Contrary to certain advocates of “Acid Communism”, P.H. Higgins argues that a turn towards counter-culture, consciousness-raising, and psychedelic drugs are not a means to building a better left.

“Political thinking that starts from the concept of the establishment is likely to lead nowhere. For, because it leaves the true centres of power unnoticed and unexamined, it can offer no general picture of the possibilities of our society, of the changes that are necessary, of the way in which the substance of human life could be transformed and enriched through political action.”

– Alasdair MacIntyre, “The Straw Man of the Age”

“Capitalist Realism” — the term, most notably used by Mark Fisher in his 2009 book of the same name, has become the buzzword of the post-Occupy left; it is the catchy diagnosis for a world without hope, and the obstacle any leftist movement must overcome. After Fisher took his own life in 2017, capitalist realism seemed to have become more all-encompassing than ever: Trump was president of the United States, Brexit was swallowing up British politics, climate crisis was going unaddressed, and now it appeared the prophet of a new revolutionary interest had been consumed by despair. However, a glimmer of hope seemed to appear, one last gift from Fisher, in the form of an unfinished introduction to a book titled Acid Communism. In this short text lay Fisher’s very own attempt to overcome the very impediment he had previously described. In September of 2017, Jeremy Gilbert elaborated on his encounters with Fisher and his own role in forming the foundation of Acid Communism, describing it as an attempt to formulate “a radically different conception of freedom to the one which we have inherited from the bourgeois liberal tradition… which understands freedom and agency as things which can only be exercised relationally, in the spaces between bodies, as modes of interaction. It would be the creation, constitution and cultivation of collective creativity.”1 Since the publication of Fisher’s unfinished manuscript in the K-Punk collection, the notion of Acid Communism has continued to garner interest. In their latest issue, Commune magazine has published two ecstatic pieces on the possibilities of Acid Communism by Sarah Jaffe and Emma Stamm. While Jaffe’s piece mostly operates as a tribute and retrospective on Fisher, Stamm’s article proclaims Acid Communism to be a new foundation for a leftist utopian vision based on “the politicization of tripping and trippy art.” Though Stamm’s piece proclaims the necessity of social consciousness, structural changes, and opposition to capitalism, it simultaneously reveals the failure of trendy leftist theorizing to conceive of concrete demands or actively study the societal relations of contemporary global capitalism.2 Using the articles of Gilbert and Stamm as models for Acid Communism, we will identify three major areas where the popular usage of Fisher’s concept fails to make clear its usefulness to leftist politics today:

-

- An excessive focus on drug-use, mysticism, and disorientation as a break from ideology rather than social engagement through discussion of political ends.

- A broad claim that Acid Communism upholds a leftist heritage, without partaking in a real examination of the history, tactics, and failures of that heritage; the latter critique forming a more significant and constructive part of a communist social consciousness.

- Following from the first and second points: a stance of popular autonomism which lends itself towards liberal reformism and lacks the working-class militant interest of previous traditions it claims to be a part of. A kind of “festival-ism.”

SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND BRAIN CHEMISTRY

Despite the provocative title, Fisher’s fragmented piece mentions very little about psychedelic drug use (something that Jeremy Gilbert seems very much aware of).3 In his description of acid communism, Fisher writes, “The concept of acid communism is a provocation and a promise. It is a joke of sorts, but one with a very serious purpose. It points to something that, at one point, seemed inevitable, but which now appears impossible: the convergence of class consciousness, socialist-feminist consciousness-raising, and psychedelic consciousness, the fusion of new social movements with a communist project, an unprecedented aestheticization of everyday life.”4 Perhaps the vague notion of “psychedelic consciousness” could be seen as a call for this drug-haze-as-revolution, though Fisher’s descriptions of “psychedelic consciousness” seem more tied to the expressions in music, popular social movements, and a contested space of what Raymond Williams called the “means of communication as means of production.” Stamm and Gilbert, however, both emphasize the role of drug-induced experiences specifically, with Stamm even writing about their experiences at a bourgeois function for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. The focus on drugs as a means of escaping the effects of depression and anxiety specifically may have some resonance with Fisher’s concerns — his writings on depression and its effects are some of the most poignant pieces in his collected writings. However, one might also remember how skeptical Fisher was of medication as a method of treating the cause (rather than the symptoms) of depression without simultaneously changing social relations and the economic conditions that limited individual flourishing and healing.

