity with the Stalinist purges and famines. When the Italian Communist Party reasserted itself after WWII, the Soviet Union was still standing, holding a well-earned reputation as a symbol of mass resistance to fascism. The Cold War had only recently begun, and anti-fascism was a more potent force than anti-communism. Today we live in a world of hegemonic anti-communism, where the notion of ‘totalitarianism’ tells us that communism and fascism were just two different expressions of what terror awaits us if we diverge from the liberal-democratic norm.

In spite of the hegemony of anti-communism, many of us are seemingly immune to it. We cannot help but be captivated by the idea that the world we live in must be changed at a fundamental level. The world must be remade, not reformed; history must be something that we consciously make, not passively observe as its victims. We are believers in a god that failed, defending what much of the Western world sees as a lost cause. Perhaps some of us may be attracted to such a vision for reasons of pure revenge fantasy, yet for the majority of us, it is a moral search for justice that makes communism compelling. Regardless of our intentions, there is an element of faith in our convictions. Rather than acting as an economically rational unit that seeks the most advantageous utility out of their current circumstances, the dedicated communist acts against what is convenient. Yet this faith is different from superstition; it is rationalized with an analysis that aims to be scientific, drawing from all human knowledge to create an all-sided worldview based in reason. This is well and good, but no matter how much we try to weigh our views with evidence it ultimately requires a leap of faith, a wager of sorts, to immerse oneself in the conviction of a communist future. Lucien Goldmann described this faith as follows:

Marxist faith is a faith in the future which men make for themselves in and through history. Or, more accurately, in the future that we must make for ourselves by what we do, so that this faith becomes a ‘wager’ which we make that our actions will, in fact, be successful. The transcendental element present in this faith is not supernatural and does not take us outside or beyond history; it merely takes us beyond the individual.

We can tell ourselves all we want that we are merely inspired by an objective analysis of the impossibility of capitalist development after a certain historical breaking, only cold observers of the need for the forces of production to develop beyond the limitations set upon them by the irrationalities of the market. We would, of course, be right, yet to actually dedicate oneself to act upon this analysis requires a willingness to act beyond the confines of the self, beyond the immediate comfort of our lives. We must make a prediction, or wager on a future that we can never be one-hundred-percent sure of regardless of how refined our analysis is. Lars Lih argues that Lenin’s choice to seize power in 1917 was based on these kinds of wagers, the most important one being that the international working-class would follow his revolution in solidarity and spread it across the world. There was no way to make such a prediction with absolute certainty, yet Lenin’s faith in the communist future allowed him to act on such a wager and carry through the task of revolution. Faith in the communist cause is essential to give us the conviction and militancy needed to make sacrifices for a greater goal, especially when faced with times like the ones we live in.

So how does one carry faith in Communism to this day, regardless of the burden of the past that we carry, the burden of communist man? How do we convince ourselves and others to make the wager that communism is possible, despite the tumultuous history behind us? Regardless of our moments of triumph and victory, there are still moments of genuine failure and atrocity. We are reminded of them constantly by the media and our social circles outside communist militancy, who see them as obvious reasons to write off communism and move on. My aim here is not to discuss these particular tragedies and crimes, but to discuss what kind of attitude we should have when looking upon the past and discussing it. First, we shall look at the common paths that people take in response to these issues and why they are inadequate.

One path commonly taken is denial. Denial means blinding oneself to any of the negatives in our past. If there are tragedies, it is the collapse of the USSR (caused entirely by external rather than internal forces) or the cases of outright violent capitalist counter-revolution. For more complex events, where communists faced repression from other communists, those who take the path of denial develop bizarre conspiracy theories or simply dismiss any kind of concern as capitulating to propaganda. The Moscow Show Trials, in which the Bolshevik elite were purged on absurd charges of aiming to unite with global fascism to overthrow a state they had helped to forge, are entirely justified in this view. The confessions extracted from the likes of Bukharin and Radek are seen as completely genuine. The best-known proponent of this view is Grover Furr, a Medievalist professor who claims that Stalin committed no crimes, in works such as Khrushchev Lied.