If we are fighting to eliminate drug laws, perhaps we should consider the way that such laws often attack the working class and people of color while propagating a system of prison labor and global police measures (not to mention the contemporary immigrant crisis). In 2017 alone there were 1,632,921 drug-related arrests in the United States, with well over half of the arrests being for possession and nearly 600,000 arrests for marijuana possession alone.5 While there has been research showing how drugs like marijuana and psychedelics can potentially alleviate mental and social illnesses, taking clinical trials and then immediately projecting them into a method of politicization is dangerous. If Fisher’s concern for mental health was primarily about a lack of social opportunities and the individualization of social failure, then we should also be looking at less glamorous methods of assisting both cognitive health and social being. This means looking at the restrictions of the legal system, the techniques management utilizes to maintain workplace domination, the structure of the working day, and the growth of precarious and time-consuming gig economies through platforms like Uber. If we are concerned with systemic attacks on social well-being, we should begin with these social relations rather than seeking to provoke individual consciousness with psychedelics, yoga, or rituals.

Gilbert has stated that he’s “not saying everyone should take psychedelic drugs (which are illegal in most countries), or take up yoga, or anything else in particular.” Fair enough, but the only account of revolutionary consciousness given by Gilbert is a sudden refusal of “neoliberal and bourgeois values generally.”6 Even if we are assured that this new refusal will occur through social and communal action, the focus on consciousness as a kind of revelation will always turn back to the individual. To focus on consciousness in this way, even in the name of de-individualizing neoliberal identities, is to take the role of an “ideologue” like Feuerbach or Stirner rather than that of a political revolutionary.

HERITAGE AND HISTORY OF THE NEW LEFT

Stamm writes:

“The Acid Communist movement has helped me view my politics as part of a historical lineage, not a misappropriation of serious Leftism…Gilbert and Fisher both explored the viability of incorporating old-school ‘consciousness-raising’ events in a psychedelic framework. First developed by socialist feminists in the 1970s, consciousness-raising encourages participants to share stories about struggles normally conceived as private and shameful. The idea is that when people tune in to others’ narratives of hardship – which may include accounts of mental illness, social isolation and poverty – such problems revealed as not an exception, but the norm.”

These remarks about the insights of consciousness-raising, intended to connect Acid Communism to the history of real socialist activity, reveal a failure to interrogate that history. The principles of “consciousness-raising” that Acid Communism takes inspiration from are connected to Maoist practices of “speaking bitterness” whereby peasants could be radicalized into attacking their landlords and seizing the grounds which they worked. As Maoism became viewed as a newer, more radical alternative to the official line of Comintern politics in the ’60s, the principles of “speaking bitterness” were adapted into the softer form of consciousness-raising. But what could conscious raising accomplish in the Western urban context? Whether or not a peasant revolution could maintain socialism through a prolonged period of industrialization, there is no doubt that the immediate action of peasants in a developing nation in the midst of civil war is more likely to succeed than cells of oppressed groups in urbanized countries like the United States, Britain, France, or indeed the vast majority of the contemporary world. Mike Macnair of the Communist Party of Great Britain has commented before on the failures of consciousness-raising and its fracturing of Leftist discourse and organization: “While consciousness-raising for workers may often be a waste of time, for women, blacks and gays and lesbians it is a different story. They are hardly in a position to overthrow the exploiter, and their oppression is more diffuse. There is more atomisation. Consciousness-raising may produce radicalisation — but not the ability to move from here to immediately decisive action. The result is as often as not forms of demoralisation.”7 Macnair’s criticisms are not the same as Fisher’s invocation of the infamous “vampire castle”; the issue here is not twitter infighting and virtue signaling, but an actual question of organization. Macnair’s criticism of consciousness-raising is that these methods of trying to expand the discussion of oppression on the left (itself a worthy goal) were implemented without considering plans for decisive action, producing atomization and organizational splintering that could hinder effective strategies and discussions. The left doesn’t have to be composed of friends who agree on everything (anyone who takes more than a glance at the history of the First, Second, or Third International should be well aware of this), but if we do not create methods within our own movement to deal with our disagreements, debate strategy, and come to standards for membership and political action, we will not have a movement at all.

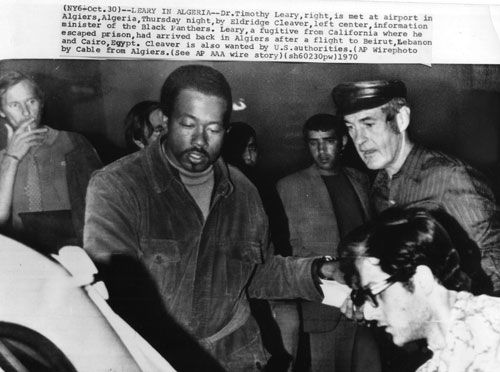

Stamm continues: “Across the US, the reform of drug policy is a popular cause among libertarians and certain factions of the alt-right…When I pressed Jeremy Gilbert on this, he responded that contemporary hippies who embrace libertarianism fail to grasp the political history of their subculture. The New Agers of the mid-20th century, he claimed, were never in favor of capitalist principles.” This answer appears rather historically inaccurate. The contemporary right-libertarian claims to counterculture have historical ties that cannot be construed as merely a misunderstanding or late appropriation. One need only think of famous libertarian Robert A. Heinlein’s simultaneous admiration for drug use and free love in Stranger in a Strange Land and his positive portrayal of militarization and nationalist bravura in Starship Troopers. And what of Tom Wolfe, author of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, who supported George W. Bush? Paleoconservative Paul Gottfried was a student of Herbert Marcuse and has claimed to uphold the lineage of critical methodology from his former professor. 8 There is a dangerous notion here that conservative and reactionary politics is simply passive. As though there were a simple dichotomy between progress on the one hand, and resistance to progress on the other. There are two kinds of progress advancing at the same time – one is the left’s strategy, the other the right. Both political wings produce new operations, goals, and projects in response to each other. The right-wing libertarianism that’s become popular in America is not simply sitting idly by, tricking those who haven’t learned their history. It is a political project that has its own history which connects to ’60s counterculture and has developed strategies through that history. We on the left cannot simply claim to take back all the history of the ’60s as though it has been merely distorted or foiled.

Gilbert insists “I’m not romanticizing the counterculture of the 1960s — but I think its ‘problems’ and ‘failures’ have become so well known and so well-documented that it has become easy to forget both that it had some significant positive effects, and that its failures were not just intrinsic to it, but a result of its political defeat by the New Right and its allies.”9 But we aren’t given an explanation of what the strategies or conditions were that allowed the New Right to overtake the New Left, nor are we given much concrete analysis of what the actual activities of the New Left were besides consciousness-raising, rallies, and the existence of some kind of vague utopian imagination. It is not objectionable to find positive examples of concrete action in the leftist movements of the ’60s, but doing so requires greater historical conviction. The notion that one can simply invert the “drop out” culture of the ’60s into “rise up” seems a gross misunderstanding of the contexts that brought Communists like Marcuse to the New Left in the first place. We cannot forget that much of the western consciousness-raising was done in a situation where the USSR, China, and Cuba had revolutionized while the already industrial and proletarianized west had failed to do so. The interest in consciousness raised by Lukacs, Gramsci, and the Frankfurt School occurred at a moment where authoritarian reaction was already absorbing liberal governments and crushing left-wing opposition. The later interest in consciousness with the New Left was brought about while unions, civil rights activism, and anti-war protests were already in motion. And, again, actual socialist countries (regardless of their usefulness as a contemporary model for socialism) existed and were fighting capitalism and supplying material support to movements around the world. It is hard to say that our contemporary position is much like either of these periods. Yes, there appears to be a new (and often violent) resurgence of reaction. There also seems to be a growth of interest in socialism and a return to discussion about Marxism. This is not necessarily unusual: reaction always grows in response to the appearance of potential for left movements. Persuading people to join in a political position is obviously part of politics, but what is our politics specifically? What are our positions? What is our movement, our organization? An interest in real utopianism and new futures relies just as much on these questions as it does on consciousness as-such.

FESTIVALISM

“While Adorno upheld creativity as a space of revolutionary otherness,” writes Stann, “Fisher said, he did not provide any tangible visions for the politics that art might inform.“ Ironically, it seems the same could be said of this new wave of appropriating the concept of Acid Communism. To continue quoting Stann:

Radical politics, [Gilbert] said, are always utopian, and utopian intentions are wasted without a manifest blueprint for change. Psychedelic art, with its message of love and transcendence, delivers. ‘It’s not going to be for everybody,’ he clarified. But he indicated that its recognizable styles — whirling geometric patterns, fractals, and musical intricacy — offer an ‘aesthetics of complexity’ which contrast with the dull reductiveness of capitalist realism. ‘Not many people allow themselves the full extent of their complexity,’ he said, quoting composer Arthur Russell. With its multidimensional intricacies, both the art and the drugs might throw the banality of contemporary popular media into high relief.