The path of denial is not an option, and those who take this path, regardless of their intentions to challenge the dominant hegemony of propaganda, only barricade their faith in the communist cause with the delusion that their own team was incapable of doing wrong. It rests on superstition rather than a reasoned faith in the final goal of communism. This is not to say that we shouldn’t defend even the most flawed figures of our history from bourgeois lies, even at the risk of sounding like apologists. There is no doubt that death tolls have been inflated and responsibilities placed in unreasonable ways when the bourgeoisie discusses the history of communism, and the authentic historical record must be defended. The danger is that in this defense, we lose sight of the actual crimes committed under our flag, and simply become contrarians to the mainstream history.

A more reasonable variant of the path of denial is to point out the hypocrisy of bourgeois hype over the crimes of communism, exposing their double standards of condemning the crimes of communism while apologizing for their own. This perspective, best articulated by the now-deceased Domenico Losurdo, is often described as “whataboutism” for its attempt to deflect the crimes of communism onto the crimes others. This perspective in its more nuanced forms does reveal profound hypocrisy at the heart of the bourgeois project. After all, if we apply the standards that liberals use to judge communism, we must also reject capitalism. Yet if we are consistent, shouldn’t we also condemn communism? At that point, we are left only with a vague desire for a “third way” with no basis in history, a rejection of any possibility for a better future. The only possible conclusion is to accept the flawed nature of humanity and engage in some kind of individualist rebellion against society itself.

The approach of ‘whataboutism’ also falls under denial because it refuses to recognize that Communists must have a greater moral standard than the bourgeoisie. Many Marxists would argue that morality is a meaningless concept that serves no purpose for a communist, a mere ideological fetishism used to justify bourgeois property relations. It is true that morality does not exist independent of the class divisions in society. Yet it was for a reason that Engels spoke of Communism as moving beyond “class morality” towards a “really human morality which stands above class antagonism …at a stage of society which has not only overcome class antagonisms but has even forgotten them in practical life.” We must not be moral nihilists, but rather prefigure this “really human morality” in the socialist movement itself, while also understanding that it cannot exist in a pure and untainted form. So while it is of value to point out the moral hypocrisy of anti-communists, it is not enough. We must also have our own moral standards. This does not mean moralizing, to simply apply abstract moral ideals absent any material analysis of the concrete situation in its historical circumstances. As Leon Trotsky said, “In politics and in private life there is nothing cheaper than moralizing.”

On the other end, there is the path of distancing. This is summed up in a phrase that has become a joke amongst liberals and right-wingers: “that wasn’t real communism.” Those who take this approach would deny that the various crimes committed under the red flag can even be called our own, that they were deviations completely foreign to authentic communism. All that is undesirable in historic communism is placed under the label of “authoritarian socialism”, counterposed to an ideal “socialism from below” that has never been achieved. The impulse to distance oneself from the checkered history of communism, to insist that it has nothing to do with the true meaning of communism and what we want to achieve, comes from a genuine moral instinct towards universal human emancipation from all oppression regardless of its form. Yet condemnation of communist crimes by communists still doesn’t change the reality that we inherit this history. No matter how much we deny this, the majority of the public sees the crimes of Stalin as part and parcel of the communist experience, as part of projects that authentically aimed to build an alternative to capitalism.

Distancing typically takes a completely moral route, starting from an abstract opposition to authoritarianism and rejecting any kind of hierarchy in an a priori value judgment. This naturally entails condemning ‘actually existing socialism’ for the existence of any kind of impurity. An example of this kind of thinking can be found in an essay by Nathan J. Robinson, How to be Socialist Without Being an Apologist for the Atrocities of Communist Regimes. Robinson argues that countries like Cuba and the USSR tell us nothing about egalitarian societies and their problems, only authoritarian societies. Because communism is a society without classes or the state, and the USSR fails to meet this ideal type, no real conclusions about communism can be drawn from the USSR. In fact, Castro, Mao, Stalin, and Lenin didn’t even try to implement these ideas because their own ideology wasn’t pure enough, an “authoritarian” form of socialism rather than a “libertarian” one. Communism is an ideal that has no real-world reference point, except books where the ideas are held. All we have here is a moral opposition to hierarchy and authority that makes any serious historical investigation and reckoning superfluous.

Some communists attempt to frame their act of distancing in more theoretical, not merely moral, terms. Some argue that socialism has never been attempted in ideal circumstances, only in developing countries without a fully consolidated capitalist base. As a result, all that could develop is a form of “oriental despotism” or “bureaucratic collectivism”. While it is true that socialism will be easier to develop where capitalism has more fully taken hold, what we must keep in mind is that politics never occurs in “ideal circumstances”. Socialism will never exist in a vacuum, away from all the muck of the past and imperfections of human experimentation in the present.

Others would deny that socialism was even attempted. These are the theorists of ‘state-capitalism’ like Tony Cliff, Raya Dunayevskaya, and Onorato Damen, who held that the USSR and its offshoots were just a different form of capitalism, one where the state was a single firm and the entire population waged laborers. There are many problems with state-capitalism as a theory. It takes the surface appearance of the USSR as having commonalities with capitalism without looking deeper into the actual laws of motion in these societies and how they correlate. For Marx, capitalism is a system based on the accumulation of value, where firms compete to exploit wage labor as efficiently as possible and sell their goods on the market. Prices of goods manufactured in mass factory production are supposed to gravitate toward the socially average necessary labor time to produce the goods. This process is known as the law of value. In the USSR, prices were determined by state planning boards, used as a rationing mechanism of sorts. Other tendencies that defined capitalism, such as the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, were also missing. This is only scratching the surface of state-capitalist theories, but it should be clear enough that there are strong objections to these understandings of the USSR and ‘actually existing socialism’.