But what vision of Utopia is here? If one were to look at another, relatively overlooked Frankfurt School figure, Ernst Bloch, one would see a much deeper and serious engagement with the notion of utopia whereby the concept of utopia throughout history is the imaginative capacity of people to think of a world without class divisions. Bloch’s project of utopian imagination, like Adorno’s interest in consciousness, was grounded in the rise of fascism, and later his professorship in East Germany. While Bloch appreciated the interest in the myths and stories of the past, he always insisted on the necessity of grounding action in the possibilities and structures of the present: “The friend of true enlightenment will hardly withhold his delight at and gratitude for such prefigurations and their instruction. But the activity of the intellect involving the processes of amending, augmenting, and illuminating the world from the basis of the world always starts out from a scientifically achieved awareness that retains a certain given context.”10 Acid Communism generally claims to be upholding the history of the left, the principle of utopia, radical action, communism, but the actual visions of the future are put aside in favor of the activities which are integrated into the aesthetics of “whirling geometric fractals.” Jeremy Gilbert makes the astute observation that “we inhabit a culture whose institutions, laws, economies and social practices have for centuries been organised around the opposite idea, attributing individual responsibility to every action, treating private property as the foundation on which society is built, teaching us that private emotion is the seat of authentic experience. Under these circumstances, learning to function in such a way that the knowledge that nobody is really an in-dividual (i.e. indivisible, independent of social relations) becomes more than just abstract theory, is immensely challenging” only to follow up with a turn to ‘the whole countercultural panoply of raves, drugs, yoga, chi-kung, Zen etc.” and some “set of practices and ideas which are at one and the same time mystical and materialist — a materialist mysticism which acknowledges the complex potentialities of human embodied existence, without tying that recognition to any set of supernatural or theistic beliefs.”11 This is not a utopian vision, but a substitution.

It is true that interest in the festival and its role in social bonding has a significant part in leftist thought. The topic of social kinship and engagement through festivals and gifts is an important topic of inquiry in sociology and anthropology appearing as far back as Marcel Mauss’s The Gift and Franz Baermann Steiner’s Taboo. The French Marxist Henri Lefebvre, inspiration to the Situationists, took the ecstatic descriptions of festival in Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel as an early form of communal, revolutionary activity whose elements could be found in the crevices of contemporary life. Concern for meaning, practice, friendship, and fulfillment in everyday life has been an important part of turning individuals to the left and is particularly important for those who are subject to domination and exclusion in the public sphere due to their identity and/or ability. It is not unreasonable to believe that a new communist movement requires a legitimate concern for and analysis of the practices of everyday life, considering the wide variety of everyday experiences that many communities can have within the same spaces. However, even if a new social life is necessary, and even if a mass left movement would benefit from its own methods of socializing, recreation, and enjoyment, it is one thing to say this should grow out of a unity of worker’s movement and communist political platform, quite another to proclaim this is itself the political action of communism in the present.

While autonomist movements emerging in the United States (the Johnson-Forest tendency), Italy (“operaismo”), and France (Socialisme ou Barbarie) ultimately failed in producing movements capable of seizing and holding power, their interest in uncovering the desires of the workers is something the contemporary left can make use of, but the festivalism of Acid Communism isn’t willing to conceive of itself operating on the shop floor when it would prefer a dance floor. Counterculturalism that originates outside of the interests of the proletariat — who are composed of numerous social and cultural backgrounds — is liable to alienate them and appear farcical or frivolous. A leftist culture originates from the social grounds and desires of the proletariat; it is not viable to simply choose an image that stands in opposition to an image of “the establishment.” We would do well to consider yet another New Left veteran, the ethicist and ex-Trotskyist Alasdair MacIntyre, who wrote of the New Left:

Their thinking is imprisoned by two contradictions which prevent growth in socialist thought beyond a certain point. The first of these concerns the relation between a capitalist economy and the variety of social institutions within such an economy. The second concerns the problem of socialist organization… the New Left wants to stress both the all-pervasive corrupting influence of capitalism and the possibility of transforming institutions within capitalism…the trouble with this demand for building in the ‘here and now’ is its ambiguity. If this is offered as an alternative to building a working-class movement then it is doomed to frustration and failure. If on the other hand it is, as it could be, a way into the class struggle then it is important and full of possibility. For clearly, trying to create forms of community or culture which are opposed to the values of capitalism will at once bring one into social conflict.12