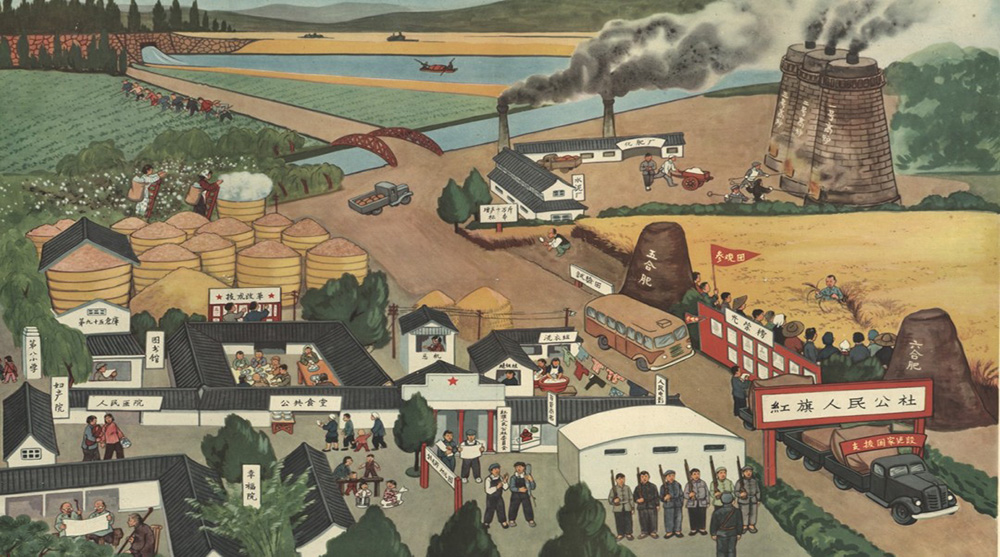

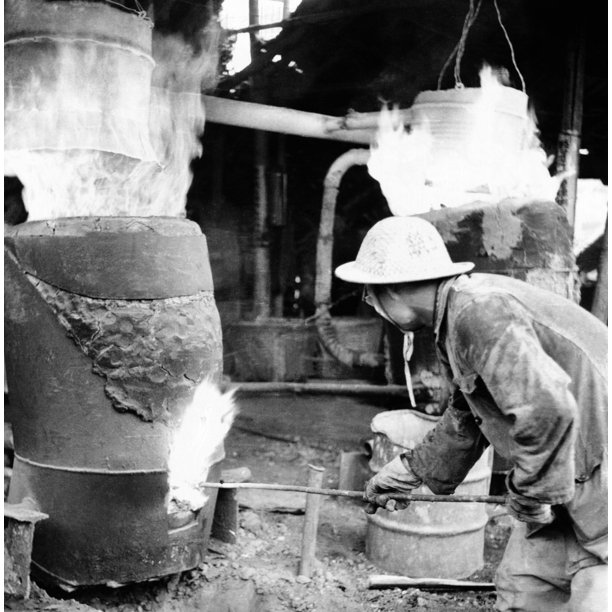

Attempts to distance oneself from the experience of ‘actually existing socialism’ by writing it off as just a form of capitalism to oppose like any other is also a form of denial, as well as distancing. It is a form of denial because it aims to avoid reckoning with the fact that these were attempts at building socialism, genuine attempts to create a society outside capitalism. Denying this lets us dodge having to genuinely come to terms with their failures. The USSR, Maoist China, East Germany, and others were all societies that attempted to replace the ‘anarchy of the market’ with state planning, replacing the production of exchange values with the production of use-values. It is arguable whether they are worthy of the title of socialism (I wouldn’t use it without qualifiers), yet to deny that they were related to a project of building socialism is untenable. The act of distancing is an attempt to wash one’s hands of the burden of communist man, which gives moral solace to the individual but fails to actually assess the difficult reality of the past. In this sense, it is a communist faith that is rooted in superstition as much as any other denialism.

Given the inadequacy of either denialism or distancing, the question of how we appropriately address our past remains. For one, we must own our past. Any kind of cowardly attempt to proclaim that we have no relation to the actual history of communism should be rejected. That there is a past of bloodshed (as well as triumph) that we inherit is something we must come to terms with. By taking responsibility for our past we disallow ourselves from making any simplistic assumptions that “true communism” was never tried, and that with our own purity of ideology we will do right. Instead, we must make an honest assessment of the actual history, understand the actual failures and recognize the kernels of the communist futures that manifested in the processes of the historical socialist project. This approach, neither denial nor distancing, is what I call the balancing act.

This approach was attempted by Leon Trotsky, a thinker, and leader who undoubtedly stands in the pantheon of great revolutionaries, despite many imperfections. The organizational legacy of Trotsky’s Fourth International is one marred by sectarianism and delusions of grandeur, as seen in countless Trotskyist organizations today, all fighting over who carries the true legacy of the man. Trotsky’s own thinking could be distorted by economism and his own career was not without opportunism and excess. But this is not the place for an in-depth critique of Trotsky, as much as it is warranted. What interests us in Trotsky is what his own approach to the problems of the USSR (a society he helped create yet found himself exiled from) can tell us about how to relate to our past in a critical way.

The most important aspect of Trotsky’s work, besides the concept of uneven and combined development, was his critique of the USSR. Trotsky’s own theory of the ‘degenerated workers’ state’ is of course not without flaws. The notion that the origin of bureaucratization in the USSR was the kulak when the Stalinist bureaucracy would go on to engage in a vicious assault on the kulak can hardly hold up under too much scrutiny. What makes Trotsky’s analysis valuable is its capacity to vigorously critique the USSR while maintaining that it was a conquest of the working class that needed to be defended at all costs. It is within Trotsky’s way of understanding the USSR that we can find a correct way to understand our past. Perry Anderson described this as a sort of “equilibrium” between defense of the ‘workers state’ and critique of its bureaucratic degeneration:

Trotsky’s interpretation of Stalinism was remarkable for its political balance – its refusal of either adulation or condemnation, for a sober estimate of the contradictory nature and dynamic of the bureaucratic regime in the USSR…There is little doubt it was Trotsky’s firm insistence – so unfashionable in later years, even among many of his own followers – that the USSR was in the final resort a workers state that was the key to this equilibrium.

As Anderson points out, this equilibrium between “adulation or condemnation” was a treacherous one. To move too much in the direction of condemnation would be to take that risk of playing into the hands of the capitalist who condemned the USSR and used its shortcomings to bury the project of communism, and rally military intervention against it. This road was exemplified by the path of Max Shachtman, who would argue that the USSR under Stalin had become a form of ‘bureaucratic collectivism’ that was actually regressive relative to capitalism, due to its lack of civil liberties. This led him on the path of eventually lending a helping hand to Western imperialism in the Cold War, believing the US and NATO were genuinely more progressive for the working class. The logic of this approach led to saying that the USSR’s collapse would be a progressive win for the international proletariat because it would sweep away the totalitarian system repressing the liberty and freedom that represented genuine gains of bourgeois society. Today Shachtman’s followers in the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty celebrate the collapse of the Soviet Bloc as a victory of socialism despite the massive human cost. Hillel Ticktin, whose analysis of the USSR contains many useful observations, falls into a similar trap. While Ticktin never supported imperialism, he did state that “given the lack of understanding of what the Soviet Union was and the influence of the Soviet Union in preventing the coming into existence of a genuine socialist party, the end of the Soviet Union was a step forward.” One would think that this “step forward” would be accompanied by a renaissance of Marxism and worker organization, not neo-liberal shock therapy and reactionary nationalism.