The focus on consciousness as some mystical quality to be played with, combined with the failure to appropriately study the history of the New Left and instead fetishize its appearances and figures, have returned us to this organizational problem. If there is potential in Acid Communism, it must explicitly see itself as a part of class struggle, not merely an opposition to social alienation and privatization. The revolutionary desires of the working class are already developed through the limitations of capitalism. Surely the working class already knows that it hates long hours, living by wages, the commodification of everyday values, and the precarity of the economy and job market. The point isn’t to make them suddenly realize they’re unhappy and want something different; the point is to give the working-class opportunities to express and act on the desires and needs that they already have through political and social revolution. Gilbert claims “the very notion of ‘class politics’ is simply oxymoronic,”13 and in doing so he does nothing to ground Acid Communism in the demystification of material relations. Instead, he skirts the issue by treating class struggle as something self-evident, something that just happens when enough individual interests simply align. If Acid Communism isn’t ready to ready itself as a proponent of real class conflict as opposed to merely recreation, then it will not be a revolutionary asset.

A RETURN TO STRATEGY

The issue here is strategy, not the proposition that Acid Communism is a strategy or should be one, but contextualizing the ideas presented by Acid Communism as a potential part of a strategy:

Is Acid Communism a rhetorical position? A center from which to produce aesthetics, discussions, and appeals in order to bolster a movement? If so, we need to start thinking in terms of a movement, which means Acid Communism must develop political positions and not simply demand an “end to capitalism” without considering what comes afterwards. How, exactly, the left should present itself given the long shadow of its history remains an open question. Anyone who has dealt with persons from (or who trace their descent to) the Ukraine, Cuba, Cambodia, or Peru (among many other countries with complicated, and sometimes terrible, relationships with state communist parties and vanguards) must acknowledge that historical defensiveness must be dealt with pragmatically and with respect to the failures of our own historical movements. We cannot always assume that those who are afraid of the associations of communism are acting in bad faith or are unreasonably exaggerating.

Is Acid Communism a research project in the strategies and activities of the New Left and late Western Marxisms of the ’60s? If so, it should not merely represent itself as a part of a “heritage” but take an active stance in rigorously debating, researching, and criticizing the movements of the ’60s even as it affirms their vision and potential. Politics is not simply invoking a culture and past optimism that is passed down through music, fashion, and a vague notion of altered consciousness in cognitive experiments.

Is Acid Communism about new ways to engage with social consciousness? If so, what are we producing consciousness of? Again, realizing capitalism is simply bad or harmful isn’t enough. Encouraging a real reflection on desire as a need, and desire as a part of a social sphere, is a step forward — but this alone does not guarantee a revolutionary project or even a revolutionary worldview. The failures of the sudden insurrectionary moments of the ’60s should be our starting point here: the sudden, mass realization of desires and utopian possibilities is not enough without an attempt to organize and plan. Social bases are important, they are not the end. We need to have a base of people who can recognize what they want from and for the future, we also need a position that can mediate those desires and think about the structure of a world that can listen to and attend to those desires through social action that is not currently possible.

It may be true that the concepts embedded in Acid Communism “could be a component of a dynamic, experimental Leftism that is as interested in creativity as it is in critique,” but whatever insights Fisher’s final manuscript might have contained, it will be of little use if it is overshadowed by idealized approaches to politics. If Acid Communism is going to be a component of leftist politics it must also be willing to identify its role in a greater strategy with end goals and demands, not merely claim to be an exercise in building some kind of vision — a circular project without a social movement already interested in mobilizing around such visions. Social community, mental wellbeing, and understanding of the real social desires and needs of individuals (desires and needs that are informed by race, gender, sexuality, and numerous other social identities as well as class) are all important issues for a left movement to address, but the lack of any real discussion of the social, material causes of these problems will always lead back to capitalist realism. A utopian vision of the future won’t simply come from some existential shift in individual consciousness. Global networks and communications, dark factories, universal healthcare, urban restructuring, public transportation, global redistribution of resources, a reduced workweek — these are all better foundations for a utopian future than so many festivals and trips will ever be. This utopian possibility will only matter if we conceive of these possibilities as a battleground for class struggle to be fought be a real, organized movement. If Acid Communism cannot conceive of itself within these terms, then it is sure to be a bad trip.