It is not necessary to fully agree with Trotsky’s analysis of the USSR as a workers’ state, albeit degenerated, to accept that the USSR had certain advantages for the working class that were lost with its collapse. Coming to understand this is essential if we want to adequately comprehend the past communist experience. Michael Lebowitz argues that in the USSR there was a “tacit social contract” that “provided direct benefits for workers.” This was not a social contract based on the direct rule of the workers over the conditions of their own existence. It was a system where workers were still atomized, unable to exercise collective control over production. They were organized in official trade unions and civil society organizations without being able to form their own independent organizations. However, in exchange for yielding these freedoms, citizens of the USSR were able to receive protection from unemployment and guaranteed access to subsistence in an informal pact with the party-state. The nationalization of practically all private property allowed the USSR to “shield” itself from the forces of global capitalism and carve out space to form its own economic dynamics, protecting its citizens from the chaos of the market. This meant workers genuinely had something to lose in the form of a package of economic rights, given in exchange for curtailment of political liberties. Despite the Stalinist terror and bureaucratic malfunction, ‘actually existing socialism’ was able to provide something for the working-class that capitalism couldn’t. Nostalgia for the Eastern Bloc isn’t simply nationalism but also regret over a loss of tangible material benefits.

With the above taken into consideration, it should be clear that even if the USSR did not represent an authentic workers’ state, it was nonetheless something worth defending: its collapse was a massive setback for the global working class. Those who followed Shachtman were wrong, and Trotsky was right. It was necessary to defend the USSR and the Socialist States from capitalist restoration and imperialist attack while critiquing their bureaucracies and supporting fights for internal changes.

If this sounds like an example of contradictory “doublethink”, let us compare the USSR to a mobbed-up trade union. We always defend unions from busting by the capitalists, regardless of how corrupt their own regime is. Yet we do not support actions by unions that attack the rest of the working class, such as hate strikes, regardless of the fact they are performed by defensive organizations of the workers that they are better off for having. An equivalent in the case of the USSR would be the repression of Prague Spring, the deportation of ethnic minorities, or the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. We must condemn such acts, just as we would condemn hate strikes without joining the chorus of anti-union propaganda. Furthermore, we should support attempts by workers to reform their union, even to replace it with a wholly different union that fits their needs; not only kicking out the most corrupt bureaucrats but structurally changing it.

Of course, the USSR is now gone, so this is no longer a live issue. Leftist groups today do not have to determine the correct way to relate to the USSR as an existing entity. However, we do have to comprehend our past, not only for ourselves but for the public. My suggestion is that Trotsky’s analysis of the USSR gives us a model of how we should comprehend our past, in particular, the legacy of ‘actually existing socialism’. We must recognize that when we carry the burden of our past, we also carry a legacy of struggle for a better world, a struggle that in many cases actually has helped create a better world. If this wasn’t the case, then our faith in communism truly would be an irrational superstition, something we follow against all living evidence. Yes, in the end, the USSR failed, collapsing under its own contradictions. But this need not entail we give up. As Badiou said when challenged on the shortcomings of historical communism,

After millennia of administration centred on private property, we had an experience of collectivisation that lasted for seventy years! How can anyone be surprised that this very brief experience, which was conducted for the first time in history in Russia and China, did not immediately find its stable form, and temporarily failed? This was an assault against a millennia-long taboo; everything had to be invented from scratch without any pre-existing model to go on.

The challenge faced by communists in forging a new society is unique in history: humanity must take history into its own hands, rather than leave it to the blind chance of necessity. To expect full success with every attempt would be foolish. Also foolish would be to join the chorus of the bourgeoisie in condemning every attempt at such a project. To even mimic the tone of these critics is not acceptable. Regardless of how much we are dedicated to the communist ideal in our hearts, joining this chorus only fuels our own doubt and prepares our eventual surrender. Following Trotsky’s example, we must be critical of and see the need for radical changes within our projects, but always while defending the validity of these projects against those who would stomp them out.